Introduction

Every now and then, a new domain name system (DNS) vulnerability that puts billions of devices around the world at risk is discovered. DNS vulnerabilities are usually critical. Just imagine that you browse to your bank account website, but instead of returning the IP address of your bank website, your DNS resolver gives you the address of an attacker’s website. That website looks exactly the same as the bank’s website. Not only that, but even if you take a look at the URL bar, you won’t see anything wrong because your browser actually thinks this is the website of your bank. This is an example of DNS cache poisoning.

In this article, I will explain what DNS is as well as review the history of DNS cache poisoning vulnerabilities, from past vulnerabilities to more advanced ones that were discovered in recent years.

The vulnerabilities I chose to cover are the bread and butter of almost all DNS cache poisoning attacks that took place in the last 20 years.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected from the attacks outlined in this blog in a variety of ways: Next-Generation Firewalls with a DNS Security Service subscription and Prisma Cloud.

What is a DNS?

The domain name system is a hierarchical and decentralized naming system for computers, services or other resources connected to the internet (or a private network). It associates various information with domain names assigned to each of the participating entities.

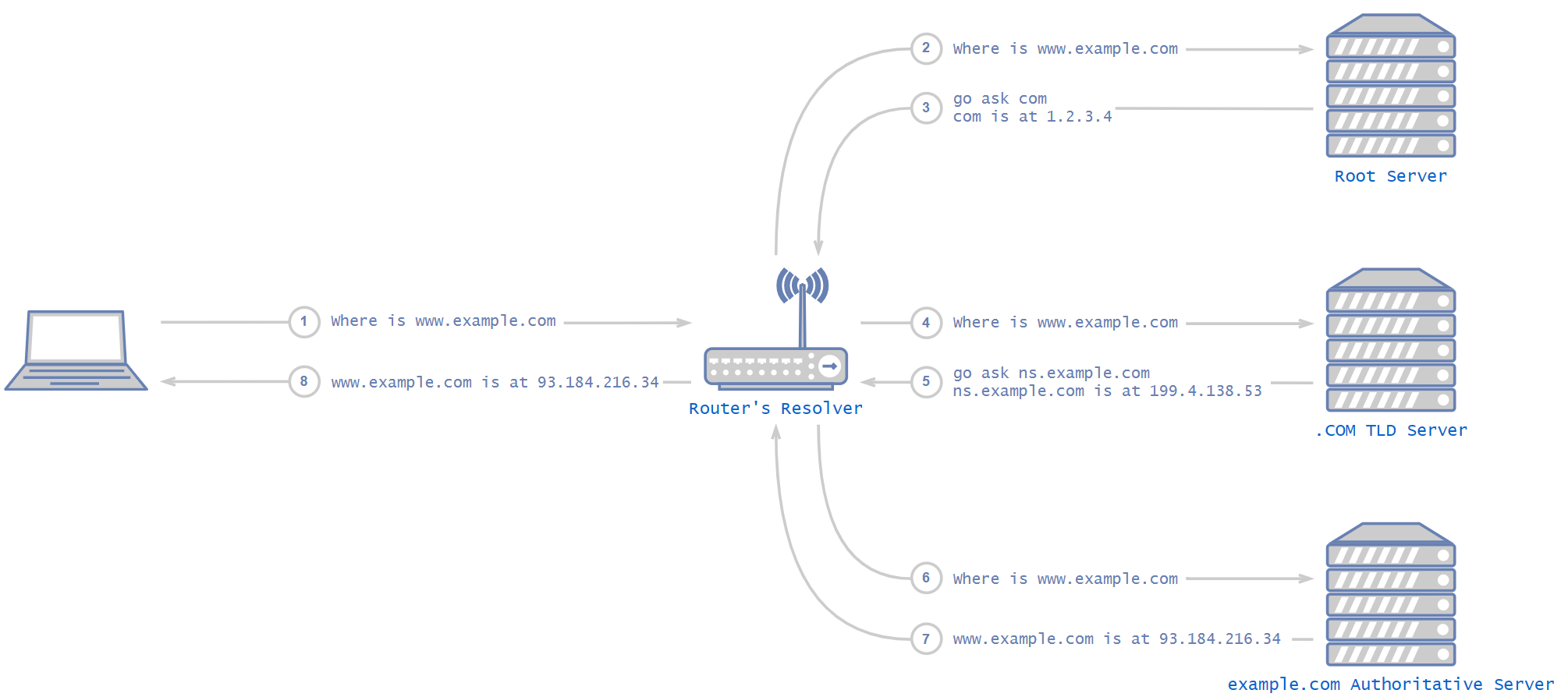

In simple terms, DNS is a protocol that is mostly used to convert a name into an IP address. When one browses http://www.example.com, the www.example.com domain name is being translated to the actual IP address, for example, 93.184.216.34.

What is a DNS Server?

DNS servers, usually referred to as name servers, are devices or programs that provide DNS resolution. DNS clients, which are built into most desktop and mobile operating systems, interact with DNS servers in order to translate names to IP addresses.

It is important to remember that eventually there are only two types of servers: an authoritative name server and a recursive name server. The authoritative name server is the name server that is in charge of the domain – the last in the chain. Everything that isn’t an authoritative name server is a recursive one. For example, routers’ DNS servers, ISPs’ DNS servers and Kubernetes clusters’ DNS servers are all recursive name servers. All those recursive servers behave the same way. Eventually, after some recursions, they contact the authoritative name server of the desired domain (there are servers that perform functions of both authoritative and recursive name servers, which we will not discuss in this blog).

How Does It Work?

