This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Overview

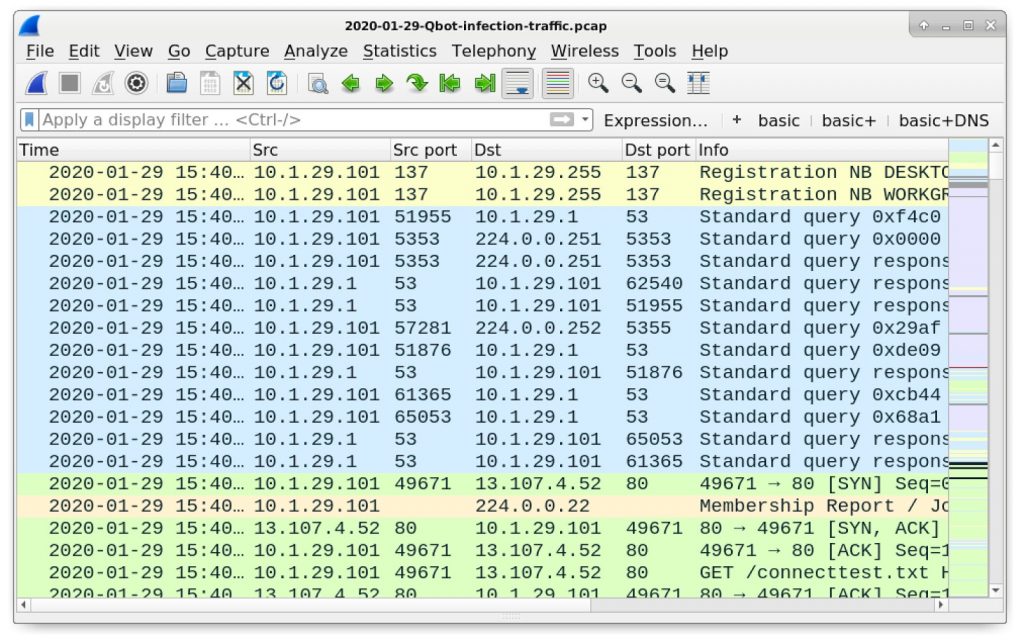

Qakbot is an information stealer also known as Qbot. This family of malware has been active for years, and Qakbot generates distinct traffic patterns. This Wireshark tutorial reviews a recent packet capture (pcap) from a Qakbot infection. Understanding these traffic patterns can be critical for security professionals when detecting and investigating Qakbot infections.

Note: This tutorial assumes you have a basic knowledge of network traffic and Wireshark. We use a customized column display shown in this tutorial. You should also have experience with Wireshark display filters as described in this additional tutorial.

Please also note that the pcap used for this tutorial contains malware. You should review this pcap in a non-Windows environment. If you are limited to a Windows computer, we suggest reviewing the pcap within a virtual machine (VM) running any of the popular recent Linux distros.

This tutorial will cover the following:

-

- Qakbot distribution methods

- Initial zip archive from link in an malspam

- Windows executable for Qakbot

- Post-infection HTTPS activity

- Other post-infection traffic

The pcap used for this tutorial is located here. Download the zip archive named 2020-01-29-Qbot-infection-traffic.pcap.zip and extract the pcap. Figure 1 shows our pcap open in Wireshark, ready to review.

