Executive Summary

Focusing on one of the most active subsets of the global threat landscape, Palo Alto Networks Unit 42 tracks Nigerian cyber criminals involved in Business Email Compromise (BEC) activities under the name SilverTerrier. Over the past 90 days (Jan. 30 - Apr. 30), we have observed three SilverTerrier actors/groups launch a series of 10 COVID-19 themed malware campaigns. These campaigns have produced over 170 phishing emails seen across our customer base. While broad in their targeting, these actors have exercised minimal restraint in terms of targeting organizations that are critical to COVID-19 response efforts. Specifically, we find it alarming that several of these campaigns recklessly included targets at government healthcare agencies, local and regional governments, large universities with medical programs/centers, regional utilities, medical publishing firms, and insurance companies across the United States, Australia, Canada, Italy, and the United Kingdom.

According to the recently released annual report from the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) observed a record 23,775 BEC attacks in 2019. Significantly greater than all other categories of cybercrime over the same period, these attacks resulted in an estimated US$1.77 billion in global losses.

With the global impacts of COVID-19, an unprecedented number of corporations are expediating their cloud infrastructure migrations, all while transitioning to a largely remote workforce that is understandably interested in all topics related to the virus. Given this trend, it should come as no surprise that BEC actors are seizing opportunities to exploit the situation through tailored phishing campaigns related to COVID-19.

None of the malicious campaigns mentioned in this blog were successful in infecting their intended targets. Palo Alto Networks security service offerings (URL Filtering, WildFire, and Threat Prevention) detect and classify all samples and associated infrastructure as malicious.

Actor 1

We identified the most pronounced activity as a series of eight campaigns that are either directly related, or within one to two degrees of separation, from a SilverTerrier actor that is well-known across the cybersecurity community. For the purposes of this blog, we will refer to this individual as Actor 1.

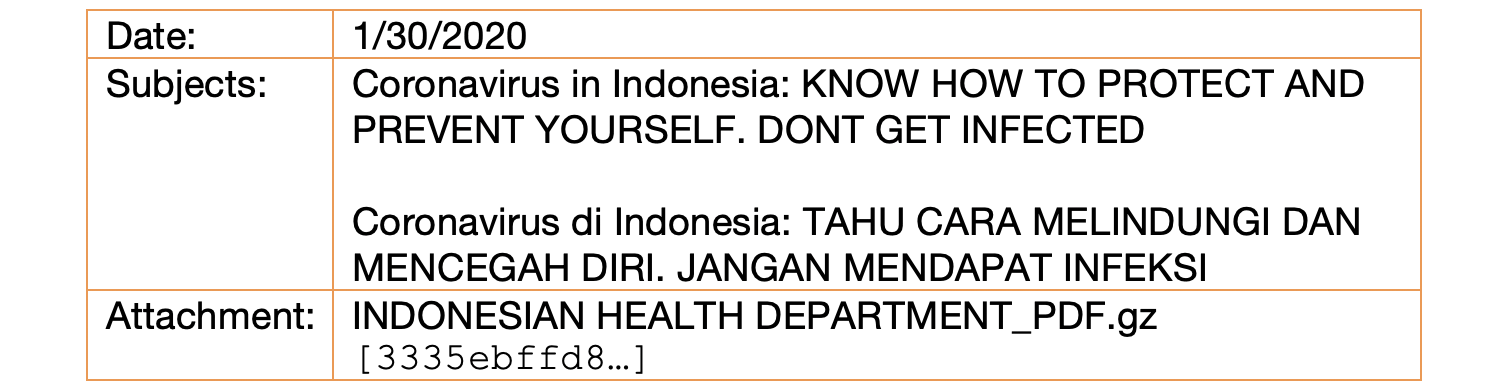

Campaign 1

The first campaign was launched on January 30, 2020 with variations of the email subject sent in both English and Indonesian. Attached to the email was a sample of Lokibot malware disguised as an Indonesian health department document. Upon infecting a victim, the malware was designed to call out to petroindonesia[.]co[.]id.

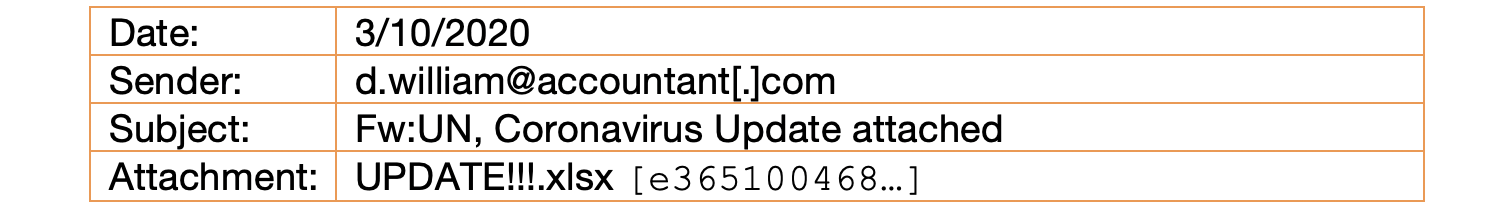

Campaign 2

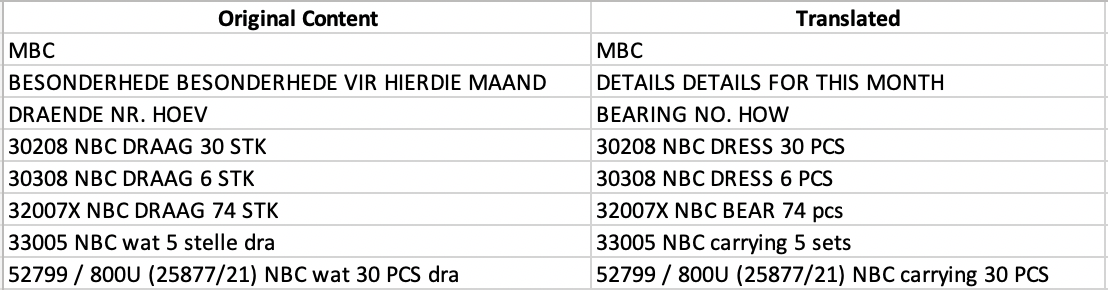

A little more than a month later, we observed a single email sent to a major utility provider in the United States. This message was crafted to appear as if it were an email that had been forwarded from the “UN,” presumed to be the United Nations. Attached to the email was a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet containing text written in the Afrikaans language (Figure 1). Upon opening, the file leverages the CVE 2017-11882 vulnerability to call out and download an executable called “dutchz.exe” from the domain uzoclouds[.]eu and subsequently attempts to connect to via SMTP to mailhostbox[.]com. Although Microsoft has released security updates for this vulnerability, it remains in common use amongst cyber criminals. In attributing this activity, the domain uzoclouds[.]eu stands out as being directly associated with Actor 1, and the Excel file itself was last edited by modexcomm which is a known alias for this actor.

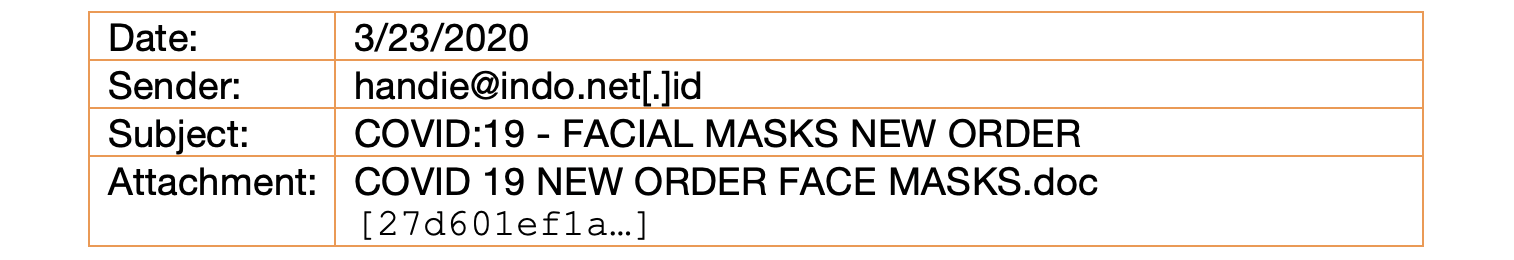

Campaign 3

On March 23, 2020 a third campaign was discovered with several phishing emails sent to an Australian health insurance provider. This time the subject and attachment were scoped to portray an order form for new face masks. Similar to the previous campaign, the attached RTF document leveraged the CVE 2017-11882 vulnerability to call out to both posqit[.]net and bit[.]ly, thus taking advantage of a URL shortening service to obscure one of the connections. Per the research and analysis blog by Cyren, this sample downloads and installs AgentTesla malware.