A DNS resolver is the lowest node in the DNS hierarchy – the one in your Kubernetes cluster, for example. The basic idea of how DNS works is that when a DNS resolver is being asked about a domain it doesn’t know, it starts by asking the DNS root server. Root servers are the highest nodes in the hierarchy and their addresses are hardcoded in the resolver. The root server answers with a list of addresses for the relevant top-level domain' (TLD) DNS servers, which are in charge of the relevant DNS zone (.com, .net, .etc). The TLD server answers with the address of the next, hierarchically lower server, and so on, until an authoritative server is reached.

DNS in the Cloud

Cloud computing skyrocketed in popularity in recent years. The way cloud products implement DNS might not be intuitive in some cases. Virtual machines in the cloud are pretty straightforward. The DNS resolver is determined by the virtual machine’s operating system. If using Windows, then Windows has its built-in DNS resolver. If using Linux, then it is distribution-dependent.

But what about other cloud products like Kubernetes? Unlike simple virtual machines, Kubernetes uses a custom virtual machine for its nodes, one that doesn’t come with a built-in DNS resolver.

Each Kubernetes cluster also contains a special containerized DNS resolver. All the applications in the cluster forward their DNS requests to this containerized DNS resolver, which handles them.

In the past, up to version 1.10 of Kubernetes, it used to be kube-dns, a package of applications for handling, caching and forwarding DNS requests. The core application in kube-dns was dnsmasq. dnsmasq is a lightweight, easy-to-configure DNS forwarder, designed to provide DNS services to a small-scale network. Since then, Kubernetes moved to CoreDNS, which is an open source DNS server written in Go. CoreDNS is a fast and flexible DNS server.

Cache

Cache is a hardware or software component that stores data, so that future requests for that data can be served faster. It is a very important feature in DNS servers. DNS servers use cache to store previously translated names.

For example, if client C tried to access www.example.com and the name server resolved www.example.com to 93.184.216.34, it will save that IP address of www.example.com for an arbitrary amount of time so the next DNS client that contacts it to try to resolve this name will be answered immediately from the cache.

What Is DNS Cache Poisoning?

DNS cache poisoning is a type of attack on DNS servers that eventually ends with the server saving an attacker’s controlled IP address for a non-attacker’s controlled domain.

For example, an attacker manages to trick a DNS server into saving the www.example.com IP address as 13.37.13.37, which is an evil IP address that the attacker controls, instead of the actual real IP address.

