Executive Summary

Newly registered domains (NRDs) are known to be favored by threat actors to launch malicious campaigns. Academic and industry research reports have shown statistical proof that NRDs are risky, revealing malicious usage of NRDs including phishing, malware, and scam. Therefore, best security practice calls for blocking and/or closely monitoring NRDs in enterprise traffic. Despite the evidence, there hasn’t yet been a comprehensive case study on the malicious usages and threats associated with NRDs using real world examples. This blog presents that comprehensive case study and analysis of malicious abuses of NRDs by bad actors.

We have been tracking NRDs for more than nine years. We collaborate with the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) and various domain registries and registrars, which provides us direct visibility of many NRDs registered under both generic top-level domains (gTLDs) and country-code top-level domains (ccTLDs). We also indirectly identify NRDs by leveraging a combination of data sources, including WHOIS, zone files, and passive DNS. Our proprietary NRD feed consists of 1,530 top-level domains, which to our knowledge exceeds the best NRD feed/service publicly offered on the market.

Our analysis shows that more than 70% of NRDs are “malicious” or “suspicious” or “not safe for work.” This ratio is almost 10 times higher than the ratio observed in Alexa’s top 10,000 domains. Also, most NRDs used for malicious purposes are very short-lived. They can be alive only for a few hours or a couple of days, sometimes even before any security vendor can detect it. This is why blocking NRDs is a necessary, preventive security measure for enterprises.

In this blog, we present some high-level statistics on recent NRDs, demonstrate the malicious usage and threats associated with them through case studies and conclude with a discussion of best practices.

High Level Statistics

Volume

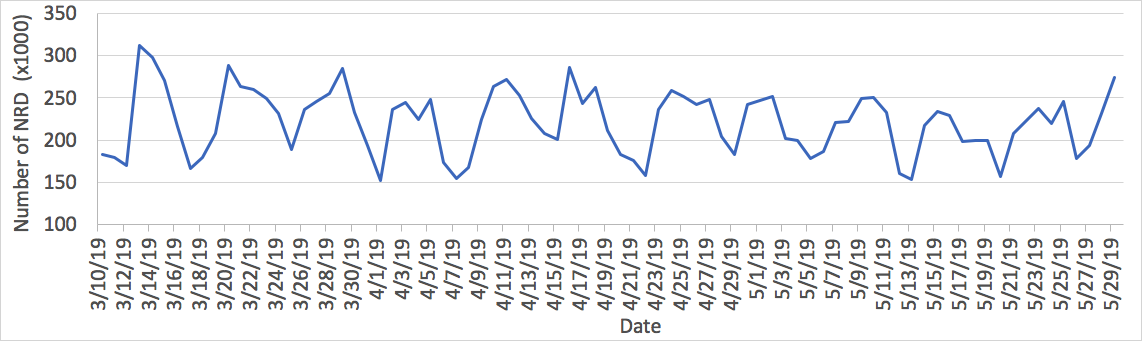

Our system identifies, on average, about 200,000 NRDs every day. The total volume fluctuates between 150,000 and 300,000. Figure 1 displays the volume of NRDs from March 10 to May 29, 2019. In general, there are consistently more NRDs registered on weekdays than weekends, with the peak usually on Wednesday and low on Sunday.

Figure 1. Volume of daily NRDs.

Figure 1. Volume of daily NRDs.

Distribution of TLDs

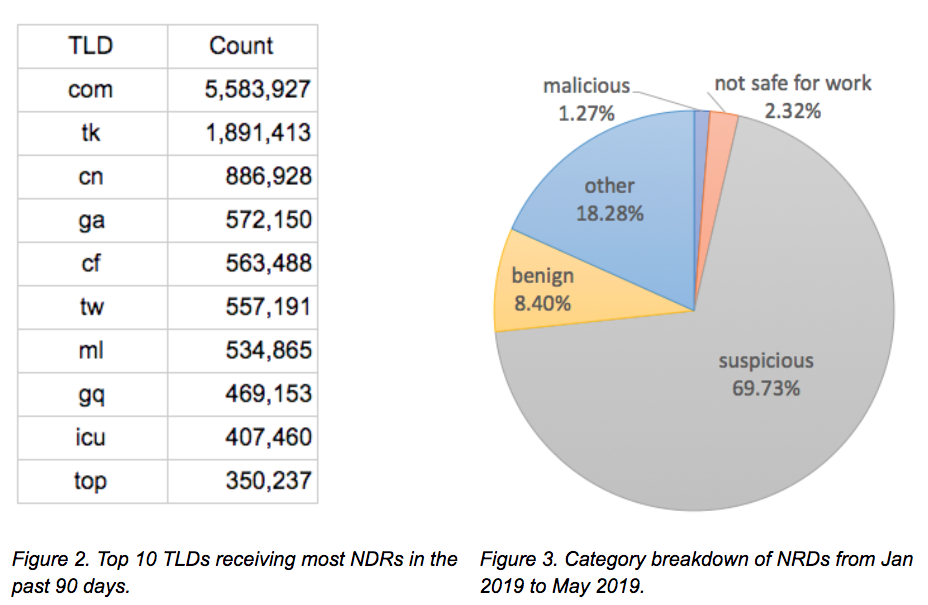

Not every TLD has new registrations every day. On average, there are between 600 and 700 unique TLDs showing up in daily NRDs. Figure 2 lists the top 10 TLDs with the most registrations. The distribution is averaged over a dataset of three months, from March to May 2019. As one can see, .com is still the most popular TLD even though it was introduced 34 years ago (March 15, 1985). It accounts for 33% of all recent NRDs.

