Executive Summary

Unit 42 researchers recently investigated a phishing campaign targeting European companies, including in Germany and the UK. Our investigation revealed that the campaign aimed to harvest account credentials and take over the victim’s Microsoft Azure cloud infrastructure.

The campaign’s phishing attempts peaked in June 2024, with fake forms created using the HubSpot Free Form Builder service. Our telemetry indicates the threat actor successfully targeted roughly 20,000 users across various European companies.

Our investigation revealed that while the campaign appears to have begun in June 2024, the phishing campaign was still active as of September 2024. The campaign targeted European companies in the following industries:

- Automotive

- Chemical

- Industrial compound manufacturing

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from the threats discussed in this article through the following products and services:

- Advanced WildFire

- Advanced URL Filtering and Advanced DNS Security

- Cortex XDR and XSIAM

- Unit 42 Managed Services Team

If you think you might have been compromised or have an urgent matter, contact the Unit 42 Incident Response team.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Phishing, Malicious Domains, Microsoft Azure |

The Phishing Operation

In June 2024, Unit 42 researchers identified a phishing campaign targeting at least 20,000 European automotive, chemical and industrial compound manufacturing users. The phishing emails contained either an attached Docusign-enabled PDF file or an embedded HTML link directing victims to malicious HubSpot Free Form Builder links embedded within phishing emails. HubSpot is a cloud-based customer relationship management (CRM), marketing, sales and content management system (CMS) operation platform.

Working with HubSpot security teams, we determined that HubSpot was not compromised during this phishing campaign, nor were the Free Form Builder links delivered to target victims via HubSpot infrastructure.

We reached out to Docusign and they responded with, “The trust, security and privacy of our customers has always been at the core of Docusign’s business. Since the time of this investigation, Docusign has implemented a number of additional actions to strengthen our proactive preventative measures, which — to date — have significantly decreased the number of signers receiving fraudulent Docusign signature requests.”

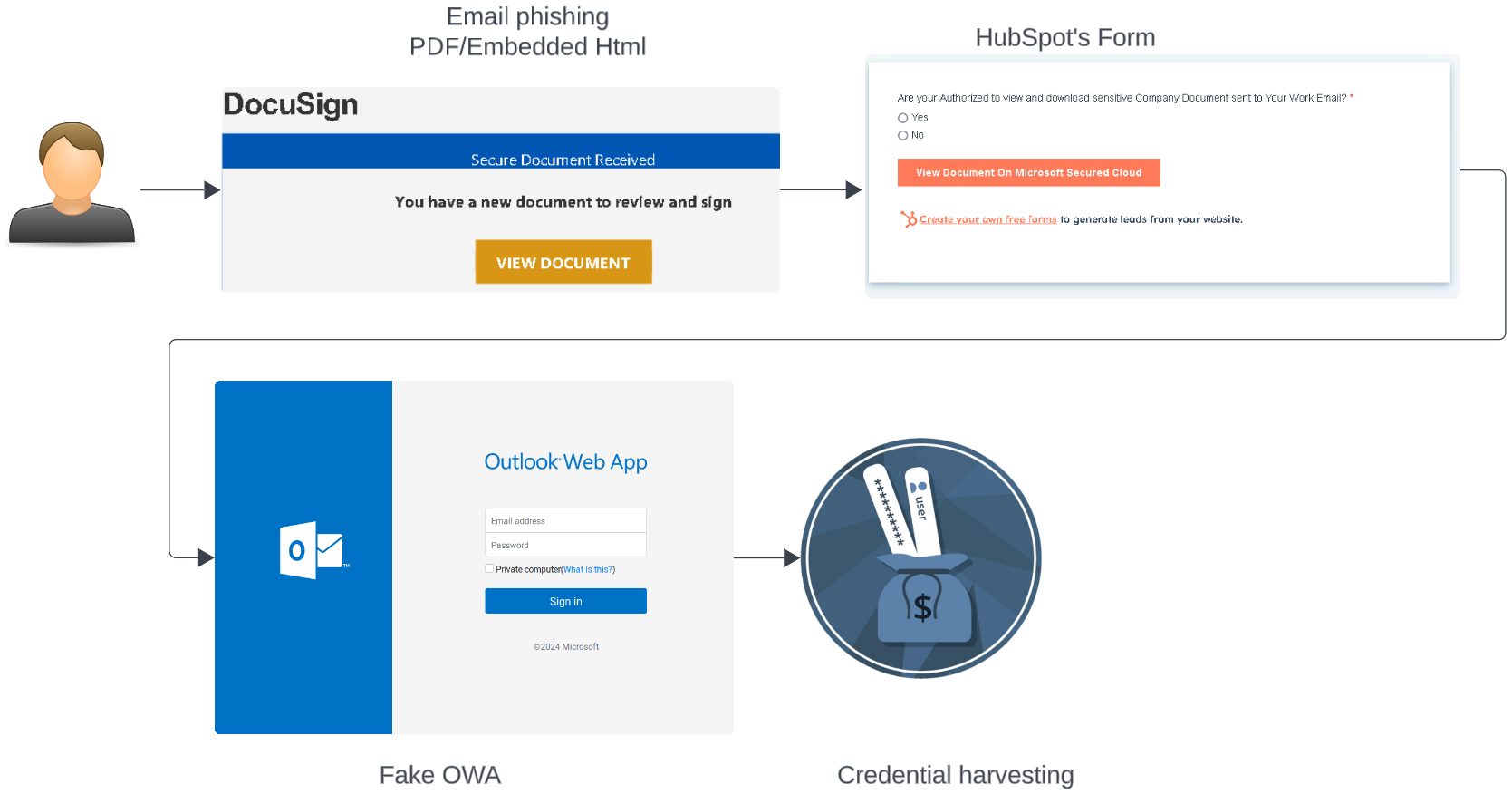

Figure 1 shows a simplified diagram of the phishing operation. Attackers sometimes used two levels of redirection to reach their credential harvesting infrastructure.

