Executive Summary

On Dec. 13, the cyber community became aware of one of the most significant cybersecurity events of our time, impacting both commercial and government organizations around the world. The event was a supply chain attack on SolarWinds OrionⓇ software conducted by suspected nation-state operators that we are tracking as SolarStorm. Unit 42 was able to connect this event back to an attack we successfully prevented earlier this year. On Dec. 18, we launched a SolarStorm Rapid Assessment program resulting in more than 600 companies requesting this service within the first four days.

While this is not the first software supply chain compromise, it may be the most notable, as the attacker was trying to gain widespread, persistent access to a number of critical networks. Given the importance of the event, we are publishing a timeline of the attack based on our extensive research into the information available to us and our direct experience defending against this threat. We believe this will be invaluable to cybersecurity professionals in the industry responding to this attack, as well as to other researchers piecing together the event details. And as we learn that this threat actor used additional attack vectors, we urge everyone to share what they know about this attack so that we as a cybersecurity community get a complete picture of it as quickly as possible.

It is important to note that we do not have complete knowledge of when the planning and execution of this campaign began. We do, however, have evidence that SolarStorm command and control (C2) infrastructure was set up as early as August 2019. The first modified SolarWinds software was released in October 2019, and the earliest related Cobalt Strike payload we’ve identified was generated using Cobalt Strike 4.0, which was built in December 2019. We do not know when SolarStorm first compromised the SolarWinds software supply chain or the method by which they accomplished this task.

Additionally, multiple reports indicate that SolarStorm employed additional initial access vectors beyond the compromised SolarWinds software. We are tracking these reports but have not confirmed other techniques used to obtain initial access to networks at this time. Of course, we should expect that an adversary with the capability to execute this campaign could have used many additional means to accomplish their goal.

Those seeking details on how Palo Alto Networks is protecting its customers from this threat, please read our Threat Brief on SolarStorm and SUNBURST containing those details, which is being updated as new information comes to light. The SolarStorm ATOM is also being updated as new details emerge.

SolarStorm Timeline Summary

Researchers reported a supply chain attack affecting organizations around the world on Dec. 13, 2020. This incident involved malicious code identified within the legitimate IT performance and statistics monitoring software, OrionⓇ, developed by SolarWinds.

Since then, details from other security vendors and organizations have been released, further building on the events leading up to the initial disclosure. Unit 42 has conducted research based on what is publicly available and what information has been identified within internal data.

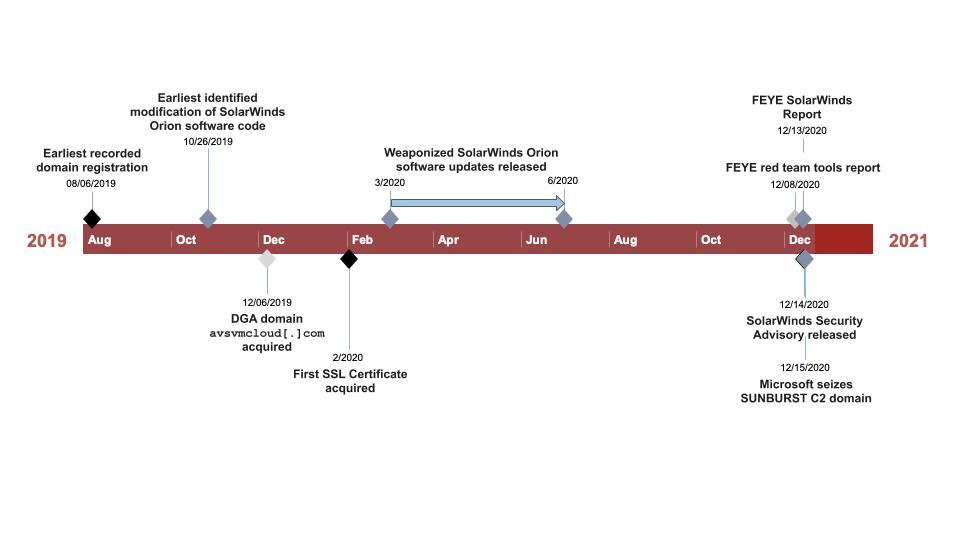

The timeline in Figure 1 displays a high-level summary of the events observed, beginning as early as August 2019 and continuing through December 2020.