Campaign 4

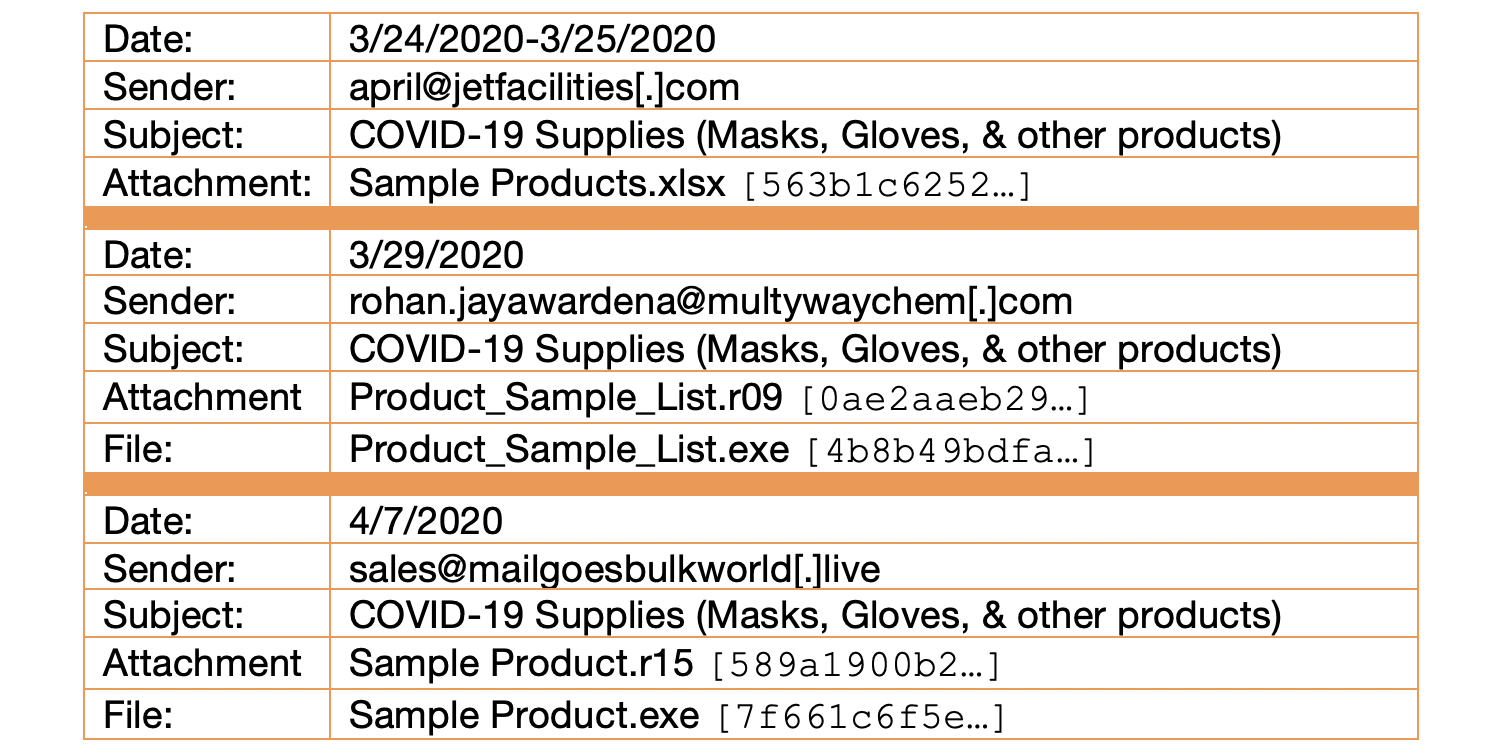

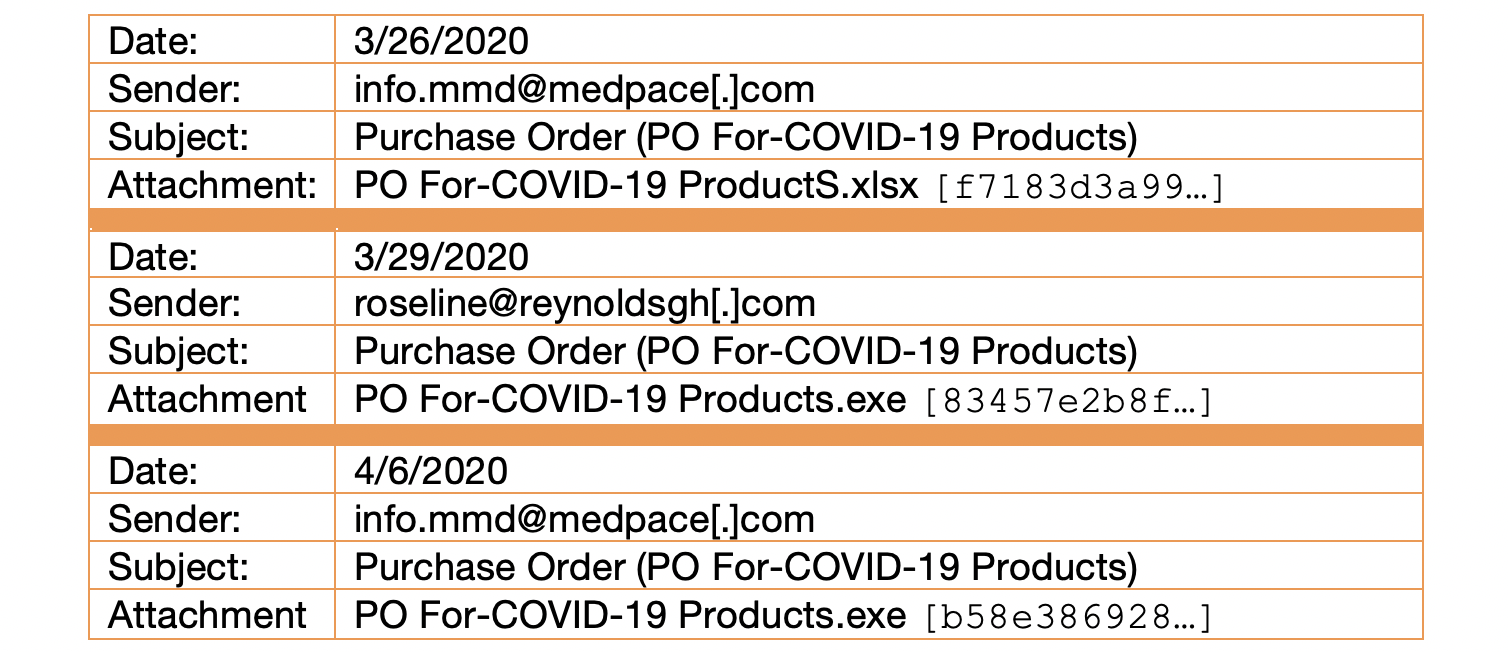

Beginning the next day (March 24) and continuing through April 7, 2020, a fourth, more complex, campaign was observed. This time, three different email accounts were used to send three different malicious attachments. Common amongst all of these phishing attempts was the same email subject relating to COVID-19 supplies. Noting that email subjects are not typically used as a basis for establishing correlation between phishing campaigns, we believe that in this case the uniqueness of the subject (to include identical capitalization and punctuation), combined with similar attachment names and malware families provides a sufficient pattern to suggest that these three events are related.

