This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

At Palo Alto Networks, Unit 42 analyzes threats across the spectrum – from nation state all the way down to Florida state. In this blog, I’ll be covering two aspects of multi-year affiliate marketing spam campaigns designed to deceive individuals, scam, and profit off of people’s desire to change their lives.

First, I’ll provide an overview of a spam campaign sent to some customers that led me down this more than two year rabbit hole, and then dig into the inner workings. This blog covers a number of topics: data collection, analysis, and enumeration of infrastructure. These efforts allowed us to map out thousands of compromised servers and abused domains and hundreds of compromised accounts, resulting in a collaborative effort with GoDaddy to take down over 15,000 subdomains being used across these campaigns.

Introduction

On a scale of 1 to 10 for the “Worst Types of Spam” you can receive, approaching that perfect 10 score is spam related to “snake oil” products that are so patently fake that you struggle to understand why they would even bother trying to sell it. You know the ones I’m talking about. The late night, 3A.M. insomnia, as-seen-on-TV, “miracle” products that use laughably bad actors to try and sell you laughably bad products…for a limited time only!

At some point the 3A.M. commercials of yesteryear became all-day e-mails, social media posts, and other forms of invasive advertising that have weaseled their way into our daily lives. So much so that sometimes they just begin to blend into the minutiae of things bombarding us constantly and become part of our expected usage experience; we begin to just glaze over them without giving them a second thought. That’s exactly what was happening to me for a particular campaign of spam that I was seeing every now and then but didn’t give much thought to. It went on for over two years and I began noticing slight variations every month until something clicked and what once was background noise now was something of interest.

At first it’s easy to look past them – “Ah! Just another weight loss pill” or “Yes! I’m sure this totally legit Canadian pharmacy has you covered for pain medications.” However, as I began to notice a pattern in the visual structure across some of these spam websites it piqued my interest. Over two years I had watched some of these sites and could identify a template being used that slowly morphed over time, selling different products, and always using different URLs to mask their intentions, but visually appearing quite similar.

Maybe you’ll recognize one of them if you’ve ever been adventurous enough to see where a random link in an e-mail would take you.