The second position changes over time, but mainly among a few ccTLDs including .tk, .cn, and .uk. For example, .cn remained in second place from November to December 2018. However, from March to May 2019, .tk was consistently in second place. Those ccTLDs get large numbers of of NRDs because they offer free domain registrations (e.g. .tk, .ml, .ga, .cf and .gq).

Usage of NRDs

In order to understand the purpose of these new registrations, we cross-check these domains against categories assigned by our PAN-DB URL Filtering service. This service categorizes a URL through a group of techniques including web content crawling, malware traffic analysis, passive DNS data analysis, machine learning, and deep learning. For simplicity, we group the categories into five classes: “malicious” “suspicious” “not safe for work” “benign” and “other.” For malicious URLs, we have three categories, namely Malware, Command and Control (C2), and Phishing. For suspicious URLs, we use categories Parked, Questionable, Insufficient Content, and High Risk. We tag Nudity, Adult, Gambling, and similar subjects as “not safe for work.” For benign URLs, we use Business & Economy, Computer & Internet Info, and Shopping. Anything not fitting into these categories falls into an “other” class. Figure 3 shows the breakdown of the five classes.

Over 70% of NRDs are marked malicious, suspicious, or not safe for work by our PAN-DB URL Filtering service. This ratio is almost 10 times higher than the ratio observed in Alexa’s top 10,000 domains, which is only 7.6%. In addition, malicious categories accounts for about 1.27% of NRDs by our PAN-DB URL Filtering service. In Alexa top 10,000 domains, however, this ratio is only about 0.07%.

Malicious NRDs

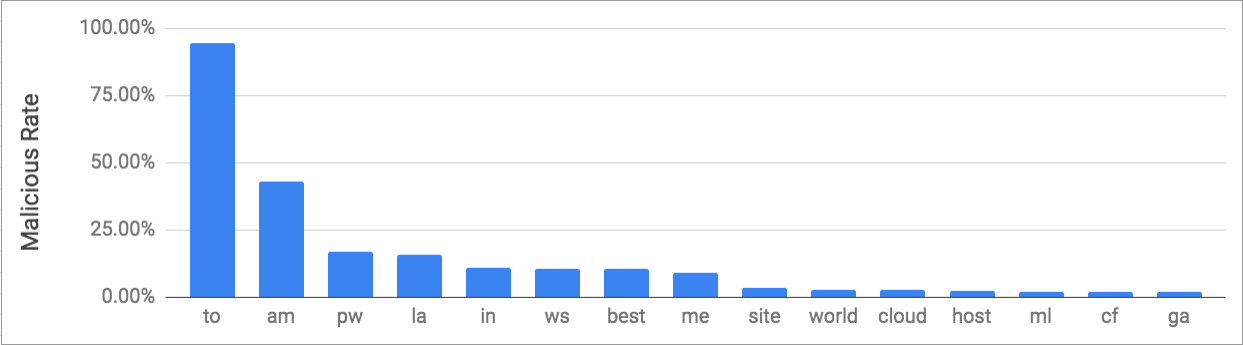

To further understand the characteristics of malicious NRDs, we checked and calculated the ratio of malicious NRDs for each TLD. Figure 4 lists the top 15 TLDs with the highest malicious rate on recent NRDs. Many of those are ccTLDs. Some reasons for a TLD to have a high malicious rate include inexpensive or free registration, a less strict registration policy, and obscuring WHOIS registrant data from public view.

Figure 4. Top 15 TLDs with the highest malicious NRD rate.

The original version of this blog listed different top 15 TLDs with the highest rate of malicious newly registered domains. Since publication we found that our analysis included some domains that were contacted by malware, but not actually registered. We re-evaluated the data and updated the chart to reflect the new analysis.

Malicious Usages and Threats

Now we discuss the malicious abuse of NRDs. We analyzed NRDs observed in our products and services, including URL Filtering, WildFire, and DNS Security. We found NRDs are associated with malicious usages and threats such as C2, malware distribution, phishing, typosquatting, PUP/Adware, and spam. Below are highlights from each category with real world examples.

C2 Domain

Malware typically needs to “phone home” in order to get commands, download further payloads, or perform data exfiltration. The malicious domain used for this purpose is called the command and control (C2) domain.

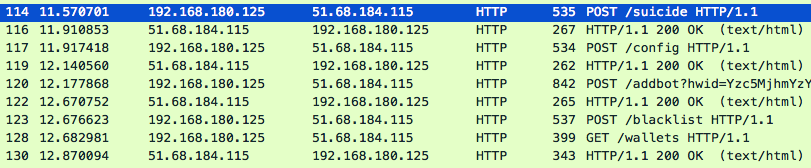

soroog[.]xyz was first registered on May 29, 2019 and we observed malware using this domain for C2 the same day. So far, we have seen seven AzoRult malware samples using this C2 domain. Malware belonging to this family can automatically collect sensitive data, including bitcoin wallet and credit card information.

Figure 5 captures a portion of the malware traffic wherein it’s actively communicating with the C2 soroog[.]xyz. This domain was initially hosted on the IP address 51.68.184[.]115. Based on our passive DNS records, the IP switched to 51.38.101[.]194 on June 24, 2019. This domain turned into NXDomain (non-existent domain) after June 26, 2019. As one can see, this domain was very short-lived. Actually, this is true for most NRDs used for malicious purposes. They are alive for only a few hours or a couple of days, sometimes even before any security vendor can detect it. That is why blocking NRDs is a necessary, preventive security measure.

