This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

When a host is infected or otherwise compromised, security professionals with access to packet captures (pcaps) of the network traffic need to understand the activity and identify the type of infection.

This tutorial offers tips on how to identify Trickbot, an information stealer and banking malware that has been infecting victims since 2016. Trickbot is distributed through malicious spam (malspam), and it is also distributed by other malware such as Emotet, IcedID, or Ursnif.

Trickbot has distinct traffic patterns. This tutorial reviews pcaps of Trickbot infections caused by two different methods: a Trickbot infection from malspam and Trickbot when it is distributed through other malware.

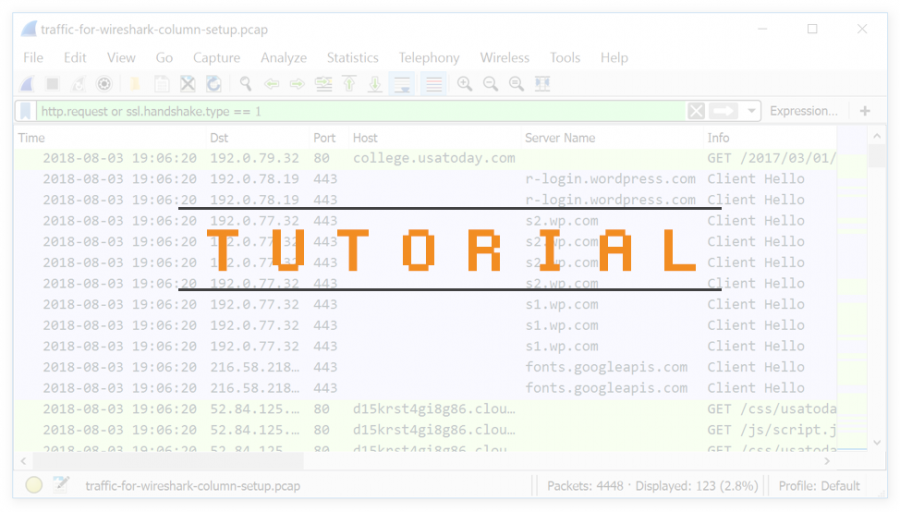

Note: Today’s tutorial requires Wireshark with a column display customized according to this previous tutorial. You should already have implemented Wireshark display filters as described here.

Trickbot from malspam

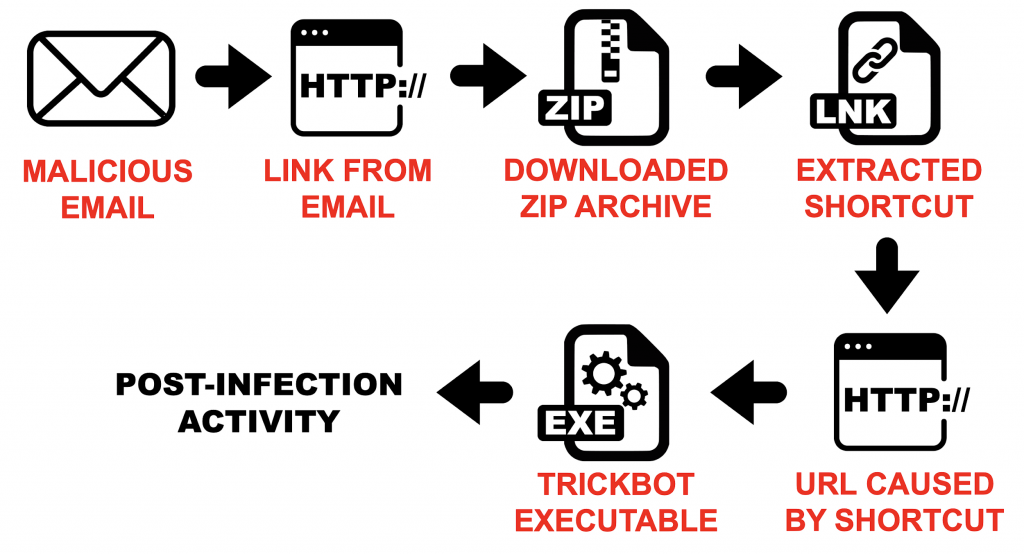

Trickbot is often distributed through malspam. Emails from these campaigns contain links to download malicious files disguised as invoices or documents. These files may be Windows executable files for Trickbot, or they may be some sort of downloader for the Trickbot executable. In some cases, links from these emails return a zip archive that contains a Trickbot executable or downloader.

Figure 1 shows an example from September 2019. In this example, the email contained a link that returned a zip archive. The zip archive contained a Windows shortcut file that downloaded a Trickbot executable. A pcap for the associated Trickbot infection is available here.

Figure 1: Flowchart from a Trickbot infection from malspam in September 2019.

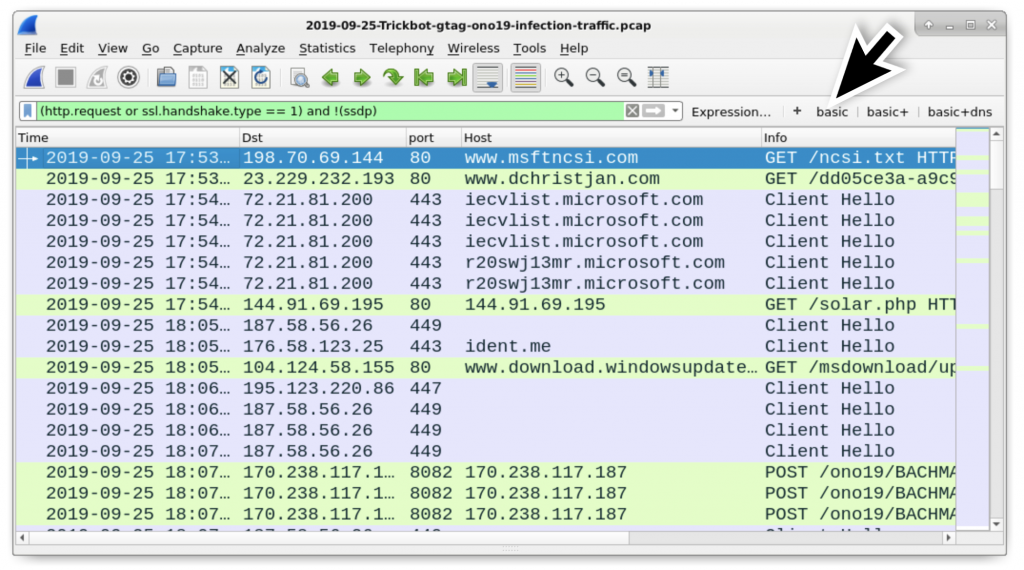

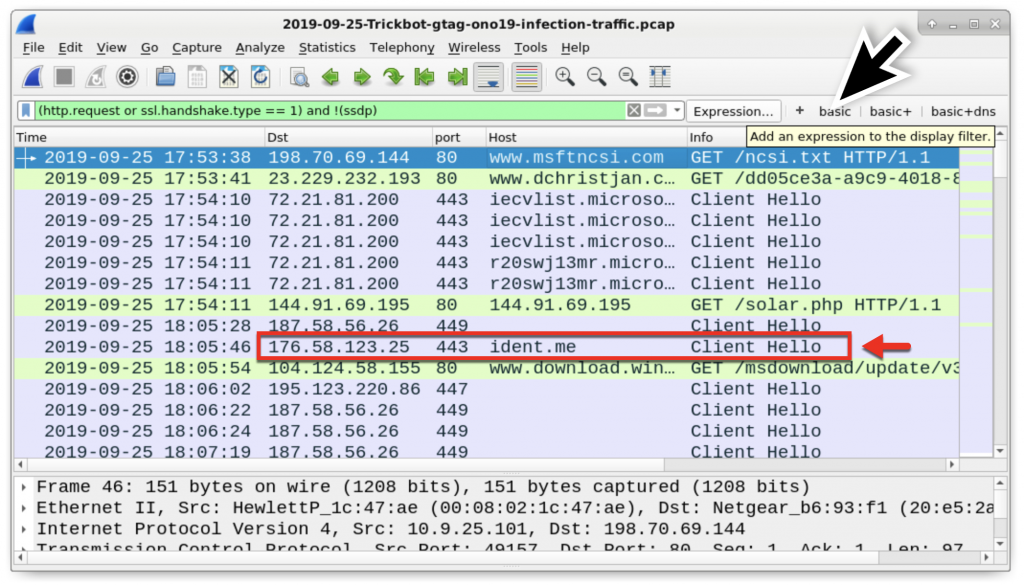

Download the pcap from this page. The pcap is contained in a password-protected zip archive named 2019-09-25-Trickbot-gtag-ono19-infection-traffic.pcap.zip. Extract the pcap from the zip archive using the password infected and open it in Wireshark. Use your basic filter to review the web-based infection traffic as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Pcap of the Trickbot infection viewed in Wireshark.

Figure 2: Pcap of the Trickbot infection viewed in Wireshark.