Evidence showed that the threat actor targeted several phishing attempts toward specific organizations. These phishing attempts came complete with thematic dialogue specific to that organization’s brand and email address formatting.

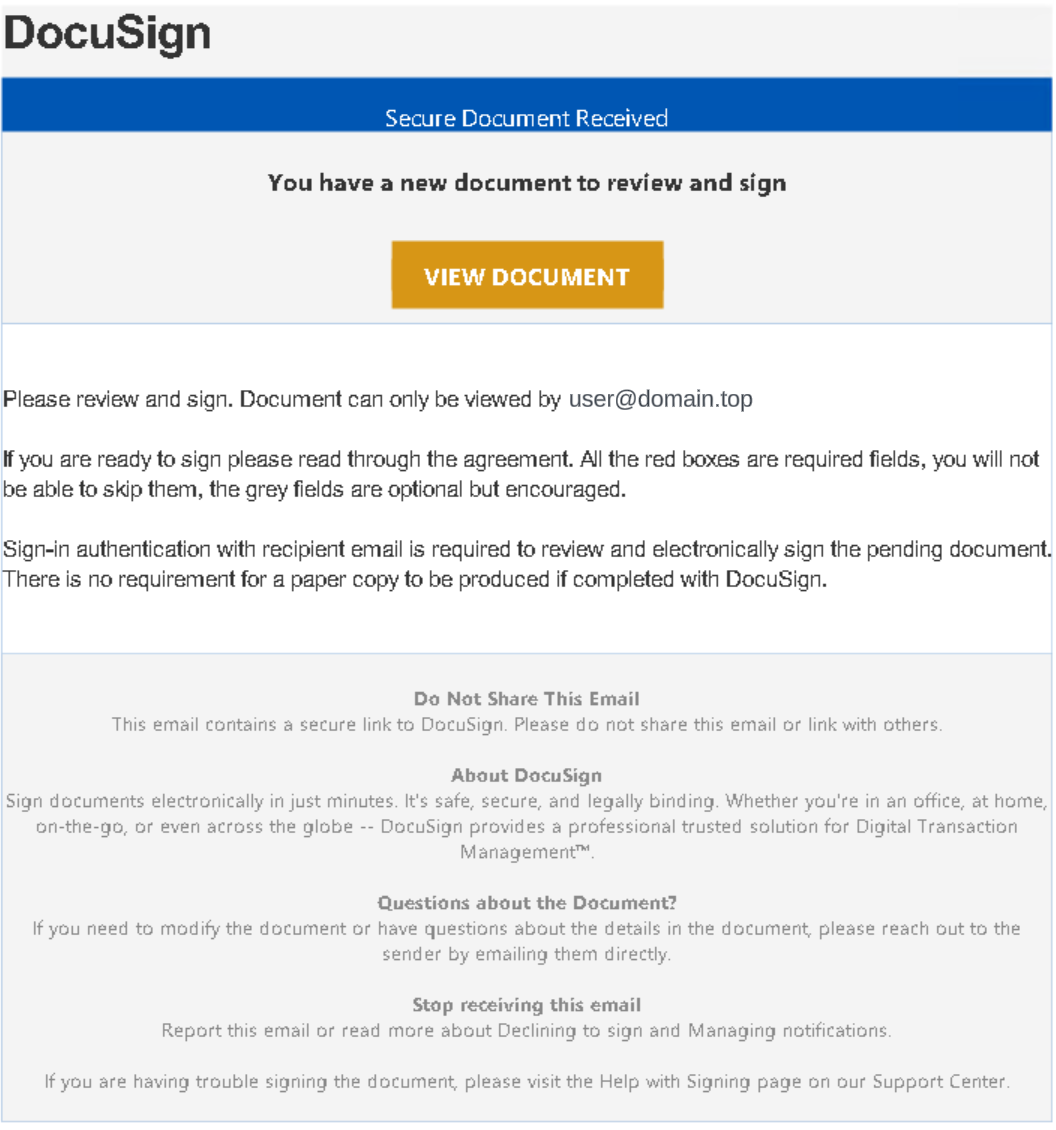

Several malicious PDF attachments used the target organization’s name in the file name, (i.e., CompanyName.pdf). Figure 2 shows an example of a malicious PDF file mimicking a Docusign document.

Clicking “View Document” would redirect the victim to a Free Form with the following URL format: https://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/FORM-ID.

