Executive Summary

This 3-part blog series focuses on a practical approach to static analysis of PowerShell scripts and developing a platform-independent Python script to carry out this task. This is Part 2 of a 3-part blog series and you can read Part 1 here to get caught up.

Over the course of the series, I will talk about the ins and outs of behavioral profiling, cover common obfuscation and methods of hiding data within PowerShell scripts, and how we can go about building a scoring system to assess the risks of scripts. In general, I aim to aide other analysts and defenders in this endeavor with ideas and a functional foundation script to hit the ground running.

Introduction

In the first part of this blog, I touched on some general concepts around static analysis, behaviors in PowerShell, and things I needed to consider as I moved into the design phase, which will be the focus of this second blog.

My overarching goal is to profile behaviors and infer their intent in PowerShell scripts so I’ll begin by looking at the script input first. Next, I’ll cover the general process of normalizing and de-obfuscating common PowerShell obfuscation and code hiding techniques that you’ll see in-the-wild (ITW) and provide examples of how script content is modified during processing to reveal more data. Finally, we’ll take a look at the behaviors I’ve identified as important for scoring and how they play into the overall assessment of risk in scoring.

PowerShell Script Input

Input can come in many flavors but for the sake of simplicity, I’ll limit this discussion to PowerShell scripts and not other files which may contain PowerShell commands or embedded scripts, such as ScriptBlock Logs, VBScript, and JavaScript. Regardless of the type, it all begins the same way with preparing the data for processing throughout the rest of the script.

In this case, it’s fairly straightforward to start. As I’ll be dealing heavily with REGEX and string matching on ASCII based character sets used to define function names and other keywords in PowerShell, I need to remove the NULL bytes from the input data so that character encoding is less of a problem down the line. If you’re not familiar with the default Windows code pages or Unicode, just know that they utilize two bytes to represent a character but, for our use-case, we are only interested in the characters which fall in the ASCII range. In a two-byte code page, which deals with the character encoding, the first byte will be NULL. For example, if we wanted to search for an exact match of the word “HELLO” but there are NULL bytes pre-pending each byte representing a character in the ASCII range, then this can lead to matching issues so we’ll strip them out.

The string “\x00H\x00E\x00L\x00L\x00O” becomes simply “HELLO”. This establishes a uniformity in characters to match against before I move the data further downstream for processing.

Preparing Content for Profiling

To accurately profile the PowerShell behaviors, I need to normalize and de-obfuscate as much of the content as possible so that I have the highest opportunity of identifying behaviors in the content; whether they are in plain sight, hidden under multiple layers of obfuscation, or buried within various encoding algorithms.

To do this, the script creates two sets of data from the original content that will be scanned over continuously; one which contains the original content, sans the NULL bytes described earlier, and an alternate one wherein the script builds up new content that it discovers during processing. Sometimes there is little deviation from the original content and it’s entirely driven based on identifying the obfuscation and content hiding methods that may have been employed.

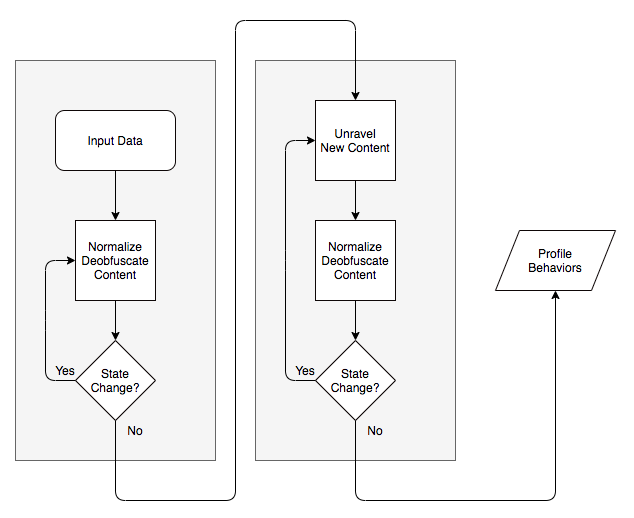

There are two distinct phases here for preparing the content for profiling. One is for cleaning up the content and removing various types of obfuscation and one is for trying to unravel the various ways of burying data within the code that PowerShell supports, such as encryption, compression, and encoding. I’ll step through each of these phases and go over the existing functions that I’ve built into the script to achieve these goals but, before I move on, I need to talk about general obfuscation and how I approached processing.

