While investigating a recent security incident, Unit 42 found a webshell that we believe was used by the threat actor to remotely access the network of a targeted Middle Eastern organization. The construction of the webshell was interesting by itself, as it was actually two separate webshells: an initial webshell that was responsible for saving and loading the second fully functional webshell. It is this second webshell that enabled the threat actor to run a variety of commands on the compromised server. Due to these two layers, we use the name TwoFace to track this webshell.

During our analysis, we extracted the commands executed by the TwoFace webshell from the server logs on the compromised server. Our analysis shows that the commands issued by the threat actor date back to June 2016; this suggests that the actor had access to this shell for almost an entire year. The commands issued show the actor was interested in gathering credentials from the compromised server using the Mimikatz tool. We also saw the attacker using the TwoFace webshell to move laterally through the network by copying itself and other webshells to other servers.

Actor Activities using TwoFace

The web server logs on the system we examined that was compromised with the TwoFace shell gave us a glimpse into the commands the actor executed through their malware. These commands also enabled us to create a profile of the actor, specifically their intentions and the tools and techniques used to carry out their operation.

Our analysis determined that five different IP addresses from four countries issued commands on the TwoFace shell, as seen in Table 1. As it is possible these originating IP address may themselves have been targeted and compromised, we have redacted the full IP addresses to hide the identities. The first command in the logs was issued on June 18, 2016, which was a simple “whoami” command to get the username on the server. This single command was the only one by this specific IP address which appears to be in Iran, and suggests that the actor may have initially compromised the server around this time and performed a quick check to see if the shell was loaded successfully.

| IP address | Country | Number of Commands | Date of Activity | Days Since Initial Command |

| 46.38.x.x | Iran | 1 | 2016-06-18 | 0 |

| 178.32.x.x | France | 6 | 2016-09-28 | 103 |

| 137.74.x.x | France | 16 | 2017-03-03 | 259 |

| 192.155.x.x | USA | 61 | 2017-04-24 | 311 |

| 46.4.x.x | Germany | 10 | 2017-05-03 | 320 |

Table 1 IP Addresses seen issuing TwoFace Commands

Three months after this single, initial command the next set of commands were sent. This time on September 28, 2016 a series of twelve commands were sent from an IP address apparently in France. These commands provide additional insight into the actor’s intentions. It is not certain why a time gap exists in issuing commands to the TwoFace webshell, although it is highly plausible this may simply be a visibility gap or even anti-detection measure taken by the actor. Rather than speculating on this gap and subsequent time gaps between interactions, we will focus on the commands actor issued that provide insight into this actor’s tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs).

The first command issued from this second IP address attempts to run a variant of the Mimikatz post-exploitation tool (m64.exe), specifically the Sekurlsa module that gathers the passwords of accounts currently logged into the system and saves the results locally to a text file. The actor then issues a command that uses the “type” command to read the contents of the text file containing the passwords, followed by a command that uses “del” to delete the text file.

c:\windows\temp\m64.exe privilege::debug sekurlsa::logonpasswords exit > c:\windows\temp\01.txt

Just over five months later on March 3, 2017, a third IP address, a different one apparently in France, issued a series of 16 commands to the TwoFace webshell. The first command of interest is as follows:

net group "Exchange Trusted Subsystem" /domain

According to MSDN, the “Exchange Trusted Subsystem” group is defined as follows:

The “Exchange Trusted Subsystem” is a highly privileged universal security group (USG) that has read/write access to every Exchange-related object in the Exchange organization. It’s also a member of the Administrators local security group and the Exchange Windows Permissions USG, which enables Exchange to create and manage Active Directory objects.

Using hostnames obtained from the previous command, the actor issues several commands to determine if they have access to Microsoft Exchange related folders. The actor then issued several commands that attempt to copy a different webshell onto these additional systems, which resembles the following:

copy c:\windows\temp\Exchange.aspx "\\[hostname]\d$\Program Files\Microsoft\Exchange Server\V14\ClientAccess\exchweb\ews\"

This clearly shows the threat actor attempting to use the TwoFace webshell to pivot to other servers on the network. The “Exchange.aspx” file copied over to the other systems appears to be a different webshell from TwoFace. We analyzed this additional webshell and have named it IntrudingDivisor, which we will describe in detail later in this blog.

