Unit 42 has identified malware with recent compilation and distribution timestamps that has code, infrastructure, and themes overlapping with threats described previously in the Operation Blockbuster report, written by researchers at Novetta. This report details the activities from a group they named Lazarus, their tools, and the techniques they use to infiltrate computer networks. The Lazarus group is tied to the 2014 attack on Sony Pictures Entertainment and the 2013 DarkSeoul attacks.

This recently identified activity is targeting Korean speaking individuals, while the threat actors behind the attack likely speak both Korean and English. This blog will detail the recently discovered samples, their functionality, and their ties to the threat group behind Operation Blockbuster.

Initial Discovery and Delivery

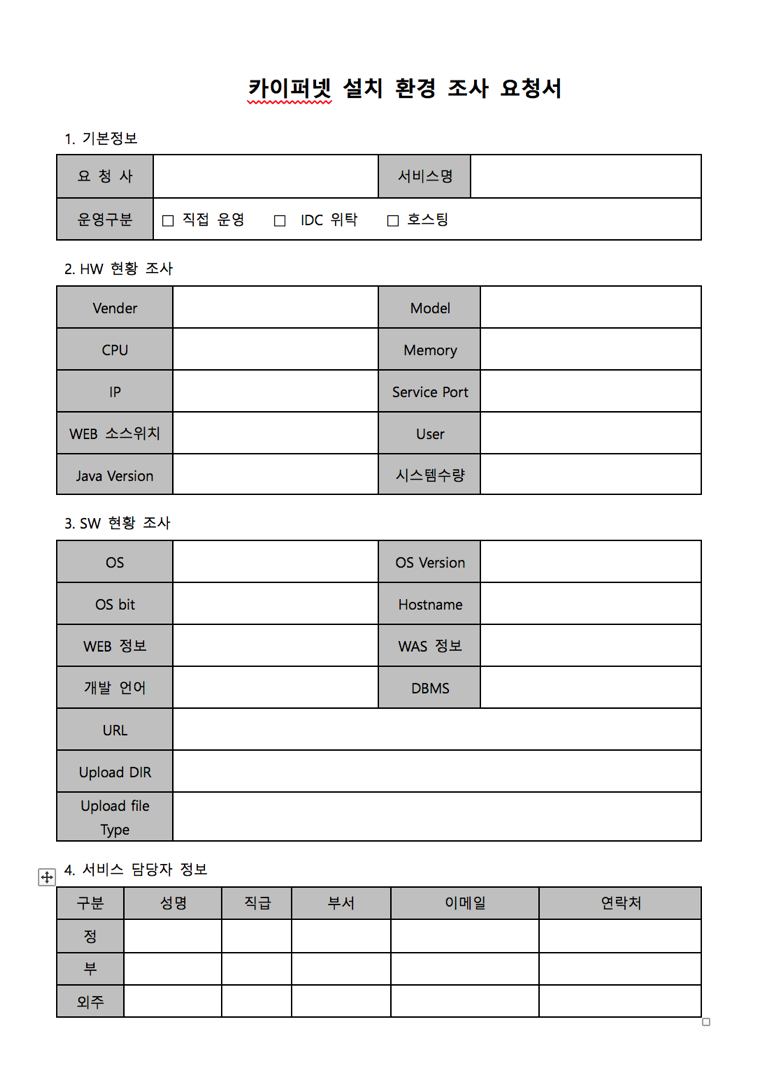

This investigation began when we identified two malicious Word document files in AutoFocus threat intelligence tool. While we cannot be certain how the documents were sent to the targets, phishing emails are highly likely. One of the malicious files was submitted to VirusTotal on 6 March 2017 with the file name "한싹시스템.doc". Once opened, both files display the same Korean language decoy document which appears to be the benign file located online at "www.kuipernet.co.kr/sub/kuipernet-setup.docx".

