Overview

LockCrypt, also known as EncryptServer2018, is a ransomware family that has been in the wild since mid 2017 and is still active today. The malware was reversed and analyzed thoroughly by Malwarebytes Labs in April, which correctly concluded that the unsophisticated home-made encryption used in this malware seems to be breakable.

However, the Malwarebytes researchers did not publish any decryptor for this malware, and we couldn't find any other public decryption method online either. The only other clue was a news post which referred victims to Michael Gillespie (@demonslay335) for help with its decryption.

We contacted Michael, who did some really nice work together with @hasherezade and @FraMauronz, but whose recovery method was incomplete – it required a large known plaintext file (1MB), could not recover all filenames, and in some cases could not decrypt 1-2 bytes in the end of the file.

In this blog post we will describe our analysis of the home-made encryption that the malware used, how we broke it, and how the encryption key can be recovered in case you have at least 25KB of known plaintext. This scenario is very realistic, since LockCrypt encrypts all of the files it can find, including application files like DLLs which can be easily recovered by installing the same software version on a different computer. Scripts and instructions for recovering files are included in the final section of the report.

Note that a new variant of this malware with better encryption has recently been spotted. We have not analyzed this new version, but it appears to use much stronger encryption.

Initial analysis

Disassembling the malware encryption, we found that the malware authors chose to encrypt the files using some custom-made encryption which looked pretty weak. It really surprised us that in 2018 you could still encounter a ransomware with custom encryption models, when you can easily use Windows APIs to encrypt data in a way that will take billions of years to crack using current and foreseeable hardware (for example for 128-bit AES with a key that was generated using cryptographically safe methods).

The disassembly of the encryption functions is equivalent to the following Python code (equivalent C code for the encrypt() function can be seen in Malwarebyte’s analysis and might be easier to understand because of the pointer operations):

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 |

def grouper(iterable, n, fillvalue=None): """returns a generator which iterates iterable in groups of size n. in case the last group is incomplete, it is padded with fillvalue""" args = [iter(iterable)] * n return itertools.izip_longest(fillvalue=fillvalue, *args) def rol(val, n, width): """equivalent to the x86 rol opcode""" return (val << n) & ((1<<width)-1) | \ ((val & ((1<<width)-1)) >> (width-n)) def encrypt(key, plain): size = len(plain)-2 enc = io.BytesIO(plain) # phase 1 key_cyclic = grouper(itertools.cycle(key), 4) for _ in xrange(0, size&(~0x3), 2): # align the size of the data to a multiple of 4 bytes # get the next key dword k = "".join(key_cyclic.next()) k = struct.unpack("<I", k)[0] # get the next data dword d = enc.read(4) d = struct.unpack("<I", d)[0] # XOR them and put it back to the data e = k^d e = struct.pack("<I", e) enc.seek(-4, os.SEEK_CUR) enc.write(e) # go back 2 bytes in the data stream (so that loop iterations overlap) enc.seek(-2, os.SEEK_CUR) # phase 2 enc.seek(0, os.SEEK_SET) key_cyclic = grouper(itertools.cycle(key), 4) for i in xrange(0, size&(~0x3), 4): # get the next key dword k = "".join(key_cyclic.next()) k = struct.unpack("<I", k)[0] # get the next data dword d = enc.read(4) d = struct.unpack("<I", d)[0] # rotate the data dword e = rol(d, 5, 32) # XOR it with the key dword e = e^k # swap the byte order e = struct.pack(">I", e) # put the data dword back enc.seek(-4, os.SEEK_CUR) enc.write(e) return enc.getvalue() def encrypt_file(key, file): # len(key) == 25000 # leave the first 4 bytes as-is file.seek(4, os.SEEK_SET) # encrypt the rest of the first 1MB of the file plain_data = file.read(0x100000 - 4) enc_data = encrypt(key, plain_data) file.seek(4, os.SEEK_SET) file.write(enc_data) # leave the rest of the file as is |

The following conclusions are apparent:

- The transformation defined by phase 1 is cyclic with a cycle length of 12500 bytes

- The transformation defined by phase 2 is cyclic with a cycle length of 25000 bytes

- Excluding edge cases (we’ll discuss those later on), each plain bit is XOR-ed to 3 key bits (two during phase 1 and another one during phase 2)

- If we "undo" the bit shifts done in Phase 2 (swapping back the byte order and ROR-ing back 5 bits), both phases together can be described as a stream cipher with a cyclic key of length 25000 (which is a function of the original key)

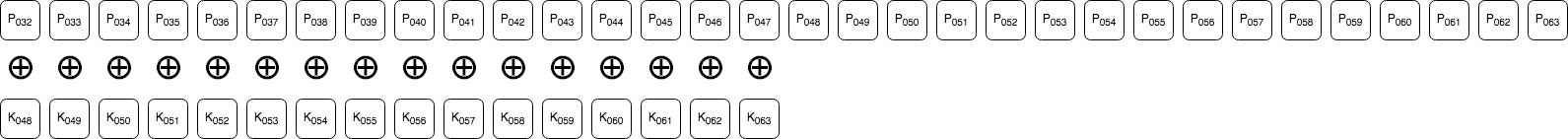

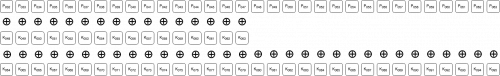

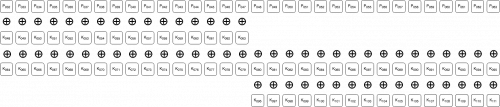

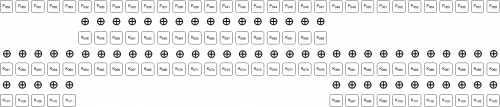

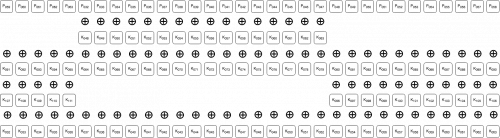

We will explain the last two conclusions using the following diagrams which visualize the transformation of data bytes 4:8 while going through the different steps of the encryption function. The ⊕ symbol between the rows indicates the bits have been XOR-ed with eachother.

Before any sort of transformation, the bits of bytes 4:8 look like:

![]()

After the 2nd iteration of the phase 1 loop:

After the 3rd iteration of the phase 1 loop:

After the 4th iteration of the phase 1 loop (and the same after the entire phase 1 loop):

During the 2nd iteration of the phase 2 loop, after the ROL operation:

During the 2nd iteration of the phase 2 loop, after the XOR operation:

The order of the bytes is then swapped, and this concludes these bytes' encryption.

Recovering the “stream key”

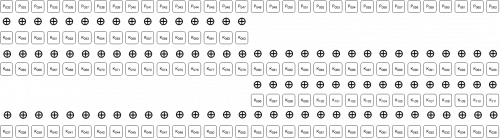

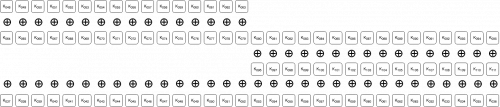

If we take the encrypted bytes 4:8 from the last diagram, unswap their order, and ROR them back 5 bits, we get:

This operation (unswapping the byte order and ROR-ing back 5 bits) has basically "normalized" the encryption to a typical stream cipher. If we then XOR these bytes with known plain bytes, we'll be left with the function of the key bits that we mentioned in conclusion 4 above:

We call this stream (whose each bit is actually three XOR-ed "original key" bits) the "stream key". Since it is cyclic with a cycle length of 25000 bytes, it seems enough to have 25000 bytes of both plain and encrypted bytes in order to recover it and then decrypt the file!