The first emails were sent to several recipients, including a university in the United States with a large medical program. Consistent with previous campaigns, the attachment was a Microsoft Office document that leveraged the CVE 2017-11882 vulnerability. More specifically, it was a protected Excel file with the blurred heading “Galaxy International Trading Limited” that upon being opened, called out to both mecharnise[.]ir and metadefenderinternationalsolutionfor[.]duckdns[.]org to download additional executables on victim machines.

Next, we saw a single phishing email sent to a Canadian health agency. Setting itself apart from previous samples, this attachment was in fact a sample of AgentTesla packaged as “Product_Sample_List.exe” inside a compressed RAR file. After infecting a potential victim, this file was configured to use SMTP for its command and control with coffiices[.]com.

Finally, the third set of emails were sent to several recipients, including an Australian energy company. Consistent with the previous email, this set once again included a sample of AgentTesla packaged as “Sample Product.exe” inside a compressed RAR file. Additionally, similar to the second campaign, this sample was configured to connect to an account at mailhostbox[.]com for command and control.

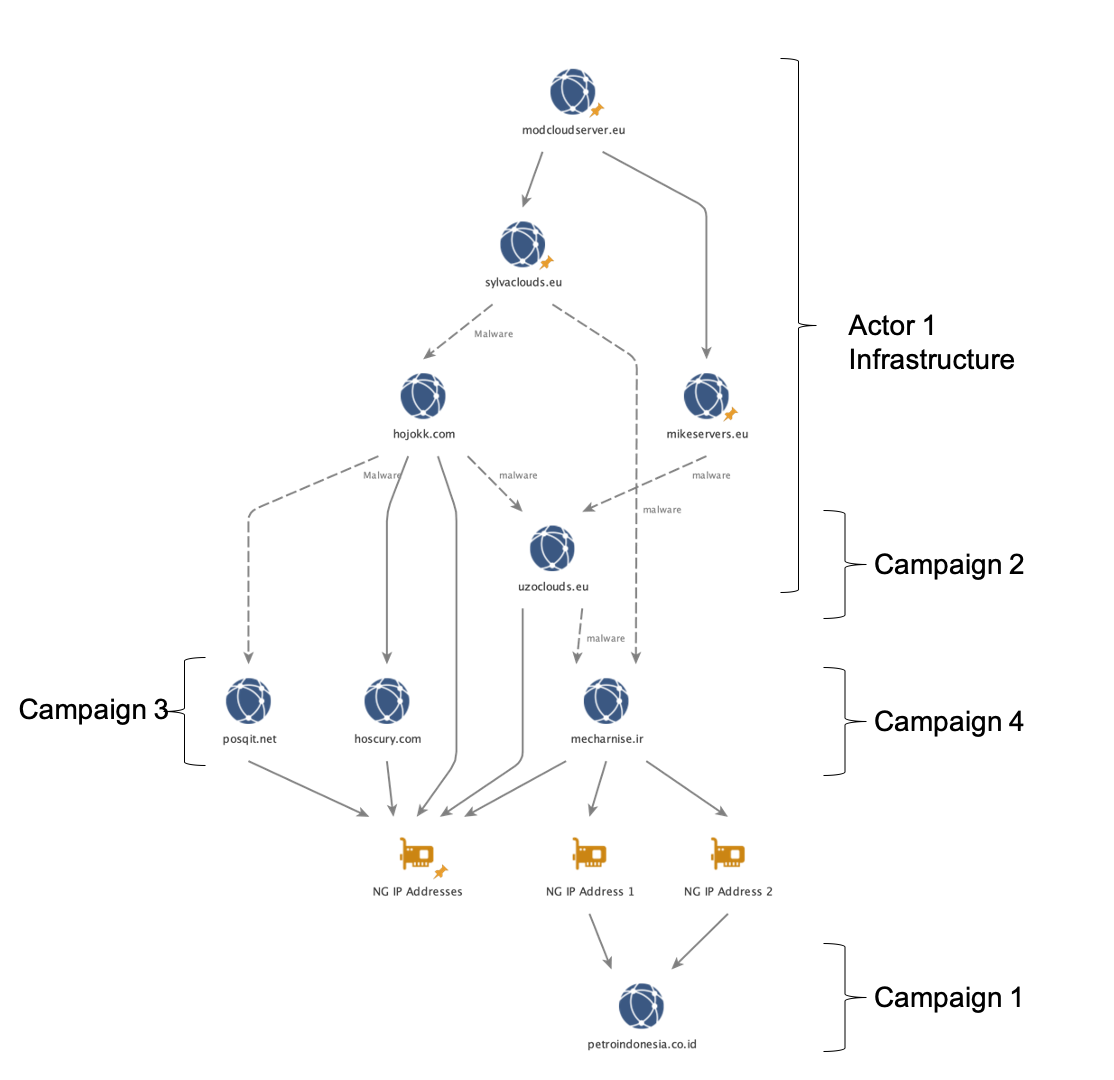

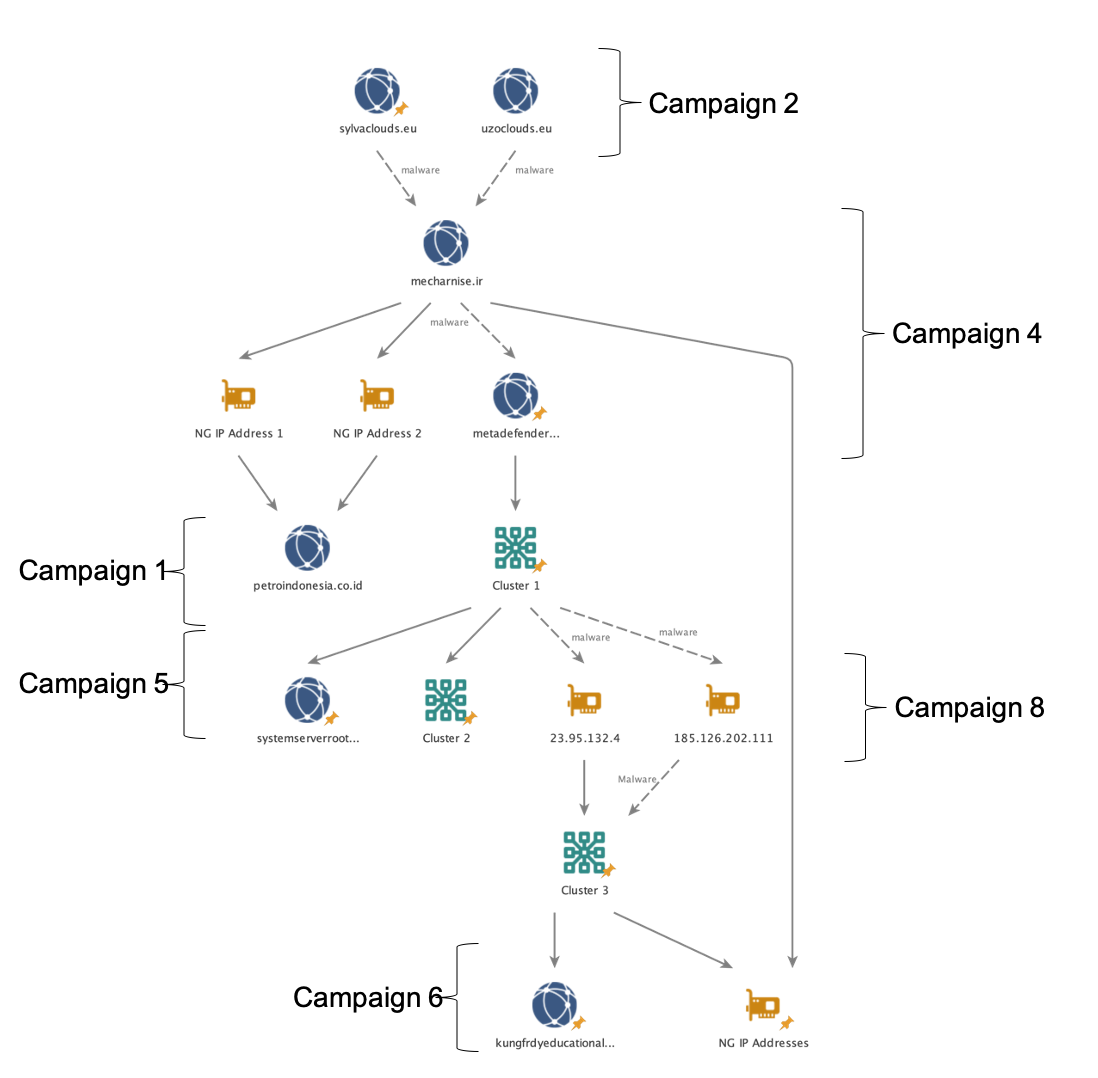

Linking Campaigns 1-4

In examining the connection between Actor 1, Nigerian cybercrime, and these first four phishing campaigns, we found that when malware linkages from these campaigns and historical BEC activity were overlaid with insights afforded by a weakness in Lokibot malware (Malbeacon data), several interesting connections emerged (Figure 2). While not definitive in attributing all of this activity to Actor 1, these connections chart a path originating with Actor 1’s infrastructure, through the infrastructure for these new COVID-19 campaigns, and back to Nigeria.

At the top of our analysis, we start with four European Union (.eu) domains that are directly attributed to Actor 1’s previously identified BEC activity. Solid lines connecting the domains and IP addresses are based on insights provided by the actor’s employment of Lokibot malware, while dashed lines represent the existence of malware samples that connect to both domains. Following the link to