Executive Summary

On March 2, the world was introduced to four critical zero-day vulnerabilities impacting multiple versions of Microsoft Exchange Server (CVE-2021-26855, CVE-2021-26857, CVE-2021-26858 and CVE-2021-27065). Alongside revealing these vulnerabilities, Microsoft published security updates and technical guidance that stressed the importance of patching immediately, while concurrently noting active and ongoing exploitation by an Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) they call HAFNIUM. Since the initial attacks, Unit 42 and a number of other threat intelligence teams have seen multiple threat groups now exploiting these zero-day vulnerabilities in the wild. Both the vulnerabilities themselves and the access that can be achieved by exploiting them are significant. It is therefore unsurprising that multiple attackers sought and continue to seek to compromise vulnerable systems before they are patched by network administrators. This has been going on at an unprecedented scale – as of March 8, based on telemetry collected from the Palo Alto Networks Expanse platform, we estimated there remained over 125,000 unpatched Exchange Servers in the world.

Based on the reconstructed timeline, it’s now clear that there were at least 58 days between the first known exploitation of this vulnerability on Jan. 3 and when Microsoft released the patch on March 2. Applying the patch is a necessary first step, but insufficient given the amount of time the exploit was in the wild. The act of patching will not remediate any access that attackers may have already gained to vulnerable systems. Organizations can look to our remediation guide for steps they can take to ensure they have properly secured their Exchange Servers.

As we enter the second week since the vulnerabilities became public, initial estimates place the number of compromised organizations in the tens of thousands, thereby dwarfing the impact of the recent SolarStorm supply chain attack in terms of victims and estimated remediation costs globally. Given the importance of this event, we are publishing a timeline of the attack based on our extensive research into the information currently available to us and our direct experience defending against these attacks. As the situation continues to unfold, we urge others to also share what they uncover so that we as a cybersecurity community get a complete picture as quickly as possible.

Microsoft Exchange Server Attack Timeline Summary

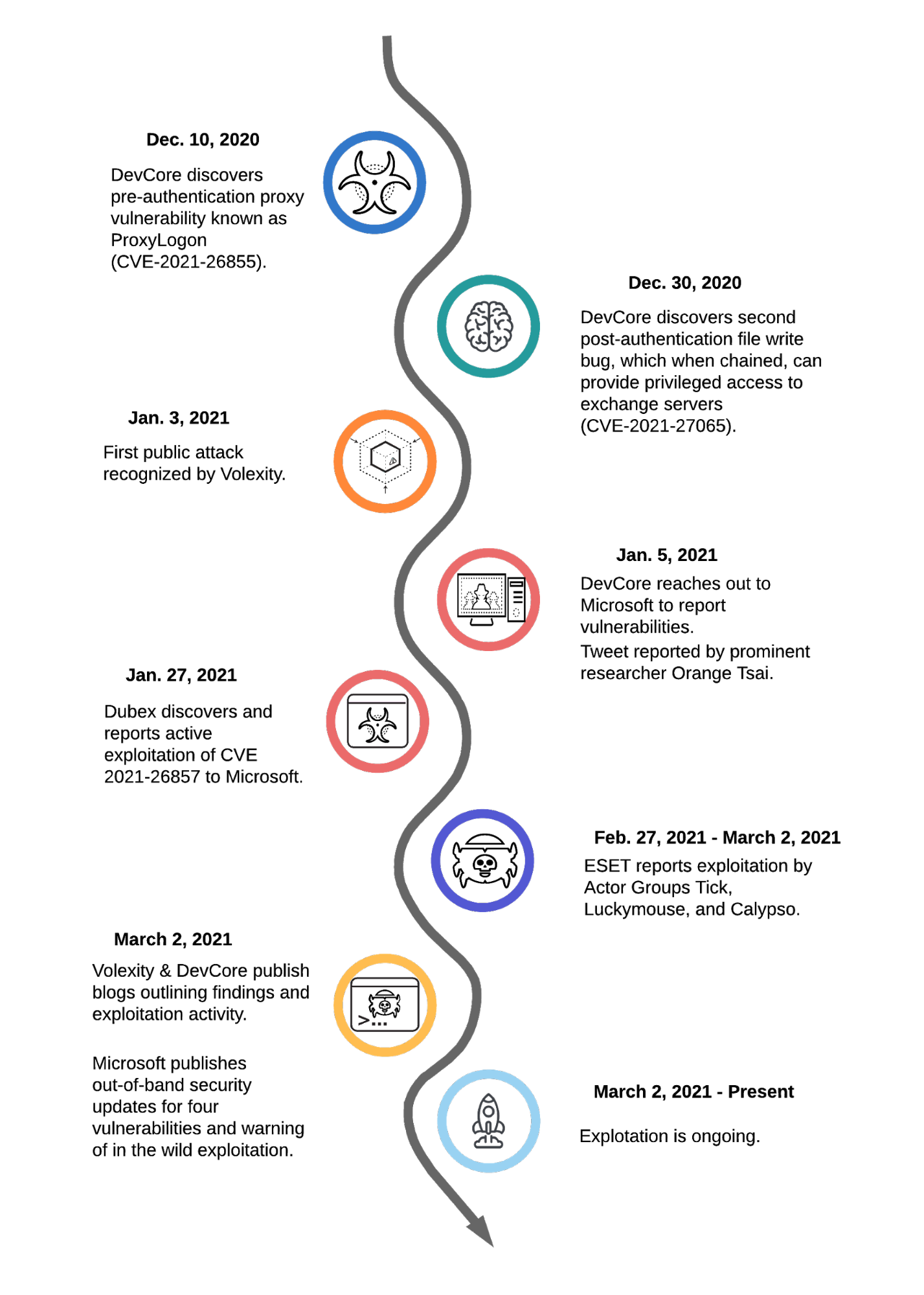

This story begins over six months ago when DevCore, a Taiwan-based security consulting firm, first initiated a project to explore the security of Microsoft Exchange Server products. In the two-month window between October and December 2020, DevCore researchers made considerable progress that ultimately led to the discovery of a pre-authentication proxy vulnerability on Dec. 10, 2020. This vulnerability was given the name ProxyLogon by DevCore and is now known publicly as CVE-2021-26855.

