Malicious actors have utilized Command & Control (C2) communication channels over the Domain Name Service (DNS) and, in some cases, have even used the protocol to exfiltrate data. This is beyond what a C2 “heartbeat” connection would communicate. Malicious actors have also infiltrated malicious data/payloads to the victim system over DNS and, for some years now, Unit 42 research has described different types of abuse discovered.

DNS is a critical and foundational protocol of the internet – often described as the “phonebook of the internet” – mapping domain names to IP addresses, and much more, as described in the core RFCs for the protocol. DNS’ ubiquity (and frequent lack of scrutiny) can enable very elegant and subtle methods for communicating, and sharing data, beyond the protocol’s original intentions.

On top of the examples of DNS use mentioned already, a number of tools exist that can enable, amongst other things, their attackers to create covert channels over DNS for the purposes of hiding communication or bypassing policies put in place by network administrators. A popular use case is to bypass hotel, café etc Wi-Fi connection registration by using the often-open and available DNS. Most notably these tools are freely available online in places like GitHub and can be easy to use. More information about these tools can be found in the Appendix section at the end of this report.

In this report we introduce the types, methods, and usage of DNS-based data infiltration and exfiltration and provide some pointers towards defense mechanisms.

DNS

DNS uses Port 53 which is nearly always open on systems, firewalls, and clients to transmit DNS queries. Rather than the more familiar Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) these queries use User Datagram Protocol (UDP) because of its low-latency, bandwidth and resource usage compared TCP-equivalent queries. UDP has no error or flow-control capabilities, nor does it have any integrity checking to ensure the data arrived intact.

How is internet use (browsing, apps, chat etc) so reliable then? If the UDP DNS query fails (it’s a best-effort protocol after all) in the first instance, most systems will retry a number of times and only after multiple failures, potentially switch to TCP before trying again; TCP is also used if the DNS query exceeds the limitations of the UDP datagram size – typically 512 bytes for DNS but can depend on system settings.

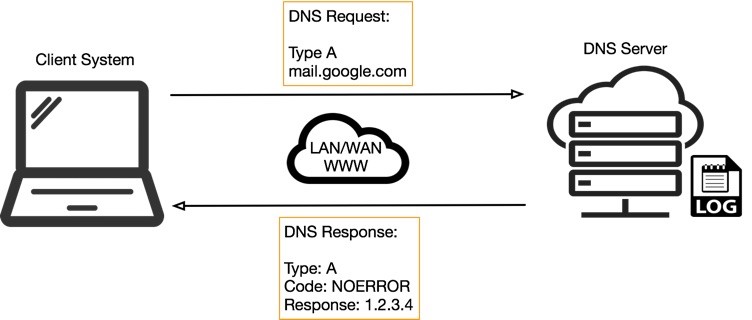

Figure 1 below illustrates the basic process of how DNS operates: the client sends a query string (for example, mail.google[.]com in this case) with a certain type – typically A for a host address. I’ve skipped the part whereby intermediate DNS systems may have to establish where ‘.com’ exists, before finding out where ‘google[.]com’ can be found, and so on.

Figure 1. Simplified DNS operation

Once a name is resolved to an IP caching also helps: the resolved name-to-IP is typically cached on the local system (and possibly on intermediate DNS servers) for a period of time. Subsequent queries for the same name from the same client then don’t leave the local system until said cache expires. Of course, once the IP address of the remote service is known, applications can use that information to enable other TCP-based protocols, such as HTTP, to do their actual work, for example ensuring internet cat GIFs can be reliably shared with your colleagues.

So, all in all, a few dozen extra UDP DNS queries from an organization’s network would be fairly inconspicuous and could allow for a malicious payload to beacon out to an adversary; commands could also be received to the requesting application for processing with little difficulty.

If you want to go deep on how DNS works – all the way from you typing keys to spell the domain name you want to browse – then please read this article.

Data Trail

Just as when you browse the internet, whether pivoting from a search engine result or directly accessing a website URL, your DNS queries also leave a trace. How much of a trace depends on the systems and processes involved along the way, from the query leaving the operating system, to receiving the resultant IP address.

Focusing on the server-side only and, using some basic examples, it’s possible for DNS servers – especially those with extended or debug logging enabled – to gather a whole host (no pun intended) of information about the request, and client requesting it.

This article provides some idea of the type of information that could be gleaned from DNS server logs; an adversary operating such a server gets the remote IP sending the request – though this could be the last hop or DNS server’s IP, not the exact requesting client’s IP – as well as the query string itself, and whatever the response was from the server.

DNS Tunneling

Now that we have a common understand of DNS, how it operates in a network, and the server-side tracing capabilities, let’s dig a little deeper into the tunneling capabilities. In this section we will describe how command and control (C2) beacons can operate over DNS, and how data exfiltration and infiltration is possible.

