Executive Summary

In April 2020, we reported on a large influx of COVID-19 themed phishing attacks starting in February 2020. With March 2021 marking the one-year anniversary that the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic, we revisited the phishing trends we observed in the past year to gain deeper insight into the various COVID-related topics that attackers might try to exploit.

Starting with the set of all phishing URLs detected globally between January 2020 and February 2021, we generated sets of specific keywords (or phrases) that served as indicators for each COVID-related topic, and applied keyword matching to determine which phishing URLs were related to each topic. (To ensure that the matched URLs were indeed COVID-related, we iteratively spot-checked the resulting URLs and refined these keywords/phrases to minimize the incidence of false positives.)

We found that at each step along the way, attackers have continued to change their chosen tactics to adapt to the latest pandemic trends, in hopes that maintaining a timely sense of urgency will make it more likely for victims to give up their credentials.

We found phishing attacks largely centered around Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and testing kits in March 2020, government stimulus programs from April through the summer 2020 (including a fake U.S. Trading Commission website that posed as the U.S. Federal Trade Commission in order to steal user credentials) and vaccines from late fall 2020 onward (including a fake Pfizer and BioNTech website also stealing user credentials). Of note, we found that vaccine-related phishing attacks rose by 530% from December 2020 to February 2021, and that phishing attacks relating to and/or targeting pharmacies and hospitals rose by 189% during that same timeframe.

We found no evidence that any of these efforts were successful, but are highlighting these cases to make healthcare organizations around the globe aware of this heightened activity targeting their sector, so they can alert employees to be on guard for malicious credential-phishing sites.

We predict that as the vaccine rollout continues, phishing attacks related to vaccine distribution – including attacks targeting the healthcare and life sciences industries – will continue to rise worldwide.

Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall customers are protected from phishing attacks with a variety of security services, including URL Filtering, DNS Security, Threat Prevention and GlobalProtect.

In addition to these security services, best practices to protect yourself and your organization from phishing attacks include:

For individuals:

- Exercising caution when clicking on any links or attachments contained in suspicious emails, especially those relating to one’s account settings or personal information, or otherwise trying to convey a sense of urgency.

- Verifying the sender address for any suspicious emails in your inbox.

- Double-checking the URL and security certificate of each website before inputting your login credentials.

- Reporting suspected phishing attempts.

For organizations:

- Implementing security awareness training to improve employees’ ability to identify fraudulent emails

- Regularly backing up your organization’s data as a defense against ransomware attacks initiated via phishing emails.

- Enforcing multi-factor authentication on all business-related logins as an added layer of security.

Phishing Trends

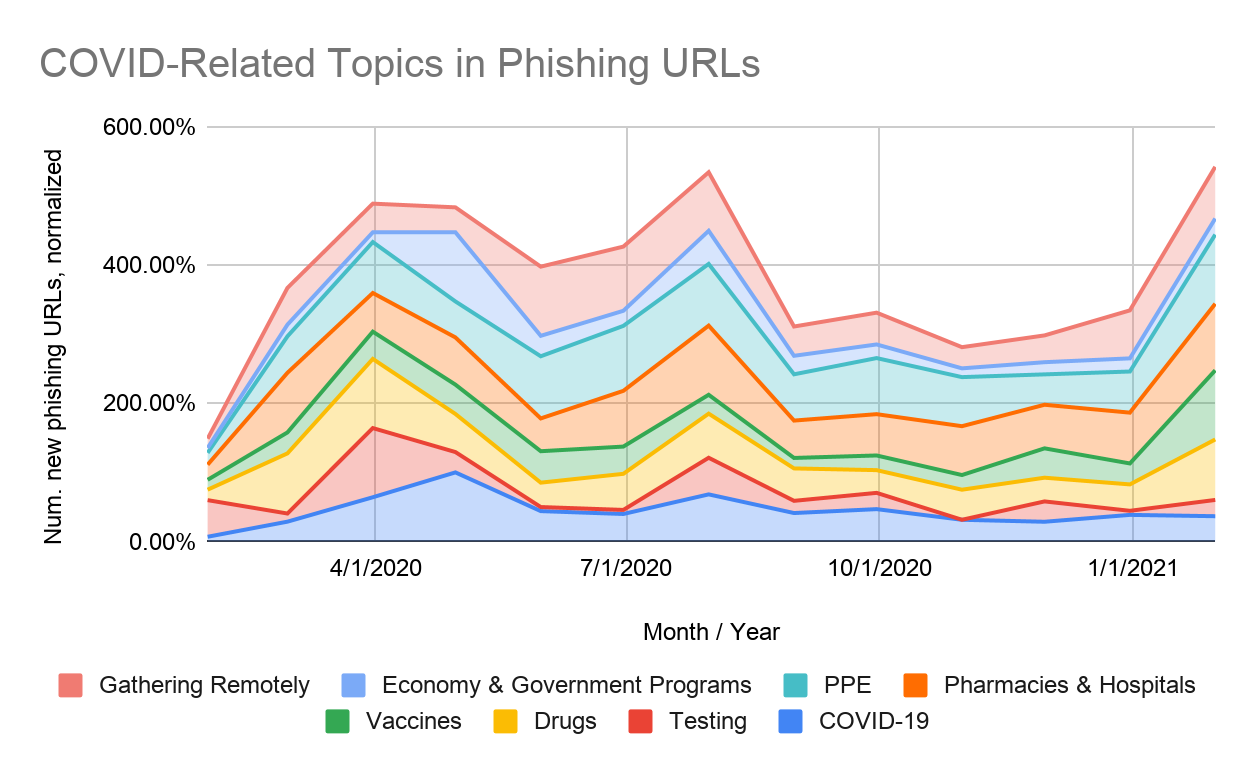

Since January 2020, we have observed 69,950 phishing URLs linked to COVID-related topics, of which 33,447 are directly linked to COVID-19 itself. In Figure 1, we plot the relative popularity of these different topics over time, normalized so that each topic has a peak popularity of 100%. Looking at how the heights of each colored section differs over time, we can see that certain topics have remained steady targets of phishing attacks, while others have experienced more noticeable spikes at various points in time. Pharmaceutical drugs and gathering virtually (e.g. Zoom), for example, have been a relatively steady target of phishing attacks since the start of the pandemic; vaccines and testing, on the other hand, have experienced more defined peaks in popularity.