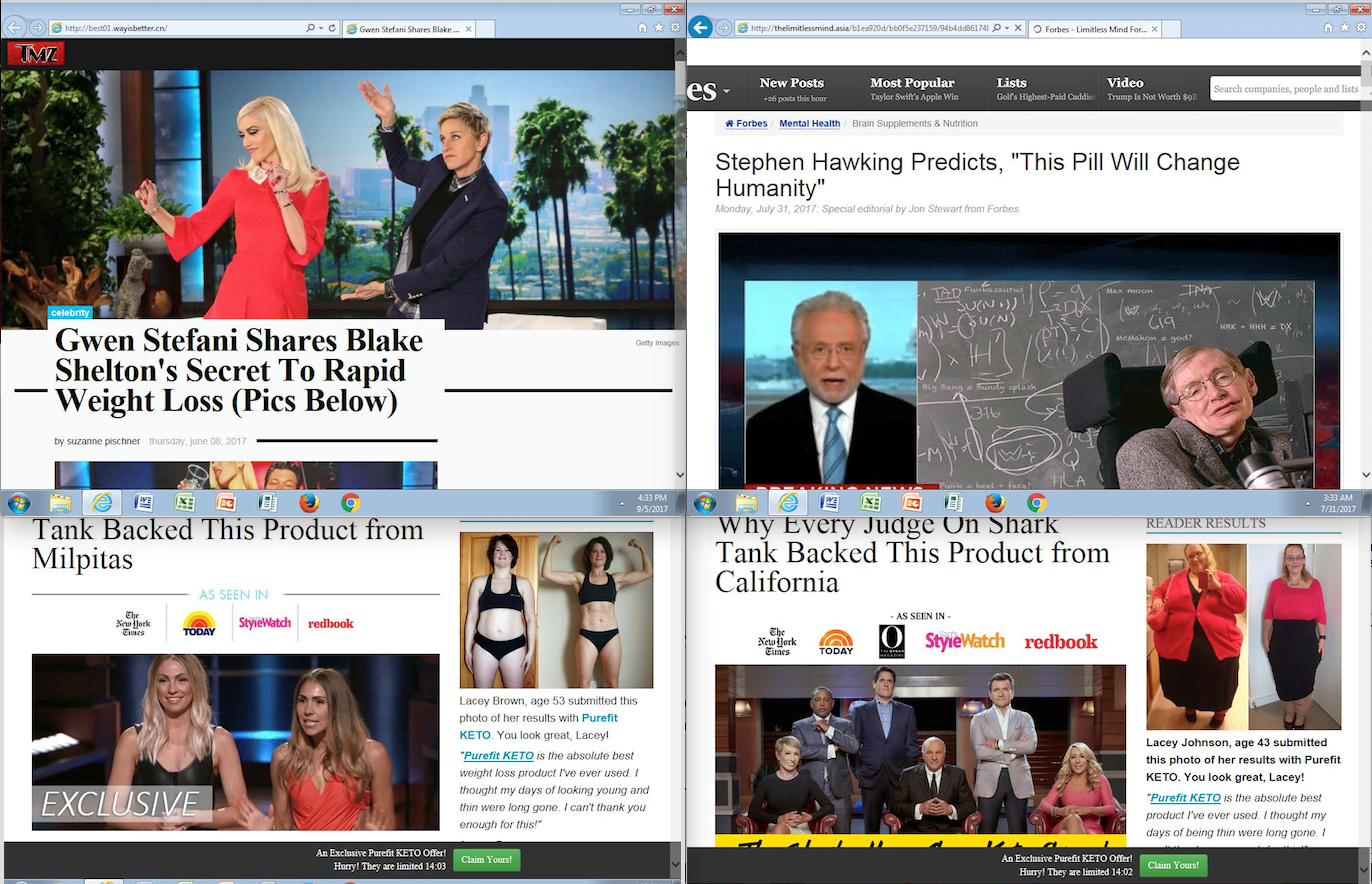

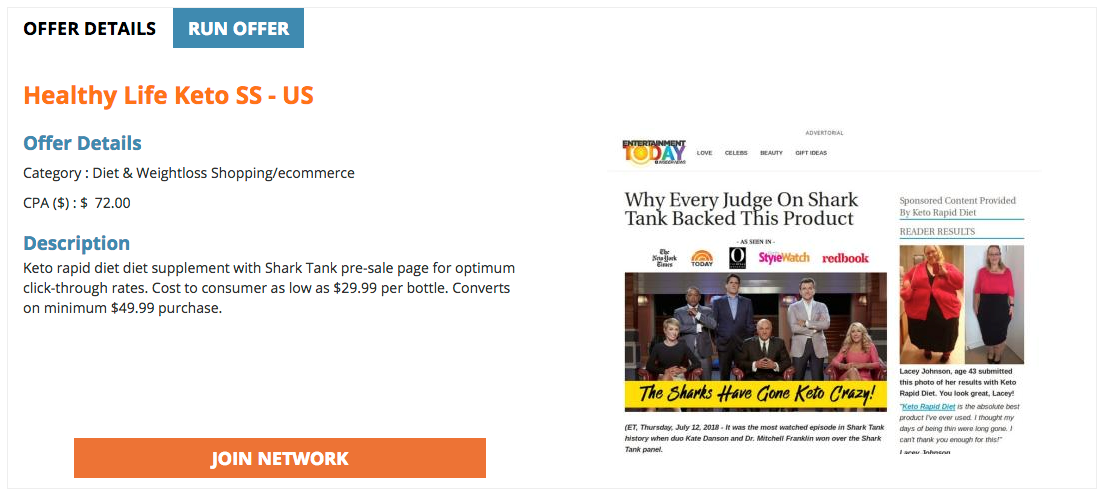

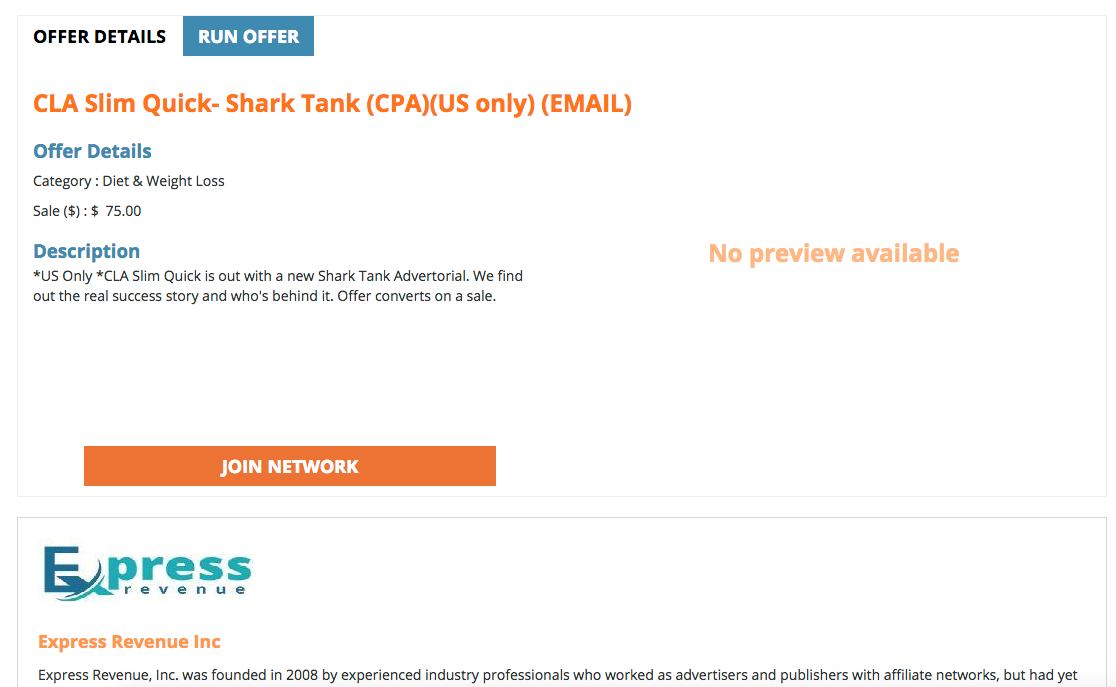

Figure 1. Deceptive scam pages

At times, it was clear, based on domains like “keywestinns[.]com”, that there was something a little more nefarious going on. When I started to investigate, I was seeing hundreds of different domains, with lots of them showing signs of compromise, and quite clearly NOT intended for the spam being used on their infrastructure.

When the act of sending unsolicited offers crosses the line from annoyance to dabbling in illegal acts, then the everyday spam becomes a lot more interesting.

And with that dear readers, it’s time to gather around the camp fire as we go down some rabbit holes on a journey of exploration into the magical mystical world of affiliate marketing spam.

Initial Patterns of Shadiness

To begin, I feel it’s best to highlight some of the spam that initially piqued my interest.

Starting in early 2017, I began making a mental note of these sites purporting celebrity endorsements for weight loss and “brain enhancement” pills. In our process of analysis, we’re presented with an array of screenshots from the virtual systems that crawl these websites; this is why after seeing these images time and time again they eventually became ingrained in my mind and I could start to recognize templates being used and their slight variations over time.

Thus, I present to you some of the first campaigns that I observed throughout 2017. Note the structural similarities as I go through them.

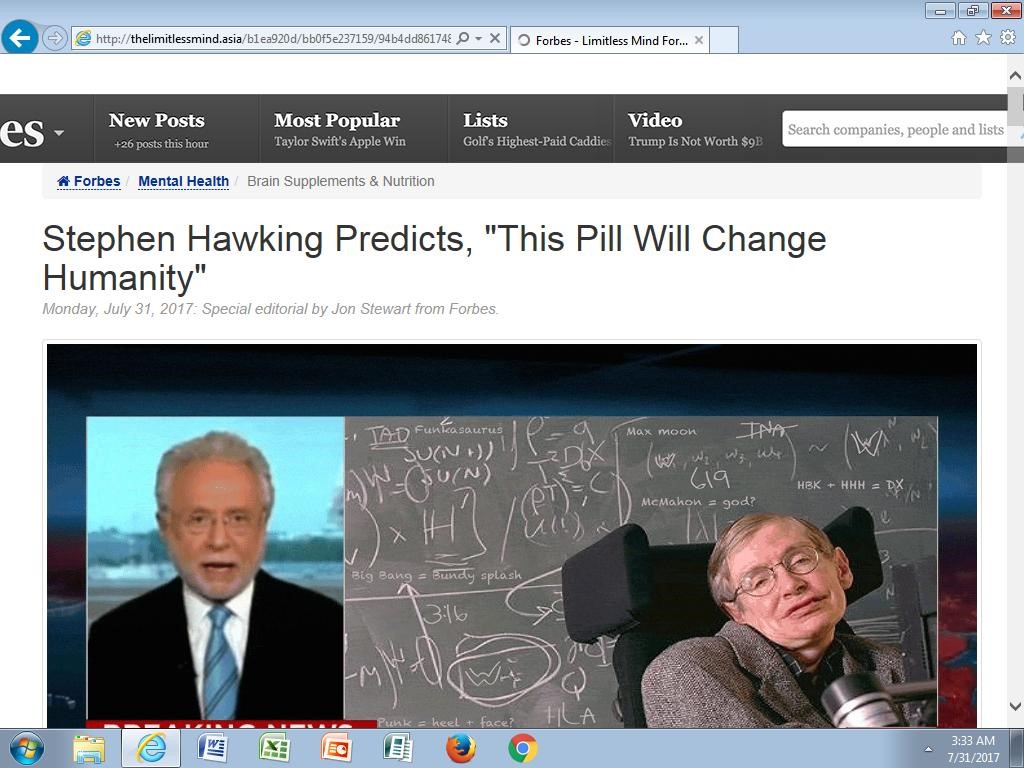

Style A) “Stephen Hawking Predicts, ‘This Pill Will Change Humanity’”

Figure 2. Stephen Hawking variant

A lofty claim for sure and who wouldn’t believe what Stephen Hawking says to Wolf Blitzer as reported on Forbes? While this campaign phased out, there was another running in parallel with the same tactics but a different product, switching from “brain supplements” to “weight loss.” It keeps the celebrity endorsement theme and continues masquerading as a legitimate website.

