Executive Summary

While the majority of the IT industry is in the midst of adopting container-based infrastructure (cloud-native solution), it is imperative to understand the technology’s limitations. Traditional containers such as Docker, Linux Containers (LXC), and Rocket (rkt) are not truly sandboxed as they share the host OS kernel. They are resource-efficient, but the attack surface and the potential impact of a breach are still large, especially in a multi-tenant cloud environment that co-locate containers belonging to different customers. The root of the problem is the weak separation between containers when the host OS creates a virtualized userland for each container. There has been research and development focusing on designing truly sandboxed containers. Most of the solutions re-architect the boundary between the containers to fortify the isolation. This blog covers four unique projects from IBM, Google, Amazon, and OpenStack, respectively, that use different techniques to achieve the same goal, creating stronger isolation for containers. IBM Nabla builds containers on top of Unikernels, Google gVisor creates a specialized guest kernel for running containers, Amazon Firecracker is an extremely lightweight hypervisor for sandboxing applications, and OpenStack places containers in a specialized VM that is optimized for container orchestration platforms. The following overview of this state of the art research should help readers prepare for the upcoming transformation.

Overview of Current Container Technology

Containers are the modern way of packaging, sharing, and deploying an application. As opposed to a monolithic application in which all functionalities are packaged into a single software, containerized applications or microservices are designed to be single-purpose specializing in only one job. A container includes every dependency (e.g., packages, libraries, and binaries) that an application needs to perform its task. As a result, containerized applications are platform-agnostic and can run directly on any operating system regardless of its version or installed packages. This convenience saves developers tremendous effort of tailoring different versions of software for different platforms or customers. Although not entirely accurate, conceptually, many people like to think of containers as "lightweight virtual machines." When a container is deployed on a host, each container’s resources such as its file system, process, and network stack are placed in a virtually isolated environment which no other containers can access. This architecture allows hundreds or thousands of containers to run concurrently on the same cluster and each application (or microservice) can be easily scaled up by replicating more container instances.

Under the hood, the container evolvement is built on top of the two key building blocks, Linux namespace and Linux Control group (cgroup). Namespace creates a virtually isolated user space and gives an application its dedicated system resources such as file system, network stack, process id, and user id. In this isolated user space, the application controls the root directory of the file system starting with PID = 1 and may run as the root user. This abstracted userspace allows each application to run independently without interfering with other applications on the same host. There are currently six namespaces available: mount, inter-process communication (ipc), UNIX time-sharing system (uts), process id (pid), network, and user. Two additional namespaces, time and syslog, are proposed but the Linux community are still defining the specifications. Cgroup enforces hardware resources limitation, prioritization, accounting, and controlling of an application. Example hardware resources that cgroup can control are CPU, memory, device, and network. When putting namespace and cgroup together, we can securely run multiple applications on a single host with each application residing in its isolated environment. This is the fundamental property of a container.

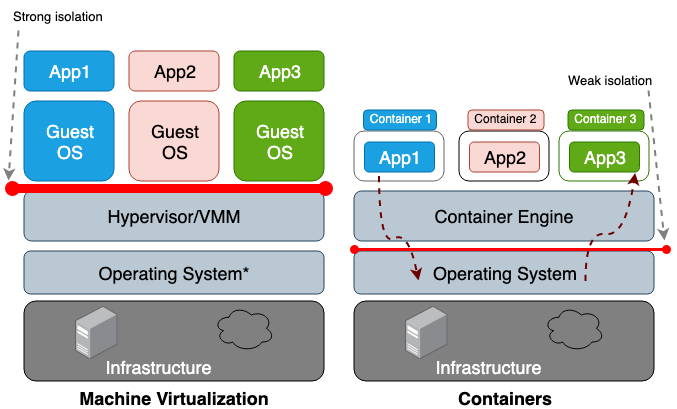

The main difference between a virtual machine (VM) and a container is that the VM is a hardware-level virtualization and a container is a OS-level virtualization. VM hypervisor emulates a hardware environment for each VM, where the container runtime emulates an operating system for each container. VMs share the host’s physical hardware and containers share both the hardware and the host’s OS kernel. Because containers share more resources from the host, their usages of storage, memory, and CPU cycles are all much more efficient than a VM. However, the downside of more sharing is the weaker trust boundary between the containers and the host. Figure 1 illustrates the architectural difference between a container and a VM.

