Executive Summary

When malware authors go to great lengths to avoid behaving maliciously if they detect they’re running in a sandbox, sometimes the best answer for security defenders is to write their own sandbox that can’t easily be detected. There are a lot of sandboxing approaches out there with pros and cons to each. We’ll talk about why we chose to go the bespoke route, and we’ll discuss many of the evasion types we had to cover in that effort as well as strategies that can be used to counter them.

There are many variations on how malware authors specifically detect sandboxes, but the general theme is that they will check the characteristics of the environment to see whether it looks like a targeted host rather than an automated system.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive improved detection for the evasions discussed in this blog through Advanced WildFire.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Sandbox, WildFire, evasive malware |

How We Became Evasion Connoisseurs

You could say that our day to day in the world of malware analysis has made the WildFire malware team sandbox evasion connoisseurs. Our team’s Slack channel has had its share of “look at this one!” over the years, sharing the joy of finding new evasion techniques. Getting to the bottom of these has been a big part of our team mission to help improve detection.

There’s a vast number of techniques malware authors use to check if they are running on a “real” targeted host, such as counting the number of cookies in browser caches, or checking whether video memory appears too small. Given that sandbox evasions are legion and there are far too many to cover in a single article, we will first examine some of the major categories we typically encounter and then cover what we can do about them.

Checks for Instrumentation or “Hooks”

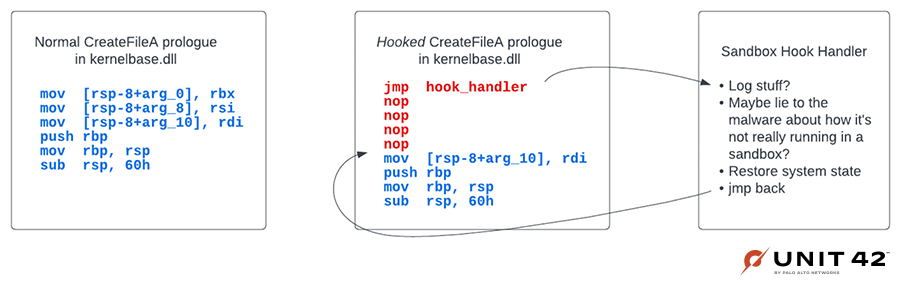

The first broad category of evasions involves the detection of any sandbox instrumentation. This is definitely one of the most popular techniques. The most common example is checking for API hooks, as this is a common method for sandboxes and antivirus vendors alike to instrument and log all of the API calls made by an executable under analysis. This can be as simple as checking the function prologues of common functions to see if they are hooked.

In Figure 1, we see what the disassembly looks like for the prologue of CreateFileA in Windows 10 as well as what it might look like if it’s been instrumented in a sandbox.

As you can see, this is pretty easy for attackers to detect, which is why it’s one of the most prevalent evasions we’ve seen out there.