Review the traffic, and you will find the following activity common in recent Trickbot infections:

- An IP address check by the infected Windows host

- HTTPS/SSL/TLS traffic over TCP ports 447 and 449

- HTTP traffic over TCP port 8082

- HTTP requests ending in .png that return Windows executable files

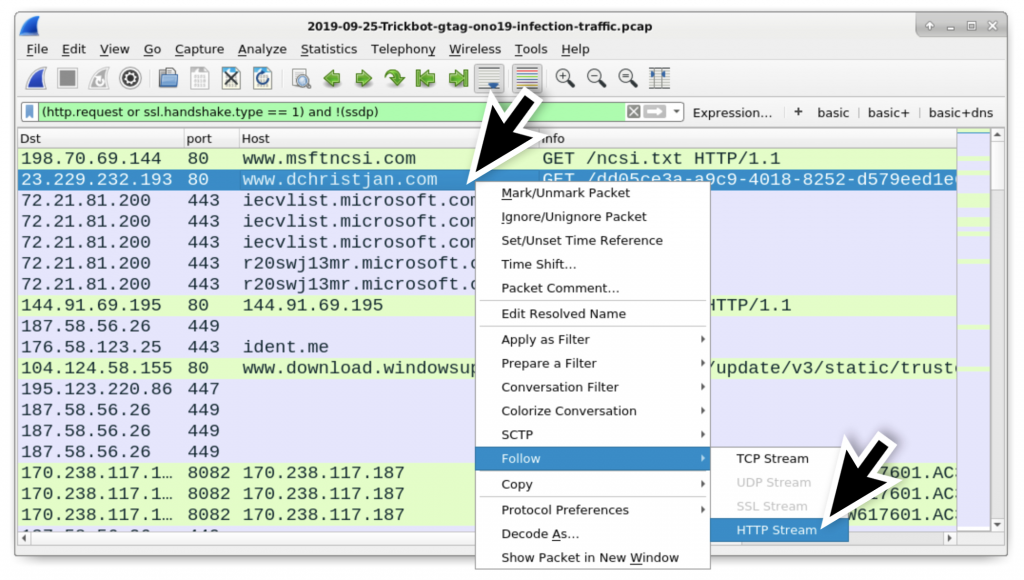

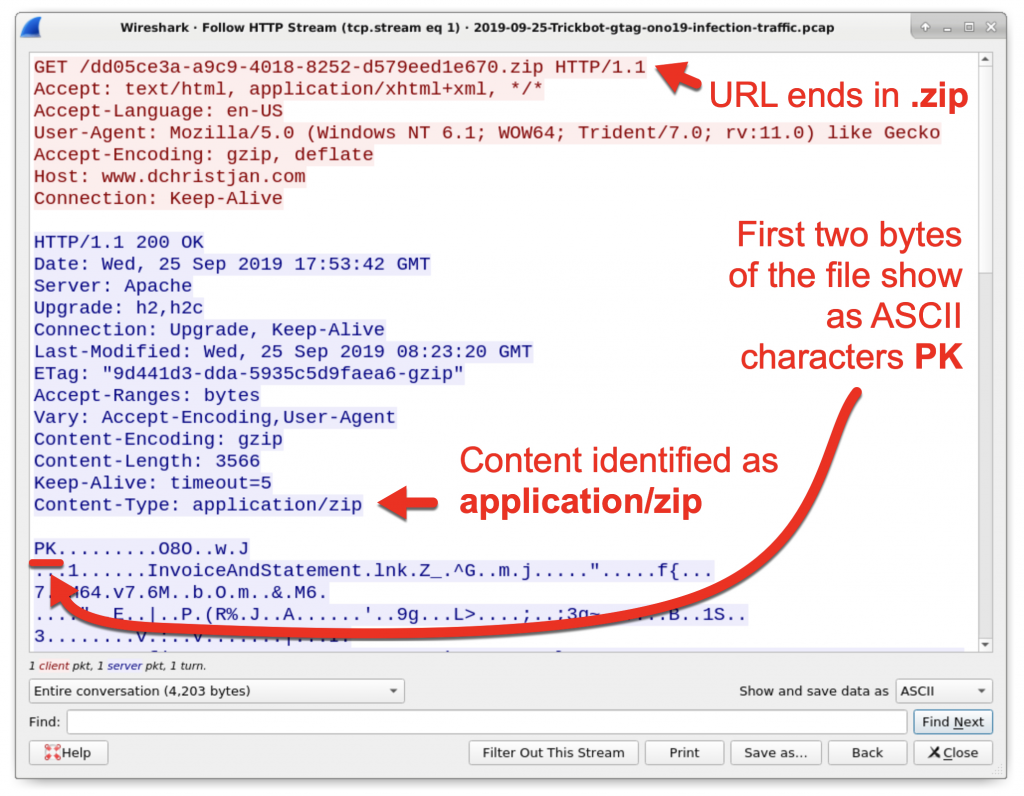

Unique to this Trickbot infection is an HTTP request to www.dchristjan[.]com that returned a zip archive and an HTTP request to 144.91.69[.]195 that returned a Windows executable file. Follow the HTTP stream for the request to www.dchristjan[.]com as shown in Figure 3 to review the traffic. In the HTTP stream, you will find indicators that a zip archive was returned as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3: Following the HTTP stream for the request to www.dchristjan[.]com.

Figure 3: Following the HTTP stream for the request to www.dchristjan[.]com.

Figure 4: Indicators the HTTP request returned a zip archive.

Figure 4: Indicators the HTTP request returned a zip archive.

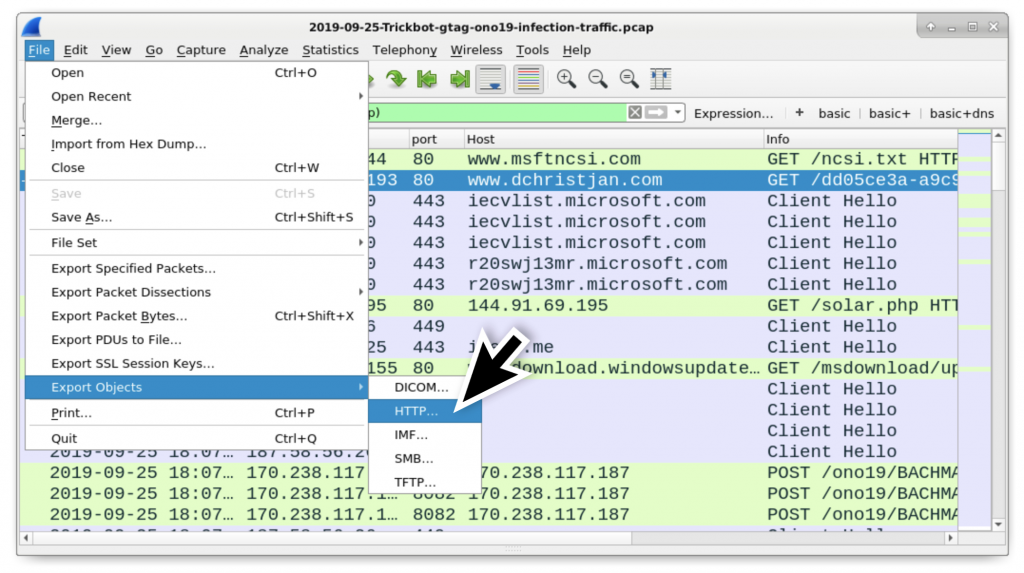

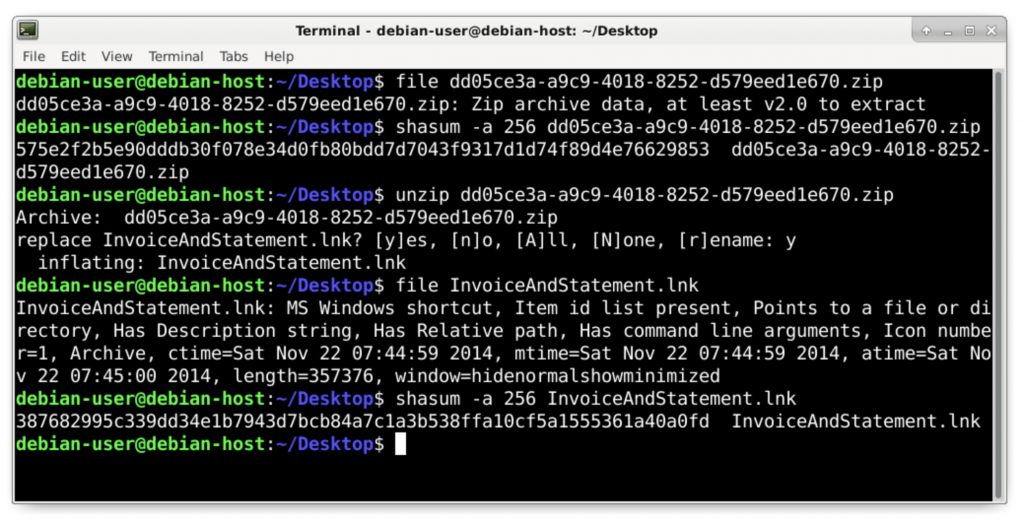

In Figure 4, you can also see the name of the file contained in the zip archive, InvoiceAndStatement.lnk. You can export the zip archive from the traffic using Wireshark as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6 using the following path:

File → Export Objects → HTTP…

Figure 5: Exporting HTTP objects from the pcap.

Figure 5: Exporting HTTP objects from the pcap.