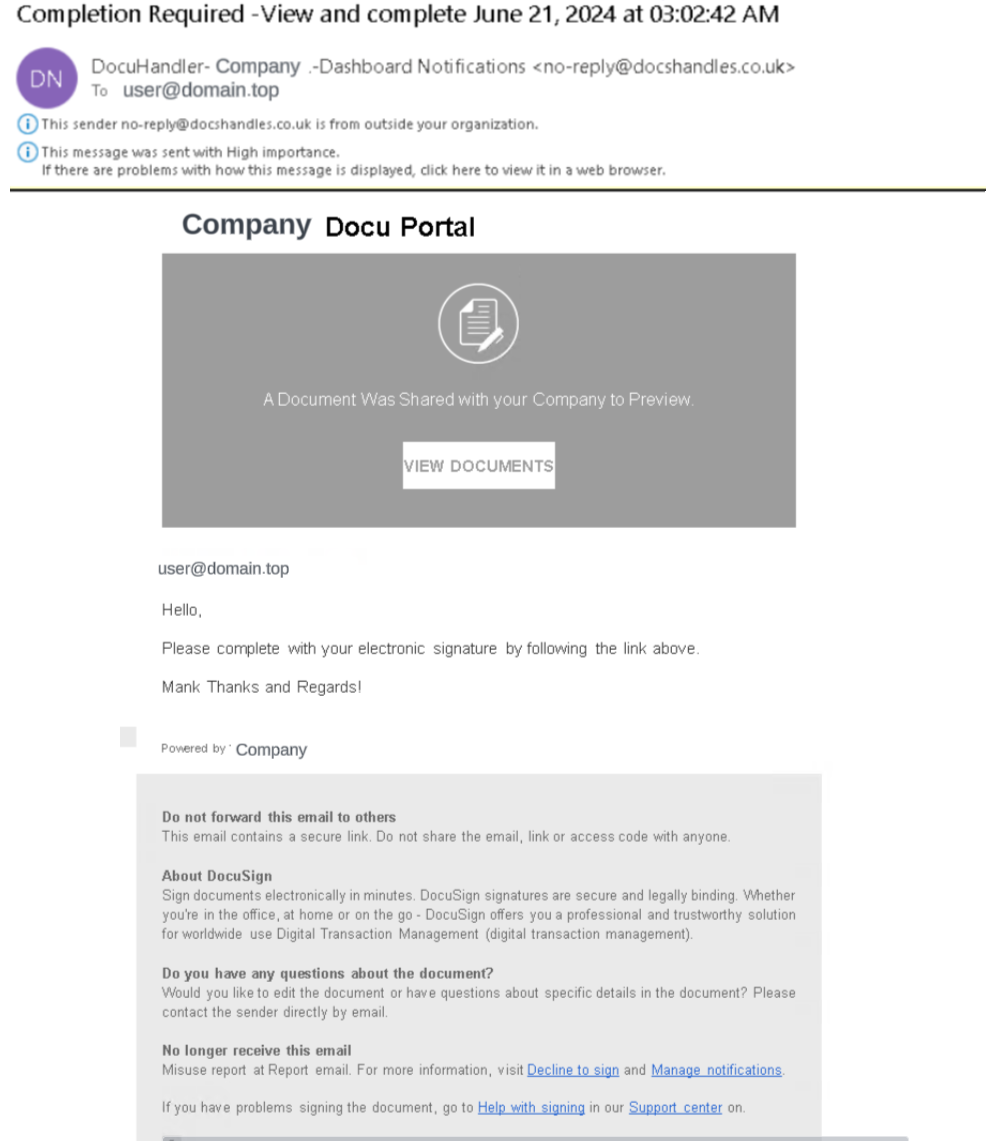

Figure 3 shows an example of a phishing attempt with embedded HTML.

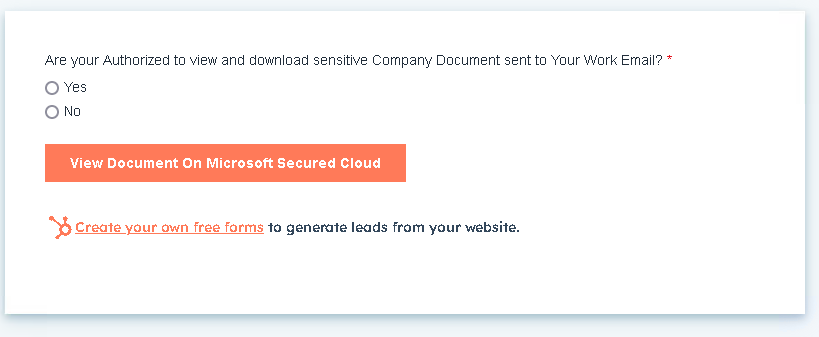

Both the malicious PDF and HTML examples led victims to the Free Form window shown in Figure 4 if they clicked through.

The wording in the Free Form window “View Document on Microsoft Secured Cloud” indicates that the phishing campaign is also targeting Microsoft accounts. We verified that the phishing campaign did make several attempts to connect to the victim’s Microsoft Azure cloud infrastructure.

Once the user clicked “View Document on Microsoft Secured Cloud,” they were redirected to the threat actor’s credential harvesting pages. This page prompted the victim to supply their login information for Microsoft Azure.

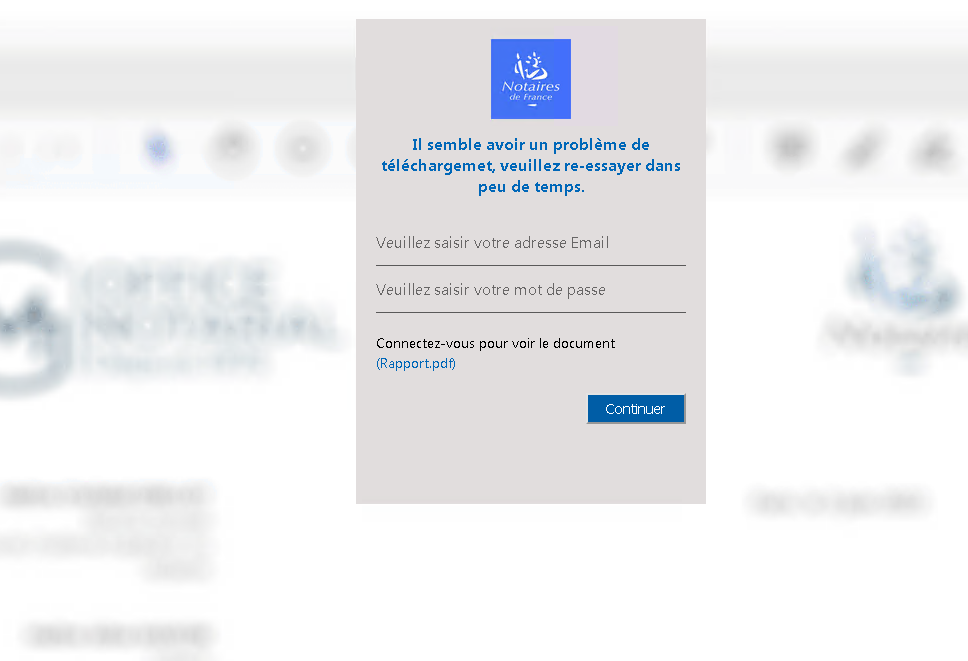

We also found evidence that this phishing campaign targeted users of European organizations. Figure 5 below is an example of a phishing website designed to target notaries in France.