Figure 1 Dropped decoy document

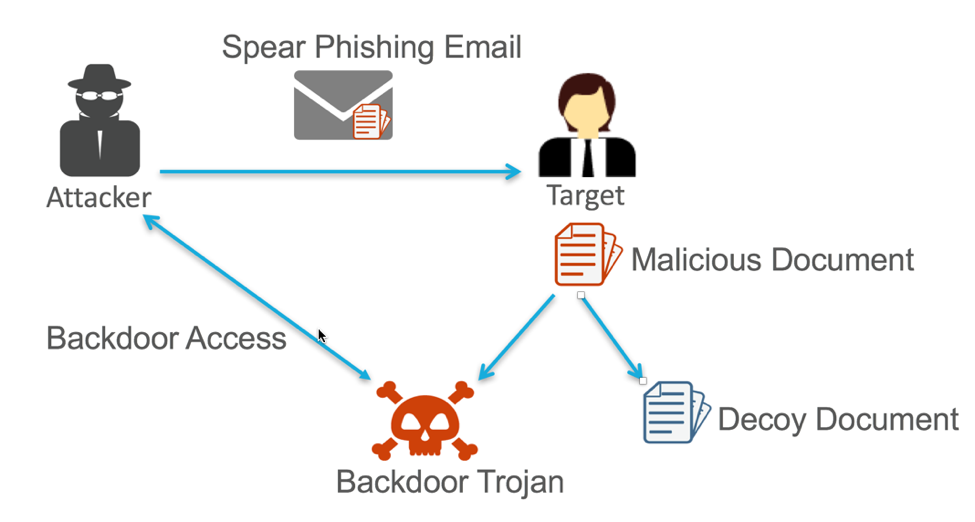

This file (Figure 1) appears to be a request form used by the organization. Decoy documents are used by attackers who want to trick victims into thinking a received file is legitimate. At the moment, the malware infects the computer, it opens a non-malicious file that contains content the target expected to receive (Figure 2.) This serves to fool the victim into thinking nothing suspicious has occurred.

Figure 2 Spear Phishing Attack uses a decoy a file to trick the target

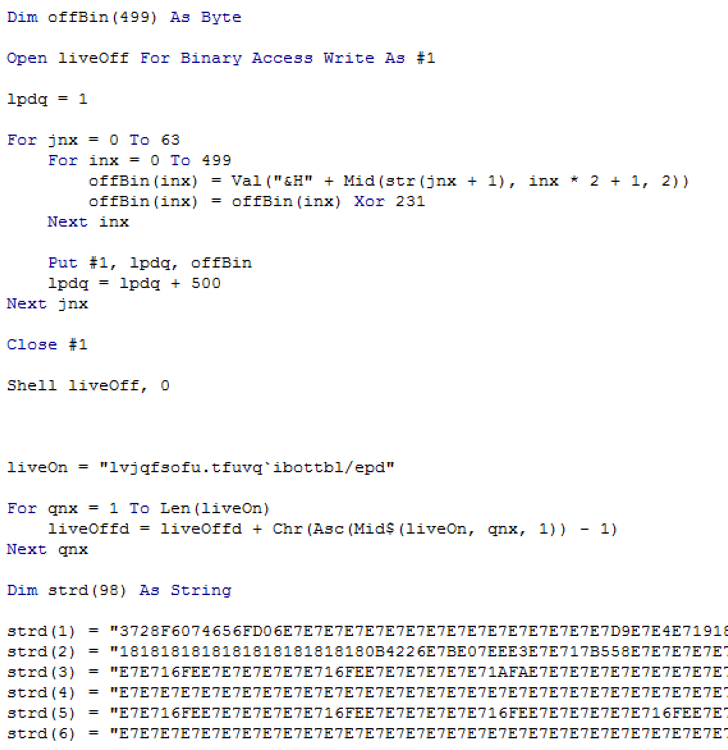

When these malicious files are opened by a victim, malicious Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) macros within them write an executable to disk and run it. If macros are disabled in Microsoft Word, the user must click the “Enable Content” button for malicious VBA script to execute. Both documents make use of logic and variable names within their macros, which are very similar to each other. Specifically, they both contain strings of hex that when reassembled and XOR-decoded reveal a PE file. The PE file is written to disk with a filename that is encoded in the macro using character substitution. Figure 3 shows part of the logic within the macros which is identical in both files.