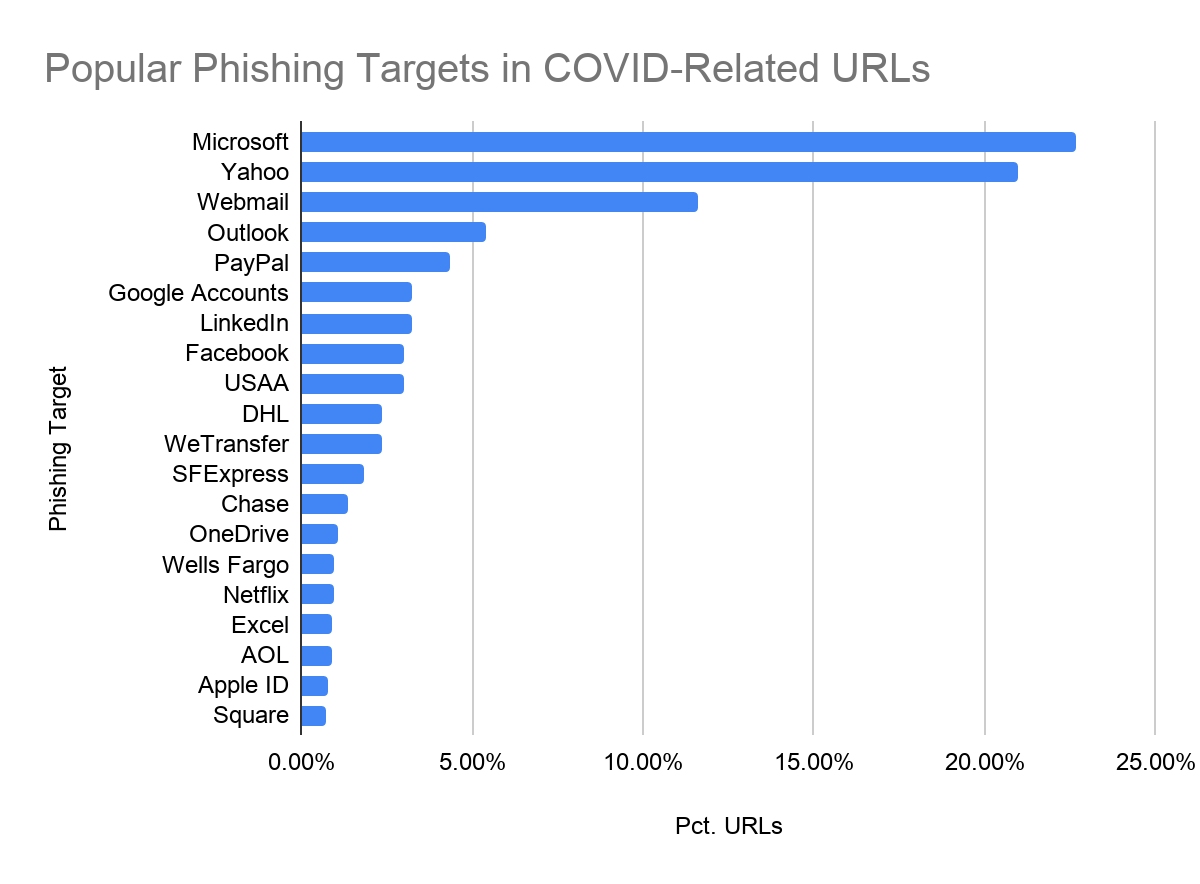

For the COVID-19 themed phishing pages that were found to be targeting known brands, we determined that the majority of these pages were attempting to steal users’ business credentials: e.g. Microsoft, Webmail, Outlook, etc. Each bar in Figure 2 represents the percentage of phishing URLs that were attempting to steal users’ login credentials for that particular website. (For example, about 23% of COVID-themed phishing URLs were fake Microsoft login pages.) With the pandemic forcing many employees to shift to remote work, these business-related phishing attempts have become an increasingly important attack vector for cybercriminals.

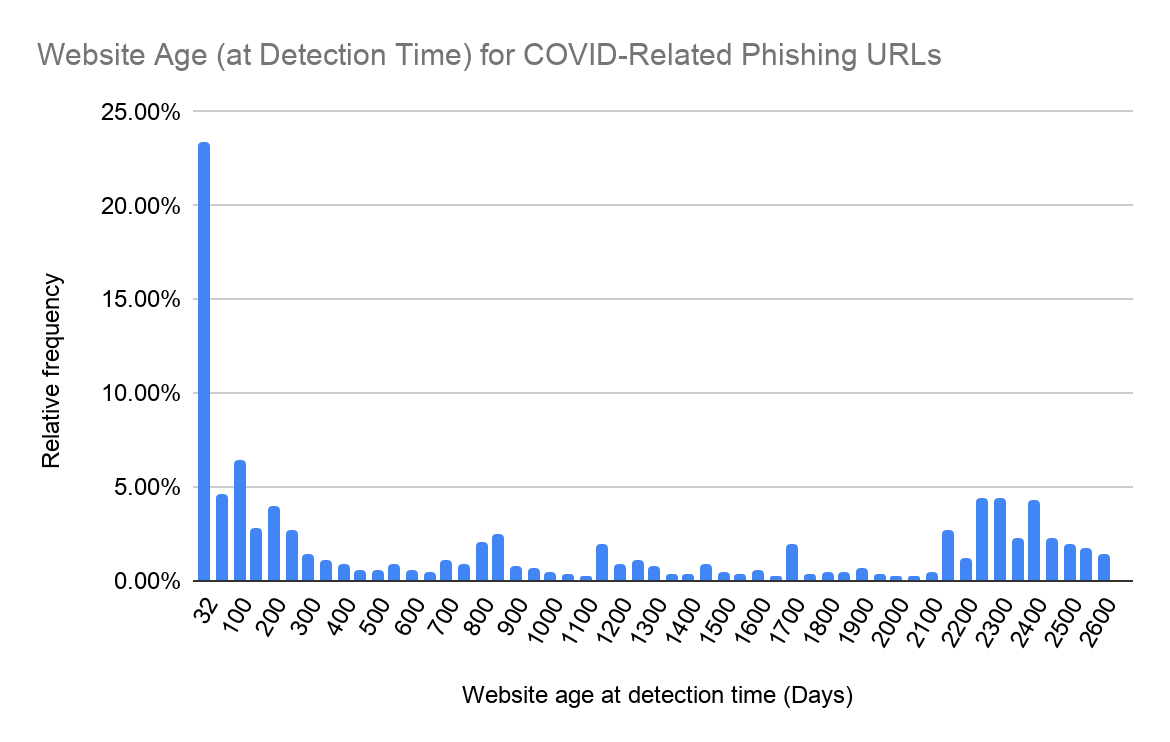

Furthermore, we notice that with these COVID-19 themed phishing attacks, attackers are constantly creating new websites to host their phishing campaigns. In Figure 3, which shows the age for each website that we found to host a COVID-related phishing page, we can see that many COVID-related phishing pages are hosted on newly created sites (we define this as sites that were first observed fewer than 32 days ago), suggesting that attackers purposefully set up these sites just days before their intended attacks. This gives the attackers the opportunity to craft the message surrounding the attack – as well as the website URL itself – to fit the latest pandemic trends.

January-March 2020: Initial Surge, Testing Kits and PPE

Between January and February 2020, as COVID-19 began its spread throughout the world, cybercriminals had already begun trying to use the soon-to-be pandemic to their advantage. During this timeframe, we observed a 313% increase in phishing attacks directly related to COVID-19.