Analysis of the SolarWinds software revealed code modification as early as October 2019, although the first weaponized software updates, denoted as SUNBURST malware, were not released until approximately March 2020. Unit 42 has also observed two samples of the modified SolarWinds software which appear as early as October 2019.

The majority of the infrastructure observed in this campaign was acquired between December 2019 and March 2020; however, at least one domain, incomeupdate[.]com, noted in Cobalt Strike BEACON activity, was registered in August 2019 as depicted in Table 1. SolarStorm operators acquired SSL certificates for many of the associated domains between February and April 2020, with at least one certificate extending to July.

The extensive infrastructure build-out throughout this timeline helps to visualize the persistence of the operation from initial targeting to completion of the objective. SolarStorm threat actors are highly skilled and thorough in their operational handling.

To better understand the timing around when organizations installed the malicious SUNBURST update, we reviewed our DNS Security logs for requests to avsvmcloud[.]com, the domain used with a domain generation algorithm (DGA) in this activity. Industry partners ultimately seized this domain in December 2020.

Our search returned responses from April-November 2020. The counts of requests observed in DNS Security logs each month are shown in Figure 2 below.

![The counts of requests for avsvmcloud[.]com observed in DNS Security logs each month. The count peaks in July.](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/word-image-229.png)

Palo Alto Networks Cortex XDR Blocked an Attempted SolarStorm Attack

As our CEO Nikesh Arora described on Dec. 17, Palo Alto Networks Cortex XDR successfully prevented a SolarStorm attack by immediately detecting and preventing an attempt to execute Cobalt Strike Beacon on one of our IT SolarWinds servers last year. To help provide more insight into the timeline around this threat, we are sharing more details about what our security operations center (SOC) observed at that time.

There are three initial phases to an intrusion from SolarStorm:

- A SolarWinds Orion server updates its software and downloads the malicious update containing the SUNBURST backdoor.

- SUNBURST then sends DNS requests to check in with the attacker, which contain information identifying the organization. The attacker chooses to designate some organizations as being of interest for further intrusion.

- For SUNBURST to gain further access into the network, additional steps are needed starting with downloading and executing an additional malicious payload.

The Palo Alto Networks SOC observed a DNS request from our Solarwinds Orion server for the avsvmcloud[.]com domain on Sept. 29, 2020. During this short-lived connection, no malicious content was downloaded but the system was likely labeled for further intrusion.

Six days later, on Oct. 5, 2020, a second connection occurred in which a new payload was downloaded. With the use of Cortex XDR’s Behavioral Threat Protection capability, this payload was instantly detected and the attempt to execute was prevented. Our SOC then immediately isolated the server, initiated an investigation and verified our infrastructure was secure. Additionally, at this time, our SOC notified SolarWinds of the activity observed. The investigation by our SOC concluded that the attempted attack was unsuccessful and no data was compromised.

We thought this was an isolated incident. However, on Dec. 13, when SolarWinds disclosed SUNBURST, it became clear that the incident we prevented was an attempted SolarStorm attack. Given this new information, our SOC exercised due diligence and analyzed our entire infrastructure extensively again to revalidate the security of our entire network. We remain confident that our network continues to be secure.

Observed TEARDROP Activity

Unit 42 has and continues to research this campaign to identify additional details that could lead to further defensive actions.

During analysis of the information available, Unit 42 identified related activity involving TEARDROP malware that was used to execute a customized Cobalt Strike BEACON. This sample contains a beacon request to the previously unreported domain mobilnweb[.]com.

The TEARDROP DLL has a SHA256 of: 118189f90da3788362fe85eafa555298423e21ec37f147f3bf88c61d4cd46c51

and contains a beacon request for the URI /2019/Person-With-Parnters-Brands-Our/ with the User-Agent Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/85.0.4183.83 Safari/537.36. Within that same configuration, we also observed an additional URI setting containing the string /2019/This-Person-Two-Join-With/.

The following watermark setting was also present and appears to be unique to this sample 0x38383430 (943207472). This watermark likely indicates that the operators used a licensed version of Cobalt Strike.

