This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

Early this year, Ukrainian cybersecurity researchers found Fighting Ursa leveraging a zero-day exploit in Microsoft Outlook (now known as CVE-2023-23397). This vulnerability is especially concerning since it doesn’t require user interaction to exploit. Unit 42 researchers have observed this group using CVE-2023-23397 over the past 20 months to target at least 30 organizations within 14 nations that are of likely strategic intelligence value to the Russian government and its military.

During this time, Fighting Ursa conducted at least two campaigns with this vulnerability that have been made public. The first occurred between March-December 2022 and the second occurred in March 2023.

Unit 42 researchers discovered a third, recently active campaign in which Fighting Ursa also used this vulnerability. The group conducted this most recent campaign between September-October 2023, targeting at least nine organizations in seven nations.

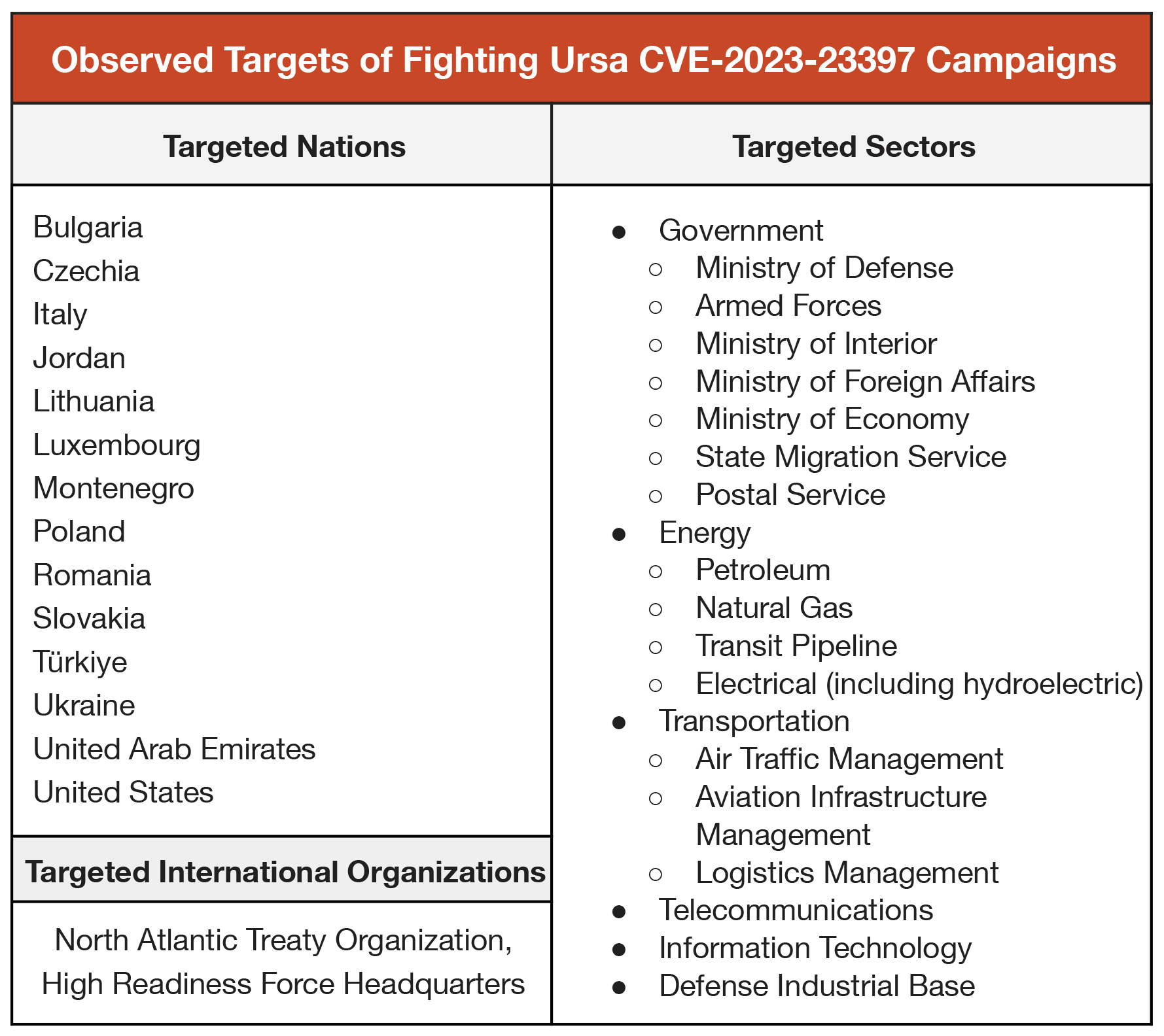

Of the 14 nations targeted throughout all three campaigns, all are organizations within NATO member countries, except for entities in Ukraine, Jordan and the United Arab Emirates. These organizations included critical infrastructure and entities that provide an information advantage in diplomatic, economic and military affairs.

Target organizations included those related to:

- Energy production and distribution

- Pipeline operations

- Materiel, personnel and air transportation

- Ministries of Defense

- Ministries of Foreign Affairs

- Ministries of Internal Affairs

- Ministries of the Economy

Fighting Ursa (aka APT28, Fancy Bear, Strontium/Forest Blizzard, Pawn Storm, Sofacy or Sednit) is a group associated with Russia’s military intelligence and they are well known for their focus on targets of Russian interest – especially those of military interest. Fighting Ursa has been attributed to Russia's General Staff Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU) 85th special Service Centre (GTsSS) military intelligence Unit 26165.