Following this initial discovery, on Dec. 27, 2020, DevCore researchers demonstrated that this vulnerability could be leveraged to perform authentication bypass, thereby granting its users administrator-level permissions on vulnerable Exchange Servers. Shortly after this discovery, on Dec. 30, 2020, DevCore also discovered a second post-authentication file write bug that could be chained together with the first vulnerability to gain privileged access to Exchange Servers and write files of an attacker’s choosing to any directory. This second vulnerability is now known publicly as CVE-2021-27065.

Given the time of year and the existence of a long New Year’s holiday weekend, DevCore reached out and notified Microsoft of the vulnerabilities on the following Tuesday (Jan. 5, 2021). At the time, the researcher credited with the discovery of the vulnerabilities tweeted publicly.

At that point, attacks were already appearing in the wild. Volexity, a US-based security firm, reported attacks involving the ProxyLogon vulnerability as early as Jan. 3. On Feb. 2, the firm also reported to Microsoft information about attacks that occurred on Jan. 6.

Concurrently, it is now believed that Dubex, a Denmark-based security firm, first noted active exploitation of the Microsoft Exchange UMWorkerProcess on Jan. 18, 2021. This vulnerability is now known as CVE-2021-26857. It was used by an adversary to install webshells on vulnerable servers consistent with the attacks noted by Volexity. It has been reported that Dubex notified Microsoft of its findings on Jan. 27, less than 10 days after initial discovery.

With two cybersecurity vendors providing evidence of active exploitation, DevCore followed up with Microsoft on Feb. 18, 2021. During the exchange, DevCore provided a draft advisory notice and requested details concerning the patch release timeline. At the time, Microsoft shared that they planned to release the patches on March 9.

On Feb. 27, 2021 Microsoft notified DevCore that they were almost ready to release the security patches. That same day, the cybersecurity community observed an uptick in unusual webshell activity, and over the following two days, evidence suggests multiple threat groups began active exploitation activities. ESET reported three separate groups (Tick, LuckyMouse and Calypso) and our own analysis of webshells deployed in this window has identified six unique passwords and clusters of activity that further support the claim of multiple threat groups. It is also worth noting that one of the passwords observed on Feb. 28, 2021 was the name “orange,” which may serve as a reference to the researcher who originally discovered the vulnerability.

On March 2, 2021, a week earlier than initially planned, Microsoft published security updates for the four vulnerabilities. In doing so, they also warned of active exploitation of these vulnerabilities by a group they named HAFNIUM and further described as a state-sponsored APT operating out of China.

In the days following the publication of the CVEs, the cybersecurity community has witnessed a surge of attacks as malicious actors seek to capitalize on the vulnerabilities before network defenders deploy patches. Over the past week, we have also identified the emergence of several new webshell passwords and clusters of activity that have overlapping victim populations. Thus, we currently assess that several additional threat actors with varying motives have launched efforts to exploit these vulnerabilities as well.

Finally, in terms of the timeline, it is important to consider that while the Microsoft security updates were released on March 2, 2021, applying these updates only protects organizations from continued or future exploitation of these vulnerabilities. The security updates do not provide any protection from previous exploitation that may have resulted in compromise prior to the publication of the updates.

As documented above, there is definitive evidence that these exploits were in active use as far back as early January, thus resulting in at least a two-month window of vulnerability. However, a lack of evidence of exploitation prior to January should not be misinterpreted as a lack of adversary activity.

Conclusion

Ongoing research illustrates that these vulnerabilities are being used by multiple threat groups. While it is not new for highly skilled attackers to leverage new vulnerabilities across varying product ecosystems, the ways in which these attacks are conducted to bypass authentication -- thereby providing unauthorized access to emails and enabling remote code execution (RCE) -- is particularly nefarious.

Unit 42 fully expects attacks leveraging these vulnerabilities to not only continue, but to increase in scope, likely including more varied attacks with different motivations, such as ransomware infection and/or distribution. Due to the fact that active attacks from various threat groups leveraging these vulnerabilities is ongoing, it’s imperative to not only patch affected systems, but also follow the guidance outlined from Unit 42’s previous remediation blog.

Additional Resources

- Threat Assessment: Active Exploitation of Four Zero-Day Vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange Server

- Remediation Steps for the Microsoft Exchange Server Vulnerabilities

- Hunting for the Recent Attacks Targeting Microsoft Exchange

- Analyzing Attacks Against Microsoft Exchange Server with China Chopper Webshells

- Attackers Won’t Stop With Exchange Server. You Need a New Playbook

- HAFNIUM targeting Exchange Servers with 0-day exploits

- Operation Exchange Marauder: Active Exploitation of Multiple Zero-Day Microsoft Exchange Vulnerabilities

- Mass Exploitation of Exchange Server Zero-Day CVEs: What You Need to Know

- Microsoft Exchange Exploitation: How to detection, mitigate and stay calm

- Threat Assessment: DearCry Ransomware

- How Quickly Are We Patching Microsoft Exchange Servers

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42