Executive Summary

We are attributing an ongoing smishing (phishing via text message) campaign of fraudulent toll violation and package misdelivery notices to a group widely known as the Smishing Triad. Our analysis indicates this campaign is a significantly more extensive and complex threat than previously reported. Attackers have impersonated international services across a wide array of critical sectors.

The attackers have targeted U.S. residents in this campaign since April 2024. The threat actor is evolving their tactics by expanding their reach globally, improving the social engineering tactics used in smishing for delivery.

The threat actor is also expanding the range of services they impersonate to include many international services in critical sectors, such as:

- Banking

- Cryptocurrency platforms

- E-commerce platforms

- Healthcare

- Law enforcement

- Social media

The campaign is highly decentralized, lacking a single point of control, and uses a large number of domains and a diverse set of hosting infrastructure. This is advantageous for the attackers as churning through thousands of domains weekly makes detection more difficult.

Using our intelligence framework, we have identified over 194,000 malicious domains linked to this operation since Jan. 1, 2024. Although these domains are registered through a Hong Kong-based registrar and use Chinese nameservers, the attack infrastructure is primarily hosted on popular U.S. cloud services.

This campaign uses SMS messages for social engineering to create a sense of urgency and prompt victims into immediate action. The campaign's global scale, complex infrastructure and realistic phishing pages strongly suggest that it is powered by a large, well-resourced phishing-as-a-service (PhaaS) operation. This poses a widespread threat to individuals globally. These phishing pages aim to collect sensitive information such as National Identification Numbers (such as Social Security numbers), home addresses, payment details and login credentials.

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from this activity through the following products and services:

If you think you might have been compromised or have an urgent matter, contact the Unit 42 Incident Response team.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Phishing, SMS |

Technical Analysis of the Extended Smishing Triad Campaign

Earlier this year, we released timely threat intelligence social posts that reported our discovery of more than 10,000 domains involved in smishing scams. Subsequently, we found and blocked over 91,500 domains involved in the same scam. Since publishing those threat intelligence posts, we have continued to track and analyze the threat actors and domains behind these smishing scams.

Security vendor Resecurity attributes these attacks to the Smishing Triad, reporting that the group shared phishing kits on Telegram and other services. This finding is corroborated by follow-up reports by Silent Push. However, our analysis reveals that the campaign's scope is far broader and evolves faster than previously known.

Many indicators suggest that the campaign is constantly evolving. A Fortinet article highlighted the fact that the threat actors used email-to-SMS features. This article noted that arbitrary email addresses can be used to send messages through iMessage. However, we have observed that more recent smishing messages have started to use phone numbers to send them.

Many of these messages are received from phone numbers beginning with the international country code for the Philippines (+63). However, there has been an increasing number of messages in this campaign received from U.S. phone numbers (+1) as well.

Tracking all domains in this campaign is challenging due to its decentralized nature. The attack domains are short-lived and constantly churned, with thousands registered daily. The rapidly evolving campaign highlights that tracking root domains using just lexical patterns is not enough.

We have developed a multi-faceted intelligence framework to track this campaign. It synthesizes data from the following sources:

- WHOIS and passive DNS (pDNS) reputation metrics

- Evolving domain patterns

- Visual clustering of screenshots

- Graph-based infrastructure analysis

Using our multi-faceted intelligence framework, we found a total of 194,345 fully qualified domain names (FQDNs) across 136,933 root domains associated with this campaign. These root domains were registered on or after Jan. 1, 2024.

The majority of these domains are registered through Dominet (HK) Limited, a Hong Kong-based registrar and use Chinese nameservers. Although the domain registration and DNS infrastructure originate in China, the attacking infrastructure (the hosting IP addresses) is concentrated in the U.S., particularly within popular cloud services.

We find that the domains in this campaign impersonate global services in many sectors, including:

- Critical services: Banking, healthcare and law enforcement (e.g., multi-national financial services and investment companies, police forces from cities in the Middle East)

- Widely used services: E-commerce, social media, online gaming and cryptocurrency exchanges (e.g., several Russia-based e-commerce markets and cryptocurrency exchanges)

- Previously reported services: Tolls and global state-owned mail and package delivery services extending beyond the U.S. (e.g., Israel, Canada, France, Germany, Ireland, Australia, Argentina)

Attackers craft SMS messages to deliver these URLs. These are highly tailored to the victims to compel immediate action. Using social engineering techniques creates a sense of urgency. By employing targeted personal information and incorporating technical or legal jargon they can appear more legitimate. These things combined with the scope of services imitated suggests that a large PhaaS operation is behind this campaign.

Underground Phishing-as-a-Service Ecosystem

In this section, we discuss the underground PhaaS ecosystem and investigate the Smishing Triad Telegram channel. Over the past six months, the channel has evolved from a dedicated phishing kit marketplace into a highly active community that gathers diverse threat actors within the PhaaS ecosystem.

Figure 1 shows chat records from different participants within the channel. Most posts are advertising various underground services such as domain registration, data sales and message delivery. Highlighting the intense competition within this ecosystem, multiple threat actors compete to offer the same services, particularly Rich Communication Services and Instant Message delivery (RCS/IM).