The following python function can be used to recover the stream key using some given plaintext and encrypted data pairs. The index parameter specifies the index of the 25000 known plaintext bytes in the given string (minus 4, since the first 4 bytes are never encrypted), i.e. only bytes idx+4:idx+4+25000 in the plain string will be used.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 |

key_len = 25000 def ror(val, n, width): return ((val & ((1<<width)-1)) >> n) | \ (val << (width-n) & ((1<<width)-1)) def recover_stream_key(plain, enc, idx): assert len(plain) == len(enc) assert len(plain) >= 4 + idx + key_len plain = io.BytesIO(plain) enc = io.BytesIO(enc) assert plain.read(4) == enc.read(4) plain.seek(idx & (~3), os.SEEK_CUR) enc.seek(idx & (~3), os.SEEK_CUR) stream_key = io.BytesIO() for i in xrange(0, key_len + (idx % 4), 4): # read the next plain dword p = plain.read(4) p = struct.unpack("<I", p)[0] # read the next encrypted dword and undo the bit shifts on it e = enc.read(4) # unswap the byte order e = struct.unpack(">I", e)[0] # ROR back 5 bits e = ror(e, 5, 32) # XOR the plain and normalized encrypted dwords k = p^e k = struct.pack("<I", k) # write the stream key dword to the recovered stream key stream if i == 0: stream_key.write(k[idx % 4:]) elif i < key_len: stream_key.write(k) else: # i == key_len stream_key.write(k[:-idx % 4]) stream_key = stream_key.getvalue() assert len(stream_key) == key_len return stream_key |

We should now (not really) be able to decrypt files with the following function:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 |

def decrypt(stream_key, enc): size = len(enc) - 2 plain = io.BytesIO(enc) stream_key_cyclic = grouper(itertools.cycle(stream_key), 4) for i in xrange(0, size&(~3), 4): # read the next stream key dword sk = "".join(stream_key_cyclic.next()) sk = struct.unpack("<I", sk)[0] # read the next encrypted dword and undo the bit shifts on it e = plain.read(4) # unswap the byte order e = struct.unpack(">I", e)[0] # ROR back 5 bits e = ror(e, 5, 32) # XOR the normalized encrypted dword with the stream key dword to recover # the plain dword p = e^sk p = struct.pack("<I", p) plain.seek(-4, os.SEEK_CUR) plain.write(p) return plain.getvalue() def decrypt_file(stream_key, file): assert len(stream_key) == key_len # leave the first 4 bytes as-is file.seek(4, os.SEEK_SET) # decrypt the rest of the first 1MB of the file enc_data = file.read(0x100000 - 4) plain_data = decrypt(stream_key, enc_data) file.seek(4, os.SEEK_SET) file.write(plain_data) # leave the rest of the file as is |

Unfortunately, the above solution excludes the handling a few edge cases:

- The first 2 encrypted bytes (bytes 4:6 of the original file) are only XOR-ed with 2 key bits, and therefore:

- In order to decrypt the rest of the bytes we must use a stream key of idx >= 2

- In order to decrypt the first two bytes we must use the stream key of idx == 0

- If the length of the original file != 2 (mod 4), we will have len(plain) != 0 (mod 4) in encrypt(), and therefore we will have 1-2 bytes in the end of the file encrypted only by the last iteration of phase 1. Each plain bit of those bytes will be XOR-ed with only 1 key bit (which we don't have) and so we cannot decrypt them.

Moreover, as indicated by Malwarebytes the filenames are encrypted by XOR-ing directly with a subset of the original key, and we won't be able to decrypt them as well. A filename of length m can be decrypted if we have a known filename of length n >= m, as @demonslay335 uses in their decryptor.

To conclude, in order to recover any arbitrary length file and filename, it looks like we actually have to recover the original encryption key and not just the stream key we described.