When you analyze malicious scripts, you’ll frequently find multiple layers and types of obfuscation all contained within a script. What this means is that when the script removes obfuscation from code, it potentially reveals a new code that also needs to be analyzed again to see if it contains more obfuscation or requires more normalization and the process repeats itself. Given this, there needs to be a way to track the state of code and it’s subsequent alteration so that the script can continue processing it until the state fails to change, this workflow is shown in the figure below.

Figure 7. High-level Processing Flow

At a high level, this is relatively straight forward but in practice, there are more practical issues you may run into, such as the order in which the script process different types of obfuscation. These considerations and the order of de-obfuscation or normalization I use in the script were derived over the course of testing and iteration.

As the profiling script is not executing the code, I’m less concerned with unraveling a functional script and more interested in unraveling the raw content; however, when the profiling script does attempt to reverse obfuscation than I try to maintain the integrity of the underlying code where possible. Once the state finally stops changing, the profiling script can move into the behavioral profiling process.

In the current iteration, there are numerous functions for normalizing and unraveling content so I’ll dive into each of them, what their intent is, and discuss how they affect the code.

Normalization / Obfuscation Removal

The identification of obfuscation is typically handled with simple searches or REGEX matches when dealing with non-single character obfuscation. Given the flexibility of PowerShell, you’ll run across dozens of variations for the same commands that can be used so the REGEX patterns I’ve created are designed to capture as many variants as possible, but there is always room for improvement and those included in the script just capture the variants found in my sample set.

To illustrate this idea, consider the following REGEX pattern for capturing variants of the Format String Operator Replacement technique.

|

1 2 |

\((?:\s*)(\"|\')((?:\s*)\{[0-9]{1,3}\}(?:\s*))+\1(?:\s*)-[fF](?: \s*)(\"|\').+?(\"|\')(?:\s*)\)(?![^)]) |

Which can match on things like the following:

|

1 2 3 |

("{1}{0}" -F"exa" ,"mple") ( " {0} " -F "example") ( "{1} {0} " -F 'exa' , "mple" ) |

Basic single-character obfuscation will be removed from the content during processing while the more complex ones will replace the content blocks inline. For each type of obfuscation dealt with, I’ll provide a brief description and a real world example of it in action and what it should transform into.

1. Backticks (`) are used for escaping characters in PowerShell and wrapping lines of code. It’s commonly used in

obfuscation to escape non-special characters and break-up words to prevent matching.

|

1 2 |

if ( ${CoM`P`U`TERn`AME} -eq ${Nu`LL} if ( ${CoMPUTERnAME} -eq ${NuLL} |

2. Carets (^) are escape characters for Windows command line and when you find mixed scripting languages you’ll

frequently see this.

|

1 2 |

echo i^eX(^"^I^e^`X^` echo ieX("Ie`X` |

3. Escaped Quotes (\”) are most commonly seen for substrings that need to be escaped and we’ll want to remove the

escaping so we can accurately profile across that boundary, where a backslash may interfere with pattern matching. In

malicious scripts, these substrings are frequently commands which will be unraveled or passed to new instances of

PowerShell that can be profiled further. Additionally, it can be used to insert empty quotes for additional obfuscation

like below.

|

1 2 |

(g\'\'v KUs).value.toString() (g''v KUs).value.toString() |

4. Empty Quotes (“”) are another trick that can be used to break up variables in PowerShell and otherwise break string

matching, so I remove those when necessary.

|

1 2 |

(g''v KUs).value.toString() (gv KUs).value.toString() |

5. Spaces ( ) can be used to obfuscate in a way that is similar to CaMeL CaSe capitalization; it’s used to confuse the reader

without causing issues with how PowerShell interprets the code.

|

1 2 |

-EX uNrEsTRIcteD -nOP -W HIdDEn -eC-EX uNrEsTRIcteD -nOP -W HIdDEn -eC |

6. Concatenation (+) of strings is another common technique for breaking up strings so the profiling script attempts to

rebuild them. There are many ways of doing concatenation but this one focuses on the use of the addition symbol.

|

1 2 |

New-Object $("Sys"+"tem.Refl"+"ection.Ass"+"embl"+"yName") New-Object $("System.Reflection.AssemblyName") |