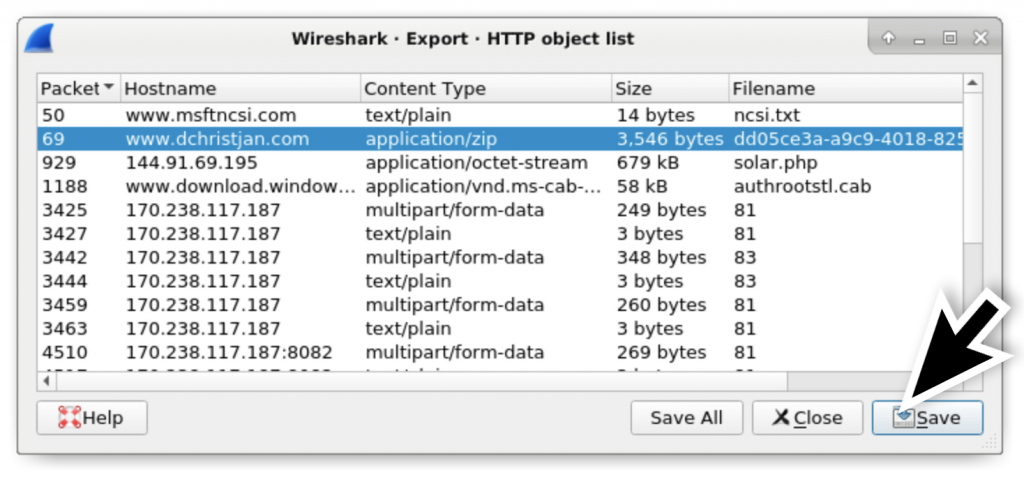

Figure 6: Exporting the zip archive from the pcap.

In a BSD, Linux, or Mac environment, you can easily confirm the extracted file is a zip archive, get the SHA256 hash of the file, and extract the contents of the archive in a command line environment. In this case, the content is a Windows shortcut file, which you can also confirm and get the SHA256 hash as shown in Figure 7.

The command to identify the file type is file [filename], while the command to find the SHA256 hash of the file is shasum -a 256 [filename].

Figure 7: Checking the extracted zip archive and its contents.

Figure 7: Checking the extracted zip archive and its contents.

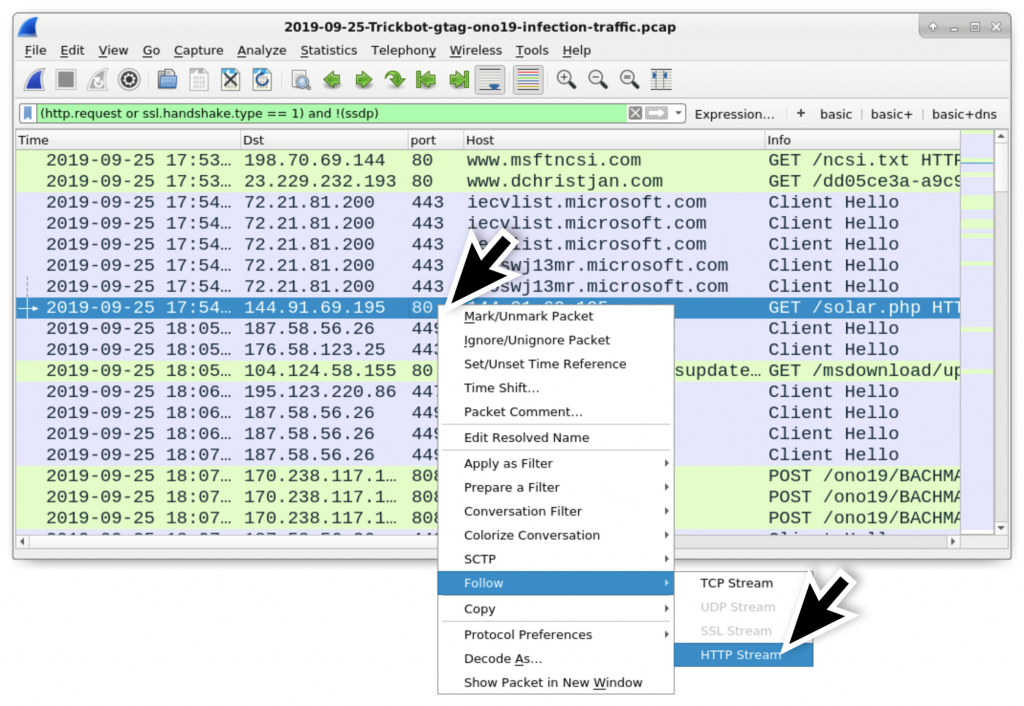

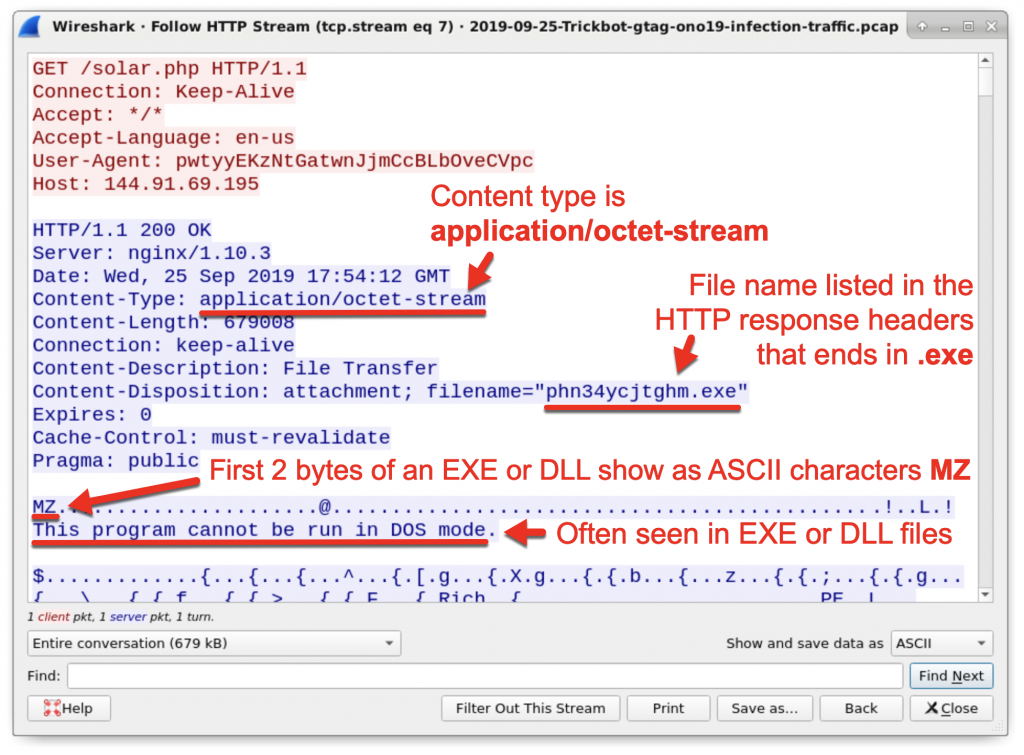

An HTTP request to 144.91.69[.]195 returned a Windows executable file. This is the initial Windows executable for Trickbot. You can follow the HTTP stream for this HTTP request and find indicators this is an executable file as shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9. You can extract the executable file from the pcap as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 8: Following the HTTP stream for the HTTP request to 144.91.69[.]195.

Figure 8: Following the HTTP stream for the HTTP request to 144.91.69[.]195.

Figure 9: Indicators the returned file is a Windows executable or DLL file.

Figure 9: Indicators the returned file is a Windows executable or DLL file.

Figure 10: Exporting the Windows executable from the pcap.

Figure 10: Exporting the Windows executable from the pcap.