From this point onwards, and until the cached IP address is timed out, every DNS client that tries to resolve www.example.com will be “redirected” to the attacker’s website.

Past DNS Vulnerabilities

No Mitigations

There were many DNS attacks that were discovered in the last 20 years. I will describe DNS cache poisoning, also known as DNS spoofing, the most widely known DNS attack.

So how does DNS cache poisoning work?

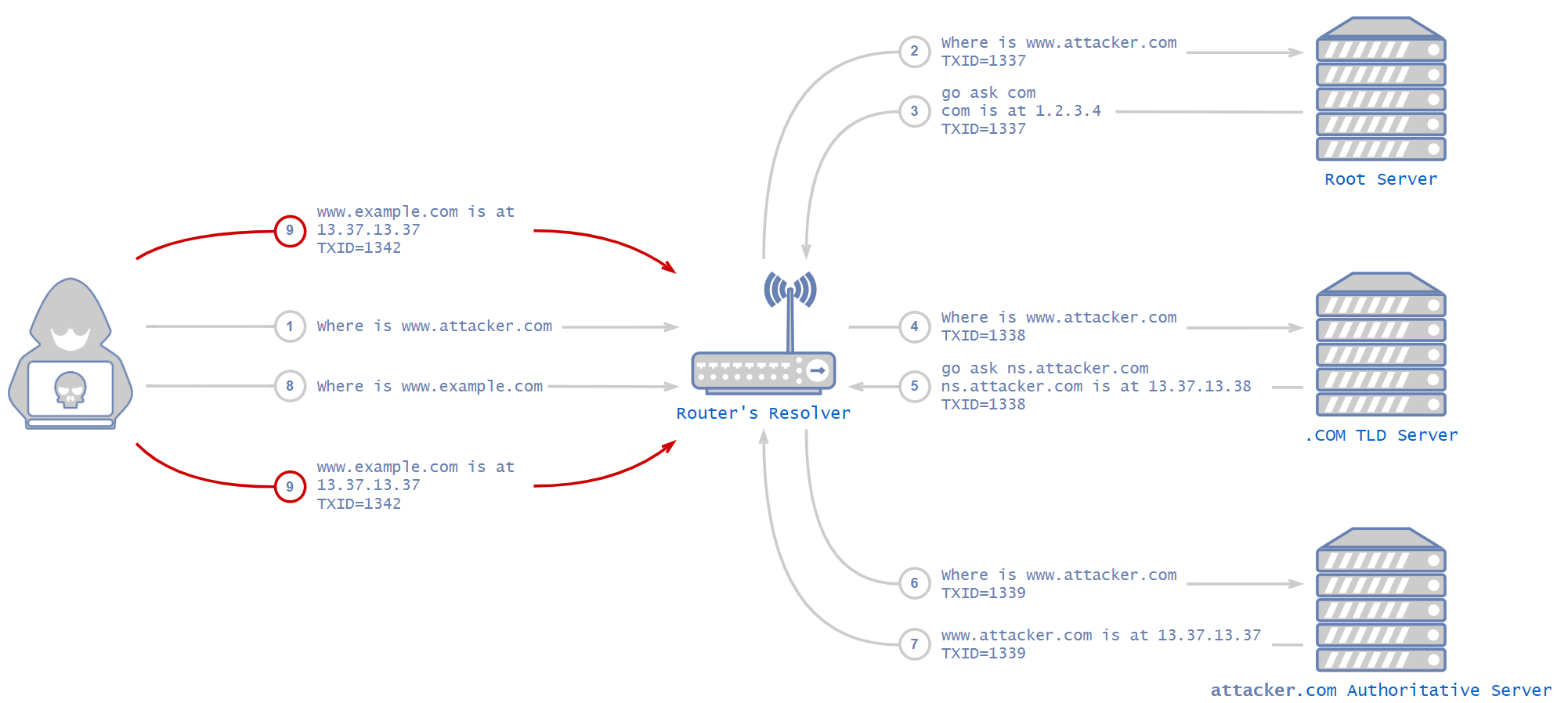

As explained above, it takes some time for the resolver to resolve the IP address of a domain. It usually needs to contact multiple servers before getting to the authoritative one. Attackers can abuse this period of time to send fake answers to the resolver.