Although this phishing setup differs from the one we mentioned previously, we found the attackers reused the same infrastructure. This infrastructure included the registered first-level domain, which we’ll describe in more detail in a later section.

A list of the Free Form URLs identified during this investigation is included in the Indicators of Compromise section of this article.

Identifying Suspicious Phishing Emails

By analyzing the phishing emails, we found two indicators helpful to identify similar attacks. One was a tone of urgency, and the other was failing its authentication checks.

Both of these are well-known phishing indicators, but due to their importance, we have summarized each.

- Tone of urgency:

- Phishing emails often create urgency with phrases like “immediate action required” to pressure quick responses

- Failed authentication checks:

- A “Fail” outcome for the Sender Policy Framework (SPF) means the sender’s IP address is unauthorized to send emails on behalf of the domain, suggesting possible spoofing

- A “Fail” outcome for DomainKeys Identified Mail (DKIM) indicates the email’s digital signature was not verified, implying it could have been altered or forged

- A “Temporary Error” for Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting and Conformance (DMARC) points to a short-term issue with domain alignment, often due to server or DNS delays, weakening domain authentication.

Note: DMARC relies on successful SPF and DKIM checks to confirm domain legitimacy, providing protection against spoofing and phishing.

In the snippet below, from the original mail attribute, we can see the suspicious indicators mentioned above.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 |

"Subject": "Completion Required XXXXXXXXX ", "AuthDetails": [ { "Name": "SPF", "Value": "Fail" }, { "Name": "DKIM", "Value": "Fail" }, { "Name": "DMARC", "Value": "Temporary error" }, ], |

Initial Access and Evasion Techniques

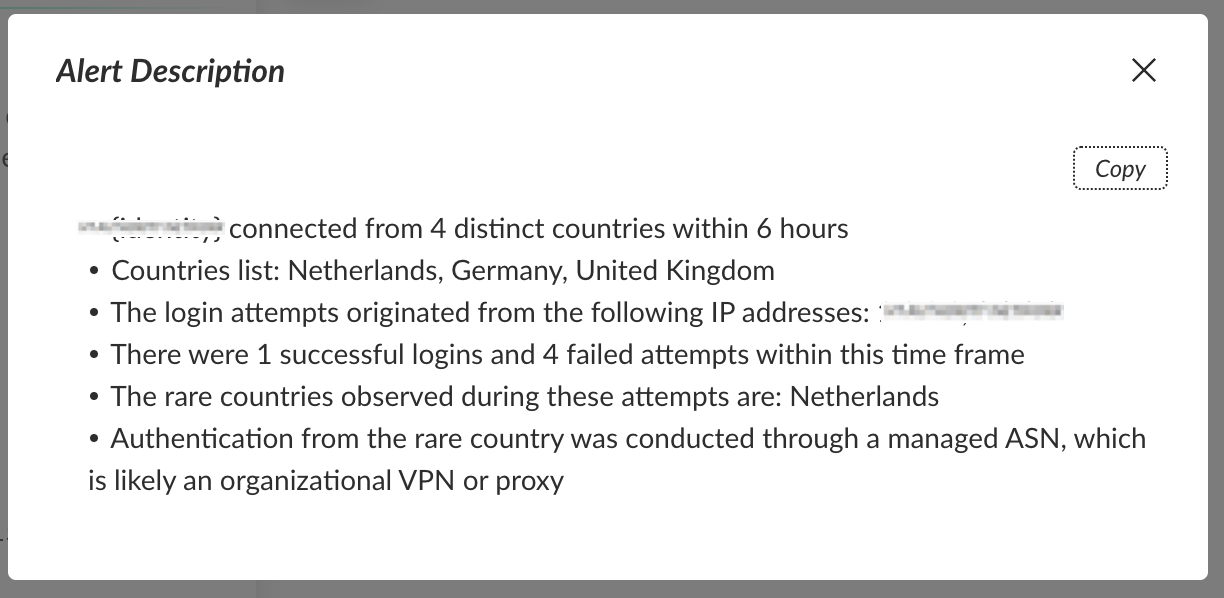

Adding their device to the authentication process allowed the threat actor to make their logins appear to come from a trusted device. By using VPN proxies, the threat actor’s login attempts originated from the same country as the victim organization. However, Figure 6 shows that there were instances of login attempts from previously blocked regions.