Additional configuration details of interest include:

SETTING_C2_POSTREQ:

Referer: https://yahoo[.]com/

Host: mobilnweb[.]com

Accept: */*

Accept-Language: en-US

Connection: close

name="uploaded_1";filename="91018.png"

Content-Type: text/plain

SETTING_SPAWNTO_X86:

%windir%\syswow64\msinfo32.exe

SETTING_SPAWNTO_X64:

%windir%\sysnative\control.exe

Although the configuration details above show the referer as https://yahoo[.]com, we do not have evidence that Yahoo was used in an actual beacon.

SolarStorm Infrastructure Establishment Timeline

While some of these domains have a registration date earlier than the dates depicted here, the dates shown are the domain modification dates believed to be when the actors acquired control over the domain. The variation in registration date vs. the time of acquisition by SolarStorm provides an added sense of legitimacy for the domains in use.

| Domain | Assessed Actor Controlled Date | Registrar |

| incomeupdate[.]com | 8/6/19 | NameCheap |

| zupertech[.]com | 10/10/19 | NameSilo |

| avsvmcloud[.]com | 12/6/2019 | GoDaddy |

| mobilnweb[.]com | 12/19/19 | NameCheap |

| highdatabase[.]com | 12/26/19 | NameSilo |

| solartrackingsystem[.]net | 1/7/20 | NameSilo |

| webcodez[.]com | 1/15/20 | NameCheap |

| panhardware[.]com | 1/18/20 | NameSilo |

| websitetheme[.]com | 1/27/20 | NameSilo |

| thedoccloud[.]com | 2/5/20 | NameSilo |

| seobundlekit[.]com | 2/6/20 | NameCheap |

| freescanonline[.]com | 2/10/20 | NameCheap |

| deftsecurity[.]com | 2/12/20 | NameSilo |

| virtualwebdata[.]com | 2/13/20 | NameSilo |

| digitalcollege[.]org | 3/5/20 | NameCheap |

| databasegalore[.]com | 3/12/20 | NameCheap |

| zupertech[.]com | 3/15/20 | NameSilo |

| lcomputers[.]com | 6/22/20 | NameSilo |

Table 1. SolarStorm domain acquisition timeline

The following SSL certificates were observed in connection with SolarStorm infrastructure. All certificates are issued by Sectigo RSA Domain Validation Secure Server CA.

| Domain | SHA-1 | Dates Valid |

| websitetheme[.]com | 66576709A11544229E83B9B4724FAD485DF143AD | 2/3/20 - 2/2/21 |

| thedoccloud[.]com | 849296c5f8a28c3da2abe79b82f99a99b40f62ce | 2/6/20 - 2/5/21 |

| seobundlekit[.]com | E7F2EC0D868D84A331F2805DA0D989AD06B825A1 | 2/6/20 - 2/5/21 |

| freescanonline[.]com | 8296028C0EE55235A2C8BE8C65E10BF1EA9CE84F | 2/11/20 - 2/10/21 |

| solartrackingsystem[.]net | 91B9991C10B1DB51ECAA1E097B160880F0169E0C | 2/12/20 - 2/11/21 |

| virtualwebdata[.]com | AB93A66C401BE78A4098608D8186A13B27DB8E8D | 2/13/20 - 2/13/21 |

| deftsecurity[.]com | 12D986A7F4A7D2F80AAF0883EC3231DB3E368480 | 2/13/20 - 2/12/21 |

| digitalcollege[.]org | FDB879A2CE7E2CDA26BEC8B37D2B9EC235FADE44 | 3/5/20 - 3/5/21 |

| databasegalore[.]com | D400021536D712CBE55CEAB7680E9868EB70DE4A | 3/12/20 - 3/12/21 |

| mobilnweb[.]com | 2C2CE936DD512B70F6C3DE7C0F64F361319E9690 | 4/3/20 - 4/3/21 |

| panhardware[.]com | AF6268F675ED810D804745970927E36D12AC9B0A | 4/10/20 - 4/10/21 |

| incomeupdate[.]com | B654148983439E28802166449A8F413B9C995547 | 4/14/20 - 4/14/21 |