hojokk[.]com, we discovered malware hosted in a folder called “MMC.” While we lack insight into Actor 1’s middle name, his first and last initial are coincidently “MC.” Moreover, following additional connections to and from this domain, we discovered several links to Nigeria, as well as malware overlap with posqit[.]net, which we will discuss further in a subsequent campaign below.

Focusing on mecharnise[.]ir, we found malware overlaps with two of Actor 1’s domains. Moreover, we discovered shared Lokibot malware connections to two specific Nigerian IP addresses that both overlap with petroindonesia[.]co[.]id.

Campaign 5

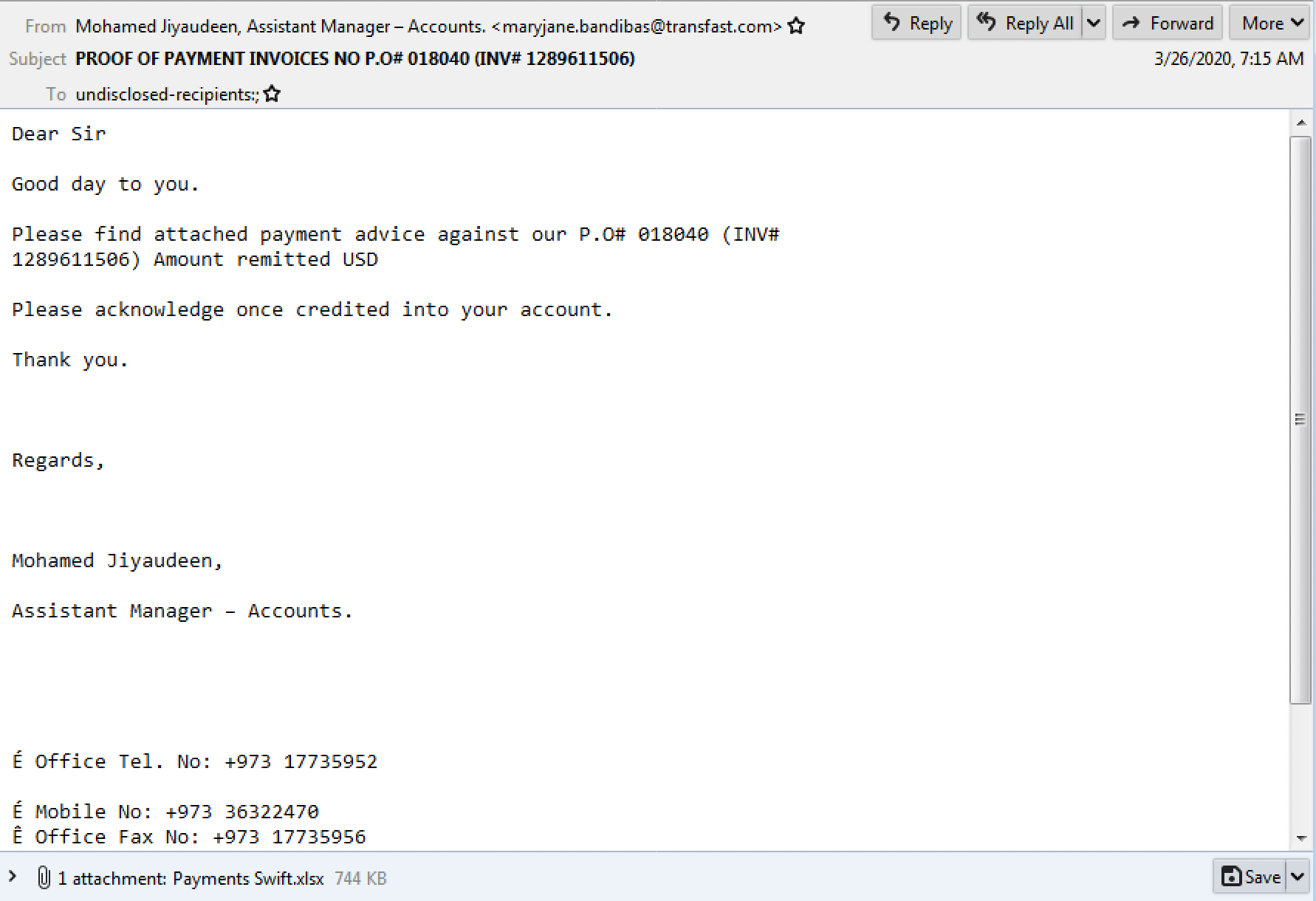

Using these connections as a starting point, we then began our analysis of campaign five, which began on March 26, 2020. Similar to the previous campaign, we noted multiple malware samples and sending accounts, to include spoofing a clinical research organization in the United States.

The first email was seen by a single customer and was packaged once again as a purchase order form for COVID-19-related products. An Excel document was attached and configured to exploit the CVE 2017-11882 vulnerability in order to download and run an executable file mapped to systemserverrootmapforfiletrn[.]duckdns[.]org. Similar to previous campaigns, the downloaded file then connected over SMTP to an account at mailhostbox[.]com. Additionally, it’s worth noting that the Excel attachment was seen in a separate BEC style campaign the same day (see Figures 4. and 5.) and that the document also contained the blurred title of “Galaxy International Trading Limited,” consistent with the fourth campaign. Since the exact same file was sent in multiple phishing campaigns using different themes on the same day, we can assert with greater confidence that these attacks are connected.

On March 29, 2020, a second phishing email was sent to a government agency in the United States with the same subject and filename. However, this time the attachment was AgentTesla malware packaged as an executable file that, once again, connected to an account at mailhostbox[.]com for command and control. Furthermore, this email was sent from the domain reynoldsgh[.]com which maintains an active website that appears incomplete and is potentially fraudulent, with a Ghana phone number listed under contact information.