Figure 1. In machine virtualization, hypervisor or virtual machine monitor (VMM) provides the isolation between each guest OS. In containers, the host operating system provides the isolation between each container.

Figure 1. In machine virtualization, hypervisor or virtual machine monitor (VMM) provides the isolation between each guest OS. In containers, the host operating system provides the isolation between each container.

* Only Type II VMM needs to run on operating system. Type I VMM runs on the physical hardware.

In general, virtualized hardware isolation creates a much stronger security boundary than namespace isolation. The risk of an attacker escaping a container (process) is much higher than the chance of escaping a VM. The reason for higher container escaping risk lies on the weak isolation that namespace and cgroup create. Linux implements namespace and cgroup by associating new property fields to each process. These fields under the /proc file system tell the host OS if one process can see the other or how much the CPU/Memory budget that the process can use. When viewing the running processes and threads from the host OS (e.g., top or ps commands), a container process looks just like any other process on the host. In general, traditional containers such as LXC or Docker are not considered truly sandboxed as containers on the same host share the same kernel. It is thus not surprising to see container escape vulnerabilities. For example, CVE-2014-3519, CVE-2016-5195, CVE-2016-9962, CVE-2017-5123, and CVE-2019-5736 can all lead to container breakout. Most kernel exploits should work for escaping containers as kernel exploits typically lead to privilege escalation and allow the compromised process to gain control outside its intended namespaces. Besides the attack vectors from software vulnerabilities, misconfiguration such as deploying a container with excessive privileges (e.g., CAP_SYS_ADMIN capability, privileged permission) or critical mount points (e.g., /var/run/docker.sock) may all lead to container escape. With these potential catastrophic outcomes, one should understand the risk when deploying containers in a multi-tenant cluster or having containers with sensitive data co-locate with other untrusted containers.

These security concerns motivate researchers to build stronger trust boundaries for containers. The idea is to create a real “sandboxed” container that is isolated from the host OS as much as possible. Most of the solutions involve creating a hybrid architecture that leverages the strong trust boundary from the VM and focus on better efficiency from the container. At the time of writing, there is no single project that is mature enough to be standardized, but the future container development will undoubtedly adopt some of these intriguing concepts. In the rest of the blog, we will go over several promising projects and compare their characteristics.

We start by introducing the Unikernel, the earliest single-purpose machine that packages the application with a minimal set of OS libraries into a single image. The concept of unikernel is fundamental to many future projects that aim to create secure, low-footprint, and optimized machine images. We then look at IBM Nabla, a project aiming to run unikernel applications like containers, and Google gVisor, a project that runs containers on a user-space kernel. After these two unikernel-like projects, we then move to VM-based container solutions, Amazon Firecracker and OpenStack Kata. The last section concludes the blog with a comparison of all the mentioned projects.

Unikernel

The advance of virtualization technologies has enabled the movement towards cloud computing. Hypervisors such as Xen and KVM are the fundamental building blocks that power Amazon Web Service (AWS) and Google Computing Platform (GCP). Although modern hypervisors are capable of handling hundreds of VMs in a cluster, VMs built from the traditional general-purpose operating systems are usually not optimized for running in a virtualization environment. A general-purpose OS is designed to support as many types of applications as possible, so its kernel includes all kinds of drivers, protocol libraries, and schedulers. However, most individual VMs deployed in the cloud today are dedicated to a single application such as DNS, proxy, or database. As each application only relies on a small subset of the kernel functions, the rest of the unused kernel functions waste the system resource and increase the attack surface. The larger the codebase is, the more vulnerabilities and bugs need to be managed. These problems motivate computer scientists to design single-purpose OSes with the minimal kernel functionalities to support just a single application.

