Executive Summary

Since November, geopolitical tensions between Russia and Ukraine have escalated dramatically. It is estimated that Russia has now amassed over 100,000 troops on Ukraine's eastern border, leading some to speculate that an invasion may come next. On Jan. 14, 2022, this conflict spilled over into the cyber domain as the Ukrainian government was targeted with destructive malware (WhisperGate) and a separate vulnerability in OctoberCMS was exploited to deface several Ukrainian government websites. While attribution of those events is ongoing and there is no known link to Gamaredon (aka Primitive Bear), one of the most active existing advanced persistent threats targeting Ukraine, we anticipate we will see additional malicious cyber activities over the coming weeks as the conflict evolves. We have also observed recent activity from Gamaredon. In light of this, this blog provides an update on the Gamaredon group.

Since 2013, just prior to Russia’s annexation of the Crimean peninsula, the Gamaredon group has primarily focused its cyber campaigns against Ukrainian government officials and organizations. In 2017, Unit 42 published its first research documenting Gamaredon’s evolving toolkit and naming the group, and over the years, several researchers have noted that the operations and targeting activities of this group align with Russian interests. This link was recently substantiated on Nov. 4, 2021, when the Security Service of Ukraine (SSU) publicly attributed the leadership of the group to five Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) officers assigned to posts in Crimea. Concurrently, the SSU also released an updated technical report documenting the tools and tradecraft employed by this group.

Given the current geopolitical situation and the specific target focus of this APT group, Unit 42 continues to actively monitor for indicators of their operations. In doing so, we have mapped out three large clusters of their infrastructure used to support different phishing and malware purposes. These clusters link to over 700 malicious domains, 215 IP addresses and over 100 samples of malware.

Monitoring these clusters, we observed an attempt to compromise a Western government entity in Ukraine on Jan. 19, 2022. The sections below offer an overview of our findings in order to aid targeted entities in Ukraine as well as cybersecurity organizations in defending against this threat group.

Update Feb. 16: When we originally published this report, we noted, “While we have mapped out three large clusters of currently active Gamaredon infrastructure, we believe there is more that remains undiscovered.” We have since discovered hundreds more Gamaredon-related domains, including known related-clusters, and also new clusters. We have updated our Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) to include these additional domains and cluster observations.

Update June 22: As noted in February, Unit 42 continues to monitor and research Gamaredon infrastructure and malware. Today we are sharing another update to our Gamaredon IoCs, listing infrastructure that we have observed since the previous update.

Full visualization of the techniques observed, relevant courses of action and IoCs related to this Gamaredon report can be found in the Unit 42 ATOM viewer.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protections against the types of threats discussed in this blog by products including Cortex XDR and the WildFire, AutoFocus, Advanced URL Filtering and DNS Security subscription services for the Next-Generation Firewall.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Gamaredon, APTs |

Gamaredon Downloader Infrastructure (Cluster 1)