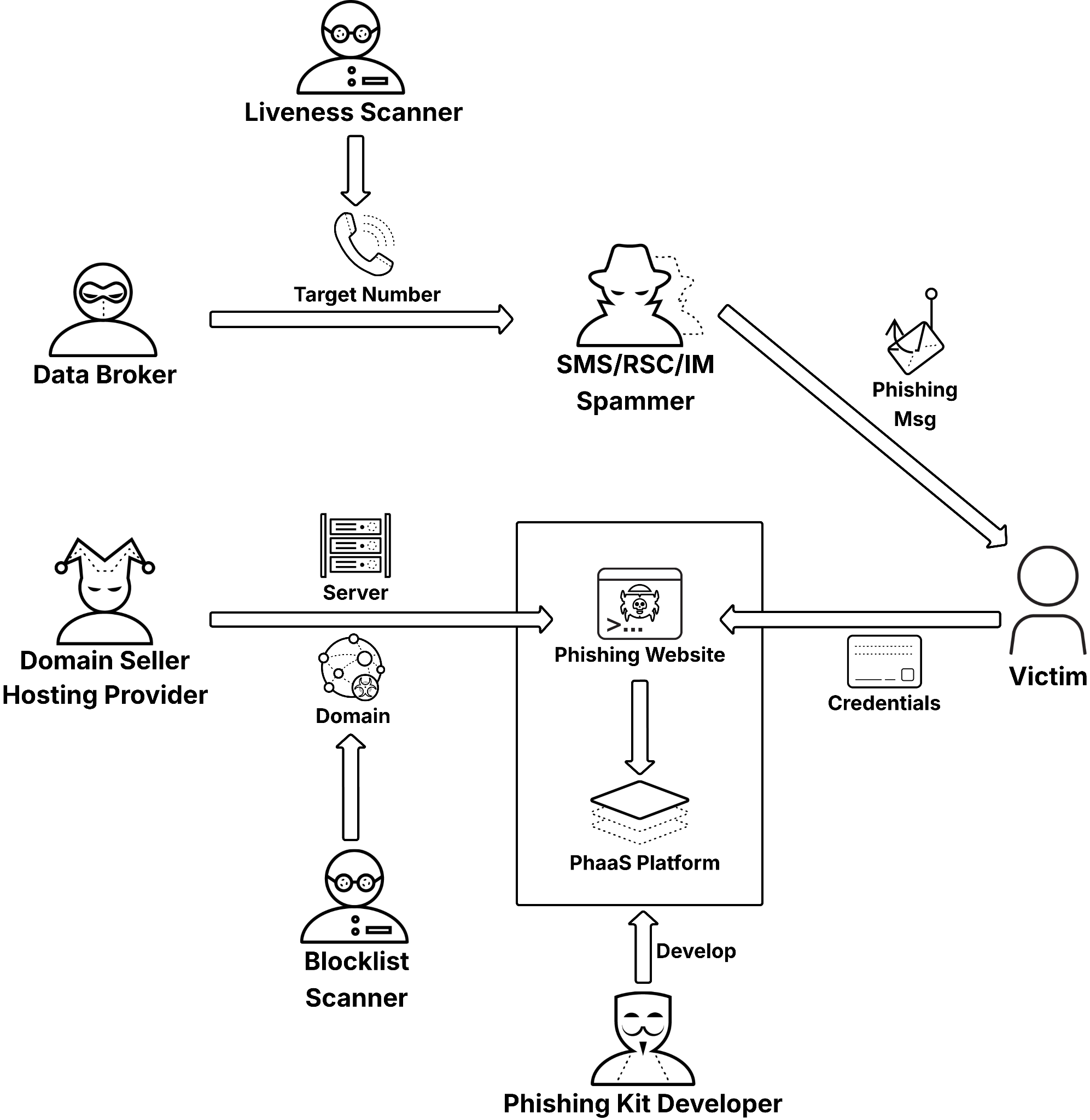

Figure 2 illustrates below the different roles active in the Smishing Triad Telegram channel and their interactions.

Threat actors specialize in different stages of the smishing supply chain, enabling them to launch attacks more efficiently and scalably:

- Upstream

- Data broker: Sells target phone numbers

- Domain seller: Registers disposable domains for hosting phishing websites

- Hosting provider: Provides servers to run phishing backends

- Midstream

- Phishing kit developer: Builds phishing websites (frontend and backend) and maintains the PhaaS platform, including dashboards for harvesting and managing stolen credentials

- Downstream

- SMS/RCS/IM spammer: Delivers phishing messages at scale to direct victims to phishing websites

- Support

- Liveness scanner: Verifies which target phone numbers are valid and active

- Blocklist scanner: Checks the phishing domains against blocklists to trigger asset rotations

