This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

In March 2021, I uncovered the first known malware targeting Windows containers, a development that is not surprising given the massive surge in cloud adoption over the past few years. I named the malware Siloscape (sounds like silo escape) because its primary goal is to escape the container, and in Windows this is implemented mainly by a server silo.

Siloscape is heavily obfuscated malware targeting Kubernetes clusters through Windows containers. Its main purpose is to open a backdoor into poorly configured Kubernetes clusters in order to run malicious containers.

Compromising an entire cluster is much more severe than compromising an individual container, as a cluster could run multiple cloud applications whereas an individual container usually runs a single cloud application. For example, the attacker might be able to steal critical information such as usernames and passwords, an organization’s confidential and internal files or even entire databases hosted in the cluster. Such an attack could even be leveraged as a ransomware attack by taking the organization's files hostage. Even worse, with organizations moving to the cloud, many use Kubernetes clusters as their development and testing environments, and a breach of such an environment can lead to devastating software supply chain attacks.

Siloscape uses the Tor proxy and an .onion domain to anonymously connect to its command and control (C2) server. I managed to gain access to this server. We identified 23 active Siloscape victims and discovered that the server was being used to host 313 users in total, implying that Siloscape was a small part of a broader campaign. I also discovered that this campaign has been taking place for more than a year.

This report provides background on Windows container vulnerabilities, gives a technical overview of Siloscape and offers recommendations on best practices for securing Windows containers.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected from this threat with Prisma Cloud’s Runtime Protection features.

Windows Server Container Vulnerabilities Overview

On July 15, 2020, I released an article about Windows container boundaries and how to break them. In that article, I presented a technique for escaping from a container and discussed some potential applications that such an escape can have in the hands of an attacker. The most significant application, and the one I chose to focus on, was an escape from a Windows container node in Kubernetes in order to spread in the cluster.

Microsoft originally didn’t consider this issue a vulnerability, based on the reasoning that Windows Server containers are not a security boundary, and therefore each application that is being run inside a container should be treated as if it is executed directly on the host.

A few weeks after that discussion, I reported the issue to Google because Kubernetes is vulnerable to those issues. Google contacted Microsoft, and after some back and forth, it was determined by Microsoft that an escape from a Windows container to the host, when executed without administrator permissions inside the container, will in fact be considered a vulnerability.

Following this, I discovered Siloscape, which is malware that actively attempts to exploit Windows Server containers in the wild. Siloscape is heavily obfuscated malware targeting Kubernetes through Windows containers (using Server Containers and not Hyper-V). Its main purpose is to open a backdoor into poorly configured Kubernetes clusters in order to run malicious containers such as, but not limited to, cryptojackers.

The malware is characterized by several behaviors and techniques:

- Targets common cloud applications such as web servers for initial access, using known vulnerabilities (“1-days”) – presumably those with a working exploit in the wild.

- Uses Windows container escape techniques to escape the container and gain code execution on the underlying node.

- Attempts to abuse the node's credentials to spread in the cluster.

- Connects to its C2 server using the IRC protocol over the Tor network.

- Waits for further commands.

This malware can leverage the computing resources in a Kubernetes cluster for cryptojacking and potentially exfiltrate sensitive data from hundreds of applications running in the compromised clusters.

Investigating the C2 server showed that this malware is just a small part of a larger network and that this campaign has been taking place for over a year. Furthermore, I confirmed that this specific part of the campaign was online with active victims at the time of writing.

Technical Overview

Before diving into the technical details of Siloscape, it is important to get a better understanding of its overall behavior and flow.