This attack is possible in the following scenarios, all of which result in an attacker being able to send packets to the resolver:

- A resolver that leaves its listening port open to the internet.

- An attacker that manages to get control of an endpoint in the internal network.

- A client in the internal network that browses to an attacker controlled website.

For example, let’s assume that an attacker penetrated one of the endpoints in the internal network and is now looking to poison the local resolver’s cache. It is important to note that this attack can be implemented, in the exact same way, on more critical resolvers such as an ISP’s resolver.

The client visits www.example.com and the domain is missing from the resolver cache, so it initiates the process described above to resolve the address of the domain. In the meantime, the attacker sends an answer packet to the resolver with a fake IP address, faking the DNS server answer. This is the basic idea of the attack, but there are a few mitigations. These include transaction ID and source port randomization.

DNS uses something called transaction ID (TXID) to match each response to the correct request. An attacker has to supply a response with the correct transaction ID or the DNS server will just drop the packets. When this mechanism was invented, many years ago, it wasn’t intended to be a security feature, but simply a way to match responses to requests. Before DNS vulnerabilities were discovered, DNS used an ascending index as the transaction ID. It was simple for an attacker to guess that number.

An attacker would have had to buy a domain and configure their own controlled DNS server. Next, the attacker would ask the resolver in the local network about their own domain. The local resolver would forward the request up the hierarchical DNS ladder until it reached a DNS server that knew the attacker’s controlled DNS server. At this point, the original DNS request (the one that the attacker issued from the internal network) would get to the attacker’s controlled DNS server, thus revealing the transaction ID to the attacker.

Using the transaction ID the attacker discovered earlier, they would have a good idea of the transaction ID needed for the fake response to be accepted. In such a case, an attacker could send multiple fake responses with multiple transaction IDs to make sure one of them was the correct one. Then, all there is left for an attacker to do is issue a DNS request for a domain that is not in the local DNS resolver’s cache and immediately send fake responses using the transaction ID for that domain.

The local resolver would get the response with the correct transaction ID, drop the others and cache the address. From now on, and for an arbitrary amount of time, any local client that would have visited that domain would be directed to the attacker’s website.

New Mitigations

The obvious mitigation, which was implemented, was to randomize the transaction ID for each request (instead of using an ascending counter). This mitigation made the attack much harder to execute. How much harder? Well, MAX_SIZE_OF_QUERY_ID harder. Transaction ID is 16 bits, so that mitigation made the attack 65,536 times harder than before. Not bad – but not bulletproof either.

Round Two, Fight!

Those mitigations held off attackers for quite some time, but eventually the internet caught up. While a 16-bits randomization key is quite large, it isn’t nearly large enough. Let's do the math.

For the following calculation, we need to put down some data:

- Size of a typical DNS response: 100 bytes = 800 bits

- Bandwidth of the attacker: 1 Megabits per second = 1,000,000 bits

- Time it takes for a legitimate response to get back to the resolver: two seconds

(A side note about the two seconds: Nowadays, with modern internet connection, it obviously takes less than two seconds to fulfill a DNS request, even for domains that aren’t cached. But as I picked a latency for the sake of example, I also chose an internet speed from the past: 1 Megabits per second.)

There are 65,536 possible transaction IDs, and we have a window of two seconds to send a response with the correct one for a successful attack. In order to calculate our success rate per attack, we need to figure out how many response packets an attacker can dispatch before the actual legitimate response arrives at the resolver. This is easy to calculate: the bandwidth divided by the size of the packet multiplied by the time.

With 1 Mbit/s bandwidth, an attacker can send up to 1,000,000/800 = 1,250 response packets in a second, meaning 2,500 in the two-second window the attacker has. The amount of tries needed to achieve a likely attack, meaning at least 50% success rate with a 1 Mbit/s bandwidth, is about 18 tries.