On April 24, 2017, a fourth IP address, this one apparently in the United States, issued 61 commands to the TwoFace webshell. Like the previous set of commands issued in March 2017 from France, this IP address issued the command to obtain objects in the Exchange Trusted Subsystem group, and it appears the actor copied over yet another webshell named “global.aspx” and set the file’s attributes to be hidden using the following command:

attrib h "\\[hostname]\d$\Program Files\Microsoft\Exchange Server\V14\ClientAccess\exchweb\ews\global.aspx"

The actor then issued commands that suggests the use of the Mimikatz tool, but this time Mimikatz was named “mom64.exe” instead of “m64.exe”. The following two commands show the actor killing the process and using the “type” command to read the contents of a text file “01.txt,” which was also used in the password gathering activity observed on the day of the initial compromise on Jun 2016, ten months earlier:

taskkill /f /im mom64.exe

type c:\windows\temp\01.txt

Nine days later on May 3, 2017 the next commands came from a fifth IP address apparently in Germany. This time the threat actors issued 10 commands to the TwoFace webshell: fewer than nine days before but still more than during the other sessions.

The actor first issues a command to ping the IP address “4.2.2.4”, which is the legitimate DNS resolver operated by Level 3. The actor then checks the “Domain Admins” group to determine the accounts with domain administrator privileges using the following command:

net group "Domain admins" /domain

After this command, the actor runs a variant of the Mimikatz tool to gather locally logged in passwords, this time using a filename of “MicrosoftUpdate.exe” for the executable and “mic.txt” to store the results, as seen in the following command:

c:\windows\temp\MicrosoftUpdate.exe p::d s::l q > c:\windows\temp\mic.txt

These commands show the threat actors rely heavily on the TwoFace webshell to interact with compromised servers, but it also appears that other webshells are used in addition to TwoFace, such as IntrudingDivisor. The commands also show the threat actor’s reliance on the Mimikatz tool to steal passwords from systems, which they will then use to attempt to move laterally amongst other servers by copying over webshells. Lastly, the timestamps of the commands suggest that the threat actor had maintained persistent access that they used intermittently to the compromised network using the TwoFace shell since at least June 2016.

TwoFace Loader Shell

Both components of the TwoFace shell, which we will refer to as the loader and payload components were written in C# and meant to run on a webserver that supports ASP.NET. The author of the initial loader webshell included legitimate and expected content that will be displayed if a visitor accesses the shell in a browser. The inclusion of expected content suggests that the actors wished to use the TwoFace webshell for extended periods while remaining hidden.

The code in the loader webshell includes obfuscated variable names and the embedded payload is encoded and encrypted. To interact with the loader webshell, the threat actor uses HTTP POST requests to the compromised server. As its name suggests, the loader component is mainly responsible for saving and loading the payload component on the same server, allowing the actor to interact with the payload component that has far more functionality than the loader. However, the loader is also capable of the following functionality:

- Save the TwoFace payload to a specified file on the server

- Delete the TwoFace payload saved on the server

- Write data to a specified file on the server

- Delete the entire folder on the server used to store the TwoFace payload

The TwoFace loader parses the HTTP POST requests issued by the actor and references data at specific locations, more specifically at certain indexes within the posted data (C# “Request.Forms”) that the shell will use to determine the functionality the actor wishes to execute. While we did not have logs of HTTP requests for the loader shell, we were able to determine some of the indexes that the webshell will specifically access within the data. Table 2 shows the known indexes within the HTTP POST data that TwoFace references.

| Request.Forms Index | Description |

| 0 | If set to a specific value (for example, "931201"), it creates a set of "pre" html tags with a string of numbers for reasons unknown. |

| 5 | Data to write to a file on the server |

| 8 | String name for the TwoFace webshell filename |

| 9 | Contains base64 data provided by the actor to specify the command to run, as well as the decryption key in the event the actor wishes to load the webshell |

Table 2 Indexes within Request.Forms that the TwoFace loader relies on

As you can see in the descriptions in Table 2, none of these locations contain the command that the actor wishes to execute. Instead, the actor must provide data in index 9 that was constructed to not only contain the command the actor wants to execute, but also contains the key to decrypt the TwoFace payload component that is embedded within the loader. The data in index 9 will contain data at specific offsets, seen in Table 3 that the loader component will use to determine the command and the location of command specific data within the posted data (C# “Request.Forms”).

