Introduction

In December 2016 I posted the first part of this series of blogs introducing the EMEA regional threat reports that I have been authoring and publishing internally for the last 6 months of 2016. I also introduced the EMEA region at a high level– abundant in countries each with mixed languages, cultures and cyber security maturity levels, with different industry sectors and with different economic profiles. A very diverse environment with rich pickings for cyberattacks.

In that post, I also established the structure for these posts: An overview of specific overall trends for the region, a focus on two sets of three countries (in the first report these were the United Kingdom, Germany and France and Turkey, Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates), a conclusion and cyber hygiene recommendations.

Continuing on from the first blog I will discuss here the threat landscape from late last year and into 2017 for another two sets of countries:

- The Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, and Belgium

- Italy, Spain, and Switzerland

Headlines

- We’ve seen LuminosityLink RAT (Remote Access Trojan) variants with ties to the SilverTerrier campaign in the Service Provider sector.

- Uptick in KINS malware campaigns targeting Insurance and Finance sectors in Italy.

- Samples exhibiting suspicious HTTP communication behavior of lacking a user-agent continue to rise.

- Locky ransomware still around but somewhat shadowed by Cerber uptick.

Malicious Behaviors

Before getting into the details of the threat landscape in the chosen countries below I wanted to spend a little time discussing malicious behaviors.

Awareness of behaviors exhibited by programs running in your environment can arguably be as important, if not more so, then knowing whether said programs are malicious or not, or indeed, which family they belong to if they are determined malicious. This can be compounded by the fact that often the same behaviors are exhibited by multiple types and families of malware. In other words, looking at behaviors can have a broader, more generic value. When WildFire analyzes a sample collected from our platform, we not only track what verdict it returns (malware or greyware or benign) but also which malware family the sample belongs to and what behaviors, whether malicious or not, they exhibit.

Monitoring these behaviors and their trending over time can be incredibly useful in understanding the Tools, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) of the attacker. They indicate trends of features adopted by malware authors and how they may be trying to subvert security solutions, for example by smuggling malicious network traffic amongst legitimate application traffic, or take advantage of applications to launch secondary payloads, for example by launching Microsoft PowersShell commands from Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) stored in Microsoft Word documents. These behaviors are elements of the adversary’s playbook, which they are running against their victims.

Understanding an adversary’s playbook can help you improve your organization’s security posture. By understanding popular and prevalent malicious behaviors one can take countermeasures through updating of security policies to prevent or limit the behavior’s capability. These countermeasures may be effective against many adversaries who employ the same TTPs.

One such example is the suspicious behavior tag used in AutoFocus called HttpNoUserAgent. This tag identifies programs that create HTTP traffic but omit, or use blank, user-agent field data. Typically, legitimate applications will include a user-agent value in HTTP requests to tell the web server what type of application they are communicating with, which may result in different data returned by the server. HTTP requests without the user-agent header, or with a blank user agent value, are extremely suspect. Searching for programs that are tagged as such often cover multiple malware families and can provide great visibility in your environment. More and more samples detonated in Wildfire recently have been tagged as exhibiting the HttpNoUserAgent ![]() behavior.

behavior.

The Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, and Belgium

These four countries share some borders: the Netherlands to Belgium where the capital city Brussels contains the headquarters for North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) as well as the European Commission and European Council, and is often referred to as the de facto capitol of the European Council. Further north, forming part of the Nordics region, Denmark borders Sweden, which is one of a small number of European Union countries that are not part of NATO. According to some reports Sweden stayed out of NATO in solidarity with its neighbor Finland, which stayed out in order not to antagonize Russia.

Of the malicious network sessions seen on our next-generation security platforms within these four countries, the sessions in the Netherlands accounted for almost three quarters and when comparing the numbers for actual malware samples used in those sessions, approximately one third of the samples were seen in the Netherlands. Belgium was next and saw almost the same number of samples as the Netherlands but over far fewer sessions, a ratio difference that could imply slightly less large-scale malspam campaigns occurred in Belgium compared to the Netherlands.