Figure 3 Malicious document malicious macro source code

The Embedded Payload

The executable which is dropped by both malicious documents is packed with UPX. Once unpacked, the payload (032ccd6ae0a6e49ac93b7bd10c7d249f853fff3f5771a1fe3797f733f09db5a0) can be statically examined. The compile timestamp of the sample is March 2nd, 2017, just a few days before one of the documents carrying the implant was submitted to VirusTotal.

The payload ensures a copy of itself is located on disk within the %TEMP% directory and creates the following registry entry to maintain persistence if the system is shutdown

|

1 2 |

HKLM\SOFTWARE\Wow6432Node\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\JavaUpdate , Value:%TEMP%\java.exe /c /s |

It then executes itself with the following command line:

|

1 |

%TEMP%\java.exe /c %TEMP%\java.exe |

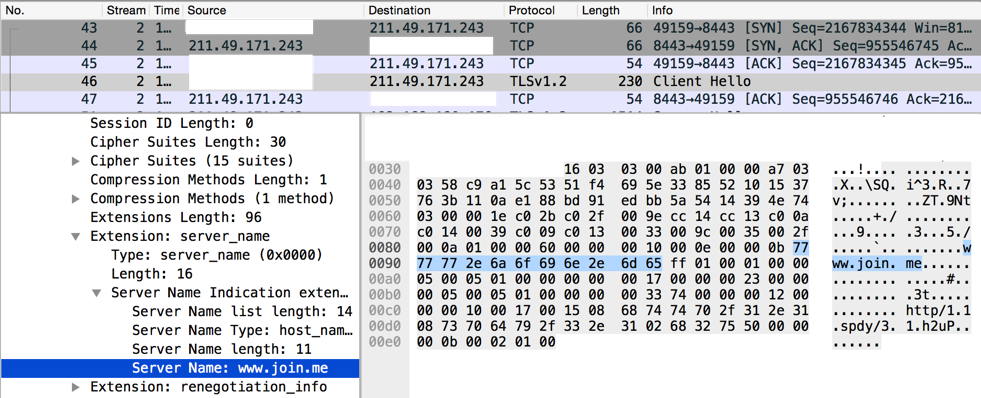

The implant beacons to its command and control (C2) servers directly via the servers' IPv4 addresses, which are hard coded in the binary, no domain name is used to locate the servers. The communications between the implant and the server highly resemble the "fake TLS" protocol associated with malware tools used by the Lazarus group and described in the Operation Blockbuster report. However, the possible values of the Server Name Indication (SNI) record within the CLIENT HELLO of the TLS handshake used by the implant differ from those described in the report. The names embedded in the new sample and chosen for communications include:

- twitter.com

- www.amazon.com

- www.apple.com

- www.bing.com

- www.facebook.com

- www.microsoft.com

- www.yahoo.com

- www.join.me

The C2 servers contacted by the implant mimic the expected TLS server responses from the requested SNI field domain name, including certificate fields such as the issuer and subject. However, the certificates' validity, serial number, and fingerprint are different. Figure 4 shows a fake TLS session which includes the SNI record "www.join.me" destined for an IPv4 address which does not belong to Join.Me.

