This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

In recent years containers have become increasingly popular. A few years ago Microsoft realized that and teamed up with Docker to offer a container solution for Microsoft Windows.

Judging by the number of severe vulnerabilities found in containers for Linux in recent years, it is likely that some vulnerabilities exist in containers for Windows as well. Windows, unlike Linux, is not open-source and because the container feature, in particular, is barely documented it is much more difficult to find said vulnerabilities. Currently, there is little information about the internal implementation of the feature in Windows. Reverse engineering the kernel was needed to better understand Microsoft’s implementation of containers.

I’ve found that job objects are used in a similar way control groups (cgroups) are used in Linux, and that server silo objects were used as a replacement for namespaces support in the kernel. Furthermore, I found out that Windows filters system calls in kernel space, thus preventing a container process from escalating its privileges and escaping the container. This post demonstrates we can learn a lot from reverse engineering Windows containers. Further research could help us better understand the threat model of Windows containers.

Some History

Until Microsoft teamed up with Docker, Windows was lacking some of the core features that were needed in order for containers to work properly, mainly namespaces, control groups (cgroups) and layer capabilities. After two and a half years of development and another year of beta testing in Microsoft’s Windows Insider Program, in September 2016, Microsoft announced that containers would be supported in the upcoming Windows Server 2016.

Namespaces were originally a unique feature for Linux providing a way to control what resources with which a process can interact. They are quite different from access controls because the process doesn’t know the resources exist. A simple example of this is the process list: there could be 100 processes running on a server, yet a process running within a namespace might see only 10 of those. Another example might be for a process to think it’s reading from the root directory when in fact it has been virtualized. In 2006, the Linux kernel was added the support for grouping processes together under a common set of resource controls in a feature called cgroups. It’s the combination of cgroups and namespaces that became the foundation of modern-day containers.

Luckily for Microsoft, Windows already had a control groups-like feature called job object. A job object allows groups of processes to be managed as a single unit. Examples include enforcing limits such as working set size and process priority or terminating all processes associated with a job. Microsoft was still missing a namespace-like feature, and so a kernel object called a silo was born.

The Result

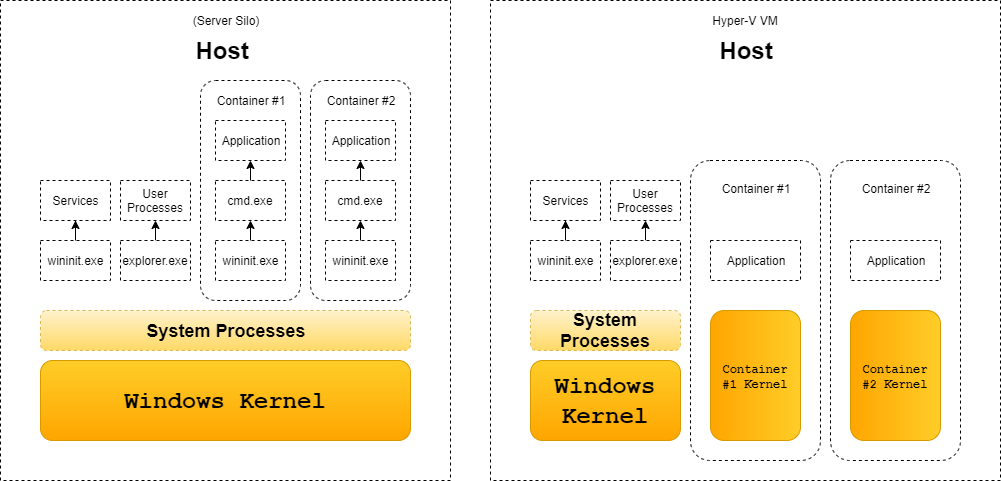

Microsoft introduced two types of container architectures, shown in Figure 1:

- Deploying an application in a fully isolated, Hyper-V virtual machine, which is supported on both Windows 10 and Windows Server.

- Deploying an application in a lightweight silo container, which is currently supported only in Windows Server.