Sweden and Denmark saw similar numbers of samples and sessions to each other but despite this some malware families seen in these countries were unique as compared to Belgium and the Netherlands. Sweden was an exception of the four countries as it received more malicious sessions in the second part of the period as opposed to the first.

Although all four countries except Sweden saw some Cerber ransomware activity Belgium saw the highest number of malicious sessions ![]() by far. Generally speaking there has been a global uptick of Cerber ransomware over this time period, and certainly in higher volumes than Locky ransomware, which has been trending

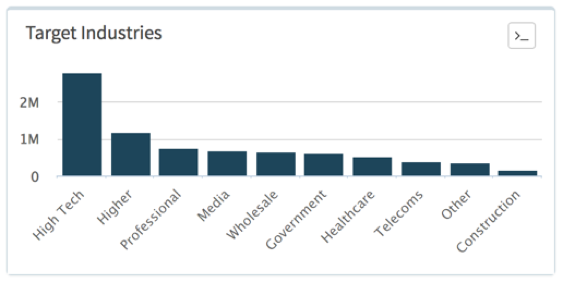

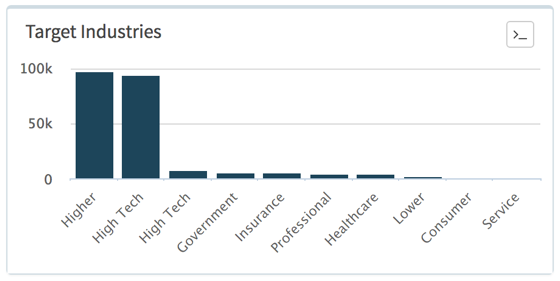

by far. Generally speaking there has been a global uptick of Cerber ransomware over this time period, and certainly in higher volumes than Locky ransomware, which has been trending ![]() down recently but was seen in all four of the countries, albeit in lower volume. The figures below are taken from AutoFocus and compare the industry sectors that see the majority of these two ransomware families. Figure 1 shows Locky while Figure 2 shows Cerber. You can see that the total volume of Locky dwarfs that of Cerber despite the recent downward trend. High Tech and Higher Education tend to see the majority of attacks and while there are other similarities, the main differences, at least in this time period, include Government being higher for Cerber and Professional and Legal Services being lower, and Telecoms being affected by Locky only conversely the Insurance sector only by Cerber.

down recently but was seen in all four of the countries, albeit in lower volume. The figures below are taken from AutoFocus and compare the industry sectors that see the majority of these two ransomware families. Figure 1 shows Locky while Figure 2 shows Cerber. You can see that the total volume of Locky dwarfs that of Cerber despite the recent downward trend. High Tech and Higher Education tend to see the majority of attacks and while there are other similarities, the main differences, at least in this time period, include Government being higher for Cerber and Professional and Legal Services being lower, and Telecoms being affected by Locky only conversely the Insurance sector only by Cerber.

Figure 1 Top industries targeted by Locky

Figure 2 Top industries targeted by Cerber

While these families have been, or currently are, the top of the charts when it comes to prevalence, there are over 100 families being tracked by Unit 42 some of which are creating new and novel techniques to extort the ransom. Some examples include RanserKD aka Crylocker ransomware which communicates victim infection details through appending data to PNG image files uploaded to online services such as Imgur and Dropbox where the attacker can gain the details necessary. This is clearly a move to try and smuggle the malicious network traffic through legitimate-looking traffic patterns. Others include the concept of Doxware or Doxing whereby victim data would be exfiltrated prior to local encryption with the threat of exposing information online that may also cause the victim to pay the ransom over concerns of privacy or company-sensitive information being exposed.

Of the malware families, common to all four countries, Hancitor was certainly one of the most prevalent, ![]() with fairly high session volume in each country though not as sustained or consistent as the aforementioned ransomware families. Hancitor email application (SMTP, POP3, IMAP) sessions in the Netherlands delivered variants in sufficient volume to register as some of the top malware seen over the period. The Netherlands had more Hancitor samples and sessions compared with the next country, Sweden. In the Netherlands High Tech was the highest affected industry by Hancitor compared to Sweden’s Professional and Legal industries; the next most affected industry in both countries was Manufacturing. Globally, at the time, the number one industry affected by Hancitor was Healthcare.

with fairly high session volume in each country though not as sustained or consistent as the aforementioned ransomware families. Hancitor email application (SMTP, POP3, IMAP) sessions in the Netherlands delivered variants in sufficient volume to register as some of the top malware seen over the period. The Netherlands had more Hancitor samples and sessions compared with the next country, Sweden. In the Netherlands High Tech was the highest affected industry by Hancitor compared to Sweden’s Professional and Legal industries; the next most affected industry in both countries was Manufacturing. Globally, at the time, the number one industry affected by Hancitor was Healthcare.