Figure 4 The use of "www.join.me" as an SNI record of a TLS handshake to an IPv4 address which does not host that domain name

Expanding the Analysis

Because the attackers reused similar logic and variable names in their macros, we were able to locate additional malicious document samples. Due to the heavy reuse of code in the macros we also speculate the documents are created using an automated process or script. Our analysis of the additional malicious documents showed some common traits across the documents used by the attackers:

- Many, but not all, of the documents have the same author

- Malicious documents support the ability to drop a payload as well as an optional decoy document

- XOR keys used to encode embedded files within the macros seem to be configurable

- All of the dropped payloads were compressed with a packer (the packer used varied)

Multiple testing documents which dropped and executed the Korean version of the Microsoft calc.exe executable, but contained no malicious code, were also identified. This mirrors a common practice in demonstrating exploits of vulnerabilities. Interestingly enough, all of the test documents identified were submitted to VirusTotal with English file names from submitters located in the United States (although not during US "working hours"). Despite the documents having Korean code pages, when executed they open decoy documents with the English text: "testteststeawetwetwqetqwetqwetqw". These facts lead us to believe at least some of the developers or testers of the document weaponizing tool may be English speakers.

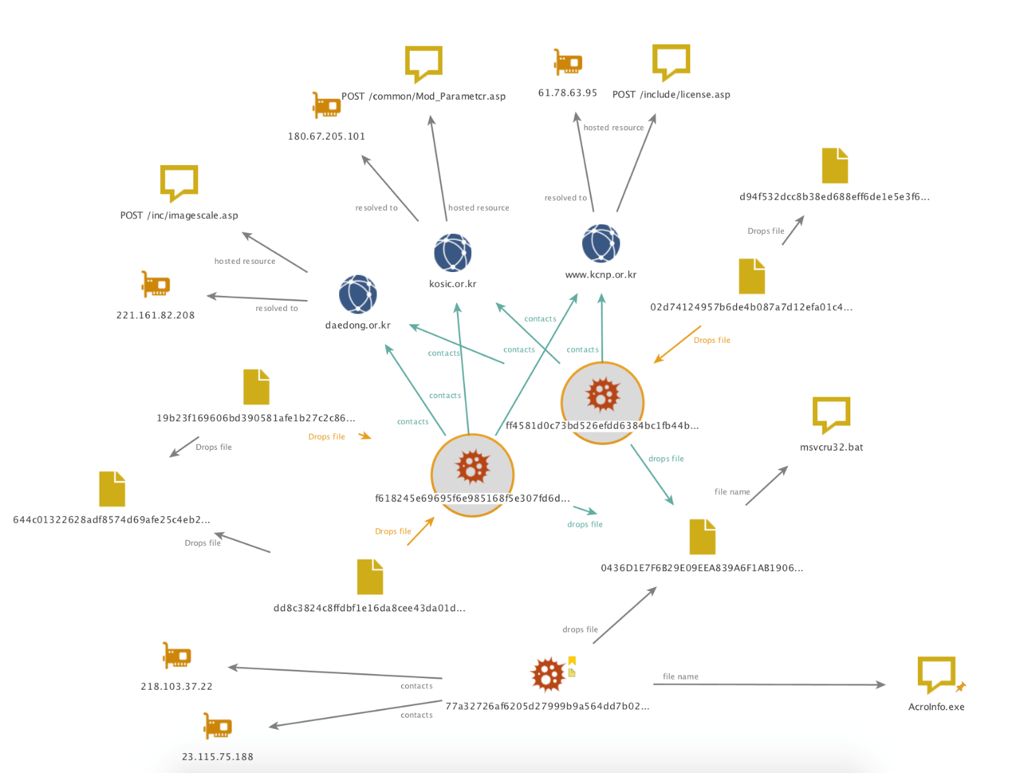

While some of the documents identified carry benign payloads, most of the payloads were found to be malicious. A cluster of three malicious documents were identified that drop payloads which are related via C2 domains. The payloads can be seen highlighted in Figure 5.