Domains Involved in the Campaign

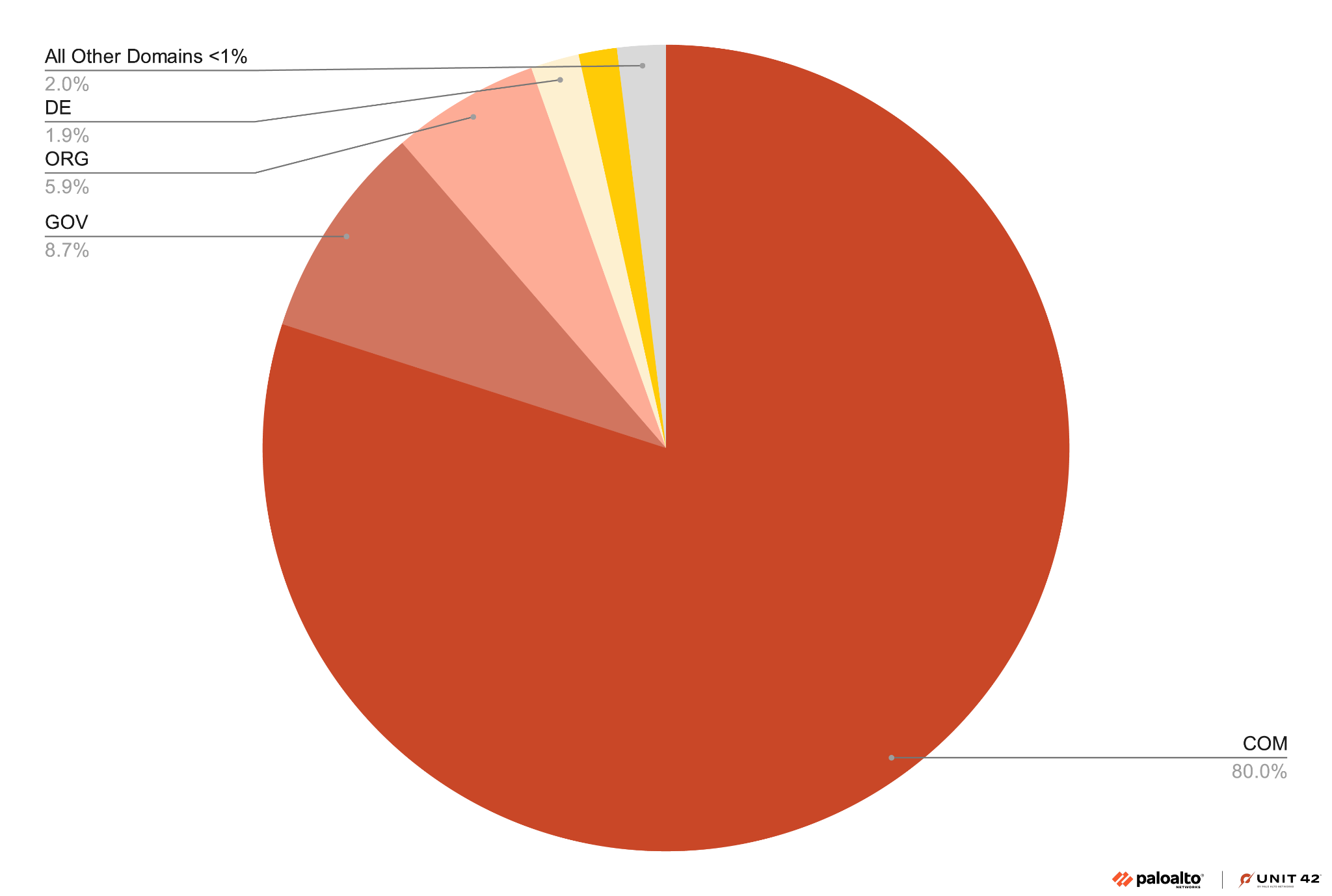

A majority of the root domains involved in this campaign were created with a hyphenated series of strings followed by a top-level domain (TLD) (e.g., [string1]-[string2].[TLD]). In this section, we describe the part before the first hyphen as a prefix. In conjunction with a well-known subdomain, these prefixes could potentially trick victims. For instance, a casual inspection of the domain irs.gov-addpayment[.]info could trick people into thinking they are navigating to irs[.]gov.

Figure 3 shows the most popular prefixes of domain names used in the 136,933 root domains we found in this campaign.

While these domains are registered through various registrars, a significant majority (68.06% or 93,197) of the root domains are registered under Dominet (HK) Limited, a registrar based in Hong Kong. The next most popular registrars are Namesilo with 11.85% (16,227) and Gname with 7.94% (10,873) of the root domains.

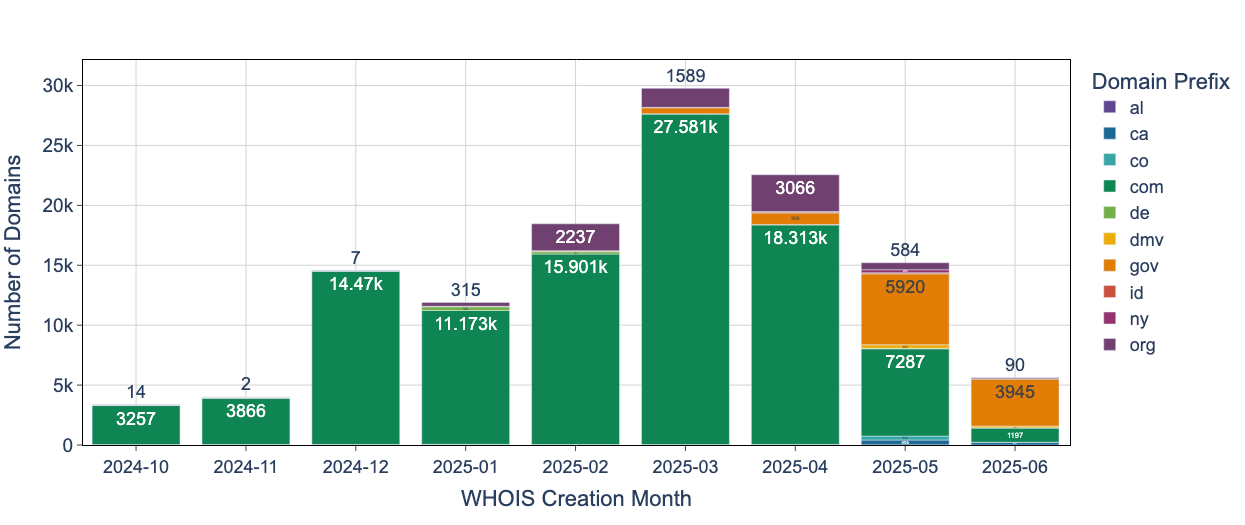

Domain Registration Trends

The WHOIS creation dates shown in Figure 4 reveal an interesting shift. We have picked the top 10 most popular domain prefixes in this campaign. The domains with the prefix com- were the most commonly registered in this campaign until May 2025. However, in the past three months, we observed a significant increase in the registration of gov- domains relative to com- domains. This indicates that the campaign is evolving to fit the types of services it impersonates.

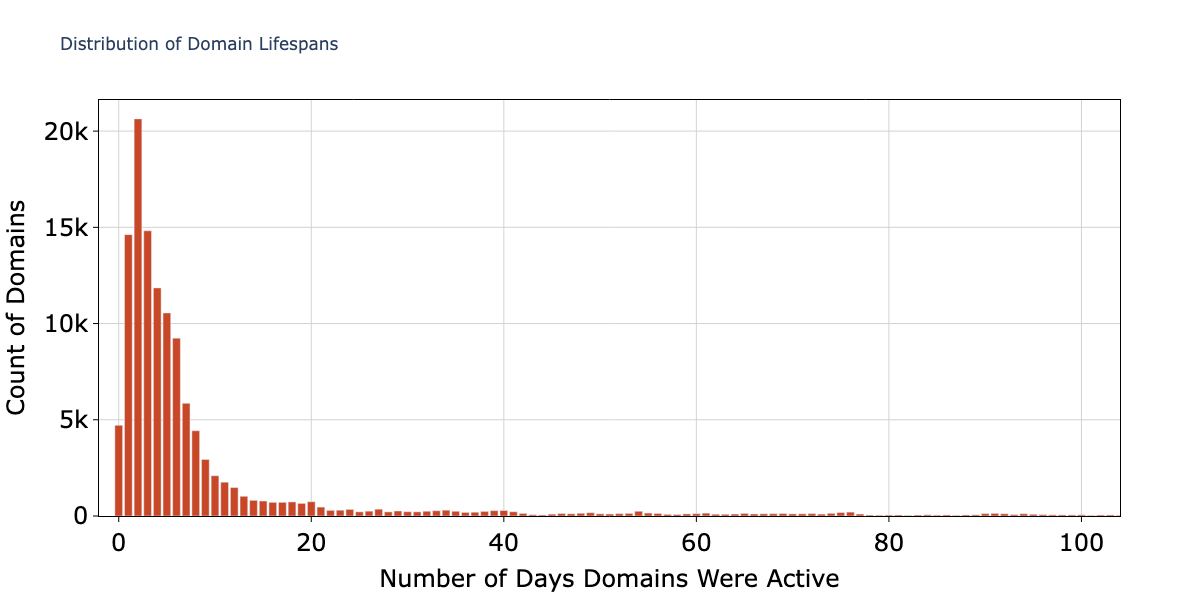

Domain Lifetimes

We also evaluated the lifetime of the domains used in this campaign using pDNS data. A domain's lifetime is the duration between its earliest “first seen” and latest “last seen” timestamps.