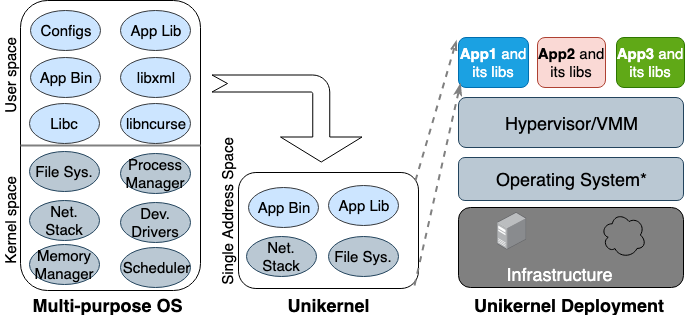

Operating system researchers first proposed the idea of "Unikernel" in the 1990s. Unikernel is a specialized and single-address-space machine image that can run directly on hypervisors. It packages the application and the application-dependent kernel functions into an image. Nemesis and Exokernel are the two earliest academic unikernel projects. Figure 2 illustrates how a unikernel machine image is created and deployed.

Figure 2. Multi-purpose OSes are built to support all types of applications, so many libraries and drivers are preloaded. Unikernels are specialized single-purpose OSes that are built to support a single application.

Figure 2. Multi-purpose OSes are built to support all types of applications, so many libraries and drivers are preloaded. Unikernels are specialized single-purpose OSes that are built to support a single application.

Unikernels break the kernel into multiple libraries and place only the application-dependent libraries into a single machine image. Like VMs, unikernels are deployed and run on virtual machine monitors. Due to their small footprints, unikernels can boot and scale up quickly. Unikernels’ most essential properties are improved security, small footprint, high optimization, and fast boot. Because unikernel images contain only the application dependent libraries, and a shell is unavailable unless specifically included, it has minimal attack surface that attackers can leverage. Not only is getting a foothold in unikernels difficult for attackers, but the impact of a compromise is also limited to a single unikernel instance. Because the size of unikernel images is just a few megabytes, unikernels can boot in tens of milliseconds and hundreds of instances can be run on a single host. Using the single-address-space memory allocation instead of the multilevel page table in most of the modern OSes, unikernel applications have lower memory access latency than the same application running in a VM. Because applications are compiled with the kernel when building the image, compilers can perform more static type checking to optimize the binaries.

Unikernel.org maintains a list of the unikernel projects. With all these salient properties, unikernels, however, have not gained much traction. When Docker acquired a unikernel startup, Unikernel Systems, in 2016 people thought that Docker would package containers into unikernels. After 3 years, there is still no sign of any integration. One main reason for this slow adoption is that there is still no mature tool to build unikernel applications and most of the unikernel applications can only run on specific hypervisors. Furthermore, porting an application to unikernel may require recoding with different languages and manually including the dependent kernel libraries. Monitoring or debugging in unikernels is either impossible or causes a significant performance impact. All these limitations hold back developers from migrating to unikernels. One should note that unikernels and containers share many similar properties. Both unikernels and containers are single-purpose images that are immutable, meaning that components in images cannot be updated or patched, and a new image is always created for an updated application. Unikernels today are like the pre-Docker era when no container runtime was available and developers need to use the basic building blocks to sandbox an application: chroot, unshare, and cgroup.