GhostPush is a malicious adware family that quickly spread worldwide allowing for complete takeover of an Android user’s device using novel techniques to maintain persistence and obfuscate its activity, including installing system level services, modifying the recovery script executed on device boot, and tricking the user into enabling automatic app installation.

During this time period, and in these four countries, we only saw the malicious adware in Sweden but, beyond these four countries there has been some consistent ![]() activity and, given some of the recently volume seen, the indications are that GhostPush is on the rise generally. In all the cases during this period GhostPush was also seen in conjunction with an Android advertisement library, UmengAdware, which is capable of displaying advertisements via the system notification bar, sending device GPS and other phone information, lists of installed (and currently running) applications and network operator details to a remote host. Furthermore, additional apps can be installed via this library as well.

activity and, given some of the recently volume seen, the indications are that GhostPush is on the rise generally. In all the cases during this period GhostPush was also seen in conjunction with an Android advertisement library, UmengAdware, which is capable of displaying advertisements via the system notification bar, sending device GPS and other phone information, lists of installed (and currently running) applications and network operator details to a remote host. Furthermore, additional apps can be installed via this library as well.

Atmos is a polymorphic variant of Citadel (that is based on ZeuS) that functions similarly, targeting financial and confidential user data. During this time period, we saw Atmos most in Denmark. Globally this malware has seen a recent decline after a ![]() period of heightened activity and, as with most malware, is delivered using email as part of malspam campaigns often purporting to be related to purchase orders with leading subject lines “Orders” and “Shipping information” with attachment filenames “ORDERnnnnnnnnnnn” where n is an 11-digit random number. The file itself is always an executable (EXE) however sometimes the extensions used can include other forms of executable file types, such as .PIF, .SCR and even.SCR.GZ as well as the more traditional .EXE.

period of heightened activity and, as with most malware, is delivered using email as part of malspam campaigns often purporting to be related to purchase orders with leading subject lines “Orders” and “Shipping information” with attachment filenames “ORDERnnnnnnnnnnn” where n is an 11-digit random number. The file itself is always an executable (EXE) however sometimes the extensions used can include other forms of executable file types, such as .PIF, .SCR and even.SCR.GZ as well as the more traditional .EXE.

Another malware we saw using very similar social engineering techniques to lure victims into opening attachments during this period in The Netherlands, Sweden, and Belgium but not Denmark but is LuminostyLink, a fully featured Remote Access Trojan (RAT) with very aggressive keylogger that injects its code in almost every running process on the computer. Always using .EXE for its attached file’s extension but on occasion using a second extension .GZ to make the file look like a GZIP compressed archive we saw LuminosityLink downloading additional payloads, such as Pony and Zeus – other Trojans capable of yet further downloads but also of stealing credentials and harvesting victim user and system information.

We’ve seen LuminosityLink fairly consistently ![]() over the past months with a small uptick of late. During this time period attacks using LuminosityLink and related malware relied purely on social engineering. This is in contrast with previous variants that try to automatically install themselves by attacking software vulnerabilities on the victim’s system; in some cases, targeting vulnerabilities dating back to 2012.

over the past months with a small uptick of late. During this time period attacks using LuminosityLink and related malware relied purely on social engineering. This is in contrast with previous variants that try to automatically install themselves by attacking software vulnerabilities on the victim’s system; in some cases, targeting vulnerabilities dating back to 2012.