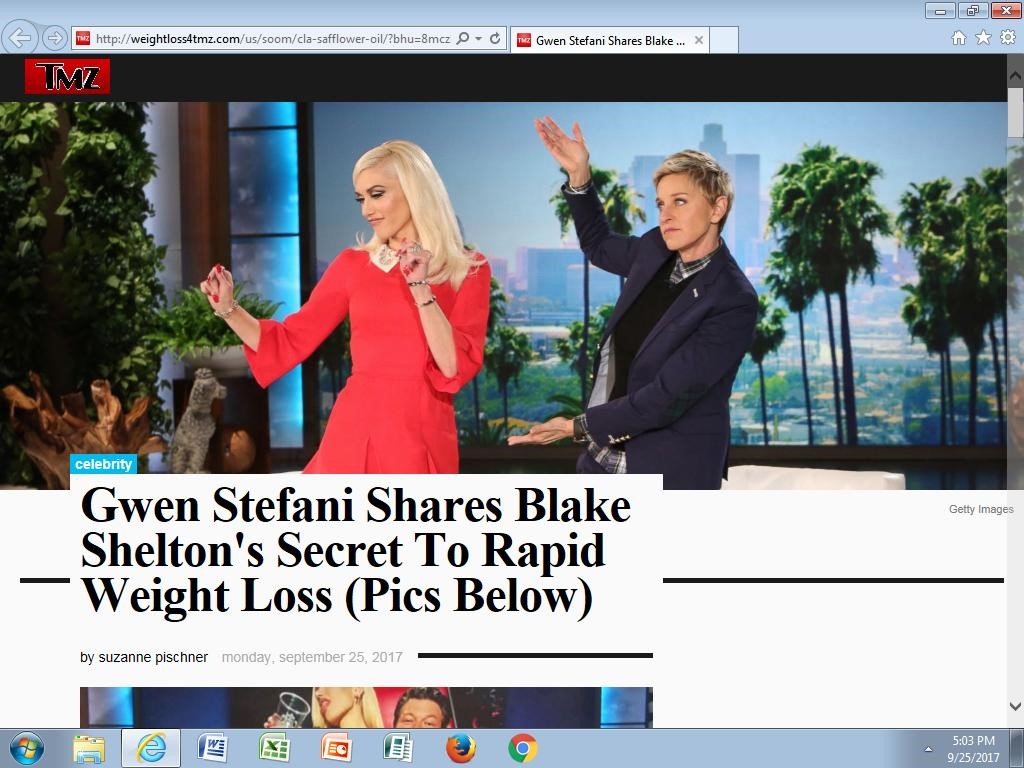

Style B) “Gwen Stefani Shares Blake Shelton’s Secret To Rapid Weight Loss”

Figure 3. Gwen Stefani variant

I’ll touch on the domains in a minute but note that this domain is crafted specifically for this fake endorsement. It masquerades as the legitimate “TMZ” website with a domain using the brand in the name - “weightloss4tmz[.]com”.

After these two died off, two new campaigns began popping-up around early-2018 and are still active as of today.

Style C) “Why Every Judge On Shark Tank Backed This Product from” – Lacey Brown

Figure 4. Shark Tank variant 1

Style D) “Why Every Judge On Shark Tank Backed This Product from” – Lacey Johnson

Figure 5. Shark Tank variant 2

When you see them next to each other, the templates become more apparent in the stylization of their structured layouts.

Keep in mind that the URLs on display in the above screenshots are not what the initial phishing URL looks like, but they are where you eventually end up after, sometimes, 3-4 redirects away from their point of origin. When I finally decided to do some research on these campaigns and figure out what was going on, this detail made initial identification a bit trickier.

Below is a table showing the original URLs and the domains where they ended up in the four images above.

| Style | Primary Redirector | Landing Page |

| Hawking | test.303[.]lt/captchaimage.php?island=asevp275rbaahnz92 | thelimitlessmind[.]asia |

| Stefani | www.printercustomersupportonline[.]com/500error.php?method=283hyxr6r8hew | weightloss4tmz[.]com |

| SharkTankV1 | argentina.urbansquares[.]com/efvpmubb.php?er608q1=h6cmt | health4burnfats[.]world |

| SharkTankV2 | cinematto[.]ch/wp-content/plugins/linklove/profiles/e080403.php?engine=nyq1an0gq1kt02v | fastdiet4lines[.]world |

Table 1. Redirection URL per variant

As I started to manually sift through the URLs I processed, looking for past samples to collect from each campaign, I noticed an interesting pattern that spanned across the URLs going back years. Specifically, the initial redirection page was commonly using a PHP file with a single parameter that was typically a simple English word followed by a mix of alphanumeric characters. It was enough to create a regular expression and match additional sites but I kept finding outliers where it wasn’t always consistent, such as in the above SharkTankV1 sample, and I needed to find a way to collect more holistic data.

I needed a way of identifying all of the campaign variants we’d seen over the past few years without relying on the initial URL from the phishing email. A tricky problem to be sure. In addition, I still wanted to identify the “bit[.]ly” and “goo[.]gl” type shortening services, the redirectors, and in some cases the landing pages to see if any patterns appeared - basically, whatever a potential victim saw. Thus, the only consistent piece of the puzzle I had at that point were the images from our virtual systems used for analysis, so I decided to start from there and work my way backwards.

Spam Cartography

I reviewed a number of methodologies on image comparison and settled on Mean Squared Error (MSE). This technique essentially generates a measurement score based on the average of the squares of errors, or in this context the difference between pixel intensity of the two compared images. As every screenshot was of the same size and general layout within the virtual machine, this relatively simple method proved quite accurate at scale.

Using this fabulous blog I cobbled together a Python script that iterated over 42,000 images from our virtual systems where URLs were sent for manual analysis. I did this for each campaign “style” and reported back matches that I then could use to walk back to the submitted URL, after which I manually scraped out the landing page URLs.

Below are some statistics on how many unique sites and domains were collected following this methodology.

| Style | Total Submissions | Unique Source URL | Unique Landing Domain |

| Hawking | 256 | 81 | 54 |

| Stefani | 93 | 38 | 21 |

| SharkTankV1 | 443 | 217 | 71 |

| SharkTankV2 | 108 | 39 | 19 |

Table 2. Campaign variant statistics

One thing that was immediately surprising to me was the sheer number of unique, purchased landing page domains used for these campaigns.

With a sizable corpus of samples from each campaign, I began looking at them deeper to understand how the flow of events occurred and to try and answer the question: how does one actually land on any of these pages?

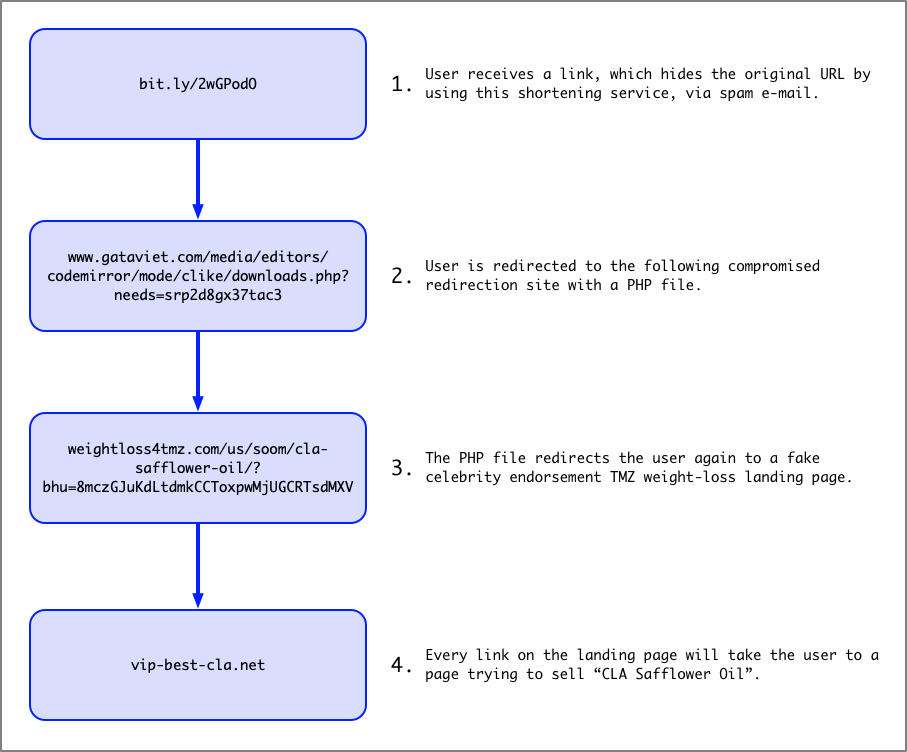

After speaking with some of our customers, hunting for various URLs, and reviewing quite a few other research blogs, I was able to put together a pretty clear chain of events.