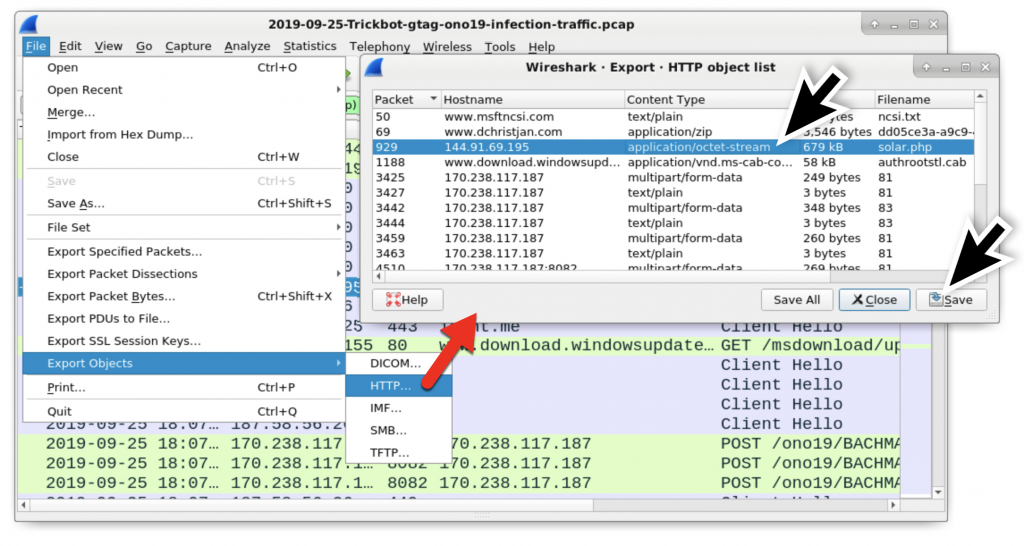

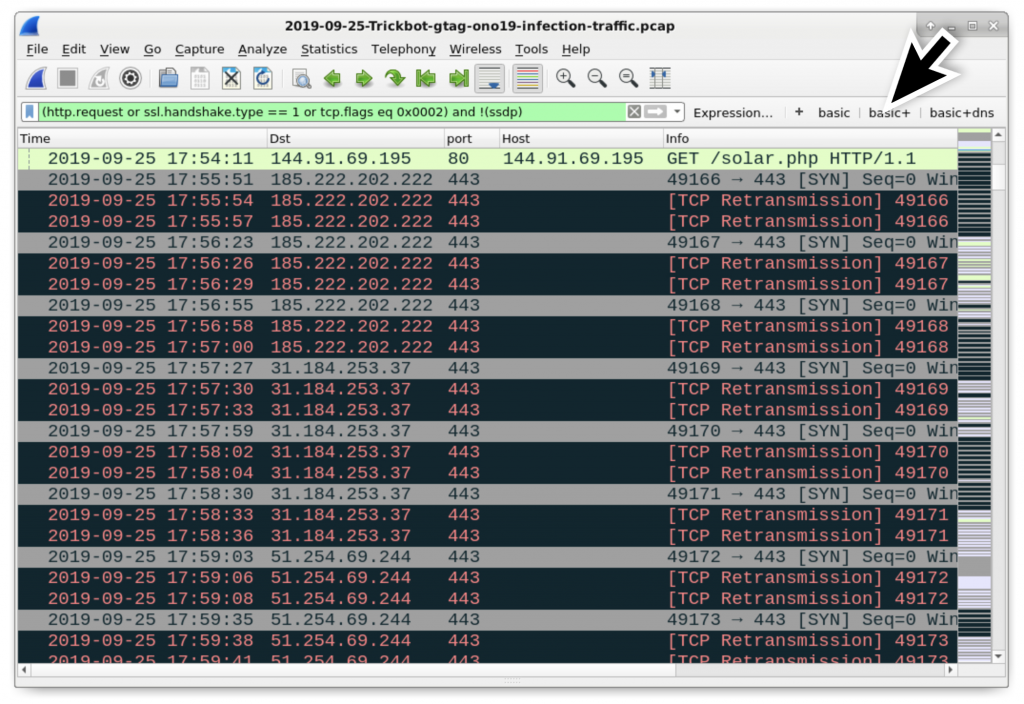

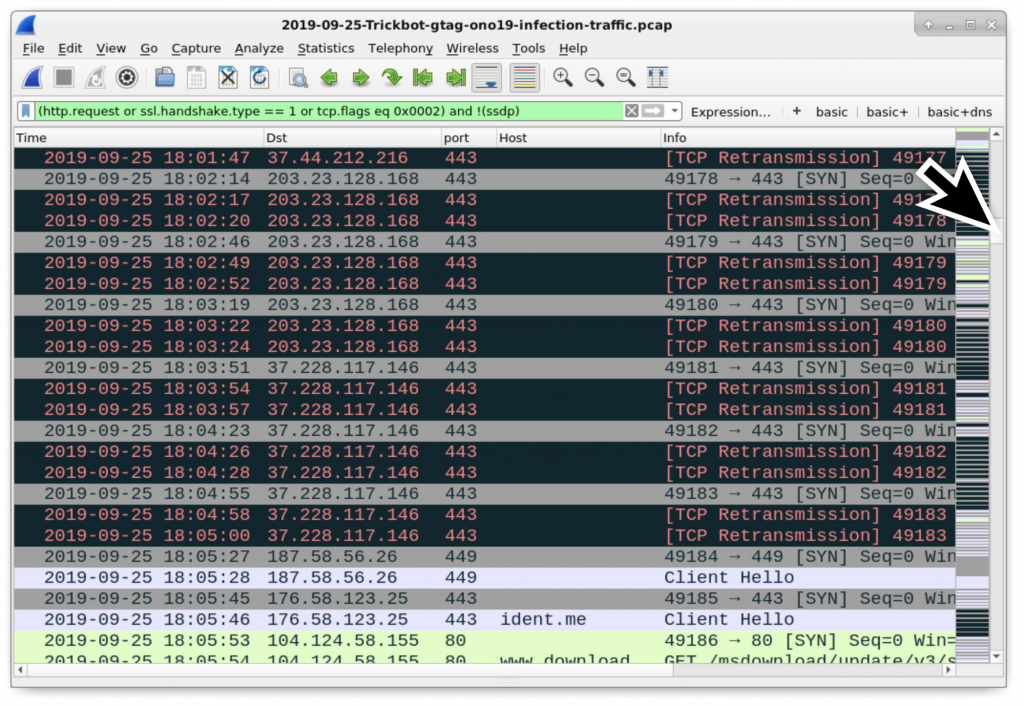

Post infection traffic initially consists of HTTPS/SSL/TLS traffic over TCP port 443, 447, or 449 and an IP address check by the infected Windows host. In this infection, shortly after the HTTP request for the Trickbot executable, we can see several attempted TCP connections over port 443 to different IP addresses before the successful TCP connection to 187.58.56[.]26 over TCP port 449. If you use your basic+ filter, you can see these attempted connections as shown in Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Figure 11: Attempted TCP connections over port 443 by the infected Windows host.

Figure 11: Attempted TCP connections over port 443 by the infected Windows host.

Figure 12: Scrolling down to see more TCP connections over port 443 before a successful connection to 187.58.56[.]26 over TCP port 449.

Figure 12: Scrolling down to see more TCP connections over port 443 before a successful connection to 187.58.56[.]26 over TCP port 449.

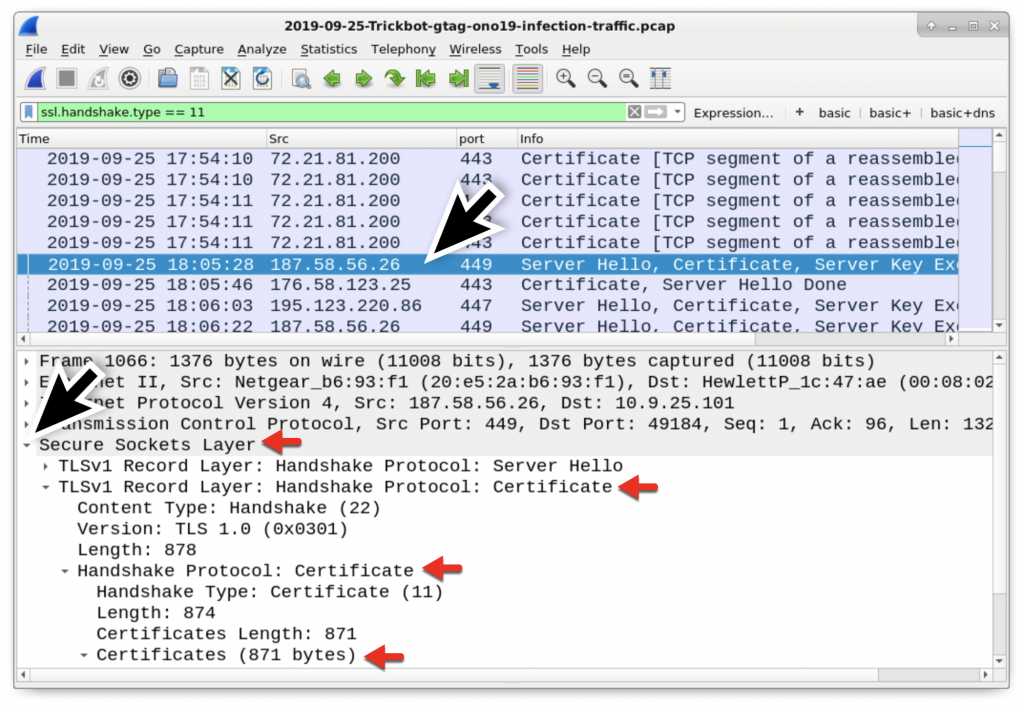

The HTTPS/SSL/TLS traffic to various IP addresses over TCP port 447 and TCP port 449 has unusual certificate data. We can review the certificate issuer by filtering on ssl.handshake.type == 11 when using Wireshark 2.x or tls.handshake.type == 11 when using Wireshark 3.x. Then go to the frame details section and expand the information, finding your way to the certificate issuer data as seen in Figure 13 and Figure 14.

Figure 13: Filtering for the certificate data in the HTTPS/SSL/TLS traffic, then expanding lines the frame details for the first result under TCP port 449.

Figure 13: Filtering for the certificate data in the HTTPS/SSL/TLS traffic, then expanding lines the frame details for the first result under TCP port 449.