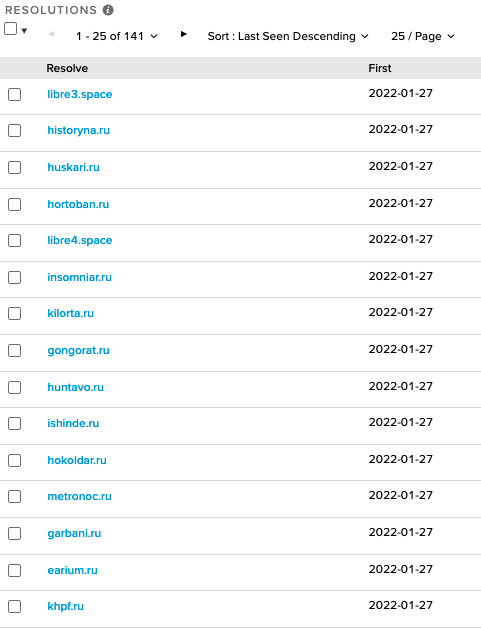

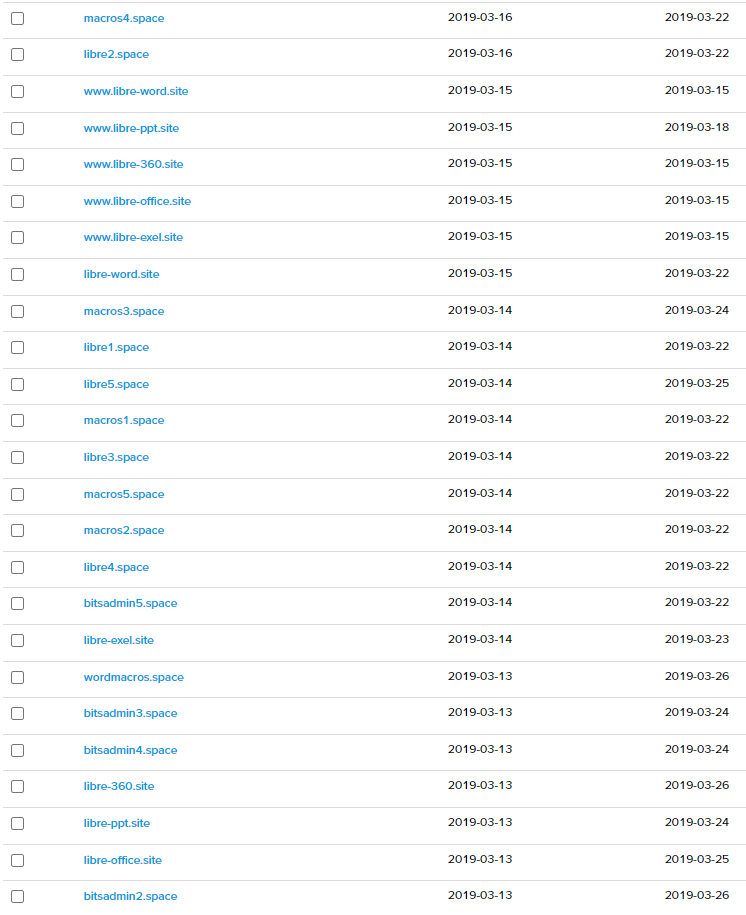

Gamaredon actors pursue an interesting approach when it comes to building and maintaining their infrastructure. Most actors choose to discard domains after their use in a cyber campaign in order to distance themselves from any possible attribution. However, Gamaredon’s approach is unique in that they appear to recycle their domains by consistently rotating them across new infrastructure. A prime example can be seen in the domain libre4[.]space. Evidence of its use in a Gamaredon campaign was flagged by a researcher as far back as 2019. Since then, Cisco Talos and Threatbook have also firmly attributed the domain to Gamaredon. Yet despite public attribution, the domain continues to resolve to new internet protocol (IP) addresses daily.