IBM Nabla

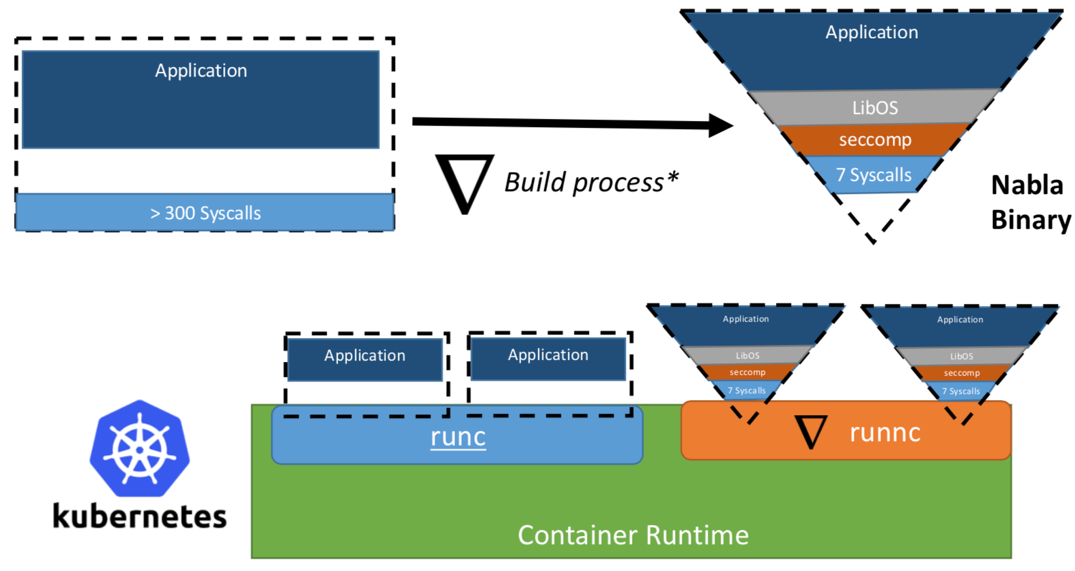

Researchers from IBM have proposed the idea of "Unikernel as process": that is a unikernel application run as a process on a specialized virtual machine monitor. IBM’s project "Nabla containers" further hardens the unikernel trust boundary by replacing the general-purpose monitor (e.g., QEMU) with their unikernel-specific monitor Nabla Tender. The rationale is that the hypercalls between the unikernels and the general-purpose Virtual Machine Monitor (VMM) still pose a large attack surface, so using a unikernel-specific monitor with fewer allowed system calls can significantly improve the security. Nabla Tender intercepts the hypercalls that unikernels send to the VMM and translates them to system calls. The Linux seccomp policy blocks all other system calls that Tender does not need. A unikernel together with Nabla Tender then runs as a user space process on the host. Figure 3 shows how Nabla creates a thin interface between the unikernel applications and the host.

Figure 3. To interface Nabla with the existing container runtime platforms, Nabla implements the OCI compliant runtime runnc that can be plugged into platforms like Docker and Kubernetes. Image source: Unikernels as Process

Figure 3. To interface Nabla with the existing container runtime platforms, Nabla implements the OCI compliant runtime runnc that can be plugged into platforms like Docker and Kubernetes. Image source: Unikernels as Process

The researchers claim that Nabla Tender uses less than seven syscalls to interface with the host. As syscalls serve as the bridge between the user space processes and the OS kernel, the fewer the available syscalls are, the smaller the attack surface exposed to the kernel. One additional benefit of running unikernel as a process is that the unikernel applications can be debugged with most process-based tools such as gdb.

To leverage the container orchestration platforms, Nabla also provides its Nabla runtime runnc that implements the Open Container Initiative (OCI) standard. The OCI standard specifies the API between runtime clients (e.g., Docker, Kubectl) and runtime (e.g., runc). Nabla also provides an image builder to create a unikernel image that runnc can execute. Due to the difference in file system between unikernels and traditional containers, Nabla images do not follow the OCI image specification and thus Docker images are not compatible with runnc. At the time of writing, the project is still in its early experimental stage. There are other limitations such as the lack of support for mounting/accessing host file systems, adding multiple network interfaces (needed for Kubernetes), or using images from other unikernel images (e.g., MirageOS and include OS).