- Type Conversion is another technique it looks for as the technique is commonly used for string obfuscation. This is the first of the “brute force” functions in which the profiling script iterate over multiple base values (base8, base16, and base32) to build possible strings, along with trying to identify integers and hexadecimal values stored in lists that can be converted to ASCII.

|

1 2 |

(‘6e,6f,74,65,70,61,64'.SPLiT(‘,’) |fOREAch {( [cHar]([COnVERt]::tOINt16(([STRINg]$_ ) ,16 ))) })-jOIn '') Notepad |

- Splitting, as seen above, goes hand in hand with conversion and you’ll frequently see in malicious scripts this obfuscation using a range of characters to split integers or hexadecimal values. In these cases, the script again takes a shotgun approach to strip out contiguous sets of values and try to decipher as much plain text as possible.

|

1 2 |

27R2cQ20i27p27{29hdQa{7dpd~a'.SPLiT('{p}hiRQ~' )| 27 2c 20 27 27 29 d a 7d d a |

Last, there are two more obfuscation types the profiling script tackles that are a bit more complicated in terms of identification and parsing due to PowerShells flexibility in how things can be called.

7. Format String Operator Replacement has seen a sharp rise of adoption rates in

malicious scripts ever since Daniel Bohannon released Invoke-Obfuscation that uses

this token-style replacement heavily. The functions for statically parsing these with

REGEX require that it considers nested layers of operator replacement, so it targets

smaller inner-versions first and slowly unravels it from the inside-out. It’ll substitute

the parsed string with the replacement command until it’s unable to identify anymore

variants in the content.

|

1 2 |

('V'+("{1}{0}" -f 'b',("{1}{0}" -f 'A','aRi'))+'Le:' ('VaRiAbLe:' |

8. For PowerShell’s built-in string replacement function, the script again uses a REGEX

pattern to identify the many variations possible for this command and attempts to

replace strings across the content.

|

1 2 |

OUT-fILe ("C:c4yprogramdatac4yerror.txt").rEpLAce(("c4y"),'\')' OUT-fILe ("C:\programdata\error.txt") |

These sets of de-obfuscation and normalization functions will be run and re-run again as new content is discovered or the state of the existing data changes.

Unraveling Content

Similar to the above functions for de-obfuscation and normalization of content for profiling, the script also scans the content for certain artifacts to determine if there is additional content that may unraveled. In this next section, I’ll step through the various methods it uses to identify and reveal the content statically.

- Reversed content is one of the simpler types it’ll deal with and, in my experience, isn’t actually that common. In this case, it simply looks for reversed strings of common PowerShell methods and then take the entire content, reverses it, and appends it to the end of the alternate content stream.

|

1 2 |

RAHC[+58]RAHC[+501]RAHC[((eCALpEr.)93]RAHC[]GNirtS[,'V3wfe'(eCALpEr.)).rEpLACe('efw3V',[StriNG][CHAR]39 ).rEpLACe(([CHAR]105+[CHAR]85+[CHAR |

- Another common method of hiding content from view is to utilize the Windows Stream objects which are effectively a class used to encode content. In this case, the profiling script identifies if the calls exist within the visible content and then attempts to deflate the stream. By default, Microsoft uses the same compression algorithm as gzip but the script will attempt to brute force it with a couple of different compression settings to expand coverage.

|

1 2 |

New-Object;iex(a IO.StreamReader((a IO.Compression.DeflateStream([IO.MemoryStream][Convert]::FromBase64String('Cy/KLEnV9cgvLlFQz0jNycnXUSjPL8pJUVQHAA=='),[IO.Compression.CompressionMode]::Decompress)),[Text.Encoding]::ASCII)).ReadToEnd() Write-Host 'hello, world!' |

- Next is Base64, which is probably the most basic and universal encoding scheme around. Nothing fancy here but so it just takes every piece of content which matches a REGEX pattern for Base64 over a certain size (currently 30 bytes), decodes it, and append it to the alternate data stream for profiling.