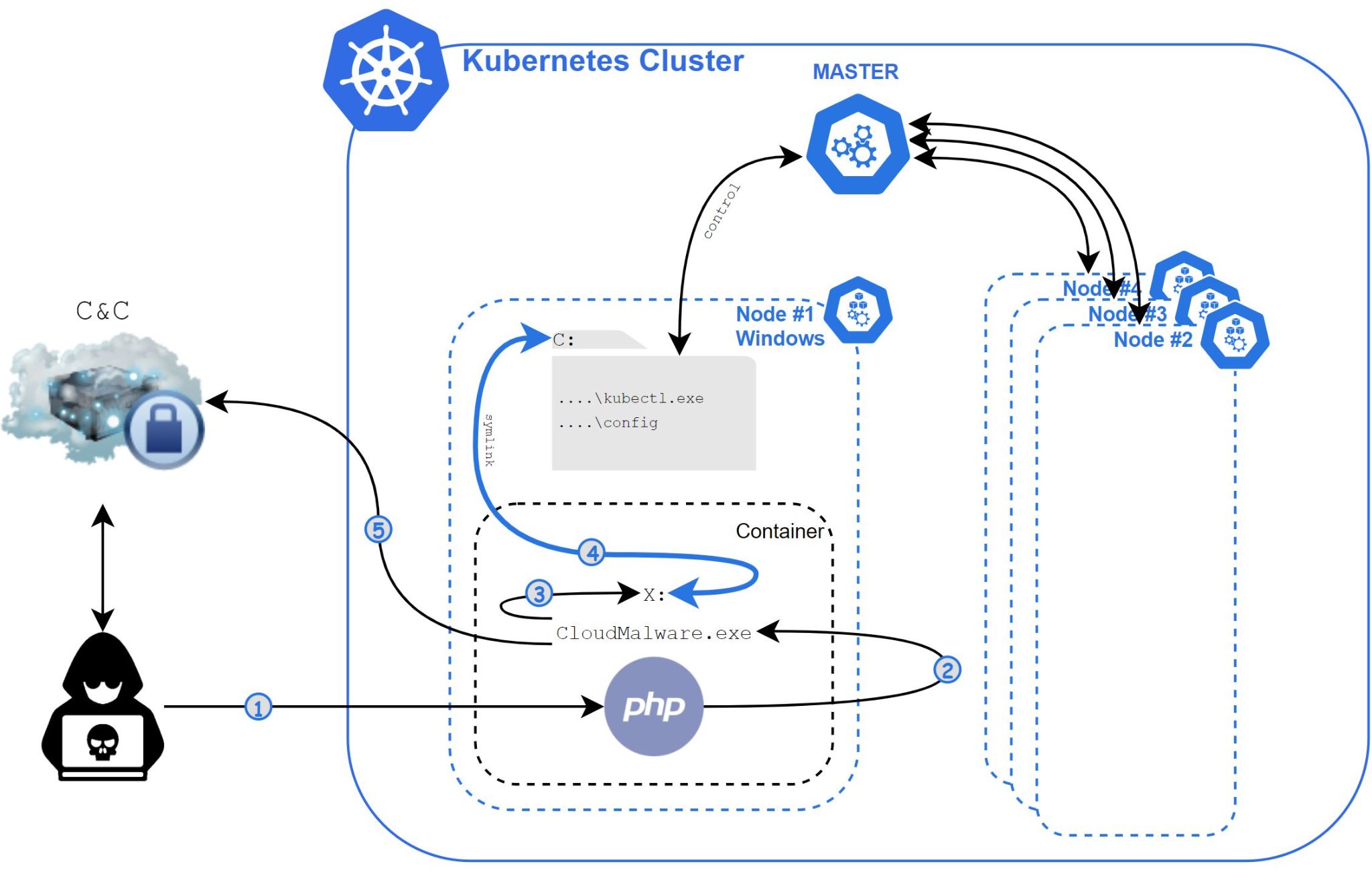

- The attacker achieves remote code execution (RCE) inside a Windows container using a known vulnerability or a vulnerable web page or database.

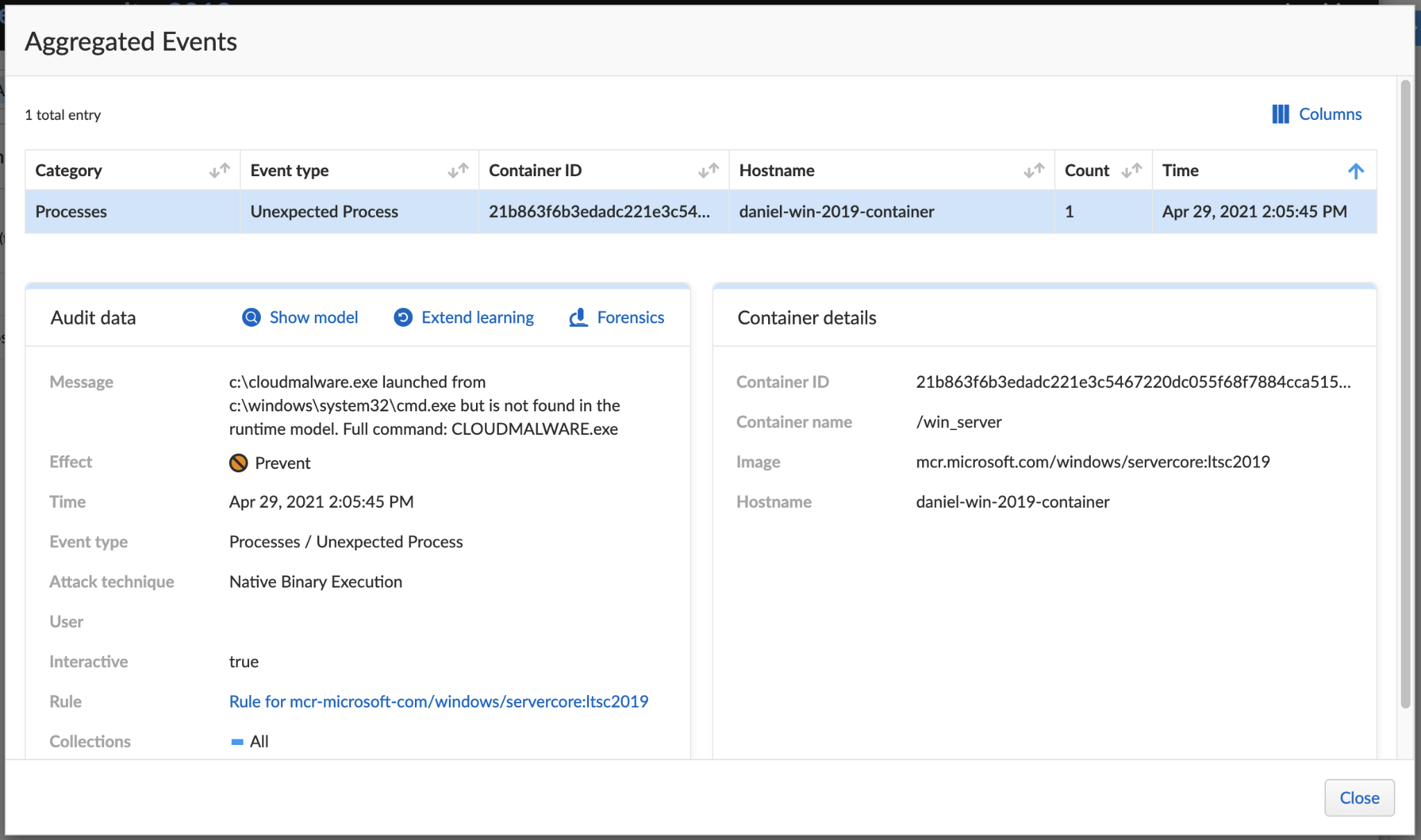

- The attacker executes Siloscape (CloudMalware.exe) with the necessary C2 connection information provided as command line arguments (and not hardcoded inside the binary).