The first design is using a Virtual Machine (VM): the container(s) will have a separate kernel. This solution has two sub-solutions:

- Linux containers in a Moby VM: This is a full-sized VM. In this model, Docker runs on the Windows desktop but calls into Docker Daemon on the Linux VM.

- Hyper-V Isolation: Microsoft calls this “Linux containers on Windows” (LCOW). In this technique, the Linux VM got only the very basic internals that is absolutely necessary to run containers. In contrast to the Moby VM approach, each Linux container has its own kernel and its own VM sandbox.

In this post, I focus only on the second, silo container solution, which uses the host’s Windows kernel.

Figure 1. Server silo container vs HyperV

Implementation Details

Virtual File System and Registry

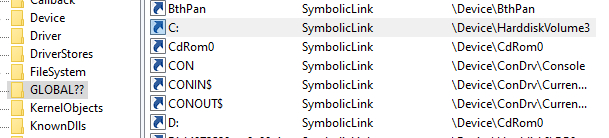

Without getting too deep into the implementation of Windows’ file system, every file access in Windows goes through a symbolic link. When a user calls CreateFile (which is an API function to get a handle to a file) for C:\secret.txt the C: part is just a symbolic link to something like \Device\HarddiskVolumeXXX\. When a process from inside a container tries to access C:\secret.txt the path is then converted to something like \Device\VhdHardDisk{123651}\ instead of the above. The exact same thing happens for registry keys. This mechanism is covered later in the article.

Figure 2. WinObj showing C: is just a symbolic link

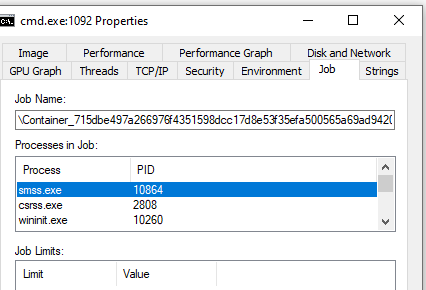

Jobs

Jobs, or job objects are not a new feature and in fact were a part of Windows at least since Windows 2000. According to Microsoft, a job object allows groups of processes to be managed as a unit. Job objects are namable, securable, sharable objects that control attributes of the processes associated with them. Operations performed on a job object affect all processes associated with the job object. In our case, the main job of the job object is to limit resources for the container. Job objects are used for far more features than just containers, and that’s why they were introduced long before containers were born. Some of the main restrictions you can apply to a group of processes using job objects are:

- Maximum number of active processes: This limits the number of concurrently existing processes in the job and can be used to limit the number of processes a container can have. New processes that exceed the limit are blocked from creation.

- Across job CPU limitation: this parameter is used to limit the CPU time of all the processes in the job combined. Once a process exceeds the limitation all the processes in the job will be terminated.

- Per process CPU limitation: this parameter is used to limit the CPU time for each process individually. Once a process exceeds the limit it will be terminated.

- Process and job virtual memory limit: this parameter is used to limit the amount of virtual memory that can be allocated by either a single process or the entire job.

- Network bandwidth rate control: this parameter sets the maximum outgoing bandwidth for the entire job, after the maximum outgoing bandwidth has been reached, throttling takes effect.

- Disk I/O bandwidth rate control: this parameter is exactly the same as the network bandwidth just for disk I/O.

Figure 3. ProcessExplorer showing a job of inside-a-container process

Server Silos

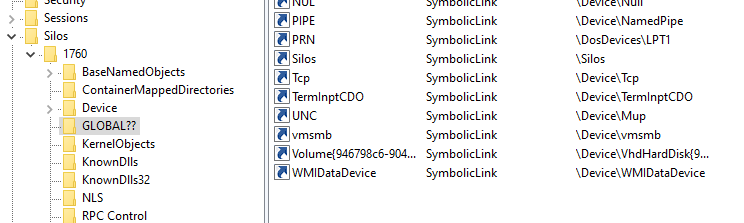

Server silos are the main feature that allows Windows to have isolation good enough for a full container solution. For a better understanding of what server silos are, I first need to explain what a root directory object is. Without getting too much into the mechanism, enough to say that most of the named objects in Windows (files, registry, symbolic links, pipes, etc.) are under a root namespace called the root directory object. When a silo is created, another root directory object is created for that silo. From that point on, there is a different value for any named object (for example, the symbolic link “C:”).