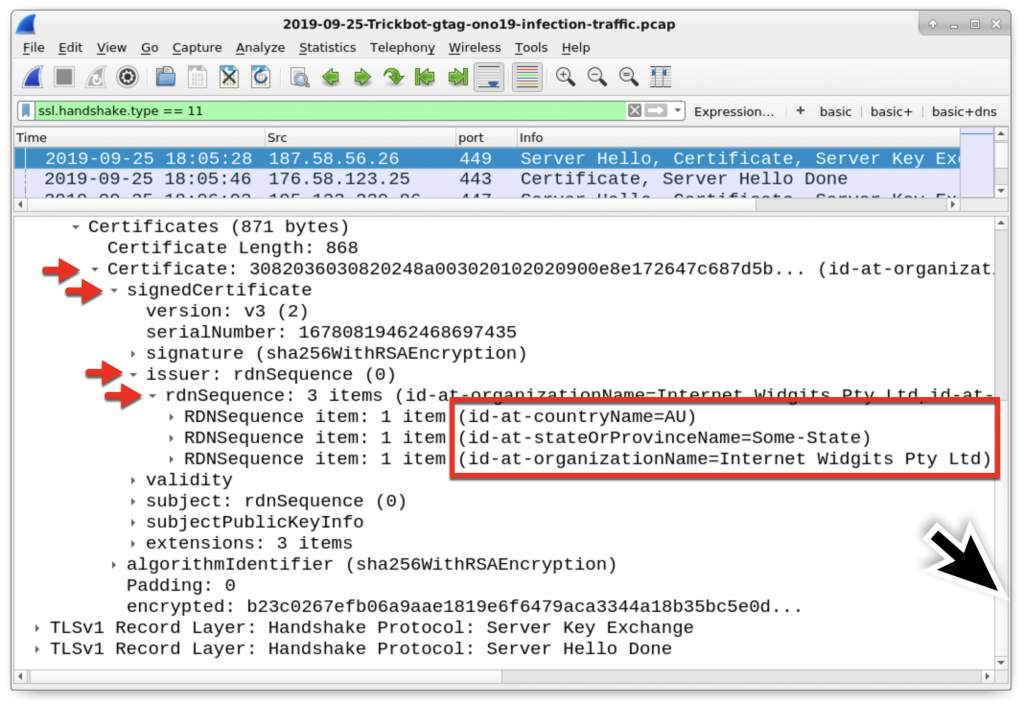

Figure 14: Drilling down to the certificate issuer data on the first result over TCP port 449.

Figure 14: Drilling down to the certificate issuer data on the first result over TCP port 449.

In Figure 14, we see the following certificate issuer data used in HTTPS/SSL/TLS traffic to 187.58.56[.]26 over TCP port 449:

- id-at-countryName=AU

- id-at-stateOrProvinceName=Some-State

- id-at-organizationName=Internet Widgits Pty Ltd

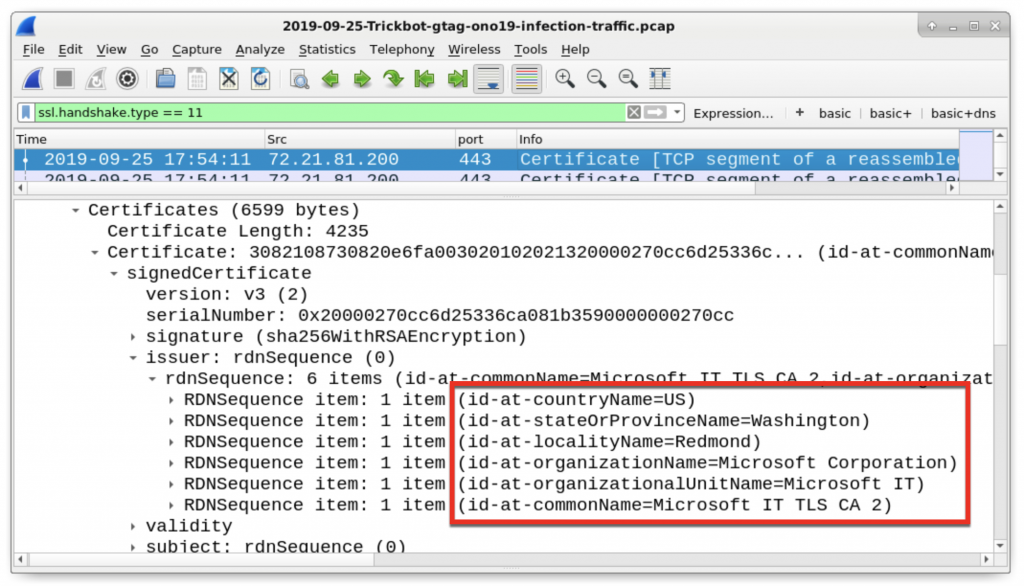

The state or province name (Some-State) and the organization name (Internet Widgits Pty Ltd) are not used for legitimate HTTPS/SSL/TLS traffic. This is an indicator of malicious traffic, and this type of unusual certificate issuer data is not limited to Trickbot. What does a normal certificate issuer look like in legitimate HTTPS/SSL/TLS traffic? If we look at earlier traffic to Microsoft domains at 72.21.81.200 over TCP port 443, we find the following as seen in Figure 15.

- id-at-countryName=US

- id-at-stateOrProvinceName=Washington

- id-at-localityName=Redmond

- id-at-organizationName=Microsoft Corporation

- id-at-organizationUnitName=Microsoft IT

- id-at-commonName=Microsoft IT TLS CA 2

Figure 15: Certificate data from legitimate HTTPS traffic to a Microsoft domain.

Figure 15: Certificate data from legitimate HTTPS traffic to a Microsoft domain.

The Trickbot-infected Windows host will check its IP address using a number of different IP address checking sites. These sites are not malicious, and the traffic is not inherently malicious. However, this type of IP address check is common with Trickbot and other families of malware. Various legitimate IP address checking services used by Trickbot include:

- api.ip[.]sb

- checkip.amazonaws[.]com

- icanhazip[.]com

- ident[.]me

- ip.anysrc[.]net

- ipecho[.]net

- ipinfo[.]io

- myexternalip[.]com

- wtfismyip[.]com

Again, an IP address check by itself is not malicious. However, this type of activity combined with other network traffic can provide indicators of an infection, like we see in this case.

Figure 16: IP address check by the infected Windows host, right after HTTPS/SSL/TLS traffic over TCP port 449. Not inherently malicious, but this is part of a Trickbot infection.

Figure 16: IP address check by the infected Windows host, right after HTTPS/SSL/TLS traffic over TCP port 449. Not inherently malicious, but this is part of a Trickbot infection.

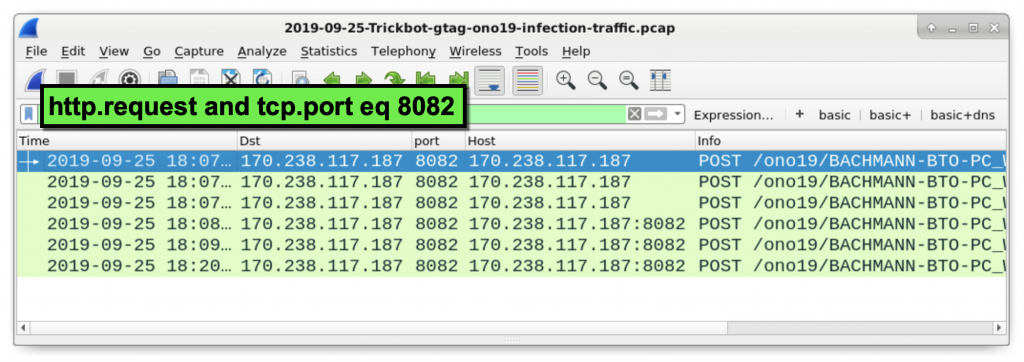

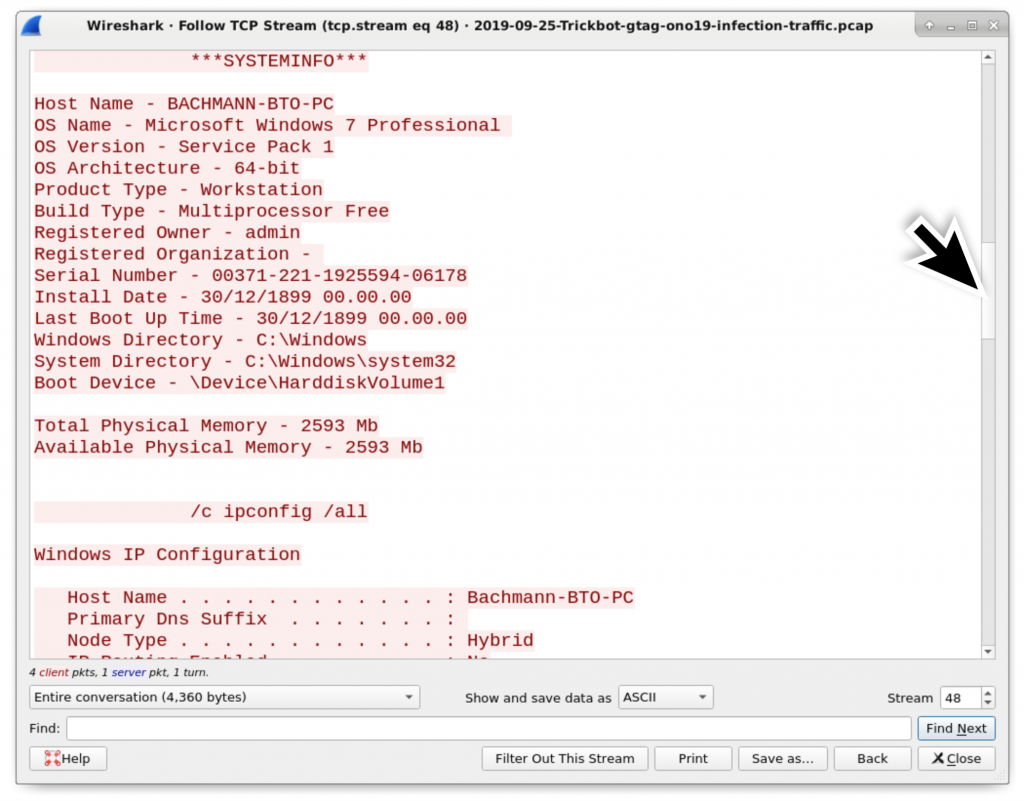

A Trickbot infection currently generates HTTP traffic over TCP port 8082 this traffic sends information from the infected host like system information and passwords from the browser cache and email clients. This information is sent from the infected host to command and control servers used by Trickbot.