As detailed in Figure 5, 39,964 (29.19%) domains were active for two days or less. We saw that 71.3% of these domains were active for less than a week and 82.6% had a lifespan of two weeks or less.

Less than 6% of domains remain active beyond the first three months of their registration. This rapid churn clearly demonstrates that the campaign's strategy relies on a continuous cycle of newly registered domains to evade detection.

Network Infrastructure

As previously mentioned, the domains involved in these campaigns are highly decentralized. In this section, we investigate the network infrastructure of the campaign.

DNS Infrastructure

The 194,345 FQDNs in this campaign resolve to a large and diverse set of approximately 43,494 unique IP addresses. The campaign uses a majority of U.S. IP addresses hosted on Autonomous System AS13335, particularly within the 104.21.0[.]0/16 subnet.

In contrast, the nameserver infrastructure is more concentrated, with only 837 unique nameserver root domains. A large majority of the FQDNs use just two providers: AliDNS (45.6%) and Cloudflare (34.6%). This centralization suggests that while the campaign's web hosting is widely distributed, its DNS management is consolidated under a few key services.

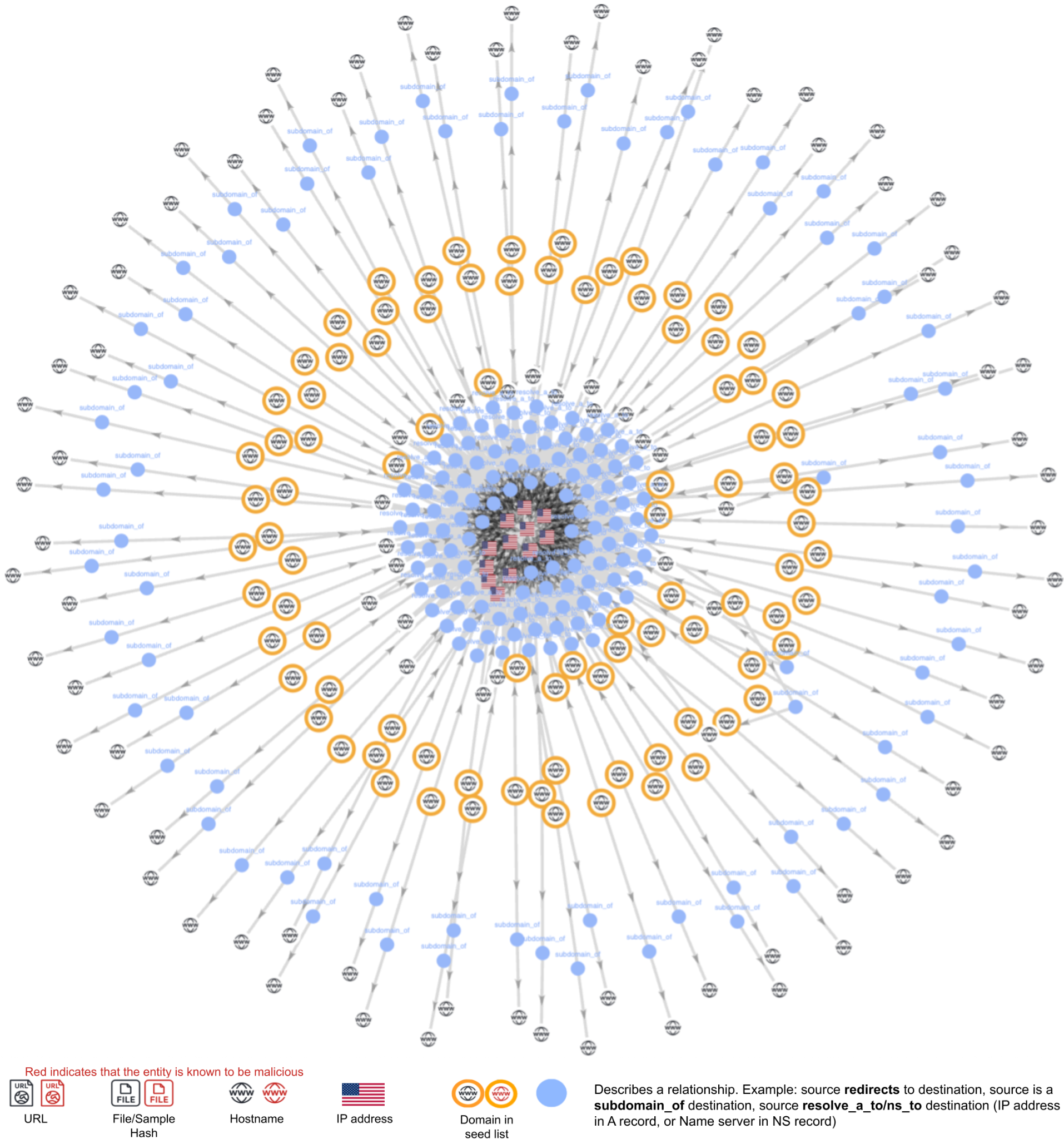

Campaign Infrastructure Graph

In Figure 6, we present an example graph depicting this campaign. We see that there are 90 different root domains pointing to a set of IP addresses in the 104.21.0[.]0/16 subnet belonging to AS13335. There are several such localized clusters for each IP address and nameserver.

We present examples of domains that masquerade as different types of services in the Impersonated Brands and Services section.