Qakbot Distribution Methods

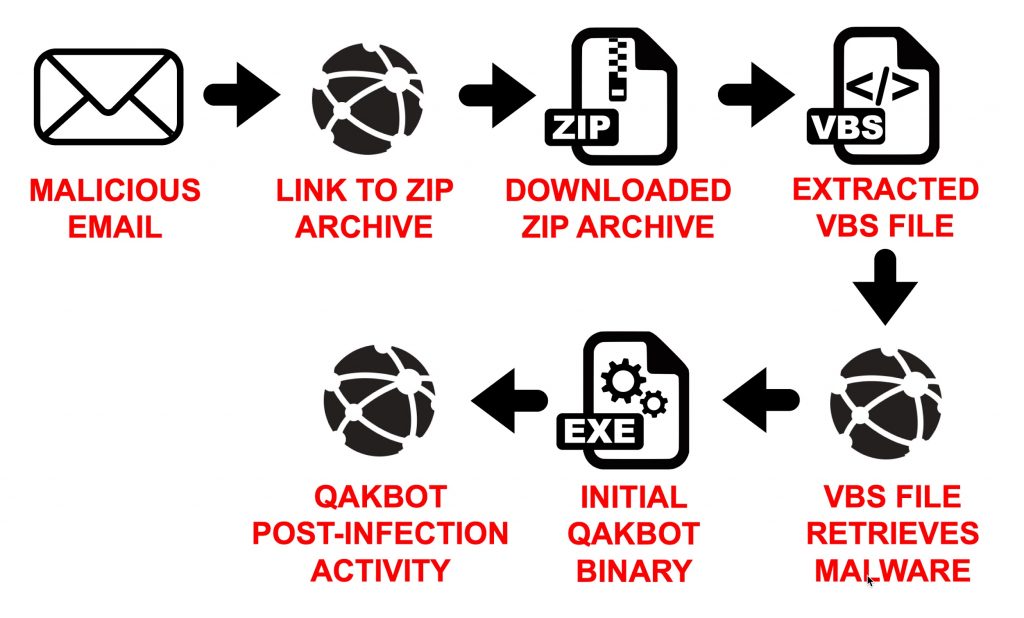

Qakbot is most often distributed through malicious spam (malspam), but it also has been distributed through exploit kits as recently as November 2019. In some cases, Qakbot is a follow-up infection caused by different malware like Emotet as reported in this example from March 2019.

Recent malspam-based distribution campaigns for Qakbot follow a chain of events shown in Figure 2.

Initial Zip Archive from Link in Malspam

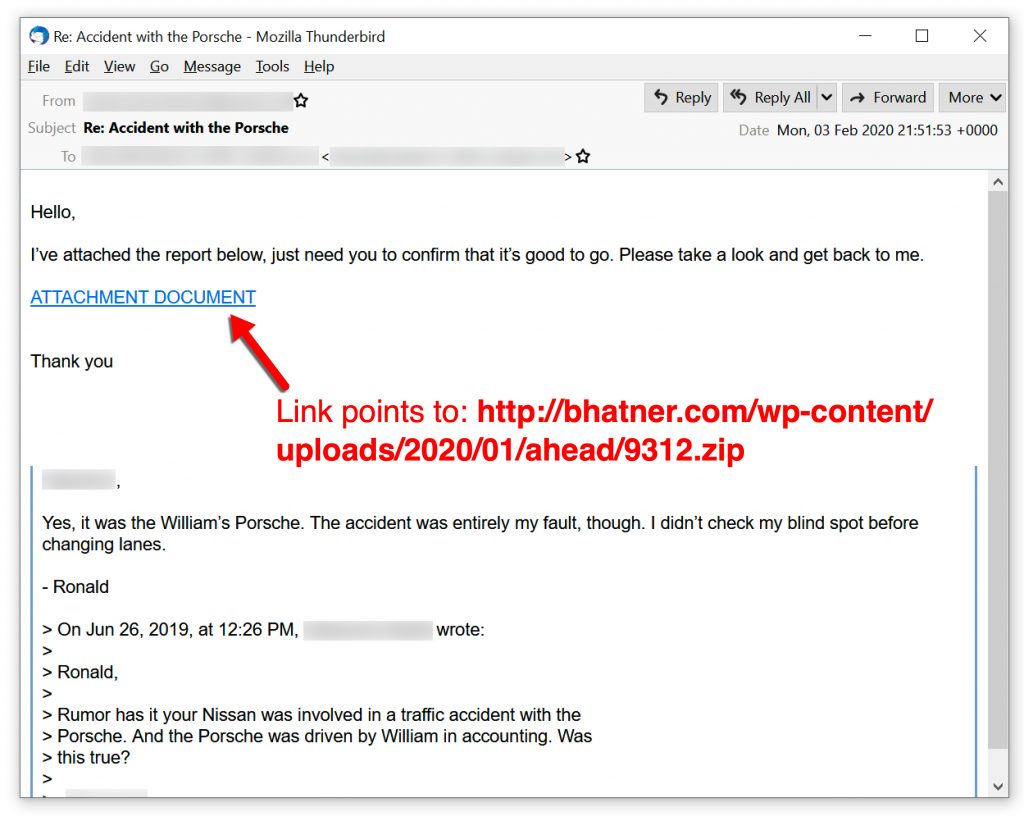

Recent malspam distributing Qakbot uses fake email chains that spoof legitimate email addresses. One such example is shown in Figure 3.

