Executive Summary

This article explores the misuse of QR codes in today's threat landscape, covering three areas of concern:

- QR codes using URL shorteners to disguise malicious destinations

- QR codes using in-app deep links to steal account credentials and take control of a victim's apps

- QR codes attempting to bypass app store security by linking to direct downloads of malicious apps

With QR codes a notable presence in our everyday lives, some people instinctively scan them without hesitation. But QR codes are also a vector for attack. QR codes enable attackers to bypass organizational security by exploiting the weaker controls of personal mobile devices. By doing this, they can trick users into scanning codes and interacting with malicious destinations outside the corporate security perimeter.

Over the past several months, we have tracked campaigns that used QR codes for phishing (known as quishing) and scams. Our telemetry reveals an average of over 11,000 detections of malicious QR codes each day. Investigating these detections, we found that attackers are leveraging QR code shorteners, in-app deep links and direct downloads to bypass people’s awareness and security controls.

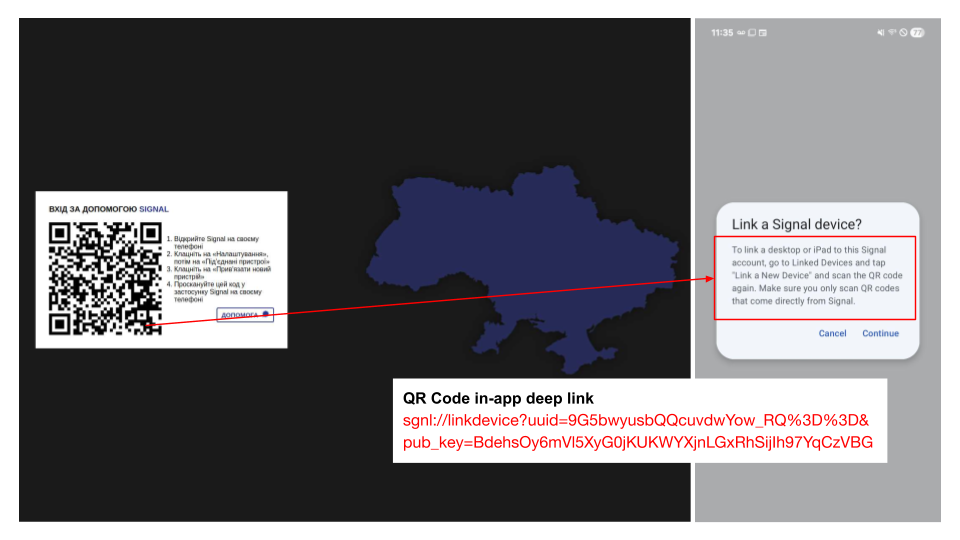

In addition to mass campaigns, we see attackers using QR codes for highly targeted messenger app phishing, such as targeting Ukrainian Signal users in the context of the Russia-Ukraine war. These findings necessitate further analysis of deep links and QR code data.

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from the threats described in this article through the following products and services:

If you think you might have been compromised or have an urgent matter, contact the Unit 42 Incident Response team.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | QR Codes, Phishing, Social Engineering |

Phishing QR Codes Not New, but a Growing Threat

QR codes are not a new technology, but their prevalence has increased with the push for contactless interactions, especially during the initial emergency phase of the coronavirus pandemic. QR codes allow companies to interact seamlessly with their customer base for payments, enabling customers to join rewards programs and sign up for apps or mailing services. People have grown used to QR codes in daily life, and often scan them without sufficient caution, increasing their susceptibility to attacks.

The popularity of QR codes has led to their use by attackers. In our offline web crawlers, we currently find an average of 75,000 detections of QR codes each day, with 15% of these pages containing QR codes leading to malicious links. This represents an average of over 11,000 detections of malicious QR code use each day.

Problem of Evasive QR Code Redirects

We looked beyond the recognized risks of QR codes. While straightforward QR code web-based attacks remain a threat, our focus shifted to understanding how attackers are leveraging the following trends to remain evasive to both victims and security controls:

- QR code shorteners

- In-app deep links (special URLs that allow people to open specific content within a mobile app)

- Direct app file downloads

These tactics represent an evolution in QR code-based attacks that security teams need to address.

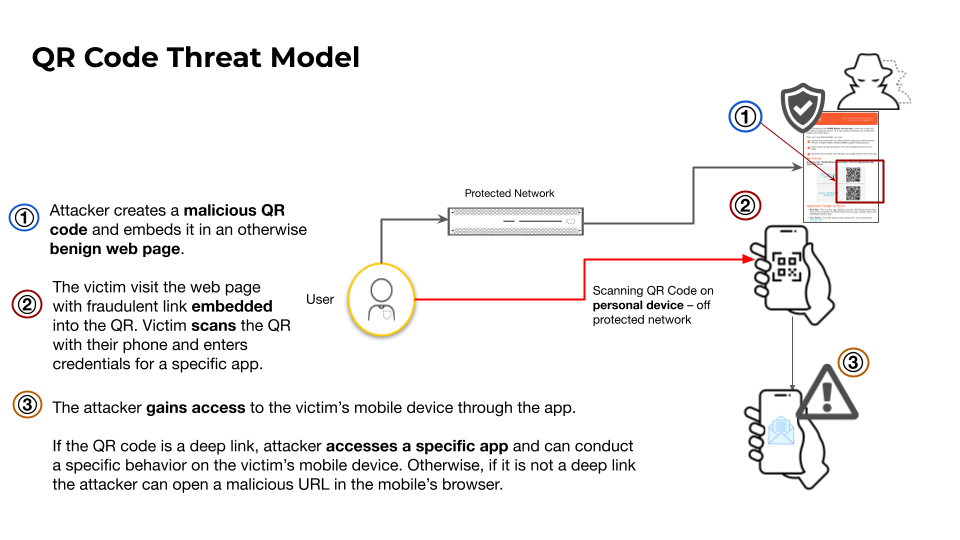

Previous Unit 42 research has covered several key attack vectors for phishing QR codes hosted on documents, which are also relevant when hosted on websites. Attacks through these vectors can be effective for several reasons including:

- Lower user vigilance

- Security solutions having difficulty extracting URLs embedded in QR codes

- Complex redirection chains that obscure final destinations

- Weaker security controls on personal mobile devices

- Hosting on otherwise legitimate-looking pages

Building upon this threat model, in-app deep links allow the attacker to target specific apps and trigger specific behavior (Figure 1).

QR codes on websites need to be analyzed by security crawlers and other security solutions. To close this security gap, specific QR code detection techniques must be deployed to analyze the various data types stored in QR codes:

- Standard HTTPS URLs

- Deep links

- Non-URL content (e.g., JSON, plaintext)

Key Definitions

QR code shorteners are services that combine a URL shortener with a QR code generator to create a shorter, more scannable QR code that links to a long URL. These shorteners offer benefits such as reducing the size of the QR code, allowing attackers to change the destination URL later, and tracking scan data in a single dashboard.