|

1 2 |

RAB5AG4AYQBtAGkAYwBBAHMAcwBlAG0AYgBsAHkA DynamicAssembly |

- Finally, there is some basic decryption of Microsoft SecureStrings which use the default AES in CBC mode when the SecureString is created with a key. The script looks for the calls to decrypt these SecureStrings and then tries to identify the symmetric encryption key, all of the Base64 content, and the required IV to decrypt the content. I’ve yet to see this technique used in-the-wild (ITW) for a small amount of data that I could use for illustrative purposes so I’ve cobbled together a quick example instead.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 |

> $SecureString = ConvertTo-SecureString "EXAMPLE" -AsPlainText -Force > $StandardString = ConvertFrom-SecureString $SecureString > $Key = (68,111,110,116,72,105,114,101,84,111,109,76,97,110,99,97,1 15,116,101,114,70,65,67,84) > $StandardString = ConvertFrom-SecureString $SecureString -Key $Key > $StandardString 76492d1116743f0423413b16050a5345MgB8AFAAZQBHAHoAeABvAG0AVAA 5AGkAQgA1AEEATABsAGoANABnAFgATABSAFEAPQA9AHwAMAA0ADQANQBiAD EANQA2ADIAYgA3AGQAMwBmADIAZgA1ADYAYgA5AGUAZgAwADAAMgAyADYAZ QAzAGMAMQAzAA== |

The string “EXAMPLE” is encrypted by the 24 bytes and a Base64 value is returned. The inner contents of this Base64 blob, which appear to be a non-publicly documented structure, contain the encrypted string and a Base64 encoded IV. The values are pipe (“|”) delimited so I’ve highlighted the IV in RED and the encrypted data in BLUE. These are what the function will target for decryption.

|

1 2 3 |

\xef\xae=\ xd9\xddu\xd7\xae\xf8\xdd\xfd8\xdb~5\xdd\xbdz\xd3\x9d\x1a\xe7~92|<span style="color: #ff0000;"><strong>PeGzxomT9iB5ALlj4gXLRQ==</strong></span>|<span style="color: #0000ff;"><strong>0445b1562b7d3f2f56b 9ef00226e3c13</strong></span> |

This overview covers all of the techniques I’ve found to be commonly used throughout malicious scripts, along with various types of de-obfuscation or normalization needed to reveal further content. While this by no means is intended to coverage of everything, it’s a good base to start from.

Profiling Known Malware Families

Once the profiling script has as much of the content revealed as possible, it then begins the identification phase. The script starts with first trying to look for known malware families and variants of them as this provides a quick way to score files based off of known indicators and establish intent very quickly. These are primarily REGEX patterns or collections of keywords that uniquely identify malicious scripts such as Magic Unicorn, Social Engineer Toolkit (SET), and Veil. The full list of the currently checked families are below and this section can be added to when new popular formats start appearing ITW.

- Magic Unicorn

- ShellCode Injector

- ICMP Shell

- SET

- PowerDump

- BashBunny

- Veil

- PowerWorm

- PowerShell Empire

- Powerfun

- Mimikatz

- Mimikittenz

- PowerSploit

- DynAmite

- Invoke-Obfuscation

- TXT C2

- Remote DLL

- Cobalt Strike

- Vdw0rm

- Emotet

- mateMiner

- DownAndExec

- Buckeye

- APT34

- MuddyWater

- Tennc Webshell

- PoshC2

- Posh-SecMod

- Invoke-TheHash

- Nishang

- Invoke-CradleCrafter

These were all derived through the aforementioned manual analysis or from previous research. Whenever I found that I was seeing repeating scripts, or structures of scripts, it was a good indicator that it was generated from a framework or script and those usually lend themselves to profiling quite well. Again, it’s not full coverage for any of the above but as you identify new variants or new families, you can add them as a way to expand your coverage.

Profiling PowerShell Behaviors

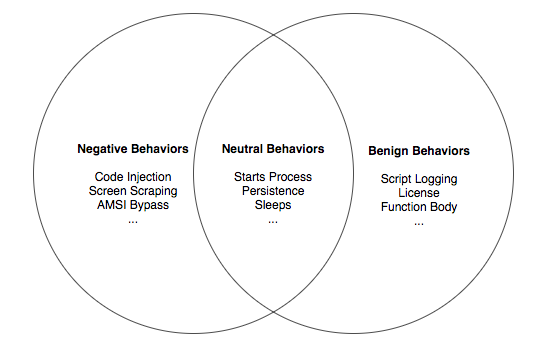

Next we move to the actual profiling of PowerShell behaviors. These are broken into three distinct contextual categories - behaviors generally only seen in malicious scripts, behaviors generally seen in both good and bad scripts (neutral), and finally behaviors generally only seen in benign scripts.