| Offset | Value | Description |

| 0 | Varied | The entirety of the data is used as a key to decrypt the TwoFace payload component |

| 25 | 8 | Specifies the argument in the HTTP POST request that contains the string of the filename for the TwoFace webshell file |

| 26 | 1000 | Minimum length required to write data to a specified file |

| 44 | 31 | Contains the number of arguments needed to perform a file deletion operation? |

| 45 | 5 | Specifies the argument within the POST request that contains the data to write to a file on the server |

| 57 | 36 | Contains the number of arguments within the POST request to run a command to write data to a file on the server |

| 61 | 13 | Contains the number of arguments within the POST request to run a command to install the TwoFace payload webshell |

| 63 | 14 | Contains the number of arguments needed to perform a folder deletion operation? |

Table 3 Offets of actor provided data used by the TwoFace loader

Saving the TwoFace Payload

The main purpose of the loader shell is to install a secondary webshell on demand. The secondary webshell, which we call the payload, is embedded within the loader in encrypted form and contains additional functionality that we will discuss in further detail. When the threat actor wants to interact with the remote server, they provide data that the loader will use to modify a decryption key embedded within the loader that will be in turn used to decrypt the embedded TwoFace payload. The decryption algorithm (below) is very simple, as it relies on basic arithmetic operations, specifically addition and subtraction to decrypt the embedded payload.

|

1 2 3 4 |

for(int i = 0; i < key.Length; i++) key[i] += actorProvidedData[i % actorProvidedData.Length]; for(int j=0;j<ciphertext.Length;j++) ciphertext[j] -= key[j % key.Length]; |

The pseudocode above provides the logic used by the TwoFace loader to decrypt the ciphertext of the payload, which is

- Iterate through the key, modifying each byte by adding a value from the actor’s provided data

- Iterate through TwoFace payload ciphertext and subtracting each byte using a value from the modified key

We were able to determine the data that the threat actor would have to provide to successfully decrypt the embedded TwoFace payload, which is as follows:

\x15@^\xbbs\xfa\xae\x876\x03`\xffs\x89\xb9 \x9a\xcb\x02\xec\x8e\xc3\x92\x7f\xd6b\xa8\x1ag\xb8\xff\x82\x08\xd0ALB\xd8\x0c)\x91\x82\xc4\x85\xb2\xa7\xe6\xea\x8e\x92\xf9u\x96\xc1\xef\xfd\xe9.!\x047\xc8#y

As you can surmise from the above characters, this does not appear to be a human generated string. We believe this is a machine generated string used for this input data, which gives a bit of insight into the actors behind this webshell, as they would have to use a tool to interact with to automate the use of these webshells, or at a minimum they would need to keep track of these machine generated user input strings to be able to interact with their webshells manually.

TwoFace Payload Shell

The TwoFace payload shell requires a password that is sent within HTTP POST data or within the HTTP Cookie, specifically with a field with a name “pwd”. The “pwd” field is used for authentication as a password, which the payload will generate the SHA1 hash and compare it with a hash that is hardcoded within the payload. We extracted the SHA1 hashes used for authentication from the known TwoFace shells, as seen in Table 4 and were able to find the associated password string for three of them. One of the passwords, “RamdanAlKarim12” contains a phrase that means “Ramadan the generous” in Arabic (رمضان الكريم). Another known password is “FreeMe!”, while the last known password contains what may be an acronym of a middle eastern energy organization followed by “pass”. It is possible that the actor chose this acronym based on the targeted organization, but we cannot confirm this.

| Sample SHA256 | Embedded SHA1 Password |

| 8f0419493d… | a2c9afd6adac242827adb00d76c20c491b2d2247 |

| 0a77e28e6d… | 6a0e681586988388d4a0690b6fb686715d92d069 |

| 54c8bfa0be… | 5e1c37bf3bd8a7567d46db63ed9b0aeed53e57fe |

| 818ac924fd… | 37ada887553cf48715cc19131b8e661ac43718e9 |

| fd47825d75… | 9789b5c0c13fb58c423bce5577873d413d9494be |

| 79c9a2a2b5… | c56bc0d331a825fdea01c5437877d5e9e1cda2c4 |

| e33096ab3… | 9f4e10484f4ceac34878d4f621a1ad8e580fd02a |

| c116f078a0… | 57dd9721f9837ebd24dea55a90a2a9e3e6ad6f1e |

Table 4 Authentication hashes and matching password strings used for TwoFace webshells

Much like the authentication password, a threat actor can issue commands to the TwoFace payload using either data sent within the HTTP Cookie or HTTP POST data itself. If using an HTTP Cookie to issue commands, the payload will split the cookie data using the delimiter “#=#” and will treat the first value as the command and the second value the data to pass to the command. We enumerated the command handler, which can be seen in Table 5 that accepts a variety of commands to interact with the compromised server.