Geolocation of the Attack Domains Infrastructure

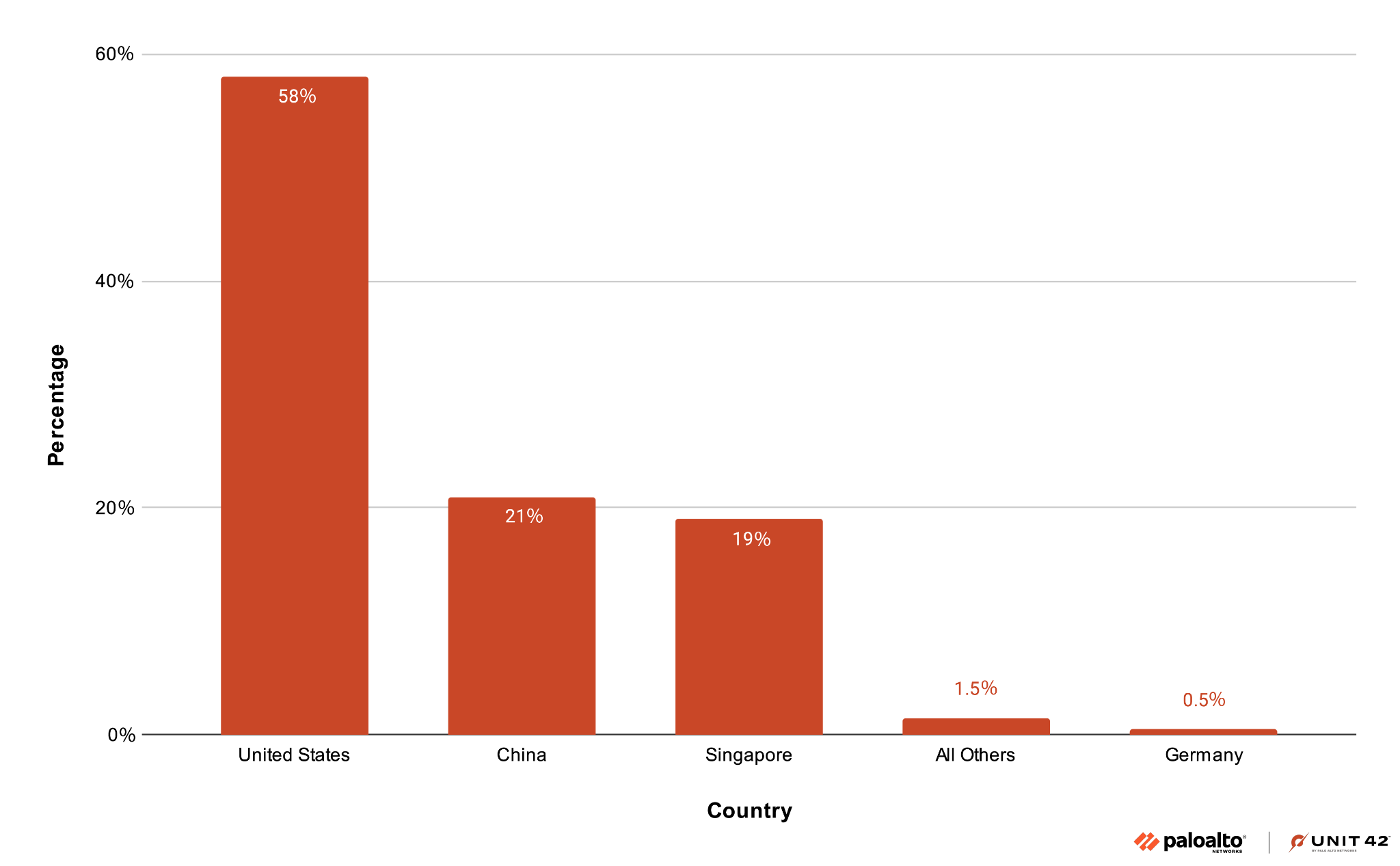

The attack domains are hosted on different IP addresses that are geolocated to various countries. To identify the domains generating the most traffic, we analyzed the distribution of pDNS queries to find the DNS query volume for all domains in the campaign.

We aggregated the number of DNS responses per domain and geolocated the IP addresses in these responses. Queries to domains located in the U.S. account for more than half the volume of queries, as shown in Figure 7. The attack infrastructure for domains generating the largest volume of traffic were located in the U.S., followed by China and Singapore.

Impersonated Brands and Services

A large portion of the attack infrastructure we saw was based in the U.S., and the impersonated services reflected this. However, we also identified attackers impersonating services in other countries.

Large U.S. Focus

The campaign targets individuals. It sends messages that masquerade as coming from various commercial organizations as well as state and U.S. government offices, such as:

- Commercial and state-owned mail and package delivery services

- State vehicles and licensing agencies

- State and federal tax services or agencies

We also found mentions of U.S. state names and their two-letter abbreviations in the FQDNs.

Global Brands and Services

- Critical services: This campaign often includes messages that mimic those that could come from critical services such as mail, toll payment services, law enforcement and banking in several countries:

- The U.S. (banking, mail and delivery, tolls)

- Germany (mail and delivery services, investment banks and savings banks)

- United Arab Emirates (police forces belonging to multiple cities)

- The UK (state-owned services)

- Malaysia, Mexico (banks)

- Argentina, Australia, Canada, France, Ireland, Israel, Russia (electronic tolls, as well as mail and delivery services).

- General services: The campaign involves impersonating messages from many general services such as:

- Carpooling applications

- Online platforms for home-sharing and hospitality services

- Popular social media sites

- Typosquatting: We have observed several FQDNs used in this campaign that are typosquatting popular services, including financial technology applications and personal cloud services

- E-commerce and online payment platforms: This campaign also impersonates several large e-commerce platforms in:

- Russia

- Poland

- Lithuania

- Other countries internationally

- Cryptocurrency exchanges: We found that the campaign also impersonates cryptocurrency exchanges, wallet and Web3 platforms

- Gaming-related: We have found FQDNs used in this campaign relating to online games and fake marketplaces for in-game skins

What Content Is Being Hosted?