Figure 8. Venn Diagram of behavioral overlap

I’ll list all of them below and their corresponding scores (taken directly from the script) while covering some basics of how they work.

Negative Behaviors

- 'Code Injection': 10.0

- 'Key Logging': 3.0

- 'Screen Scraping': 2.0

- 'AppLocker Bypass': 2.0

- 'AMSI Bypass': 2.0

- 'Clear Logs': 2.0

- 'Coin Miner': 6.0

- 'Embedded File': 4.0

- 'Abnormal Size': 2.0

- 'Ransomware': 10.0

- 'DNS C2': 2.0

- 'Disabled Protections': 4.0

- 'Negative Context': 10.0

- 'Malicious Behavior Combo': 6.0

- 'Known Malware': 10.0

Keep in mind that we’re trying to place a malicious script in the score range of 6+, with the higher the score the more confident we are in the verdict.

For the majority of these, profiling is carried out with simple keyword scanning or combinations of keywords. Let’s take a look at a simple one and how the behavior is defined in the Python code.

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

behaviorCol["Disabled Protections"] = [["REG_DWORD", "DisableAntiSpyware"], ["REG_DWORD", "DisableAntiVirus"], ["REG_DWORD", "DisableScanOnRealtimeEnable"], ["REG_DWORD", "DisableBlockAtFirstSeen"], ] |

For a script to be flagged as having the “Disabled Protections” behavior then, the content must contain one of four variations of “REG_DWORD” and a registry key that I’ve observed in malicious scripts to disable common Windows protection mechanisms such as AntiSpyware and AntiVirus.

Taking a look at another basic example for “Key Logging” shows various combinations of keywords that, when found together, are typically indicative of key logging activity.

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

behaviorCol["Key Logging"] = [ ["GetAsyncKeyState", "Windows.Forms.Keys"], ["LShiftKey", "RShiftKey", "LControlKey", "RControlKey"], ] |

Now, for both “Disabled Protections” and “Key Logging”, the scores are “4.0” and “3.0” respectively, well below the “6.0” threshold for malicious activity. The reason behind this is that sometimes, even though behaviors are predominantly only seen in malicious scripts, they are also used in benign scripts and so I want additional behaviors to add context and push the score beyond the threshold, as opposed to something like “Ransomware” or “Known Malware” where the profiling script immediately sets it above the “6.0” threshold.

A more complex behavior we can look at is “Code Injection”. This is a technique that follows a specific pattern of calls designed to carve out a segment of memory, move shellcode into the memory segment, and then finally transfer execution to the shellcode in memory. The problem is that at each phase of this, there are numerous methods which facilitate the respective functionality; the profiling script accounts for over 1300 variations alone. Thus, we’ll check each individual keyword at each step and only proceed to the next set of keywords if we find one in the previous set. This allows us to keep analysis time low even though the number of variations significantly rises with each addition. Speed is equally important when profiling these at scale and a lot of the profiling script is designed in ways to decrease run time where possible.

When you look at the above behaviors, you’ll also note one called “Malicious Behavior Combo” towards the end. This one is intended to bump malicious scripts that do not exhibit enough behavioral information to generate a score above the target threshold an extra boost as a contextual modifier. The profiling script will look at all of the behaviors for the PowerShell script as a whole and then use it as its own behavior.

The combinations are checked against the aforementioned ground truth of the scripts being used for a baseline to validate the combination of behaviors do not negatively impact benign scripts. It’s important to carefully monitor these as more data can reveal benign scripts which may match; however, this is a good example of using meta-data to influence scoring.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 |

behaviorCombos = [ ["Downloader", "One Liner", "Variable Extension"], ["Downloader", "Script Execution", "Crypto", "Enumeration"], ["Downloader", "Script Execution", "Persistence", "Enumeration"], ["Downloader", "Script Execution", "Starts Process", "Enumeration"], ["Script Execution", "One Liner", "Variable Extension"], ['Script Execution', 'Starts Process', 'Downloader', 'One Liner'], ['Script Execution', 'Downloader', 'Custom Web Fields'], ["Script Execution", "Hidden Window", "Downloader"], ['Script Execution', 'Crypto', 'Obfuscation'], ["Hidden Window", "Persistence", "Downloader"], ] |

