This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

For three years, Unit 42 has tracked a set of cyber espionage attack campaigns across Asia, which used a mix of publicly available and custom malware. Unit 42 created the moniker “PKPLUG” for the threat actor group, or groups, behind these and other documented attacks referenced later in this report. We say group or groups as our current visibility doesn’t allow us to determine with high confidence if this is the work of one group, or more than one group which uses the same tools and has the same tasking. The name comes from the tactic of delivering PlugX malware inside ZIP archive files as part of a DLL side-loading package. The ZIP file format contains the ASCII magic-bytes “PK” in its header, hence PKPLUG.

While tracking these attackers, Unit 42 discovered additional, mostly custom malware families being used by PKPLUG beyond that of just PlugX. The additional payloads include HenBox, an Android app, and Farseer, a Windows backdoor. The attackers also use the 9002 Trojan, which is believed to be shared among a small subset of attack groups. Other publicly available malware seen in relation to PKPLUG activity includes Poison Ivy and Zupdax.

During our investigations and research into these attacks, we were able to relate previous attacks documented by others that date back as far back as six years ago. Unit 42 incorporates these findings, together with our own, under the moniker PKPLUG and continue to track accordingly.

It’s not entirely clear as to the ultimate objectives of PKPLUG, but installing backdoor Trojan implants on victim systems, including mobile devices, infers tracking victims and gathering information is a key goal.

We believe victims lay mainly in and around the Southeast Asia region, particularly Myanmar, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Indonesia; and likely also in various other areas in Asia, such as Tibet, Xinjiang, and Mongolia. Based on targeting, content in some of the malware and ties to infrastructure previously documented publicly as being linked to Chinese nation-state adversaries, Unit 42 believes with high confidence that PKPLUG has similar origins.

Targeting

Based on our visibility into PKPLUG’s campaigns and what we’ve learned from collaborating with industry partners, we believe victims lay mainly in and around the Southeast Asia region. Specifically, the target countries/provinces include (with higher confidence), Myanmar and Taiwan as well as (with lower confidence), Vietnam and Indonesia. Other areas in Asia targeted include Mongolia, Tibet and Xinjiang. This blog, and the associated Adversary Playbook, provides further details including: the methods used for malware delivery, the social engineering topics of decoy applications and documents and the Command & Control (C2) infrastructure themes.

Indonesia, Myanmar and Vietnam are ASEAN members, contributing towards intergovernmental cooperation in the region. Mongolia, specifically the independent country also known as Outer Mongolia, has a long-standing and complex relationship with the PRC. Tibet and Xinjiang are autonomous regions (AR) of China that tend to be classified by China’s ethnic minorities, granted the ability to govern themselves but ultimately answering to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Tibet and Xinjiang are the only ARs, from five, where the ethnic group maintains a majority over other populations.

Most, if not all, of the seven countries or regions, are involved in some way with Beijing's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) designed to connect 71 countries across Southeast Asia to Eastern Europe and Africa. The path through Xinjiang is especially important to the BRI’s success, but is more often heard of due to conflicts between the Chinese government and the ethnic Uyghur population. News of the BRI is peppered with stories of success and failure, of countries for and against the BRI and of countries pulling out of existing BRI projects.

Further tensions in the region are attributed to ownership claims over the South China Sea, including fishing quotas and the yet unproven oil and gas reserves. At least three of the target countries mentioned (Malaysia, Taiwan and Vietnam) have laid claim to parts of these waters, and some use the area for the vast majority of their trade. Foriegn militaries also patrol, attempting to keep the area open.

Taiwan, which isn’t an AR and doesn’t appear to be actively involved with the BRI, has its own long-standing history with the PRC -- a recent $2.2 billion arms sale with the U.S. may exacerbate matters.