- Siloscape impersonates CExecSvc.exe to obtain SeTcbPrivilege privileges (this technique is described in detail in my previous article).

- Siloscape creates a global symbolic link to the host, practically linking its containerized X drive to the host’s C drive.

- Siloscape searches for the kubectl.exe binary by name and the Kubernetes config file by regular expression on the host, using the global link.

- Siloscape checks if the compromised node has enough privilege to create new Kubernetes deployments.

- Siloscape extracts the Tor client to the disk from an archived file using an unzip binary. Both files are packed into the main Siloscape binary.

- Siloscape connects to the Tor network.

- Using the provided command line argument, Siloscape decrypts the C2 server’s password.

- Siloscape connects to the C2 server using an .onion domain (a domain accessible through the Tor network) provided as a command line argument.

- Siloscape waits for commands from the C2 and executes them.

Unlike other malware targeting containers, which are mostly cryptojacking-focused, Siloscape doesn’t actually do anything that will harm the cluster on its own. Instead, it focuses on being undetected and untraceable and opens a backdoor to the cluster.

Defense Evasion and Obfuscation

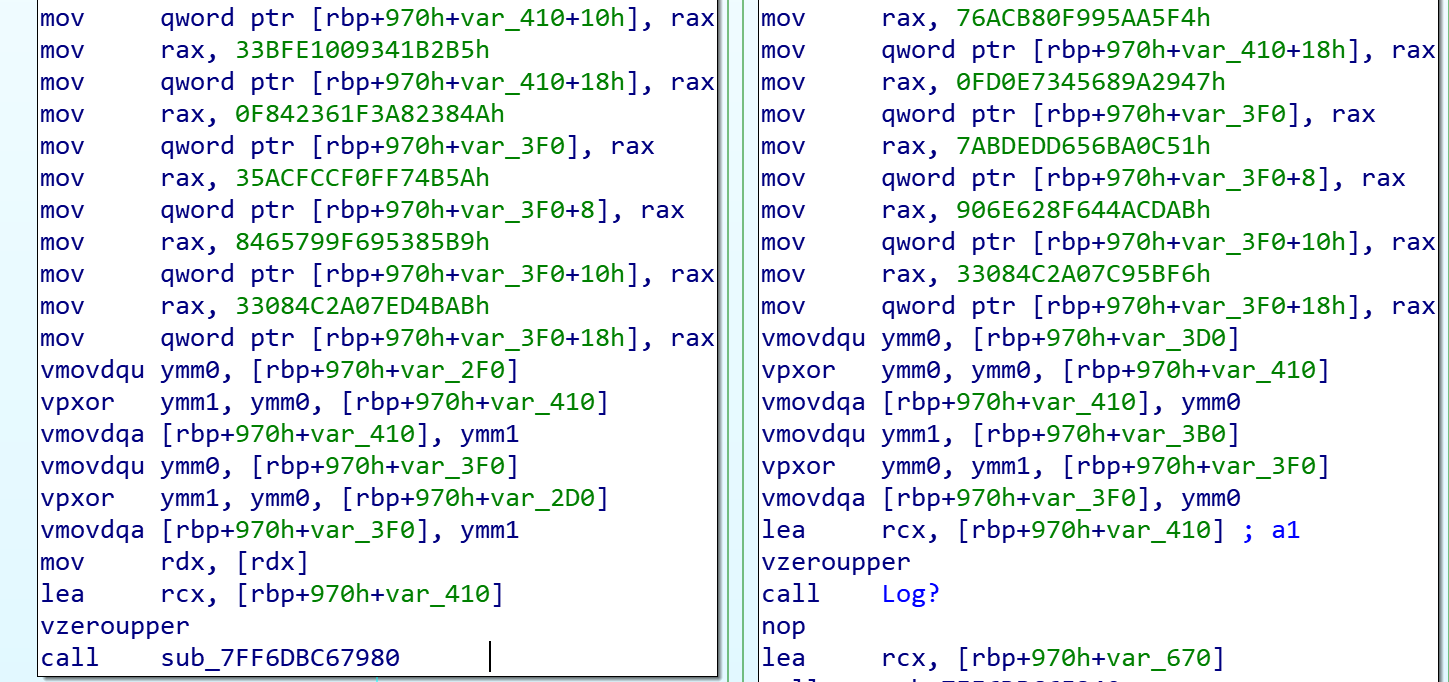

Siloscape is heavily obfuscated. There are almost no readable strings in the entire binary. While the obfuscation logic itself isn’t complicated, it made reversing this binary frustrating.