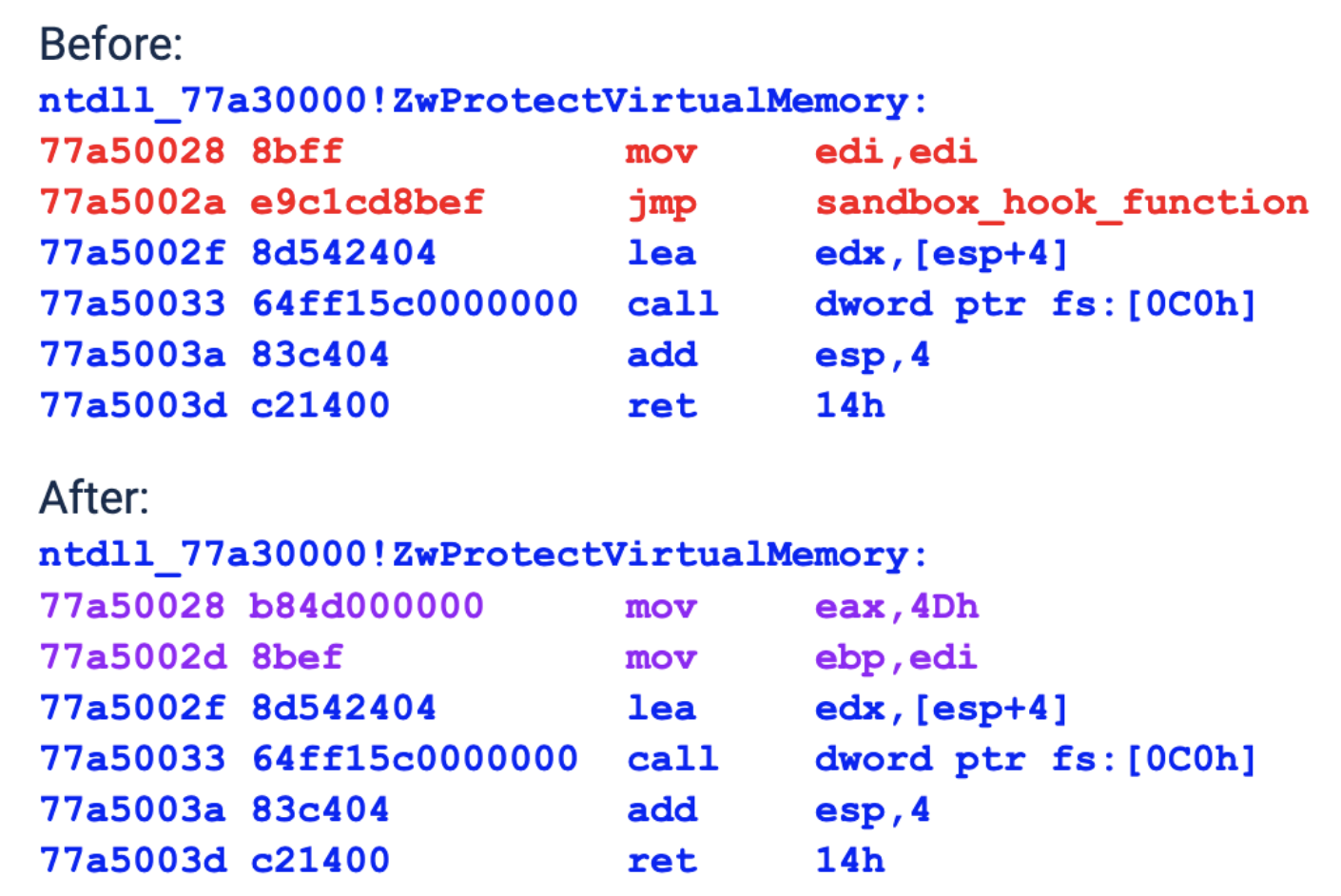

A fun variation on this technique is when malware detects and unhooks existing hooks in order to stealthily execute without having its activity logged. This happens when malware authors want to slide past endpoint protections without being detected on a targeted host.

Figure 2 shows an example of how GuLoader unpatches the bytes of the ZwProtectVirtualMemory function prologue to restore the original functionality.

Mitigating Instrumentation Evasions

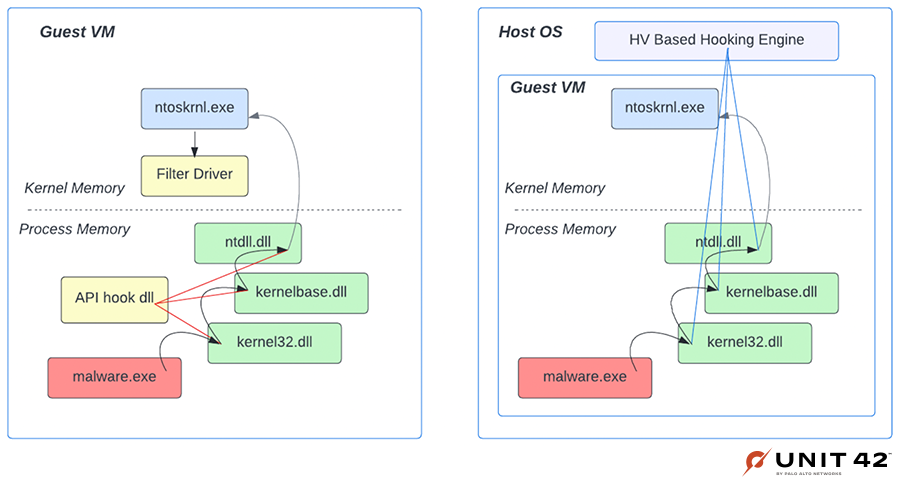

The gold standard for preventing malware authors from detecting instrumentation is simply not to have anything out of the ordinary that’s visible to the program you’re analyzing. A growing number of sandboxes are making this idea the focus of their detection strategy. It’s easier to be evasion resistant when you don’t change a single byte anywhere in the OS.

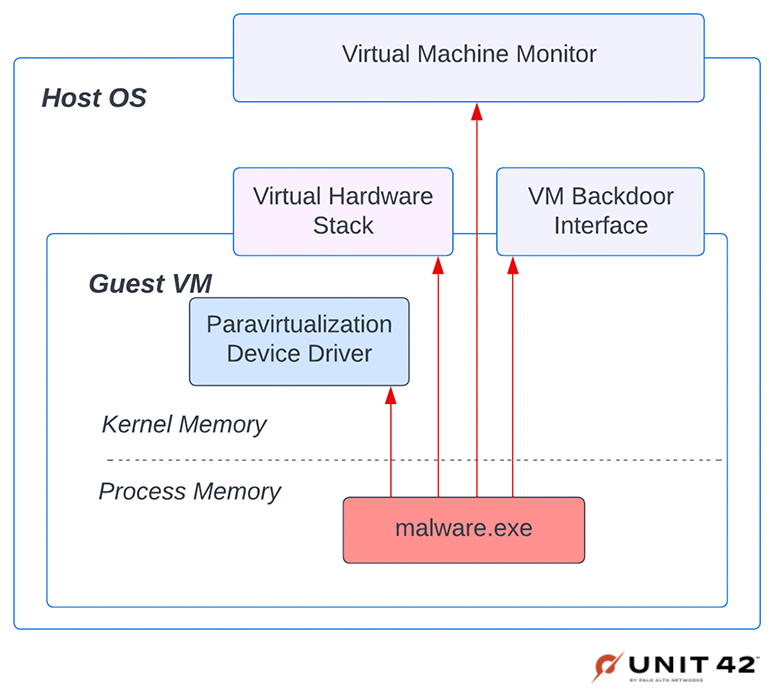

Instead of instrumenting APIs by changing code, it’s a better strategy to use virtualization to invisibly instrument programs under analysis. There are a lot of advantages to instrumenting malware from outside of the guest VM, as shown in Figure 3.

Detecting Virtual Environments

Another common evasion category involves detecting that a file is executing in a virtual machine (VM). This can involve fingerprinting resources like low CPU core count, system or video memory, or screen resolution. It can also involve fingerprinting artifacts of the specific VM.

When building a sandbox, vendors have a large number of VM solutions to choose from, such as KVM, VirtualBox and Xen. Each one has various artifacts and idiosyncrasies that are detectable by software running in VMs underneath them.