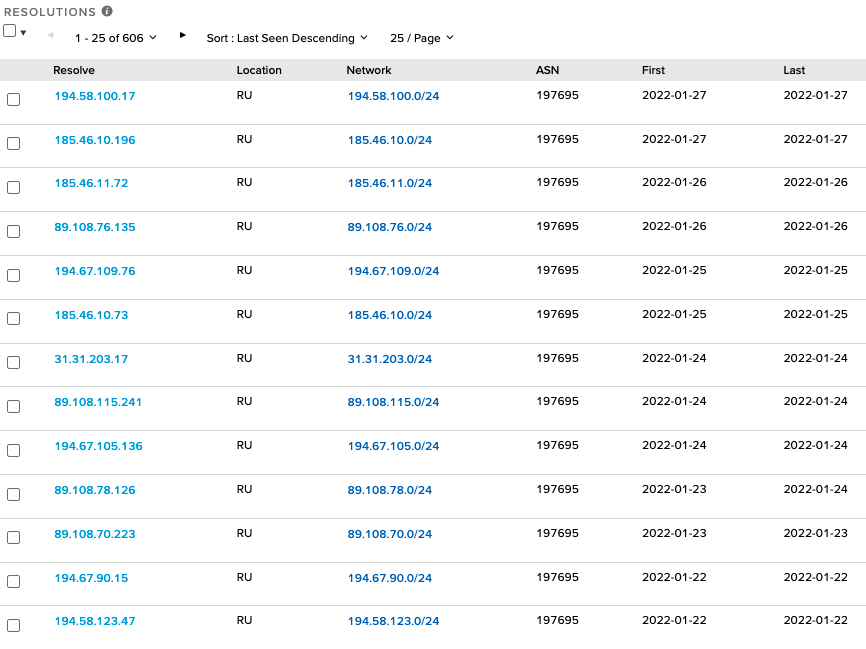

Focusing on the IP addresses linked to these domains over the last 60 days results in the identification of 136 unique IP addresses; interestingly, 131 of these IP addresses are hosted within the autonomous system (AS) 197695 physically located in Russia and operated by the same entity used as the registrar for these domains, reg[.]ru. The total number of IPs translates to the introduction of roughly two new IP addresses every day into Gamaredon’s malicious infrastructure pool. Monitoring this pool, it appears that the actors are activating new domains, using them for a few days, and then adding the domains to a pool of domains that are rotated across various IP infrastructure. This shell game approach affords a degree of obfuscation to attempt to hide from cybersecurity researchers.

For researchers, it becomes difficult to correlate specific payloads to domains and to the IP address that the domain resolved to on the precise day of a phishing campaign. Furthermore, Gamaredon’s technique provides the actors with a degree of control over who can access malicious files hosted on their infrastructure, as a web page’s uniform resource locator (URL) file path embedded in a downloader only works for a finite period of time. Once the domains are rotated to a new IP address, requests for the URL file paths will result in a “404” file not found error for anyone attempting to study the malware.

Cluster 1 History

While focusing on current downloader infrastructure, we were able to trace the longevity of this cluster back to an origin in 2018. Certain “marker” domains, such as the aforementioned libre4[.]space, are still active today and also traced back to March 2019 with apparently consistent ownership. On the same date range in March 2019, a cluster of domains was observed on 185.158.114[.]107 with thematically linked naming – several of which are still active in this cluster today.

Initial Downloaders

Searching for samples connecting to Gamaredon infrastructure across public and private malware repositories resulted in the identification of 17 samples over the past three months. The majority of these files were either shared by entities in Ukraine or contained Ukrainian filenames.

| Filename | Translation |

| Максим.docx | Maksim.docx |

| ПІДОЗРА РЯЗАНЦЕВА.docx | RAZANTSEV IS SUSPICIOUS.docx |

| протокол допиту.docx | interrogation protocol.docx |

| ТЕЛЕГРАММА.docx | TELEGRAM.docx |

| 2_Пам’ятка_про_процесуальні_права_та_обов’язки_потерпілого.docx | 2_Memorial_about_processal_rights_and_obligations_of_the_ Victim.docx |

| 2_Porjadok_do_nakazu_111_vid_13.04.2017.docx | 2_Procedure_to_order_111_from_13.04.2017.docx |

| висновок тимошечкин.docx | conclusion Timoshechkin.docx |

| Звіт на ДМС за червень 2021 (Автосохраненный).doc | Report on the LCA for June 2021 (Autosaved) .doc |

| висновок Кличко.docx | Klitschko's conclusion.docx |

| Обвинувальний акт ГЕРМАН та ін.docx | Indictment GERMAN et al.docx |

| супровід 1-СЛ 10 місяців.doc | support 1-SL 10 months.doc |

Table 1. Recently observed downloader filenames.

An analysis of these files found that they all leveraged a remote template injection technique that allows the documents to pull down the malicious code once they are opened. This allows the attacker to have control over what content is sent back to the victim in an otherwise benign document. Recent examples of the remote template “dot” file URLs these documents use include the following:

http://bigger96.allow.endanger.hokoldar[.]ru/[Redacted]/globe/endanger/lovers.cam

http://classroom14.nay.sour.reapart[.]ru/[Redacted]/bid/sour/glitter.kdp

http://priest.elitoras[.]ru/[Redacted]/pretend/pretend/principal.dot

http://although.coferto[.]ru/[Redacted]/amazing.dot

http://source68.alternate.vadilops[.]ru/[Redacted]/clamp/interdependent.cbl

Many of the files hosted on the Gamaredon infrastructure are labeled with abstract extensions such as .cam, .cdl, .kdp and others. We believe this is an intentional effort by the actor to reduce exposure and detection of these files by antivirus and URL scanning services.

Taking a deeper look at the top two, hokoldar[.]ru and reapart[.]ru, provides unique insights into two recent phishing campaigns. Beginning with the first domain, passive DNS data shows that the domain first resolved to an IP address that was shared with other Gamaredon domains on Jan. 4. Figure 2 above shows that hokoldar[.]ru continued to share an IP address with libre4[.]space on Jan. 27, once again associating it with the Gamaredon infrastructure pool. In that short window, on Jan. 19, we observed a targeted phishing attempt against a Western government entity operating in Ukraine.