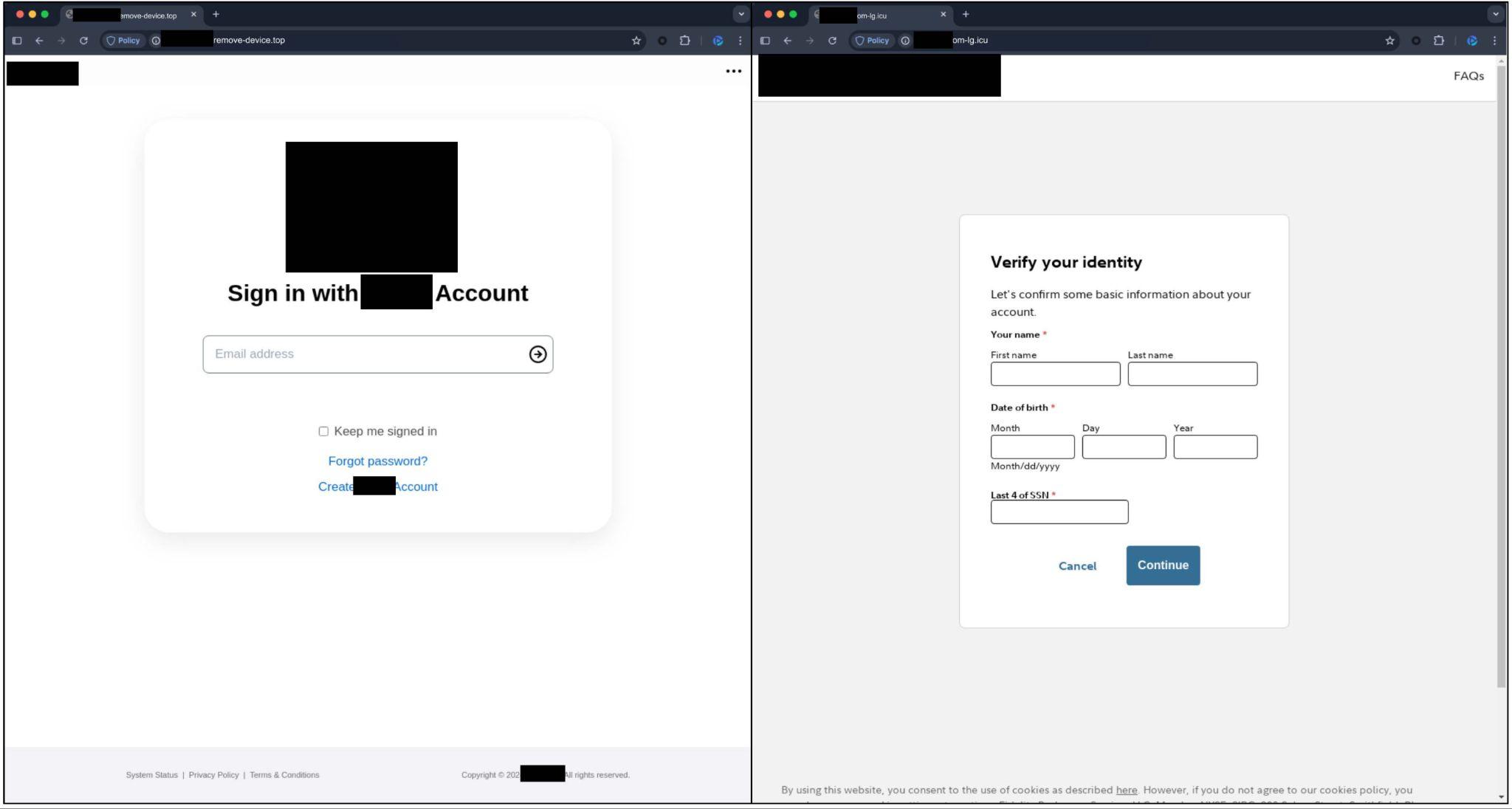

Phishing Impersonating Banking and Popular Services

The most common landing page we observed contained phishing content impersonating the service indicated by the FQDN. Figure 8 presents examples of phishing pages designed to resemble login and identity verification for a consumer electronics company (5,078 FQDNs) and a significant financial services firm (769 FQDNs). These are potentially aimed at extracting victims’ login information and other sensitive information such as social security numbers.