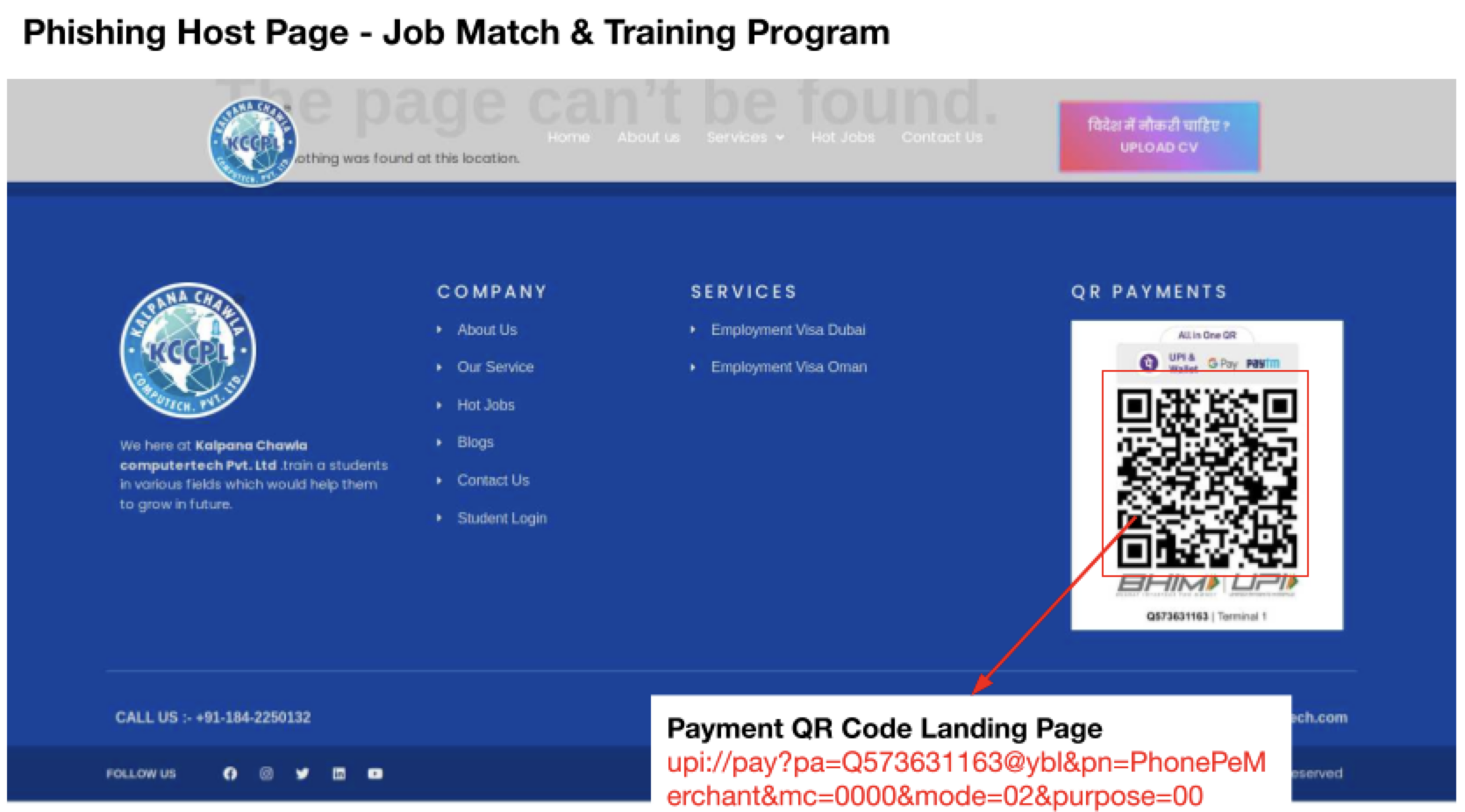

In-app deep links are hyperlinks that direct visitors to a specific screen or content within a mobile app. In-app deep links can use both custom URL schemes (i.e., sms:+1234567890:Hello, tg[:]//login?token= ) or standard web URLs (i.e., hxxps[:]//wa[.]me/settings/linked_devices#) that the operating system redirects to the app.

Figure 2 shows an example that displays a phishing site impersonating a job match and training program website that hosts a payment in-app deep link. Deep links are often used to improve user experience by reducing the number of steps to access specific content from external sources like emails, social media, authentication tokens or ads.

The Stealth Factor: QR Code Shorteners

Attackers use QR code shorteners to mask malicious destinations. QR code shorteners convert a static image into a dynamic endpoint. Consequently, the attacker can change the redirect destination at will.

The attacker is also able to leverage the good reputation of QR code shortener services to evade detection of malicious activity. Even security-conscious people who check the URL preview before scanning cannot determine the final destination when presented with shortened links. This technique effectively prevents targets from being aware of potential threats until after the malicious payload has been delivered.

Our previous article has already talked about the risk of URL shorteners more broadly. However, the combination of a QR code and URL shortener is even more likely to bypass scrutiny.

Steady Increase in QR Code Shortener Traffic

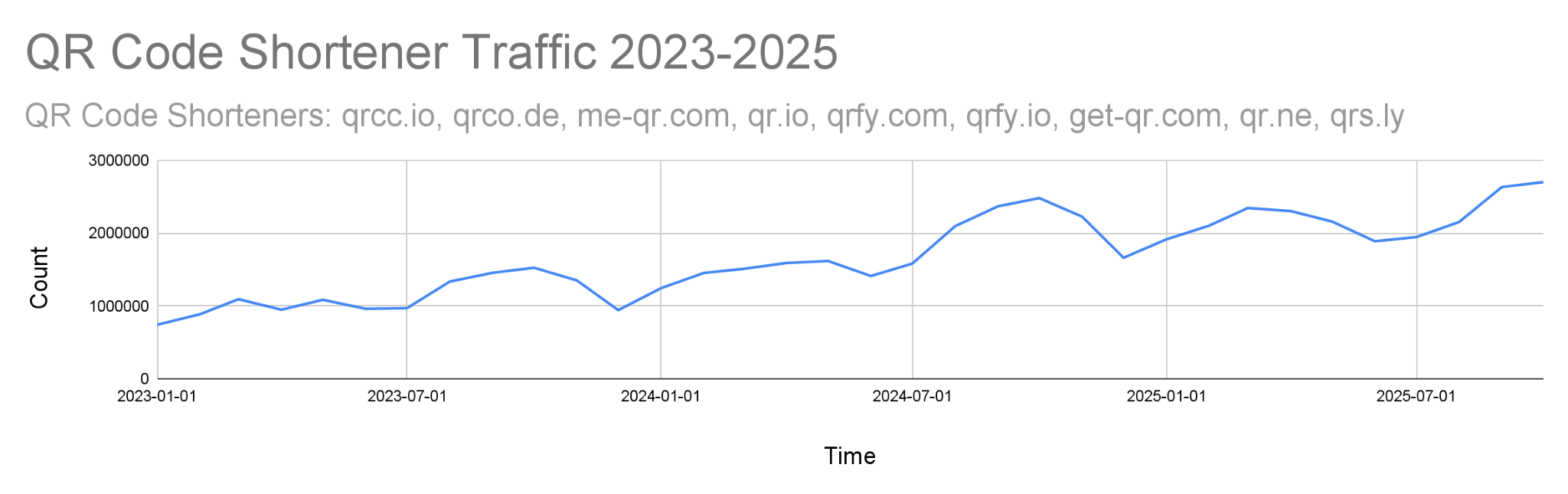

We have seen QR code shortener traffic grow steadily over the past three years (Figure 3).

We see a steady increase of QR code shortener traffic in our telemetry. This includes a 55% increase from the first half of 2023 to the first half of 2024 and a 44% increase from the first half of 2024 to the first half of 2025. This data is based on the following popular QR code shortener services:

- qrcc[.]io

- qrco[.]de

- me-qr[.]com

- qr[.]io

- qrfy[.]com

- qrfy[.]io

- get-qr[.]com

- qr[.]ne, qrs[.]ly

Most Misused QR Code Shortener Services

Our telemetry reveals that qrco[.]de, me-qr[.]com and qrs[.]ly are the most used QR code shorteners. Compared to the top QR code shorteners mentioned in the Anti-Phishing Working Group (APWG) phishing trends report [PDF], qrs[.]ly is a notable new addition as the QR code shortener used in 7.3% of the malicious URLs observed.