Campaign 6

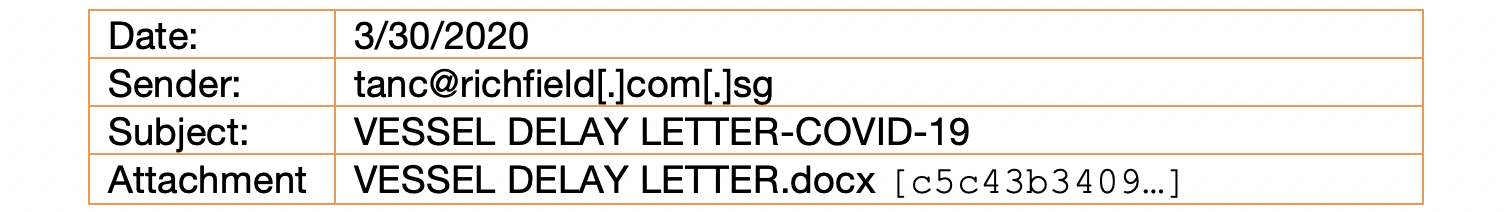

Following an emerging trend of using Dynamic DNS services offered by DuckDNS, on March 30, 2020 we identified a single phishing email disguised as a vessel delay letter from a potentially spoofed shipping company in Singapore. A Word document was attached to the email with a CVE 2017-11882 exploit that called out to kungfrdyeducationalinvestment8agender[.]duckdns[.]org to download another document, and an executable file assessed to be Formbook malware, based on a report by Infoblox.