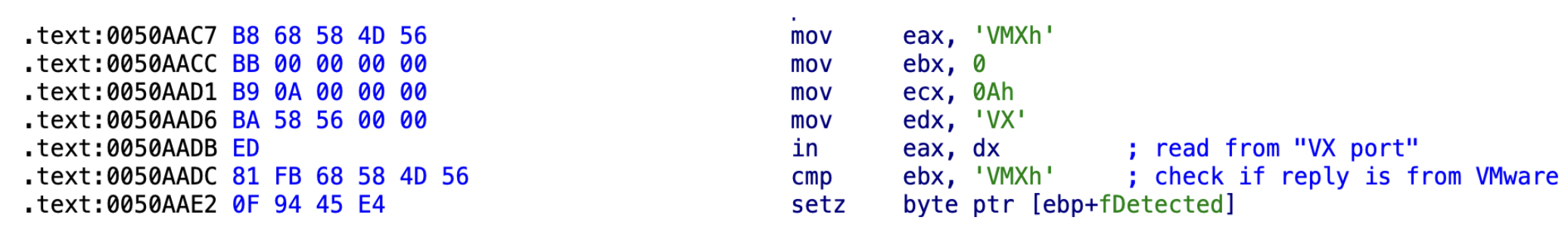

Some of these idiosyncrasies are particular to a specific system, like checking for the backdoor interface of VMware, or checking whether the hardware presented to the OS matches the virtual hardware provided by QEMU. Other approaches can simply detect hypervisors in general. For example, Mark Lim discussed a general evasion for hypervisors in an article, which capitalizes on the fact that many hypervisors incorrectly emulate the behavior of the trap flag.

One of the earliest and most widely used mechanisms for malware to determine whether it’s running inside a VMware virtual machine is to use the backdoor interface of VMware to see whether there is any valid response from the VMware hypervisor. An example of such a check is shown in Figure 4.

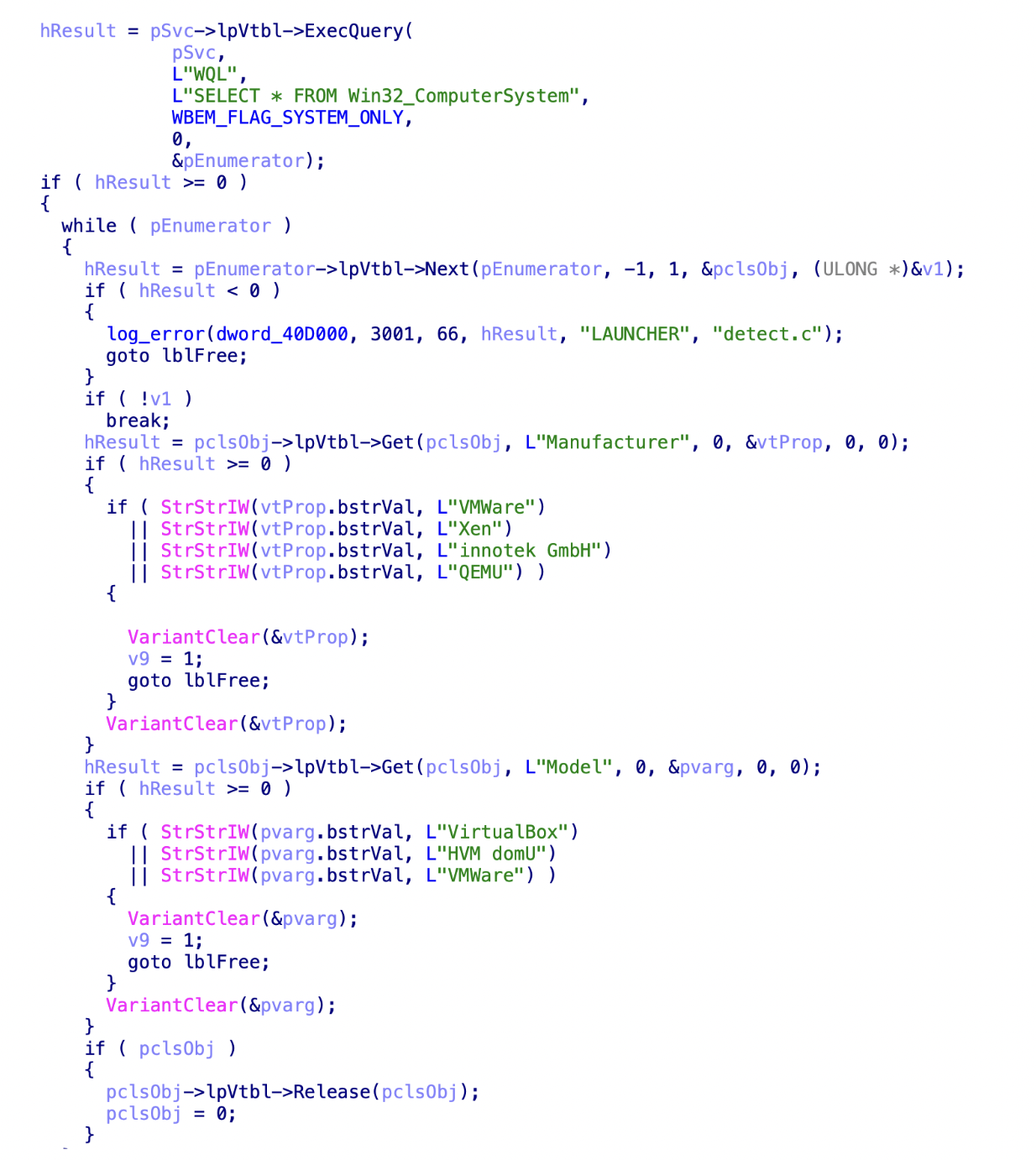

Malware families can also query the computer manufacturer or model information using Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) queries. This allows them to get information about the system and compare it with known sandbox and/or hypervisors strings.

Figure 5 shows how this is used to query against VMware, Xen, VirtualBox and QEMU. The same technique can also be found in Al-Khaser, which is an open-source tool that contains many anti-sandbox techniques.