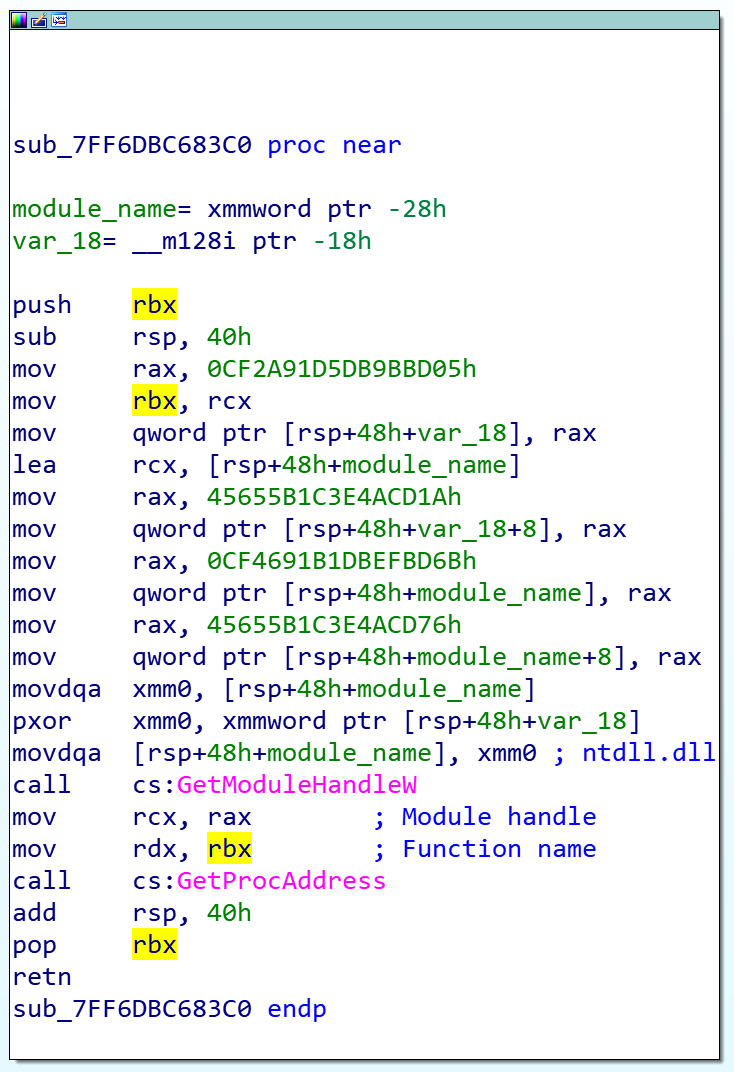

Even simple API calls were obfuscated, and instead of just calling the functions, Siloscape made the effort to use the Native API (NTAPI) version of the same function.

For example, instead of calling CreateFile, Siloscape calls NtCreateFile. Instead of calling NtCreateFile directly, Siloscape calls it dynamically, meaning it searches for the function name in ntdll.dll at runtime and jumps to its address. Not only that, but it also obfuscates the function and module names and deobfuscates them only at runtime. The end result is malware that is very difficult to detect with static analysis tools and frustrating to reverse engineer.

Siloscape uses a pair of keys to decrypt the C2 server’s password. One of the most important features of its obfuscation is that one key is hardcoded into the binary, while the other is supplied as a command line argument. I searched for its hash in multiple engines, such as AutoFocus and VirusTotal, and couldn’t find any results. This led me to believe that Siloscape is being compiled uniquely for each new attack, using a unique pair of keys. The hardcoded key makes each binary a little bit different than the rest, which explains why I couldn’t find its hash anywhere. It also makes it impossible to detect Siloscape by hash alone.

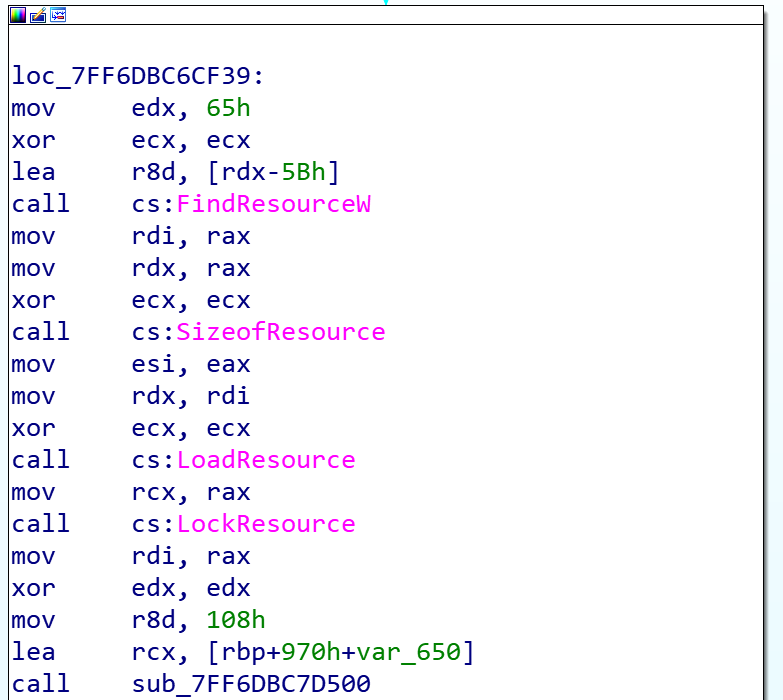

Another interesting technique this malware uses is Visual Studio’s Resource Manager. This is a feature built into Visual Studio that allows one to attach basically any file to the original binary and get a pointer to its data with a few simple API calls. Siloscape uses this method to write the Tor archive to the disk, as well as the unzip binary used to open the archive. It also uses Tor to securely connect to its C2.