C2

A C2 channel often serves two purposes for the adversary. Firstly, it can act as a beacon or heartbeat indicating that their remote payload is still operating – still has a heartbeat – as it’s beaconing-out (communicating) to their server.

You could consider the basic DNS operation, as shown in Figure 1 above, as an example of a heartbeat. If the malicious implant on the client system repeatedly sends a query to the actor’s server through the DNS infrastructure, the actor could tell from the logs that an implant is running. What becomes difficult is distinguishing between multiple victims that are infected with the implant.

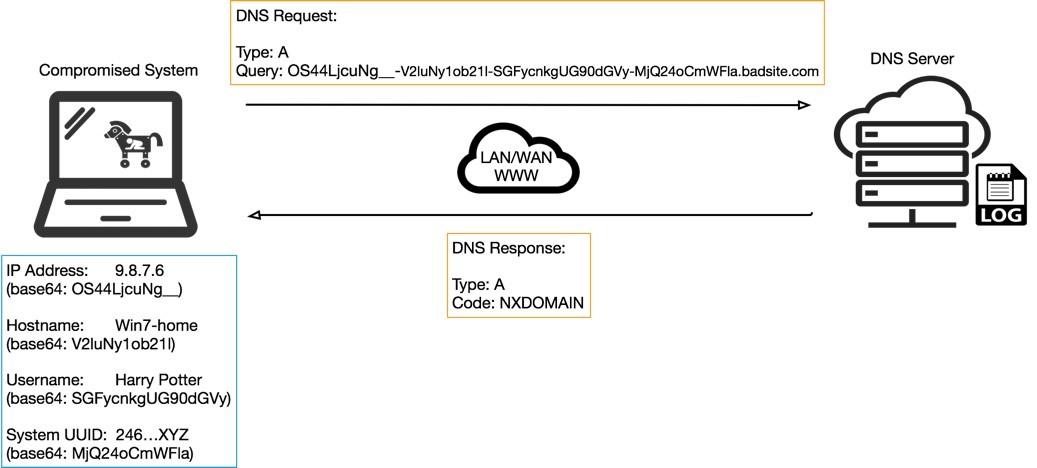

Consider another example described by Figure 2 below, where the client system is compromised with malware that’s constructing strange-looking query strings to send over DNS. Queries like these still act as a heartbeat indicating to the adversary their payload is still active, however they also provide some basic meta-data about the victim and, importantly, ways to uniquely identify one victim from another.

Figure 2. Example C2 DNS query operation

Usernames and hostnames may not always be unique, and some IPs could be duplicated across multiple networks using Network Address Translation (NAT), however systems do have Universal Unique Identifiers (UUIDs) or other properties, that when combined could create a unique identifier for a given host or victim.

Some of the meta-data from the compromised host could be sent as plaintext but might appear more suspicious at first glance to anyone seeing such strings in a DNS query. In many cases the data will contain characters not supported by DNS, in which case encoding will be required. In Figure 2 you can see the base64 encoded equivalent for the meta-data, which is constructed using a ‘-‘ delimited notation for simple parsing and decoding on the server-side, as shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3. Server-side DNS logs tracking C2 communication

Figure 3 shows an example of what a raw DNS log from a DNS server application may look like, with line entries for the malware’s query and the DNS server’s response, NXDOMAIN (or non-existent domain), in this case.

In some ways, a log like this, or perhaps a small database containing the decoded records from them, could be compared to the more snazzy-looking botnet control panels that allow the botnet herder to control their zombie victim systems.

Exfiltration

So, what else could be sent up in DNS queries? Well, anything in theory, so long as it’s encoded correctly and doesn’t abuse the UDP size limits. A way for getting around the latter constraint could be to send multiple A record messages and have them stitched together somehow on the server-side. Complications would arise however in dropped or missing datagrams.

Unlike TCP that ensures retransmission of failed packets, UDP has no such mechanism. An algorithm would be required to understand how many messages will be sent, and check the correct number arrives, but more complicated than that, somehow ask the client to retransmit certain segments of the data again until 100% arrives. Depending on the amount of data to transmit – every PDF on the system, for example – may take an age, and look hugely suspicious to network administrators.