Figure 4. WinObj showing a root directory object of a silo

Reverse Engineering

The information presented so far is described in official Microsoft documentation or other sources available to the public. However, some questions relating to the implementation of Windows containers are left unanswered by these sources. I decided to reverse engineer these parts to better understand how Windows containers are built. Some of the main questions I approached in my research were:

- How does the kernel distinguish between containerized and normal processes?

- How does the kernel provide access to files and registry within the container and not the host?

- How does the kernel prevent the container from access to certain system calls such as loading kernel drivers?

I briefly answered some of those questions in the last section. In this part, I will get into more details and show some actual code from the kernel.

How Does the Kernel Distinguish Container Processes?

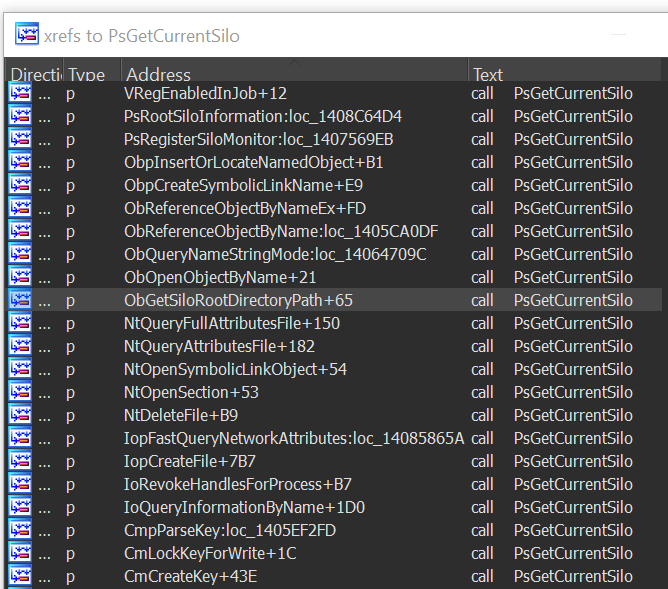

There are plenty of functions in the Windows kernel used to distinguish between processes and threads inside a container from those which are outside. Some of them are PsIsCurrentThreadInServerSilo, PsGetCurrentSilo and more. An interesting thing to observe is where those functions are called from; these places in the code may be where the kernel distinguishes between containerized processes and regular processes.

Figure 5. Some of the kernel functions that check if the process is in a container

How Does the Kernel Recognize Container Access to Files?

None of the checks related to identifying a containerized process happen in user mode. The kernel is responsible for distinguishing between operations of regular processes and container processes, including access to files.

First I have to briefly explain about system calls in Windows. Unlike Linux, applications don’t use system calls directly but rather call API functions that are delivered through internal DLLs. Some of those DLLs are not documented. Those functions call other API functions and which may themselves call others until eventually, the system call occurs.

One might think that somewhere along the road from the API function call to the kernel the container\silo check is handled. It isn’t. To be clear: if a process host.exe executes CreateFile(“C:\secret.txt”) from the host, and a process container.exe executes CreateFile(“C:\secret.txt”) from the container - both of them will get to NtCreateFile in the kernel with exactly the same parameters.

So, What Does Happen in the Kernel When Accessing a File?