The Container Escape

One of the more interesting things about Siloscape is the way it escapes the container. To execute the system call NtSetInformationSymbolicLink that enables the escape, one must gain SeTcbPrivilege first. There are a few ways to do this. For example, in my tests, I injected a DLL into CExecSvc.exe, which has the relevant privileges, and executed NtSetInformationSymbolicLink from the CExecSvc.exe context. Siloscape, however, uses a technique called Thread Impersonation. This method has little documentation online and even fewer working examples. The most critical function for this technique is the undocumented system call NtImpersonateThread.

Siloscape mimics CExecSvc.exe privileges by impersonating its main thread and then calls NtSetInformationSymbolicLink on a newly created symbolic link to break out of the container. More specifically, it links its local containerized X drive to the host’s C drive.

Choosing the Cluster

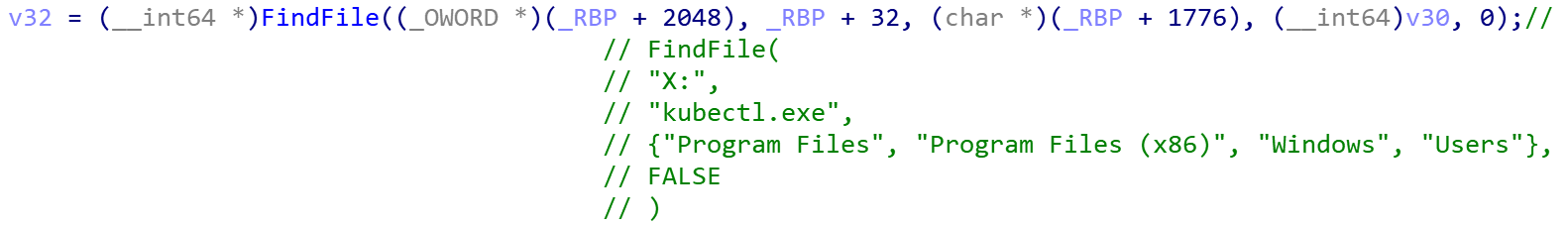

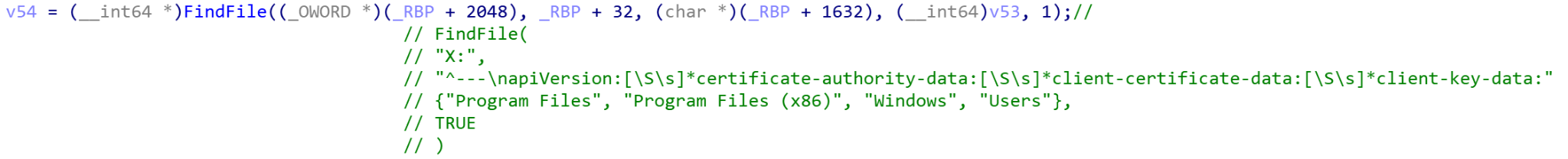

After Siloscape creates a link to the host, it will search for two specific files: kubectl.exe and the Kubernetes config file, which normally exists on Kubernetes nodes.

Siloscape searches for kubectl.exe by name and the config file using a regular expression. The search function takes an extra argument: a pointer to a vector that holds folder names to exclude from the search.

When it calls FindFile to search for the above files, it excludes the folders Program Files, Program Files (x86), Windows and Users. It does this to make the search faster and because it is unlikely the previously mentioned files are in those folders. If both files are found, their paths are saved to a global variable. If the files are not located, Siloscape exits, abandoning the attack.

After Siloscape finds everything it needs to execute kubectl commands, it continues to check if the compromised node actually has enough permissions to use for the attacker’s malicious activities. It does this by executing the kubectl command %ls auth can-i create deployments --kubeconfig=%ls where the strings in the format are replaced by the paths it saved earlier as global variables.

Connecting to the C2 and Supported Commands

After getting everything it needs and checking that the compromised node is indeed capable of creating new deployments, Siloscape writes the Tor archive (ZIP) and an unzip binary to the host’s C drive. After extracting Tor, it launches tor.exe to a new thread and waits for it to finish by checking the Tor thread output.

After Tor is up and running, Siloscape uses it to connect to its C2 – an IRC server, using an onion address that was provided as a command line argument.

The server is password-protected. Siloscape uses its first command line argument to decrypt the password by a simple byte by byte XOR. The following is a simplified version of the C2 server’s password decryption:

char hardCodedXor[32] = "HARD_CODED_32_LONG_STRING";

char ircPass[32] = { 0 };

for (int i = 0; i < 32; i++)

ircPass[i] = hardCodedXor[i] ^ argv[1][i];

Once successfully connected to the IRC server, it issues a JOIN #WindowsKubernetes command to join the WindowsKubernetes IRC channel and then idles there.

Siloscape allows two types of instructions, one for kubectl supported commands and one for regular Windows cmd commands.

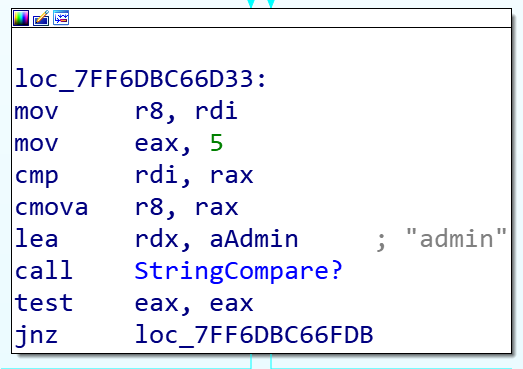

It waits for a private message. If one from a user named admin is received, Siloscape follows the following logic:

- If the message starts with a K, it executes a kubectl command to the cluster using the paths it found earlier by running the command %ls %s --kubeconfig=%ls where:

- The first parameter is the global variable of the kubectl’s path.