In this attempt, rather than emailing the downloader directly to their target, the actors instead leveraged a job search and employment service within Ukraine. In doing so, the actors searched for an active job posting, uploaded their downloader as a resume and submitted it through the job search platform to a Western government entity. Given the steps and precision delivery involved in this campaign, it appears this may have been a specific, deliberate attempt by Gamaredon to compromise this Western government organization.

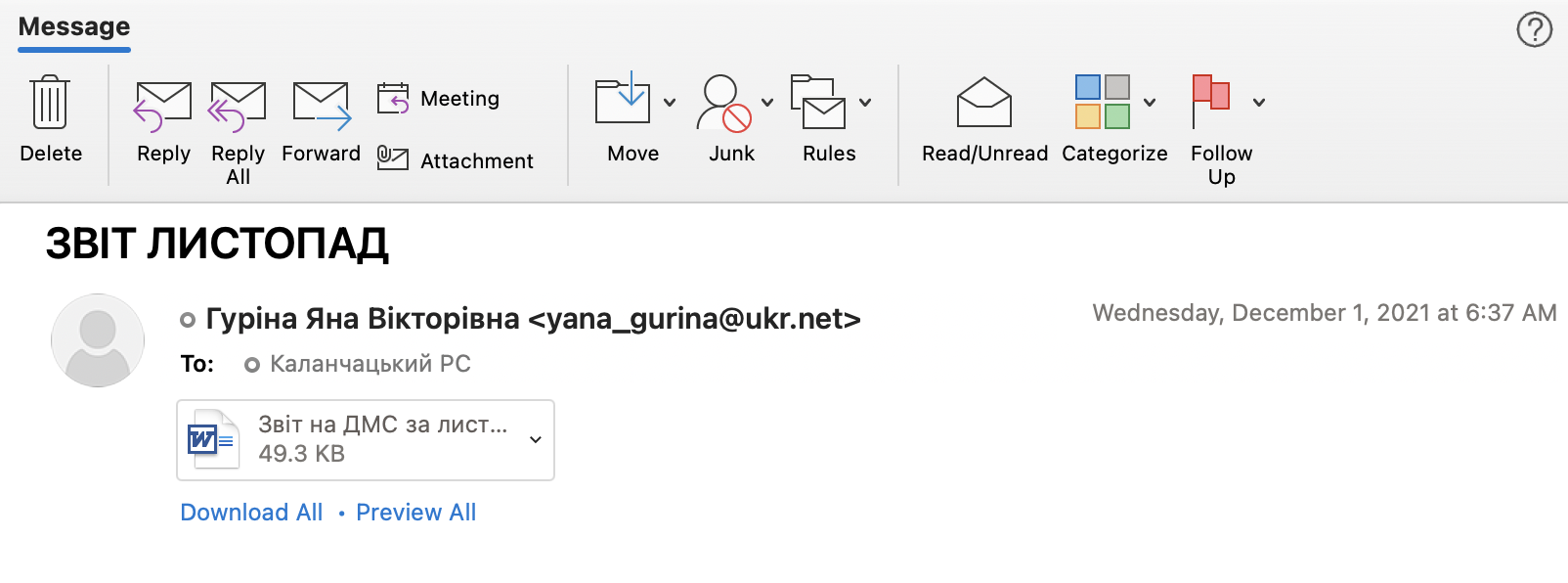

Expanding beyond this recent case, we also discovered public evidence of a Gamaredon campaign targeting the State Migration Service of Ukraine. On Dec. 1, an email was sent from yana_gurina@ukr[.]net to 6524@dmsu[.]gov.ua. The subject of the email was “NOVEMBER REPORT” and attached to the email was a file called “Report on the LCA for June 2021(Autosaved).doc.” When opened, this Word document calls out to reapart[.]ru. From there, it downloads and then executes a malicious remote Word Document Template file named glitter.kdp.