Targeted Industries

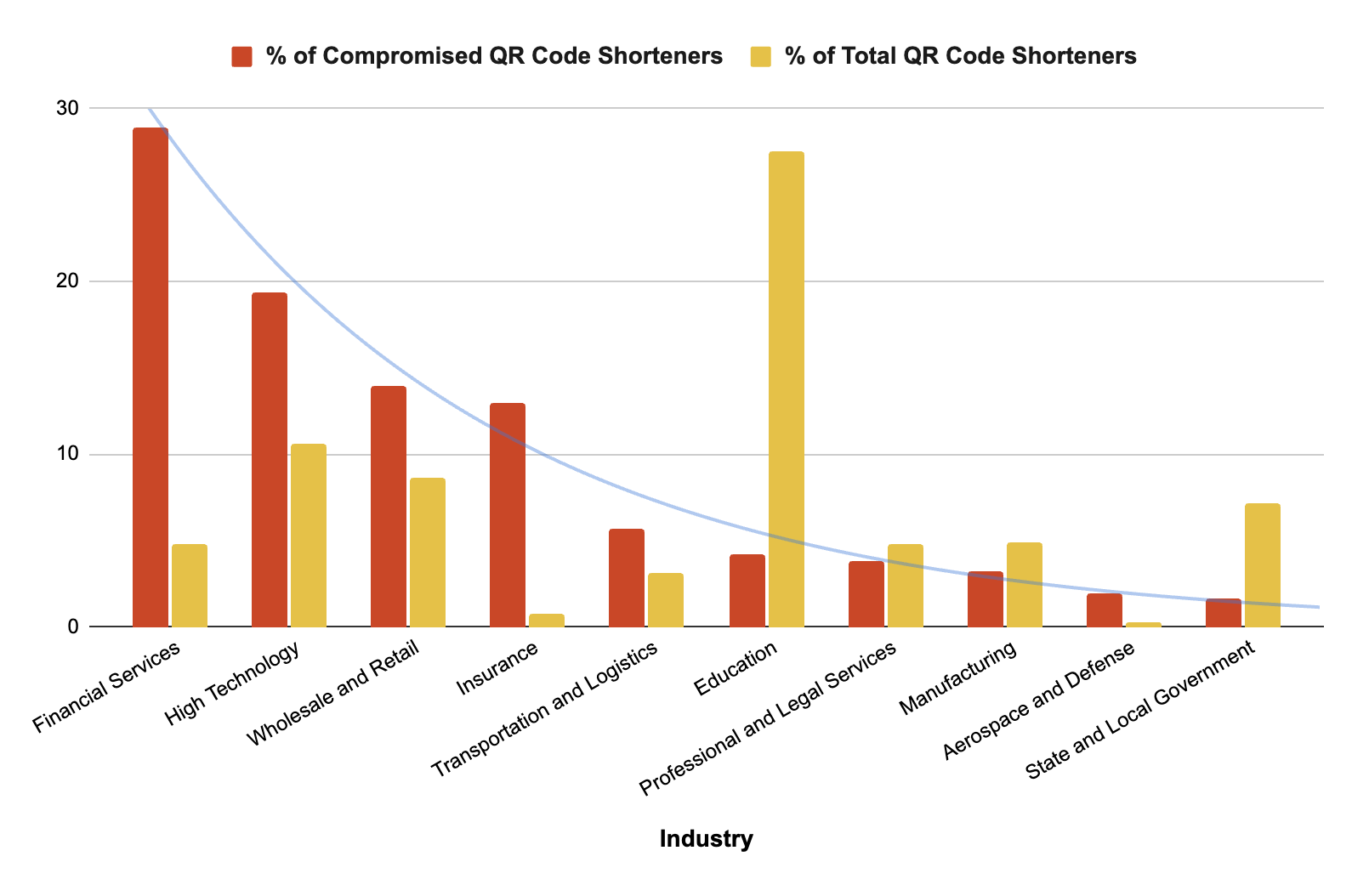

Financial services was the most impacted industry when considering compromised QR code shorteners, accounting for 29% of this type of attack. This is followed by high tech (19%) and wholesale and retail (14%). Significantly, QR code shorteners for financial services make up only 4.8% of this type of traffic as a whole. This makes the high percentage of compromised QR code shorteners for financial services even more striking as shown in Figure 4

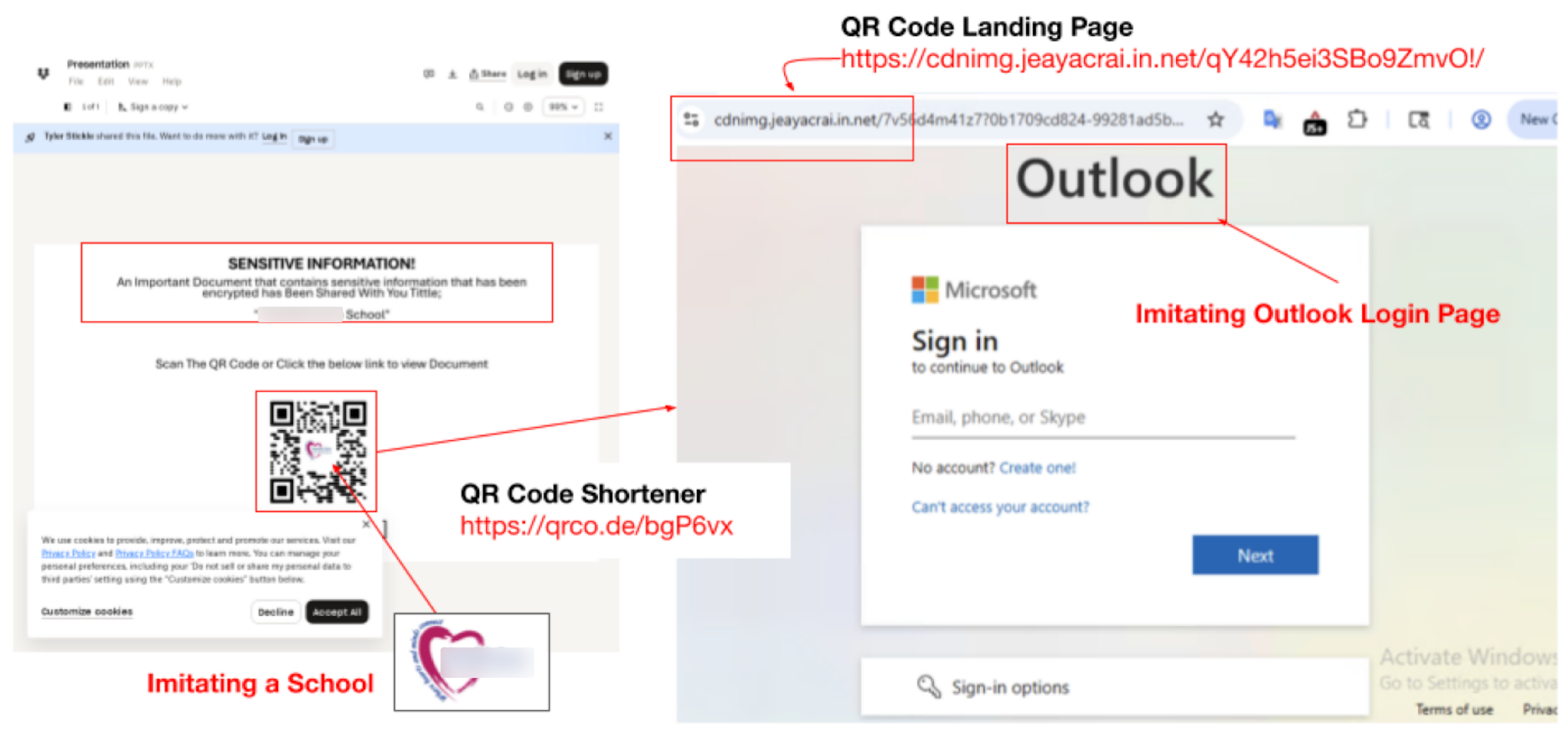

Example of a Phishing Attack Misusing a QR Code Shortener

The webpage shown in Figure 5 is a popular file-sharing platform containing a QR code that appears to imitate a school by including its logo. Upon analysis, we found that it is a QR code shortener that first redirects to a CAPTCHA page and then lands on a phishing page that impersonates Outlook hosted on cdnimg.jeayacrai[.]in[.]net. After a few days, the URL from this QR code no longer worked, illustrating how QR code shorteners are often ephemeral and can quickly cease redirecting to the original malicious endpoint.