Figure 5. Packet capture of AzoRult C2 traffic.

Figure 5. Packet capture of AzoRult C2 traffic.

Table 1 further enumerates the C2 URLs under this domain along with their usages. Readers with further interests in the behavior of this malware can refer to these two public analysis reports.

| URL | Usage |

| soroog[.]xyz/addbot | registering a new bot |

| soroog[.]xyz/wallets | sending out stolen information |

| soroog[.]xyz/suicide | reporting self-delete |

| soroog[.]xyz/task | registering a new task |

| soroog[.]xyz/cpu | sending out CPU information |

Table 1. C2 URLs and usages of AzoRult malware.

Malware Distribution

NRDs are commonly used for malware distribution. Here we use the Emotet malware family as an example. Emotet is a banking trojan that sniffs network traffic for banking credentials. Despite being discovered in 2014, it is still widely prevalent today. We have observed 50,000 unique samples so far in 2019. The initial delivery is usually through phishing attacks. As shown in Figure 6, the malicious DOC often comes as an attachment in a phishing email or from a compromised website. This DOC often primarily acts as a downloader and will download and execute a further payload. The downloading is normally via HTTP and we have observed thousands of downloading URLs. Many of them are hosted on NRDs.

Figure 6. Emotet malware distribution chain.

Figure 6. Emotet malware distribution chain.

For example, domain hvkbvmichelfd[.]info was registered on May 2, 2019. Only four days after that, on May 6, we saw an Emotet DOC using the URL hxxp://hvkbvmichelfd[.]info/skoex/po2.php?l=spond1.fgs to download a further payload. Interestingly, the payload further contacted another NRD halanis21yi84alycia[.]top to download a 2nd-stage payload (not shown in Figure 6). This second domain was also registered on May 2, 2019.

Readers who want to learn more about Emotet can refer to these two public blogs.