- User clicks a link from spam e-mails, random/hijacked Skype messages, Facebook ads, and Twitter posts.

- User ends up on a redirection site, which were usually legitimate sites compromised in some way, which may involve a few hops.

- User ends up on a fake celebrity endorsement landing page.

- User ends up ultimately on a sales page for the product being sold.

Figure 6 shows an in-the-wild example that maps out each step:

Figure 6. Chain of events from original source to destination

Starting with the compromised site portion of the chain seemed like an ideal choice to focus on but I could tell from the samples I’d already collected that not all of them used the PHP file for redirection. In fact, as I started to look at each of the campaigns and chains in more detail, I identified multiple styles in how the redirection was occurring at this phase.

Using RiskIQ’s PassiveTotal service to pivot on sites that redirected to or from the compromised sites, I was able to map out 689 landing pages that mapped back to a whopping 21,611 potentially compromised websites. I thought that was quite an extensive network for trying to push fake products so I continued digging.

While looking at some of the metadata for the compromised sites, I stumbled across a tag in PassiveTotal created by one of their security researchers, Jordan Herman, called “CaesarV”. The description of their tag lined up perfectly with some of the activity I was seeing.

The CaesarV injection is using .php files on compromised site to drive traffic to fraudulent and/or scam pages including fake tech support and fake sites purporting to be news sites reporting on the incredible effects of weightloss and intelligence pills. It is unclear whether it is also sending traffic malware at this time. The injection uses a Caesar cipher to obfuscate the method of redirection and the address to which traffic is being sent. This campaign appears to be long running, at least since the beginning of 2017 and possibly much longer.

Jordan sent me a link to a September 2017 blog PassiveTotal released which featured the Stephen Hawking campaign shown in Figure 2). It detailed how the spammers were able to get access to one of the compromised servers and analyzed the PHP file handling the redirection.

Of note was the use of a Caesar cipher to unmask the hardcoded landing pages to which potential victims would be redirected.

I’ll briefly illustrate this style before covering the additional ones that I saw across my sample set.

Traffic Redirection Styling

CaesarV

For the CaesarV style, at the bottom of the redirect page there is JavaScript block that contains something like the below.

pursuea=24; pursueb=[128,140,140,136,82,71,71,136,138,135,124,141,123,140,76,124,129,125,140,70,143,135,138,132,124,71,87,121,85,76,73,79,79,78,80,62,123,85,123,136,123,124,129,125,140,62,139,85,75,77,79,78,77]; pursuec=""; for(pursued=0;pursued<pursueb.length;pursued++) { pursuec+=String.fromCharCode(pursueb[pursued]-pursuea); } window.top.location.href=pursuec;

It’s just a basic array of integers, shifted in this case by “24”, that represent the ASCII characters which make up the URL.

>>> a = [128,140,140,136,82,71,71,136,138,135,124,141,123,140,76,124,129,125,140,70,143,135,138,132,124,71,87,121,85,76,73,79,79,78,80,62,123,85,123,136,123,124,129,125,140,62,139,85,75,77,79,78,77]

>>> "".join([chr(x - 24) for x in a])

'http://product4diet[.]world/?a=417768&c=cpcdiet&s=35765'

JavaScript Variant 2

Another JavaScript variant that I frequently saw used a simple string ordering obfuscation to hide the URL before it rebuilds it.

var kbgo361 = 'h';

var elqwcafz962 = 't';

var yxkqcakbda622 = 't';

var fwvpixzxqktl166 = 'p';

var a173 = 's';

var jxatwangn716 = ':';

var iqt449 = '/';

var zlovsta404 = '/';

var sp811 = 'on=';

var rdzvxyaxbo26 = 'xoa139';

var qzcdsfakgdfxrd419 = 'ment';

var j56 = '.lo';

var iwzarqkozwkt588 = 'ti';

var mbxctnfabkctpvqro857 = 'docu';

var vnv639 = 't-lines.co';

var fcieo806 = 'm/held.php';

var anmssiwwzfokxyxt304 = '?a=';

var ibtjenthjslooiilw172 = '1kB';

var ax83 = 'J&c=diet&s=10058';

var svxvv466 = '';

var bvengcktogsc110 = 'fastdie';

var xoa139 = 'ca';

var brndzqejxjhbvsro400 = '"';

if (rdzvxyaxbo26 = 'xoa139') {

setTimeout (mbxctnfabkctpvqro857+qzcdsfakgdfxrd419+j56+xoa139+iwzarqkozwkt588+sp811+brndzqejxjhbvsro400+kbgo361+elqwcafz962+yxkqcakbda622+fwvpixzxqktl166+a173+jxatwangn716+iqt449+zlovsta404+svxvv466+bvengcktogsc110+vnv639+fcieo806+anmssiwwzfokxyxt304+ibtjenthjslooiilw172+ax83+brndzqejxjhbvsro400,916);

}

This redirects the browser to a PHP file on a landing page server:

https://fastdiet-lines[.]com/held.php?a=1kBJ&c=diet&s=10058

Then this site uses a 303 “See Other” HTTP request to redirect to the final landing page. It’s worth noting at this point the parameters “a” (Affiliate), “c” (Campaign), and “s” (Sub) that are included in the above request.

https://fastdiet-lines[.]com/us/wykc/keto-all-desktop3?bhu=spctECr16tLfm14ZpdEZun3r45xPcSviq2L12u

3XX Redirect Chain

The last dominant style I’ll cover is a chaining of HTTP 3XX Redirection requests as illustrated in the example below.

Figure 7. 3XX Redirection chain

As an aside, all of the certificates I observed across these campaigns when HTTPS was used were issued by “Let’s Encrypt”, which offers free and automated certificate creation quite commonly abused by malicious actors.

While collecting these URLs, the 3XX style of redirection illuminated another area of clearly illegal activity. Over the past few months, I noticed a large influx in this style of redirect being pushed out and hitting my radar. While speaking with one of our customers to understand where they were receiving the initial URL’s from, they sent me some of the “hundreds” of e-mails they were receiving leading to these campaigns.

Upon closer inspection I determined they all followed a similar structure of one simple English word used as a subdomain to an unrelated second level domain. Below is a sampling to illustrate.

- accept.beerandcupcakes[.]com

- belief.saltwaterfall[.]com

- card.fallingrockfilms[.]com

- decision.welcometomydiabeticlife[.]com

- else.pageinvestmentgroup[.]com

- favor.bigislandroofing[.]com

- glad.justinbieberfannews[.]com

- heart.mkmarketingservices[.]com

- ideal.modularelectronicsystems[.]com

- just.eastcoastrandr[.]com

Out of the over 4,000 sites I further enumerated from PassiveTotal that both follow this naming pattern and had relationships to known landing pages, were 3,000 unique second level domains. I’ll come back to this point later but for now, just know that a majority of them resolved to the IP address “184.168.131[.]24” which is the GoDaddy URL shortening service, similar to “bit.ly” and “goo.gl”, but allows you to point a DNS A Record to the IP and manage where it will forward the user.

Figure 8. GoDaddy URL shortener/redirector

The primary difference here is that instead of compromising a WordPress plugin on an unrelated website, as seen in the previous campaigns, they were now using legitimate registrant accounts in a technique called “Domain Shadowing.” Additionally, at the scale I was seeing, it would seem likely that the person(s) behind it were going about it in an automated fashion, logging into these legitimate domain accounts and using a dictionary of simple English words to create subdomains pointing to their redirector.