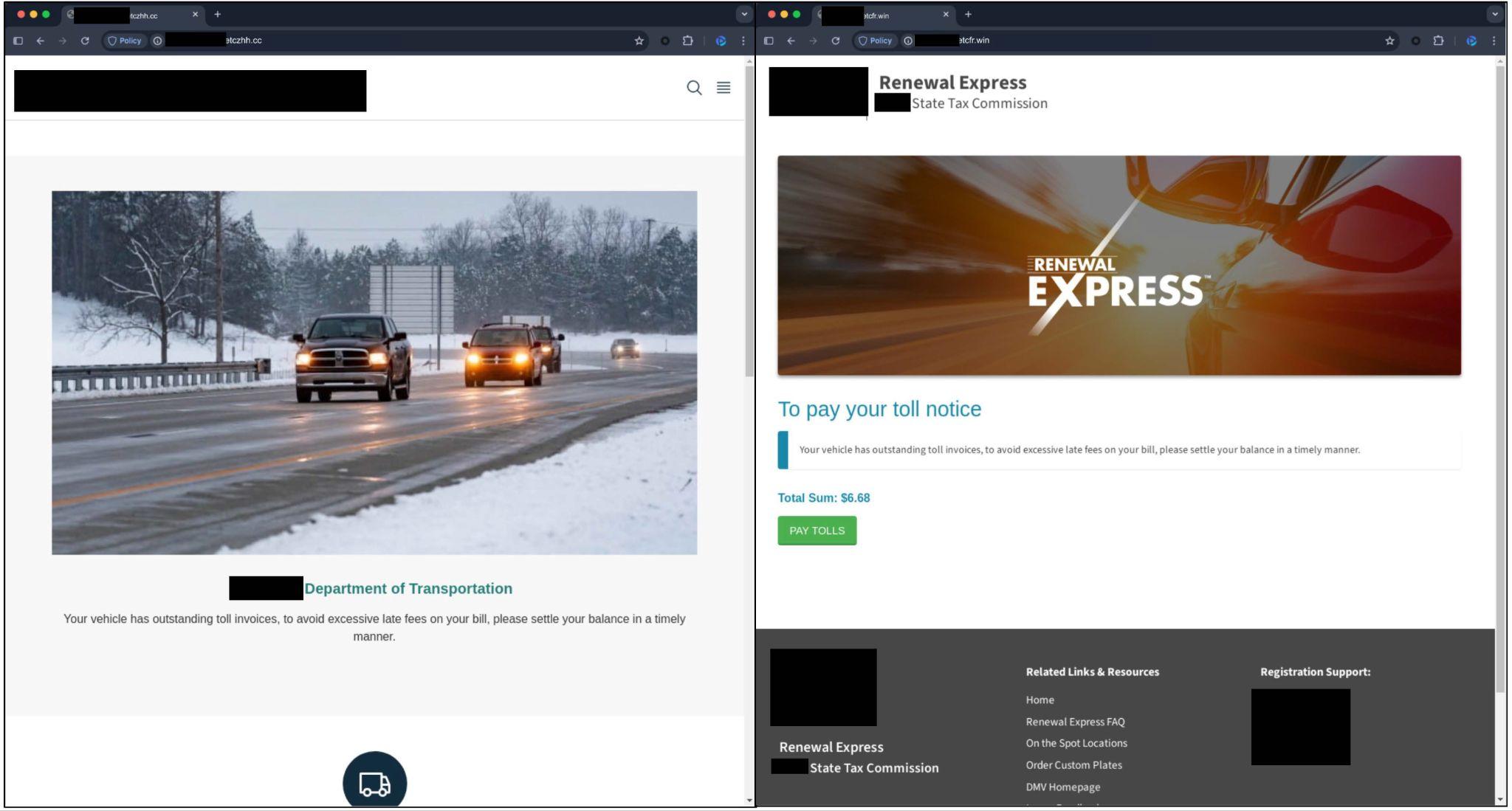

Phishing Impersonating Government Agencies

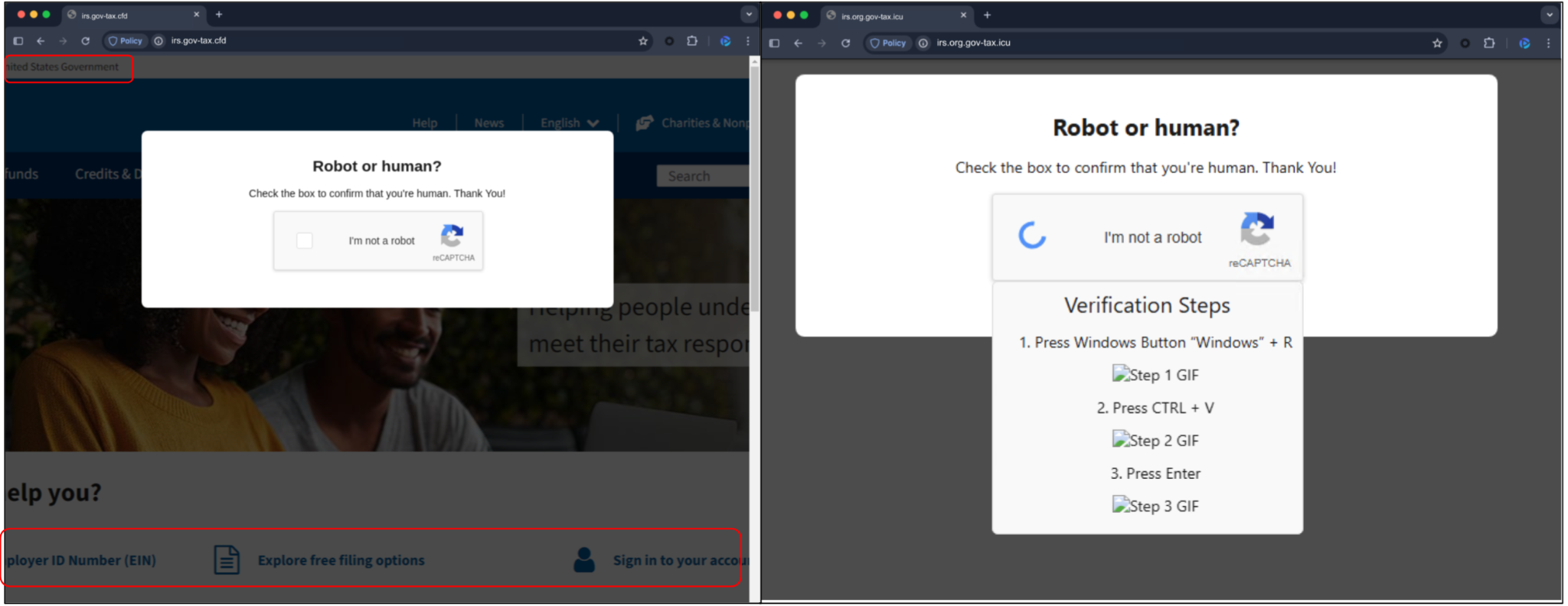

We have observed phishing pages impersonating government services such as the IRS and U.S. state vehicle departments and other transportation-related agencies.

These landing pages often mention unpaid toll and other service charges. They are potentially aimed at extracting login credentials, personal details and payment information.

Figure 9 shows examples of landing pages of domains impersonating state-specific electronic toll services. They use the state names and their services in the subdomain names and make use of state logos and emblems within the phishing pages.

Figure 10 shows examples of landing pages impersonating U.S. government agencies such as the IRS (128 FQDNs). The page contains a fake CAPTCHA page that is designed to manipulate users into executing malicious scripts on their machine.