Infiltration

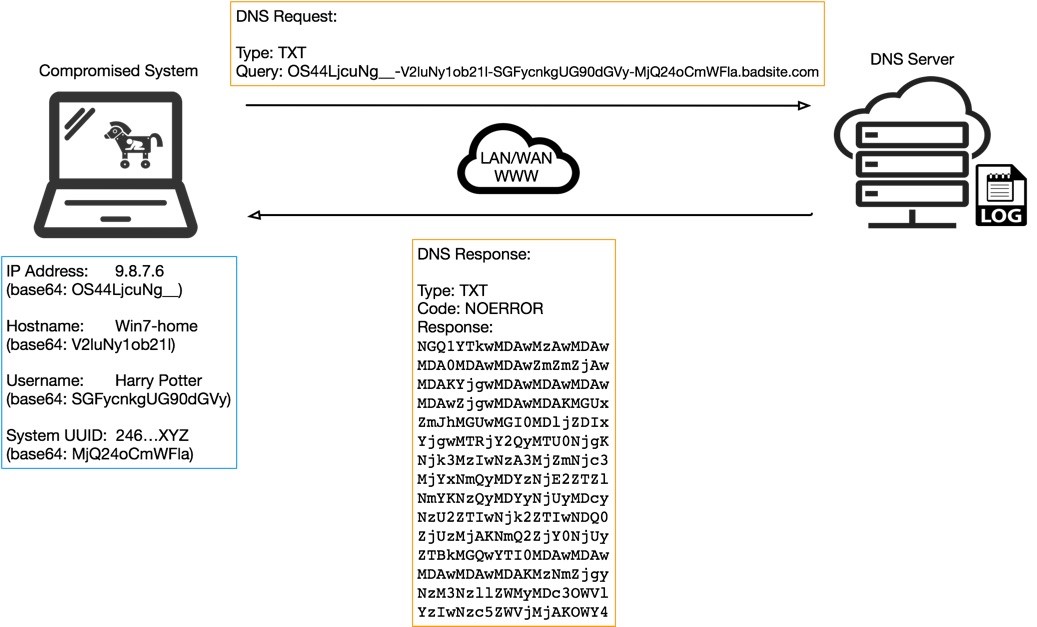

In contrast, infiltration of data whether it be code, commands, or a binary file to drop to disk and execute could be much easier, especially using the DNS type of TXT (as opposed to host record type A). TXT types were designed to provide descriptive text, such as service details, contact names, phone numbers, etc in response to TXT DNS queries for domain names.

Guess what looks likes text? Base64-encoded non-text data! Figure 4 below shows the identical query being sent to the malicious site as in Figure 2, however, the type is now TXT on both the request and response, and the response data contains the first 300 or so characters of an encoded binary executable file that could be executed by the client malware. Again, using the logs, the adversary would be able to know which client asked for the payload, and that the payload was sent (who knows if it actually arrived…).

Figure 4. Example C2 DNS query with TXT type response

But how does the malicious implant know to change the type to TXT or when to request whatever lies inside the “text” data? It could be built-in to the payload to query at a certain point in its execution or after a certain amount of time but in reality, it’s going to be actor-driven using the second purpose of a C2 channel – control.

In my earlier examples of C2 DNS communication the response from the DNS server was NXDOMAIN. This message obviously reaches the client system (and the malware) and could be used a message or instruction for the payload but it’s limiting without parameters and detail. Enter NOERROR.

NOERROR, as the term suggests means everything worked fine – your request was processed and an answer awaits you. With a NOERROR comes a response that can be processed. Usually this is the IPv4 (for A type requests) or IPv6 (for AAAA type requests) or it could be TXT, as shown in Figure 4 above. Focusing on a simple example – the IPv4 address response – the malware doesn’t need an actual IP to communicate with, unlike your browser that asked “where is google[.]com at?”. The malware is already in communication to its destination using the C2 over DNS.

What the malware can use the IP response for is any one of 4,294,967,296 possible commands or instructions. Again, keeping this very simple still, it’s possible that a particular value in the 4th octet of the IP, say, 100, would indicate to the malware to send a TXT DNS query to the actor’s domain to collect and execute a payload. Value 10 in the first octet could mean to uninstall and wipe traces of the malicious payload from the operating system and event logs. Literally, the options are endless, as are the levels of possible sophistication.

Given the adversary has control over the DNS server, and that certain DNS server applications or daemons are highly configurable, it’s possible to send conditional responses back to the malware on the victim systems based on requests sent from them.

For example, if the incoming query contains a certain flag – a character – as the first subdomain to the domain name, it could be read by a program running inside the DNS service on the server and provide a custom response back to the client. This could be used for the malware to work through a set of tasks automatically, and report back accordingly to the actors to receive their next task.

Conclusion

DNS is a very powerful tool used almost everywhere allowing applications and systems to lookup resources and services with which to interact. DNS provides a communication foundation enabling higher-level and more powerful protocols to function but can mean it’s overlooked from a security point of view, especially when you consider how much malware is delivered via email protocols or downloaded from the web using HTTP.