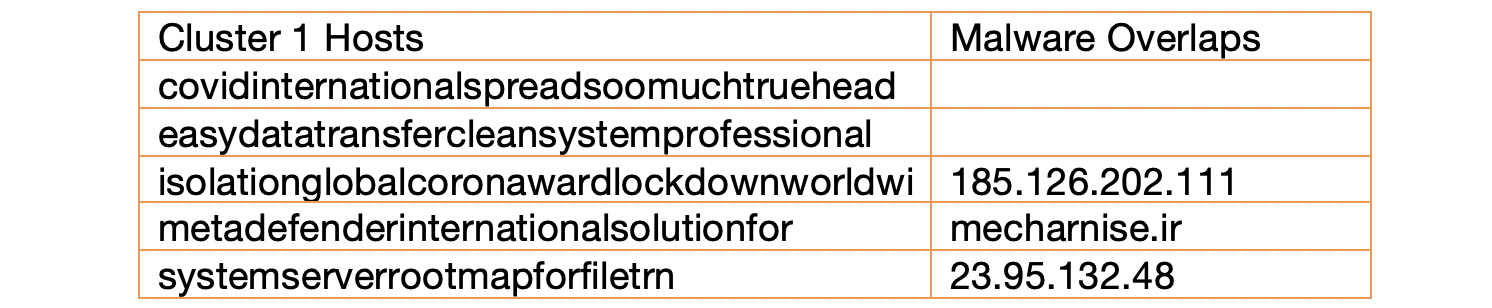

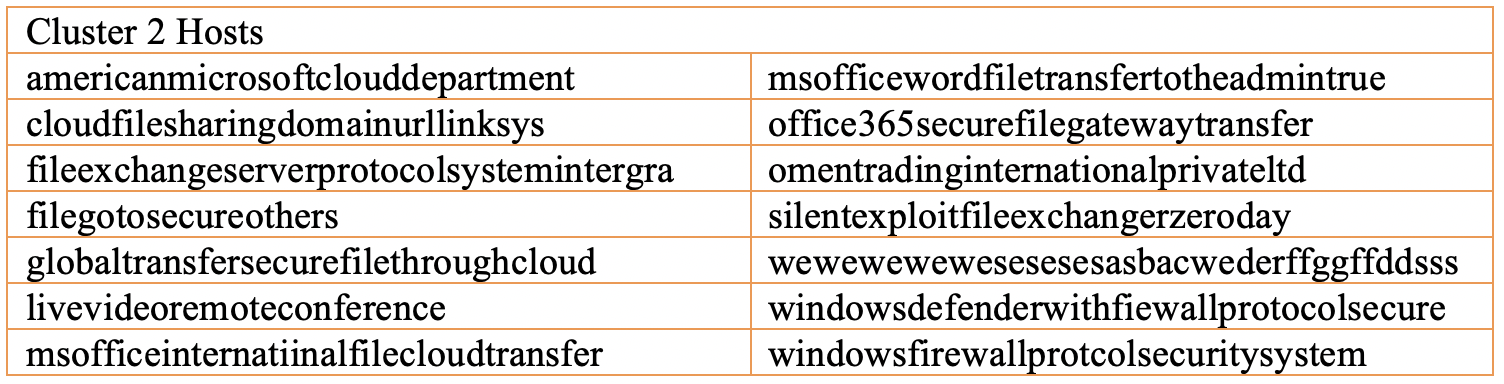

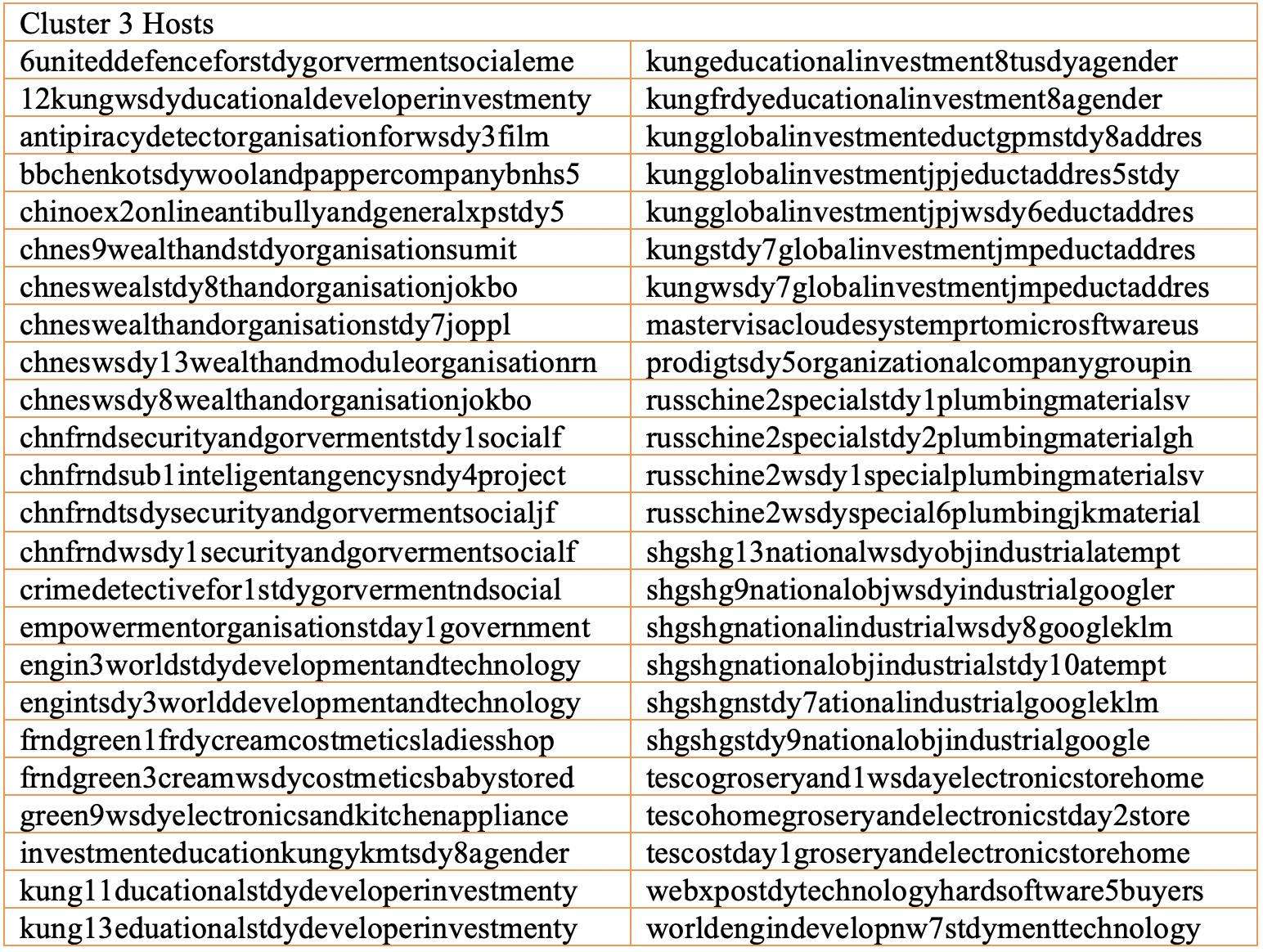

Dynamic DNS Clusters

Deriving linkages from the connections used in campaigns four through six proved exceptionally challenging based on the function and anonymity afforded by dynamic DNS services. However, by pivoting through several layers of obfuscation, we identified three clusters of DuckDNS hosts with links to Nigeria. While difficult to attribute all of this activity directly to Actor 1, the malware overlap seen in the third campaign with mecharnise[.]ir , combined with malware packaging similarities (CVE-2017-11882) and a Nigerian nexus, all lead us to believe that this activity is likely related within one or two degrees of separation from Actor 1.

Starting with metadefenderinternationalsolutionfor[.]duckdns[.]org from the fourth campaign, we quickly found an initial cluster of five hosts that were all related based on an IP connection and their creation dates. Coincidently, this cluster included another host with a COVID-19-related name seen in the fifth campaign: systemserverrootmapforfiletrn[.]duckdns[.]org. Researching these hosts, we found several additional samples of malware packaged as Microsoft Word and Excel documents with the CVE-2017-11882 vulnerability and also found additional malware overlaps.

Further analysis of the IP address connection revealed a second cluster of hosts linked to an additional 71 samples of malware with traditional BEC themes.

Following the malware link between cluster 1 and 23[.]95[.]132[.]48, we discovered that this IP address provided command and control for over 200 samples of Lokibot malware. The vast majority of these samples were configured to call back to a dynamic DNS host in order to download an executable file, before calling out to the IP address for command and control. Pivoting from these samples, we identified a third cluster containing 48 hosts with consistent naming patterns. Interestingly, records show that many of these hosts were established within days of the second cluster, and while they point towards IP addresses in Vietnam, they were initially established using Nigerian infrastructure.

Reviewing the list of hosts in cluster three, the following naming conventions stand out: chnes, engine, kung, russchine, shgshg, and tesco. However, most notably cluster three includes kungfrdyeducationalinvestment8agender[.]duckdns[.]org which we observed in the sixth campaign above.

Campaign 7

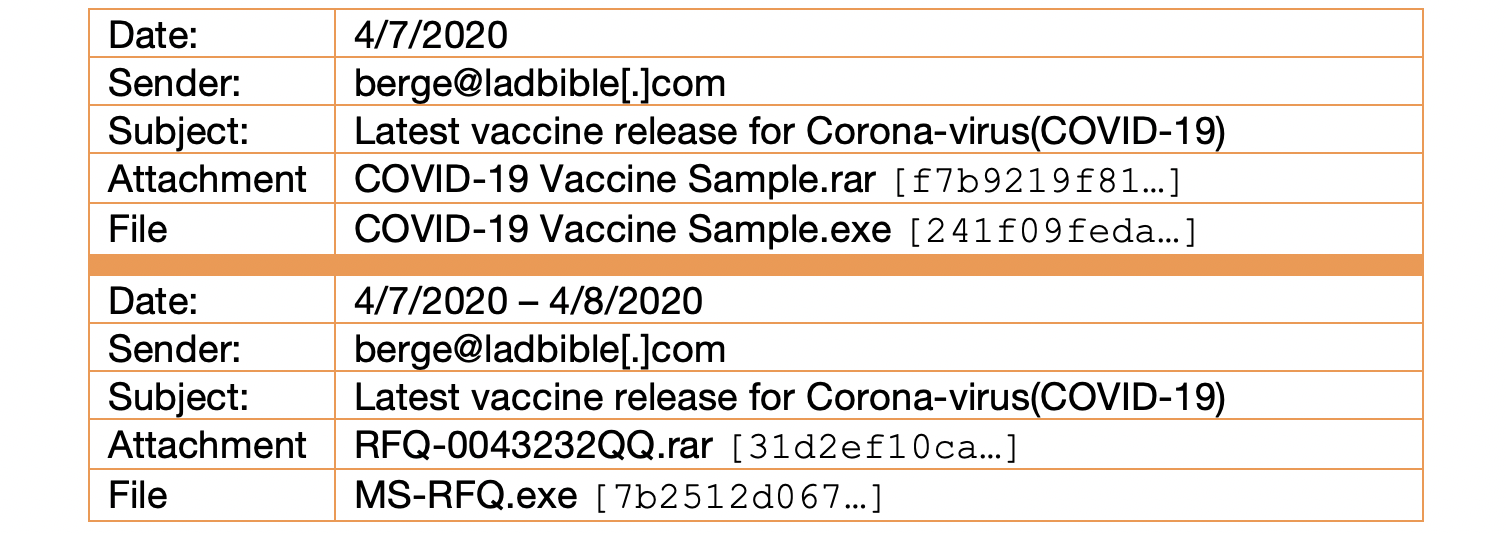

A seventh campaign was launched spanning April 7th and 8th 2020, in which two samples of NanoCore RAT were packaged as compressed RAR files with a vaccine-related lure. These samples were sent to several organizations including a government health agency and two universities with medical programs in the United States, as well as a Canadian health insurer.

Connecting this campaign to Actor 1, we found malicious activity originating from the domain ladbible[.]com dating back to mid-January. Tracing the earliest activity back to Nigerian origins, we also discovered that less than two weeks prior to this campaign, this domain was used to distribute a sample of Lokibot malware. That sample called back to two domains previously attributed to Actor 1 (sylvaclouds[.]eu and hokokk[.]com) and outlined in Figure 3 above.

Campaign 8

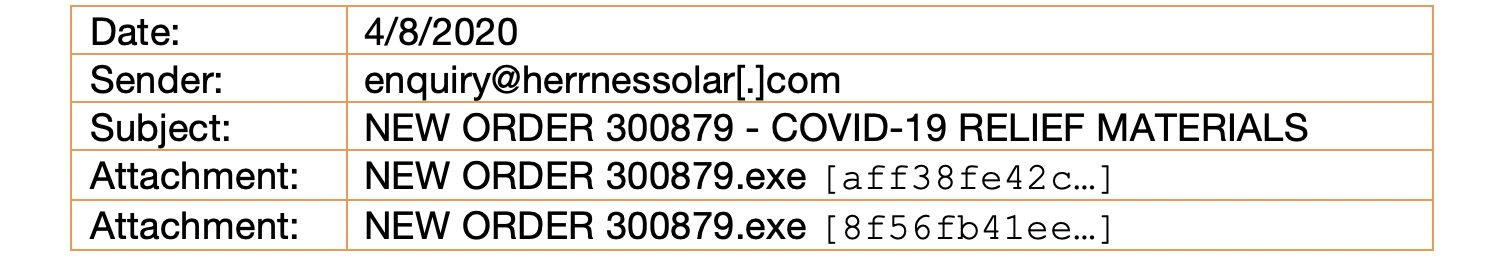

On April 8, 2020, we witnessed the most recent campaign by this actor. Distributed broadly, targets of this campaign included a government health agency, state infrastructure, and a health insurance company in the United States, in addition to a university and regional government in Italy, and various government institutions in Australia. Disguised as COVID-19 relief materials coming from a “Thai Medical Department,” these phishing emails were delivered with one of two samples of Lokibot malware designed to call out to 185[.]126[.]202[.]111 for command and control. As seen in Figure 3 above, analysis performed on this IP address identified malware overlap with dynamic DNS clusters one and three.