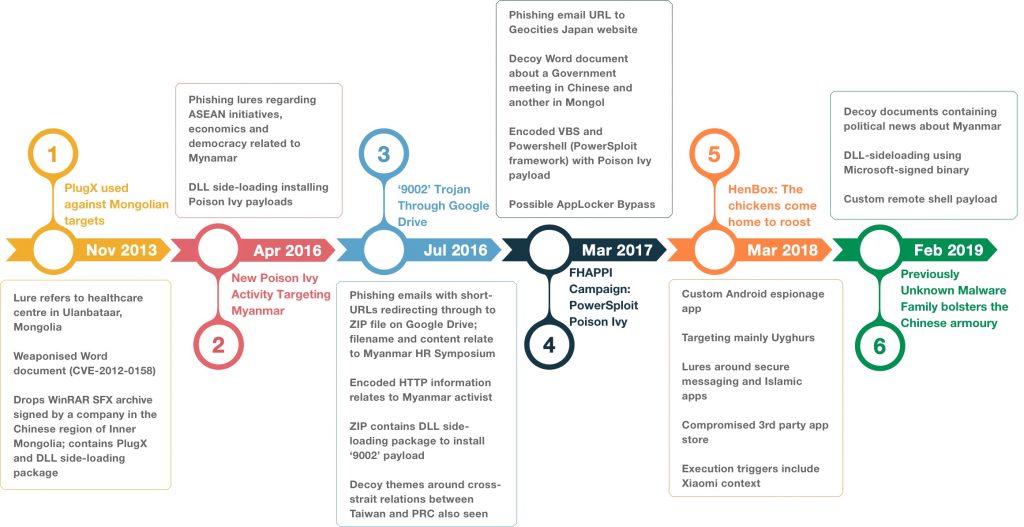

Timeline

Before continuing, it’s worth highlighting our research and others relating to the intrusion set that we refer to as PKPLUG. This section documents prior work surrounding cyber attacks relating to PKPLUG. The following figure illustrates the chronological order of the publications -- highlighting some key findings from each.

As you can see from the timeline, PKPLUG has been active for six years or more with a variety of targets and methods of delivery and compromise.

Figure 1. Timeline of publications and key findings relating to PKPLUG

Please note: the dates shown on the horizontal timeline bar in Figure 1 above relate to the publishing date, not the campaign dates, although some were fairly close together. As an example to illustrate the difference in dates, HenBox was discovered in 2018 but has samples ranging from 2015 through to this week. PlugX and Poison Ivy are still doing the rounds and their use by different groups is well known. Whether they relate to PKPLUG is another matter.

#1: In November 2013, Blue Coat Labs published a report describing a case of attacks against Mongolian targets using PlugX malware. Like so many other attacks using PlugX over the past decade or more, Blue Coat noted the DLL side-loading technique used to launch the malicious payload via legitimate, signed applications. Their report also documented the group’s use of an exploit against software vulnerabilities in Microsoft Office. In this case, using a weaponized Word document saved as a Single File Web Page format -- usually having an mht file extension -- in order to exploit CVE-2012-0158 to drop and execute a signed WinRAR SFX archive containing the side-loading package and PlugX payload. Considering all the malware related to PKPLUG that Unit 42 has analyzed, the use of such exploits appears to be less common than a spear-phishing technique making use of social engineering to lure victims into running their malware.

#2: A report published in April 2016 by Arbor Networks detailed recent cyber attacks using Poison Ivy malware against targets in Myanmar and other countries in Asia over the previous twelve months.

They noted phishing emails using ASEAN membership, economics and democracy-related topics to weaponize documents delivering the Poison Ivy payloads. While Arbor didn’t know the exact victims, they inferred suspect targets based on the content of emails and associated malware. DLL side-loading was also mentioned as the method to install the malware.

#3: Unit 42 published research that reported attacks using the 9002 Trojan delivered through Google Drive. The download originated with a spear-phishing email containing a shortened URL that redirected multiple times before downloading a ZIP file hosted on Google Drive. The redirection using HTTP also contains information about the victim who received the spear-phish and clicked the link. In this case, the information related to a well-known politician and human rights activist in Myanmar. The filename of the ZIP archive also related to initiatives in the country, as did the decoy document contents. The ZIP file contained a DLL side-loading package abusing a Real Player executable signed by RealNetworks, Inc. in order to load the 9002 payload.