The automated aspect of this can be further evidenced below when you look at the update time for the various domains and cluster them on that facet.

- onlinebusinesstrainingacademy[.]org | GoDaddy.com, LLC | 2018-11-12T10:35:19.000-0800

- onlinebusinesstrainingschool[.]org | GoDaddy.com, LLC | 2018-11-12T10:35:18.000-0800

- onlinebusinessu[.]org | GoDaddy.com, LLC | 2018-11-12T10:35:18.000-0800

- onlinejobtrainingacademy[.]com | GoDaddy.com, LLC | 2018-11-12T10:35:18.000-0800

- onlinejobtrainingschool[.]com | GoDaddy.com, LLC | 2018-11-12T10:35:17.000-0800

- onlineworktrainingschool[.]com | GoDaddy.com, LLC | 2018-11-12T10:35:18.000-0800

Each of these domains were created around the same time back in 2016 and visually appear related, even though they all used private registration with GoDaddy. They also all share a last updated WHOIS time within a few seconds of each other and this implies these were updated at the same time, likely because they are all related to the same registrant account.

Furthermore, you’ll find that it’s not a 1:1 mapping of subdomain to domain and quite a few subdomains are abused in this fashion per second level domain.

- advantage.onlinebusinesstrainingacademy[.]org

- principle.onlinebusinesstrainingacademy[.]org

- speak.onlinebusinesstrainingacademy[.]org

- text.onlinebusinesstrainingacademy[.]org

- venue.onlinebusinesstrainingacademy[.]org

- chat.onlinebusinesstrainingschool[.]org

- sale.onlinebusinesstrainingschool[.]org

- server.onlinebusinesstrainingschool[.]org

- store.onlinebusinesstrainingschool[.]org

- title.onlinebusinesstrainingschool[.]org

- value.onlinebusinesstrainingschool[.]org

- browse.onlinebusinessu[.]org

- develop.onlinebusinessu[.]org

- direct.onlinebusinessu[.]org

- esteem.onlinebusinessu[.]org

- guide.onlinebusinessu[.]org

- main.onlinebusinessu[.]org

- voice.onlinebusinessu[.]org

- always.onlinejobtrainingacademy[.]com

- ideal.onlinejobtrainingacademy[.]com

- market.onlinejobtrainingacademy[.]com

- set.onlinejobtrainingacademy[.]com

- smart.onlinejobtrainingacademy[.]com

- then.onlinejobtrainingacademy[.]com

- venue.onlinejobtrainingacademy[.]com

- branch.onlinejobtrainingschool[.]com

- card.onlinejobtrainingschool[.]com

- cheap.onlinejobtrainingschool[.]com

- great.onlinejobtrainingschool[.]com

- note.onlinejobtrainingschool[.]com

- sight.onlinejobtrainingschool[.]com

- stable.onlinejobtrainingschool[.]com

- balance.onlineworktrainingschool[.]com

- chief.onlineworktrainingschool[.]com

- expect.onlineworktrainingschool[.]com

- guide.onlineworktrainingschool[.]com

- kind.onlineworktrainingschool[.]com

- refer.onlineworktrainingschool[.]com

- respect.onlineworktrainingschool[.]com

As you can see, this technique gives an attacker a much larger surface area of URLs to use than just compromising an individual website via WordPress plugins.

Affiliates in Crime

While looking at these URLs in bulk, one set of artifacts that kept standing out was the naming of the parameters. You have things like “click_id”, “subid”, “ad”, “CID”, etc. These all indicate a tracking system which is typical of affiliate advertising.

Affiliate advertising, in this context, is a perversion of traditional advertising that incentivizes individuals to aggressively push traffic towards a product by paying for views, clicks, and other activity. Wikipedia provides a slightly more palatable definition:

Affiliate marketing is a type of performance-based marketing in which a business rewards one or more affiliates for each visitor or customer brought by the affiliate's own marketing efforts.

Technically, there is nothing wrong with affiliate marketing, but when affiliates use less than scrupulous methods for traffic generation, it puts the onus on the marketing company (merchant and/or affiliate network) to filter out the bad apples.

Another important analytical point is that it is relatively simple to separate out individuals to blame for the illegal activity by having a basic understanding of how affiliate marketing works and analyzing the different styling of the redirections. They are paid by merchants to push traffic, however they can, to these deceptive websites. It’s possible, based on the parameters in use on the landing pages, for the merchant handling these services to track back this illegal activity to their affiliates they are paying and put a stop to it. But more often than not, the merchants themselves are providing the affiliates with the fake celebrity endorsement templates and are just as unscrupulous as the affiliates.

The merchants are very aware of who is abusing these systems but are making a profit and as this type of crime is rarely prosecuted, lack significant incentive to police the activity. I observed that victims frequently asked credit card vendors to cancel charges to these merchants and also complained directly to the merchants as well as organizations like the Better Business Bureau

Landing (Pre-Sell/Farticles) Pages

After enumerating out all of the relationships with the compromised servers and hijacked registrant accounts, based on their observed redirection activity in PassiveTotal, I was now left with a large grouping of landing pages to further analyze.

In the affiliate marketing community, these types of fake endorsement sites are called “pre-sells” and “farticles” (yes, farticles…fake articles). The pages intent is clear - get someone to believe the products may actually work if a celebrity endorses it. That’s a tactic as old as advertising itself.