Actor 2

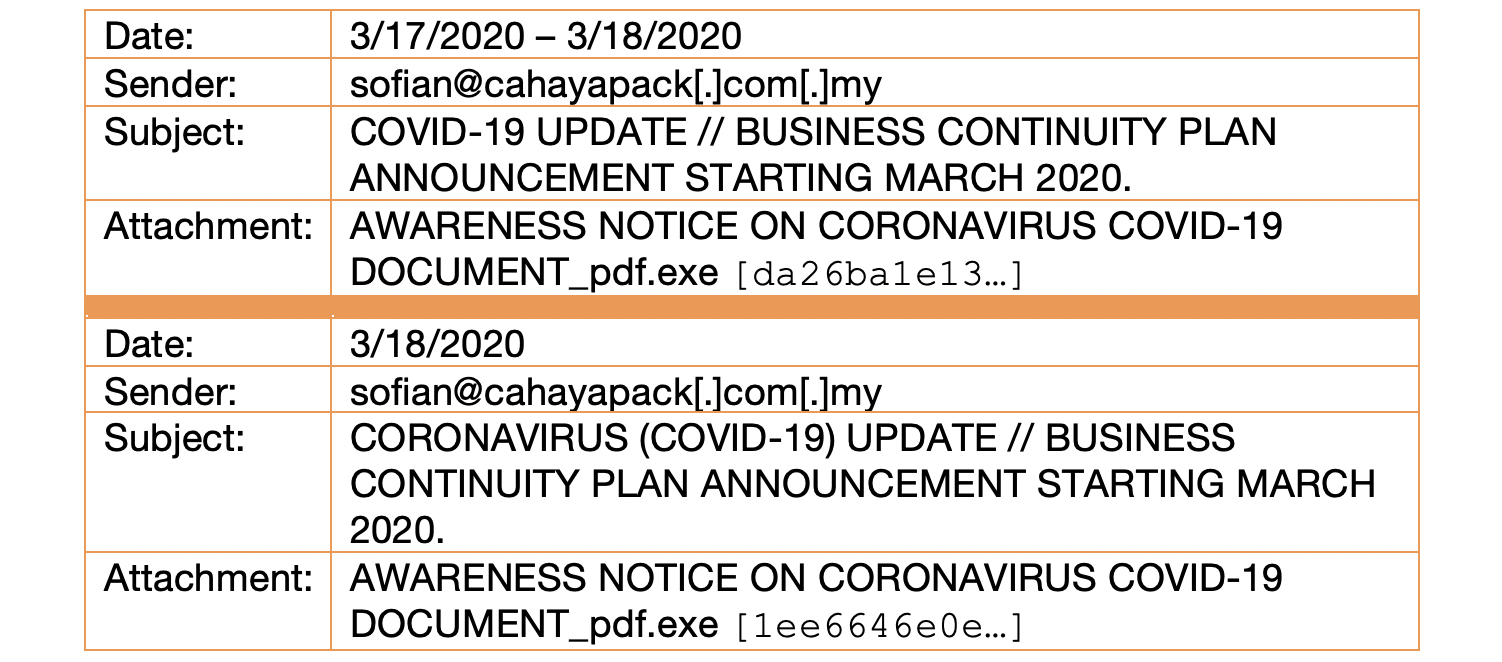

Separate and distinct from the campaigns above, we identified a single campaign associated with the name of Alhaji. Between March 17th and 18th, 2020, two samples of Lokibot malware were sent to several organizations, including a government health agency in the United States. These samples called out academydea[.]com/alhaji/Panel/five/fre[.]php for command and control. Upon researching this domain, we discovered an additional 16 samples of malware used in the previous month. Further, leveraging insights from a vulnerability in Lokibot malware, we were able to trace this activity back to Nigerian IP addresses.

Actor 3

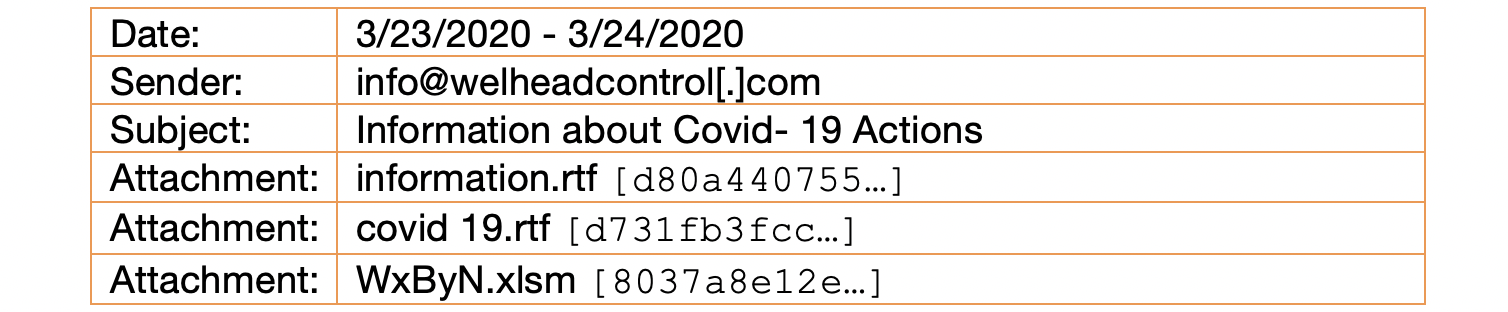

Between March 23rd and 24th, 2020, a SilverTerrier actor using the name Black Emeka launched a series of emails containing malicious attachments. Disguised as COVID-19 information, these emails originated from the domain welheadcontrol[.]com, which is registered to the actor. The attached malware samples use PowerShell to download malicious executable files from the domain goldenlion[.]sg, which resolves to an active website for Golden Lion Technology PTE LTD in Singapore. While likely not a coincidence, the website advertises Goldhofer equipment, while this actor is also the registered owner of the typo variant domain goldhhofer[.]com.

Conclusion

As 2020 progresses, the most prominent threat facing customers is commodity malware deployed in support of sophisticated BEC schemes. Given the global impacts of COVID-19, SilverTerrier actors have begun adapting their phishing campaigns and will likely continue to use COVID-19-themed emails to deliver commodity malware broadly in support of their objectives. In light of this trend, we encourage government agencies, healthcare and insurance organizations, public utilities, and universities with medical programs to apply extra scrutiny to COVID-19-related emails containing attachments. While organizations with appropriate spam filtering, proper system administration, and up-to-date Windows hosts have a much lower risk of infection, we further encourage administrators to validate installation of the Microsoft patch for CVE 2017-11882.