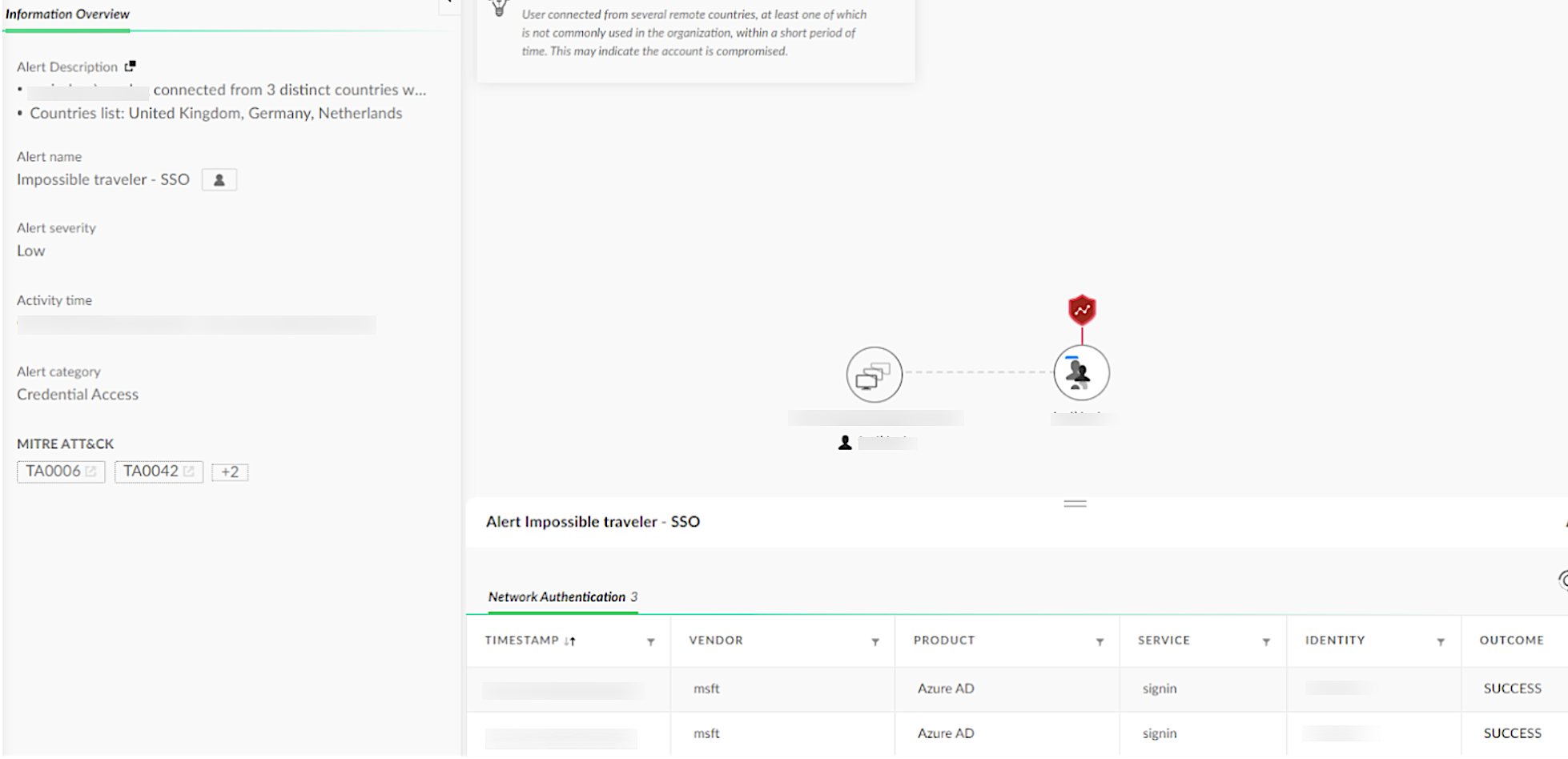

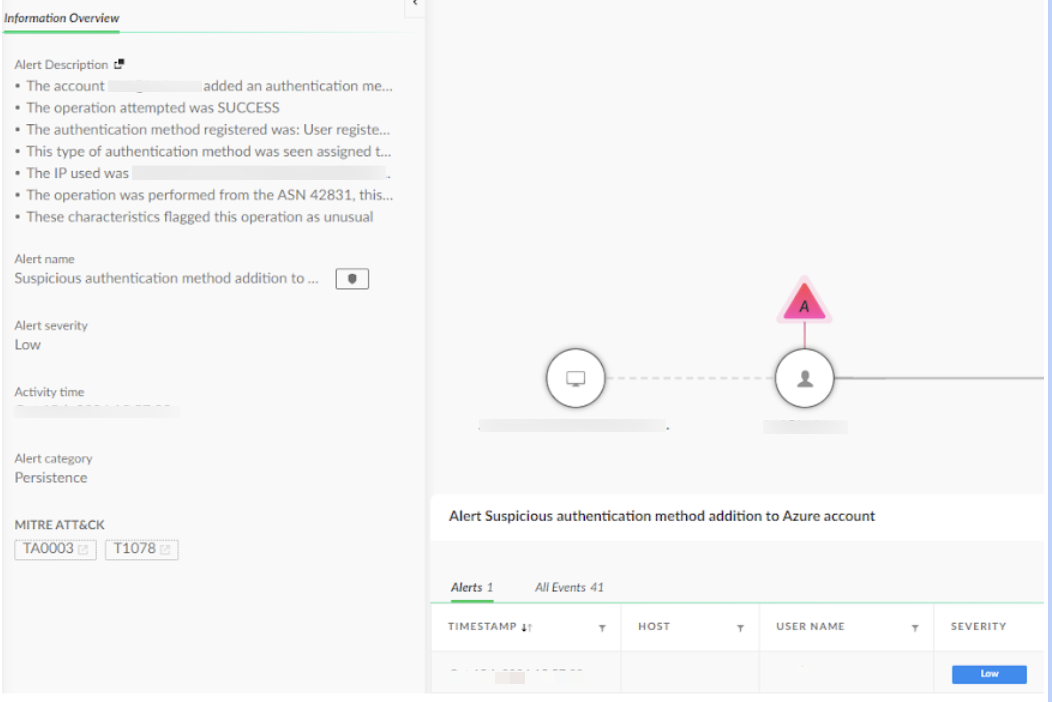

Figure 7 provides an example of an alerting event in Cortex. These alerts identify login events from uncommon or suspicious sources.