We are publishing this research to highlight Fighting Ursa using this vulnerability in multiple campaigns despite their tactics having been publicized by security industry research documenting this activity. High risk organizations and nations using Microsoft Outlook should patch CVE-2023-23397 immediately and ensure appropriate configuration to defend against future attacks.

Palo Alto Networks customers receive protection with the following products against the types of threats discussed in this blog:

- Cortex XDR

- WildFire

- Advanced URL Filtering

- Advanced Threat Prevention

- DNS Security subscription services for the Next-Generation Firewall

- Organizations can engage the Unit 42 Incident Response team for specific assistance with this threat and others

| Related Unit 42 Topics | Russia, Ukraine |

| Fighting Ursa APT Group AKAs | APT28, UAC-0001, Fancy Bear, Strontium / Forest Blizzard, Pawn Storm, Sofacy, Sednit |

CVE-2023-23397: A Brief Overview

Prior to the conflict in Ukraine, Fighting Ursa had established a reputation for its hacking in support of Russia’s information warfare operations. This support includes the following efforts:

- Countering Olympic anti-doping investigation narratives

- Subverting an investigation into the use of chemical agents in an assassination attempt by the GRU in Great Britain

- Influencing democratic election processes in the United States, France and Germany

Less internationally well known are Fighting Ursa’s collective hacking campaigns in the lead-up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine through today.

On Feb. 24, 2022, Russia initiated a full-scale armed invasion of Ukraine. Three weeks later (March 18, 2022), Fighting Ursa emailed the first known instance of an exploit using the CVE-2023-23397 vulnerability (which was then a publicly undiscovered zero-day exploit) to target the State Migration Service of Ukraine.

Fighting Ursa continued to use this vulnerability as part of its targeting strategy even after Ukrainian cybersecurity researchers discovered the exploit and Microsoft publicly attributed its use to “a Russia-based threat actor” on March 14, 2023, when issuing a patch for the vulnerability.

Overall, Unit 42 researchers have observed three distinct Fighting Ursa campaigns associated with this CVE:

- Zero-day campaign (Initial campaign prior to discovery): March 18-Dec. 29, 2022

