This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

We're always working to find new ways to protect customers and prevent successful attacks, and one recent addition to our research arsenal is the use of unsupervised machine learning on large datasets of domain information. Machine learning-based techniques like this can help us discover new threats and block them before they can affect our customers. They can quickly identify malicious domains that are part of larger campaigns as soon as they become active and provide much broader coverage for these campaigns than traditional methods.

This blog gives some details and examples of how we are using this unsupervised machine learning. Specifically, in one recent phishing campaign, we found 333 active domains. On the first day of this campaign being active in the wild, only 87 domains were known to a popular online malware database and all were wholly unknown to two well-known block lists. In the following two weeks, the best performing block list only blocked 247 of the 333 domains and the malware database only recognized 93.

Our unsupervised machine learning expands total coverage of these campaigns and identifies them early, before they impact vulnerable users. In the case of the campaign discussed below and other campaigns detected using the same technique, Palo Alto Networks customers were protected within one day of the domains going live.

Background

One class of malicious online activity involves the use of many domains for the same purpose and for a short duration of time. These campaigns often take advantage of a recent topical event, like the World Cup, and the domain names often utilize typo-squatting of legitimate domain names or names that indicate some relevance to legitimate services, like c0mpany.com for company.com.

A previous example of this is the release of malicious campaigns after the Equifax data breach of 2017. In the case of the Equifax breach, the credit reporting agency set up a legitimate website, www.equifaxsecurity2017[.]com, to help people determine whether they had been affected. This triggered one or more malicious campaigns that registered hundreds of domains that closely mimicked the real URL. For example, www.equifaxsecurity3017[.]com.

It is generally easy to look closely at a single domain name and tell that it is fraudulent but, because hundreds of such domains can be created in a campaign, the challenge is finding all fraudulent domains before they start to impact a large number of people. While they have slightly different domain names, malicious domains belonging to the same campaign still share many common characteristics such as IP subnet, Autonomous System Number (ASN), DNS Time-To-Live (TTL), Whois information, and many other attributes. Based on this observation, we have implemented a system to extract attributes from DNS traffic and cluster domains based on their similarity. Our system complements existing methods and can identify campaign domains that might not be identified otherwise.

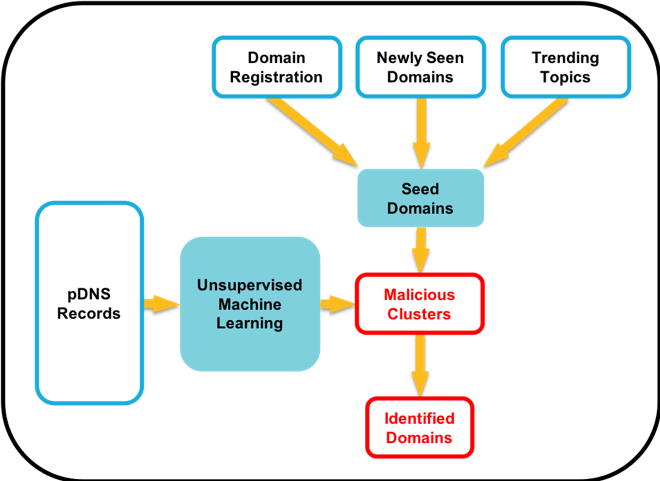

Figure 1: High-Level process

Approach

Our approach (see Figure 1) is to cluster domains that have been seen in passive DNS records. Passive DNS is a mechanism to record DNS query/response traffic. The records mainly consist of timestamp, the requested domain, and the corresponding IP address, among other pieces of data. For privacy reasons, DNS traffic from individual clients ("recursion desired" bit is set) is not captured and the client IP is also removed.

Passive DNS records are available from a variety of sources and are often used by researchers to understand Internet traffic at scale. There are generally more than 6 terabytes of passive DNS records available daily for our analysis.

We cluster these domains using features that have been generated from information in the passive DNS records, such as IP address, as well as other sources, like BGP and Whois. This provides us clusters of domains that are related to each other but are otherwise unlabeled as benign or malicious.

