In recent years, there have been a number of high-profile stories involving the compromise of point of sale (PoS) devices. My research often involves deep reverse engineering and analysis of various malware families targeting PoS devices. As such, I’m often asked about the overall threats that these machines face. In this article I hope to provide a high-level view of the threat landscape currently affecting PoS devices.

Background

The term PoS refers to a machine used by businesses to conduct a retail transaction. If you have ever used a debit or credit card to make a purchase, you’ve likely seen these machines. They often run customized hardware and software, however, the underlying operating system (OS) is more commonly some version of Microsoft Windows, often Windows XP or Windows 7. This trend has shifted slightly in recent years with the popularity of mobile PoS devices, most of which run either Android or iOS. While these are becoming more common in smaller businesses, Windows-based PoS machines still make up the majority, and by association are the devices most heavily targeted by attackers.

Figure 1. Example PoS machine

Infiltration

While PoS devices can be attacked in many ways, the method of infiltration typically falls into one of the following three categories, listed by least sophisticated to most sophisticated:

- Spam emails / Exploit kits

- Scanning the Internet for default or common credentials

- Compromising trusted third parties

Spam Emails / Exploit Kits

These types of attacks are widespread and are often leveraged by attackers who are looking to infect as many machines as possible. Botnet owners are often seen leveraging these attacks to add further devices to their botnets.

Unfortunately, a number of organizations that own PoS machines use them as they would a personal computer. They browse the web, check email, and conduct day-to-day operations from the same machine that is conducting financial transactions. Attackers discovered that while infecting a large number of machines on the Internet, they were also infecting a small number of PoS devices as well. One such example of how PoS devices can be misused was demonstrated on Reddit, where a user discovers that he/she can access the site on their PoS. While accessing this site alone does not pose any significant security issues, it demonstrates how PoS devices can be misconfigured to allow users to access websites and Internet-based resources that should be blocked. Because of the lack of security controls on these devices, spam emails and exploit kits are able to infect these machines and subsequently steal financial data from them.

Internet Scanning for Default or Common Credentials

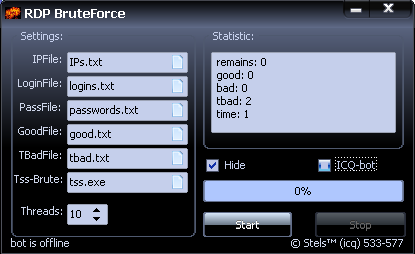

While more common in past years, this particular type of threat still represents a portion of attacks against PoS machines. Many PoS vendors configure their devices with remote administration services, such as Microsoft Remote Desktop, VNC, pcAnywhere, or LogMeIn. These services allow vendors to update and configure PoS machines remotely. As PoS machines may be located in geographically diverse regions, this is commonly built-in as a necessity.

Unfortunately, these services are often are configured to communicate and be accessible directly from the Internet, which allows both administrators and attackers alike to connect and attempt authentication. Additionally, these remote management services are frequently configured with default usernames and passwords. Knowing these combinations of usernames and passwords, attackers will continually scan the Internet in the hopes of identifying systems that can be accessed in such a way. A number of free utilities are available online that are designed for such tasks, making it trivial for individuals online to identify and subsequently compromise misconfigured PoS machines described.

At a recent RSA conference, researchers unveiled that a major PoS vendor had included a default username and password for all of their products for roughly 25 years. Misconfigurations such as these by both vendors and those configuring PoS machines allow attackers to obtain unauthorized access.

Figure 2. Example Remote Desktop brute force login tool

Compromising Trusted Third Parties

In one of the most sophisticated techniques seen to date, attackers have begun targeting trusted third party organizations in order to gain access to PoS machines. This trend has been seen in recent years, with the Target breach being the most well known example. In that particular instance, an intrusion at the organization’s HVAC contractor was used to gain access to Target’s PoS machines.

Additional third party organizations, such as point of sale integrators, have been increasingly targeted in the past two years. PoS integrators are organizations responsible for the installation and maintenance of PoS machines for their clients. These organizations are often the victim of targeted attacks where spear-phishing emails and other ploys are used to compromise their networks. Once compromised, the attackers use stolen credentials, as well as the trust of the integrators networks to pivot and compromise PoS machines on their client’s networks. This tactic has been deployed heavily by the attackers behind the Backoff PoS malware family, impacting over one thousand US-based companies in 2014.