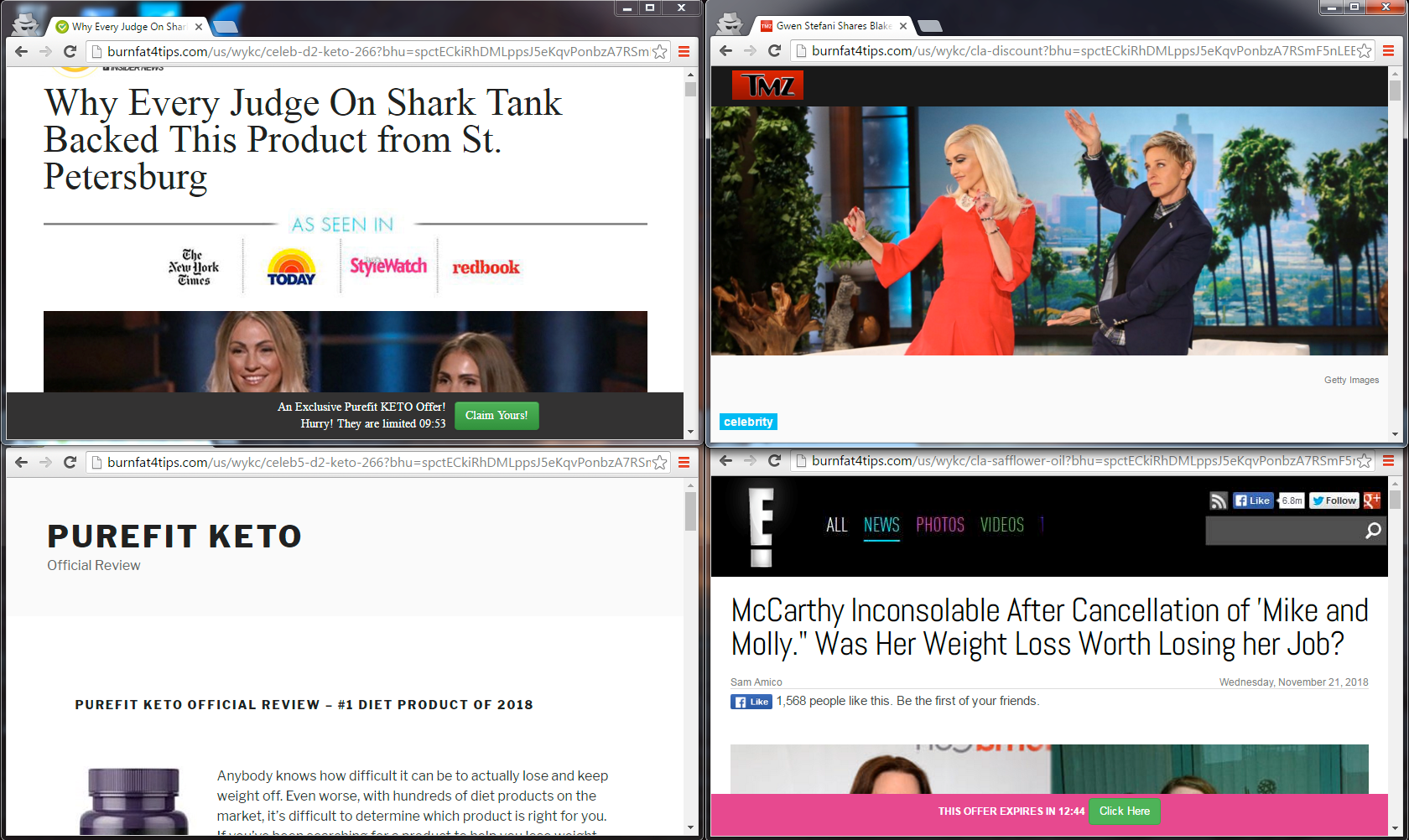

You’ll also find these exact pre-sells being offered to affiliates by the affiliate networks and merchants.

Figure 9. Shark Tank pre-sell

Another interesting thing that I noticed while analyzing these pages is that each of the landing page sites contained other landing pages that I’d seen before, and some which I hadn’t, that were not currently in use. Even when the pages weren’t related to the domain, the templates for these other products still existed on those sites. This, to me, is a clear indication of a bundled package being deployed to the servers and, based on what I saw across multiple affiliate platforms, are typically products provided by the merchants themselves.

Below is the “burnfat4tips[.]com” domain illustrating multiple pre-sell pages at different URL paths.

Figure 10. Multiple campaign templates per site

By enumerating all of the URL paths from the pages submitted by our customers, I was able to identify 26 templates on just this site alone. I’m sure there are even more into which I don’t have visibility.

As mentioned previously, these landing pages do nothing more than attempt to elicit a click from the viewer. Every single link, “contact us” button, Facebook like, Twitter re-tweet, etc all point to the same resource – another PHP script which handles the redirection to the “miracle cure” sales page. Even when some of the pre-sell pages are promoting a different product, such as “CLA Safflower Oil” or “Turmeric”, these all eventually redirect to the “PureFit Keto” sales page for this particular campaign.

Going back a little, between June 12 – 15 2017, the redirect for the sales page in the Stephen Hawking variant changed their PHP file from this format:

togo.php?lnk=7e7525addd988e89&a=aER5clJOVnFSWGVFYjY4bW5DMkEyUmN3a3ZtRUxvUGYyck9FTFM3UTRKV1d6d0FsNmZuSWNGd1o2blp5UjFQWXc5ZktxNndJTGZXTFRYS2tVZnk1SngrUFlnQnRjdjVtSzUzYUdKY0cvdjN6Qk9WbDdFT0hyZ2lPVkJkTUhtS1dCNnJJTHdwaERuNzhPT25VMzdxbHlRPT0=

To this format which is the same as the other landing pages currently in use:

go.php?CID=416071&bhu=spctECr16tLfm14ZpdEZurodvXKKKLDhqn5feD

This could indicate a change in affiliate networks or a change in the way the affiliate network handles their tracking. While unraveling all of these threads, I stumbled upon an entirely separate industry for just this aspect of affiliate marketing and from what I observed, it was just as equally shady.

The “CID” here in the last example is likely used to represent “Customer ID” for the affiliate tracking and could prove useful for mapping actors out, even if we don’t know who it actually is. From the 575 sites that I was able to get the source HTML for, there were four CID’s in use across the campaigns spanning 2 years.

- 411308

- 414300

- 414752

- 416071

Sales Pages

The sales pages weren’t initially interesting to me given that the illegal activity seems focused in the affiliate arena, but that changed fairly quickly when I began trying to understand more about the core workings of the campaigns.

For the “PureFit Keto” product, you’ll be presented with a page that looks like the below.

Figure 11. PureFit Keto sales page

On the surface, it’s pretty straight forward. Lots of meaningless slogans and visual alert cues to try and persuade you into giving them money and buying the pills.

After being sent the CaesarV article previously mentioned, I wondered if there were other blogs or posts about these campaigns that could shed more light on the situation.

Back in 2016 MalwarebytesLabs researcher Jovi Umawing released an article about the Stephen Hawking page selling “Inteligen” (the miracle brain formula). One thing that caught my eye here was the sales page for this product.

Figure 12. Inteligen sales page

It looks very familiar. The three checks, a pill bottle, the input dialog, “rush my order”, etc. Given their penchant for templates, I wondered if other sites were the same.

Of course, not too long after, I found other articles from Jovi dating all the way back to 2014. In both, there is a TMZ page selling a weight loss product called “Garcinia Cambogia.”

Figure 13. TMZ pre-sell page

This was coupled with other screenshots Jovi provided for the sales pages that users were redirected to when clicking on any of the links.

Figure 14. Garcinia Cambogia sales page variant 1

Along with…

Figure 15. Garcinia Cambogia sales page variant 2

Again, having them lined up next to each other helps to illustrate the obvious template being used when building these sales page. All the way down to the “IN STOCK” warning banners across the top that can be seen on the most recent “PureFit Keto” site. It also shows that, for at least 4 years now, they’ve been creating the templates in parallel to the fake celebrity endorsement pre-sell sites.

After reviewing a few more articles I found regarding these campaigns, with the earliest dating back to mid-2013, I began to look at the actual sales page URLs and corresponding meta-data to see if anything stood out.

Keep in mind that in this chain of events, the “affiliates” are the individuals pushing the initial enticements, such as the e-mail spam. There is a demarcation that occurs in affiliate marketing at the point of the sales pages which appear to be run by the “merchants” who sell the products and provide the pre-sell pages for affiliates to use.

They, of course, can be one in the same person but I wanted to try and understand the other side of the fence since they are so entwined with the deceptive marketing side of the campaign.

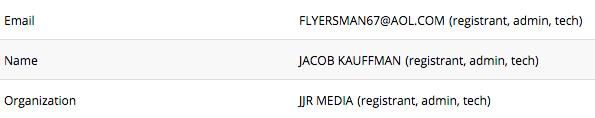

Looking at the sites from the campaigns I was observing, both “inteligen[.]org” and “purefitketo[.]net” didn’t provide anything of note; however, the site, “naturalgarciniacambogia[.]net”, from Jovi’s blog over at MalwareBytes did.

Back on January 22 2016, about 6 days before removing their details, a WHOIS record revealed the name, e-mail, and organization which registered that particular domain.

Figure 16. WHOIS for "naturalgarciniacambogia[.]net"

JJR Media

To kick things off, I did a quick Google search for the “JJR Media” organization and immediately found its website, with plenty of examples on display of their sales pages.

Figure 17. JJR media website

They have multiple products listed, all with similar templates, and even a slightly modernized version of their older Garcinia sales page.

Figure 18. Updated Garcinia sales page

Of course, two hits on Google below the one for their main website you find one for the Better Business Bureau (BBB) and complaints against the “naturalgarciniacambogia[.]net” website. It provides more details on the actual business organization behind the web site, which I was surprised to find was incorporated. I’ve since learned that one of the driving factors that these affiliate marketers have in incorporating their businesses is so they, the individual, cannot be held personally liable when people start going after them for fraud and the like.