SSL Pivot to Additional Infrastructure and Samples

While conducting historical research on the infrastructure in cluster 1, we discovered a self-signed certificate associated with cluster 1 IP address 92.242.62[.]96:

Serial: 373890427866944398020500009522040110750114845760

SHA1: 62478d7653e3f5ce79effaf7e69c9cf3c28edf0c

Issued: 2021-01-27

Expires: 2031-01-25

Common name: ip45-159-200-109.crelcom[.]ru

Although the IP Address WHOIS record for Crelcom LLC is registered to an address in Moscow, the technical admin listed for the netblock containing the IP address is registered to an address in Simferopol, Crimea. We further trace the apparent origins of Crelcom back to Simferopol, Crimea, as well.

This certificate relates to 79 IP addresses:

- The common-name IP address - no Gamaredon domains

- One IP address links to cluster 1 above (92.242.62[.]96)

- 76 IP addresses link to another distinct collection of domains – “cluster 2”

- 1 IP address led us to another distinct cluster, “cluster 3” (194.67.116[.]67)

We find almost no overlap of IP addresses between these separate clusters.

File Stealer (Cluster 2)

Of the 76 IP addresses we associate with cluster 2, 70 of them have confirmed links to C2 domains associated with a variant of Gamaredon’s file stealer tool. Within the last three months, we have identified 23 samples of this malware, twelve of which appear to have been shared by entities in Ukraine. The C2 domains in those samples include:

| Domain | First Seen |

| jolotras[.]ru | 12/16/2021 |

| moolin[.]ru | 10/11/2021 |

| naniga[.]ru | 9/2/2021 |

| nonimak[.]ru | 9/2/2021 |

| bokuwai[.]ru | 9/2/2021 |

| krashand[.]ru | 6/17/2021 |

| gorigan[.]ru | 5/25/2021 |

Table 3. Recent file stealer C2 domains.

As you can see, some of these domains were established months ago, yet despite their age, they continue to enjoy benign reputations. For example, only five out of 93 vendors consider the domain krashand[.]ru to be malicious on VirusTotal.

| Subdomains |

| 637753576301692900[.]jolotras.ru |

| 637753623005957947[.]jolotras[.]ru |

| 637755024217842817.jolotras[.]ru |

| a.nonimak[.]ru |

| aaaa.nonimak[.]ru |

| aaaaa.nonimak[.]ru |

| aaaaaa.nonimak[.]ru |

| 0enhzs.moolin[.]ru |

| 0ivrlzyk.moolin[.]ru |

| 0nxfri.moolin[.]ru |

Table 4. Subdomain naming for file stealer infrastructure.

In mapping these domains to their corresponding C2 infrastructure, we discovered that the domains overlap in terms of the IP addresses they point to. This allowed us to identify the following active infrastructure:

| IP Address | First Seen |

| 194.58.92[.]102 | 1/14/2022 |

| 37.140.199[.]20 | 1/10/2022 |

| 194.67.109[.]164 | 12/16/2021 |

| 89.108.98[.]125 | 12/26/2021 |

| 185.46.10[.]143 | 12/15/2021 |

| 89.108.64[.]88 | 10/29/2021 |

Table 5. Recent file stealer IP infrastructure.

Of note, all of the file stealer infrastructure appears to be hosted within AS197695, the same AS highlighted earlier. Historically, we have seen the C2 domains point to various autonomous systems (AS) globally. However, as of early November, it appears that the actors have consolidated all of their file stealer infrastructure within Russian ASs – predominantly this single AS.

In mapping the patterns involved in the use of this infrastructure, we found that the domains are rotated across IP addresses in a manner similar to the downloader infrastructure discussed previously. A malicious domain may point to one of the C2 server IP addresses today while pointing to a different address tomorrow. This adds a degree of complexity and obfuscation that makes it challenging for network defenders to identify and remove the malware from infected networks. The discovery of a C2 domain in network logs thus requires defenders to search through their network traffic for the full collection of IP addresses that the malicious domain has resolved to over time. As an example, moolin[.]ru has pointed to 11 IP addresses since early October, rotating to a new IP every few days.