Malware Types

PoS malware is described in four categories:

- Network Sniffer

- File Scraper

- Keylogger

- Memory Scraper

Due to improvements in both PCI regulations as well as general security surrounding PoS machines, network sniffers and file scrapers are rarely, if ever, seen today. Not only did network sniffers provide track data sent across the network unencrypted, but they also had the ability to extract other sensitive information, such as credentials sent across the network. Such information could be used by attackers to gain access to other systems on the network. Alternatively, file scrapers had similar abilities, where both card data and other sensitive data on the victim machine could be identified and subsequently used by attackers. From 2007 to 2009, especially, these types of malware families were prevalent.

Since then, keyloggers and memory scraping malware families have become commonplace in PoS breaches. Keyloggers can work in a number of ways, however, one of the most common ways is to create a message-only window via a call to CreateWindow. The malware will then register a new input device via a call to RegisterRawInputDevices, which is in turn used to capture keyboard input data. Additionally, keyloggers will often also capture screenshots of the desktop to provide the attacker with more information about the victim machine.

Figure 3. Example of malware implementing keylogging functionality

Memory scrapers typically work in a small number of ways. They will begin by obtaining a handle to a process that the malware wishes to target. These processes are typically discovered via calls to either CreateToolhelp32Snapshot or EnumProcesses. At this particular stage, memory scrapers will often employ either a denylist approach, where common process names are ignored, or an allowlist approach, where only a small subset of known process names are targeted. As an example, the svchost.exe process might be ignored, while the frmweb.exe process might be targeted.

Once a process is identified and a handle is obtained, memory scrapers will iterate through pages of memory using the VirtualQuery function. Further checks are often performed during this particular stage. Namely, a good memory scraper that is targeting track data will typically only look at pages that are set with read/write permissions and has a state of MEM_COMMIT. This allows the malware to ignore free or reserved memory, or memory that contains code, which in turn will improve performance.

After a page of memory is identified, the malware will actually read it via a call to ReadProcessMemory. After the memory has been read into a buffer, it will commonly apply a regular expression against this data, or feed the buffer to a function that is responsible for identifying track1 and track2 data. An example of some regular expressions witnessed in the wild can be seen below:

- \d{15,19}=\d{13,}

- \?

- ((B(([0-9]{13,16})|([0-9]|\\s){13,25})\\^[A-Z\\s0-9]{0,30}\\/[A-Z\\s0-9]{0,30}\\^(0[7-9]|1[0-5])((0[1-9])|(1[0-2]))([0-9]|\\s){3,50})|(((37)|([4-5][0-9])|(60))[0-9]{13,14}(D|=)(0[7-9]|1[0-5])((0[1-9])|(1[0-2]))[0-9]{8,30}))

- ((b|B)(([0-9]{13,16})|([0-9]|\s){13,25})\^[A-Za-z\s0-9]{0,30}\/[A-Za-z\s0-9]{0,30}\^(0[7-9]|1[0-5])((0[1-9])|(1[0-2]))([0-9]|\s){3,50})

- ([0-9]{15,16}(D|=)(0[7-9]|1[0-5])((0[1-9])|(1[0-2]))[0-9]{8,30})

As we can see, the regular expressions used by memory scraper authors vary in complexity and effectiveness. For instance, the initial regular expression listed above is used to identify the primary account number (PAN) for a given user. Alternatively, the second regular expression simply looks for the character ‘?’, which will match on any number of strings. Thus, the ability to gather accurate results will vary based on what particular regular expressions an author chooses.

In addition to some of the other checks performed, a luhn check may be performed in order to validate the data that is identified.

After track data has been identified, it may be written to a dump file, or automatically exfiltrated using a network protocol. HTTP, HTTPS, SMTP, and FTP are the most common protocols witnessed.