These websites are hosted alongside an affiliate marketing network for a business called “Express Revenue Inc.”, which, if you pivot further on the domains hosted by these organizations, you can see multiple sales pages like the ones discussed in this blog.

Figure 19. JJR Media passive nameserver

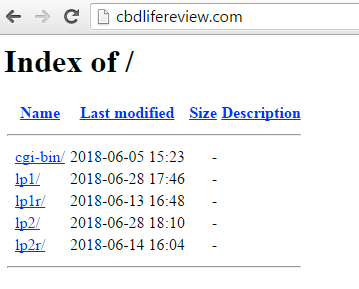

Focusing on the website “cbdlifereview[.]com”, which appears as though it is still being setup, it exposes an open directory of folders on the website.

Figure 20. Index of "cbdlifereview[.]com"

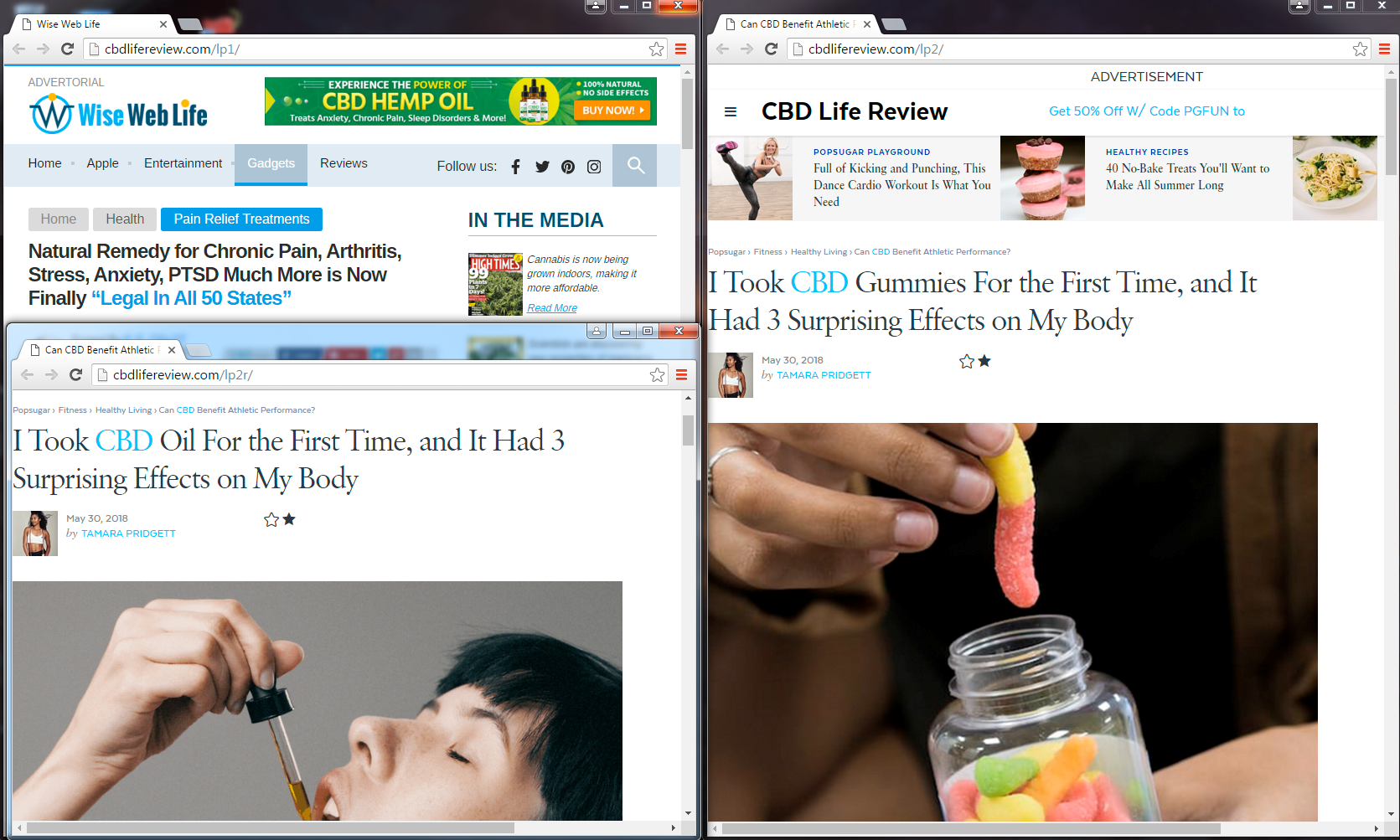

Each of these “lp” (landing pages) are the exact same deceptive pre-sell pages as described above by the FTC.

Figure 21. Jacobs CBD pre-sell pages

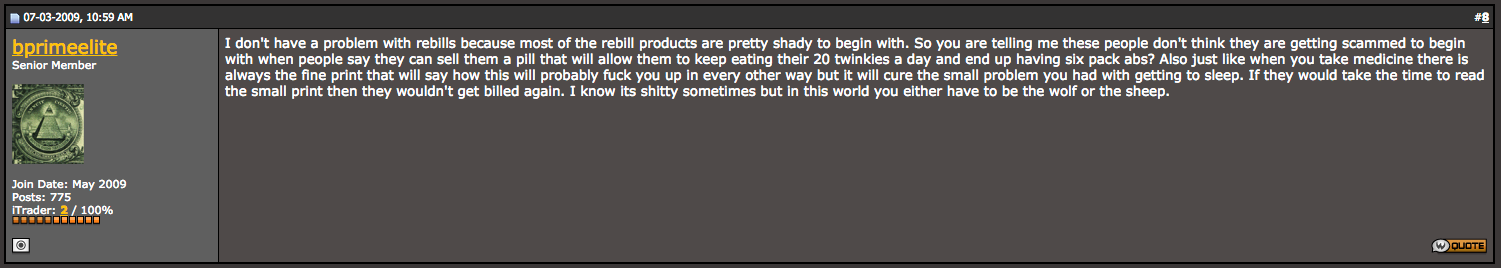

Additionally, the below image shows an affiliate “offer” site, wherein we can see that Express Revenue is offering to affiliates the Shark Tank pre-sell pages from advertiser “SLA Slim Quick” for campaigns.

Figure 22. Express Revenue Shark Tank

The FTC, Oprah, Dr. Oz, and NBC

Affiliate marketing scams like this are not new. Back in 2009, Oprah and Dr. Oz filed a lawsuit against hundreds of affiliates using the same type of “pre-sell” deceptive celebrity endorsement pages, which made national headlines. By 2014, the FTC was dragged front and center because of these fraudulent campaigns. There were literally thousands of these sites and affiliates, but I think it’s clear that the work done back this has done little to curb this still rampant activity.

From the FTC’s website on the event:

“Not only did these defendants trick consumers with their phony weight loss claims, they also compounded the deception by advertising on pretend news sites, making it impossible for people to know whether they were seeing news or an ad,” said Jessica Rich, Director of the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection.

As I was investigating all of these campaigns, I shared frequent screenshots and updates of interesting tidbits with the rest of my team. A funny thing happened a few months ago when one of them was watching the Today show on NBC, who is the current pre-sell flavor of the week, and they ran a segment on this exact campaign. My colleague sent me a link to the video and in turn, an article they published about it.

In this case, the sales page was trying to sell a skin care product called “Liva Derma Serum” and it was brought to the attention of the shows frontrunner by a fan asking if it was real, and subsequently investigated by Gadi Schwartz and Lindsey Bomnin.