Phishing

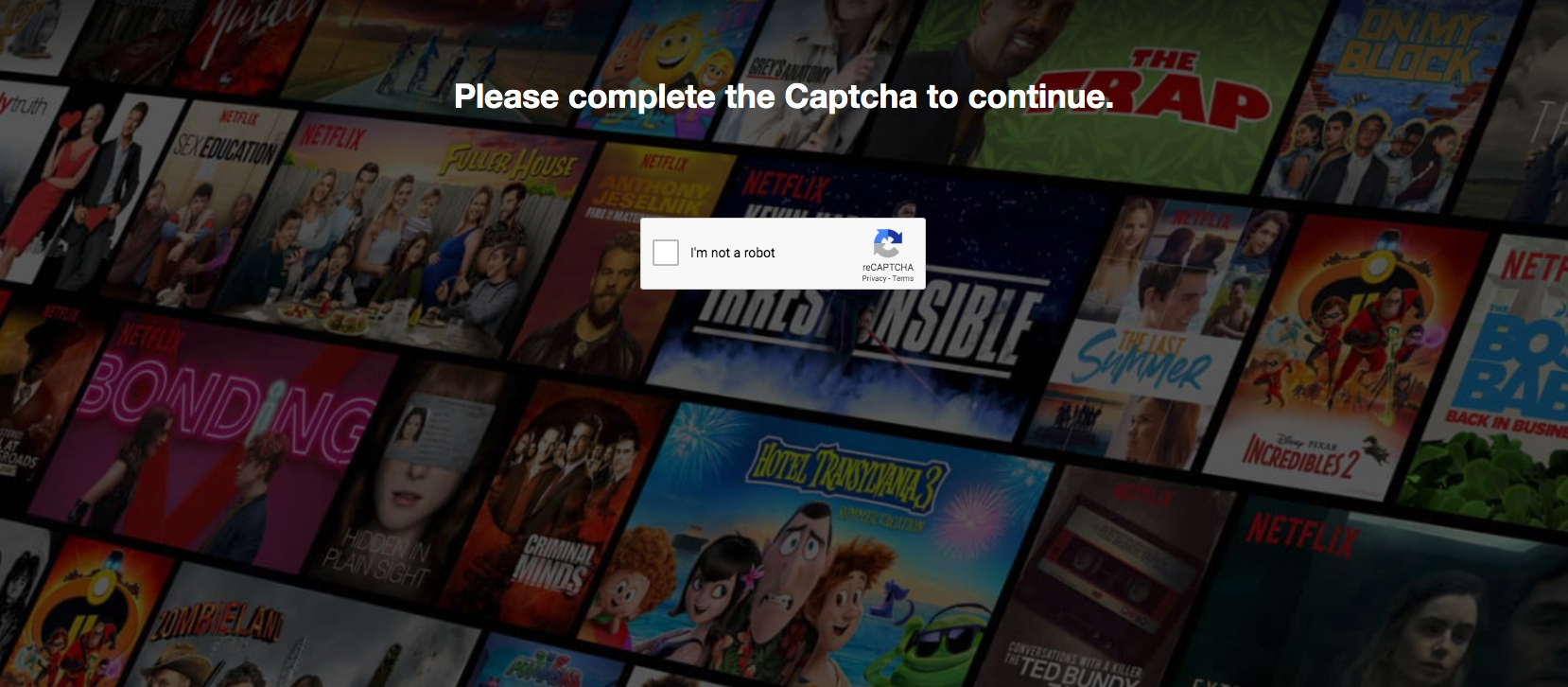

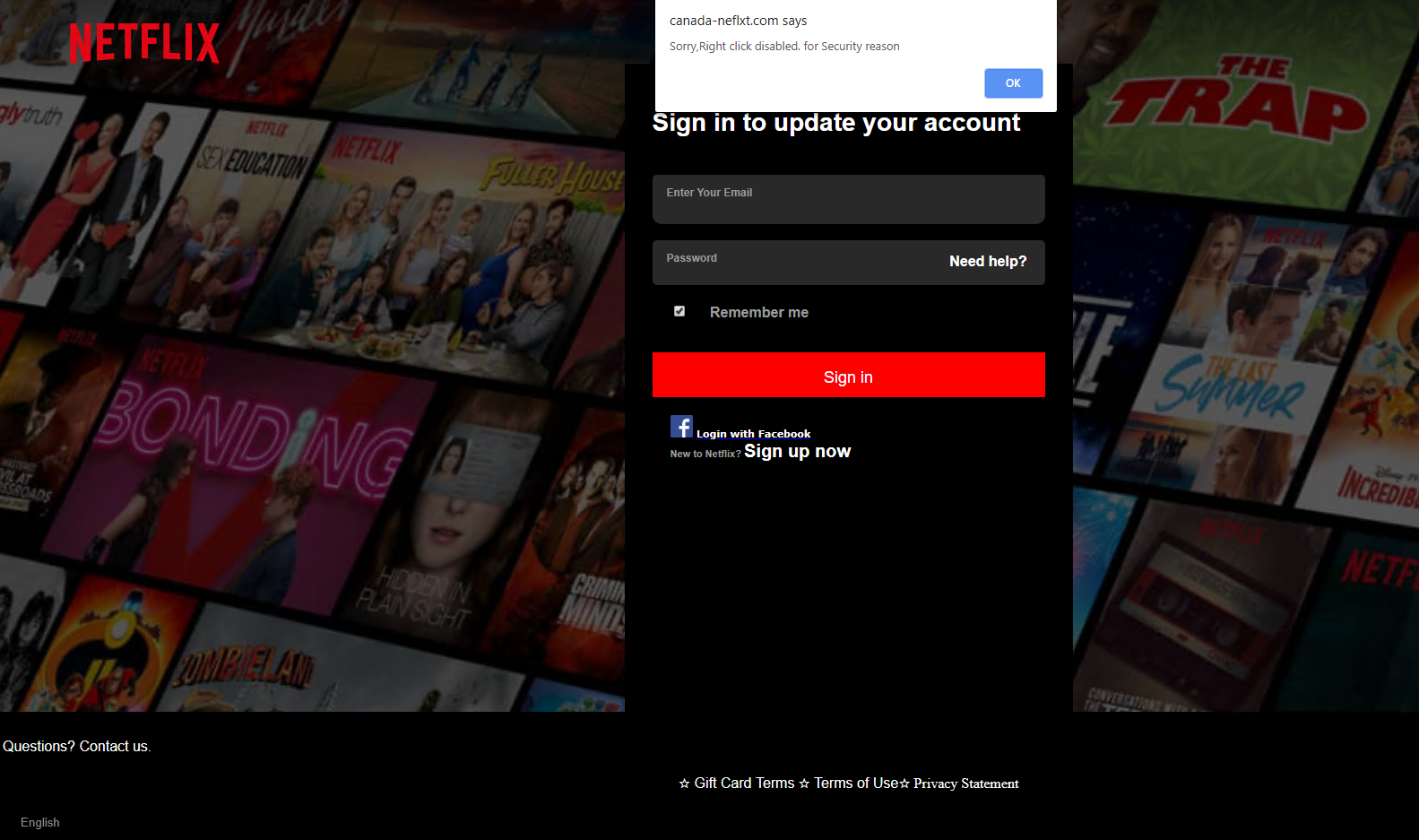

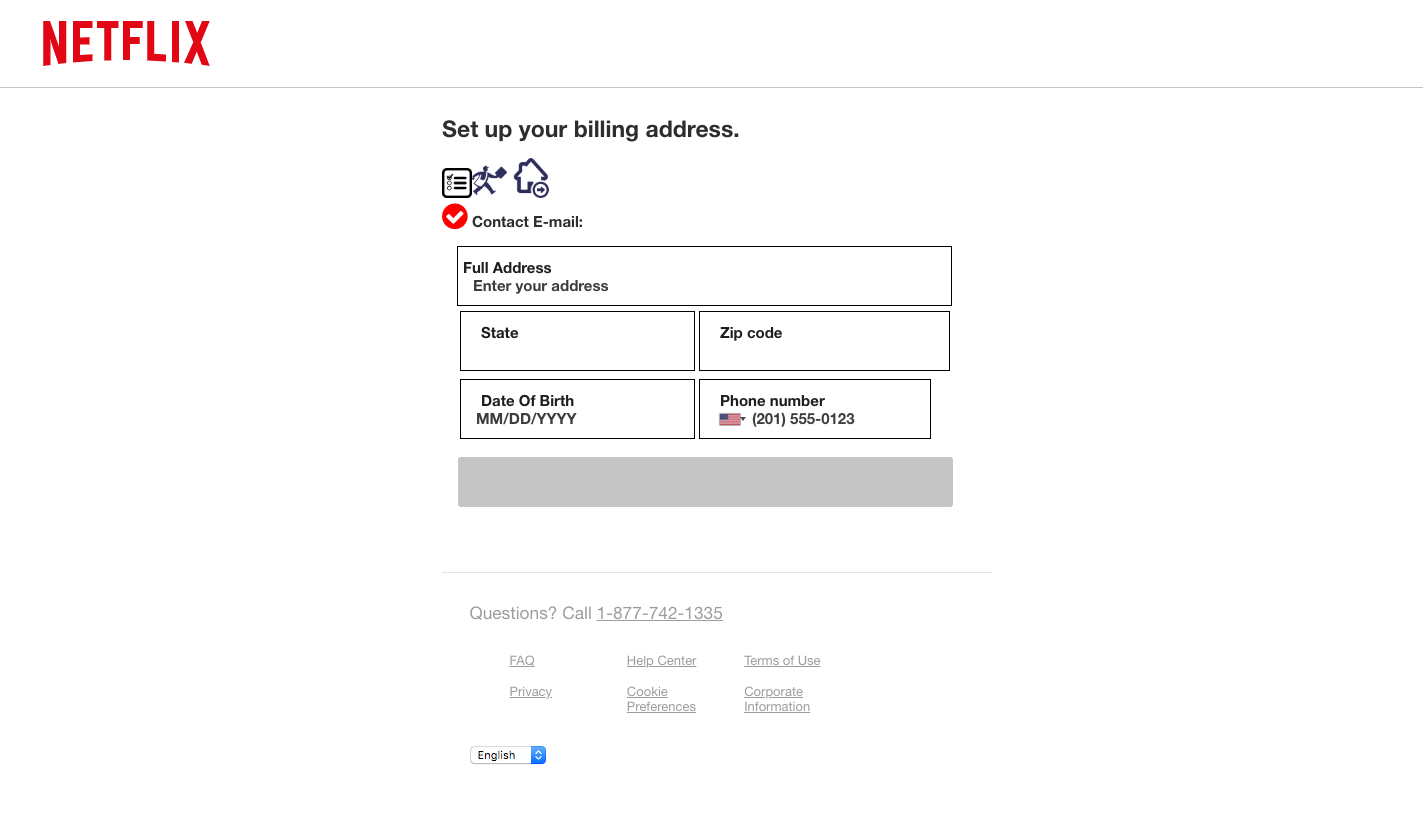

NRDs are also frequently used by phishing campaigns. The domain canada-neflxt[.]com was registered on July 4, 2019. According to our passive DNS record, we started to see traffic to this domain on July 6 and it was an active phishing site until July 17. It tries to steal victims’ Netflix credentials as well as billing information (Figure 10). There is another domain netflix-mail[.]ca also redirecting to canada-neflxt[.]com. This domain was registered on July 11.

This phishing website incorporated several techniques in order to hide it from automatic detection methods. For instance, the login page canada-neflxt[.]com/login (Figure 7a) utilizes a captcha to prevent crawlers from reaching further contents. In addition, right click is disabled on the login page (Figure 7b). We believe this is to prevent a victim from easily inspecting the website for page resources and network traffic. After entering an email and password, we observed unencrypted information being sent out. Next, the victim will reach a page for setting up billing information (Figure 7c).

Figure 7a. Login page with Captcha.

Figure 7a. Login page with Captcha.

Figure 7b. Login page with a login form and right click being disabled.

Figure 7b. Login page with a login form and right click being disabled.

Figure 7c. Billing page to collect billing information.

Figure 7c. Billing page to collect billing information.

Typosquatting

Domain typosquatting is a form of domain squatting that takes advantage of typos made by Internet users when typing a domain name into a web browser. There are three major ways to monetize a typosquatting domain. First, waiting to sell at a high price to the owner of the targeted domain (e.g. facebo0k[.]com as opposed to facebook[.]com). However, according to our analysis, big companies have been doing a reasonably good job in defensive registration. Plus, there are many brand monitoring/protection services to help with defensive registration. Therefore, it has become more and more difficult to make money in this way. Second, to serve ads or redirect the traffic to ads or competitors (for example, t-mogbile[.]com redirects to verizonwireless[.]com). The essential idea is to monetize the traffic. If the traffic volume is large enough to make more money than the registration fee (usually less than $10 per year), it is economically worthwhile to do this. Third, to serve malicious content like a phishing page, drive-by download of malware, etc.