- The second parameter is the message from the admin minus the first character.

- The third parameter is the global variable of the config’s path.

- If the message starts with a C, it simply runs the command minus the first character as a regular Windows cmd command.

Command and Control

After I reversed the malware, especially the part that handles the C2, I wanted to discover whether this campaign was still up and running.

I set up a brand new virtual machine, downloaded Tor and started looking for an IRC client that supports SOCKS5, the proxy protocol that is needed in order to connect through Tor. IRC is a very old protocol and is less popular today than it was 20 years ago. Furthermore, IRC came out almost a decade before SOCKS5. I found HexChat, a simple, lightweight IRC client that supports both SOCKS5 and connecting to onion domains.

When our Silospace sample was originally executed, its command line argument for the IRC username was php_35, so I decided to use this username when connecting to the C2 server from HexChat, thinking it would appear legitimate to the attacker.

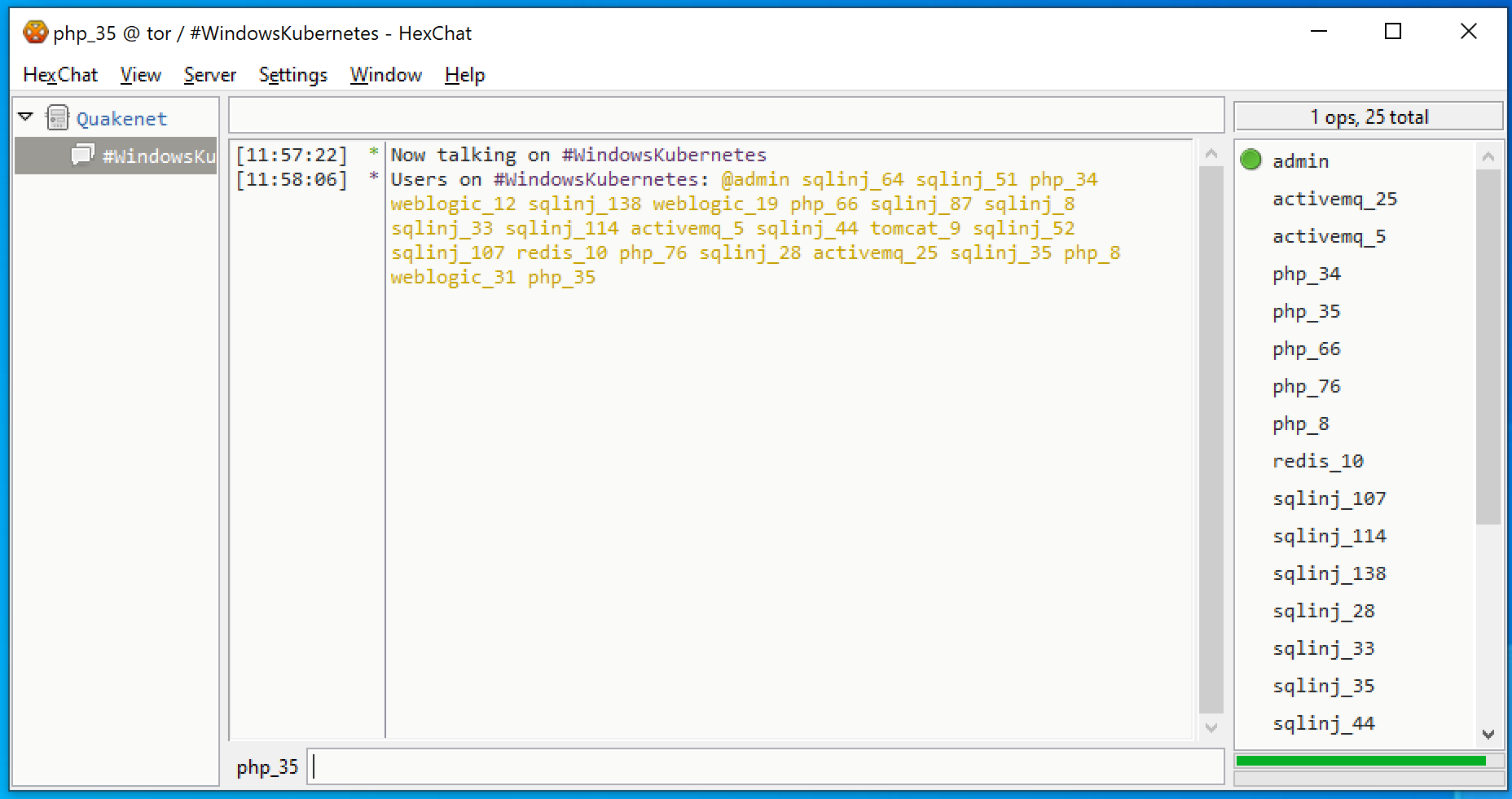

I connected to the server and discovered it was still working. I joined #WindowsKubernetes just like Siloscape does. There were 23 active victims there and a channel operator named admin.