In-App Deep Links Vulnerabilities: More Than Just Web Browsing

Modern mobile devices support a wide range of QR code actions beyond simple web browsing. The distribution of in-app deep links in QR codes is an understudied area despite its exploitability. In-app deep links account for about three percent of the QR codes in our telemetry. Attackers can either misuse app functionality (e.g., adding a trusted device, or sending a payment), or push malicious content to those apps (such as, adding malicious links to calendar invites).

Defenders face a challenge in detecting malicious in-app deep links embedded in QR codes because the activity generated by these links is often invisible to standard web crawlers. Effective detection necessitates a mobile sandbox environment with the specific app installed to properly observe and analyze this activity. Custom in-app deep links lack standardization across applications. This makes identifying malicious signals difficult to generalize, often requiring individualized investigation for each case.

Both iOS and Android devices can process QR codes with in-app deep links that have direct app integration. We categorize in-app deep links as those that apply to the following types of apps:

- Social media and communications

- App stores

- Payment

- System utilities (e.g., Wi-Fi, contacts, calendar, telephone, email, SMS, navigation)

The three most popular custom app URLs that we found were for Telegram, XHS Discover (RedNote) and Line, which respectively account for 44.7%, 1.8% and 0.8% of in-app deep links. As we discuss later, attackers commonly misuse Telegram and Line.

Attack Scenarios

In-app deep links enable additional cross-device interactions, creating new attack scenarios via QR codes.

Table 1 lists some examples of the attack chain scenarios possible through in-app deep links.

| Attack Name | Deep Link Category | Description | Example (QR Code Content) |

| Financial fraud | Payment | Direct access to payment applications with pre-filled recipient information | bitcoin:attackers_address |

| Account Takeover | Social Media and Communications | Directs the victim to authenticate the attacker into the victim’s account | Attacker’s website hosts: tg[:]//login?token=xxxx |

| Embedding Malicious URLs | Communications, Other Apps | Attackers can embed malicious URLs in emails or text messages to be sent from the victim’s device, saved into a file, etc. | mailto[:]receive@mail[.]com?subject=Request%5D&body=Please%20visit%20this%20website%20www.malicious-url[.]com

{info-here : www.malicious-url[.]com} |

| Calendar poisoning | System utilities | Malicious meeting links added to calendars that redirect victims to phishing sites when they attempt to join meetings,

Malicious files added to a calendar invite |

BEGIN:VCALENDAR VERSION:2.0 BEGIN:VEVENT SUMMARY:Team Lunch & Planning Session DTSTART:20251205T120000 DTEND:20251205T130000 LOCATION: www.phishing-meeting-link-url[.]com

DESCRIPTION:Discuss Q4 results and plan for Q1 goals. END:VEVENT END:VCALENDAR |

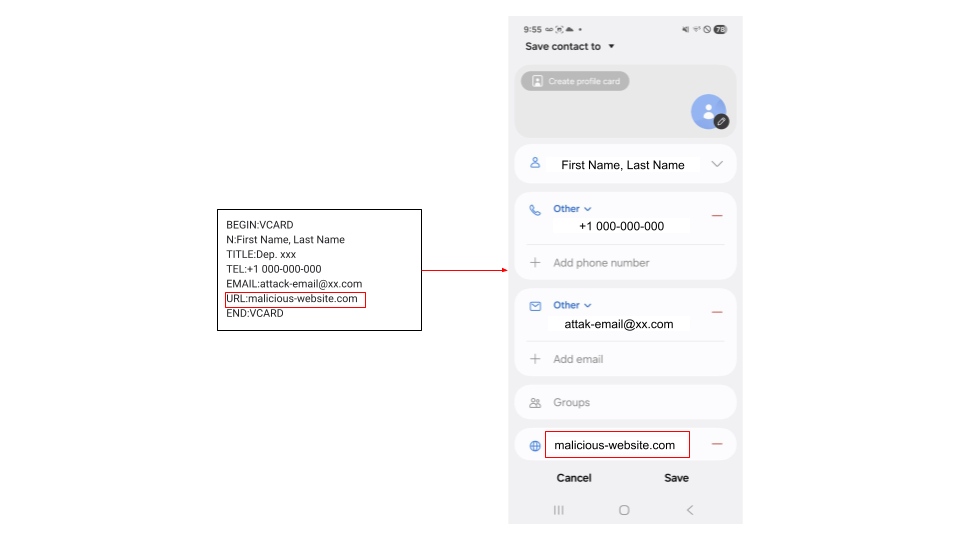

| Contact poisoning | System utilities | Embedding malicious URLs or fake contacts within contact information that activate when victims interact with saved contacts | BEGIN:VCARD

N:First Name, Last Name TITLE:Dep. xxx TEL:+1 000-000-000 EMAIL:attack-email@xx[.]com URL:malicious-website[.]com END:VCARD |

| Rogue Wifi networks | System utilities | Automatically connecting victims to attacker-controlled networks | WIFI:T:WPA;S:attacker-network-name;P:password;H:false; |

Table 1. Attack scenarios involving in-app deep links.

Many of these attack scenarios involve embedding malicious URLs into specific data entries stored in mobile apps. Figure 6 illustrates this for contact poisoning, where a malicious URL is embedded in a saved contact card.

Some of the scenarios described in Table 1 were not observed in our data collection, while others were. The ones not observed are plausible, but hypothetical scenarios. We will further discuss the scenarios observed in our data collection below.

Current Attack Trends and Examples

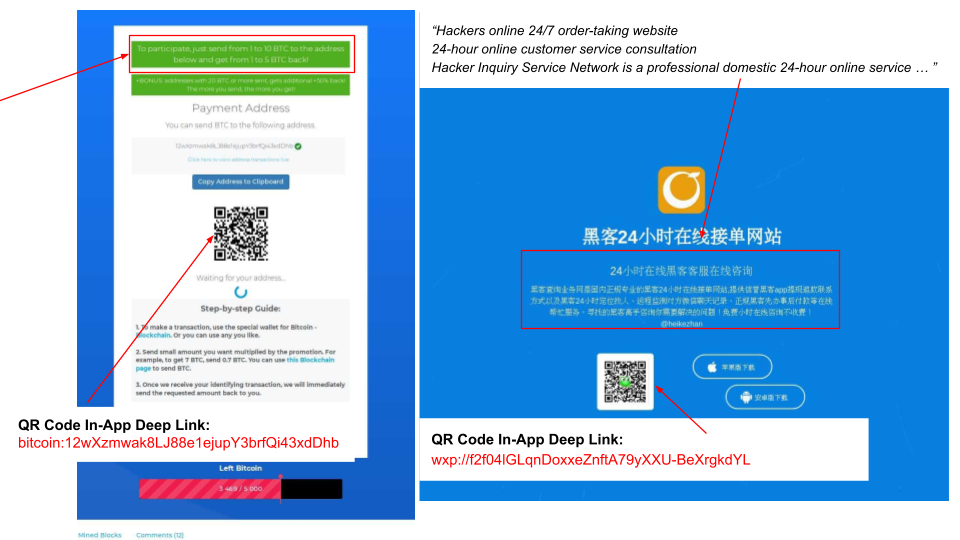

Financial Fraud In-App Deep Links

Financial in-app deep links represent a significant financial risk to potential victims. QR codes are commonly used in legitimate business transactions to facilitate payments, making it straightforward for attackers to misuse this trusted interaction through phishing schemes. We observed legitimate in-app deep links from popular payment apps such as:

- WeChat Pay

- Alipay

- Bitcoin

- Ethereum

- LitCoin

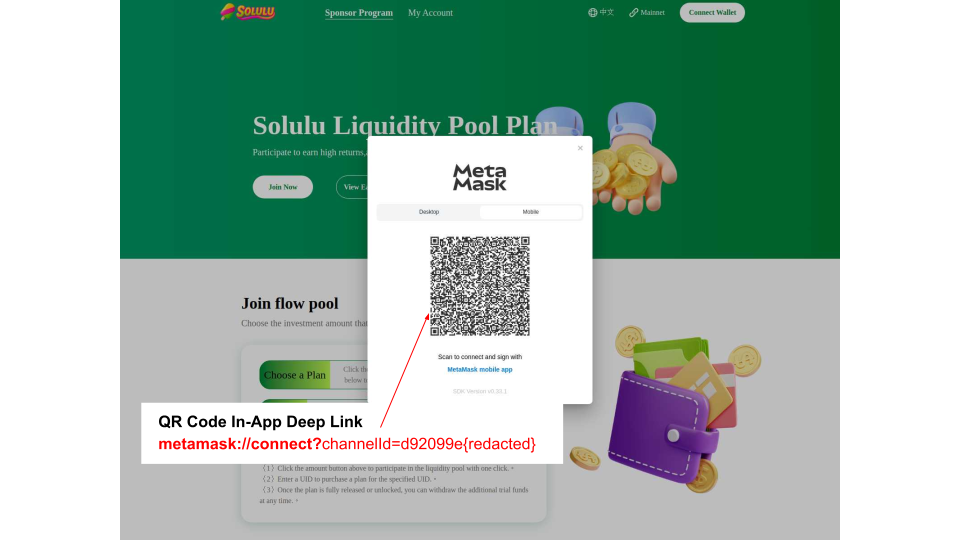

- Metamask

- Trust (wallet)

The familiarity and trust people have with payment-related QR codes create an ideal environment for social engineering attacks, where malicious QR codes can closely mimic legitimate payment requests. Phishing campaigns using pressure tactics can manipulate people into making quick payments.

Below, we share a few examples where an attacker attempts to trigger a financial transaction using a QR code. Figure 7 includes two examples. The first example is a phishing campaign claiming easy returns on investment, asking for an initial payment through a Bitcoin in-app deep link. The second example is a hacking for hire service advertising and providing easy payment with a WeChat payment in-app deep link.

Figure 8 illustrates another get-rich-quick phishing scheme that requests an initial payment through a popular cryptocurrency wallet via a QR code with an in-app deep link.

Messenger Account Takeover Through In-App Deep Links

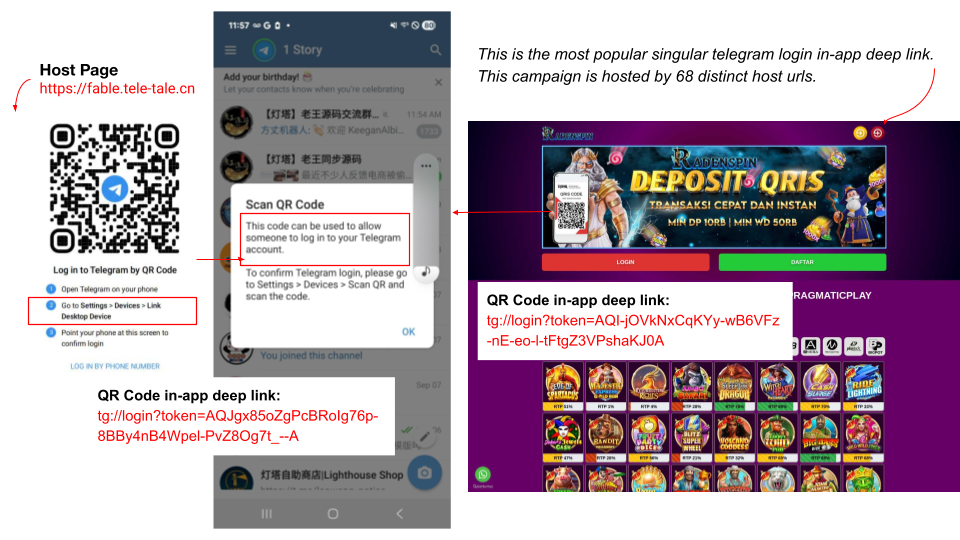

Account takeovers through in-app deep links appear to be a significant phishing vector for messaging and social media sites. Telegram, in particular, was the most prominent application identified in our analysis that uses custom in-app deep links. We found over 35,000 QR codes that contain Telegram in-app deep links such as tg[:]//login or tg[:]//resolve and we observed multiple instances where attackers exploited these links to compromise accounts.

We saw three kinds of Telegram in-app deep links:

- Login

- Resolve

- Proxy

Login accounted for 97% of the Telegram in-app deep links observed. Login grants the QR code creator authorization to access your account.

Previous reporting of Telegram in-app deep link scams warns about these account takeover attacks. Roughly one out of every five host pages with a login Telegram in-app deep link is malicious, based on our conservative estimate.

Figure 9 includes two examples of such Telegram login scams. However, while Telegram is the most popular, attackers are also targeting other popular communication apps.

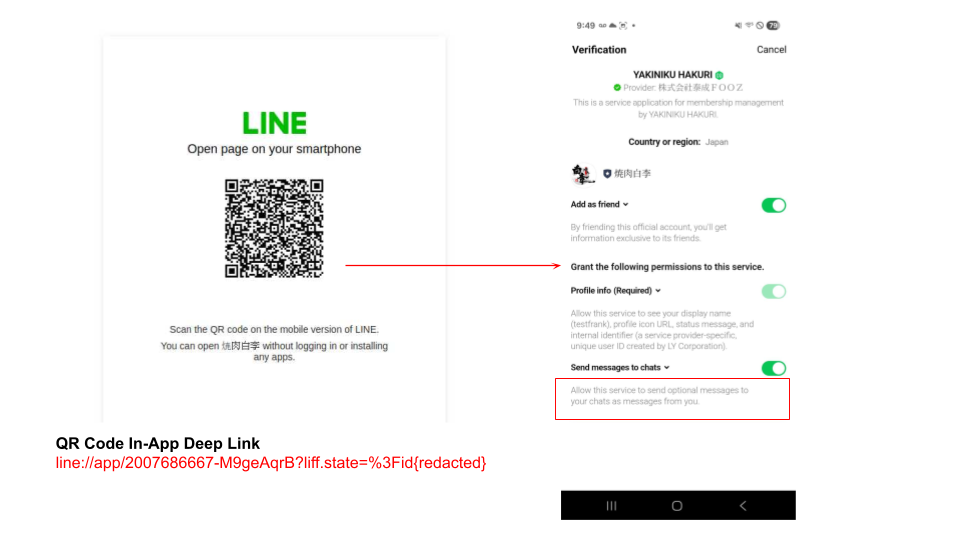

Figure 10 shows an example of a QR code containing an in-app deep link that requests authorization to a target's Line account. This would allow attackers to send Line messages under the device and account owner’s name. Of note, Line has since deprecated this in-app deep link, and the link will now result in an error.

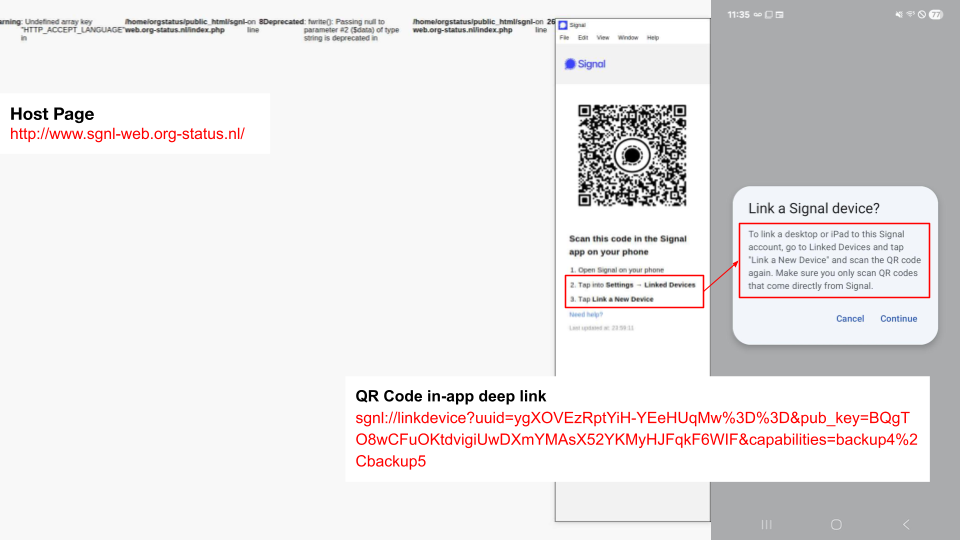

Figure 11 shows an example of a QR code containing an in-app deep link that requests authorization to access a target's Signal account.