#4: In March 2017, researchers published a report in Japanese (later translated into English) that described attacks seen by VKRL -- a Hong Kong-based cybersecurity company -- that were using spear-phishing emails with URLs using GeoCities Japan to deliver malware. The content of the website contained encoded VBScript that executed PowerShell commands to download a Microsoft Word document from the same GeoCities site, as well as another encoded PowerShell script closely resembling PowerSploit -- a PowerShell post-exploitation framework for pentesters that’s available on GitHub -- that was responsible for decoding and launching a Poison Ivy payload.

Another GeoCities account was found hosting similar packages, including one targeting Mongolia based on the contents of the decoy documents. The contents of the file, assuming a victim clicked on the URL in the spear-phishing email, resembles the structure used in a technique known as AppLocker Bypass whereby trusted Windows executables can be used to execute malicious payloads.

#5: In early 2018, Unit 42 discovered a new Android malware family that we named “HenBox” and is tracking over 400 related samples dating back as far as late 2015, and continuing to present day. HenBox often masquerades as legitimate Android apps and appears to primarily target the Uyghurs -- a minority Turkic ethnic group that is primarily Muslim and lives mainly in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in Northwest China and also targets devices made by Chinese manufacturer Xiaomi.

Smartphones are the dominant form of internet access in the region and hence make good targets for such malware. Once installed, HenBox steals information from a myriad of sources on the device including harvesting outgoing phone calls to numbers with an “+86” prefix -- the country code for the PRC -- and accessing the device microphone and cameras.

During investigations, data revealed an older version of HenBox had been downloaded from the uyghurapps[.]net website, which appears to be third-party Android app store serving the Uyghur community based on the domain name, language of the site and app content hosted. HenBox was masquerading as an another app -- DroidVPN -- which was also embedded within HenBox and installed post-infection.

#6: Based on further investigations and pivoting around HenBox infrastructure, Unit 42 discovered a previously-unknown Windows backdoor Trojan called Farseer. Farseer also uses the DLL side-loading technique to install payloads -- this time favoring a signed Microsoft executable from VisualStudio to appear benign. A VBScript component is used, via a registry persistence hook, to launch the Microsoft executable and the Farseer payload during the user login process. In earlier Farseer variants, we saw decoy documents being used, including one case of a PDF containing a news article relating to Myanmar. Mongolia also appears to be a target based on telemetry provided by an industry partner of ours.

Further information relating to these publications, together with respective Indicators of Compromise (IoC) and Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) used, are available in the PKPLUG Adversary Playbook.