- Second campaign (post-identification of CVE): March 15-29, 2023

- Third campaign: Aug. 30-Oct. 11, 2023

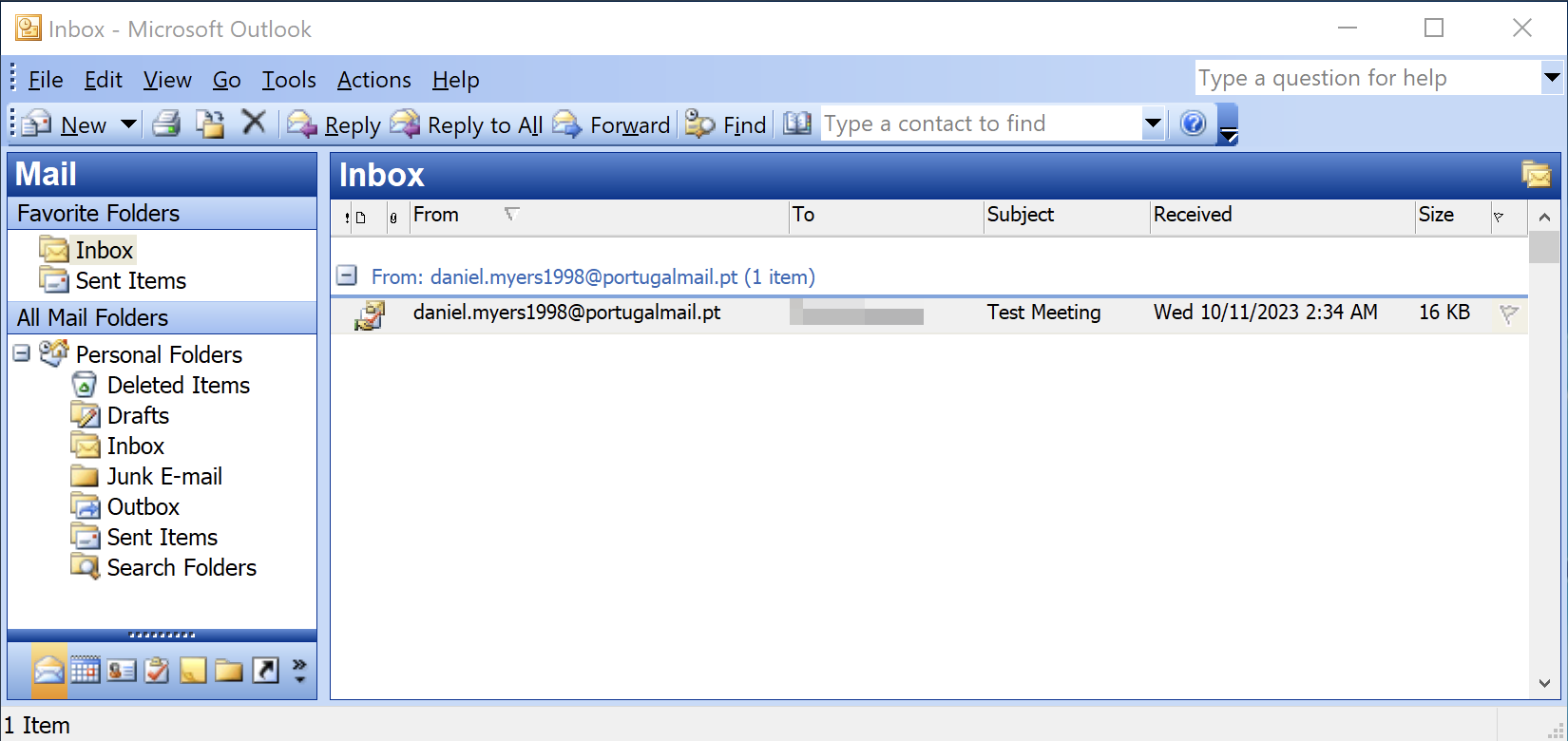

Figure 1 shows Fighting Ursa’s last observed attempt to use CVE-2023-23397 in a message sent to a Montenegrin Ministry of Defense account on Oct. 11, 2023. This message was sent from an account the actors had created on a public mail service (portugalmail[.]pt).

Successful exploitation of Microsoft Outlook using this vulnerability results in a relay attack using Windows (New Technology) NT LAN Manager (NTLM) as described in our threat brief for CVE-2023-23397.

NTLM is a challenge-response style authentication protocol that is prone to relay attacks, so Kerberos has been the default authentication protocol in Windows systems since Windows 2000. However, many Microsoft applications still use NTLM as a fallback protocol in cases where Kerberos is not feasible. Microsoft Outlook is one such application.

When a vulnerable or misconfigured Outlook application receives a specially crafted email exploiting CVE-2023-23397, Outlook sends an NTLM authentication message to an attacker-controlled remote file share. The NTLM authentication response is an NTLMv2 hash that Fighting Ursa uses to impersonate the victim, accessing and maneuvering within the victim's network. This is commonly known as an NTLM relay attack.