Figure 5 Related executables, their C2 domain names, their dropper documents, and the shared batch file

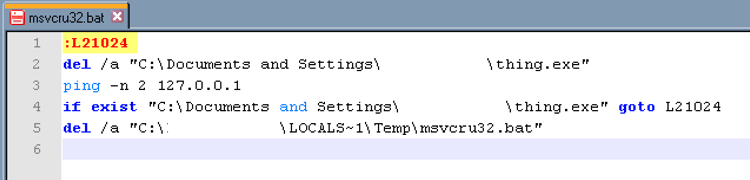

The two malicious payloads circled in Figure 5 write a batch script to disk that is used for deleting the sample and itself, which is a common practice. The batch script dropped by the two payloads share a file name, file path, and hash value with a script sample (77a32726af6205d27999b9a564dd7b020dc0a8f697a81a8f597b971140e28976). This sample is described in a 2016 research report by Blue Coat discussing connections between the DarkSeoul group and the Sony breach of 2014.

The script's (Figure 6) hash value will vary depending on the name of the file it is to delete. It also includes an uncommon label inside it of "L21024". The file the script deletes is the payload which writes the script to disk. In the case of Figure 6, the payload was named "thing.exe".

Figure 6 The contents of the shared batch script

Ties to Previous Attacks

In addition to the commonalities already identified in the communication protocols and the shared cleanup batch script use by implants, the payloads also share code similarities with samples detailed in Operation Blockbuster. This is demonstrated by analyzing the following three samples, which behave in similar ways:

032ccd6ae0a6e49ac93b7bd10c7d249f853fff3f5771a1fe3797f733f09db5a0

79fe6576d0a26bd41f1f3a3a7bfeff6b5b7c867d624b004b21fadfdd49e6cb18 520778a12e34808bd5cf7b3bdf7ce491781654b240d315a3a4d7eff50341fb18

We used these three samples to reach the conclusion that the samples investigated are tied to the Lazarus group.