Google gVisor

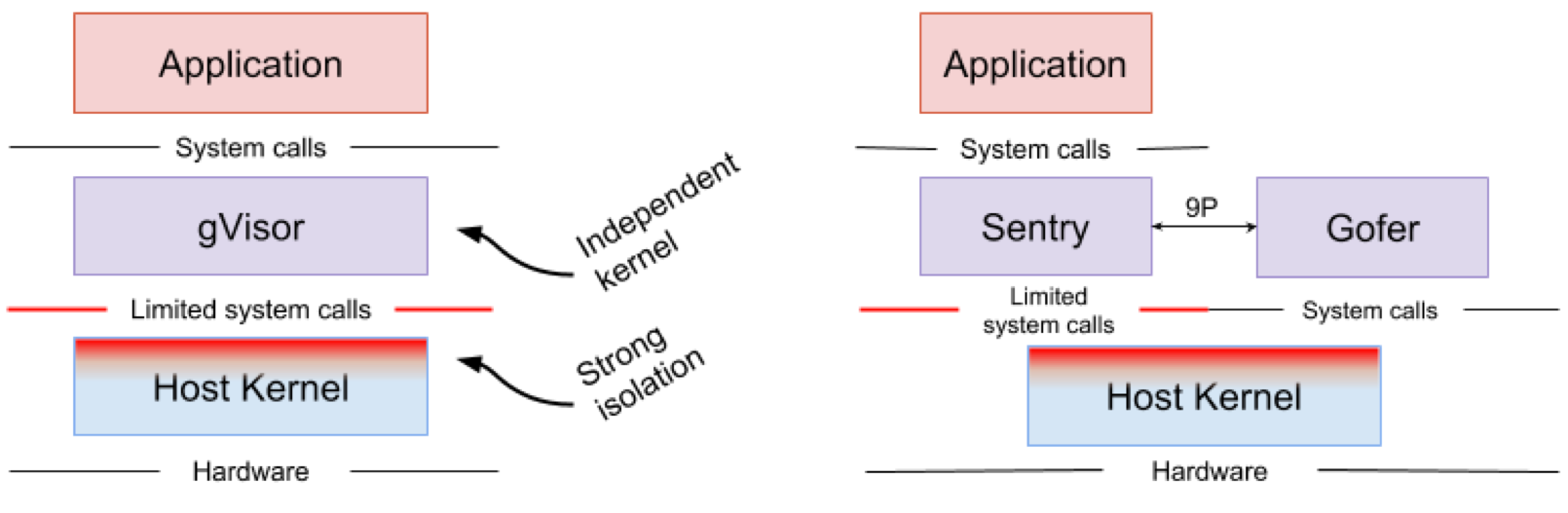

Google gVisor is the sandbox technology that powers Google Computing Platform’s (GPC) App Engine, Cloud Functions, and CloudML. Google realized the risk of running untrusted applications in the public cloud infrastructure and the inefficiency of sandboxing applications using VMs, and developed a user space kernel to sandbox the untrusted applications. gVisor sandboxes applications by intercepting all the system calls from applications to host kernel and handling them with gVisor's kernel implementation Sentry in user space. It essentially functions as a combination of guest kernel and VMM. Figure 4 shows gVisor's architecture.

Figure 4. gVisor kernel implementation Sentry and gVisor file system implementation Gofer use a small subset of syscalls to interface with the host. Image source: gVisor Architecture Guide, gVisor Overview and Platform

Figure 4. gVisor kernel implementation Sentry and gVisor file system implementation Gofer use a small subset of syscalls to interface with the host. Image source: gVisor Architecture Guide, gVisor Overview and Platform

gVisor creates a strong security boundary between an application and its host. This boundary restricts the syscalls that applications in user space can use. Without relying on the virtualized hardware, gVisor runs as a host process that interfaces between the sandboxed application and the host. Sentry implements most of the Linux system calls and essential kernel functions such as signal delivery, memory management, network stack, and threading model. Sentry has implemented more than 70% of the 319 Linux syscalls to support the sandboxed applications. For Sentry to communicate with the host kernel, it only uses less than 20 Linux syscalls. It is worth noting that gVisor and Nabla share a very similar strategy: defending the host OS. Both of them use less than 10% of the Linux syscalls to interface with the host kernel. While gVisor creates a multi-purpose kernel and Nabla relies on the unikernels, they both run a specialized guest kernel in user space to support the sandboxed applications.

One may wonder why gVisor needs to re-implement another Linux kernel while the open-source Linux kernel is readily available. gVisor's kernel written in Golang is more secure than the Linux kernel written in C due to the strong type safety and memory management features in Golang. Another important selling point of gVisor is its tight integration with Docker, Kubernetes, and the OCI standard. Most of the Docker images can be simply pulled and run with gVisor by changing the runtime to gVisor runsc. In Kubernetes, instead of sandboxing each container, an entire pod can be run in a gVisor sandbox.

As gVisor is still in its infancy, there are still some limitations. There is always overhead when gVisor intercepts and handles a syscall made by the sandboxed application, so it is not suitable for syscall heavy applications. (Note that there is no such overhead in Nabla as unikernel applications don’t make syscalls. Nabla uses seven syscalls only to handle the hyercalls.) gVisor has no direct hardware access (passthrough), so applications that require hardware access such as GPU cannot run in gVisor. Finally, as gVisor has not implemented all the Linux syscalls, applications that use unimplemented syscalls can't run in gVisor.