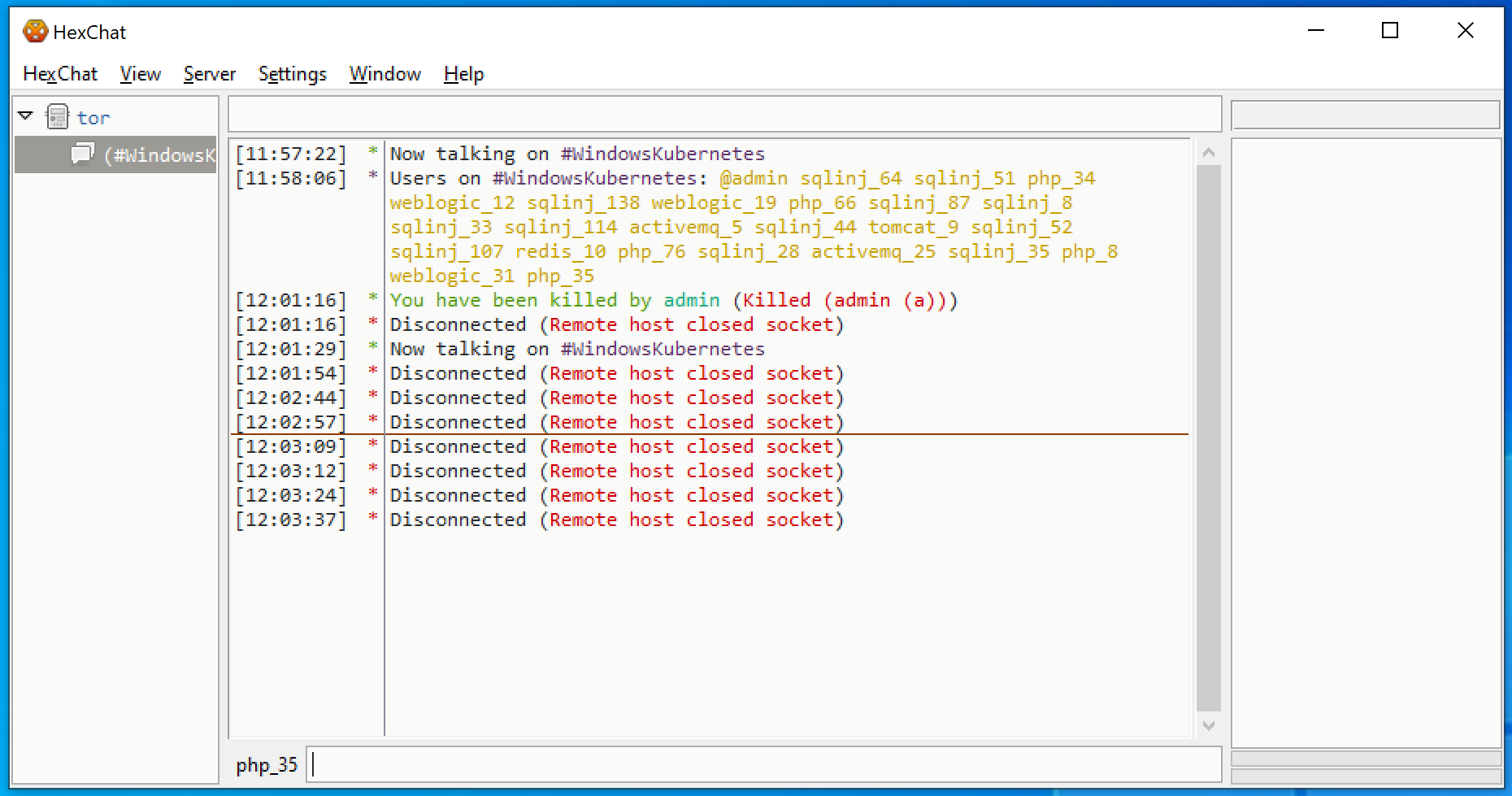

Unfortunately, after about two minutes, I was noticed and kicked out of the server. Two minutes after that, the server was no longer active – at least not at the original onion domain I used.

What Can We Learn?

When I went over my findings, the first thing that came to mind is that there were many more active users on the C2 server than I actually saw in the #WindowsKubernetes channel – 313 users in total, to be exact. This implies that the Siloscape malware was just a small part of a bigger campaign.

Sadly, when I connected to the server, the channels list was empty, indicating that the server was configured to not reveal its channels. Therefore, I couldn’t get more information from the channel names.

The second and more important detail that stood out was the convention used for the victims’ names. Our name was php_35, and when our sample of Siloscape first executed, it indeed was executed through a vulnerable php instance. The other names clearly suggest the way the attacker managed to achieve code execution (sqlinj probably means SQL injection):

@admin sqlinj_64 sqlinj_51 php_34 weblogic_12 sqlinj_138 weblogic_19 php_66 sqlinj_87 sqlinj_8 sqlinj_33 sqlinj_114 activemq_5 sqlinj_44 tomcat_9 sqlinj_52 sqlinj_107 redis_10 php_76 sqlinj_28 activemq_25 sqlinj_35 php_8 weblogic_31 php_35

The last piece of information I was able to obtain from the C2 is the creation date of the server: Jan. 12, 2020. Note that this doesn’t necessarily mean that Siloscape was created on that date. Instead, it’s likely the campaign started at that time.

Conclusion

Unlike most cloud malware, which mostly focuses on resource hijacking and denial of service (DoS), Siloscape doesn’t limit itself to any specific goal. Instead, it opens a backdoor to all kinds of malicious activities.

As discussed in my last article, users should follow Microsoft’s guidance recommending not to use Windows containers as a security feature. Microsoft recommends using strictly Hyper-V containers for anything that relies on containerization as a security boundary. Any process running in Windows Server containers should be assumed to have the same privileges as admin on the host, which in this case is the Kubernetes node. If you are running applications in Windows Server containers that need to be secured, we recommend moving these applications to Hyper-V containers.