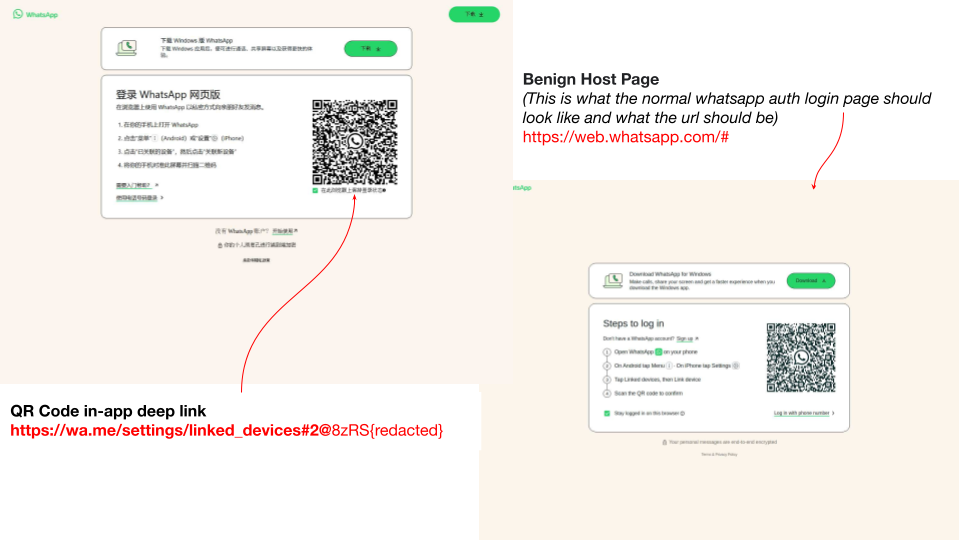

Figure 12 shows an example of a QR code containing an in-app deep link that requests authorization to access a target's WhatsApp account.

In addition to mass phishing campaigns, there's a clear trend toward more focused attacks aimed at stealing Signal credentials. For instance, the Google Threat Intelligence Group (GTIG) has documented increased efforts by Russia state-aligned actors to compromise Signal Messenger accounts. These attacks frequently misuse Signal's feature to link devices with malicious QR codes.

Many of these campaigns have targeted Ukraine in the context of the Russia-Ukraine war. In July 2024, the CERT-UA reported on several threat groups, such as UAC-0185 (aka UNC4221), that have specifically targeted messenger accounts.

Our researchers continue to observe new malicious domains targeting Ukrainian Signal users, including snitch.open-group[.]site and similar variations. After linking a new session to Signal accounts, the attackers can exfiltrate message history and other account information. We have reported discovered information to our Ukrainian cybersecurity partners.

Figure 13 shows a QR code from a campaign targeting Ukraine-based Signal accounts.

Bypassing App Store Security: Direct App Downloads

QR codes are widely used for easy downloading of files and applications. Attackers can exploit this convenience to trick victims into downloading malicious content or installing harmful mobile applications.

Major app stores impose strict security and compliance guidelines to limit the distribution of harmful apps. However, attackers may circumvent these security measures by distributing links to unreviewed Android Package Kit (APK) files hosted on their own servers via QR codes.

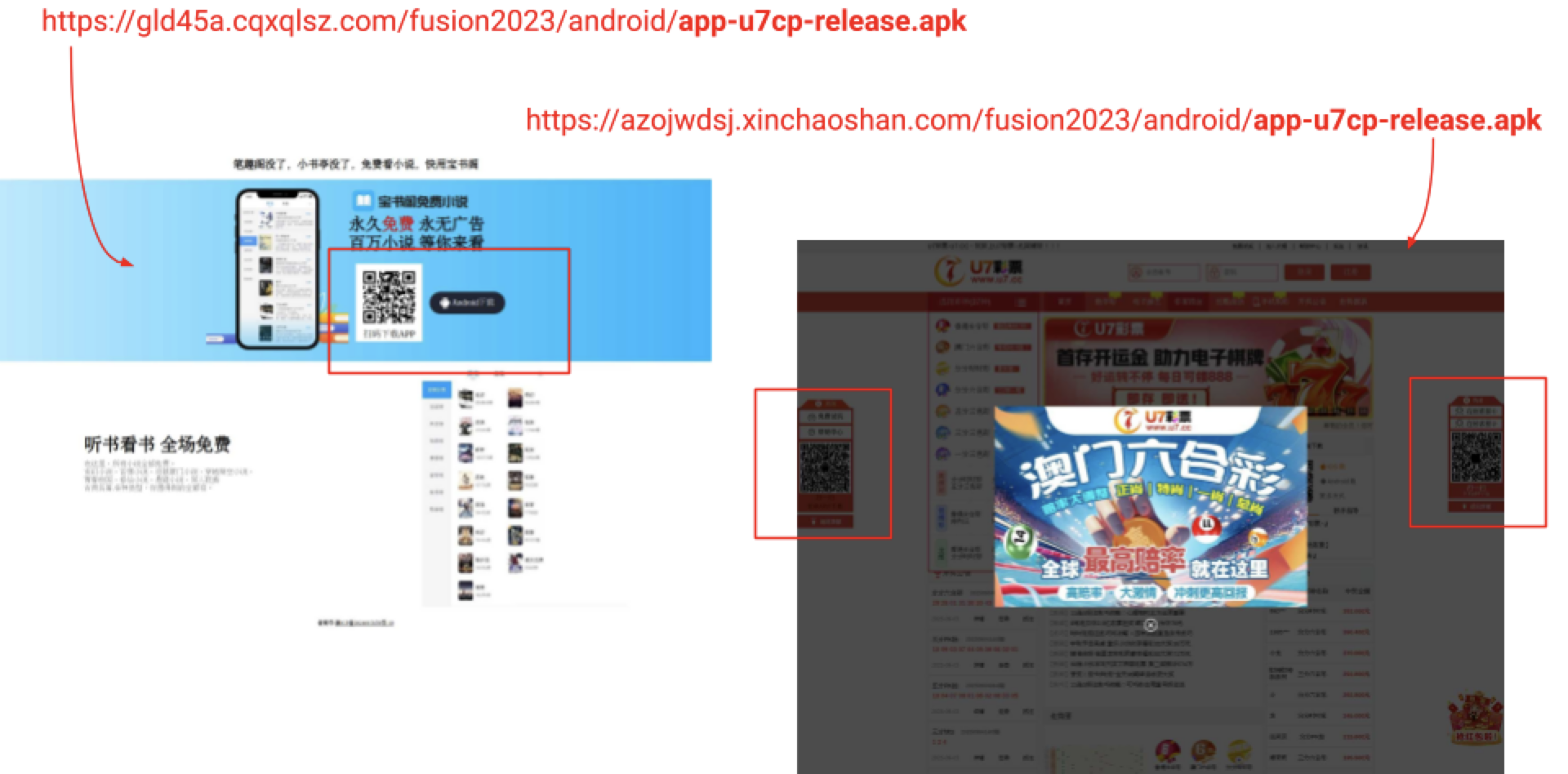

Our investigation identified 59,000 detections of host pages distributing a total of 1,457 distinct APK files directly through QR codes, without going through any app store. Notable examples of these distributed APKs are listed below.