Tying It All Together

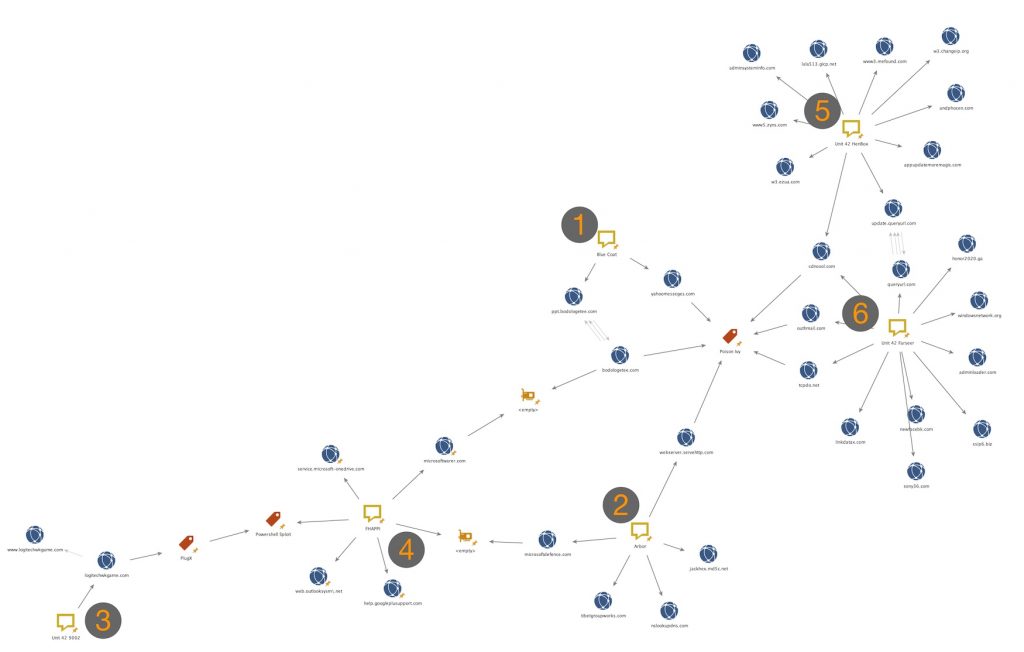

The following Maltego image shows the vast majority of known infrastructure and some of the known malware samples related to PKPLUG, and the chart continues to grow as we discover more about this adversary. The indexed shapes that overlay the figure provide a reference back to the published work chronology mentioned above.

Figure 2. PKPLUG Maltego diagram highlighting published research

Overlaps between the different campaigns documented, and the malware families used in them, exist both in infrastructure (domain names and IP addresses being reused, sometimes in multiple cases) and in terms of malicious traits (program runtime behaviors or static code characteristics are also where relationships can be found or strengthened).

Figure 3 below shows a very simplified view of the six core publications again, as per Figure 2 above, but with trimmed-down infrastructure to highlight some of the core overlaps.

Figure 3. Simplified Maltego diagram showing high-level ties

The C2 infrastructure blogged by Blue Coat Labs in their publication (#1) “PlugX used against Mongolian targets” included ppt.bodologetee[.]com has infrastructure ties microsoftwarer[.]com through a shared IPv4 with parent domain bodologetee[.]com. Domain microsoftwarer[.]com was found after threat hunting based on facts provided in publication (#4) “"FHAPPI” Campaign: FreeHosting APT PowerSploit Poison Ivy” in relation to the FHAPPI campaign.

The FHAPPI campaign (#4) was documented as using PowerShell and PowerSploit code in order to infect victims with Poison Ivy, but very similar code was also found around PlugX malware, some of which had C2 communication with logitechwkgame[.]com. Domain logitechwkgame[.]com was documented by Unit 42 in publication (#3) “Attack Delivers 9002 Trojan Through Google Drive” as the C2 for the 9002 Trojans analyzed. FHAPPI is also connected through another malware using C2 infrastructure that relates, through a shared IPv4 address, to microsoftdefence[.]com, which malware documented in Arbor Networks’ publication (#2) “Poison Ivy Activity Targeting Myanmar, Asian Countries” also used for C2 communication. Other Poison Ivy samples also related to the campaigns documented by Arbor Networks used domain webserver.servehttp[.]com for C2 communication. Said samples also shared overlaps in runtime characteristics with other Poison Ivy samples that have been analyzed and confirmed as having C2 communications with certain domains that relate to both Blue Coat Labs’ publication (#1) and Unit 42’s research into Farseer malware and their publication (#6) “Farseer: Previously Unknown Malware Family bolsters the Chinese armoury”. Domains include yahoomesseges[.]com and outhmail[.]com, tcpdo[.]net, queryurl[.]com and cdncool[.]com respectively. The same registrant of yahoomesseges[.]com - mongolianews@yahoo[.]com - also registered ppt.bodologetee[.]com mentioned slightly earlier.