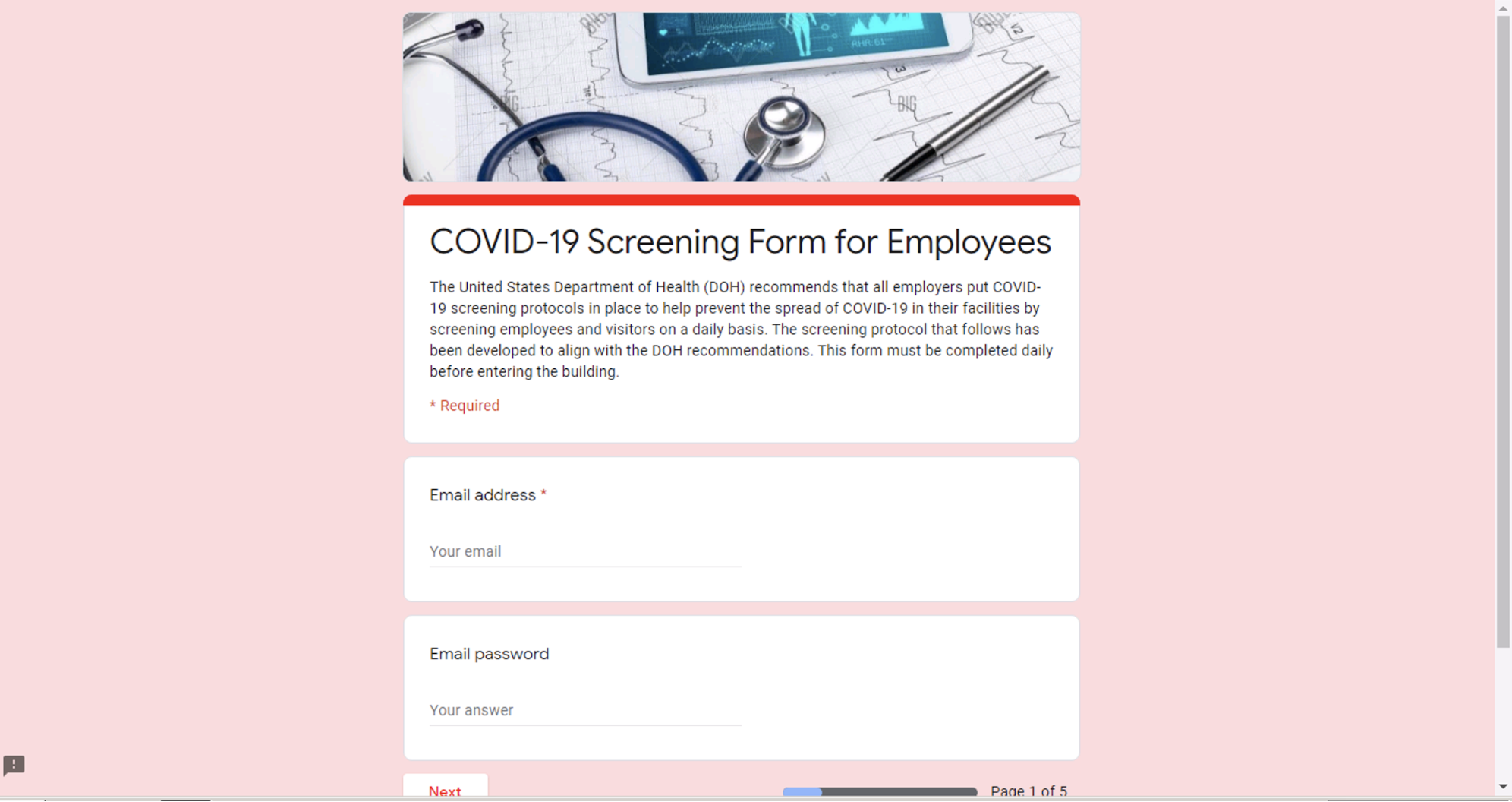

In Figure 4, we see an example of a COVID-19 themed phishing attack. The fake Google Form first asks the user to input his or her email address and password in order to participate in a supposed company COVID-19 screening program. In the subsequent pages, the form asks a series of legitimate-sounding health-related questions, e.g. “Since your last day of work, have you had two or more of the following? Chills, Repeated shaking with chills, Headache, Muscle pain, Sore throat, New loss of taste or smell,” to give the impression that the form itself is legitimate. The final question before submission asks the employee to “digitally sign” the form by entering his or her full name.