| highdatabase[.]com | 35AEFF24DFA2F3E9250FC874C4E6C9F27C87C40A | 4/16/20 - 4/17/21 |

| zupertech[.]com | B80B01AE313C106F70502142F2B2BCFFC7E15ABD | 5/13/20 - 5/13/21 |

| lcomputers[.]com | 7F9EC0C7F7A23E565BF067509FBEF0CBF94DFBA6 | 6/23/20 - 6/24/21 |

| webcodez[.]com | 2667DB3592AC3955E409DE83F4B88FB2046386EB | 7/8/20 - 7/8/21 |

Table 2. SSL certificates associated with SolarStorm domain activity

Additional Tools and Techniques

There have been many reports indicating that SolarStorm used additional techniques and tools with this incident. A summary of our current knowledge of this use is as follows:

VMware

According to recent reporting, VMware has been associated with this attack in two ways.

First, the National Security Agency released an advisory earlier this month about CVE-2020-4006, a command injection vulnerability, stating that Russian state-sponsored actors were actively exploiting the vulnerability and suggesting US Government agencies patch immediately. This vulnerability exists in five VMware software products focused on identity and access management. Exploitation allows attackers to deploy a webshell on the system and gain access to protected data. This vulnerability can only be exploited by someone who has already authenticated to the system and indicates that when leveraged, it likely is used to gain additional access once the attacker is already inside the networks. More information about CVE-2020-4006 can be found in our previously released Threat Brief: VMware Command Injection Vulnerability.

Second, VMware stated they have SolarWinds OrionⓇ systems in their environment, but they have not seen any evidence of exploitation. Unit 42 has not seen any indication that VMware’s software was used as an infection vector or a TTP utilized within the SolarStorm attack.

Microsoft / SAML

Microsoft has published multiple reports on activity related to this attack campaign, including a summary of the backdoor implanted into SolarWinds OrionⓇ (referred to by Microsoft as Solorigate), as well as guidance for their customers on protecting themselves. They have publicly stated they are working with more than 40 companies who have been targeted in this attack.

One specific component of the attack that Microsoft has discussed in detail is what they have observed in compromised networks with regard to identity infrastructure. Specifically, the attackers have exfiltrated SAML token signing certificates that allow them to forge tokens and access any resources trusted by those certificates. Microsoft has observed these forged tokens presented to the Microsoft cloud on behalf of their customers.

The impact of a compromise of these certificates implies the attacker gained the highest level of privileges inside the network and used them to establish long-term access to the network.

SUPERNOVA Webshell

FireEye’s initial report on the SolarWinds compromise included indicators for a webshell they call SUPERNOVA. Since publication, FireEye has removed those indicators as they no longer believe they were used as a result of the SolarWinds software compromise. This webshell may not be related, but it is still vital to defend against it. Unit 42 has already published an analysis of the SUPERNOVA webshell.

MFA Bypass

The SAML token-forging attack described above would allow an attacker to evade multi-factor authentication systems, as in that case, the authentication system itself is compromised. Volexity published a report about a threat group named Dark Halo who they have now connected to SolarStorm. Their report describes that the attacker targeted the “integration secret key” used to connect Cisco’s Duo Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) solution to an Outlook Web Access server. With that key, they were able to pre-compute the token codes necessary for authentication.

Once again, similar to the SAML token-forging attack, this MFA bypass requires a significant compromise of the systems used to authenticate users and would have been performed post-compromise to extend the attacker’s access to the network.

Other Initial Access Vectors

On Dec. 19, CISA updated their alert on this threat to include this note:

“CISA has evidence that there are initial access vectors other than the SolarWinds Orion platform. Specifically, we are investigating incidents in which activity indicating abuse of Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML) tokens consistent with this adversary’s behavior is present, yet where impacted SolarWinds instances have not been identified. CISA is working to confirm initial access vectors and identify any changes to the TTPs. CISA will update this Alert as new information becomes available.”

Unit 42 does not yet know what additional initial access vectors may have been used in this attack. Detecting the forged SAML tokens is a clear indication of a compromise, so it makes sense that if that appears in an environment with no SolarWinds OrionⓇ servers, another route must have existed. We should expect that an adversary with the capability to execute this campaign could have used many additional means to accomplish their goal.