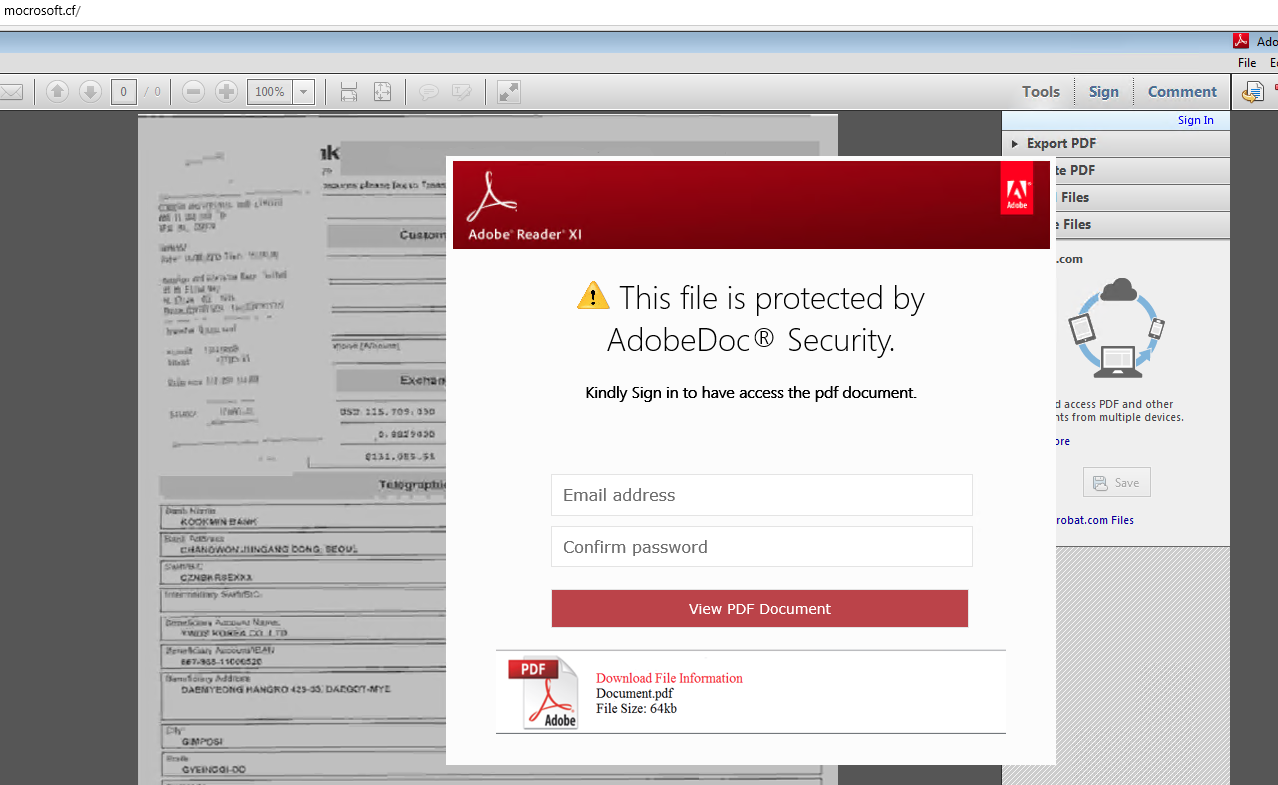

Typosquatting domains are widely observed in NRDs. As an example, domain mocrosoft[.]cf is likely a typosquatting domain targeted at Microsoft. This is because the letter “i” and “o” are next to each other on a typical keyboard and a typo is possible. This domain was first registered on June 3, 2019 and traffic to this domain was captured in our data on the same day. Figure 8 is the screenshot for browsing it using Microsoft Edge. Obviously, it's a phishing page trying to steal the users’ login credentials.

Figure 8. Phishing page with fake user login form.

Figure 8. Phishing page with fake user login form.

DGA

Domain generation algorithm (DGA) is a common approach used by malware to periodically generate a large amount of domains which can serve malicious purposes like C2 and data exfiltration. Most DGAs generate domains based on date and time. For example, Conficker C generates 50,000 domains every day. The huge volume of domains makes takedown efforts by law enforcement extremely difficult. However, the attacker knows the algorithm and thus can predict what domains will be generated on a particular date. So he or she only needs to register one or a few domains on demand. A large majority of DGA domains look very random.

As an example, ypwosgnjytynbqin[.]com is a DGA domain belong to Ramnit family. It was registered on July 3, 2019. Three days later on July 6, we observed a Ramnit sample (SHA256: 136896c4b996e0187fb3e03e13c9cf7c03d45bbdc0a0e13e9b53c518ec4517c2) talking to this domain.

Below in Table 2 are some additional examples where the malware communicating with DGA domains shortly after them being registered.

| C2 Domain | Registration Date | Malware SHA256 | Malware First Seen Date | Malware Family |

| eqbqcguiwcymao[.]info | 2019-01-17 | 6e812122f3067348580f06a1c62068cf7d3bf05a86e129396d51dd7666bcf7b9 | 2019-01-21 | Pykspa |

| aaqkekyaum[.]org | 2019-04-13 | 418dd3d94d138701f06c58ffb189dfae08c778fb9ad3859dbb7a301f299a8e55 | 2019-04-13 | Pykspa |

| qgasocuiwcymao[.]info | 2019-06-12 | 72748e6e2a3260e684f295eafcb8dd5b9927d15c41857435dfa28fd473eeccc4 | 2019-06-13 | Pykspa |

| litvxvkucxqnaammvef[.]com | 2019-04-11 | de51942e72483067aaeae3810bc4a24b8e12a782b3a59385989f9fccba08e421 | 2019-04-13 | Ramnit |

Table 2. DGA in NRDs and associated malware.

PUP and Adware

PUP stands for “potentially unwanted program,” which is adware in most cases. Adware may not really harm the system at the same level as a malware does. However, it usually performs unwanted changes to the system like changing the browser's default page, hijacking the browser to insert ads, etc. Sometimes a PUP/Adware’s infrastructure can be repurposed for malware in campaigns, affecting those hosts running the PUP.

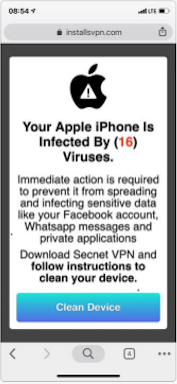

installsvpn[.]com was created for PUP distribution. First registered on May 10, we started to see this domain serving PUP on May 16. In particular, this is an adware targeted at iPhone users. Figure 9 shows the fake virus pop-up message, which tries to lure the user to download and install the “Secret VPN” tool. To bypass detection, this website retrieves the OS information and display warnings only for iPhones. For other systems, an empty page is returned.