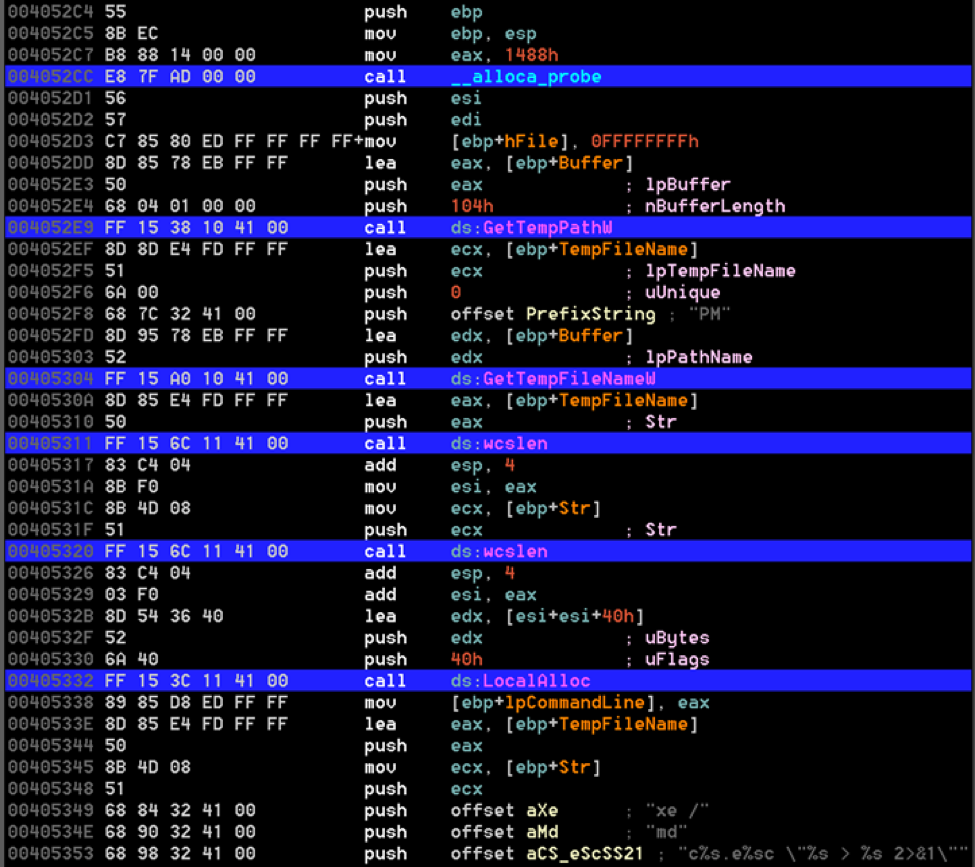

First, these three samples all use a unique method of executing a shell command on the system. An assembly function is passed four strings. Some of the strings contain placeholders. The function interpolates the strings and creates a system command to be executed. The following four parameters are passed to the function:

- "PM",

- "xe /"

- "md"

- "c%s.e%sc \ "%s > %s 2>&1\"

These are used not only in the implant we investigated, but also in the two samples above. Additionally, many samples discussed in the Operation Blockbuster report also made use of this technique. Figure 7 shows the assembly from the unpacked implant (032ccd6ae0a6e49ac93b7bd10c7d249f853fff3f5771a1fe3797f733f09db5a0) delivered by our malicious document and shows the string interpolation function being used.

Figure 7 The string interpolation function assembly with library names from 032ccd6ae0a6e49ac93b7bd10c7d249f853fff3f5771a1fe3797f733f09db5a0

Figure 8 shows the same string interpolation logic but within a different sample (79fe6576d0a26bd41f1f3a3a7bfeff6b5b7c867d624b004b21fadfdd49e6cb18.) The instructions are the same except where the system calls are replaced with DWORDs which brings us to a second similarity.

Figure 8 The string interpolation function assembly without library names from 79fe6576d0a26bd41f1f3a3a7bfeff6b5b7c867d624b004b21fadfdd49e6cb18

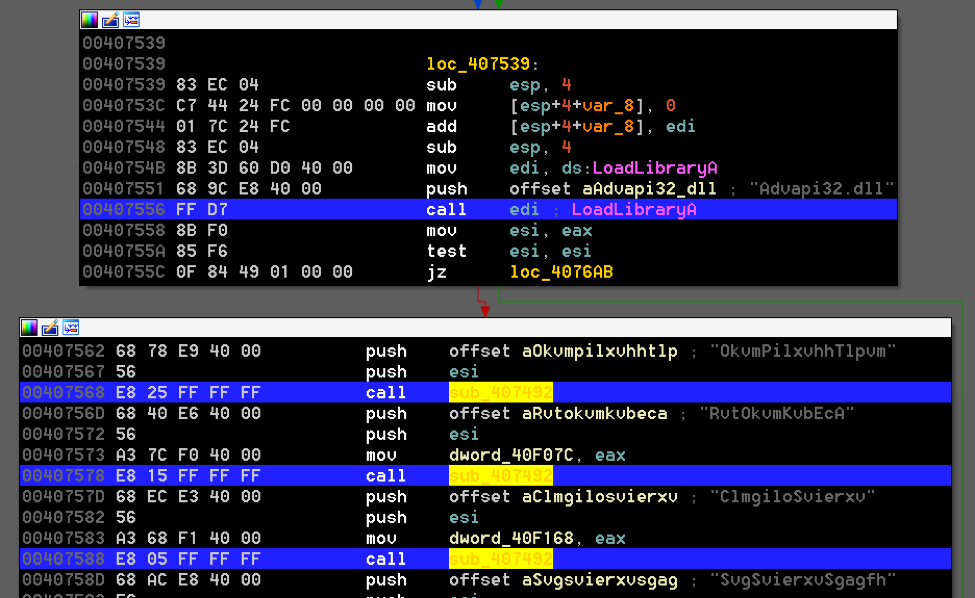

The second similarity ties this sample to a known Lazarus group sample (520778a12e34808bd5cf7b3bdf7ce491781654b240d315a3a4d7eff50341fb18.) Upon execution, both samples set aside memory to be used as function pointers. These pointers are assigned values by a dedicated function in the binary. Other functions in the binary call the function pointers instead of the system libraries directly. The motivation for the use of this indirection is unclear, however, it provides an identifying detection mechanism.