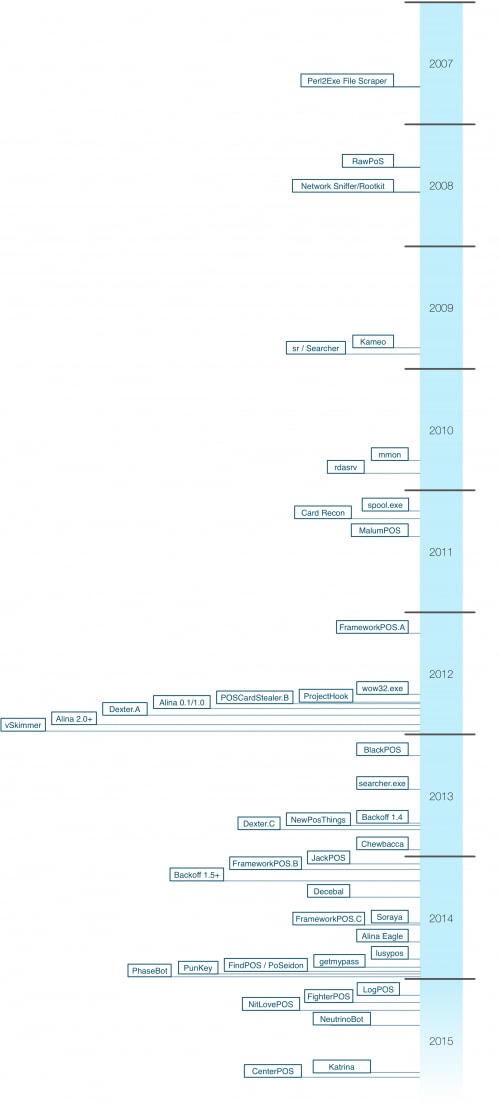

Malware Trends

Over the past decade, malware targeting PoS devices has evolved and changed considerably. The following diagram outlines the malware families witnessed during this time.

Figure 4. Timeline of PoS malware families

2007-2008

While attacks against PoS devices took place before 2007, this was the earliest indication of custom malware being written specifically targeting them. During this early period of 2007-2008, custom malware was fairly rare. Many security protections were simply not implemented during this time. PoS devices often didn’t encrypt network traffic, and stored card data was kept on the filesystem, commonly unencrypted. Because many of these lacked security controls, attackers would simply employ tools that were used by security professionals on a daily basis, such as wireshark, tcpdump, find, and grep to name a few. Additionally, the use of file scrapers and network sniffers were very common.

There are some reported incidents where an attacker gained access to a PoS system only to discover a text file on the desktop with years’ worth of transaction records. In such cases, malware is often unnecessary, as the attacker can simply download the file in question and return periodically for any updates.

However, some malware families emerged during this time, such as the infamous RawPOS malware family. While this particular family gained much notoriety in 2014, it was actually one of the first known memory scrapers used in PoS attacks. The malware families created during this period varied in their techniques but shared many commonalities. For example, these malware families often provided minimal automation in the form of data exfiltration. They would instead write results to a dump file on the victim device’s file system.

It’s also important to note that the media does not often mention attacks hitting PoS devices during this period, and aren’t well known to the public.

2009-2010

Toward the end of the decade, the emergence of memory scrapers and keyloggers continued. As security controls improved, we saw very few instances of file scrapers or network sniffers. During this period, we also saw the appearance of some malware families that were witnessed for many years afterwards -- namely, the rdasrv, mmon, and sr/searcher malware families. These families are all memory scrapers that are often incorporated into other malware families in later years. Like the 2007-2008 period, this malware was very specific in its approach, providing no automatic exfiltration or control capabilities. The approach of attacking PoS devices was still considered a very manual endeavor in 2009-2010, as attackers needed to identify processes handling card data, and then target said processes using the malware at their disposal.

2011-2012

The 2011-2012 period for PoS attacks brought several interesting developments. The use of CardRecon, a commercial PCI compliance tool, was discovered in a number of breaches. Attackers used an illegally obtained copy of this program in order to identify card data being stored on the PoS file system. We also saw the first instance of FrameworkPOS, which is one of the more advanced malware families seen to date. FrameworkPOS not only provided automatic exfiltration, but it also heavily obfuscated data stored within the registry, and was highly targeted towards the victim. The group behind this particular malware family would be continually seen in the following years, often compromising very large organizations.

Generally, the use of automatic exfiltration continued to become more common among malware families in 2011-2012. During this time, the use of SMTP and FTP were frequently observed. However, by using these network protocols, the malware authors were forced to include authentication credentials within the malware itself. This of course causes a problem, as a malware analyst has the ability to extract this data from the binaries. In subsequent years, malware authors corrected these mistakes and shift towards other network protocols, such as HTTP and HTTPS.

Toward the end of 2012, we saw some very interesting developments within the PoS malware community. Namely, the release of the Dexter and Alina malware families that caused quite a stir due to their more advanced features. Both Dexter and Alina emerged around the same time, and provided not only automatic exfiltration capabilities, but a command and control (C2) component as well. This allowed attackers to deploy their malware to multiple locations and control the victims from a single C2 administration panel. This had not been witnessed previously, and added an automation to PoS attacks that was not seen prior.

During this period, we also started to see increased media attention on the topic of PoS breaches and malware families. A number of high-profile breaches gained the attention of both the general public and malware authors alike.

2013-2014

The emergence of Dexter and Alina caused quite a stir in the PoS malware community, and many authors took notice. As such, a number of malware families were written with C2 characteristics in 2013-2014, such as vSkimmer, JackPOS and Backoff.