Figure 9. Fake virus warning pop-up

Figure 9. Fake virus warning pop-up

Another example is the domain llzvrjx[.]site, which was registered on June 12 and became active on June 14. It’s an adult website offering a free streaming video app. We analyzed the Android version of this app and found this app comes with unwanted permissions like ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION, SEND_SMS, and READ_CONTACTS. This website also targets at mobile users. It has a cloaking JavaScript to hide itself from desktop users or crawler through checking the browser’s user agent.

Scams

Other than phishing scams which mainly attempt to obtain user credentials like username and password, there are other types of online scams. According to our analysis, these scams also rely on NRDs. Below are a few examples.

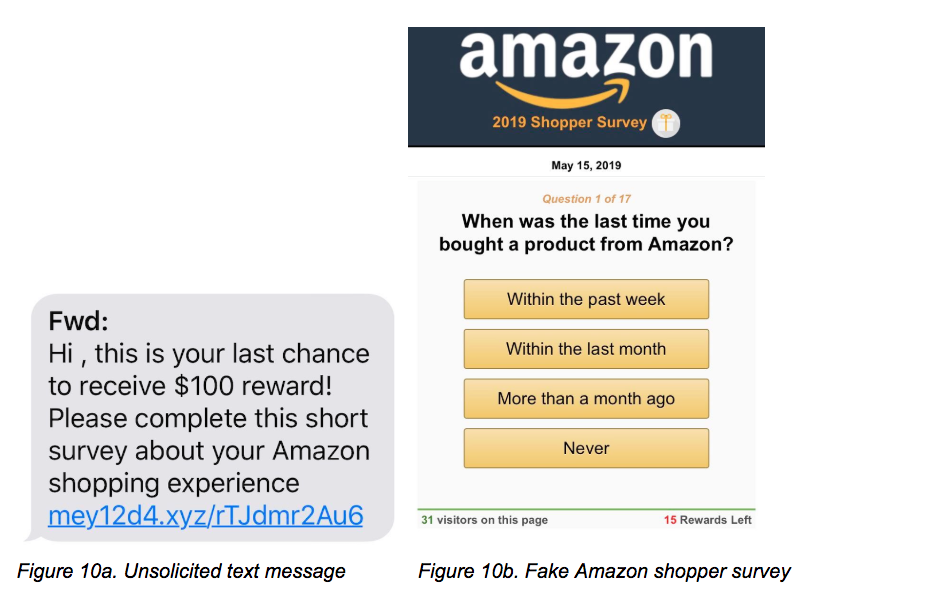

Reward scam: The domain mey12d4[.]xyz was registered on May 13, 2019. On the same day, we noticed a campaign where this domain is embedded in an unsolicited text message sent to victims, as shown in Figure 10a. The text message uses $100 reward as an incentive for users to click the link. Once opened in a browser, it will go through a series of redirections and finally land on a fake Amazon survey page, as shown in Figure 10b. We clicked through the survey and got to a page asking for personal information like credit card and home address.

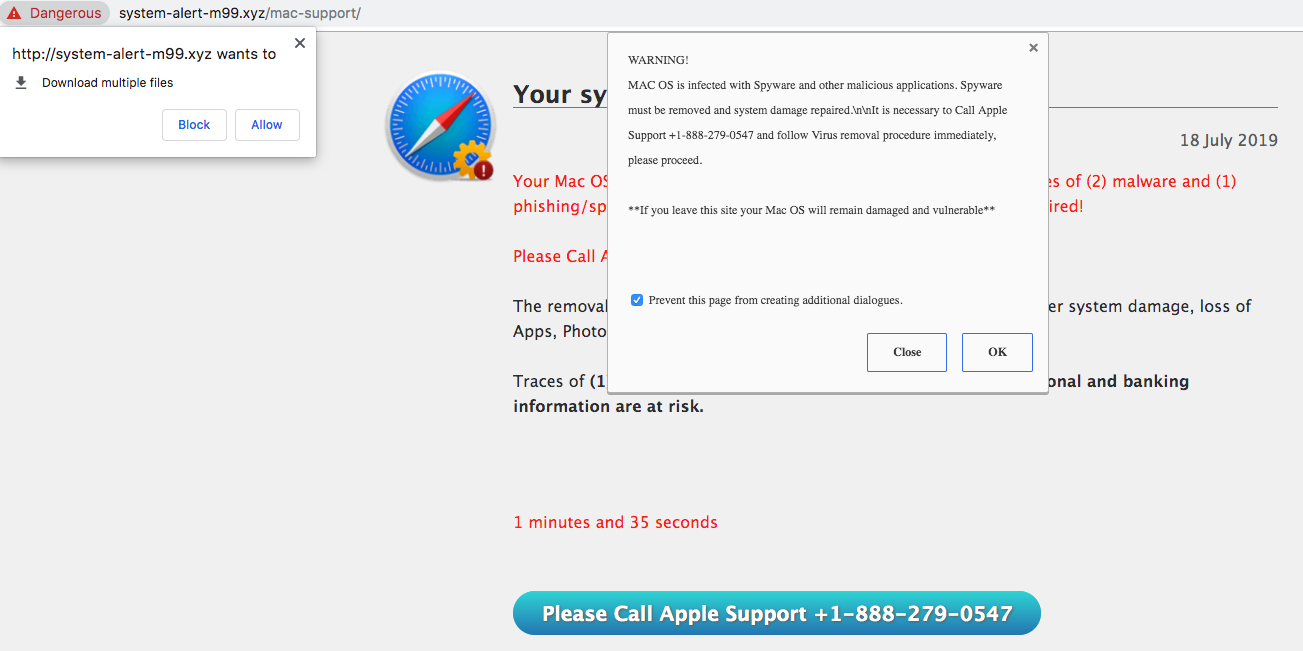

Tech support scam: This type of scam relies on social engineering via phone calls claiming to provide a legitimate technical support service. Victims are often times tricked to install remote desktop access tools and/or pay for the “support” by giving out credit card information. The scams usually begin with a web page suggesting the computer is compromised and instructing the victim to call the support number. Figure 11 shows a running example. This page is hosted on the domain system-alert-m99[.]xyz, which is registered on July 17, 2019. On the same day, it started to serve the tech support scam page.