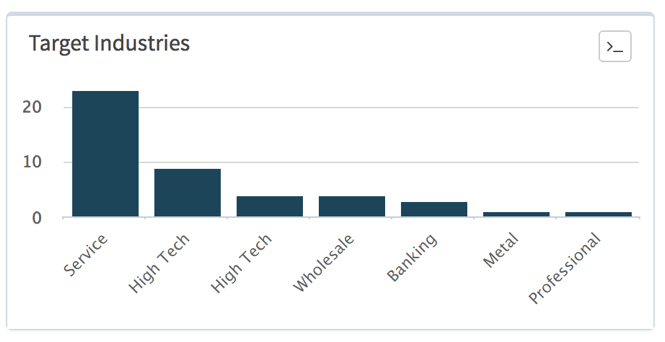

Figure 3 below shows during this period that in in The Netherlands, Sweden, and Belgium the Service Provider sector was the most targeted by LuminosityLink. We saw only two unique variants of LuminosityLink when searching AutoFocus using this search criterion and both variants were seen in 23 SMTP sessions where the emails claimed to be purchase order related, with subject line “FW: REQUEST FOR QUOTATION” and file attachment name “PO 010617.exe”. One of these two samples has also been tagged in AutoFocus as being part of the SilverTerrier campaign meaning that the sample was likely hosted on, or would talk-back during execution to a host that has been identified as being part of this campaign. For more information about SilverTerrier please refer to a whitepaper published late last year on the subject.

Figure 3 LuminosityLink by industry sector

Italy, Spain, and Switzerland

Italy and Spain, together with some other countries, are informally thought as being part of Southern Europe. Switzerland shares its southern border with northern Italy, and Italian is one of its official languages with between 5 and 10% of Swiss claiming it as their first language. All three countries, Italy, Spain, and Switzerland have a mixture of economic sectors including manufacturing, finance, agriculture and more. Italy is fourth, behind Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, in terms of population at approximately 60 million compared to Spain with approximately 46 million and Switzerland with approximately 8 million. Switzerland is the only country of the three that is neither a member of the European Union nor NATO.

In Italy, we saw a large volume of malicious sessions over email-based applications supplying KINS malware. The emails often purport to be documentation or user guide related, primarily in English, and almost always have double extensions, such as .pdf.exe or .eml.exe masquerading as PDF document or email files respectively. KINS malware is related to ZeusVM – a relatively new addition to the Zeus family of malware – and like other Zeus variants, it is a banking Trojan focusing on stealing user credentials from financial institutions.

Over this period in Italy, the majority of KINS volume ![]() targeted the High-Tech sector, followed by Professional and Legal services, Insurance, and Wholesale.

targeted the High-Tech sector, followed by Professional and Legal services, Insurance, and Wholesale.

Some of the KINS variants also downloaded Pony malware, which itself can download further payloads but also has credential harvesting capabilities too. We also saw Pony malware in Spain and Switzerland over this period. But we saw seeing the vast majority of Pony samples and sessions in Italy and Spain; globally Pony malware is always![]() fairly consistent and of late has been trending upwards slightly. Many of the Pony variants seen in Italy and Spain have been linked to other malware families including NanoCoreRAT (a Remote Access Trojan) and Neutrino, a point-of-sale malware which attempts to scrape credit card information from memory on the infected system. The malware often uses HTTP to request commands from the attacker.

fairly consistent and of late has been trending upwards slightly. Many of the Pony variants seen in Italy and Spain have been linked to other malware families including NanoCoreRAT (a Remote Access Trojan) and Neutrino, a point-of-sale malware which attempts to scrape credit card information from memory on the infected system. The malware often uses HTTP to request commands from the attacker.

In Spain, we saw High Tech and Higher Education sectors affected by variants of MacKeeper malware that purports to be a security product for Mac but actually serves ads to the victim. All the sessions that delivered MacKeeper in Spain used web-browsing application with downloaded filenames having .PKG extensions. ![]() Globally MacKeeper has been trending downwards recently.

Globally MacKeeper has been trending downwards recently.

All three countries saw large amounts of Locky and Cerber ransomware just as the other four countries listed above did, however, when you compare Switzerland’s lower volume of all malicious sessions over this period, the ratio of Locky malware present compared to Italy and Spain’s equivalent ratio is staggering. Almost half of the total unique samples and over half of the sessions seen in Switzerland during this period were Locky ransomware.