Gambling/Casino App Downloads

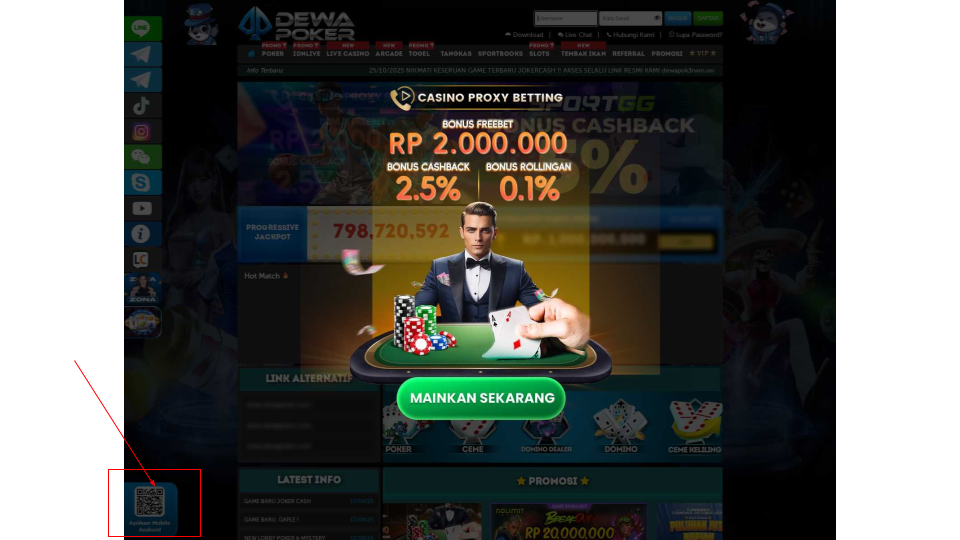

Gambling and casino games websites are distributing their apps through APK files in QR codes.

Figures 14-16 illustrate some examples of such host pages. They are all hosted by many different domains and request certain Android permissions that could be concerning to people.

Figure 14 shows an ad for a popular game that includes a QR code, which redirects the victim to another QR code to download a game app named yicai.apk from f9999[.]app. This QR code is hosted on 10,022 unique URLs.

The app requests read and write permissions to the device's external storage and camera. It also requests install packages permissions.

Figure 14 shows an ad for another game hosted on 9,161 unique URLs. The URL used in Figure 15 is hxxps[:]//pyreneesakbash[.]com/m-nagapoker/android.html. The file for the game is named NagaPocker.apk, and it requests write to external storage and internet permissions.

Figure 16 shows an app distributed through two different pages. Named app-u7cp-release.apk, the app requests:

- Access to coarse location

- Access to fine location

- Background location

- Read and write access to external storage

- Read phone state

- Camera permissions

Warnings from Trustwave about malicious APK files highlight that these types of gambling and betting apps expose victims to harmful activity, such as:

- Excessive advertising

- Theft of personal data

- Theft of funds

- Hidden fees

- Subscriptions

These apps provide financial incentives for engagement, prolonging the life of such scams. Allowing victims to download apps directly and bypassing official app stores enables attackers to circumvent app verification procedures.

Many campaigns hosting QR codes that pointed to a given APK file did so across numerous domains. The apps request suspicious Android permissions, most notably write external storage, camera and access fine location. These permissions could allow intentional data exfiltration, accidental data leakage and surveillance. The aggressive distribution across many different host pages, stealthy methods and excessive permissions suggest malicious intent.

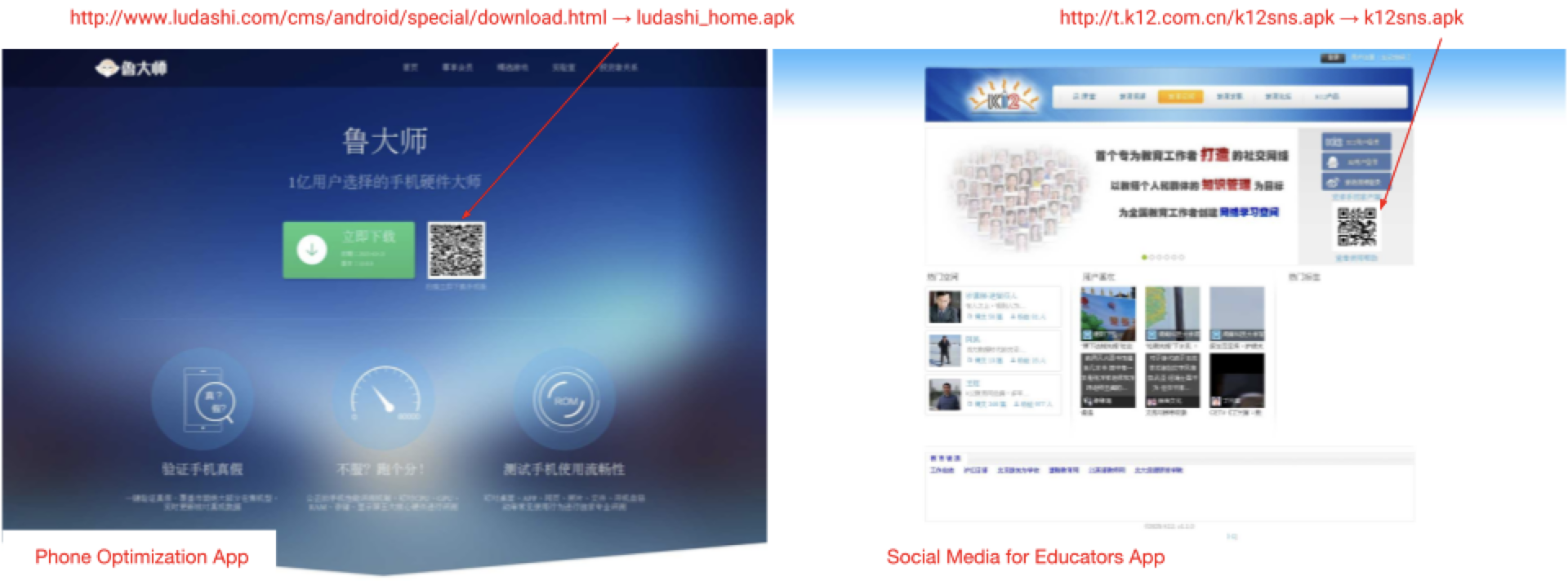

Other Malicious App Downloads

Though gambling apps account for a large portion of the QR codes distributing APK files, QR codes also distribute other kinds of suspicious apps. Figure 17 illustrates two examples.

The first example is a phone optimization app named ludashi_home.apk. It requests the following permissions:

- Recording audio

- Reading battery status

- Reading phone state

- Accessing the camera

- Reading and writing to external storage

- Authenticating accounts

- Clearing the app cache

- Installing packages permissions

The second example is a social network app for educators named k12sns.apk. This app also requests several different types of permissions:

- Accessing the internet

- Reading logs

- Waking the lock

- Reading the phone state

- Writing to external storage

Several vendors detect these apps as suspicious or malicious, and they extract sensitive information from the device they are installed on. For example, the phone optimization app can take on certain behaviors like authenticating accounts and installing further packages, which attackers can misuse for malicious gains.

Conclusion

The attack scenarios and variety of examples we've discovered illustrate the extensive potential and existing prevalence of QR code misuse. The fundamental challenges of this type of misuse are user awareness and lack of visibility from current detection systems.

Most people scanning QR codes don't anticipate the broad range of device functions that can be triggered from in-app deep links or unexpected endpoints from QR code shorteners. This expectation mismatch creates a significant security weak spot that attackers can actively exploit.

User education remains critical — people need to understand that QR codes can do much more than simply open webpages.

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from the threats discussed above through the following products:

Customers using Advanced URL Filtering and Prisma Browser (with Advanced Web Protection) are better protected against various QR code attacks. Our detectors analyze QR code landing pages and deep links.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America: Toll Free: +1 (866) 486-4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- UK: +44.20.3743.3660

- Europe and Middle East: +31.20.299.3130

- Asia: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

- Australia: +61.2.4062.7950

- India: 000 800 050 45107

- South Korea: +82.080.467.8774

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Bradley Duncan and Billy Melicher for the thorough technical review of the article. We would also like to thank the editorial team including Samantha Stallings and Lysa Myers for the assistance with improving and publishing this article.