We also identified the use of a new Autonomous System Number (ASN) that had not been seen in prior user activity. This added another layer of suspicion. Figure 8 shows another example of an alerting event that can notify security teams of malicious login attempts.

Finally, the threat actor employed unusual user-agent strings during their connection attempts to the victim systems. An example of this custom user-agent string from the phishing campaign was as follows:

|

1 |

Client=OWA;Action=ViaProxy |

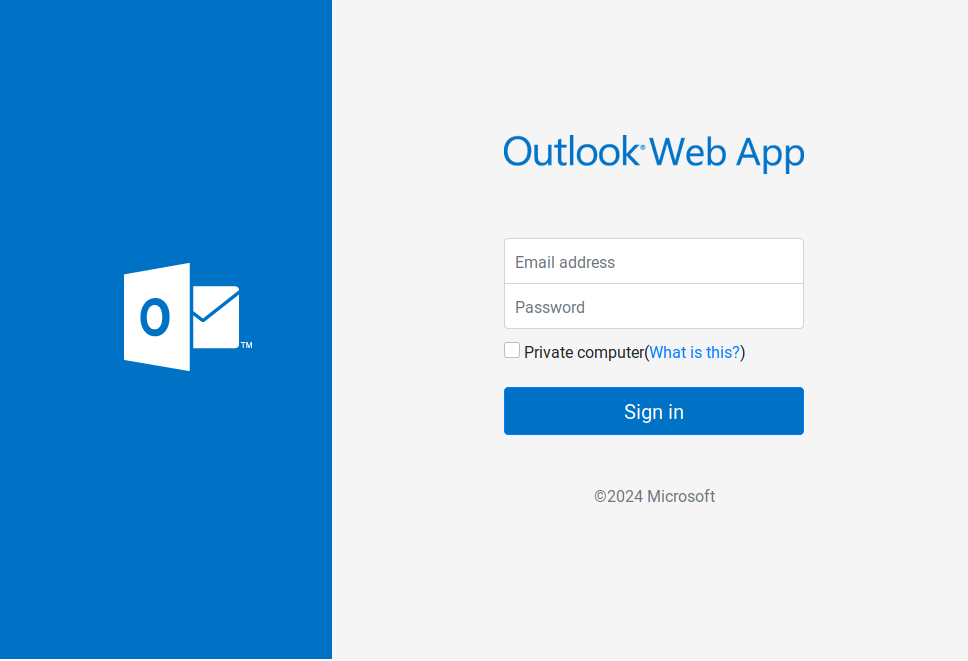

The Phishing Redirection

During the investigation, we identified at least 17 working Free Forms used to redirect victims to different threat actor-controlled domains. The majority of the identified domains were hosted at the top-level domain .buzz. Each of the identified Free Forms contained a similar Microsoft Outlook Web App landing page design and redirection pattern, shown in Figure 9.

At the time of our investigation, the majority of the servers we identified that were hosting phishing content used by the threat actor were offline. However, we did find that two of these host servers were active, allowing us to collect the phishing page source code. Both of the phishing source code samples that we captured had the same structure.

The phishing code used a Base64-encoded URL designed for credential harvesting and redirecting the victims to a Microsoft Outlook Web Access (OWA) login page. Figure 10 shows a screenshot of the source code from the phishing page.

The sample source code revealed that the phishing links led victims to websites using a URL that simulated the target victim organization’s name. The phishing websites presented to the victim included their organization’s name followed by the top-level domain .buzz (i.e., http[:]//www.acmeinc[.]buzz):

- hxxps://<victim>.buzz/doc0024/index.php

- hxxps://<victim>.buzz/2doc5/index.php

The Phishing Infrastructure

The phishing campaign was hosted across various services, including Bulletproof VPS hosts. This is a hosting service known for providing a high degree of anonymity, lax enforcement of legal regulations and resistance to being shut down. They are often associated with malicious operations, including phishing operations.

One of the more interesting findings for us was the infrastructure clusters we analyzed, from the compromised and targeted users we identified. By analyzing telemetry collected from the victims, we found that the threat actor used the same hosting infrastructure for multiple targeted phishing operations. They also used this infrastructure for accessing compromised Microsoft Azure tenants during the account takeover operation.

Figure 11 shows an example of such a cluster. The top line of the diagram, the user layer, is indicated with the number 1. The victims are anonymized so as not to identify the targeted and compromised users.

According to our telemetry, User A was compromised, resulting in their Microsoft Azure tenant credentials also being exposed. Connections labeled with the word access and indicated with the number 2 revealed that the threat actor used the same phishing hosting infrastructure for network connection access to the compromised user’s system.

The same infrastructure being used for both the phishing hosting infrastructure as well as the direct connection to the victim environments suggests that the threat actor owned the hosted server instead of renting or subscribing to a shared “hosting” service.

The website forklog[.]com, indicated by the number 3 in the diagram, is an online publication presented in both Russian and Ukrainian languages. The contents of the publication focus on cryptocurrencies and blockchain technologies. This domain was used by the threat actors within one of their victim’s environments and points to a potential means of future victim targeting or income generation.

We also found the compromised company associated with User A had a publicly exposed control panel associated with a web hosting platform used to run and automate cloud-based applications.

We found that the threat actor consistently scanned the control panel from the same phishing infrastructure that deployed the phishing campaign redirection hosts. We did not identify any successful attempts to access the control panel.

Persistence

During the account takeover, the threat actor added a new device to the victim’s account. This allowed persistent access to the account, even as security efforts were made to lock them out. Figure 12 displays an alert of suspicious resource creation within the Microsoft Azure tenant.