Figure 6 shows the software components that malware can potentially interact with, to reveal whether it’s executing in a virtual environment.

Additionally, there is also often a great deal of information sprinkled around the guest VM that can easily provide clues as to what VM platform the guest OS is running underneath. In all cases, the specifics are dependent on the VM infrastructure used (e.g., VMware, KVM or QEMU).

The following are just a few examples of what malware authors can check for:

- Registry key paths showing VM-specific hardware, drivers or services.

- Filesystem paths for VM-specific drivers or other services.

- MAC addresses specific to some VM infrastructures.

- Virtual hardware (e.g., if a query reports that your network card is an Intel e1000, which hasn’t been made in many years, it can infer that you’re probably running with the Qemu hardware model).

- Running processes showing VM platform-specific services to support paravirtualization, or systems for user convenience like VMware tools.

- CPUID instruction that will, in many cases, helpfully inform software of the guest of the VM platform.

Mitigating VM Evasions

The main issue with most of these mitigations is that the mainstream virtualization platform alternatives are well known to malware authors. For ease of implementation, most sandboxes are based on systems like KVM, Xen or QEMU, which makes this class of evasions particularly tricky to defeat.

Every mainstream VM platform out there has been targeted by sandbox evasions. The problem is that nothing short of writing your own custom hypervisor to support malware analysis would effectively address this class of evasions.

… So that’s what we did!

Our detection team made the decision years ago to implement our own custom hypervisor tailored specifically for malware analysis. The dev teams went to great lengths to build (from scratch!) our own virtualization platform for dynamic analysis.

This decision has two advantages. The first is that we are not susceptible to the same fingerprinting techniques that are used against other VM infrastructure. We do not have any backdoor interfaces, but we do have different virtual hardware and a completely different codebase.

The second advantage is that, because we have built our own system, it is easier for us to adapt and address issues wherever we see malware using trickery on us for evasion purposes. For example, the linked article mentioned earlier discussed how many hypervisors incorrectly emulated the trap flag for guest VMs. Our malware analysts were able to close the loop with our dev teams to ensure that we emulated correctly and were not susceptible.

Lack of Human Interaction

This category includes evasions requiring specific human interaction. For example, a malware author would expect to see mouse clicks or some other event that would happen on a system with a “real” user driving it, but this would be absent in a typical automated analysis platform. Malware families often check for human interaction and cease execution if it looks like there is no user driving the system, because user activity is being simulated.

The following are the general themes we’ve observed for human interaction checks:

- Prompting users for interaction. For example, dialogue boxes or fake EULAs that a sandbox might not know should be clicked to ensure detonation.

- Checking for mouse clicks, mouse movement and key presses. Even the locations of mouse events or timing of keystrokes can be analyzed to determine whether they look “natural” versus programmatically generated.

- Placing macros in documents to check for evidence of human interaction like scrolling, clicking a cell in a spreadsheet or checking a different worksheet tab.