These two samples resolve system library functions in a similar yet slightly different manner. The sample known to belong to the Lazarus group uses this indirect library calling in addition to a function that further obfuscates the function's names using a lookup table within a character substitution function. This character substitution aspect was removed in the newer samples. The purpose for removing this functionality between the original Operation Blockbuster report samples and these newer ones is unclear. Figure 9 displays how this character substitution function was called within the Lazarus group sample.

Figure 9 The character substitution function from 520778a12e34808bd5cf7b3bdf7ce491781654b240d315a3a4d7eff50341fb18 being called

| SHA256 Hash | String Interpolation Function | System Library Obfuscation | Fake TLS Communications | Label |

| 032ccd6ae0a6e49ac93b7bd10c7d249f853fff3f5771a1fe3797f733f09db5a0 | Yes | No | Yes | Initially identified payload |

| 79fe6576d0a26bd41f1f3a3a7bfeff6b5b7c867d624b004b21fadfdd49e6cb18 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Sample identified to be related to initial payload and Operation Blockbuster sample |

| 520778a12e34808bd5cf7b3bdf7ce491781654b240d315a3a4d7eff50341fb18 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Known Operation Blockbuster sample |

Figure 10: A comparison of features between samples

Final Thought

Overlaps in network protocols, library name obfuscation, process creation string interpolation, and dropped batch file contents demonstrate a clear connection between the recent activity Unit 42 has identified and previously reported threat campaigns. Demonstrated by the malicious document contents, the targets of this new activity are likely Korean speakers, while the attackers are likely English and Korean speakers.

It is unlikely these threat actors will stop attacking their targets. Given the slight changes that have occurred within samples between reports, it is likely this group will continue to develop their tools and skillsets.

Customers using WildFire are protected from these threats and customers using AutoFocus can find samples from this campaign tagged as Blockbuster Sequel.

Indicators of Compromise

Initial Malicious Documents

cec26d8629c5f223a120677a5c7fbd8d477f9a1b963f19d3f1195a7f94bc194b

ff58189452668d8c2829a0e9ba8a98a34482c4f2c5c363dc0671700ba58b7bee

Initial Payload

1322b5642e19586383e663613188b0cead91f30a0ab1004bf06f10d8b15daf65

032ccd6ae0a6e49ac93b7bd10c7d249f853fff3f5771a1fe3797f733f09db5a0 (unpacked)