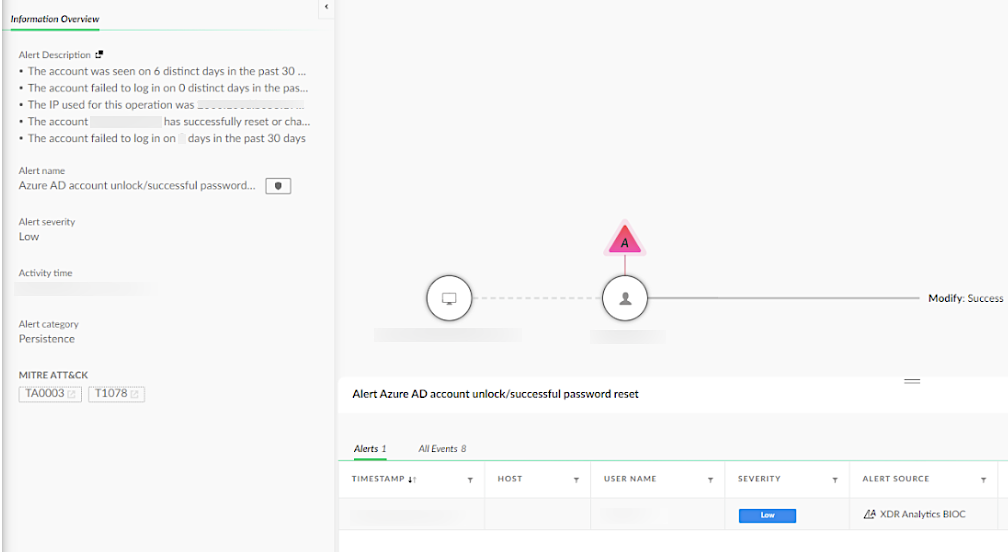

When IT regained control of the account, the attacker immediately initiated a password reset, attempting to regain control. This created a tug-of-war scenario in which both parties struggled for control over the account. This resulted in several additional alerts being triggered within the organization, shown in Figure 13.

Conclusion

In this article, we reviewed a phishing campaign that targeted European companies, including German and UK automakers and chemical manufacturing organizations. Threat actors directed the phishing campaign to target the victim’s Microsoft Azure cloud infrastructure via credential harvesting attacks on the phishing victim’s endpoint computer. They then followed this activity with lateral movement operations to the cloud.

The campaign’s phishing operation, which leveraged HubSpot Free Form builder services, peaked in June 2024. We believe the threat actor successfully compromised multiple victims in different companies across the targeted countries.

Unit 42 researchers have an open dialogue with HubSpot in relation to the phishing operations leveraging their services and have worked with them to develop notifications and mitigation strategies. We have also worked with the compromised organizations to ensure they have the resources they need to recover from the phishing operation.

Detection and Mitigations

For Palo Alto Networks customers, our products and services provide the following coverage associated with this group:

- Advanced WildFire cloud-delivered malware analysis service accurately identifies the known samples as malicious.

- Advanced URL Filtering and Advanced DNS Security identify domains associated with this group as malicious.

- Cortex XDR and XSIAM detect user and credential-based threats by analyzing user activity from multiple data sources including endpoints, network firewalls, Active Directory, identity and access management solutions, and cloud workloads. Cortex builds behavioral profiles of user activity over time with machine learning. By comparing new activity to past activity, peer activity and the expected behavior of the entity, Cortex detects anomalous activity indicative of credential-based attacks.

- Unit 42 Managed Detection and Response Service delivers continuous 24/7 threat detection, investigation and response/remediation to customers of all sizes globally.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Appendix

MITRE Techniques

| Alert Name | Alert Source | ATT&CK Technique |

|---|---|---|

| First SSO access from ASN in organization | XDR Analytics BIOC, Identity Analytics | Valid Accounts: Domain Accounts (T1078.002) |

| First connection from a country in organization | XDR Analytics BIOC, Identity Analytics | Compromise Accounts (T1586) |

| Impossible traveler - SSO | XDR Analytics, Identity Analytics | Compromise Accounts (T1586) |

| Suspicious authentication method addition to Azure account | XDR Analytics, Identity Analytics | Persistence (TA0003) |

| Azure AD account unlock/password reset attempt | XDR Analytics BIOC, Identity Analytics | Persistence (TA0003) |

| SSO with abnormal user agent | XDR Analytics BIOC, Identity Analytics | Initial Access (TA0001) |

| Abnormal Communication to a Rare Domain | XDR Analytics BIOC, Network Analytics | Command and Control (TA0011) |

Indicators of Compromise

HubSpot Free Form URL Links

- hxxps://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/1P_6IFHnbRriC_DG56YzVhw2dz72l

- hxxps://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/1UgPJ18suRU-NEpmYkEwteg2ec0io

- hxxps://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/12-j0Y4sfQh-4pEV6VKVOeg2dzmbq

- hxxps://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/1cJJXJ0NfTPOKwn23oAmmzQ2e901x

- hxxps://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/1wg25r1Z-R5GkhY6k-xGzOg2dvcv5

- hxxps://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/1G-NQN9DbSVmDy1HDeovJCQ2ebgc6

- hxxps://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/1AEc2-gS4TuyQyAiMQfB5Qw2e5xq0

- hxxp://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/1wg25r1Z-R5GkhY6k-xGzOg2dvcv5

- hxxps://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/1zP2KsosARaGzLqdj2Umk6Q2ekgty

- hxxps://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/1fnJ8gX6kR_aa5HlRyJhuGw2ec8i2

- hxxps://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/1QPAfZcocSuu3AnqznjU14A2eabj0