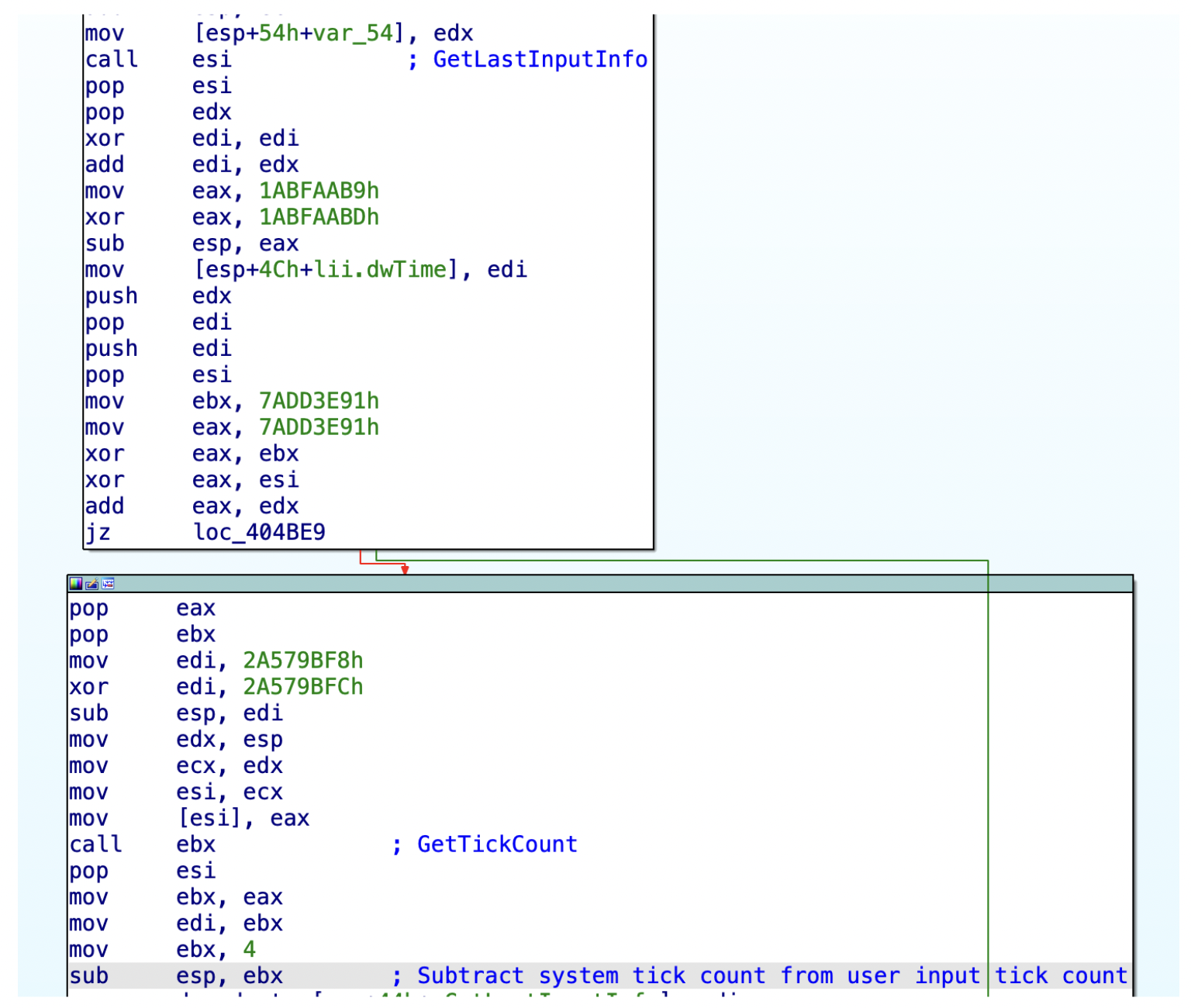

Let’s take a look at a specific example (shown in Figure 7) of how malware might get the time elapsed since last user input (GetLastUserInput) and the time elapsed since the system has started (GetTickCount). It can then compare how much time has passed since the last key was pressed, to detect if there is any activity on the system.

Mitigating Human Interaction Evasions

When implementing a sandbox, we have control of the virtual keyboard, mouse and monitor. If for some reason the analyzed executable requires any input keys, we can send key presses to the analysis, or make sure to click the correct button to continue the execution of the executable. It’s really just a question of knowing how to automatically do what a human would do to put on a convincing show for the malware we’re executing.

Like with all the other areas of the VM detection problem, we need to remain vigilant to what malware families are looking for, and continually improve our evasion strategy. A recent example involved malware that required individual mouse clicks on multiple cells within an Excel spreadsheet. We had to go the extra mile to ensure that we had a solid recipe for detection in place, in case this was used against us in the future.

Timing and Computing Resource Evasions

Early on, one of the most common sandbox evasions was to just call sleep for about an hour before doing anything evil. By doing this, it would guarantee that the malware would be well beyond the short analysis time window used by almost all sandboxes, as it’s not feasible to run every sample for more than a few minutes.

The reaction to this by sandbox authors was to instrument sleep to shorten any long sleeps to small ones. After many more iterations of this cat-and-mouse game, we now have a staggeringly diverse set of ever-evolving ways for malware to waste time in sandboxes and thus prevent any meaningful analysis results.

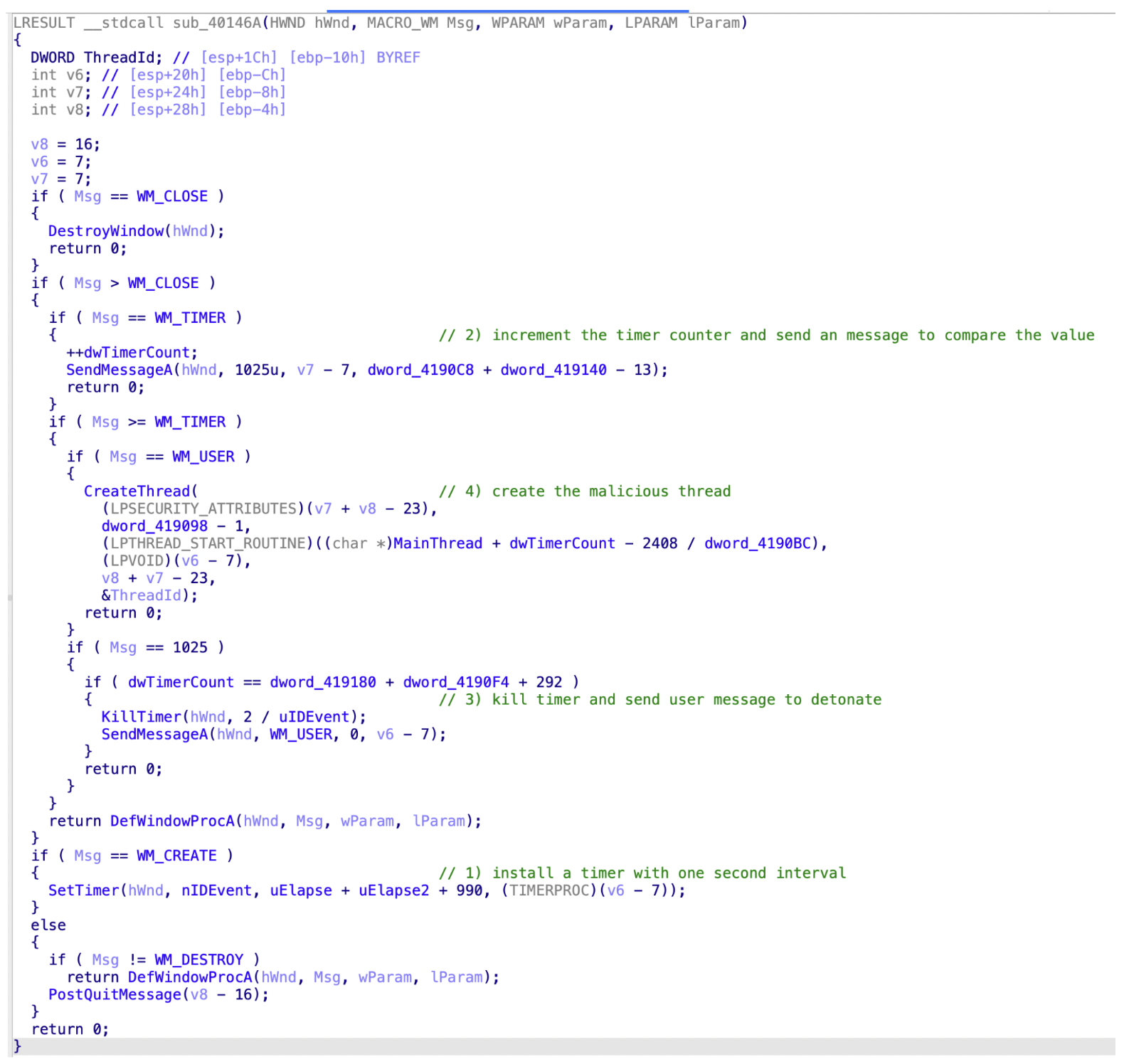

Figure 8 shows one evasion technique using Windows timers and Windows messages. The idea is to install a timer that will be fired each second, which then increments an internal variable when it’s executing the timer’s callback.