| Command | Arg Field | Description |

| Execute application or command | pro | Executable to run command line commands |

| cmd | Runs a supplied command using “cmd.exe” or another executable supplied by the user via the “pro” field within the HTTP POST data. | |

| Upload a file to the server | upl | Field name within the HTTP POST files that contains the file contents to save to the server |

| sav | Path to save file to | |

| vir | Boolean to save a file to a virtual path rather than a physical path | |

| nen | Specified name of file to upload, otherwise the script uses the filename of the uploaded file from the HTTP POST request | |

| Upload data to a file in the %TEMP% folder | upb | Base64 encoded data that is decoded and saved to a file |

| upd | Filename in the %TEMP% folder to save ‘upb’ data to | |

| Delete a file in %TEMP% folder | del | Filename in the %TEMP% folder to delete |

| Download a file from the server | don | Path to file to download from the server |

| View or set MAC timestamps of a file | hid | 1 = View the ‘tfil’ MAC times

2 = Set ‘tfil’ file MAC times to match the file specified in the ‘ttar’ field 3 = Set ‘tfil’ file MAC times to times specified in the ‘ttim’ field |

| tfil | Filename to get or set MAC times | |

| ttar | Filename to get MAC times, most likely a legitimate filename used to make uploaded files look as if they are legitimate | |

| ttim | Specific timestamp to set file MAC times to |

Table 5 Commands available within the TwoFace payload webshell

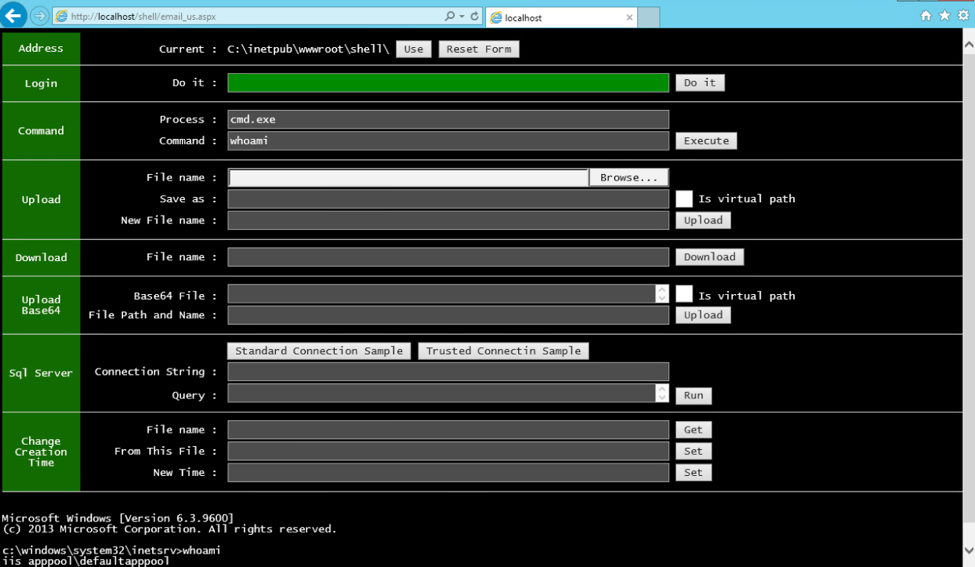

While the commands within Table 5 are available within TwoFace, the threat actor does not have to manually issue these requests within HTTP POST data, as the actor can interact with the webshell using a web form within the browser. We set up an IIS server to test the TwoFace webshell, which displays the user-interface seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1 TwoFace payload webshell before authentication

At first, the text box in the row labeled “Login” has a red background, which means the user has not successfully provided the password required to issue commands to the webshell. After entering the correct password in the login box, the box changes from a red to green background, as seen in Figure 2. The actor can now interact with the compromised server using the webshell, which runs the commands described in Table 5. In most cases, the output or results of commands are displayed immediately below the webshell. For instance, in Figure 2 we issued the “whoami” command that used the Windows command-prompt to display the name of the current user account below the webshell.

Figure 2 Issuing a command on TwoFace webshell after successfully authenticating

TwoFace++ Loader

We discovered another version of the TwoFace loader shell that was structurally similar to the TwoFace loader shell discussed in this blog, as this version of TwoFace also contains an embedded payload shell in encrypted form. To use the embedded payload shell, the actor must provide a password that the loader shell will not only use for authentication, but also as a key to decrypt the payload.