| IP Address | Country | AS | First Seen | Last Seen |

| 194.67.109[.]164 | RU | 197695 | 2021-12-28 | 2022-01-27 |

| 185.46.10[.]143 | RU | 197695 | 2021-12-16 | 2021-12-26 |

| 212.109.199[.]204 | RU | 29182 | 2021-12-15 | 2021-12-15 |

| 80.78.241[.]253 | RU | 197695 | 2021-11-19 | 2021-12-14 |

| 89.108.78[.]82 | RU | 197695 | 2021-11-16 | 2021-11-18 |

| 194.180.174[.]46 | MD | 39798 | 2021-11-15 | 2021-11-15 |

| 70.34.198[.]226 | SE | 20473 | 2021-10-14 | 2021-10-30 |

| 104.238.189[.]186 | FR | 20473 | 2021-10-13 | 2021-10-14 |

| 95.179.221[.]147 | FR | 20473 | 2021-10-13 | 2021-10-13 |

| 176.118.165[.]76 | RU | 43830 | 2021-10-12 | 2021-10-13 |

Table 6. Recent file stealer IP infrastructure

Shifting focus to the malware itself, file stealer samples connect to their C2 infrastructure in a unique manner. Rather than connecting directly to a C2 domain, the malware performs a DNS lookup to convert the domain to an IP address. Once complete, it establishes an HTTPS connection directly to the IP address. For example:

C2 Domain: moolin[.]ru

C2 IP Address: 194.67.109[.]164

C2 Comms: https://194.67.109[.]164/zB6OZj6F0zYfSQ

This technique of creating distance between the domain and the physical C2 infrastructure seems to be an attempt to bypass URL filtering:

- The domain itself is only used in an initial DNS request to resolve the C2 server IP address – no actual connection is attempted using the domain name.

- Identification and blocking of a domain doesn’t impact existing compromises as the malware will continue to communicate directly with the C2 server using the IP address – even if the domain is subsequently deleted or rotated to a new IP – as long as the malware continues to run.

One recent file stealer sample we analyzed (SHA256: f211e0eb49990edbb5de2bcf2f573ea6a0b6f3549e772fd16bf7cc214d924824) was found to be a .NET binary that had been obfuscated to make analysis more difficult. The first thing that jumps out when reviewing these files are their sizes. This particular file clocks in at over 136 MB in size, but we observed files going all the way up to 200 MB and beyond. It is possible that this is an attempt to circumvent automated sandbox analysis, which usually avoids scanning such large files. It may also simply be a byproduct of the obfuscation tools being used. Whatever the reason for the large file size, it comes at a price to the attacker, as executables of this size stick out upon review. Transmitting a file this large to a victim becomes a much more challenging task.

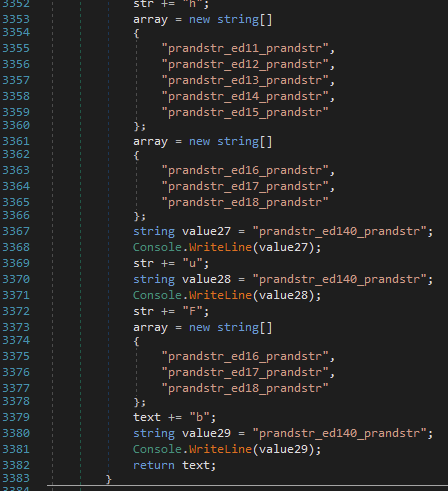

The obfuscation within this sample is relatively simple and mainly relies upon defining arrays and concatenating strings of single characters in high volume over hundreds of lines to try to hide the construction of the actual string within the noise.

It begins by checking for the existence of the Mutex Global\lCHBaUZcohRgQcOfdIFaf, which, if present, implies the malware is already running and will cause the file stealer to exit. Next, it will create the folder C:\Users\%USER%\AppData\Local\TEMP\ModeAuto\icons, wherein screenshots that are taken every minute will be stored and then transmitted to the C2 server with the name format YYYY-MM-DD-HH-MM.jpg.

To identify the IP address of the C2 server, the file stealer will generate a random string of alphanumeric characters between eight and 23 characters long, such as 9lGo990cNmjxzWrDykSJbV.jolotras[.]ru.

As mentioned previously, once the file stealer retrieves the IP address for this domain, it will no longer use the domain name. Instead, all communications will be direct with the IP address.