Once the variable hits a specific threshold, it will send another Windows message to notify the sample to start the execution of the malware. The problem with this evasion is that sandboxes can’t simply reduce the timer's timeout to a low number because it might break execution for other software, but it still must be executed somehow.

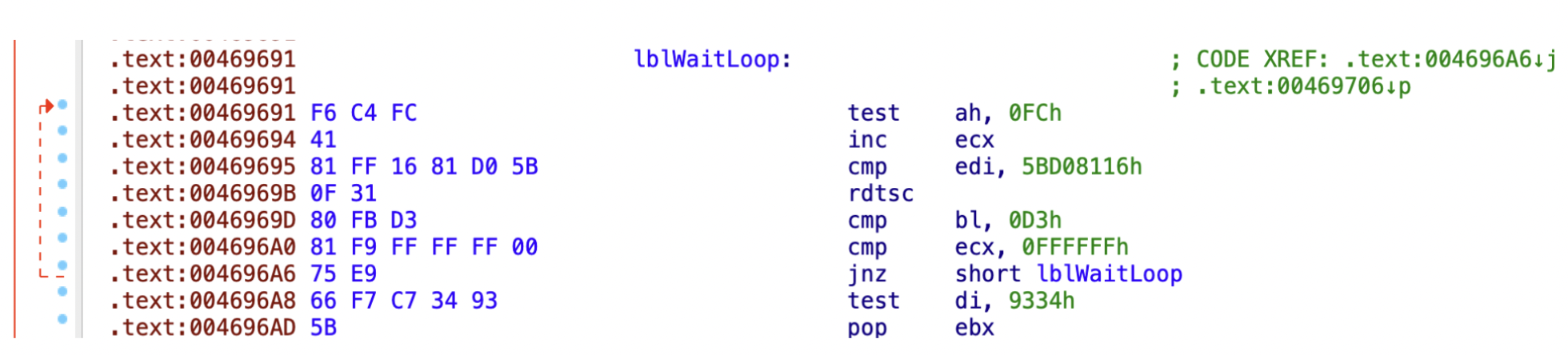

Another example is shown in Figure 9, below, where the malicious executables simply call the time stamp counter instruction in a loop.![]()

Timing Evasion Mitigations

Timing evasions can be very difficult to counter, depending on the situation. As previously mentioned, we can always adjust sleep arguments and timers but this does not completely solve the problem.

Another strategy that we’ve found useful is that, because we control the hypervisor, we can use techniques to control all hardware and software to make time move faster inside the guest VM. It’s even possible to do this without having to change arguments or install any hooks. We can run executables for an hour within minutes in real time, which allows us to reach the malicious code faster.

Junk instruction loops or VM exit loops are probably the hardest scenario to counter. If a malware author executes a few million CPUID instructions, which take exponentially longer to perform underneath a hypervisor, it’s a dead giveaway that our code is running in a VM. This is another situation where having a custom hypervisor tailored for malware analysis is useful, because we can detect and log this kind of activity.

Pocket Litter Checks

The term “pocket litter” has been co-opted from the field of espionage, where the items in one's pocket can be used for “confirming or refuting suspects' accounts of themselves.” This is a term we’ve internally adopted for all evasions in which malware authors are checking to see if the environment shows evidence of being a real, targeted host.

In terms of sandbox environments, checking for “pocket litter” commonly includes looking for things like a reasonable amount of system uptime, a sufficient number of files in the My Documents folder or a good number of pages in the system’s browser cache. These are all things that would help corroborate that the system is “real” and not a sandboxed environment. Like with the other categories, the number of variations are seemingly infinite.