Because this data is unlabeled at this point, this is an application of unsupervised machine learning. We know that the domains that are grouped together share many common characteristics, but not whether they are malicious or not. To find the malicious clusters, we use seed domains that appear to be part of a new campaign and we have verified as malicious.

Seed Domains

Seed domains are examples of malicious domains that appear to show up in groups.

The seeds can be found in a variety of ways and we currently focus on three sources of information to identify candidate seed domains: Domain Registrations, Newly Seen Domains, and Trending Topics.

Domain Registrations

We look at domains that have been recently registered and find groups that have similar names. If the campaign is taking advantage of a recent event, then a large group of domains may be registered with a name corresponding to the event. We check any groups for known malicious domains and the results are placed in our list of seed domains. We identify known malicious domains based on our own detections as well as 3rd-party threat intelligence such as a popular online malware database. Many malicious domains may not be known or reported at this point, but we only need to find a few examples to start the process.

Newly Seen Domains

We also check for new domains in the passive DNS records that have never been seen before. These may have been registered long ago but not placed in service until the campaign was launched. We search these for groups of similar names and identify seeds from any that are known to be malicious.

Trending Topics

We also search social media for trending topics. If any well-publicized events occur, they will often show up in the daily social media trends. We cross-check trending words that are seen on Google or Twitter with recently seen domain names. For example, if we see a Google trend that relates to a recent event, like a sporting event, we check recently seen domains that also reference that sporting event. We again look for groups of similar names and check for any that are known to be malicious. With our list of seed domains, we are now ready to search for clusters of domains that contain these seeds.

Finding Malicious Clusters

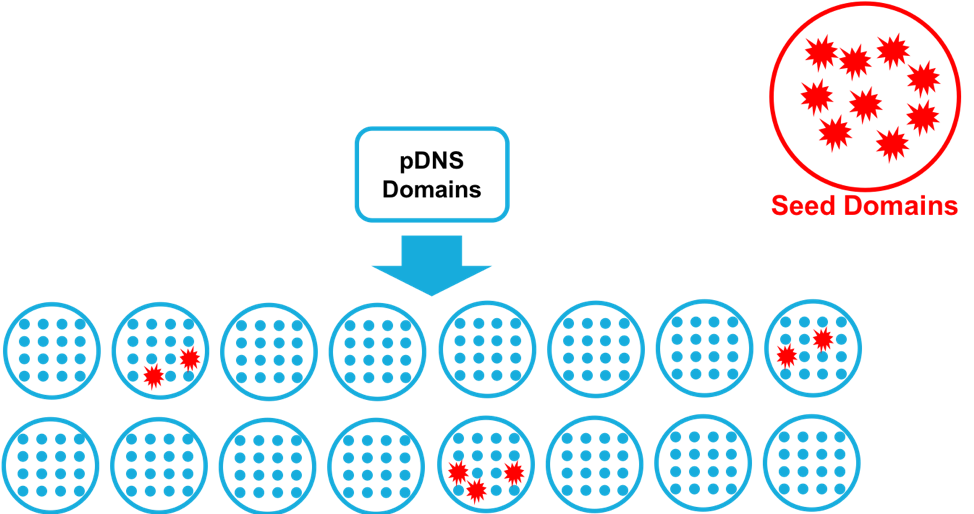

After we identify the group of seed domains we will use, we search for them among the clusters of domains that we previously calculated from the passive DNS data. (See Figure 2.) Any cluster with a significant percentage of seed domains is considered a malicious campaign and all domains in the cluster are marked as malicious.

Figure 2: Clusters of domains

Results

As an example, we recently discovered a phishing campaign that used malicious domains with names like check-box-with-money##[.]loan. We picked up this group of domains by observing a group of similar domains registered at the same time. On day one, we saw 77 domains registered. Of these, only 17 were known to a popular online malware database but this was enough to add them to our seed group. Through the clustering analysis of domains seen in passive DNS, we immediately saw 2 additional domains not seen from registration.

The following day, we found another 16 domains in the campaign, then 58 domains, and then 88 domains. In the first two weeks of this campaign, we found 333 domains that were associated with this phishing campaign.

More interestingly, of those 333 domains, we found that 247 of them were unknown to a popular online malware database on the first day that the domains were seen in the wild. In the subsequent two weeks, only 7 of those domains were eventually flagged. After two weeks, 240 domains were still not flagged as phishing by that database even though the domains were actively present on the internet and clearly part of the same campaign.