Figure 11. A typical tech support scam webpage

Figure 11. A typical tech support scam webpage

Re-bill scam: A recent Unit 42 blog talked about the “re-bill” scam. Basically, victims are lured to pay a small amount of money to get a trial of a product like weight loss pills. However, there is a tiny fine print stating that “if you don’t cancel your subscription within X-amount of time then you will be charged a much higher amount of money on a recurring basis”. The amount can be $50-$100 per each surprising credit card bill. Most domains used in such scams are NRDs. For example, ketoweightlosspillsreviews[.]com was recently registered on June 1, 2019. For additional information on this type of scam, please refer to this blog.

Email Spam

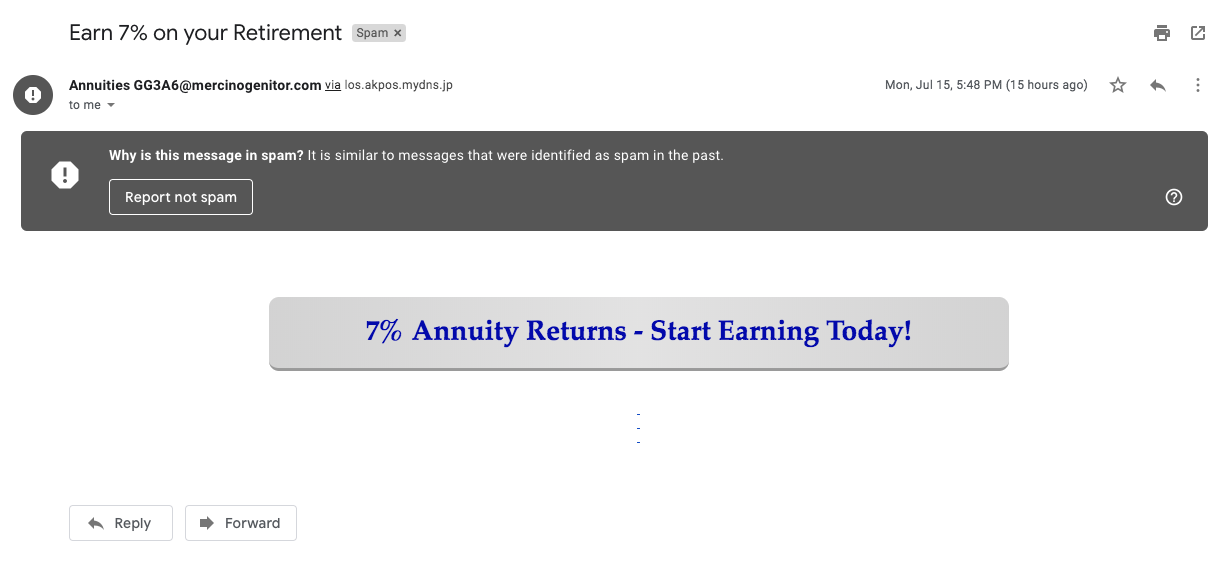

Spam emails are unsolicited messages sent to bulk email addresses that are harvested in different ways. The purpose of spam emails varies from advertising to spear phishing. Figure 12 shows a spam email distributing advertisements on retirement savings. It is sent through mercinogenitor[.]com, which was registered on July 4, 2019. The spam email was received on July 15. Unsurprisingly, Gmail detected it as spam at the time of receipt.

Figure 12. A spam email sent from NRD.

Figure 12. A spam email sent from NRD.

Conclusion

In sum, newly registered domains (NRDs) are often times abused by bad actors for nefarious purposes, including but not limited to C2, malware distribution, phishing, typosquatting, PUP/Adware, and spam. At the same time, there are benign uses as well, such as launching a new product, creating a new brand or campaign, hosting a new conference, or building a new personal site.

At Palo Alto Networks, we recommend blocking access to NRDs with URL Filtering. While this may be deemed a bit aggressive by some due to potential false-positives, the risk from threats via NRDs is much greater. At the bare minimum, if access to NRDs are allowed, then alerts should be set up for additional visibility. We define NRDs as any domain that has been registered or had a change in ownership within the last 32 days. Our own analysis has indicated that the first 32 days is the optimal time frame when NRDs are detected as malicious.

As seen in the TLD section of this blog, we would even go as far as to recommend blocking complete TLDs (Figure 4) that are mainly utilized by bad actors. Of course, each organization must understand what their tolerance is for potential false-positives when blocking whole TLDs.

Palo Alto Networks customers are all protected against malicious indicators (domain, IP, URL, SHA256) mentioned in this blog, via URL Filtering, DNS Security, WildFire, and Threat Prevention where applicable. AutoFocus customers with further interests in the malware mentioned in this blog can refer to AutoFocus tags AzoRult, Emotet, Pykspa, and Ramnit.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42