Furthermore, administrators should make sure their Kubernetes cluster is securely configured. In particular, a secured Kubernetes cluster won’t be as vulnerable to this specific malware as the nodes’ privileges won’t suffice to create new deployments. In this case, Siloscape will exit.

Siloscape shows us the importance of container security, as the malware wouldn’t be able to cause any significant damage if not for the container escape. It is critical that organizations keep a well-configured and secured cloud environment to protect against such threats.

Existing Prisma Cloud capabilities will successfully detect and mitigate the Siloscape malware.

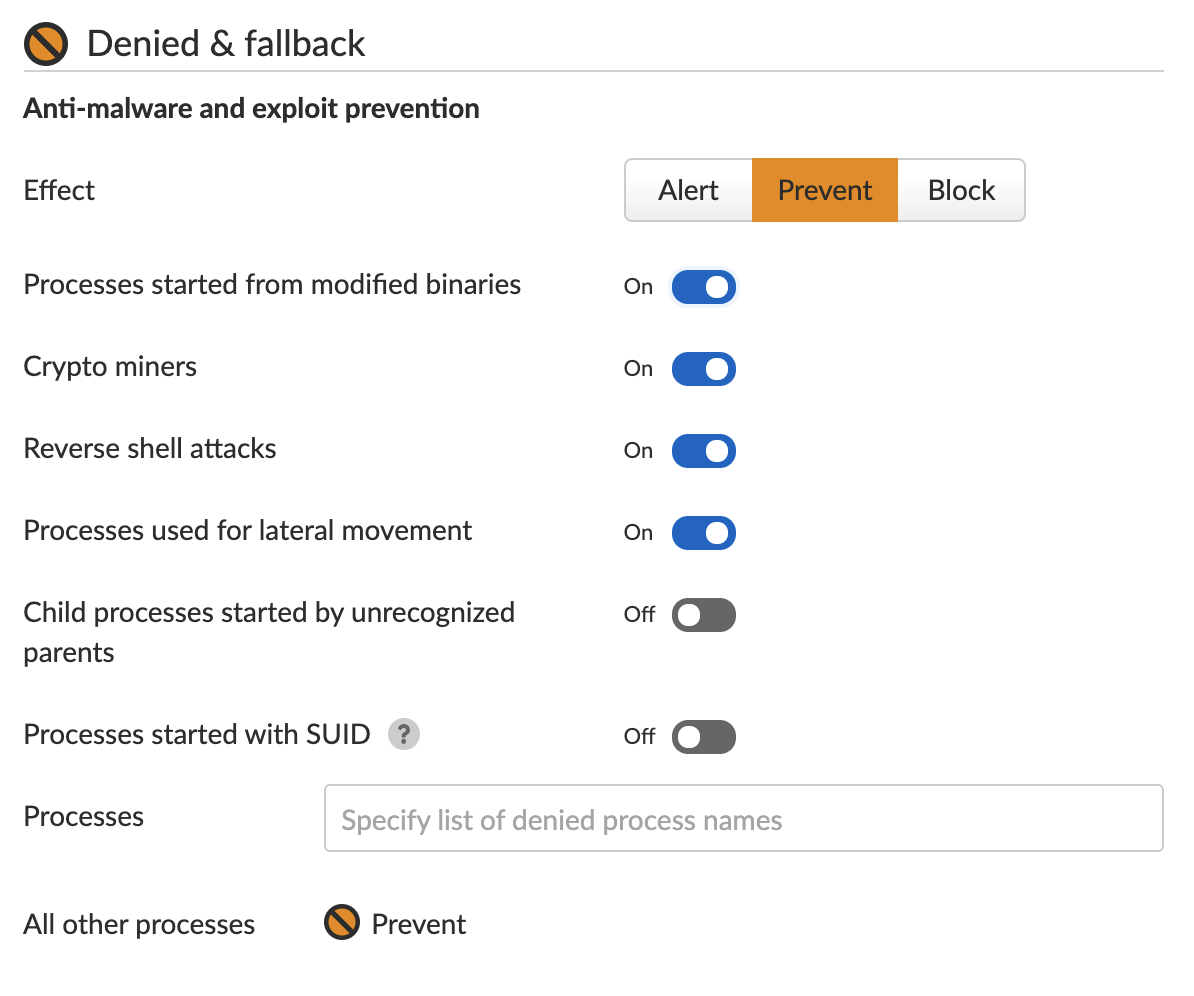

Prisma Cloud’s Runtime Protection feature learns the machine’s behavior and creates a set of rules for processes. Once the learning is complete, the user can choose the action for new, unexpected processes attempting to execute. The user can choose to alert, prevent or completely block the execution.

Indicators of Compromise

| Description | SHA256 |

| Our Siloscape variant | 5B7A23676EE1953247A0364AC431B193E32C952CF17B205D36F800C270753FCB |

| unzip.exe, the unzip binary Siloscape writes to the disk | 81046F943D26501561612A629D8BE95AF254BC161011BA8A62D25C34C16D6D2A |

| tor.zip, the tor archive Silsocape writes to the disk | 010859BA20684AEABA986928A28E1AF219BAEBBF51B273FF47CB382987373DB7 |

Additional Resources

Unit 42 Discovers First Known Malware Targeting Windows Containers

Webinar: Unit 42 researchers will cover the details of Siloscape live.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.