Unit 42 researchers attribute the activities within these campaigns to Fighting Ursa for two primary reasons:

- The targeted victims in these campaigns are all of apparent intelligence value to the Russian military.

- The campaigns all used co-opted Ubiquiti networking devices to harvest NTLM authentication messages from victim networks, which is consistent with previous Fighting Ursa campaigns.

Victimology: A Study in Russian Targeting Priorities

Delving into more than 50 observed samples in which Fighting Ursa targeted victims with CVE-2023-23397 provides unique and informative insights into Russian military priorities during a time of international conflict for them. Zero-day exploits by their nature are valuable commodities for APTs. Threat actors only use these exploits when the rewards associated with the access and intelligence gained outweigh the risk of public discovery of the exploit.

Using a zero-day exploit against a target indicates it is of significant value. It also suggests that existing access and intelligence for that target were insufficient at the time.

In the second and third campaigns, Fighting Ursa continued to use a publicly known exploit that was already attributed to them, without changing their techniques. This suggests that the access and intelligence generated by these operations outweighed the ramifications of public outing and discovery.

For these reasons, the organizations targeted in all three campaigns were most likely a higher than normal priority for Russian intelligence.

There are a few key takeaways when looking at the targets collectively, as shown in Figure 2:

- Other than Ukraine, all of the targeted European nations are current members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

- Attackers targeted at least one NATO Rapid Deployable Corps

- Outside of government organizations, attackers focused on targeting critical infrastructure-related organizations within the following sectors:

- Energy

- Transportation

- Telecommunications

- Information technology

- Military industrial base

Conclusion

It is rare to have such a detailed understanding of an APT’s targeting priorities, especially an APT like Fighting Ursa whose mission mandate is to conduct attacks on behalf of Russia’s military.

Governments and critical infrastructure providers across NATO and European nations are encouraged to take the following actions:

- Take note of these tactics

- Patch this vulnerability

- Configure endpoint protections to block these types of malicious campaigns

Protections and Mitigations

- Cortex XDR customers who have Advanced API Monitoring enabled receive protection from exploitation attempts of CVE-2023-23397 using XDR Anti-Exploit protection.

- The Next-Generation Firewall with the Advanced Threat Prevention security subscription can help block the attacks with best practices via the following Threat Prevention signature: 93635, 93705, 93584.

- Malicious URLs and IPs related to this activity are blocked by Advanced URL Filtering and DNS Security.

- The Advanced WildFire machine-learning models and analysis techniques have been reviewed and updated in light of the IoCs shared in this research.

If you think you might have been compromised or have an urgent matter, get in touch with the Unit 42 Incident Response team or call:

- North America Toll-Free: 866.486.4842 (866.4.UNIT42)

- EMEA: +31.20.299.3130

- APAC: +65.6983.8730

- Japan: +81.50.1790.0200

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance (CTA) members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Indicators of Compromise

- 5.199.162[.]132

- 101.255.119[.]42

- 181.209.99[.]204

- 213.32.252[.]221

- 168.205.200[.]55

- 69.162.253[.]21

- 185.132.17[.]160

- 69.51.2[.]106

- 113.160.234[.]229

- 24.142.165[.]2

- 85.195.206[.]7

- 42.98.5[.]225

- 61.14.68[.]33

- 50.173.136[.]70

Additional Resources

- Threat Brief - CVE-2023-23397 - Microsoft Outlook Privilege Escalation - Unit 42, Palo Alto Networks

- CVE-2023-23397 Playbook of the week - Palo Alto Networks

- Microsoft Outlook Elevation of Privilege Vulnerability: CVE-2023-23397 - Microsoft

- Microsoft Mitigates Outlook Elevation of Privilege Vulnerability - Microsoft

- Campagnes d’attaques du mode opératoire APT28 depuis 2021 - CERT-France

- U.S. Charges Russian GRU Officers with International Hacking and Related Influence and Disinformation Operations - United States Department of Justice

- Grand Jury Indicts 12 Russian Intelligence Officers for Hacking Offenses Related to the 2016 Election - United States Department of Justice

- Macron campaign was target of cyber attacks by spy-linked group - Reuters

- From Espionage to Cyber Propaganda: Pawn Storm's Activities over the Past Two Years - Trend Micro

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42