Recovering the original key

The analysis we showed above in fact gave us linear equation system (over GF(2), in which XOR is the addition operation) which tie the stream key with the original key. If we try to generalize the analysis, the following python function can give us the original key bit indices which XOR-ed together result in each stream key bit (indexed by i):

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

key_bitlen = 25000*8 def k_for_i(i): i_dword = i >> 5 # the index of the dword for bit i i_offset = i % 32 # the index of bit i in its dword i = i + key_bitlen k = [] k.append((i_dword << 6) + i_offset) if i_offset < 16: k.append(k[0] - 16) else: k.append(k[0] + 16) k.append((i_dword << 5) + ((i_offset + 5) % 32)) return [x % key_bitlen for x in k if x >= 0] |

That is, stream_key[i] == reduce(xor, (key[k] for k in k_for_i(i)))

With this function, we can generate a very sparse 200000x200000 matrix over GF(2) which will describe the transformation between the original key and the stream key:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

def gen_equations(idx): A_i_j_s = [] for i in xrange(idx << 3, (idx << 3) + key_bitlen): A_i_j_s.append(k_for_i(i)) return A_i_j_s |

That is, row i of the matrix A is all 0s except for the columns in A_i_j_s[i] (which are 1).

This is a VERY sparse matrix (each row contains only 3 values) and so it is feasible to solve it on a regular PC using linear algebra methods. For example, using the mathematics software SageMath, we can do the following:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 |

# fix the following parameters to those of your own stream_key_idx = 25000 # the stream key idx you recovered stream_key_path = "key-stream-idx-25000.bin" # the path to the stream key you recovered original_key_path = "key.bin" # the path to write the original key to import itertools import struct def grouper(iterable, n, fillvalue=None): args = [iter(iterable)] * n return itertools.izip_longest(fillvalue=fillvalue, *args) def str2bits(s): bits = [] for dword in grouper(s, 4): dword = "".join(dword) dword = struct.unpack("<I", dword)[0] bits += [(dword >> i) & 1 for i in xrange(32)] return bits def bits2str(bits): s = [] for dword_bits in grouper(bits, 32): dword = 0 for i, bit in enumerate(dword_bits): dword = dword | (bit << i) s.append(struct.pack("<I", dword)) return "".join(s) with open(stream_key_path) as f: stream_key = f.read() assert len(stream_key) == 25000 stream_key_bits = str2bits(stream_key) Y = vector(GF(2), 200000, stream_key_bits) # create a matrix with the equations for the stream key bit A_i_j_s = gen_equations(stream_key_idx) A = matrix(GF(2), 200000, sparse=True) for i, A_i_j in enumerate(A_i_j_s): for j in A_i_j: A[i,j] = 1 # recover the original key bits X = A.solve_right(Y) key_bits = [int(x) for x in X.list()] key = bits2str(key_bits) with open(original_key_path, 'wb') as f: f.write(key) |

Note that the above function assume for simplicity that idx >= 2 and that the last bytes that were used to recover the stream key were encrypted by both phase 1 (two rounds) and phase 2, that is: len(plain) >= 4 + ((idx + key_len + 3) & ~3) . The code can be fixed to address these special cases, but we did not think it was interesting.

Decrypting your files

To summarize, the steps to recover the encryption key used by the malware:

- Recover a plaintext (unencrypted) version of a file which was encrypted by the ransomware and is at least 25010 bytes of size

- We recommend doing that by installing the same software version of some software that was encrypted by the ransomware on a different computer, and try to match an encrypted DLL file to its original using their file sizes

- Install Python 2.7 if not already installed

- Use the recover_stream_key.py script from the link below to recover the stream key for a certain idx >= 2 from a given pair of encrypted and plaintext files.

- As stated above, we recommend using idx = 25000 if you have a large enough known plaintext file

- Install SageMath

- Open a SageMath Jupyter Notebook, paste the code snippet above, and execute it to recover the original encryption key

- IMPORTANT: Make sure to fix the 3 parameters on the top of the snippet to those of your own before running

- From our experiments, this step may take between 20 minutes to a few hours

- Use the decryptor.py script from the link below to decrypt the encrypted files

We truly hope that any victims of this ransomware will find this analysis and scripts useful in recovering their lost files.

You can find both scripts here within Unit 42's GitHub.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42