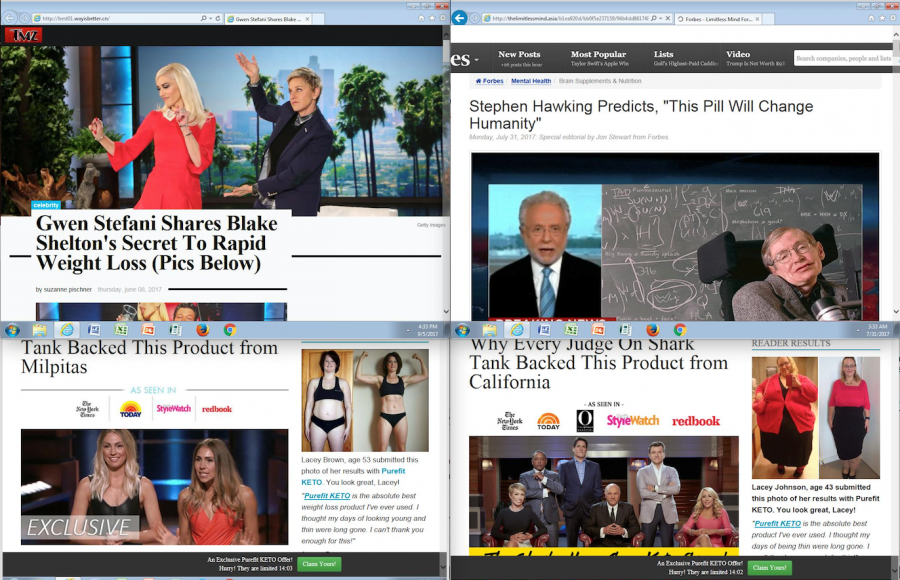

Now, before we continue on with this exploration, the next term we need to learn is “re-bill” and how it’s abused in this industry as a mechanism to scam people. That’s effectively what all of these campaigns are and, based on reading discussions in affiliate marketing communities, it’s one of the bigger cash cows.

Another Bill, Sir?

After you’ve lured the victim to your website, in tiny fine print that will never be seen, you include a line that says “if you don’t cancel your subscription within X days then you’ll be billed an absorbent amount of money on a reoccurring basis until you cancel.” You entice them with free products, or a trial run, to get your hooks in and then after they cover the initial cost of shipping, you slap them with large charges directly to their credit cards which may go unseen for multiple billing cycles.

Hopefully someone notices before it’s too late but more often than not, at least one cycle goes through and the merchants laugh all the way to the bank. At some point in the past, seemingly all of the affiliate marketing scams basically switched to this scheme because the payouts are bigger and there may be some legal wiggle-room due to that fine print. Every campaign described in this blog is a re-bill scam. Heck, even the affiliates know it’s unscrupulous but, as “bprimeelite” so tastefully stated: “in this world you either have to be the wolf or the sheep”.

Figure 23. Re-bill scam acknowledgement

To recap then –

- You have affiliates who spam links to get people to the pre-sell/landing pages and get paid a small amount of money for every user who successfully submits a valid credit card.

- You have “merchants” who run the re-bill scheme and potentially make $50-$100 per surprise credit card billing.

- You have an affiliate network which connects the merchants to the affiliates and acts as an intermediary who gets a piece of the pie from the merchants.

Looking at the Better Business Bureau’s (BBB) website provides a wealth of information on these affiliate networks and merchant businesses. It’s not uncommon to see warning like this for consumers:

BBB files indicate that this business has a pattern of complaints concerning: business not refunding the costumer and continued billing without customers knowledge. On July 7, 2014, the BBB sent a request to the business to address this pattern and what actions the business has taken to help eliminate the causes of complaints.

These BBB complaints highlight the “re-bill” scam in full effect.

01/13/2017

I signed up for a trial offer and they tried to charge my account $120 at two separate times. Notice this morning on January 13th 2017 that my account had been charged for $90 from this company. Then I proceeded to call the company and tell them that I had signed up for the trial that they had going on for $4.95.

12/12/2016

This company operates with deceitful business practices. They offer you a "free" product. You only have to pay minimal shipping. The free product enrolls you in an auto refill system and if you do not cancel your membership (that you are unaware you have) within 14 days you are charged $89.99 a month for additional product. On top of the hassle of unwittingly being charged for it, THEIR PRODUCT DOES NOT WORK!!

09/13/2016

I thought this was free, only had to pay 4.94 for shipping. I feel I was mislead.They have charged my account 89.99 for one bottle.Their advertising I received email saying free products of your choosing, all you had to do was pay for shipping.

All of this is allowed by the following line in the terms of service on the sales pages after you click a tiny link towards the bottom of the page.

I UNDERSTAND THAT THIS CONSUMER TRANSACTION INVOLVES A NEGATIVE OPTION AND THAT I MAY BE LIABLE FOR PAYMENT OF FUTURE GOODS AND SERVICES, UNDER THE TERMS OF THIS AGREEMENT, IF I FAIL TO NOTIFY THE Garcinia Active Slim NOT TO SUPPLY THE PRODUCTS DESCRIBED. BY PLACING MY ORDER, I PROVIDE MY ELECTRONIC AUTHORIZATION FOR FUTURE CHARGES AGAINST MY CREDIT CARD UNLESS I CANCEL. IN ADDITION, YOU DO NOT HOLD Garcinia Active Slim RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY OVERDRAFT CHARGES OR FEES THAT YOU MIGHT INCUR DURING THE ONGOING AUTO-SHIP PROGRAM.

Takedown Cures

This brings us to the question of “what can be done about it?” and unfortunately, the reality is there isn’t much beyond education, which this blog attempts to provide to the reader.

The FTC is aware and the celebrities and organizations being used are aware with some having taken legal action, but it still remains as problematic as ever - so what else can be done?

Well, as part of this research and data collection, after identifying a reoccurring pattern of abuse of GoDaddy services, I reached out to their Threat Intelligence team to see if we couldn’t tackle at least one aspect of these campaigns and hinder the perpetuation of the scams.

After writing some new scripts to automate and collect shadow domains for these campaigns and working with GoDaddy’s abuse teams, we were able to successfully identify and shut down over 15,000 subdomain being used across these campaigns.

Based on what we know from the dozens of publicly available “bit.ly” and “goo.gl” statistics of the initial URLs being spammed out to our customers, we are able to glean a little insight into the potential disruption this shutdown may have. On average, primarily with viewers from the United States of America, the links were each clicked 273 times. If even a fraction of the 15,000 plus subdomains received that many clicks per site, then it removed millions of potential targets these actors could prey upon.

A big win for everyone involved that will go a long way in protecting consumers.

Conclusion

Throughout this blog, I’ve tried to stress the importance of patterns at every phase of analysis to establish the behaviors for how these affiliates, networks, and merchants operate. The Internet has proved to be a breeding ground for nefarious activity and with so many moving parts, it constantly makes attribution and accountability more complicated.

While pouring over the forums, both private and public, for these affiliate marketers, you find that they are all very aware of the fraud that is rampant in their industry. In a lot of cases, they are even openly flaunting their “black hat” activities. They know that due to the anonymous nature of the Internet, the difficulty that the U.S. Government has faced when trying to prosecute these crimes, and how easy it has become to blend into the every-day background noise, there appears to be little risk to them for continuing with these scams.

It’s unfortunate to see how pervasive this advertising industry has become and it doesn’t appear to be slowing down anytime soon as long as the money keeps flowing in.

There are a lot of players in the affiliate marketing world, from the affiliates to the merchants and all of the networks in-between. Hopefully this blog helps to shine some light on how at every link in this chain there are shady, sometimes illegal, and almost always deceptive, business practices still being employed to scam hard working people out of their money.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.