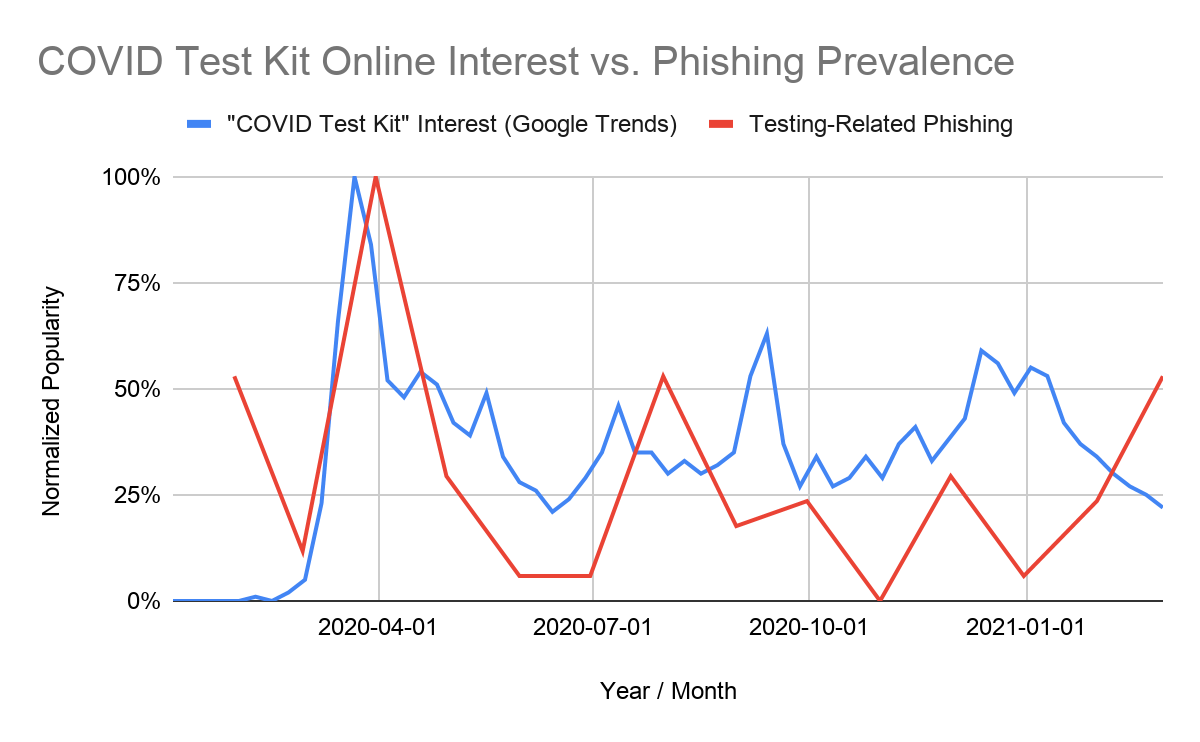

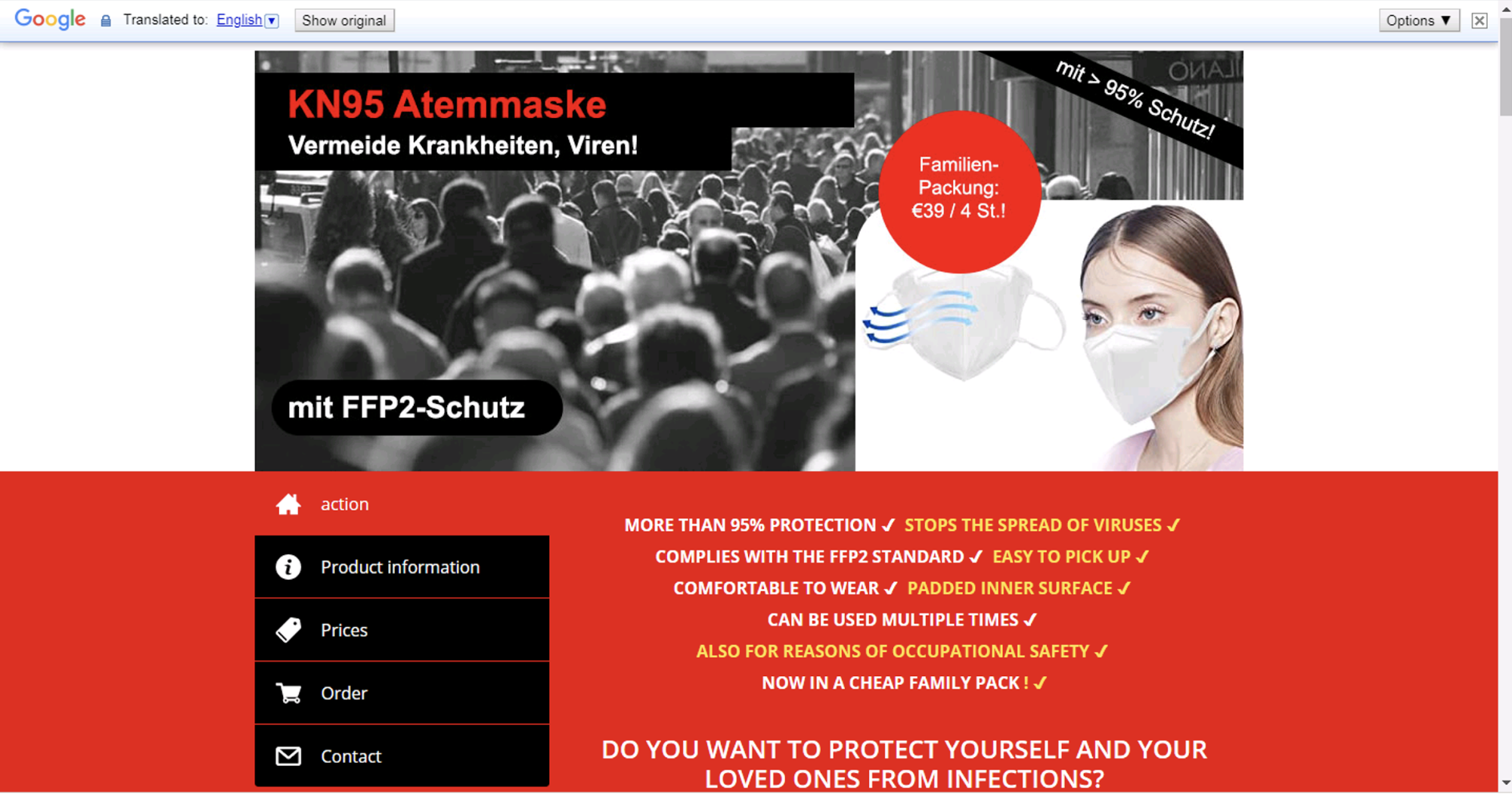

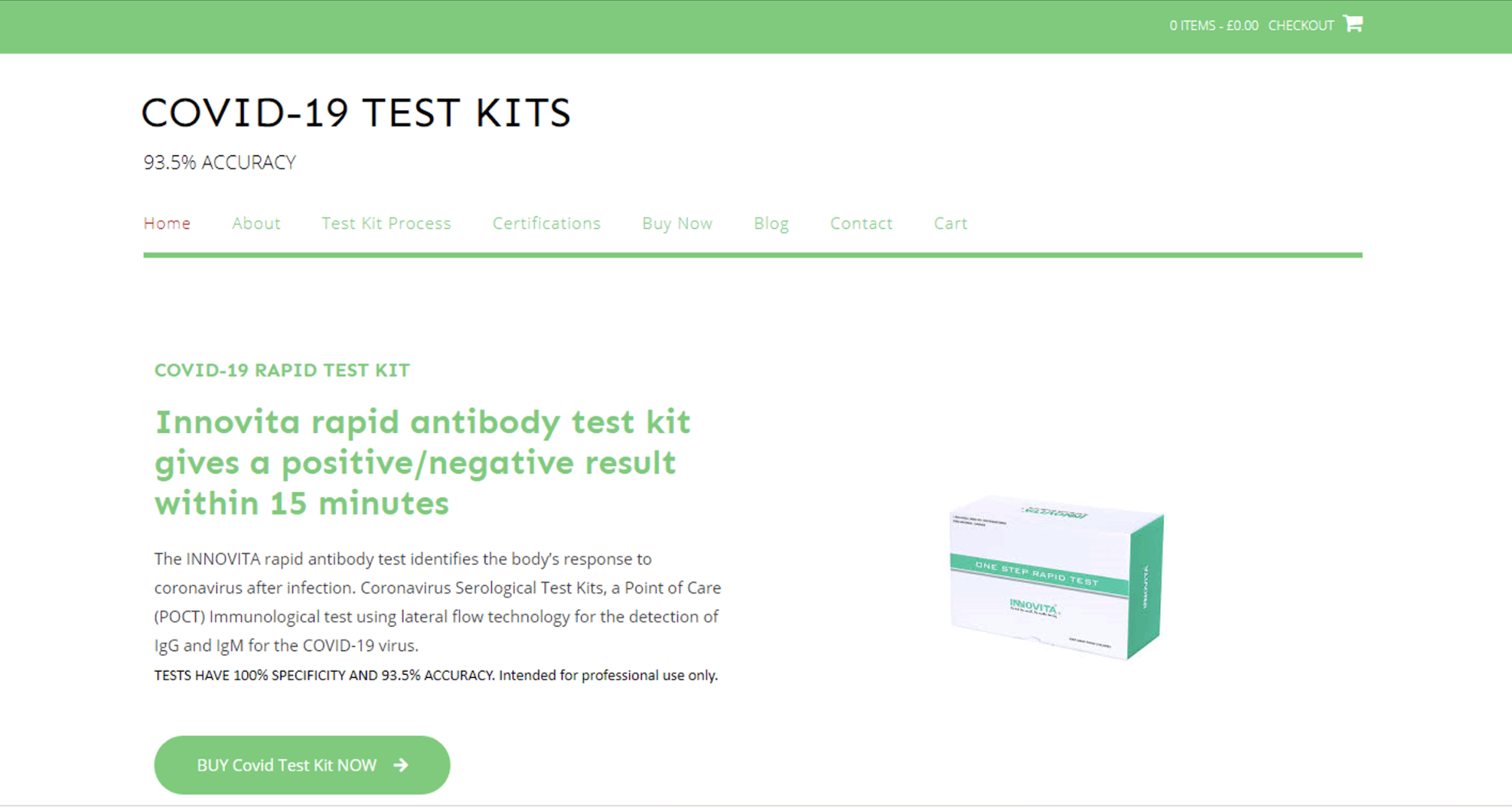

These trends are observable in our historical phishing data as well. In February 2020, we observed a 136% increase in PPE-related phishing attacks worldwide, many of which took the form of online shopping scams (see Figure 6 for an example). During the month of March, we observed a 750% increase in phishing attacks related to testing kits, just as The New York Times reported on a shortage of COVID tests across the U.S.

April-July 2020: Government Stimulus and Relief Programs

In April 2020, the IRS began distributing $1,200 stimulus checks to individuals as a part of the CARES Act. Around the same time, the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) was put into action, promising to provide relief to small businesses across the U.S. Many business owners scrambled to get a piece of the funds, causing online interest in COVID stimulus and relief programs to surge, and funds to quickly run out.

Subsequently, we noticed that phishing attacks related to government relief programs increased by 600% in April 2020. In Figures 10-11, we show an example of a phishing page pretending to represent the “U.S. Trading Commission,” a fake branch of the U.S. federal government that the FTC warned about. The website promises up to $5,800 in “Temporary Relief Fund” grants for each individual. Fake statistics are displayed on the right-hand side of the page, giving the user the illusion that there are still billions of dollars left to distribute.