To review this traffic, use the following Wireshark filter:

http.request and tcp.port eq 8082

This reveals the following HTTP requests as seen in Figure 17:

- 170.238.117[.]187 port 8082 - 170.238.117[.]187 - POST

/ono19/BACHMANN-BTO-PC_W617601.AC3B679F4A22738281E6D7B0C5946

E42/81/ - 170.238.117[.]187 port 8082 - 170.238.117[.]187 - POST

/ono19/BACHMANN-BTO-PC_W617601.AC3B679F4A22738281E6D7B0C5946

E42/83/ - 170.238.117[.]187 port 8082 - 170.238.117[.]187 - POST

/ono19/BACHMANN-BTO-PC_W617601.AC3B679F4A22738281E6D7B0C5946

E42/81/ - 170.238.117[.]187 port 8082 - 170.238.117[.]187:8082 - POST

/ono19/BACHMANN-BTO-PC_W617601.AC3B679F4A22738281E6D7B0C5946

E42/81/ - 170.238.117[.]187 port 8082 - 170.238.117[.]187:8082 - POST

/ono19/BACHMANN-BTO-PC_W617601.AC3B679F4A22738281E6D7B0C5946

E42/90 - 170.238.117[.]187 port 8082 - 170.238.117[.]187:8082 - POST

/ono19/BACHMANN-BTO-PC_W617601.AC3B679F4A22738281E6D7B0C5946

E42/90

Figure 17: HTTP traffic over TCP port 8082 caused by Trickbot.

Figure 17: HTTP traffic over TCP port 8082 caused by Trickbot.

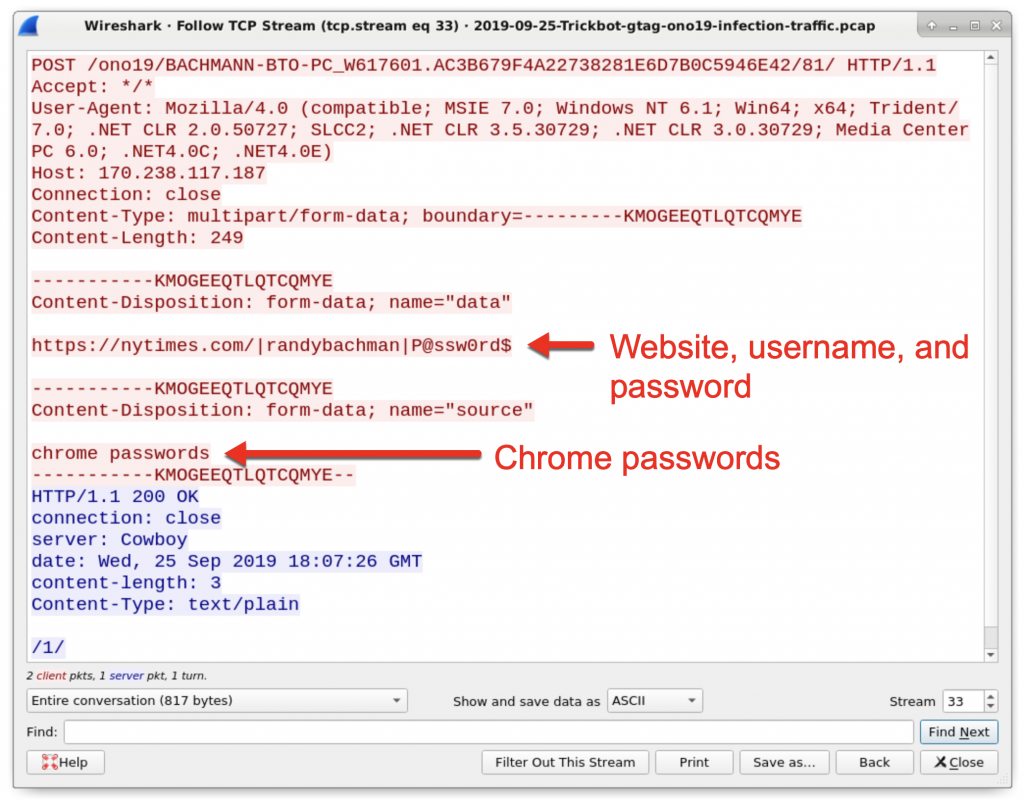

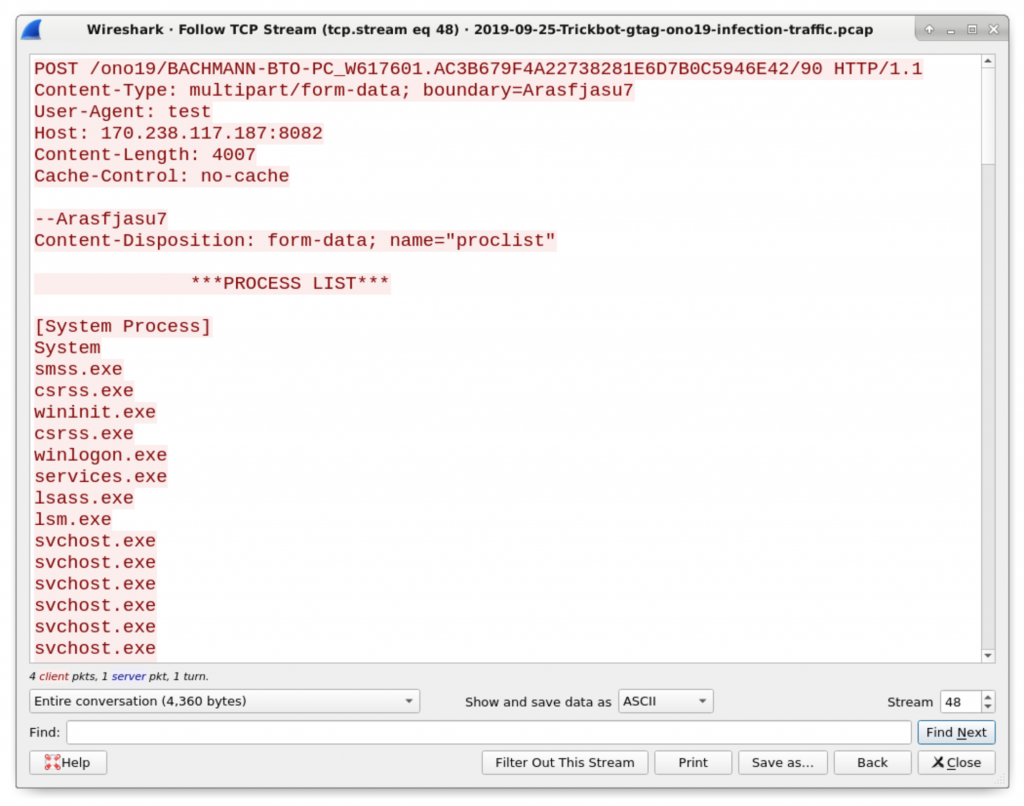

HTTP POST requests ending in 81 send cached password data from web browsers, email clients, and other applications. HTTP POST requests ending in 83 send form data submitted by applications like web browsers. We can find system information sent through HTTP POST requests ending in 90. Follow the TCP or HTTP streams for any of these HTTP POST requests to review data stolen by this infection.

Figure 18: Login credentials stolen by Trickbot from the Chrome web browser. This data was sent by the Trickbot-infected host using HTTP traffic over TCP port 8082.

Figure 18: Login credentials stolen by Trickbot from the Chrome web browser. This data was sent by the Trickbot-infected host using HTTP traffic over TCP port 8082.

Figure 19: System data sent by a Trickbot-infected host using HTTP traffic over TCP port 8082. It starts with a list of running processes.

Figure 19: System data sent by a Trickbot-infected host using HTTP traffic over TCP port 8082. It starts with a list of running processes.

Figure 20: More system data sent by a Trickbot-infected host using HTTP traffic over TCP port 8082. This is later from the same HTTP stream that started in Figure 19.

Figure 20: More system data sent by a Trickbot-infected host using HTTP traffic over TCP port 8082. This is later from the same HTTP stream that started in Figure 19.