Additionally, Palo Alto Networks customers benefit from the following:

|

Cortex XDR protects endpoints from all malware, exploits and fileless attacks associated with SilverTerrier actors. |

|

WildFire® cloud-based threat analysis service accurately identifies samples associated with these malware families. |

|

Threat Prevention provides protection against the known client and server-side vulnerability exploits, malware, and command and control infrastructure used by these actors to include CVE 2017-11882 |

|

URL Filtering identifies all phishing and malware domains associated with these actors and proactively flags new infrastructure associated with these actors before it is weaponized. |

|

Users of AutoFocus™ contextual threat intelligence service can view malware associated with these attacks using the SilverTerrier tag. |

Indicators of Compromise

Malware Samples

3335ebffd8b4ab739db99f68cd6d79caa39c1210c274bbe4166194cc26de4123

e365100468e9472518d1875796932a8085ab29f6bbfe3357928fa9cc6187628b

27d601ef1a2b340b6b644493a627064f60ad8a95271248e00f7bb54a59abb069

563b1c6252612d06b714bf29b9f53f7aade4c7ac6658b2d0c774a7e244ea83da

0ae2aaeb2938cf4c777be4aa192e4994020609f5640add8e7296de9ff34eb227

4b8b49bdfa435d0faba2e3964b04e20bbfc86aa4ffc3c3b8e1449894892f125b

589a1900b210826e97ec8da3c5c40f707963146e934393eb15e1b07a1398912c

7f661c6f5ebba3eca82e1dbf1a96e27f2503da405093464538d90dc113a7b439

f7183d3a992ead2bf194ac46b1f6f70ad9e30bfd5b6065ffbd96a3529c311725

83457e2b8f9209ec1c987b1a0bee65140cc41d1d59ed38f1d1ad160ea0d1d13c

b58e386928543a807cb5ad69daca31bf5140d8311768a518a824139edde0176f

c5c43b340957830f5d7484ce06f9de0ef593d88f3d48c09cd2150e670661f672

f7b9219f81772e928ab0fbd0becbcf10ca3792ce211bb4a7fa68b41050bdb220

241f09feda09dc33b86e23d317bc2425f4d43b91221815caa5eb055a9a97be74

31d2ef10cad7d68a8627d7cbc8e85f1b118848cefc27f866fcd43b23f8b9cff3

7b2512d06723cc29f80ae8c8d6df141f27bc9d962ae76b5651b84d7be4379bba

aff38fe42c8bdafcd74702d6e9dfeb00fb50dba4193519cc6a152ae714b3b20c

8f56fb41ee706673c706985b70ad46f7563d9aee4ca50795d069ebf9dc55e365

da26ba1e13ce4702bd5154789ce1a699ba206c12021d9823380febd795f5b002

1ee6646e0ea9ceb6fa1721f809bd3cdaeb38c6b2bdd7171b340097c237527568

d731fb3fcc6ecd266251408a282ef4409eac94ce25cecadbfcb2df08e7ca7693

d80a440755dc15803db459b15b991d1abe81054f0942d054d965a578b92917b7

8037a8e12e8cacdaca24b993ffdbd8cdc63ec29dd78eee136083fa09049dbf0c

Domains:

academydea[.]com

coffiices[.]com

goldenlion[.]sg

ladbible[.]com

mecharnise[.]ir

mikeservers[.]eu

modcloudserver[.]eu

petroindonesia[.]co[.]id

posqit[.]net

reynoldsgh[.]com

sylvaclouds.eu

uzoclouds[.]eu

welheadcontrol[.]com

Dynamic DNS Hosts:

12kungwsdyducationaldeveloperinvestmenty[.]duckdns[.]org

6uniteddefenceforstdygorvermentsocialeme[.]duckdns[.]org

americanmicrosoftclouddepartment[.]duckdns[.]org

antipiracydetectorganisationforwsdy3film[.]duckdns[.]org

bbchenkotsdywoolandpappercompanybnhs5[.]duckdns[.]org

chinoex2onlineantibullyandgeneralxpstdy5[.]duckdns[.]org

chnes9wealthandstdyorganisationsumit[.]duckdns[.]org

chneswealstdy8thandorganisationjokbo[.]duckdns[.]org

chneswealthandorganisationstdy7joppl[.]duckdns[.]org

chneswsdy13wealthandmoduleorganisationrn[.]duckdns[.]org

chneswsdy8wealthandorganisationjokbo[.]duckdns[.]org

chnfrndsecurityandgorvermentstdy1socialf[.]duckdns[.]org

chnfrndsub1inteligentangencysndy4project[.]duckdns[.]org

chnfrndtsdysecurityandgorvermentsocialjf[.]duckdns[.]org

chnfrndwsdy1securityandgorvermentsocialf[.]duckdns[.]org

cloudfilesharingdomainurllinksys[.]duckdns[.]org

crimedetectivefor1stdygorvermentndsocial[.]duckdns[.]org

empowermentorganisationstday1government[.]duckdns[.]org

engin3worldstdydevelopmentandtechnology[.]duckdns[.]org

engintsdy3worlddevelopmentandtechnology[.]duckdns[.]org

fileexchangeserverprotocolsystemintergra[.]duckdns[.]org

filegotosecureothers[.]duckdns[.]org

frndgreen1frdycreamcostmeticsladiesshop[.]duckdns[.]org

frndgreen3creamwsdycostmeticsbabystored[.]duckdns[.]org

globaltransfersecurefilethroughcloud[.]duckdns[.]org

green9wsdyelectronicsandkitchenappliance[.]duckdns[.]org

investmenteducationkungykmtsdy8agender[.]duckdns[.]org

kung11ducationalstdydeveloperinvestmenty[.]duckdns[.]org

kung13eduationalstdydeveloperinvestmenty[.]duckdns[.]org

kungeducationalinvestment8tusdyagender[.]duckdns[.]org

kungfrdyeducationalinvestment8agender[.]duckdns[.]org

kungglobalinvestmenteductgpmstdy8addres[.]duckdns[.]org

kungglobalinvestmentjpjeductaddres5stdy[.]duckdns[.]org

kungglobalinvestmentjpjwsdy6eductaddres[.]duckdns[.]org

kungstdy7globalinvestmentjmpeductaddres[.]duckdns[.]org

kungwsdy7globalinvestmentjmpeductaddres[.]duckdns[.]org

livevideoremoteconference[.]duckdns[.]org

mastervisacloudesystemprtomicrosftwareus[.]duckdns[.]org

msofficeinternatiinalfilecloudtransfer[.]duckdns[.]org

msofficewordfiletransfertotheadmintrue[.]duckdns[.]org

office365securefilegatewaytransfer[.]duckdns[.]org

omentradinginternationalprivateltd[.]duckdns[.]org

prodigtsdy5organizationalcompanygroupin[.]duckdns[.]org

russchine2specialstdy1plumbingmaterialsv[.]duckdns[.]org

russchine2specialstdy2plumbingmaterialgh[.]duckdns[.]org

russchine2wsdy1specialplumbingmaterialsv[.]duckdns[.]org

russchine2wsdyspecial6plumbingjkmaterial[.]duckdns[.]org

shgshg13nationalwsdyobjindustrialatempt[.]duckdns[.]org

shgshg9nationalobjwsdyindustrialgoogler[.]duckdns[.]org

shgshgnationalindustrialwsdy8googleklm[.]duckdns[.]org

shgshgnationalobjindustrialstdy10atempt[.]duckdns[.]org

shgshgnstdy7ationalindustrialgoogleklm[.]duckdns[.]org

shgshgstdy9nationalobjindustrialgoogle[.]duckdns[.]org

silentexploitfileexchangerzeroday[.]duckdns[.]org

tescogroseryand1wsdayelectronicstorehome[.]duckdns[.]org

tescohomegroseryandelectronicstday2store[.]duckdns[.]org

tescostday1groseryandelectronicstorehome[.]duckdns[.]org

webxpostdytechnologyhardsoftware5buyers[.]duckdns[.]org

wewewewewesesesesasbacwederffggffddsss[.]duckdns[.]org

windowsdefenderwithfiewallprotocolsecure[.]duckdns[.]org

windowsfirewallprotcolsecuritysystem[.]duckdns[.]org

worldengindevelopnw7stdymenttechnology[.]duckdns[.]org

IP Addresses:

23[.]95[.]132[.]48

185[.]126[.]202[.]111

Palo Alto Networks has shared our findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, in this report with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. For more information on the Cyber Threat Alliance, visit www.cyberthreatalliance.org.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42