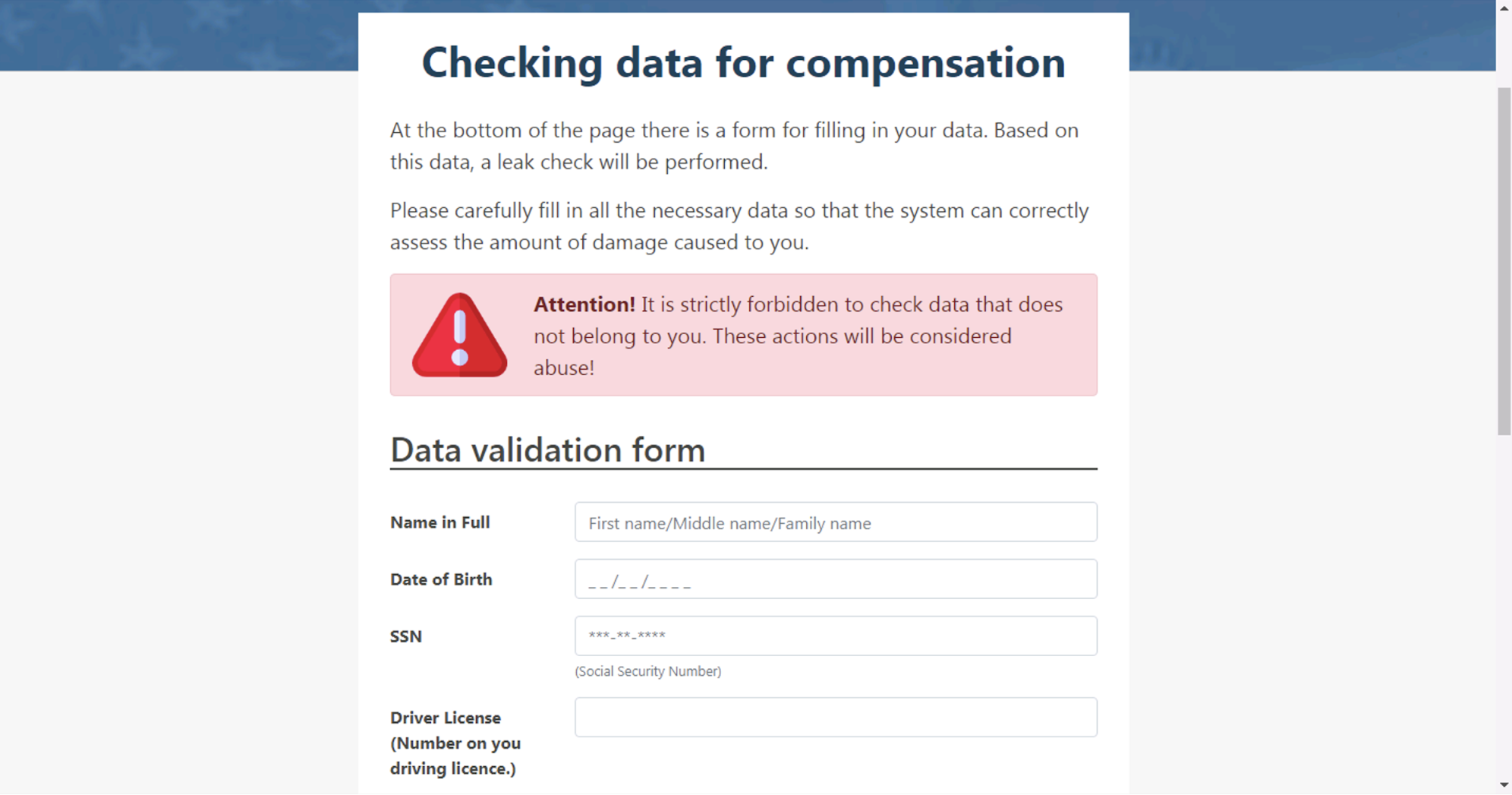

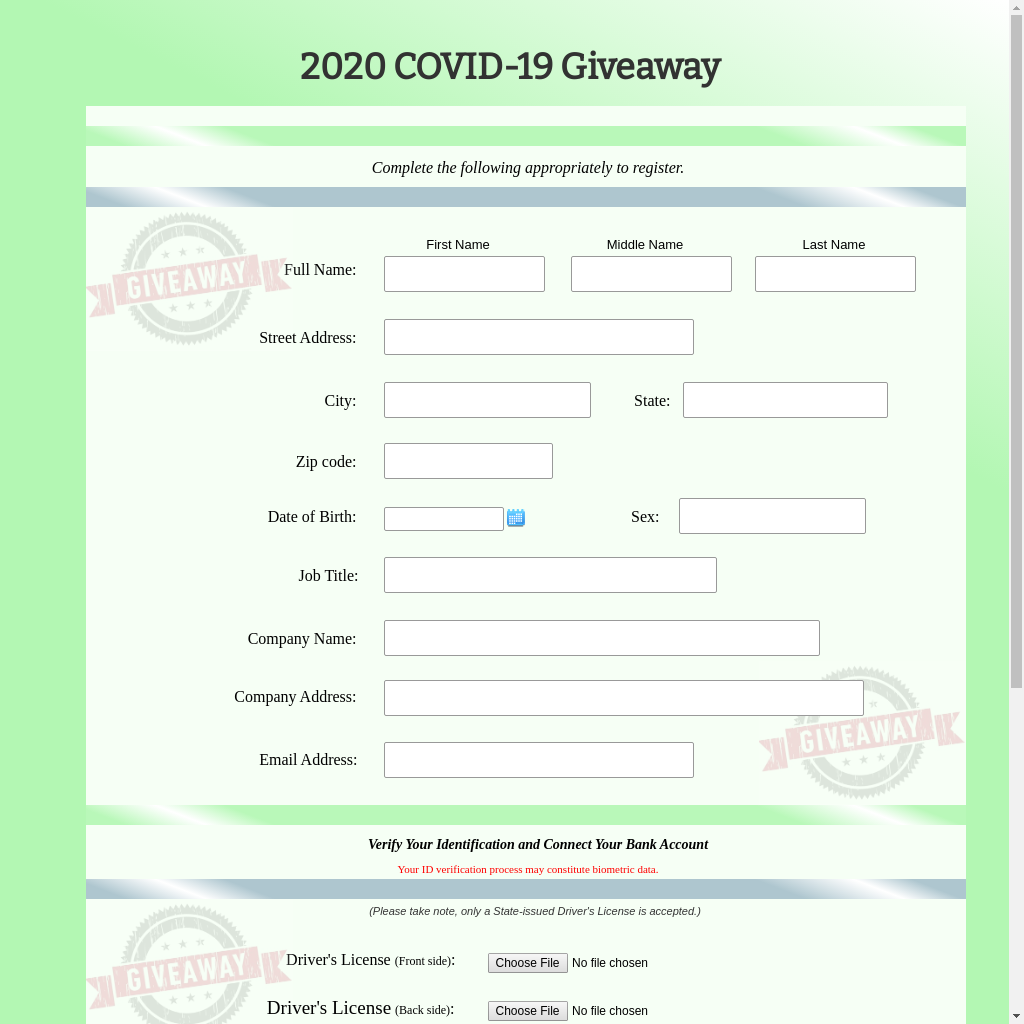

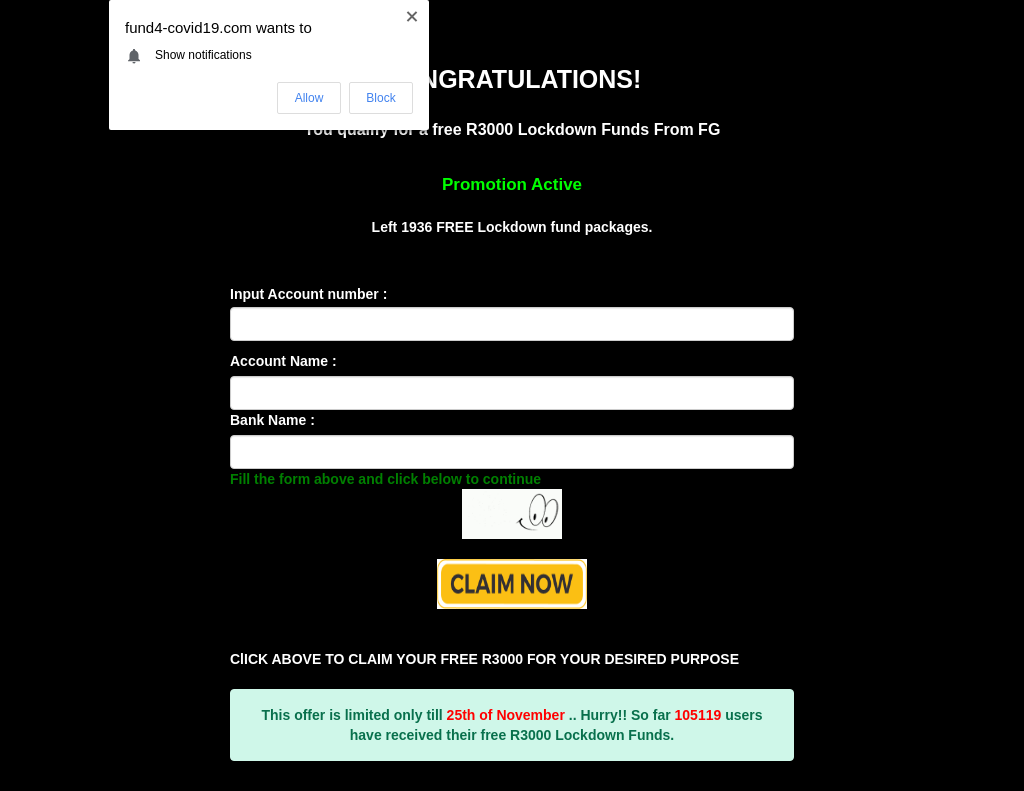

After the legitimate stimulus and relief programs were put in place, these economic relief-related phishing attacks stayed relatively popular for the months to come (see Figure 9), as many people were still in need of financial support. In Figure 12, we see another credential stealing page asking the user to input personal and corporate information, driver’s license photo and bank account details in order to receive additional relief funds from a “COVID-19 giveaway.” We see a similar example in Figure 13, which promises to send the user a free lockdown fund package of 3000 Indian rupees after inputting their bank account information.

November 2020-February 2021: Vaccine Approval and Rollout