We also checked with two well-known blocklists. Of these blocklists, we found that neither had started blocking the domains on the first day that they were seen on the Internet. In the subsequent two weeks, of the 333 domains, one blocked only 80 of the domains and the other blocked 247.

These results highlight that even though some domains in the campaigns are found by the security community, it is easy for many of the domains to get through unblocked which is the ultimate goal of the attacker.

Conclusion

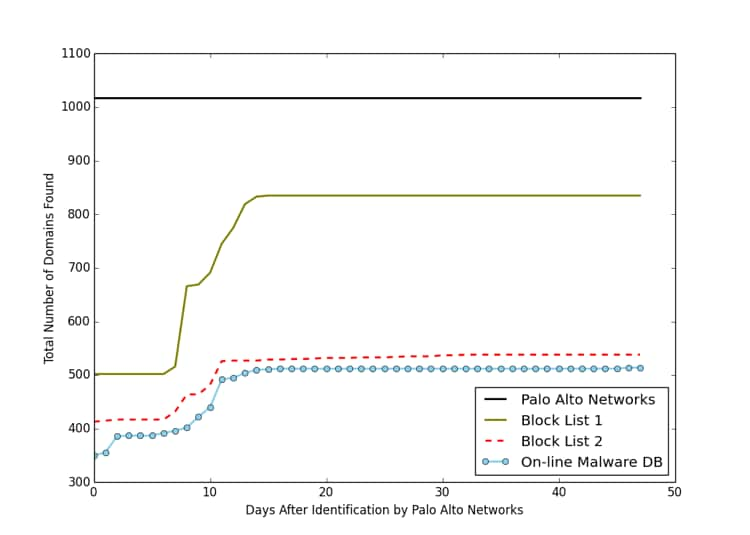

This is only one example. In the last two months, we discovered 15 distinct campaigns composed of over 1,000 active domains. Although active and part of the campaigns, many of those domains have not been individually identified by several popular 3rd party services. Of the domains that have been identified by a 3rd party service, we find the domains an average of 2.8 days before an online malware database, 3.9 days before one popular block list, and 2.4 days before another. The maximum deltas we have seen to date among the domains identified by 3rd parties are 46 days for the malware database, 15 days for the first block list, and 32 days for the second. Figure 3 shows the overall comparison of time to identification.

Figure 3: Time until identification by 3rd parties

Protection and Call to Action

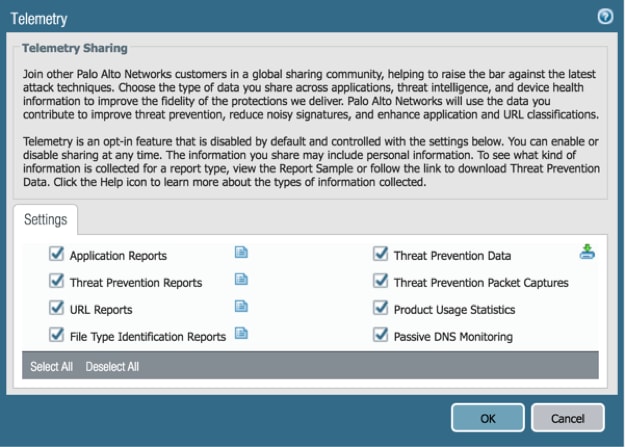

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected against these malicious and phishing domains through PAN-DB URL Filtering and DNS C2 signatures that are part of the Threat Prevention subscription. Palo Alto Networks firewall customers can help our passive DNS research to proactively find malicious and phishing domains. To enable passive DNS sharing in PAN-OS version 8.0 or a later release, select “Passive DNS Monitoring” (Device > Setup > Telemetry). For PAN-OS 7.1 or an earlier release, passive DNS sharing is enabled in the Anti-Spyware security profile. The passive DNS records mainly consist of timestamp, the requested domain, and the corresponding IP address, among other pieces of data. For privacy reasons, DNS traffic from individual clients ("recursion desired" bit is set) is not captured and the client IP is also removed.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42