Neutral Behaviors

- 'Downloader': 1.5

- 'Starts Process': 1.5

- 'Script Execution': 1.5

- 'Compression': 1.5

- 'Hidden Window': 0.5

- 'Custom Web Fields': 1.0

- 'Persistence': 1.0

- 'Sleeps': 0.5

- 'Uninstalls Apps': 0.5

- 'Obfuscation': 1.0

- 'Crypto': 2.0

- 'Enumeration': 0.5

- 'Registry': 0.5

- 'Sends Data': 1.0

- 'Byte Usage': 1.0

- 'SysInternals': 1.5

- 'One Liner': 2.0

- 'Variable Extension': 2.0

The neutral behaviors are, as the name suggests, neither good nor bad and follow a similar approach to the ones previously discussed. There are a couple of additional meta-behaviors that I want to highlight which are “Obfuscation”, “One Liner”, and “Variable Extension” as they illustrate more diversion from the keyword approach. Just to recap then, meta-behaviors are observed characteristics that are not a specific functionality or capability, but something that describes a characteristic of the PowerShell script.

- One Liner - This one is self explanatory, a script that solely exists on one line. It’s extremely common for malicious scripts or very simple PowerShell download cradles to be constrained on a singular line, whereas benign scripts typically have more structure and include multiple new-lines.

- Obfuscation - This is a case where the script profiles the content for various attributes like character frequency, volume of symbol usage, and volume of variable declarations. These attributes are counted in various ways and highlight observed characteristics of malicious scripts.

- Character frequency analysis reflects standard deviations of character usage that were observed across malicious and benign script sample sets and, for example, will try to identify if “w” is used more than 500 times in the script, or a colon “:” used more than 100 times. There are 13 individual characters that fall into this category and 3 sets of dual characters (“[“ and “]”) which come into play if the script has less than 50 lines; this is usually indicative of a dense clustering of the characters.

- Symbol usage is a specific type of obfuscation that I kept observed being used for variable declarations, such as below.

|

1 |

${/=\__/==\_/\/==\_} = [AppDomain]::CurrentDomain |

-

- Raw volume of PowerShell and JavaScript unique variable declarations over 40.

3. Variable Extension - Another common obfuscation is taking advantage of

PowerShell’s ability to use wildcards (“*”) in variables. The profiling script will

count various commands for retrieving or setting variables and then count

wildcards surrounded by ASCII characters. If those counts are over a certain

amount than it’ll label the obfuscation type as variable extension. To show how it

works, the following code can be used to retrieve “ExecutionContext” and are

often seen chained together to build out other commands.

|

1 2 |

Get-Item Variable:*xec*t ExecutionContext |

In general, the neutral behaviors are scored much lower so that multiple behaviors being flagged won’t generally be enough on their own to cross the established malicious threshold.

Benign Behaviors

- 'Script Logging': -1.0

- 'License': -2.0

- 'Function Body': -2.0

- 'Positive Context': -3.0

The benign behaviors rarely show up in malicious scripts and subtract from the overall score to help influence the context, subtracting from the totals to improve accuracy. For example, malicious scripts typically do not employ logging, licenses, or function preambles. The keyword here being “typically” as sometimes you will find cases where the attacker downloads a script from a PowerShell offensive framework via Github and don’t bother to clean it up. In these cases, there is almost always significant amounts of non-obfuscated behaviors to make up for any drops in score.

Finally, “Positive Context” are specifically used when benign scripts exhibit so many behaviors it crosses the malicious threshold and I want to try and artificially lower their scores. This is more common when dealing with administrative type scripts found in enterprises that perform a wide sweeping range of administrative functions on an endpoint or bootstrap systems.

Conclusion

In this blog I covered common PowerShell techniques for hiding data that I have observed and shown how these can be cleaned up with normalization and by reversing various types of obfuscation. This is a critical step before furtherer unraveling content that will be used as the base for behavioral profiling.

For the next blog in this series, I’ll take more of an in-depth look at how all of these things work together to profile scripts and talk about some observations I’ve made when it comes to statically analyzing PowerShell scripts.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42