In mid-2013, the source code to the Alina malware family was sold in underground forums for $2,000. This code eventually leaked in the criminal underground shortly afterwards. Roughly two weeks after the announcement of Alina’s source code sale, in an unrelated incident, the source code to the first major variant of Dexter was leaked on the popular underground forum Darkode. The sale/leak of such prominent PoS malware families caused a number of authors to reuse and modify this code. Because of this, a number of new families were subsequently created and used, such as Spark, Eagle, and getmypass. This trend continues to this day.

The high prevalence of malware families using command and control allowed malware authors to essentially create botnets out of infected PoS devices. As such, it wasn’t long before botnet malware authors took notice. Botnets, such as Andromeda, have been used often to distribute PoS malware families, such as Alina and JackPOS. However, other botnet authors began to implement PoS modules directly in their malware, such as Phase.

2015

This trend of adding PoS memory scraping modules to existing botnets continued into 2015. One such example is the Neutrino bot, which features denial of service commands, anti-reversing characteristics, keylogging functionality, and a command shell.

Other than the continued emergence of botnets implementing PoS features, 2015 has had minimal new PoS malware families emerge. It is likely that there simply hasn’t been a need or demand for new malware families, as a number of the more established malware families are continually updated and are successful in their endeavors.

Aftermath

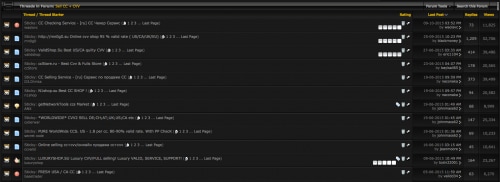

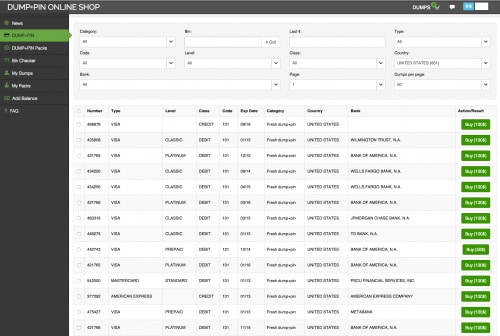

After an attacker has successfully acquired card data from a targeted merchant, they will most likely sell that data on an underground forum. There are many underground forums available today, specializing in both various services and geographic areas.

Many of the larger carders provide shops to sell their dumps, often with clean user interfaces and granular search options. Customer service and ease of use are very important to the owners of these shops, as a shop’s reputation will often be the deciding factor for an interested buyer.

After a number of cards are purchased, carders will clone physical cards with the data they’ve obtained or purchased. Individuals in the same underground forums will often provide services to create plastic cards. Some examples of these cards can be seen below. As we can see, they look quite convincing to an untrained eye.

These cards can then be used to make purchases by carders. In the event a debit card with a PIN has been obtained, cloned cards can be used to withdraw money at various automated teller machines (ATMs). Carders will often purchase high-end items with the intent of reselling them online. In doing so, they are able to essentially use credit cards to obtain actual cash.

Conclusion

Attacks targeting PoS devices have been occurring for many years, and show no sign up stopping in the near future. The universal rollout of “chip and pin” will likely deter traditional attacks facing PoS devices. This has been witnessed in Europe, where EMV technology has been widely adopted for a number of years. In such situations, the attackers typically change tactics. Instead of targeting PoS devices, attackers target e-commerce websites instead, dumping databases from these webservers and acquiring card data.

In general, intrusion techniques targeting PoS devices are often no different from techniques targeting other Internet or network-connected machines. The main difference lies in the payload, which these days are typically a keylogger, or much more commonly, a memory scraper. These payloads, or malware families, have evolved over time to become heavily automated. Such automation allows attackers to infect hundreds or thousands of machines at a time, and make changes at the click of a button.

Proper PoS Security

Those charged with the task of securing PoS devices should take necessary precautions in order to help prevent the theft of card data. Such precautions include, but are not limited to:

- Ensure PoS devices are not directly connected to the Internet. If required, proper controls should be enabled to only allow connections to specific hosts over specified network protocols.

- Web browsing should be disabled completely on PoS devices if possibly. If not possible, controls should be enabled that restrict browsing to specific websites.

- Prevent unauthorized users from installing or running executables on PoS devices using process allowlisting.

- Install security software, such as antivirus, on PoS devices.

- Update all necessary operating system patches.

- Implement network segmentation between PoS devices and other corporate infrastructure.

- Ensure any remote access applications, such as RDP, VNC, LogMeIn, etc. are configured with unique usernames and passwords, are fully up to date on patches, and are configured with 2-factor authentication if possible.

- Properly log host and network-based events.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42