During execution, it will search all fixed and network drives attached to the computer for the following extensions:

.doc

.docx

.xls

.rtf

.odt

.txt

.jpg

.pdf

.ps1

When it has a list of files on the system, it begins to create a string for each that contains the path of the file, the size of the file and the last time the file was written to, similar to the example below:

C:\cygwin\usr\share\doc\bzip2\manual.pdf2569055/21/2011 3:17:02 PM

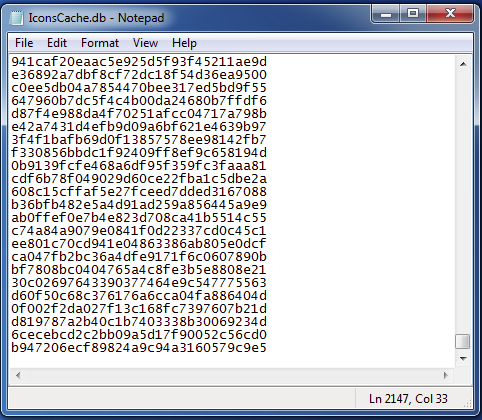

The file stealer takes this string and generates an MD5 hash of it, resulting in the following output for this example:

FB-17-F1-34-F4-22-9B-B4-49-0F-6E-3E-45-E3-C9-FA

Next, it removes the hyphens from the hash and converts all uppercase letters to lowercase. These MD5 hashes are then saved into the file C:\Users\%USER%\AppData\Local\IconsCache.db. The naming of this file is another attempt to hide in plain sight next to the legitimate IconCache.db.

The malware uses this database to track unique files.

The malware will then generate a URL path with alphanumeric characters for its C2 communication, using the DNS-IP technique illustrated previously with the moolin[.]ru domain example:

https://194.67.109[.]164/zB6OZj6F0zYfSQ

Below is the full list of domains currently resolving to cluster 2 IP addresses:

| Domain | Registered |

| jolotras[.]ru | 12/16/2021 |

| moolin[.]ru | 10/11/2021 |

| bokuwai[.]ru | 9/2/2021 |

| naniga[.]ru | 9/2/2021 |

| nonimak[.]ru | 9/2/2021 |

| bilargo[.]ru | 7/23/2021 |

| krashand[.]ru | 6/17/2021 |

| firtabo[.]ru | 5/28/2021 |

| gorigan[.]ru | 5/25/2021 |

| firasto[.]ru | 5/21/2021 |

| myces[.]ru | 2/24/2021 |

| teroba[.]ru | 2/24/2021 |

| bacilluse[.]ru | 2/15/2021 |

| circulas[.]ru | 2/15/2021 |

| megatos[.]ru | 2/15/2021 |

| phymateus[.]ru | 2/15/2021 |

| cerambycidae[.]ru | 1/22/2021 |

| coleopteras[.]ru | 1/22/2021 |

| danainae[.]ru | 1/22/2021 |

Table 7. All cluster 2 domains.

Pteranodon (Cluster 3)

The single remaining IP address related to the SSL certificate was not related to either cluster 1 or cluster 2, and instead led us to a third, distinct cluster of domains.

This final cluster appears to serve as the C2 infrastructure for a custom remote administration tool called Pteranodon. Gamaredon has used, maintained and updated development of this code for years. Its code contains anti-detection functions specifically designed to identify sandbox environments in order to thwart antivirus detection attempts. It is capable of downloading and executing files, capturing screenshots and executing arbitrary commands on compromised systems.

Over the last three months, we have identified 33 samples of Pteranodon. These samples are commonly named 7ZSfxMod_x86.exe. Pivoting across this cluster, we identified the following C2 infrastructure:

| Domain | Registered |

| takak[.]ru | 9/18/2021 |

| rimien[.]ru | 9/18/2021 |

| maizuko[.]ru | 9/2/2021 |

| iruto[.]ru | 9/2/2021 |

| gloritapa[.]ru | 8/5/2021 |

| gortisir[.]ru | 8/5/2021 |

| gortomalo[.]ru | 8/5/2021 |

| langosta[.]ru | 6/25/2021 |

| malgaloda[.]ru | 6/8/2021 |

Table 8. Cluster 3 domains.

We again observe domain reputation aging, as seen in cluster 2.