(You can view the complete calculation here: 1,000,000 is the amount of bits we can send in a second with our 1 Mbits\s connection. We divide that by 800, which is the size of a DNS response that yields the amount of responses we can send in a second. We multiply that by 2 because of the 2-second window. We then divide that by 2 to the power of 16, which is the size of the transaction ID field. That is the success rate of a single attack. In order to achieve a successful attack we need that in x attempts, one of the attempts will be successful. Our x attempts are called an “experiment”, and the set of all possible outcomes of that experiment is called a sample space (Ω). The chance of hitting anything in the sample space is obviously 100% (this is the outer 1 in the equation). In order to get the chance of a likely attack, we need to take the entire sample space and subtract from that anything that is not “succeeding in at least a single attack” which is another way to say failing in all x attempts. Failing in a single attempt is “everything (1) minus succeeding in a single attempt” which is exactly 1 minus success rate. We then tell Wolfram Alpha that we are looking for an x that will result in this equation in a number bigger than 0.5, which is 50%.)

In other words, with only 18 tries, an attacker with 1 Mbit/s bandwidth could achieve a success rate that is bigger than 50% with this attack after the mitigations. This is how easy it was to craft this devastating attack back in the day.

More Mitigations

At first, it might seem odd that such a weak mitigation was chosen, but it is important to remember that it was simply impossible to completely reinvent the DNS protocol. It would have broken the internet. Just think of all the devices out there that have a built-in resolver. They would have completely stopped working. But something more had to be done. As demonstrated, transaction ID mitigation was weak.

So the same mitigation was used, this time with the source port. Each DNS request from a DNS client, resolver or name server comes out from a source port. That port wasn’t randomized prior to this mitigation.

The source port is a 16 bits number, same as the transaction ID, and it was there for functionality only. For example, a resolver might try to use port 10650, and if that was in use from a previous request, it would try to use 10651 and so on. Of course, not all 16 bits were available, as there are constant ports for other uses.

The source port, combined with the transaction ID, are used together as a key for DNS communication – a 32 bits key. Remember that, as it will be important in the attacks I will further discuss. Those extra 16 bits reduced the probability of a successful attack drastically.

Before, with a 1 Mbit/s bandwidth, we had a success rate of 3.8% (You can view the relevant calculation in Wolfram Alpha). With the source port mitigation, with the same data as before, the probability of successful attack is 0.00005821%. The number of attempts are needed to achieve the same likely successful attack as before is 1,190,820. That makes the success of the attack not reliable enough – and indeed, the source port randomization put an end to most DNS cache poisoning attacks.

More Advanced Vulnerabilities

So far, we have focused on poisoning the cache of a single DNS record, “www.example.com is at 93.184.216.34”, also known as an A record. We were poisoning the record at the victim’s own DNS server, like a router or a Kubernetes cluster. In this approach, we work hard on a difficult attack to poison a single domain. We could do better.