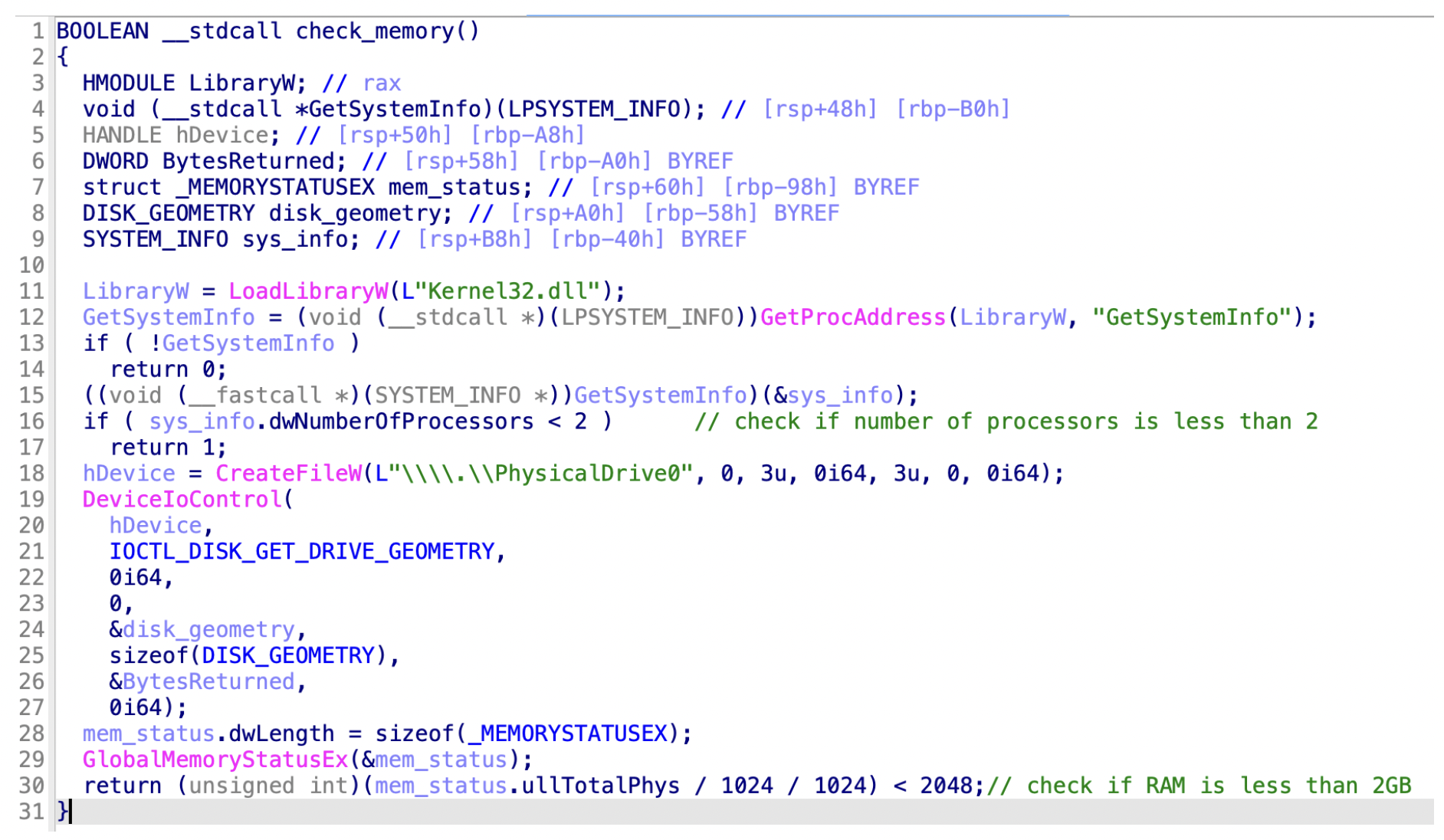

Figure 10 shows another example where the malware checks if there are more than two processors available and whether there is enough memory available. Usually sandbox environments don’t have as much memory available as regular PCs, and this check is testing whether the target system is likely to be a desktop PC or running inside a sandbox environment.