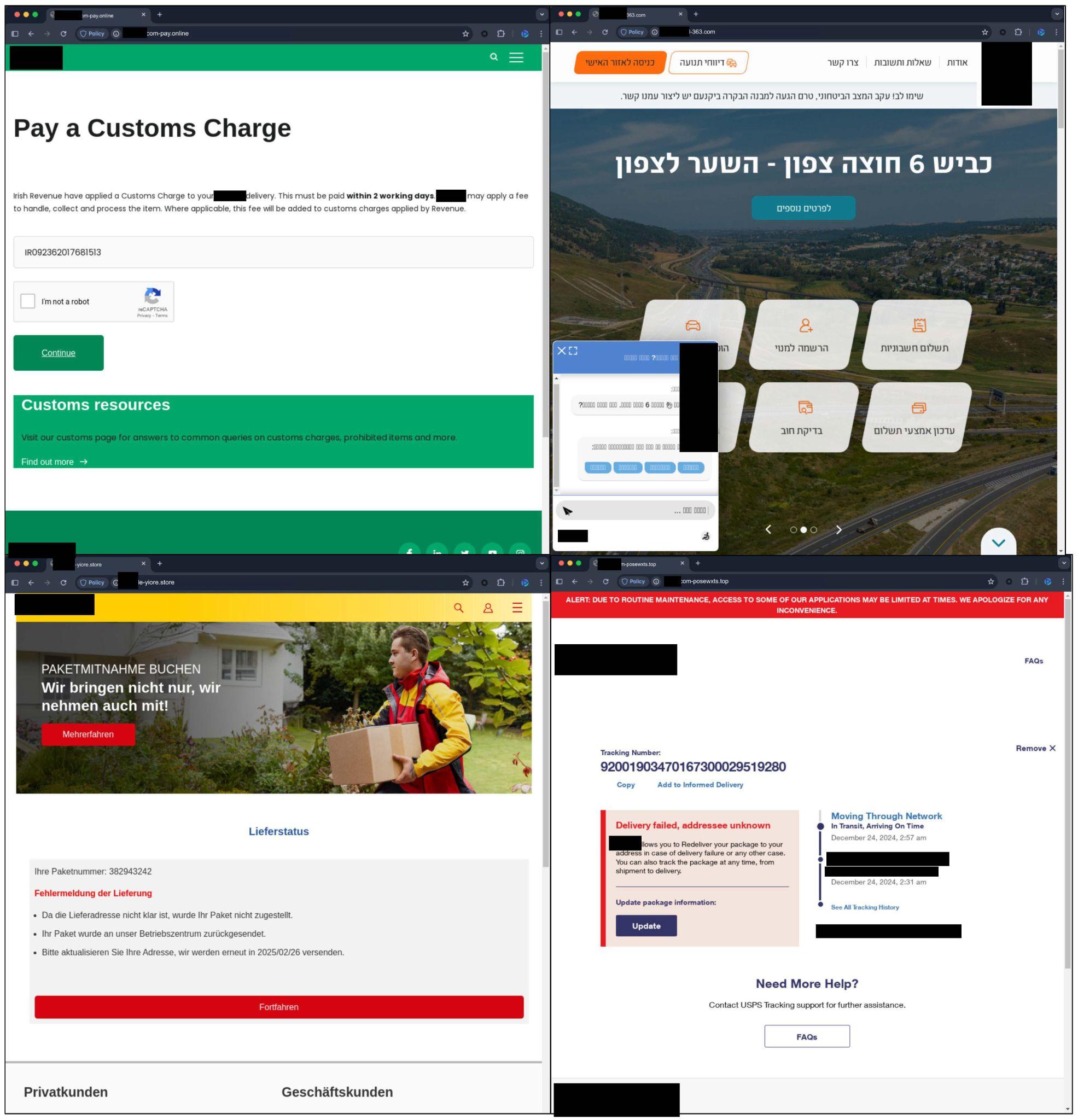

Misdelivery and Fake Customs Charges

Figure 11 shows several examples of landing pages containing fake notices of delivery failure, toll violation, international customs charges associated with popular mail and package delivery services, and toll services. These are potentially aimed at extracting personal information such as home addresses, contact details and payment information from victims.

Conclusion

We have uncovered that the smishing campaign impersonating U.S. toll services is not isolated. It is instead a large-scale campaign with global reach impersonating many services across different sectors. The threat is highly decentralized. Attackers are registering and churning through thousands of domains daily.

To track this rapidly evolving activity, we developed a multi-faceted intelligence framework that synthesizes data from WHOIS records, pDNS, evolving domain patterns, visual clustering of landing pages and graph-based infrastructure analysis.

We advise people to exercise vigilance and caution. People should treat any unsolicited messages from unknown senders with suspicion. We recommend that people verify any request that demands urgent action using the official service provider's website or application. This should be done without clicking any links or calling any phone numbers included in the suspicious message.

Palo Alto Networks Protection and Mitigation

Palo Alto Networks customers are better protected from the threats discussed above through the following products:

Advanced URL Filtering and Advanced DNS Security identify known domains and URLs associated with this activity as malicious.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America: Toll Free: +1 (866) 486-4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- UK: +44.20.3743.3660

- Europe and Middle East: +31.20.299.3130

- Asia: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

- Australia: +61.2.4062.7950

- India: 00080005045107

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Indicators of Compromise

- icloud.com-remove-device[.]top

- flde-lity.com-lg[.]icu

- michigan.gov-etczhh[.]cc

- utah.gov-etcfr[.]win

- irs.gov-tax[.]cfd

- irs.org.gov-tax[.]icu

- anpost.com-pay[.]online

- kveesh6.il-363[.]com

- dhl.de-yiore[.]store

- usps.com-posewxts[.]top

- e-zpass.com-etcha[.]win

- usps.com-isjjz[.]top

- flde-lity.com-jw[.]icu

- e-zpass.com-tollbiler[.]icu

- e-zpassny.com-pvbfd[.]win

- e-zpass.com-statementzz[.]world

- e-zpass.com-emea[.]top

- pikepass.com-chargedae[.]world

- e-zpass.com-etcoz[.]win

- e-zpassny.com-kien[.]top

- e-zpassny.com-xxai[.]vip

- sunpass.com-hbg[.]vip

- usps.com-hzasr[.]bid

- e-zpassny.gov-tosz[.]live

- michigan.gov-imky[.]win

- e-zpass.org-yga[.]xin

- e-zpass.org-qac[.]xin

- ezpass.org-pvwh[.]xin

- ezpassnj.gov-mhmt[.]xin

- e-zpassny.gov-hzwy[.]live

- irs.gov-addpayment[.]info

- irs.gov-mo[.]net

- israeipost.co-ykk[.]vip

- canpost.id-89b98[.]com

- anpost.id-39732[.]info

Additional Resources

- Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) | Smishing Scam Regarding Debt for Road Toll Services – FBI Public Service Announcement, Alert Number: I-041224-PSA

- Over 10k Domains Registered For Smishing Impersonating Toll And Package Delivery Services – Unit 42 Timely Threat Intelligence, GitHub

- Smishing Activity Update – Unit 42 Timely Threat Intelligence, GitHub

- Smishing Triad (Threat Actor) – Malpedia

- Unraveling the U.S. toll road smishing scams – Blog, Cisco Talos

- Smishing Triad: Chinese eCrime Group Targets 121+ Countries, Intros New Banking Phishing Kit – Silent Push

- DMV scam texts target people with bogus ticket warnings: What you should do – FOX 9 KMSP

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42