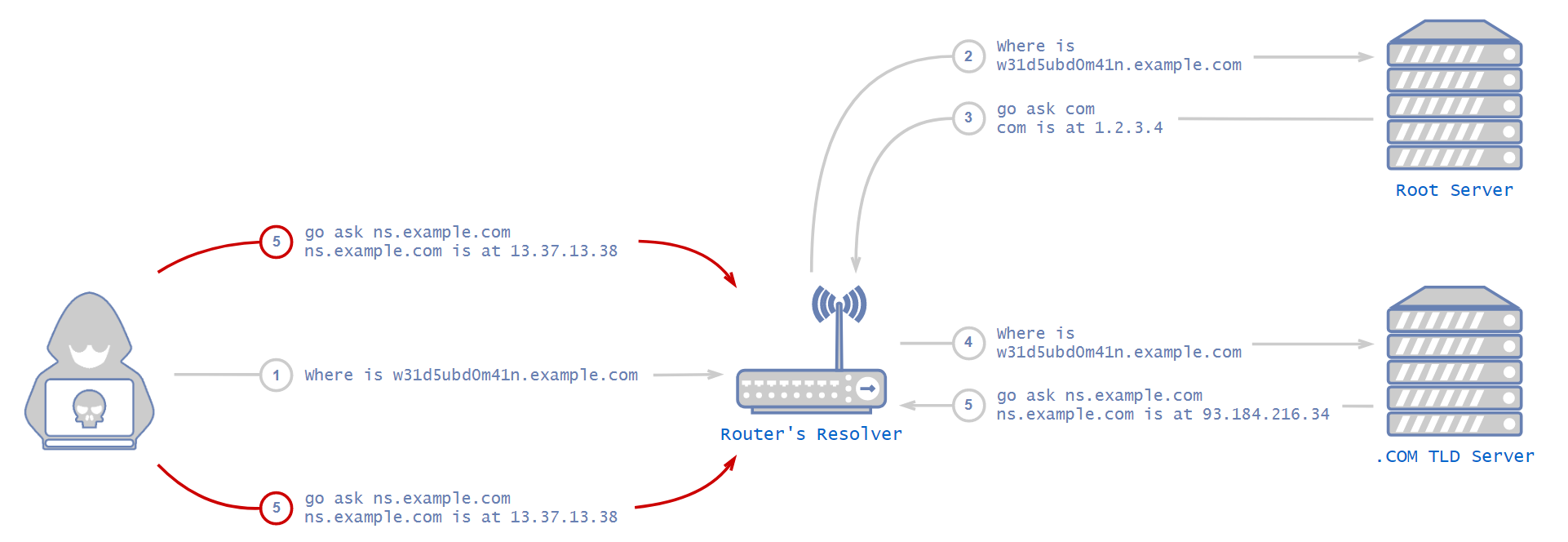

In 2008, security researcher Dan Kaminsky discovered a better approach that's drastically more effective than what we have discussed so far in this blog. This vulnerability caused quite a furor in the security community. The general execution method is quite similar to what we discussed so far, meaning we still need to guess the transaction ID and the source port. The probability of succeeding in that is pretty much the same, but in Kaminsky’s method, we could have poisoned a lot more than a single record if we had succeeded.

NS Record

As the name suggests, a name server (NS) record is a DNS record that indicates which DNS server is authoritative for a domain, meaning which server contains the actual IP address of a domain. In our example earlier, the NS record for example.com would be a server that holds the addresses of www.example.com, email.example.com and any ?.example.com.

The attacker’s goal here is to poison the victim’s resolver in such a way that when the victim tries to access www.example.com, email.example.com or any ?.example.com, the resolver will forward the request to the attacker’s name server instead of the example.com name server.

This way, the attacker controls every access to every single subdomain of example.com instead of just www as before.

But How?

Surprisingly, the attack is very similar to the previous attacks that we’ve described in this blog, but instead of poisoning the cache of the resolver with an A record, an attacker will attempt to poison the cache with an NS record.

An attacker would first configure a name server for the domain they want to poison. There is nothing stopping anybody from configuring their own name server to be authoritative for any domain. However, it would ordinarily be pointless as no other server would point to it.

The attacker would then proceed to issue a DNS request for the subdomain of the zone they want to poison. It would have to be a domain that isn’t cached, so they would know for sure the resolver will forward the request to a root server. Not only that, but the NS record of that domain in our example, the authoritative name server of example.com, shouldn’t be cached either. If it were cached, the resolver would simply forward the request to that authoritative name server directly, without even forwarding the request to the root server.

After the attacker makes the victim’s resolver forward their request to the root server, the root server will usually answer with an NS record, which is roughly equivalent to saying, “I don't know the answer, but you can ask this server over there. Here is its IP address.”

This is the tricky part. To succeed in the attack, the attacker now needs to outperform the root server and deliver the poisonous response before the root server’s response is sent. This is achieved by sending large amounts of responses with an NS record of the desired domain. Don’t forget the attacker needs to guess the transaction ID (and possibly the source port, too).

Each NS answer comes with a “glue” record, which is the actual IP address of the name server. If it was any other way, the requesting server wouldn't know where to find the name server. The resolver receives this glue record, caches it and contacts the name server that the glue points to in order to get the address of the requested domain.