For these reasons, DNS is the perfect choice for adversaries who seek an always-open, often overlooked and probably underestimated protocol to leverage for communications from and to compromised hosts. Unit 42 has seen multiple instances of malware, and the actors behind them, abusing DNS to succeed in their objectives, as discussed in this report.

Organizations can defend themselves against DNS tunneling in many different ways, whether using Palo Alto Networks’ Security Operating Platform, or Open Source technology. Defense can take many different forms such as, but not limited to, the following:

- Blocking domain-names (or IPs or geolocation regions) based on known reputation or perceived danger;

- Rules around “strange looking” DNS query strings;

- Rules around the length, type, or size of both outbound or inbound DNS queries;

- General hardening of the client operating systems and understanding the name resolution capabilities as well as their specific search order;

- User and/or system behavior analytics that automatically spot anomalies, such as new domains being accessed especially when the method of access and frequency are abnormal.

- Palo Alto Networks recently introduced a new DNS security service focused on blocking access to malicious domain names.

Further information can also be found in the ATT&CK framework documentation on Mitre’s website. Specifically, the following techniques relate to concepts discussed in this report.

| ID | Technique |

| T1048 | Exfiltration Over Alternative Protocol |

| T1320 | Data Hiding |

| T1094 | Custom Command and Control Protocol |

Thanks to Yanhui Jia, Rongbo Shao, Yi Ren, Matt Tennis, Xin Ouyang, John Harrison and Jens Egger for their input on this report.

Appendix: Toolkit List

| Tool Name | Description |

| dns2tcp | dns2tcp was written by Olivier Dembour and Nicolas Collignon. It is written in C and runs on Linux. The client can run on Windows. It supports KEY and TXT request types. [4] |

| tcp-over-dns | tcp-over-dns (TCP-over-DNS) was released in 2008. It has a Java based server and a Java based client. It runs on Windows, Linux and Solaris. It supports LZMA compression and both TCP and UDP traffic tunneling. [4] |

| OzymanDNS | OzymanDNS is written in Perl by Dan Kaminsky in 2004. It is used to setup an SSH tunnel over DNS or for file transfer. Requests are base32 encoded and responses are base64 encoded TXT records. [4] |

| iodine | iodine is a DNS tunneling program first released in 2006 with updates as recently as 2010. It was developed by Bjorn Andersson and Erik Ekman. Iodine is written in C and it runs on Linux, Mac OS X, Windows and others. Iodine has been ported to Android. It uses a TUN or TAP interface on the endpoint. [4] |

| SplitBrain | SplitBrain is a variant of OzymanDNS. |

| DNScat-P / dnscat2 | DNScat (DNScat-P) was originally released in 2004 and the most recent version was released in 2005. It was written by Tadeusz Pietraszek. DNScat is presented as a “Swiss-Army knife” tool with many uses involving bi-directional communication through DNS. DNScat is Java based and runs on Unix like systems. DNScat supports A record and CNAME record requests (Pietraszek, 2004). Since there are two utilities named DNScat, this one will be referred to as DNScat-P in this paper to distinguish it from the other one. [4] |

| DNScapy | DNScapy was developed by Pierre Bienaime. It uses Scapy for packet generation. DNScapy supports SSH tunneling over DNS including a Socks proxy. It can be configured to use CNAME or TXT records or both randomly. [4] |

| TUNS | TUNS, an IP over DNS tunnel, was developed by Lucas Nussbaum and written in Ruby. It does not use any experimental or seldom used record types. It uses only CNAME records. It adjusts the MTU used to 140 characters to match the data in a DNS request. TUNS may be harder to detect, but it comes at a performance cost. |

| PSUDP | PSUDP was developed by Kenton Born. It injects data into existing DNS requests by modifying the IP/UDP lengths. It requires all hosts participating in the covert network to send their DNS requests to a Broker service which can hold messages for a specific host until a DNS request comes from that host. The message can then be sent in the response. |

| Your Freedom | HTTPS/UDP/FTP/DNS/ECHO VPN & tunneling solution for Windows, Mac OSX, Linux and Android. Bypass proxies and access the Internet anonymously |

| Hexify | A tool is developed by Infoblox to do the penetrating test for DNS tunneling. |

Appendix: Malware List

| Malware Name | Description |

| DNS_TXT_Pwnage | A backdoor capable of receiving commands and PowerShell scripts from DNS TXT queries. |

| DNSMessenger | DNSMessenger is Remote Access Trojan (RAT) that opens a backdoor so that hackers can control the compromised machine remotely |

| OilRig - BONDUPDATER | Trojan against a Middle Eastern government can use A records and TXT records within its DNS tunneling protocol for its C2 communications |

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42