The actor will provide the password in the HTTP POST data, specifically as a base64 encoded string within a field labeled “p”. The TwoFace++ loader will decode this password and concatenate a static salt value and compute the SHA1 hash of this string. The loader then base64 encodes the SHA1 hash and compares it with a hardcoded base64 encoded string of a SHA1 hash needed for successful authentication. We know of the SHA1 hashes 19be2493b7cc2d43e8bf245b6faf2c747be6bae5 and 26749c6b5308bb668eb954f4120607c2a9d620be used for authentication, however, we have been unable to determine the passwords that would result in these hashes.

The TwoFace++ loader will use the actor provided password as a decryption key to decrypt the embedded payload shell. The loader will use the first 24 bytes of the actor’s password as a key, which it will use the 3DES symmetric cipher to decrypt the payload shell. The embedded payload is 8624 bytes, which we believe is another webshell based on the previous version of the TwoFace loader, however, we have been unable to decrypt the payload to confirm.

IntrudingDivisor Webshell

Our analysis of the commands issued to the TwoFace webshell resulted in the discovery of another webshell that we call IntrudingDivisor. Like TwoFace, the IntrudingDivisor webshell requires the threat actor to authenticate before issuing commands. To authenticate, the actor must provide two pieces of information, first an integer that is divisible by 5473 and a string whose MD5 hash is “9A26A0E7B88940DAA84FC4D5E6C61AD0”. Upon successful authentication, the webshell has a command handler that uses integers within the request to determine the command to execute, specifically integers divisible by the following:

| Divisor | Command |

| 6571 | Write provided data to a specified file |

| 9273 | Execute a command or change the modified and access times of a file |

| 3471 | Read a specified file |

Table 6 Commands available within the IntrudingDivisor webshell

The webshell logs the IP, user-agent, and timestamp of all requests to a file named "KB45253-ENU.exe”, but we have seen another IntrudingDivisor sample logging requests to “KB76862-ENU.exe” as well. We believe the threat actor will use the IntrudingDivisor in a similar manner to TwoFace, specifically to gain access to additional servers during lateral movement and to gather user credentials.

Conclusion

The TwoFace webshell has an effective two-layer approach that makes it difficult to detect. Coupled with the multiple layers and inclusion of legitimate website content that displays correctly in the browser, the threat actors are able to enjoy long periods of persistent access to a network without detection as evidenced by their demonstrated ability to access and manipulate a compromised system for nearly a year. Based on the commands issued to TwoFace, the threat actors used this webshell to deliver variants of the Mimikatz tool to gather the passwords of logged on accounts. The actor also used TwoFace to move laterally by copying webshells to other remote systems on the network.

TwoFace Loader SHA256

ed684062f43d34834c4a87fdb68f4536568caf16c34a0ea451e6f25cf1532d51

f4da5cb72246434decb8cf676758da410f6ddc20196dfd484f513aa3b6bc4ac5

9a361019f6fbd4a246b96545868dcb7908c611934c41166b9aa93519504ac813

d0ffd613b1b285b15e2d6c038b0bd4951eb40eb802617cf6eb4f56cda4b023e3

TwoFace++ Loader SHA256

bca01f14fb3cb4cfbe7f240156feebc55abac73a6c96b9f75da2f9df580101ef

8d178b9730e09e35c071526bfb91ce72f876797ebc4e81f0bc05e7bb8ad1734e

TwoFace Payload SHA256

8f0419493da5ba201429503e53c9ccb8f8170ab73141bdc6ae6b9771512ad84b

0a77e28e6d0d7bd057167ca8a63da867397f1619a38d5c713027ebb22b784d4f

54c8bfa0be1d1419bf0770d49e937b284b52df212df19551576f73653a7d061f

818ac924fd8f7bc1b6062a8ef456226a47c4c59d2f9e38eda89fff463253942f

fd47825d75e3da3e43dc84f425178d6e834a900d6b2fd850ee1083dbb1e5b113

79c9a2a2b596f8270b32f30f3e03882b00b87102e65de00a325b64d30051da4e

e33096ab328949af19c290809819034d196445b8ed0406206e7418ec96f66b68

c116f078a0b9ea25c5fdb2e72914c3446c46f22d9f2b37c582600162ed711b69

IntrudingDivisor Shell SHA256

e342d6bf07de1257e82f4ea19e9f08c9e11a43d9ad576cd799782f6e968914b8

49f43f2caaea89bd3bb137f4228e543783ef265abbdc84e3743d93a7d30b0a7e

Mimikatz SHA256

f17272d146f4d46dda5dc2791836bfa783bdc09ca062f33447e4f3a26f26f4e0

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42