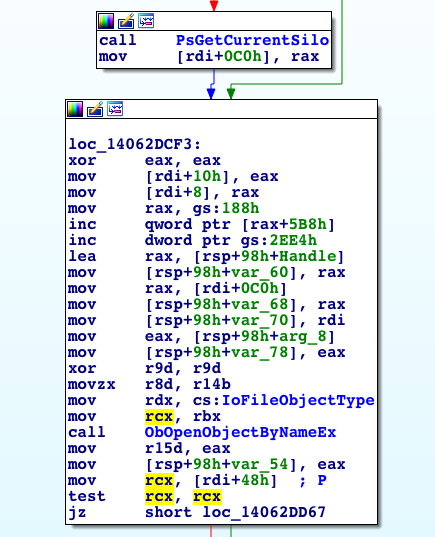

Once we arrive to kernel land, our first stop is NtCreateFile . This function doesn’t do much by itself and simply calls IopCreateFile. In IopCreateFile the kernel starts handling silos by first checking if the current thread is attached to a silo. This check is done by calling the PsGetCurrentSilo function. This routine returns the current silo for the calling thread, specifically a pointer to the ESILO object or null, if the thread is not attached to a process in a silo.

Figure 6. A snippet from IopCreateFile showing the kernel handling silos

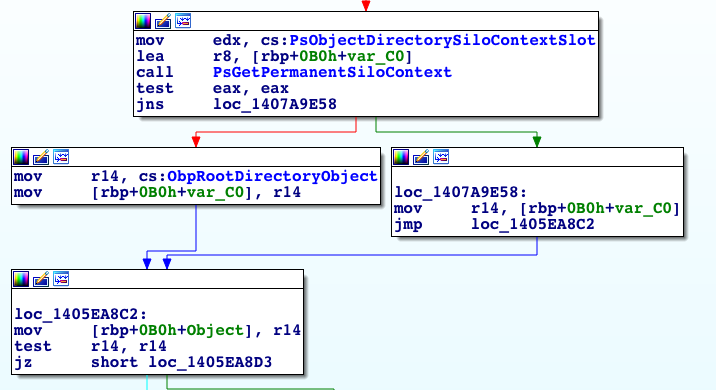

The pointer to the ESILO object is then forwarded to ObOpenObjectByNameEx which forwards it to ObpLookupObjectName. The most relevant part of ObpLookupObjectName is the part where it chooses the ObpRootDirectoryObject.

Figure 7. The RootDirectoryObject is chosen

With the last part we can get a pretty good idea of how things work. At the beginning of the post I explained how symbolic links are parsed from the root directory object. Now we have the last piece of the puzzle by understanding how the root directory object is being selected for each I/O request.

How Does the Kernel Prevent Container Access to Certain System Calls?

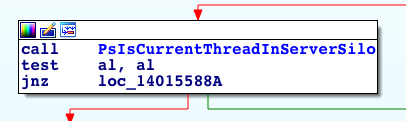

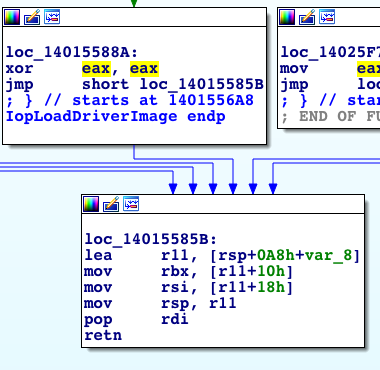

There are plenty of dangerous system calls and more than one kernel function to determine if the calling process or thread is inside a silo. For the specific case of loading drivers inside containers, I have found out that Windows does have a sufficient check in the kernel, which is relevant for many other system calls as well. In this case, IopLoadDriverImage which is the function NtLoadDriver calls to actually load a kernel driver image, simply returns a value indicating whether the calling process is inside a silo.

Figure 8. IopLoadDriverImage returning if the thread is in a silo

Some Security Concerns

When I started researching containers for Windows I was very curious about how Microsoft chose to handle access to the file system and dangerous system calls. The user inside the container is usually an administrator and has no limitations on the system calls he can execute. I was wondering what prevents a malicious container from loading a kernel driver, for example. Since the check is implemented per system call, it would be interesting to look into each specific implementation and audit for any possible mishandlings that could lead to security issues.

Summary

The information presented in this post is just the tip of the iceberg. I hope this post will encourage others to learn and write about containers for Windows.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.