- hxxps://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/176T8k3N9Q562OEEfhS22Fg2ebzvj

- hxxps://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/18wO3Zb9hTIuittmhHvQFuQ2ec8gt

- hxxps://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/1vNr8tB1GS4mZuYg81ji3dg2e08a3

- hxxps://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/1qe8ypRpdTr284rkNpgmoow2ebzty

- hxxps://share-eu1.hsforms[.]com/1C1IZ0_b-SD6YXS66alL4EA2e90m9

Phishing Infrastructure URLs - Level 1

- hxxps://technicaldevelopment.industrialization[.]buzz/?o0B=RLNT

- hxxps://vigaspino[.]com/2doc5/index.php?submissionGuid=1d51a08d-cf55-4146-8b5b-22caa765ac85

- hxxps://technicaldevelopment.rljaccommodationstrust[.]buzz/?WKg=2Ljv8

- hxxps://purchaseorder.vermeernigeria[.]buzz/?cKg=C3&submissionGuid=4631b0c9-5e10-4d81-b1d6-4d01045907e7

- hxxps://asdrfghjk3wr4e5yr6uyjhgb.mhp-hotels[.]buzz/?Nhv3zM=xI7Kyf

- hxxps://purchaseorder.europeanfreightleaders[.]buzz/?Mt=zqoE&submissionGuid=476f32d0-e667-4a18-830b-f57a2b401fc3

- hxxps://orderspecification.tekfenconstruction[.]buzz/?6BI=AmaPH&submissionGuid=e2ce33ea-ee47-4829-882c-592217dea521

- hxxps://asdrfghjk3wr4e5yr6uyjhgb.mhp-hotels[.]buzz/?Nhv3zM=xI7Kyf

- hxxps://d2715zbmeirdja.cloudfront[.]net/?__hstc=251652889.fcaff35c15872a69c6757196acd79173.1727206111338.1727206111338.1727206111338.1&__hssc=251652889.158.1727206111338&__hsfp=1134454612&submissionGuid=30359eaf-a821-472d-ba17-dd2bd0d96b96

- hxxps://docusharepoint.fundament-advisory[.]buzz/?3aGw=Nl9

- hxxps://wr43wer3ee.cyptech[.]com[.]au/oeeo4/ewi9ew/mnph_term=?/&submissionGuid=50aa078a-fb48-4fec-86df-29f40a680602

- hxxp://orderconfirmation.dgpropertyconsultants[.]buzz/

- hxxps://espersonal[.]org/doc0024/index.php?submissionGuid=6e59d483-9dc2-48f8-ad5a-c2d2ec8f4569

- hxxps://vigaspino[.]com/2doc5/index.php?submissionGuid=093410a5-c228-4ddf-890c-861cdc6fe5d8

- hxxps://technicaldevelopment.industrialization[.]buzz/?o0B=RLNT

- hxxps://espersonal[.]org/doc0024/index.php?submissionGuid=96a9b82a-55d3-402d-9af4-c2c5361daf5c

- hxxps://orderconfirmating.symmetric[.]buzz/?df=ZUvkMN&submissionGuid=e06a1f83-c24e-4106-b415-d2f43a06a048

Phishing Infrastructure URLs - Level 2

- hxxps://docs.doc2rprevn[.]buzz?username=

- hxxps://docusharepoint.fundament-advisory[.]buzz/?3aGw=Nl9

- hxxps://9qe.daginvusc[.]com/miUxeH/

- hxxps://docs.doc2rprevn[.]buzz/?username=

- hxxps://vomc.qeanonsop[.]xyz/?hh5=IY&username=ian@deloitte.es

- hxxps://sensational-valkyrie-686c5f.netlify[.]app/?e=

IP Addresses

- 167.114.27[.]228

- 144.217.158[.]133

- 208.115.208[.]118

- 13.40.68[.]32

- 18.67.38[.]155

- 91.92.245[.]39

- 91.92.244[.]131

- 91.92.253[.]66

- 94.156.71[.]208

- 91.92.242[.]68

- 91.92.253[.]66

- 188.166.3[.]116

- 104.21.25[.]8

- 172.67.221[.]137

- 49.12.110[.]250

- 74.119.239[.]234

- 208.91.198[.]96

- 94.46.246[.]46

PDFs

- (Zoomtan.pdf) b2ca9c6859598255cd92700de1c217a595adb93093a43995c8bb7af94974f067

- (Belzona.pdf) f3f0bf362f7313d87fcfefcd6a80ab0f18bc6c5517d047be186f7b81a979ff91

- (Pcc.pdf) deff0a6fbf88428ddef2ee3c4d857697d341c35110e4c1208717d9cce1897a21

XDR Queries

Cortex XDR queries to detect the presence of the operations explained within the article can be found in the link on our GitHub.

Points To Consider During Remediation

- Microsoft Entra ID consideration:

- Ensure that any compromised user's Microsoft Entra ID account is disabled until any ongoing investigation and eradication operations are completed.

- Revoke users’ session:

- When marking a user as compromised in Azure Entra ID, using the “revoke sessions” function, be aware that this action will not terminate active sessions.

- Revoking sessions will only invalidate the Primary Refresh Token, allowing the threat actor to maintain access until their current Access Token expires, typically within 60-90 minutes.

- While you should still mark the user as compromised and revoke sessions to prevent new access tokens from being issued, consider implementing Continuous Access Evaluation to address this limitation and enhance security by allowing real-time session management.

- Disable “Self-Service Tenant Creation”:

- This feature enables internal users to create a new tenant, which threat actors may exploit to exfiltrate data.

Updated Dec. 19, 2024, at 10:25 a.m. PT to clarify verbiage.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42