Testing Malicious Documents

90e74b5d762fa00fff851d2f3fad8dc3266bfca81d307eeb749cce66a7dcf3e1

09fc4219169ce7aac5e408c7f5c7bfde10df6e48868d7b470dc7ce41ee360723

d1e4d51024b0e25cfac56b1268e1de2f98f86225bbad913345806ff089508080

040d20357cbb9e950a3dd0b0e5c3260b96b7d3a9dfe15ad3331c98835caa8c63

dfc420190ef535cbabf63436e905954d6d3a9ddb65e57665ae8e99fa3e767316

f21290968b51b11516e7a86e301148e3b4af7bc2a8b3afe36bc5021086d1fab2

1491896d42eb975400958b2c575522d2d73ffa3eb8bdd3eb5af1c666a66aeb08

31e8a920822ee2a273eb91ec59f5e93ac024d3d7ee794fa6e0e68137734e0443

49ecead98ebc750cf0e1c48fccf5c4b07fadef653be034cdcdcd7ba654f713af

5c10b34e99b0f0681f79eaba39e3fe60e1a03ec43faf14b28850be80830722cb

600ddacdf16559135f6e581d41b30d0867aae313fbaf66eb4d18345b2136cdd7

6ccb8a10e253cddd8d4c4b85d19bbb288b56b8174a3f1f2fe1f9151732e1a7da

8b2c44c4b4dc3d7cf1b71bd6fcc37898dcd9573fcf3cb8159add6cb9cfc9651b

9e71d0fdb9874049f310a6ab118ba2559fc1c491ed93c3fd6f250c780e61b6ff

Additional Related Samples

02d74124957b6de4b087a7d12efa01c43558bf6bdaccef9926a022bcffcdcfea

0c5cdbf6f043780dc5fff4b7a977a1874457cc125b4d1da70808bfa720022477

18579d1cc9810ca0b5230e8671a16f9e65b9c9cdd268db6c3535940c30b12f9e

19b23f169606bd390581afe1b27c2c8659d736cbfa4c3e58ed83a287049522f6

1efffd64f2215e2b574b9f8892bbb3ab6e0f98cf0684e479f1a67f0f521ec0fe

440dd79e8e5906f0a73b80bf0dc58f186cb289b4edb9e5bc4922d4e197bce10c

446ce29f6df3ac2692773e0a9b2a973d0013e059543c858554ac8200ba1d09cf

557c63737bf6752eba32bd688eb046c174e53140950e0d91ea609e7f42c80062

5c10b34e99b0f0681f79eaba39e3fe60e1a03ec43faf14b28850be80830722cb

644c01322628adf8574d69afe25c4eb2cdc0bfa400e689645c2ab80becbacc33

6a34f4ce012e52f5f94c1a163111df8b1c5b96c8dc0836ba600c2da84059c6ad

77a32726af6205d27999b9a564dd7b020dc0a8f697a81a8f597b971140e28976

79fe6576d0a26bd41f1f3a3a7bfeff6b5b7c867d624b004b21fadfdd49e6cb18

8085dae410e54bc0e9f962edc92fa8245a8a65d27b0d06292739458ce59c6ba1

8b21e36aa81ace60c797ac8299c8a80f366cb0f3c703465a2b9a6dbf3e65861e

9c6a23e6662659b3dee96234e51f711dd493aaba93ce132111c56164ad02cf5e

d843f31a1fb62ee49939940bf5a998472a9f92b23336affa7bccfa836fe299f5

dcea917093643bc536191ff70013cb27a0519c07952fbf626b4cc5f3feee2212

dd8c3824c8ffdbf1e16da8cee43da01d43f91ee3cc90a38f50a6cc8d6a778b57

efa2a0bbb69e60337b783db326b62c820b81325d39fb4761c9b575668411e12c

f365a042fbf57ed2fe3fd75b588c46ae358c14441905df1446e67d348bd902bf

f618245e69695f6e985168f5e307fd6dc7e848832bf01c529818cbcfa4089e4a

fa45603334dae86cc72e356df9aa5e21151bb09ffabf86b8dbf5bf42bd2bbadf

fc19a42c423aefb5fdb19b50db52f84e1cbd20af6530e7c7b39435c4c7248cc7

ff4581d0c73bd526efdd6384bc1fb44b856120bc6bbf0098a1fa0de3efff900d

C2 Domains

daedong.or[.]kr

kcnp.or[.]kr

kosic.or[.]kr

wstore[.]lt

xkclub[.]hk

C2 IPv4 Addresses

103.224.82[.]154

180.67.205[.]101

182.70.113[.]138

193.189.144[.]145

199.26.11[.]17

209.105.242[.]64

211.233.13[.]11

211.233.13[.]62

211.236.42[.]52

211.49.171[.]243

218.103.37[.]22

221.138.17[.]152

221.161.82[.]208

23.115.75[.]188

61.100.180[.]9

61.78.63[.]95

80.153.49[.]82

Ignite ’17 Security Conference: Vancouver, BC June 12–15, 2017

Ignite ’17 Security Conference is a live, four-day conference designed for today’s security professionals. Hear from innovators and experts, gain real-world skills through hands-on sessions and interactive workshops, and find out how breach prevention is changing the security industry. Visit the Ignite website for more information on tracks, workshops and marquee sessions.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42