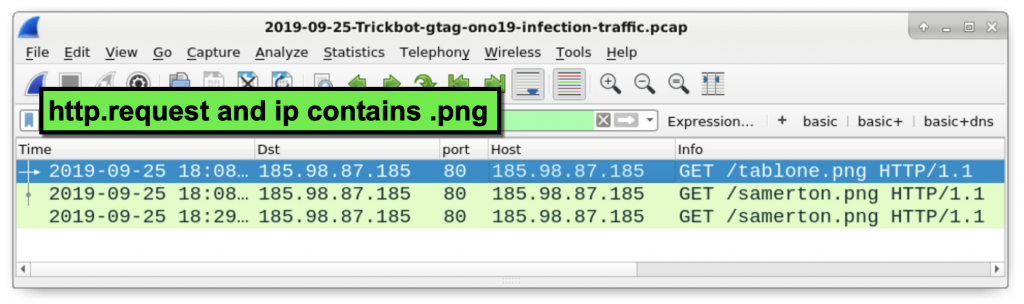

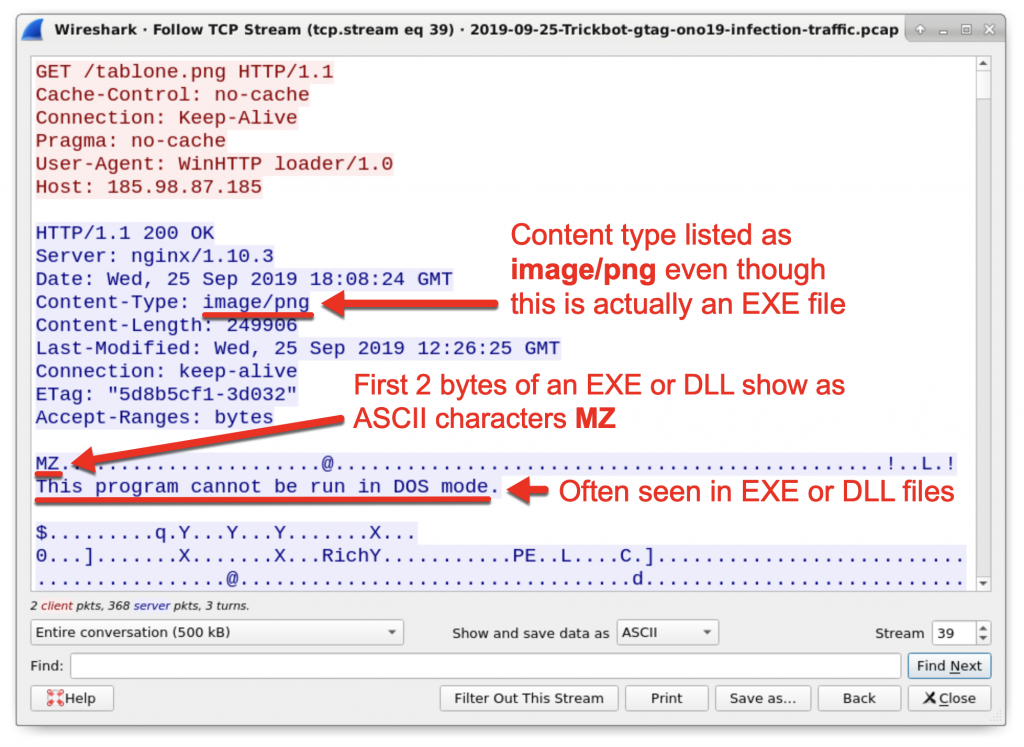

Trickbot sends more Windows executable files over HTTP GET requests ending in .png. These follow-up Trickbot executables are used to infect a vulnerable domain controller (DC) when the infected Windows host is a client in an Active Directory environment.

You can find these URLs in the pcap by using the following Wireshark filter:

http.request and ip contains .png

Figure 21: Filtering to find follow-up Trickbot EXE files sent using URLs ending with .png.

Figure 21: Filtering to find follow-up Trickbot EXE files sent using URLs ending with .png.

Follow the TCP or HTTP stream in each of the three requests as shown in Figure 21. You should see indicators of windows executable files similar to what we saw in Figure 9. However, in this case, the HTTP response headers identify the returned file as image/png even though it clearly is a Windows executable or DLL file.

Figure 22: Windows executable sent through URL ending in .png.

Figure 22: Windows executable sent through URL ending in .png.

You can export these files from Wireshark, confirm they are Windows executable files, and get the SHA256 file hashes as we covered earlier in this tutorial.

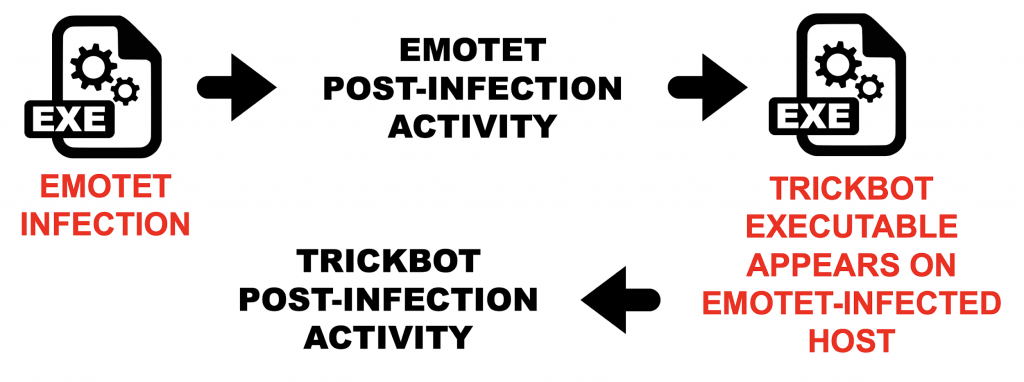

Trickbot Distributed Through Other Malware

Trickbot is frequently distributed through other malware. Trickbot is commonly seen as follow-up malware to Emotet infections, but we have also seen it as follow-up malware from IcedID and Ursnif infections

Since Emotet frequently distributes Trickbot, lets review an Emotet with Trickbot infection in September 2019 documented here. We already covered Emotet with Trickbot infections last year in this Palo Alto Networks blog post, so this tutorial will focus on the Trickbot activity.

Figure 23: Simplified flow chart for Emotet with Trickbot activity.

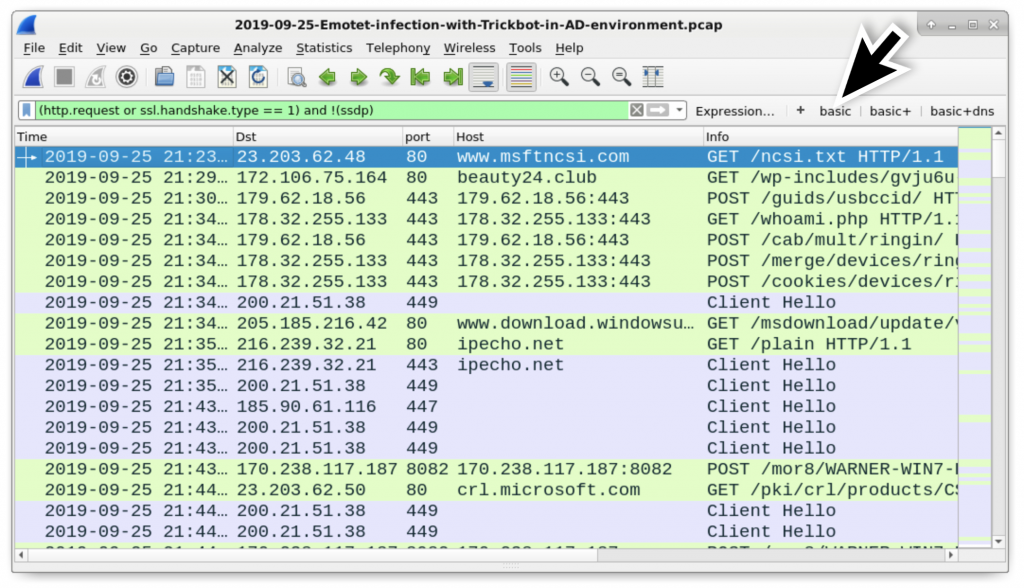

Download the pcap from this page. The pcap is contained in a password-protected zip archive named 2019-09-25-Emotet-infection-with-Trickbot-in-AD-environment.pcap.zip. Extract the pcap from the zip archive using the password infected and open it in Wireshark. Use your basic filter to review the web-based infection traffic as shown in Figure 24.

Figure 24: Filtering on web traffic in an Emotet+Trickbot infection.

Figure 24: Filtering on web traffic in an Emotet+Trickbot infection.

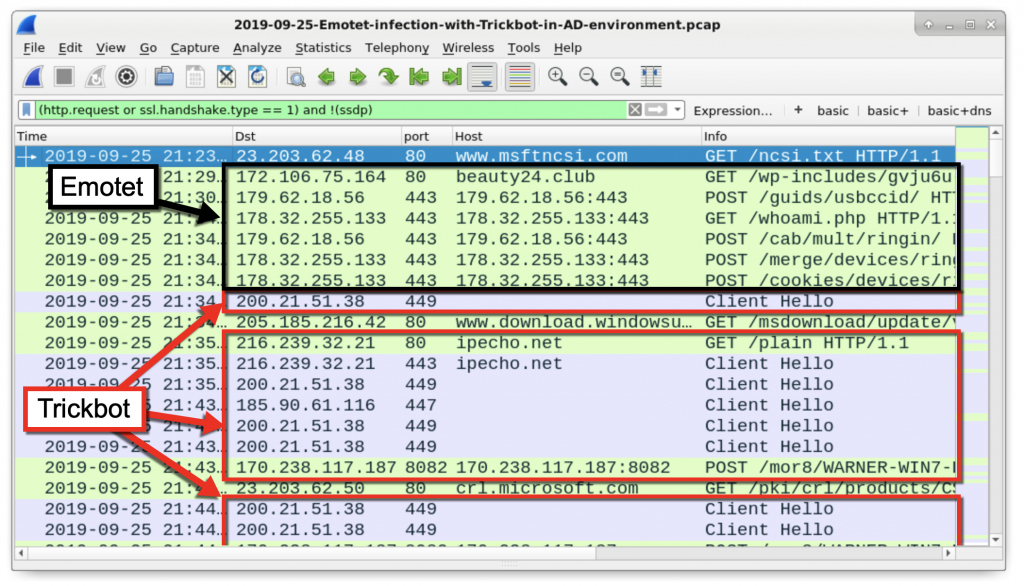

Experienced analysts can usually identify the Emotet-generated traffic and the Trickbot-generated traffic. Post-infection Emotet activity consists HTTP traffic with encoded data returned by the server. This is distinctly different than post-infection Trickbot activity which generally relies on HTTPS/SSL/TLS traffic for command and control communications. Figure 25 points out the different infection traffic between Emotet and Trickbot for this specific infection.