If the attack succeeds, from now on, each request to the resolver for any domain that is uncached under the poisoned domain zone (example.com in www.example.com) would arrive at the attacker’s name server.

Applications

With this advanced attack, an attacker can poison a large amount of domains at the same time. Theoretically, an attacker could even poison the entire .com zone.

While poisoning a zone as big as .com would be challenging, there have been cases where an attacker actually managed to poison an entire cache. Some examples:

- On Jan. 26, 2015, a hacker group managed to redirect visitors to the Malaysia Airlines website to another site displaying malicious content.

- On Nov. 7, 2011, hackers managed to poison an entire internet service provider’s cache, redirecting users to the installation of malware before redirecting them back to the site they requested.

- On Dec. 18, 2009, a DNS hijacking attack left Twitter temporarily affected for about an hour.

Hundreds of such attacks take place every year.

Mitigations

No actual new mitigations took place, as this attack was already nearly impossible to execute with the transaction ID and port randomization mitigations that were already used. But if an attacker managed to overcome those mitigations, using this attack instead of the “regular” single A record attack would be much more severe.

In the same way as before, using transaction ID and port randomization together to create a key large enough to be too hard for an attacker to guess mitigates the attack.

Recent Vulnerabilities

Even if the DNS protocol is considered secure, developers could fail to implement it securely.

For example, there is a common misconception that randomization functions should be unpredictable, so they can be used to generate cryptographic keys. However, those functions are not meant to be used for cryptography or security. Unfortunately, misuse of randomization functions frequently happen in the case of DNS implementations.

This happened with the function that was used to randomize the transaction ID in CoreDNS, just two years ago. The developers chose to use math.rand, which is a non-cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generator in Golang. This was a big problem. If an attacker could predict the transaction ID, they would absolutely be able to poison CoreDNS’s cache as described earlier in this blog. It means that every application that used CoreDNS as its DNS resolver would have been vulnerable to malicious DNS records. In other words, because CoreDNS is mainly used for Kubernetes, every single application in every single node in the entire cluster would have been vulnerable to this attack.

Another example is a new technique that was discovered just a few weeks ago, which uses the Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) to pinpoint which ports are closed on a server, thus revealing which ports are actually open. This, used in a DNS attack, can drastically reduce the number of ports an attacker needs to guess, reducing the effectiveness of the port randomization mitigation explained earlier.

And of course, there are also typical non cache-related vulnerabilities like buffer overflows. dnsmasq is a common DNS resolver used in many Linux distributions and routers, and was even used in early versions of Kubernetes. In recent years, dnsmasq was found vulnerable to numerous memory flaws that could lead to denial of service (DoS), remote code execution (RCE) and more.

Conclusion

The DNS attacks described in this blog could be devastating if successful. Thanks to modern mitigations, an attacker is unlikely to pull off a DNS poisoning attack, unless combined with any other vulnerability in resolver applications. Unfortunately, such vulnerabilities are frequently found to this day.

Over the years, researchers discovered techniques to overcome some of the mitigations we discussed in this blog, for instance, user datagram protocol (UDP) fragmentation.

Despite that, with secured browsing and certificates usage nowadays, even if an attacker manages to poison a DNS server for a domain, it is most likely that the browser’s victim won’t load the page because the certificates won’t match. But the technique can still be used for enormous DoS attacks by poisoning an ISP’s DNS resolver and forwarding requests to a non-existent IP address.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected from the attacks outlined in this blog in a variety of ways. Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewalls can block DNS attacks by detecting suspicious DNS queries and anomalous DNS responses. Attacks related to exhaustion or high quantities of traffic are handled with DoS or zone protection profiles that are built into the firewall. These protections are in addition to coverage of DNS threats and indicators through DNS Security Service.

Furthermore, Prisma Cloud can protect your clusters by alerting about outdated and vulnerable components, as well as misconfigured applications in your cloud. Most of the attacks described in this blog require a breach in the internal network of the cluster to be able to send malicious packets to the DNS server from the inside. Such breaches almost always happen by exploiting outdated and misconfigured applications.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42