Software Supply Chain Attacks

SolarWinds is not the first developer to have their software supply chain mishandled. At the end of 2017, we published an article titled “The Era of Software Supply Chain Attacks Has Begun,” which laid out previous software supply chain attacks and predicted an increased focus on attacking trusted developers. Below is a summary of these significant events.

- September 2015 – XcodeGhost: An attacker distributed a version of Apple’s Xcode software (used to build iOS and macOS applications), which injected additional code into iOS apps built using it. This attack resulted in thousands of compromised apps identified in Apple’s app store.

- March 2016 – KeRanger: Popular open source BitTorrent client, Transmission, was compromised to include macOS ransomware in its installer. Attackers compromised the legitimate servers used to distribute Transmission, so users who downloaded and installed the program would be infected with malware that held their files for ransom.

- June 2017 – NotPetya: Attackers compromised a Ukrainian software company and distributed a destructive payload with network-worm capabilities through an update to the “MeDoc” financial software. After infecting systems using the software, the malware spread to other hosts in the network and caused a worldwide disruption affecting many organizations.

- September 2017 – CCleaner: Attackers compromised Avast’s CCleaner tool, used by millions to help keep their PC working properly. The compromise was used to target large technology and telecommunications companies worldwide with a second-stage payload.

In September 2019, attackers again likely targeted Avast’s CCleaner tool after gaining access to Avast’s network through a temporary VPN profile. It is not clear whether or not the same operators from 2017 were involved in this incident.

In each case, including the recent SolarStorm activities, rather than targeting an organization directly through phishing or exploitation of vulnerabilities, the attackers chose to compromise software developers directly and use the trust we place in them to access other networks. This can effectively evade certain prevention and detection controls that have been tuned to trust well-known programs.

This pattern of software supply chain compromises will continue, and security teams can not afford to ignore them. Protecting against these attacks is not simple for any enterprise, and those who are responsible for writing and deploying software need to take responsibility for the integrity of that code.

Conclusion

Since the events of the SolarWinds supply chain attack have unfolded, Unit 42 has actively worked to gather full event details using both publicly available information and internal analysis of an attack against our own network that matches event details reported by FireEye.

While we do not have complete knowledge of the full planning and execution of this campaign, analysis thus far has concluded that the activities of SolarStorm began as early as August 2019 during the infrastructure build-out phase of their operation. SolarStorm operators displayed a tactical and persistent method of operation throughout the entire attack cycle.

While SolarStorm is capable of utilizing many techniques to accomplish their goal, details on initial access vectors beyond the compromised SolarStorm software have not yet been confirmed.

For additional details on how Palo Alto Networks is protecting its customers from this threat, please refer to our Threat Brief on SolarStorm and SUNBURST, which is being updated as new information comes to light.

Palo Alto Networks has shared our findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, in this report with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. For more information on the Cyber Threat Alliance, visit www.cyberthreatalliance.org.

Additional Resources

SolarStorm Threat Brief – Unit 42, Palo Alto Networks

VMware Vulnerability Threat Brief – Unit 42, Palo Alto Networks

SUPERNOVA Webshell – Unit 42, Palo Alto Networks

Software Supply Chain Attack Predictions – Palo Alto Networks

SolarWinds Rapid Response – Palo Alto Networks

VMware Vulnerability Report – Krebs on Security

Dark Halo SolarWinds Compromise – Volexity

Updates on SolarWinds Compromise – Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency

VMware Vulnerability Cybersecurity Advisory – National Security Agency

SUNBURST Malware Countermeasures – FireEye

SolarWinds Compromise Research – FireEye

Cyber Attack against FireEye – FireEye

SolarWinds Supply Chain Attack – ReversingLabs

CCleaner Targeting 2019 – Avast

Solorigate Analysis – Microsoft

Guidance on SolarWinds Activity – Microsoft

DGA Domain Takedown – ZDNet

SolarWinds Compromise Initial Timing – SecurityScorecard

Updated Jan. 17, 2021, at 4:45 p.m. PT.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42