Amazon Firecracker

Amazon Firecracker is the technology that powers AWS Lambda and AWS Fargate today. It is a VMM that creates lightweight virtual machines (MicroVMs) specifically for multi-tenant containers and serverless operational models. Before Firecracker was available, Lambda functions and Fargate containers were running inside dedicated EC2 VMs for each customer to ensure the strong isolation. Although VMs create strong isolation for containers in public cloud, using general-purpose VMMs and VMs for sandboxing applications is not very resource-efficient. Firecracker solves both the security and performance issues by creating a VMM specifically for cloud-native applications. Firecracker VMM provides each guest VM with the minimal OS functionalities and emulated devices to enhance both the security and performance. Users can easily build VM images that run on Firecracker with a Linux kernel binary and ext4 file system image. Amazon started developing Firecracker in 2017 and made it open source in 2018.

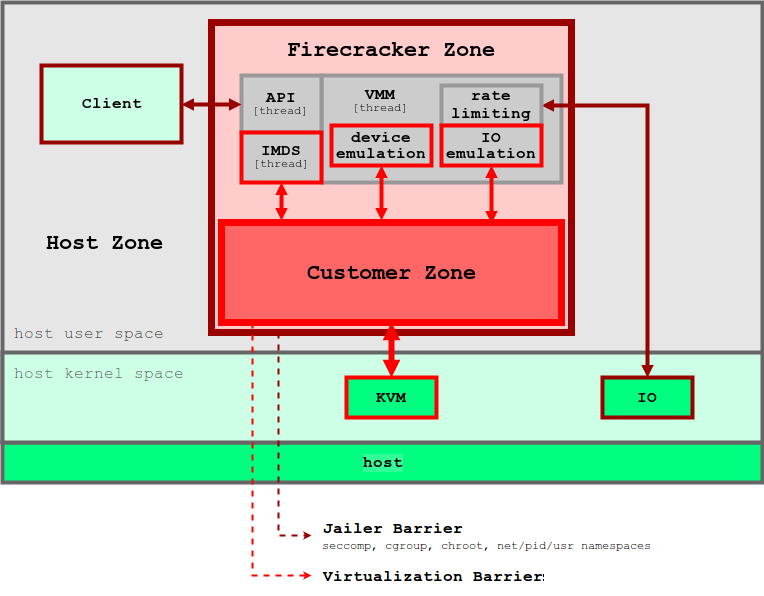

Similar to the unikernel concept, only a small subset of the devices and functionalities are provisioned to support the container operations. Compared to traditional VMs, microVMs have a much smaller attack surface, memory footprint, and boot time. Evaluation shows that a Firecracker microVM consumes ~5 MB memory and boots up in ~125 ms when running on a 2 CPU and 256G RAM host. Figure 5 shows the Firecracker architecture and its security boundary.

Figure 5. Firecracker VMM enforces layers of security boundary to isolate each user’s applications. Image source: Firecracker Design

Figure 5. Firecracker VMM enforces layers of security boundary to isolate each user’s applications. Image source: Firecracker Design

Firecracker VMM relies on KVM and each Firecracker instance runs as a user space process. Each Firecracker process is locked down by the seccomp, cgroup, and namespace policies so that the system calls, hardware resource, file system, and network activities are strictly limited. There are multiple threads inside each Firecracker process. API thread provides the control plane between the clients on the host and the microVM. VMM thread provides a minimal set of virtIO devices (net and block). Firecracker provisioned only four emulated devices for each microVM: virtio-block, virtio-net, serial console, and a 1-button keyboard controller used only to stop the microVM. For security purpose, VMs do not have a mechanism to share files with the host. The data on the host such as container images are exposed to microVMs through File Block Devices. The network interfaces for VMs are backed by the tap devices over a network bridge. All the outbound packets are copied to the tap device and rate-limited by cgroup policy. The layers of security boundary minimize the chance of having one user’s applications disrupt the other’s.

At the time of writing, Firecracker has not yet fully integrated with Docker and Kubernetes. Firecracker does not support hardware passthrough, so applications that need GPU or any device accelerator access are not compatible. It has limited VM-to-host file sharing and networking models as well. However, as the project is backed by a large community, it should be soon interfaced with the OCI standard and supports more applications.

OpenStack Kata

Seeing the security concerns of the traditional containers, Intel launched their VM-based container technology Clear Containers in 2015. Clear containers rely on the Intel® VT hardware-based virtualization technology and a highly-customized QEMU-KVM hypervisor qemu-lite to realize a high performance VM-based container. At the end of 2017, Clear containers project joined with Hyper RunV, a hypervisor-based runtime for OCI, to initiate the Kata containers project. Inheriting all the properties of the Clear Containers, Kata Containers now support a wider variety of infrastructures and container specifications.