For the next several months, various states settled into a state of on-and-off lockdowns, while people awaited news of a potential vaccine.

In November 2020, after months of anticipation, Pfizer and BioNTech released a promising set of initial results, showing over 90% vaccine effectiveness based on a subset of 94 participants in their real-world trial. In December, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted emergency use authorization for Pfizer’s mRNA vaccine, after which the vaccine rollout began.

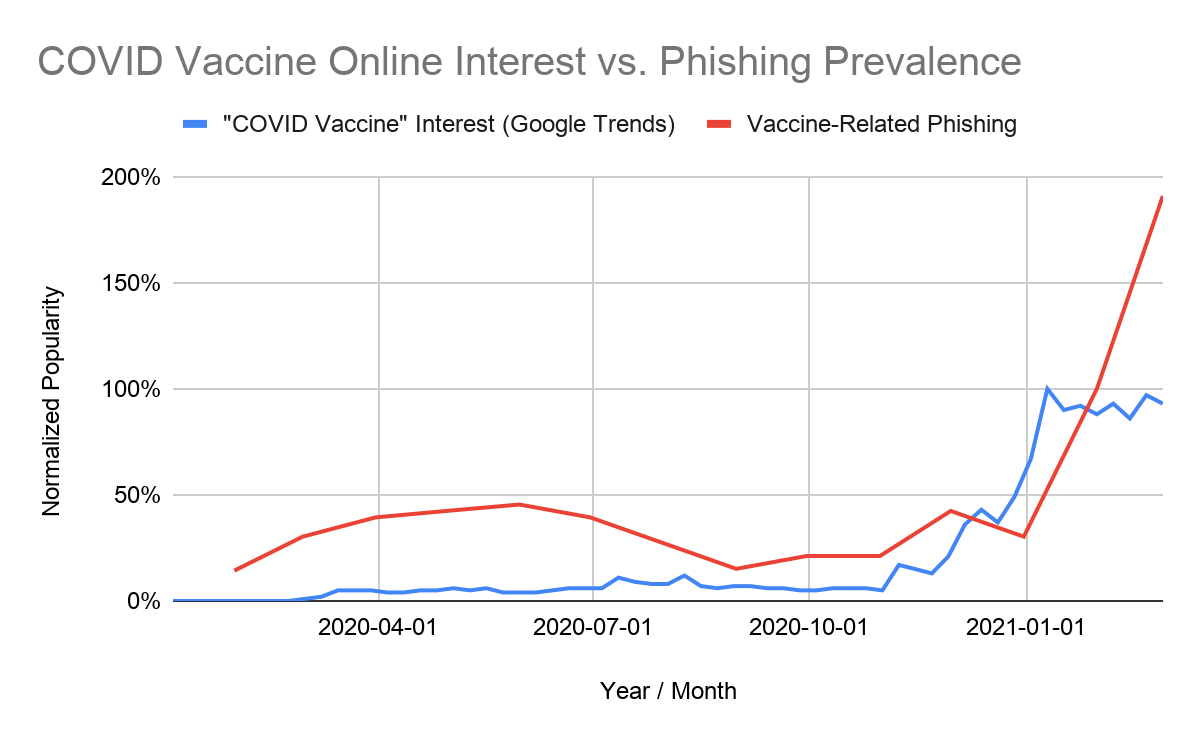

With many Americans now looking for a way to sign themselves and their family members up for immunization, it should be no surprise that cybercriminals would try to use this trend to their advantage. From December 2020 to February 2021, we observed a 530% increase in vaccine-related phishing attacks (see Figure 14).