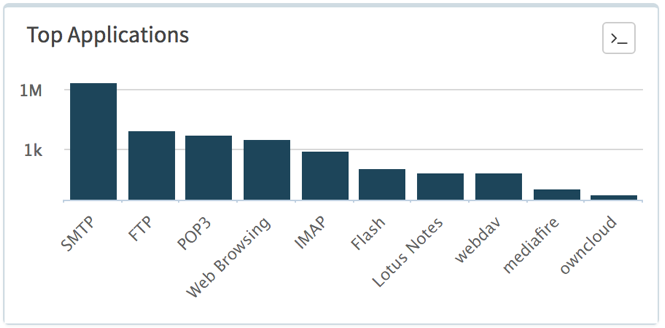

Generally speaking, the FTP (File Transfer Protocol) application does not register high in AutoFocus’ list of top applications carrying malware, let alone being above some email-based applications and web-browsing, but during this period such malicious activity spiked, as shown in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4 FTP high in the charts compared to normal

The vast majority of the FTP sessions we saw were in Spain, followed by Italy and finally Switzerland; the malware mostly responsible for this is Photominer, which is often seen with other malware such as CoinMiner. Both malwares have similar, fairly consistent![]() volumes throughout this period averaging over 2000 sessions per day and ranging from several hundreds some days to over 10,000 on other.

volumes throughout this period averaging over 2000 sessions per day and ranging from several hundreds some days to over 10,000 on other.

Photominer features a unique infection mechanism reaching users on their endpoints by infecting websites hosted on insecure FTP servers, which the victims browse to. Infection of an endpoint includes a component for mining crypto-currency (CoinMiner) as well as Photominer itself, which tries to find and compromise yet more FTP servers thus spreading the malware further.

Monero is the crypto currency of choice for this malware and its believes that the choice of a lesser known currency with a good exchange rate allows the attackers to rapidly gain money while the sophisticated use of safeguards makes it resilient to most disruption attempts.

Conclusion

EMEA is a socially and economically diverse region with many interesting assets whether they be citizen data, financial information, or natural resources and, as such, is a target for cyber criminals the world over.

It’s probably no surprise to see ransomware as a prevalent malware crossing all borders into all countries as this malware is really victim-agnostic. Any data on any computer in any country is a viable target.

Clearly information-stealing malware, such as KINS and Pony, are prevalent in countries that have a more service-based economy that manage and process plenty of user data and personally identifiable information (PII). While other countries more reliant on industrial sectors and natural resources seem to have more cyberattacks that make use of RATs providing full control to remote attackers and use of key-logging technologies to harvest data.

Cyber Hygiene

The threat landscape is vast and can be complex but you can minimize your risk of infection and enhance the overall health of your network by following some basic cyber hygiene habits:

Patch systems and applications wherever (and as soon as) possible. Alternatively, focus on other security solutions, such as exploit prevention technology to protect those systems and applications from attack or to help manage patching cycles to suit your requirements. Prioritize patching based on known exploits or in-the-wild-attacks. Segment those unpatched/unpatchable devices in the network with additional access controls based on users or application communication to minimize the risk of exploitation. Perform regular vulnerability scans of systems and review changes to spot new devices or changes in active vulnerabilities.

Change the file association for JavaScript to be opened using notepad (or something else benign) rather than the Windows Scripting Host or other shell capable of executing malcode. This can be done per PC or enterprise-wide using Group Policy.

Educate users and employees of the security risks faced by your organization and perform regular training and reminders about these and how they can help the effort. Provide a platform for users to learn about the risks and to report incidents to security-related staff. Create a culture whereby such reporting is important and valued. Monitor effectiveness of training for the purposes of gap analysis and creating dialogue between security teams and users.

Ignite ’17 Security Conference: Vancouver, BC June 12–15, 2017

Ignite ’17 Security Conference is a live, four-day conference designed for today’s security professionals. Hear from innovators and experts, gain real-world skills through hands-on sessions and interactive workshops, and find out how breach prevention is changing the security industry. Visit the Ignite website for more information on tracks, workshops and marquee sessions.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42