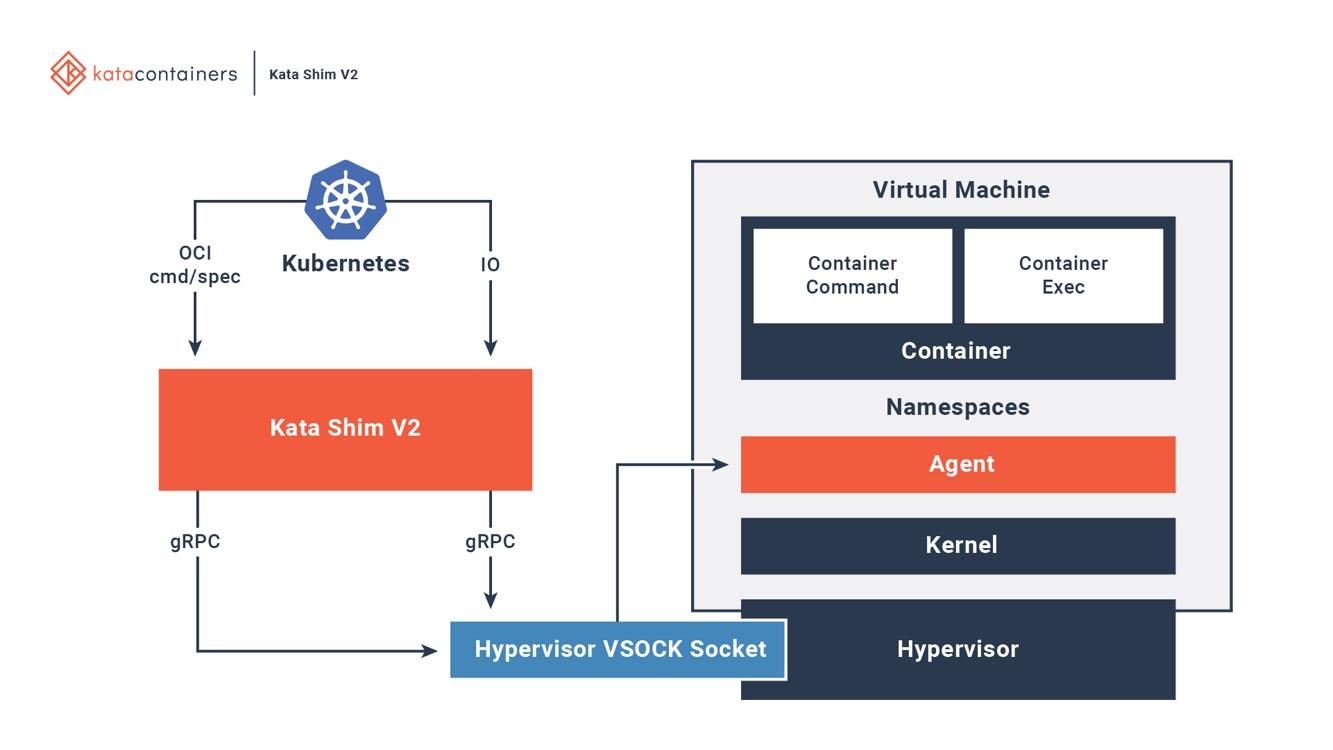

Kata container is fully integrated with OCI, Container Runtime Interface (CRI), and Container Networking Interface (CNI). It supports various types of networking models (e.g., passthrough, MacVTap, bridge, tc mirroring) and configurable guest kernels so that the applications requiring special networking models or kernel versions can all run on it. Figure 6 shows how containers inside Kata VMs interact with the existing orchestration platforms.