Figure 25: The differences in Emotet and Trickbot traffic.

Figure 25: The differences in Emotet and Trickbot traffic.

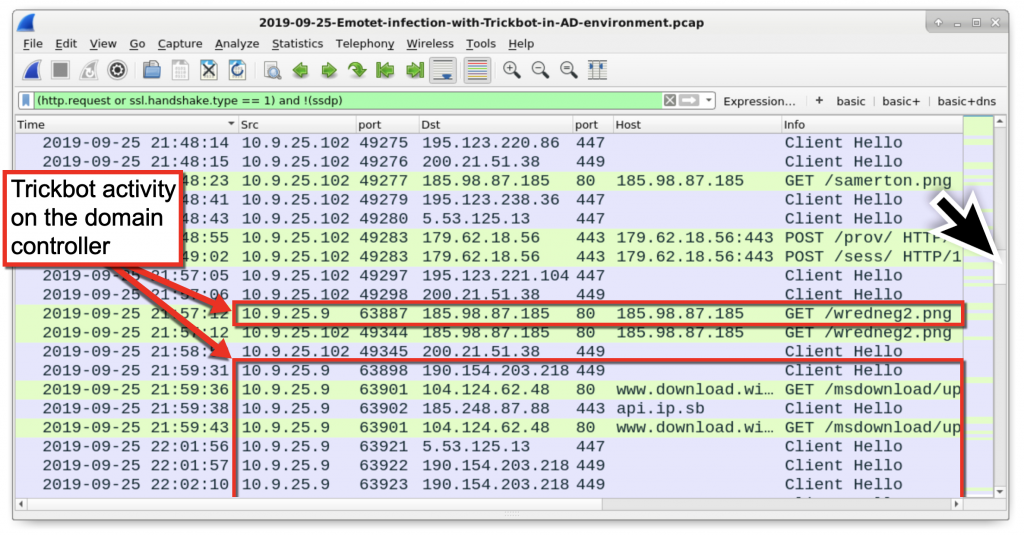

This infection happened in an Active Directory environment with 10.9.25.102 as the infected Windows client and 10.9.25.9 as the DC. Later in the traffic, we see the DC exhibit signs of Trickbot infection as shown in Figure 26.

Figure 26: Trickbot activity on the DC.

Figure 26: Trickbot activity on the DC.

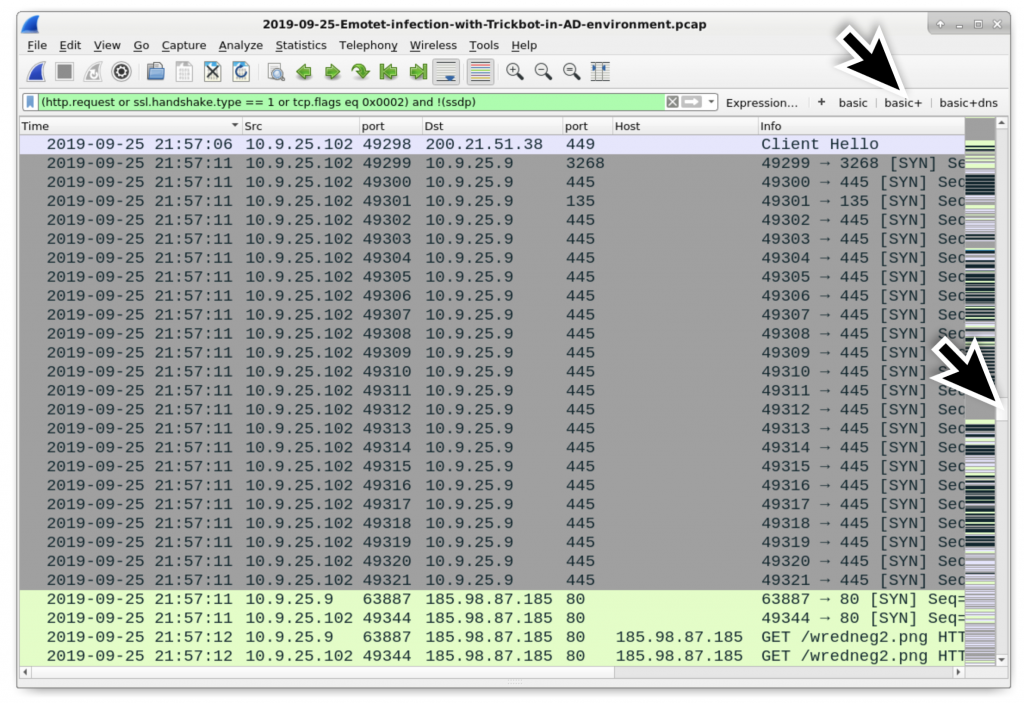

How did the infection move from client to DC? Trickbot uses a version of the EternalBlue exploit to move laterally using Microsoft’s SMB protocol. In this case, the infected Windows client sent information several times over TCP port 445 to the DC at 10.9.25.9, which then retrieved a Trickbot executable from 185.98.87[.]185/wredneg2.png. Use the basic+ filter to see the SYN segments for the traffic between the client at 10.9.25.102 and the DC at 10.9.25.9 right before the DC calls out to 185.98.87[.]185 as shown in Figure 27

Figure 27: Finding traffic from the client at 10.9.25.102) to the DC at 10.9.25.9 (shown in grey) before the DC retrieved a Trickbot EXE from 196.98.87[.]185/wredneg2.png.

Figure 27: Finding traffic from the client at 10.9.25.102) to the DC at 10.9.25.9 (shown in grey) before the DC retrieved a Trickbot EXE from 196.98.87[.]185/wredneg2.png.

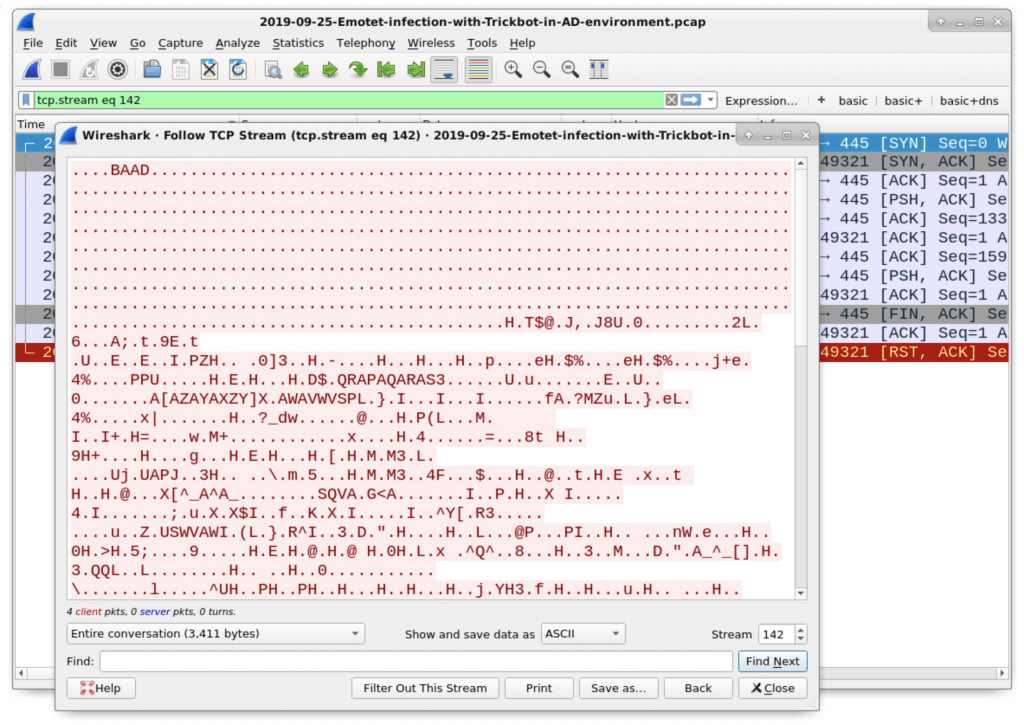

Follow one of the TCP streams, for example the line with a source as 10.9.25.102 over TCP port 49321 and destination as 10.9.35.9 over TCP port 445. This is highly unusual traffic for a client to send to a DC, so it is likely related to the EternalBlue exploit. See Figure 28 for an example of this traffic

Figure 28: Example of the unusual traffic from a client to DC over TCP port 445, possibly related to an EternalBlue-based exploit.

Figure 28: Example of the unusual traffic from a client to DC over TCP port 445, possibly related to an EternalBlue-based exploit.

Other than this unusual SMB traffic and the DC getting infected, any Trickbot-specific activity in this pcap is remarkably similar to our previous example.

Conclusion

This tutorial provided tips for examining Windows infections with Trickbot malware by reviewing two pcaps from September 2019. More pcaps with recent examples of Trickbot activity can be found at malware-traffic-analysis.net.

For more help with Wireshark, see our previous tutorials:

- Customizing Wireshark - Changing Your Column Display

- Using Wireshark - Display Filter Expressions

- Using Wireshark: Identifying Hosts and Users

- Using Wireshark: Exporting Objects from a Pcap

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.