Some HenBox malware has used domain cdncool[.]com as well for its C2 communications, as documented in Unit 42’s publication (#5) “The Chickens Come Home to Roost.” Domain cdncool[.]com is thus connected not only to HenBox and Farseer campaigns, but also, through Poison Ivy malware, to the campaigns documented by Blue Coat Labs and Arbor Networks. HenBox is also connected through a third-level domain update.queryurl[.]com to queryurl[.]com that has been used for C2 communications by some Farseer samples.

Other overlaps, mainly in infrastructure also exist (as seen in Figure 2 above) but are difficult to describe in a blog like this, hence using Maltego. Figure 3, as mentioned earlier, is a simplified diagram to highlight some core overlaps.

PKPLUG’s Adversary Playbook

Unit 42 has previously described and published Adversary Playbooks you can view using our Playbook Viewer. To recap briefly, Adversary Playbooks provide a Threat Intelligence package in STIX 2.0 that include all IoCs for known attacks by a given adversary. In addition, said packages also include structured information about attack campaigns and adversary behaviours -- their TTPs) -- described using Mitre’s ATT&CK framework.

The Adversary Playbook for PKPLUG can be viewed here, and the STIX 2.0 content behind that can be downloaded from here. The Playbook contains several Plays (aka campaigns; instances of the Attack Lifecycle) that map, for the most part, to published research previously mentioned in this blog. There exists Plays including specific details from publications by Blue Coat Labs, Arbor Networks, our publication on the 9002 Trojan, and the FHAPPI campaign. HenBox has two Plays -- one for the known attack compromising a third-party app store to deliver the malware and another containing all other HenBox data. A similar single campaign exists for Farseer containing all related data.

Conclusion

Establishing a clear picture and understanding about a threat group, or groups, is virtually impossible without total visibility into every one of their attack campaigns. Based on this, applying a handle or moniker to a set of related data -- such as network infrastructure, malware behavior, actor TTPs relating to delivery, exfiltration, etc. -- helps us to better understand what it is we’re investigating. Sharing this information -- with a handle, in this case PKPLUG -- especially in a structured, codified manner a la Adversary Playbooks, should allow others to contribute their vantage points and enrich said data until the understanding of a threat group becomes lucid.

Based on what we know and what we’ve gleaned from others’ publications, and through industry sharing, PKPLUG is a threat group, or groups, operating for at least the last six years using several malware families -- some more well-known: Poison Ivy, PlugX, and Zupdax; some are less well-known: 9002, HenBox, and Farseer. Unit 42 has been tracking the adversary for three years and based on public reporting believes with high confidence that it has origins to Chinese nation-state adversaries. PKPLUG targets various countries or provinces in and around the Southeast Asia region for multiple possible reasons as mentioned above, including some countries that are members of the ASEAN organisation, some regions that are autonomous to China, some countries and regions somewhat involved with China’s Belt and Road Initiative, and finally, some countries that are embroiled in ownership claims over the South China Sea.

The Playbook Viewer helps to highlight some of the more common TTPs used by PKPLUG but, based on our visibility, spear-phishing emails to deliver payloads to their victims is very popular. Some email attachments contained exploits taking advantage of vulnerable Microsoft Office applications, however this technique was less commonly used compared with social engineering to lure the victim into opening attachments. DLL side-loading seems almost ubiquitous as a method to install or run their payloads, though perhaps more recently, PowerShell and PowerSploit is also being considered. Other TTPs are described in the STIX 2.0 package and presented in the Viewer.

The use of Android malware shows intent to get at targets where perhaps traditional computers, operating systems and ways of communicating are different from previous targets.

Palo Alto Networks detects customers are protected by these threats through the following:

- Customers using AutoFocus can view this activity by using the following tags:

PKPlug - All malware identified are detected as malicious by WildFire and Traps

Palo Alto Networks has shared our findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, in this report with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. For more information on the Cyber Threat Alliance, visit www.cyberthreatalliance.org.

Indicators of Compromise

Indicators of compromise relating to PKPLUG can be found in the Adversary Playbook through the Playbook Viewer itself, or indirectly from the STIX 2.0 JSON file powering it.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.