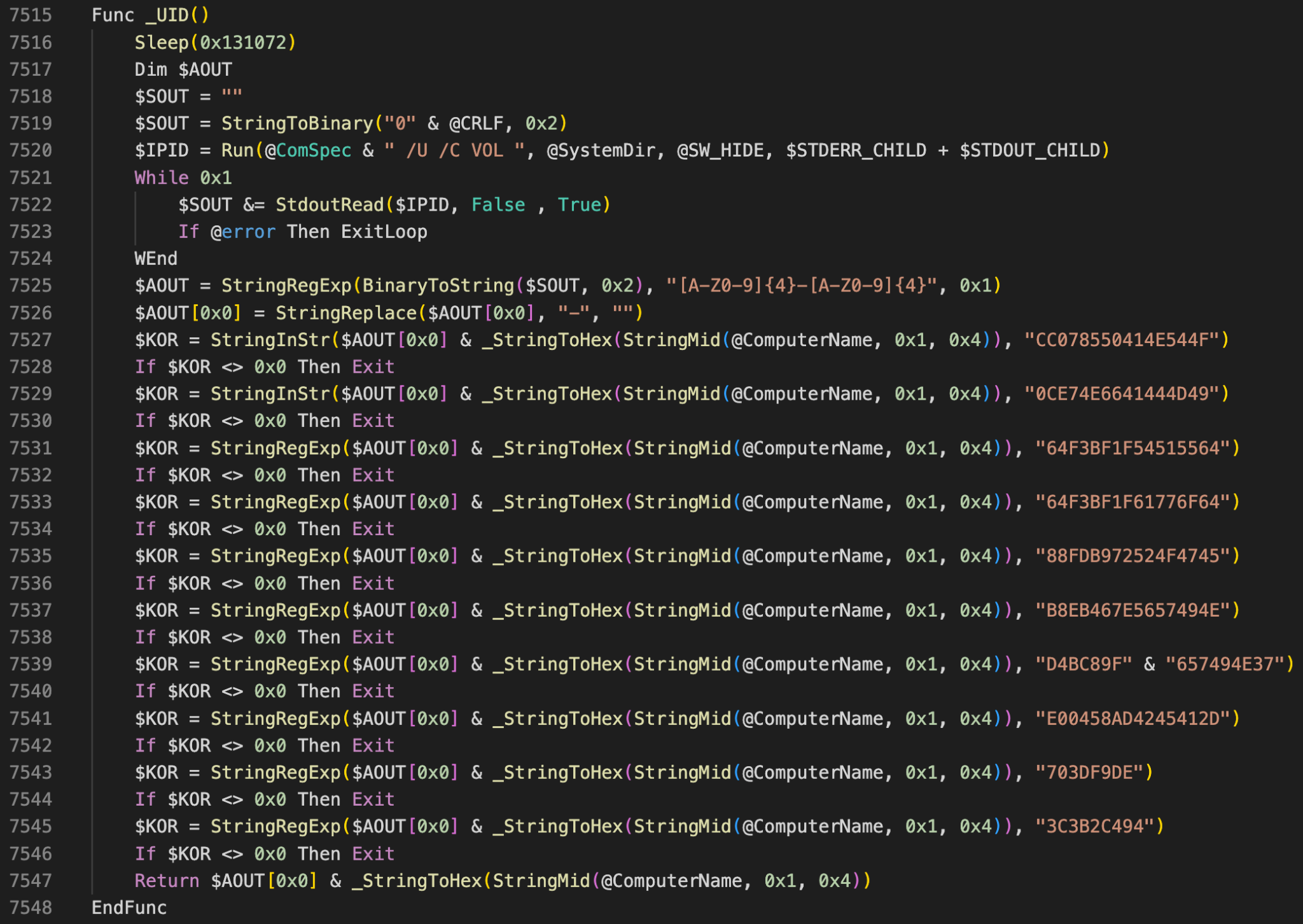

In Figure 11, there is another example where an AutoIt executable exits if the volume disk serial numbers match those of emulators used by known antivirus vendors.

Pocket Litter Check Mitigations

In terms of mitigations, there is no single broad stroke that can be used to cover all available techniques. Rather, we attempt to address these on a case by case basis, where we can.

For example, when we see checks for specific types of files in particular places being used by evasions (if it appears to be an innocuous change to the VM image) we add them for any related samples to see. This pocket litter approach can feel like a cat and mouse game because there really is no panacea that addresses all threat actor mice. Persistence is key.

Conclusion

We emphasize that we are in no way claiming to have “solved” all sandbox evasions. In fact, the situation is quite the opposite when you consider that evasion classes are more or less infinite.

If there is a single takeaway from our discussion, it is that there are too many sandbox evasions out there to effectively address every single one. Anyone who tells you their sandbox is 100% evasion-proof is overdue for a run-in with reality.

We have discussed some of the high-level category evasions in broad strokes, as well as some of the strategies we’re using to address them. Because we can’t come close to addressing them all comprehensively, we recommend a defense-in-depth strategy. This allows us to architect detection systems in such a way that we can still detect malware when an evasion is successful and there is no execution of the payload.

For us on the WildFire team, this means a departure from simply relying on system API calls and other observable activity as the sole basis for detection. Because we have our own hypervisor, we have been able to utilize our control of all hardware/software to instrument software in the VM in a way that is invisible to the malware that is running.

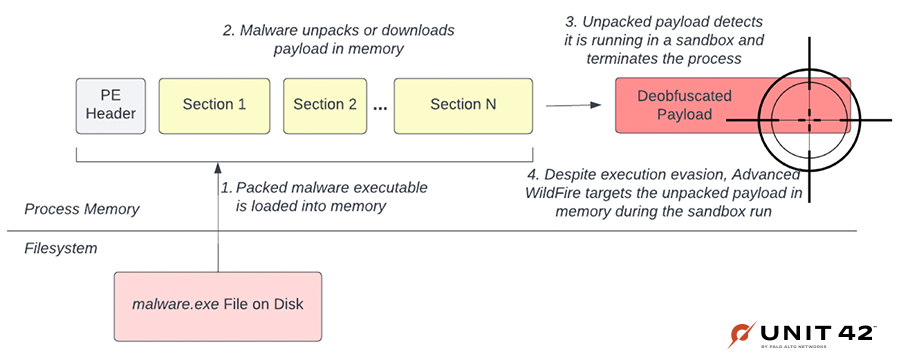

As we discussed in our previous post on hypervisor memory analysis in Advanced WildFire, our goal is to make a new kind of analysis engine that targets malware in memory. For any evasion technique discussed here, the code to execute it must, at some point, exist in memory in order for it to execute and then successfully detect it is being analyzed.

In our system, we’ve shifted detection focus to the deltas in memory during execution. As shown in Figure 12, if the payload or any code is decoded, decompressed or decrypted in memory, our system will have visibility and a solid chance at catching it.

In closing, our advice to anyone building out an automated malware analysis system is to be as flexible as possible in terms of reacting to the broad categories of sandbox evasions out there. It is guaranteed that you will run into many variations of the themes we discussed here.

We also recommend that you architect your system in a way that is tolerant to sandbox evasions. In other words, when all else fails and there are no execution events to scrutinize for malicious behaviors, there should be additional methods to fall back on. An example of what this looks like in practice is how we can analyze memory in Advanced WildFire to detect evasive malware even when payloads choose to remain dormant and not execute.

Thanks for joining us on this odyssey as we toured all of the ways malware authors go out of their way to avoid detection. Happy hunting!

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protections from threats such as those discussed in this post with Advanced WildFire.

Indicators of Compromise

| SHA256 | Description | Malware family |

| 3bf0f489250eaaa99100af4fd9cce3a23acf2b633c25f4571fb8078d4cb7c64d | WMI queries | Trickbot |

| e9f6edb73eb7cf8dcc40458f59d13ca2e236efc043d4bc913e113bd3a6af19a2 | Timing attack using SetTimer | Sundown payload |

| 3450abaf86f0a535caeffb25f2a05576d60f871e9226b1bd425c425528c65670 | Sleep using time stamp counter instruction | VBCrypt |

| 091ffdfef9722804f33a2b1d0fe765d2c2b0c52ada6d8834fdf72d8cb67acc4b | Volume Disk serial number check | Zebrocy |

| SHA256 | Description | Potentially unwanted applications |

| 96a88531d207bd33b579c8631000421b2063536764ebaf069d0e2ca3b97d4f84 | VMware check | PUA/KingSoft |

| de85a021c6a01a8601dbc8d78b81993072b7b9835f2109fe1cc1bad971bd1d89 | GetLastUserInput check | PUA/InstallCore |

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42