An interesting naming pattern is seen in cluster 3 – also seen in some cluster 1 host and subdomain names. We see these actors using English words, seemingly grouped by the first two or three letters. For example:

deep-rooted.gloritapa[.]ru

deep-sinking.gloritapa[.]ru

deepwaterman.gloritapa[.]ru

deepnesses.gloritapa[.]ru

deep-lunged.gloritapa[.]ru

deerfood.gortomalo[.]ru

deerbrook.gortomalo[.]ru

despite.gortisir[.]ru

des.gortisir[.]ru

desire.gortisir[.]ru

This pattern differs from those of cluster 2, but has been observed on some cluster 1 (dropper) domains, for example:

alley81.salts.kolorato[.]ru

allied.striman[.]ru

allowance.hazari[.]ru

allowance.telefar[.]ru

ally.midiatr[.]ru

allocate54.previously.bilorotka[.]ru

alluded6.perfect.bilorotka[.]ru

already67.perfection.zanulor[.]ru

already8.perfection.zanulor[.]ru

This pattern is even carried into HTTP POSTs, files and directories created by associated samples:

Example 1:

SHA256: 74cb6c1c644972298471bff286c310e48f6b35c88b5908dbddfa163c85debdee

deerflys.gortomalo[.]ru

C:\Windows\System32\schtasks.exe /CREATE /sc minute /mo 11 /tn "deepmost" /tr "wscript.exe "C:\Users\Public\\deep-naked\deepmost.fly" counteract /create //b /criminal //e:VBScript /cracker counteract " /F

POST /index.eef/deep-water613

Example 2:

SHA256: ffb6d57d789d418ff1beb56111cc167276402a0059872236fa4d46bdfe1c0a13

deer-neck.gortomalo[.]ru

"C:\Windows\System32\schtasks.exe" /CREATE /sc minute /mo 13 /tn "deep-worn" /tr "wscript.exe "C:\Users\Public\\deerberry\deep-worn.tmp" crumb /cupboard //b /cripple //e:VBScript /curse crumb " /F

POST /cache.jar/deerkill523

Because we only see this with some domains, this may be a technique employed by a small group of actors or teams. It suggests a possible link between the cluster 3 samples and those from cluster 1 employing a similar naming system. In contrast, we do not observe cluster 2’s large-number or random-string naming technique employed in any cluster 1 domains.

Conclusion

Gamaredon has been targeting Ukrainian victims for almost a decade. As international tensions surrounding Ukraine remain unresolved, Gamaredon’s operations are likely to continue to focus on Russian interests in the region. This blog serves to highlight the importance of research into adversary infrastructure and malware, as well as community collaboration, in order to detect and defend against nation-state cyberthreats. While we have mapped out three large clusters of currently active Gamaredon infrastructure, we believe there is more that remains undiscovered. Unit 42 remains vigilant in monitoring the evolving situation in Ukraine and continues to actively hunt for indicators to put protections in place to defend our customers anywhere in the world. We encourage all organizations to leverage this research to hunt for and defend against this threat.

Protections and Mitigations

The best defense against this evolving threat group is a security posture that favors prevention. We recommend that organizations implement the following:

- Search network and endpoint logs for any evidence of the indicators of compromise associated with this threat group.

- Ensure cybersecurity solutions are effectively blocking against the active infrastructure IoCs identified above.

- Implement a DNS security solution in order to detect and mitigate DNS requests for known C2 infrastructure.

- Apply additional scrutiny to all network traffic communicating with AS 197695 (Reg[.]ru).

- If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42), EMEA: +31.20.299.3130, APAC: +65.6983.8730, or Japan: +81.50.1790.0200.

For Palo Alto Networks customers, our products and services provide the following coverage associated with this campaign:

Cortex XDR protects endpoints from the malware techniques described in this blog.

WildFire cloud-based threat analysis service accurately identifies the malware described in this blog as malicious.

Advanced URL Filtering and DNS Security identify all phishing and malware domains associated with this group as malicious.

Users of AutoFocus contextual threat intelligence service can view malware associated with these attacks using the Gamaredon Group tag.

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Indicators of Compromise

A list of the domains, IP addresses and malware hashes is available on the Unit 42 GitHub.

Additional IoCs shared in a Feb. 16 update to this report are also available.

On June 22, we shared additional Gamaredon IoCs.

Additional Resources

The Gamaredon Group Toolset Evolution – Unit 42, Palo Alto Networks

Threat Brief: Ongoing Russia and Ukraine Cyber Conflict – Unit 42, Palo Alto Networks

Technical Report on Armageddon / Gamaredon – Security Service of Ukraine

Tale of Gamaredon Infection – CERT-EE / Estonian Information System Authority

Updated November 30, 2022, at 11:25 a.m. PT.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42