Indicators of Compromise

Examples of URLs for QR code shorteners:

- hxxps[:]//www.dropbox[.]com/scl/fi/7e8xqrcxgzftrk61omgn0/Presentation.pptx?rlkey=xgk24xllhh4qqv1li2ifd3e3s&st=xvtu5b7y&dl=0

- hxxps[:]//qrco[.]de/bgP6vx

- hxxps[:]//cdnimg.jeayacrai[.]in[.]net/qY42h5ei3SBo9ZmvO!/

Examples of URLs for financial scams:

- hxxp[:]//kccomputech[.]in/babukh1513273

- upi://pay?pa=Q573631163@ybl&pn=PhonePeMerchant&mc=0000&mode=02&purpose=00

- hxxps[:]//20.217.81[.]20

- bitcoin:12wXzmwak8LJ88e1ejupY3brfQi43xdDhb

- hxxps[:]//csdh.wangzhan[.]mobi

- wxp[:]//f2f04lGLqnDoxxeZnftA79yXXU-BeXrgkdYL

- solulu[.]vip

- metamask[:]//connect?channelId=d92099ec-28e3-4eed-97e8-3c40c656f555&v=2&comm=socket&pubkey=021f24e23edc0cbb73440dc2ac94b5a458371cc7c9ce8551b1b68db2196443c2ba&t=q&originatorInfo=eyJ1cmwiOiJodHRwOi8vc29sdWx1LnZpcCIsInRpdGxlIjoid2FnbWkiLCJpY29uIjoiaHR0cDovL3NvbHVsdS52aXAvbG9nby5wbmciLCJzY2hlbWUiOiIiLCJhcGlWZXJzaW9uIjoiMC4zMy4xIiwiZGFwcElkIjoic29sdWx1LnZpcCIsImFub25JZCI6Ijk1ZDcyY2M3LTYwYWYtNGI5Yi1hZTJiLTk4YmE4MDcxZmQwZiIsInBsYXRmb3JtIjoid2ViLWRlc2t0b3AiLCJzb3VyY2UiOiJ3YWdtaSJ9

Examples of URLs and domains for Telegram account takeover:

- hxxps[:]//fable.tele-tale[.]cn

- tg[:]//login?token=AQJgx85oZgPcBRoIg76p-8BBy4nB4Wpel-PvZ8Og7t_--A

- Olb228hoki[.]live

- radenspinrtp[.]cloud

- bostonsportsthenandnow[.]com

- slotolb228[.]com

- tg[:]//login?token=AQI-jOVkNxCqKYy-wB6VFz-nE-eo-l-tFtgZ3VPshaKJ0A

Examples of URLs and domains for Signal account takeover:

- hxxp[:]//www.sgnl-web[.]org-status.nl/

- hxxps[:]//signal-qr[.]org/chatZGtqZmpic2l1NDkzdWpka25zamRucDJ1MDllamtmOThyNGltdmZkZw==/ty62i

- signal.skyriver[.]ch

Examples of phishing domains targeting Ukrainian Signal users:

- snitch.open-group[.]site

- gui.snitch-dev[.]site

- gui.dev-snitch[.]site

- gui.snitch-dev[.]xyz

- gui.dev-snitch[.]xyz

- gui.snitch-dev[.]online

- gui.dev-snitch[.]online

- gui.dev-snitch[.]site

- gui.dev-snitch[.]cloud

- snitch-dev[.]space

- gui-snitch[.]online

- gui-grafit[.]online

- kropyva-group[.]online

Examples of URLs for Line account takeover:

- hxxps[:]//link.members-ms[.]jp/view/clickCount?cst_id=000000000003690&msg_id=0000000000000000000000833677&deli_date=20251029&redirect_uri=hxxps%3A%2F%2Fliff.line.me%2F2007686667-M9geAqrB%3Fid%3D5%3FROUTE_KBN%3D12&msg_type=1&sec_msg=BtBnJY9kxxWnP%2BQt3ycGtVVhajc%3D&sec_date=zVK0EnCA1F8siaD0nf4Nsq1VRlc%3D&sec_uri=P85jU5m9ynEk1wr9ltPW%2Fh%2BJrxE%3D&sec_type=XWWoEGkCR%2BDRAsxfdW4dQHnr%2FbI%3D

- line[:]//app/2007686667-M9geAqrB?liff.state=%3Fid%3D5%253FROUTE_KBN%253D12%26cst_id%3D000000000003690%26msg_id%3D0000000000000000000000833677%26deli_date%3D20251029&liff.referrer=hxxps%3A%2F%2Fbing[.]com%2F&liff.source=lp_qr

Examples of URLs and domains for WhatsApp account takeover:

- hxxps[:]//kzeva2010[.]sbs/MZApUU1aJ3LSYi86IrAZ

- hxxps[:]//wa[.]me/settings/linked_devices#2@vxFKwMU92ToQ60n6gPIw/SLkNcoYVu1XKW+/zMiBEuslO63jfBCCZX/f1mOrkxrAqkp4DaSzq5MX7CcvOJqrNDSJQRLKgXP7K2A=,tZrifOdd4aLBy9nrncQVsa0WqVcYmJnFSs8nEpt3URs=,DfpvHVSe6SmZWxAgVdYXsYz2FsD7DQ3NgmGybCNMHHY=,Ipp5goLgYXXn+7Swuw+pGX77EFECRemAHS5gfOJE7G4=,1

- hxxps[:]//xlq.wpybta[.]icu

- hxxps[:]//wa[.]me/settings/linked_devices#2@8zRSshgXZVfdYcvUvycaOQJlQBcjUDomiqdxC8uQEowH5TQLr/P+1QbxvrXPV4tKg23mqzQeMpPRp3ofr4mePrur/YN4ztk6fWY=,FaknzsibNU+yi9cvuQKDgI3eBh+KEY2TQHqilwZ+KRs=,Rpz7L5S/72o1Ust4Y6CZ3tC7gf6yQvJdd80IFbZzdiw=,eZyTFPAbZWlFUXjGbrvBCM4ApoYT50kFXQb+/cTMzPw=,1

- wswwc[.]icu

- awawc[.]icu

- ve1edm[.]cc

- ve2edm[.]cc

- weppf[.]icu

Examples of URLs hosing APK files for gambling game

- hxxps[:]//gricanjolt[.]com?r=aHR0cHM6Ly9mOTk5OS5hcHA=1

- hxxps[:]//pyreneesakbash[.]com/m-nagapoker/android[.]html

- hxxps[:]//resourcepro.tycheint[.]com/yicai[.]apk

- hxxps[:]//90999.fdjk34sddsf90999[.]cc/xincai[.]apk

- hxxps[:]//gld45a.cqxqlsz[.]com/fusion2023/android/app-u7cp-release[.]apk

- hxxps[:]//azojwdsj.xinchaoshan[.]com/fusion2023/android/app-u7cp-release[.]apk

- hxxp[:]//www.ludashi[.]com/cms/android/special/download[.]html hxxp[:]//t.k12[.]com[.]cn/k12sns[.]apk

Additional Resources

- Deep Link - Android, Google

- Evolution of Sophisticated Phishing Tactics: The QR Code Phenomenon – Unit 42, Palo Alto Networks

- Myth Busting: Why "Innocent Clicks” Don’t Exist in Cybersecurity – Unit 42, Palo Alto Networks

- Phishing Activity Trends Report Q1 2025 [PDF] – Anti-Phishing Working Group (APWG)

- Telegram QR Phishing Threat: Account Takeover with a Single Scan - CIP blog, Criminal IP

- Signals of Trouble: Multiple Russia-Aligned Threat Actors Actively Targeting Signal Messenger – Google Threat Intelligence Group (GITG), Google

- Unmasking Malicious APKs: Android Malware Blending Click Fraud and Credential Theft – Trustwave, A LevelBlue Company

- Dangerous new Android malware adds fake contacts to your phone while draining bank accounts — how to stay safe – Tom’s Guide

- Phishing Alert: Calendar-Based Phishing Attack – Trinity College

- Unit 42 Cryptocurrency Scam Chatbot Activity – Unit 42, Palo Alto Networks

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42