Figure 6. Kata containers are fully integrated with Docker and Kubernetes. Image source: An overview of the Kata Containers project

Figure 6. Kata containers are fully integrated with Docker and Kubernetes. Image source: An overview of the Kata Containers project

Kata has a kata-runtime on the host to start and configure new containers. For each container in Kata VM, there is a corresponding Kata Shim on the host. Kata Shim receives API requests from the clients (e.g., docker or kubectl) and forwards the requests to the agent inside the Kata VM through VSock. Kata containers further make several optimizations to reduce the VM boot time. NEMU is a lightweight version of QEMU with ~80% of devices and packages removed. VM-Templating creates a clone of running Kata VM instance and shares it with other newly created Kata VMs. It significantly reduces the boot time and guest VM memory consumption but may be vulnerable to cross-VM side-channel attack like CVE-2015-2877. Hotplug capability allows a VM to boot with the minimal resources (e.g., CPU, memory, virtio block) and add additional resources later when requested.

Kata containers and Firecracker are both VM-based sandbox technology designed for cloud-native applications. They share the same goal but take very different approaches. Firecracker is a specialized VMM that creates a secure virtualization environment for guest OSes while Kata containers are lightweight VMs that are highly optimized for running containers. There has been efforts to run Kata containers on the Firecracker VMM. While the project is still experimental, it can potentially bring together the best features of the two projects.

Conclusion

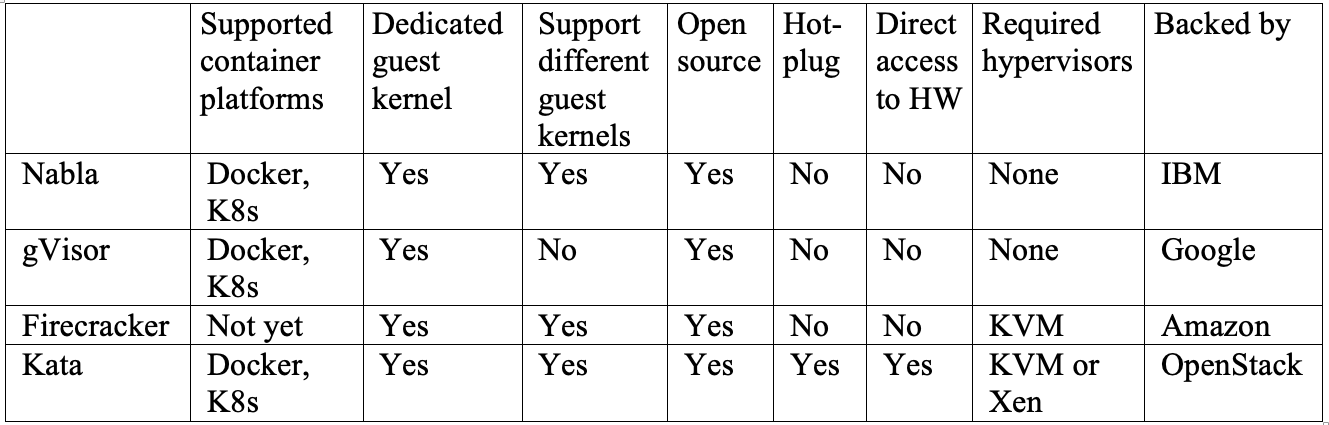

We have looked at several solutions that tackle the current container technology’s weak isolation issue. IBM Nabla is a unikernel-based solution that packages applications into a specialized VM. Google gVisor is a merge of a specialized hypervisor and guest OS kernel that provides a secure interface between the applications and their host. Amazon Firecracker is a specialized hypervisor that provisions each guest OS a minimal set of hardware and kernel resources. OpenStack Kata is a highly optimized VM with built-in container engine that can run on hypervisors. It is difficult to say which one works best as they all have different pros and cons. Table 1 shows a side-by-side comparison of some important features across all four projects. Nabla is your best choice if you have applications running in unikernels such as MirageOS or IncludeOS. gVisor is currently integrated best with Docker and Kubernetes, but due to its incomplete system call coverage, some applications still cannot run on it. Firecracker supports customized guest OS images, so it is a good choice if your applications need to run in a customized VM. Kata containers are fully compliant with the OCI standard and can run on both KVM and Xen hypervisor. It can simplify deploying microservices in an environment of hybrid platforms. While it may take some time for one or multiple solutions to eventually be adopted by the mainstream, it is positive to see that most cloud providers have taken action on mitigating the issue. For organizations who are building on-premises cloud-native platforms, it is not the end of the world. Common practices such as patching quickly, least privilege configuration, and network segmentation can all effectively reduce the attack surface.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42