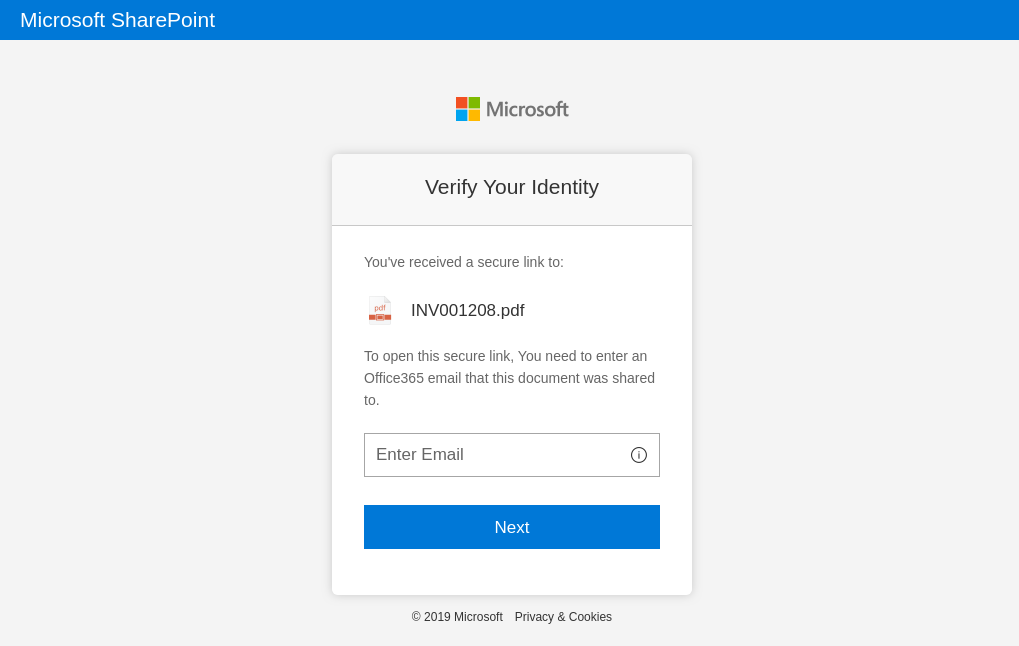

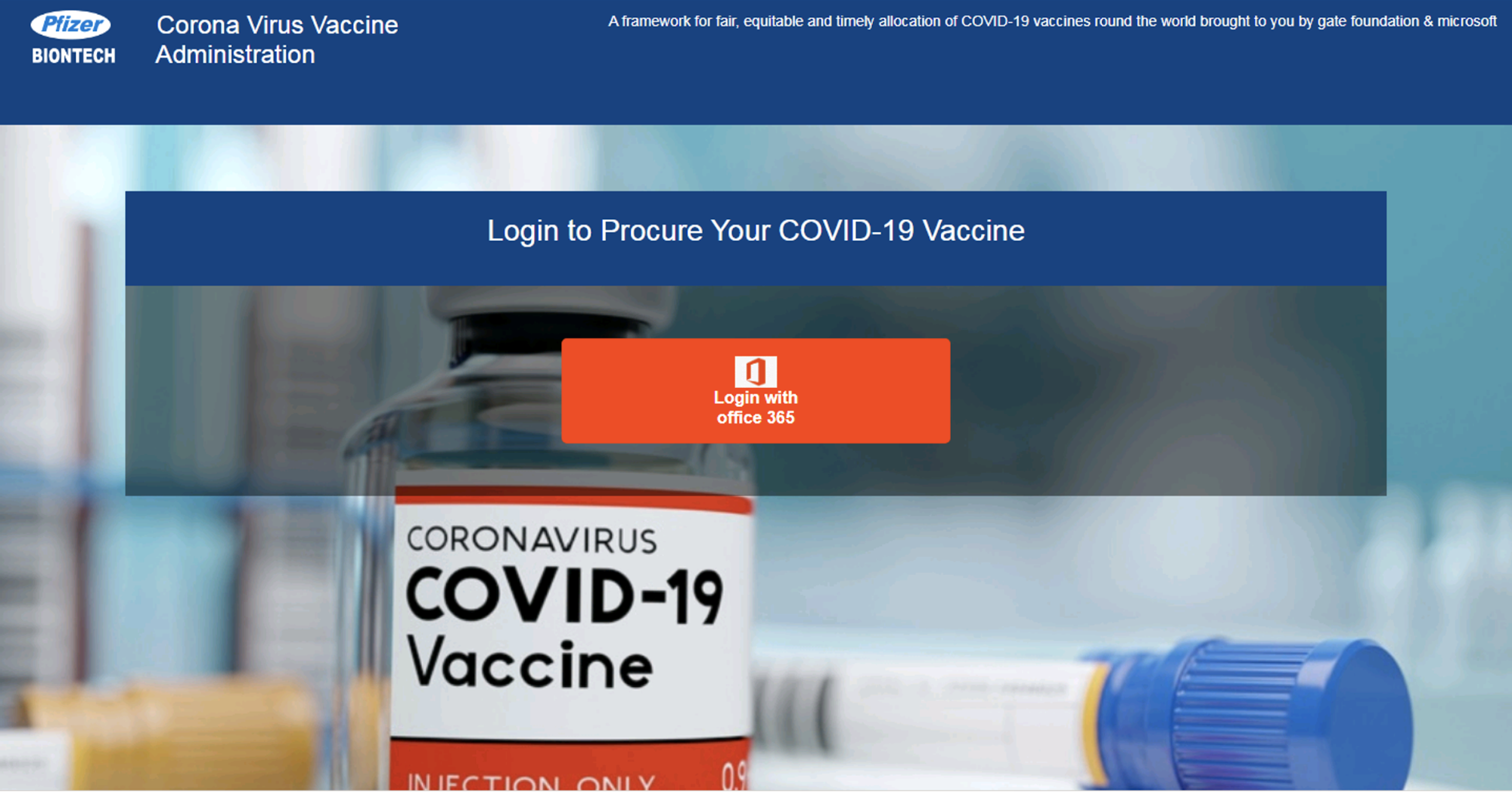

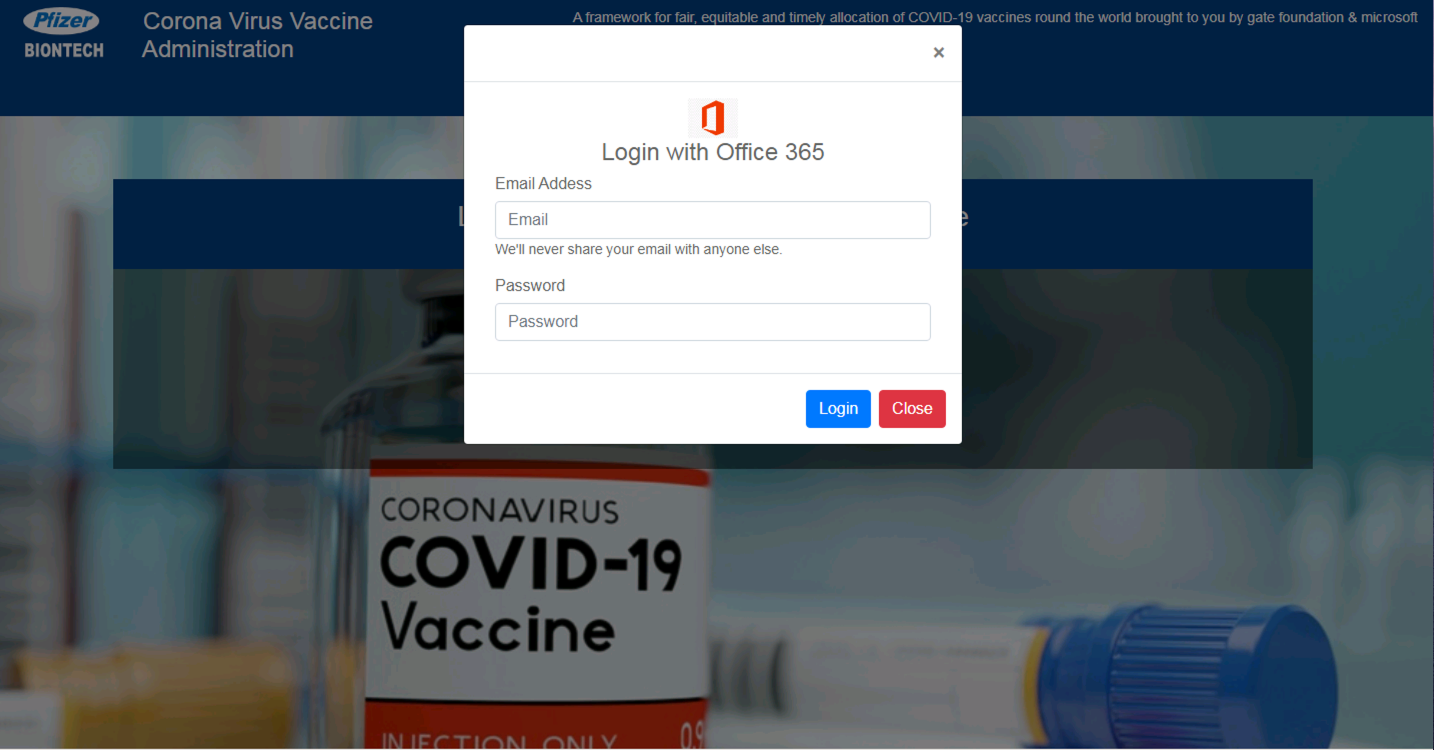

In Figures 15-16, we show an example of a fake website that claims to represent Pfizer and BioNTech, the makers of the mRNA vaccine. The phishing page asks the user to log in with his or her Office 365 credentials, supposedly in order to sign up for the vaccine.

Also note that this phishing website employs an increasingly common technique known as “client-side cloaking.” Rather than revealing the credential stealing form immediately, the website first asks the user to click the “Login” button, in an effort to evade automated, crawler-based phishing detectors.

From December 2020 to February 2021, we observed a 189% increase in attacks related to pharmacies and hospitals. Many of these attacks are part of larger clusters of phishing campaigns, where several different URLs are sent to different employees of the same organization, in the hopes that at least one of the employees will mistakenly input his or her credentials into the fake login page.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the global nature of COVID-19, these phishing campaigns targeting pharmaceutical and healthcare companies seem to be prevalent worldwide, not just in the U.S.

In certain cases, we also observe legitimate pharmaceutical companies whose websites have been compromised and used for phishing purposes. In Figure 17, we can see that a website belonging to a global life sciences technology marketplace company which had been compromised and used to host a phishing page for stealing users’ business credentials. These sorts of attacks can be particularly dangerous, as the legitimacy of the original website may trick users into incorrectly thinking that the phishing page is also legitimate.

![pharmalicensing[.]com, a website belonging to a company that helps connect businesses across the life sciences industry, had been compromised and used to host a phishing page for stealing users’ business credentials.](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/word-image-118.png)

Conclusion

At various points during the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen attackers shift their focus from one topic to another depending on the current state of events. In the early stages of the pandemic, testing kits and PPE were a significant area of focus for attackers. The focus then shifted to government stimulus and relief programs, before pivoting again to the vaccine rollout. As we have seen, attackers continually adapt to the newest trends. As a result, cybersecurity defenses must adapt as well.

Individuals should continue to exercise caution when viewing any emails or websites claiming to sell any goods or services or provide any benefits related to COVID-19. If it seems too good to be true, it most likely is. Employees in the healthcare industry in particular should view links contained in any incoming emails with suspicion, especially from emails trying to convey a sense of urgency.

General best practices to protect yourself and your organization from phishing attacks include:

For individuals:

- Exercising caution when clicking on any links or attachments contained in suspicious emails, especially those relating to one’s account settings or personal information, or otherwise trying to convey a sense of urgency.

- Verifying the sender address for any suspicious emails in your inbox.

- Double-checking the URL and security certificate of each website before inputting your login credentials.

- Reporting suspected phishing attempts.

For organizations:

- Implementing security awareness training to improve employees’ ability to identify fraudulent emails

- Regularly backing up your organization’s data as a defense against ransomware attacks initiated via phishing emails.

- Enforcing multi-factor authentication on all business-related logins as an added layer of security.

For more specific suggestions that individuals and organizations can use to protect themselves, see “COVID-19: The Cybercrime Gold Rush of 2020.”

In addition to these general best practices, Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall customers are protected from these threats in multiple ways:

- URL Filtering has properly classified all of the phishing URLs mentioned in this blog, and will continue to automatically detect and block newly created phishing pages in the future.

- DNS Security can help identify malicious domains, such as typosquatting domains and newly registered domains (NRDs) used specifically to host targeted phishing attacks.

- Threat Prevention can be configured to support Credential Phishing Protection, ensuring that employees’ business credentials are not leaked outside their organization.

- Prisma Access and GlobalProtect provide complete cloud-delivered security for remote employees.

To learn more about how Palo Alto Networks can help protect your organization during the pandemic, please see our response to COVID-19.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Wei Wang, Wayne Xin, Jingwei Fan, Yu Zhang, and Seokkyung Chung for providing several data sources that were used in the analyses, and Jun Javier Wang, Kelvin Kwan, Vicky Ray, Laura Novak, Jen Miller-Osborn, Eddy Rivera and Erica Naone for their help with improving the blog.

Indicators of Compromise

COVID-19

covid-19-benefit[.]cabanova[.]com

abccoronavirus[.]online

cpvqapyxmr[.]covid19coronaca[.]net

sign-amazonsnews-alert[.]peduli-covid19.com

Vaccines

vaccine-sarscov2[.]online

sarscov2vaccine[.]online

universalvirusvaccine[.]com

pittsburgh-coronavirus-vaccine[.]online

nhs-vaccination.com

pfizersupply.eu

covid-19vaccine[.]uscis-gov[.]online

Testing

covid-testkit[.]co[.]uk/wp-includes/images/i/Newfilesviewc7c782c3b7c54f958e7eb2efff3a49b28866b4fc22dd46cfbad9e6ac9d0cd18cca873584897b48c88d82ecf5cd62783dServices

sarscov2-test[.]online

y2down[.]xyz/unreadmessages/testkits

PPE

maskacoronavirus[.]online

maskakoronawirus[.]online

malibumasks[.]com/.offce365/?

cloroxus[.]com

www[.]lysolmz9[.]top

atemmaske-kn95-de[.]com

Drugs and Pharmaceuticals

veklury-covid19[.]online

covid19-veklury[.]top

remdesivir-covid19[.]online

covid19-veklury[.]online

covispharmac[.]com

Pharmacies and Hospitals

jyhhospitaljp[.]com

neelkantcollegeofpharmacy[.]com/images/icon/invntce/shoffpro/sharepoint/verification.php

www[.]afbiohavenpharma.com.dailyoffercode.com

www[.]afamagpharma.com.dulcerialamejor.com

www[.]afbiohavenpharma.com[.]diasahabatku[.]com

www[.]afbiohavenpharma.com[.]besttodaymart[.]com

Economy and Government Programs

disvey[.]ir/authcovid-19reliefgov

covid-stimulus-payment[.]gov[.]free-inhabitant[.]com

hellos[.]tcp4[.]me/Standard-Bank-Online-Relief-Funds-UCount-onlinebanking.standardbank.co.za-direct-login/Standard%20Bank%20Online%20Banking.htm

hmrc[.]covid[.]19-support-grant[.]com

fund4-covid19[.]com

furlough-grant[.]com

covid19emergencyfinancialrelief[.]com

Gathering Remotely

zoominceinvite[.]s3[.]amazonaws[.]com/invitezoom08.html

bit[.]ly/zoomtroubleshoot

us02web[.]zoom[.]us[].]coremailxt5mainjsp[.]com

incoming[.]zoomcallrequest[.]org

zoom-free1[.]com

zoommeetinactivation[.]web[.]app

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42