URLs from these emails end with a short series of numbers followed by .zip. See Table 1 for a few examples of URLs from Qakbot malspam recently reported on URLhaus and Twitter.

| First reported | URL for initial zip archive |

| 2019-12-27 | hxxps://prajoon.000webhostapp[.]com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/last/033/033.zip |

| 2019-12-27 | hxxps://psi-uae[.]com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/last/870853.zip |

| 2019-12-27 | hxxps://re365[.]com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/last/85944289/85944289.zip |

| 2019-12-27 | hxxps://liputanforex.web[.]id/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/last/794/794.zip |

| 2020-01-06 | hxxp://eps.icothanglong.edu[.]vn/forward/13078.zip |

| 2020-01-22 | hxxp://hitechrobo[.]com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/ahead/84296848/84296848.zip |

| 2020-01-22 | hxxp://faithoasis.000webhostapp.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/ahead/550889.zip |

| 2020-01-27 | hxxps://madisonclubbar[.]com/fast/invoice049740.zip |

| 2020-01-29 | hxxp://zhinengbao[.]wang/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/lane/00571.zip |

| 2020-01-29 | hxxp://bhatner[.]com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/ahead/9312.zip |

| 2020-02-03 | hxxp://santedeplus[.]info/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/ending/1582820/1582820.zip |

Table 1. URLs for the initial zip archive to kick off a Qakbot infection chain.

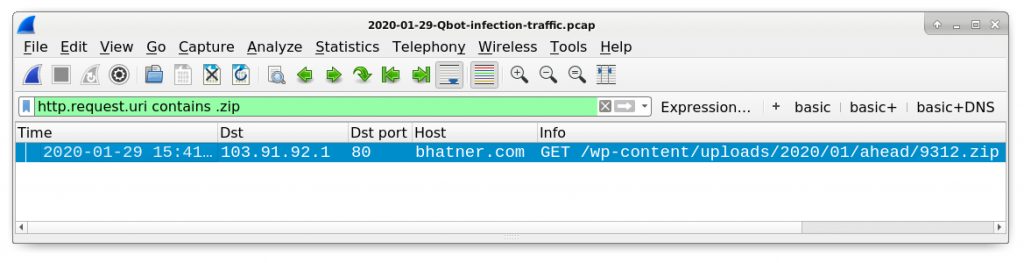

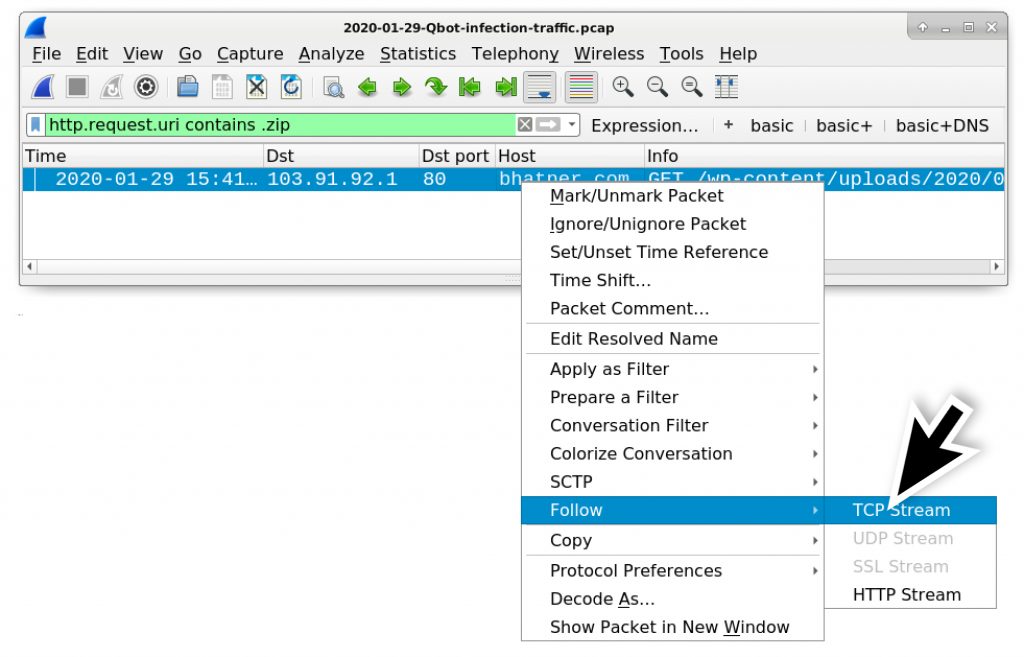

In our pcap, you can find the HTTP request for a zip archive using http.request.uri contains .zip in the Wireshark filter as shown in Figure 4.

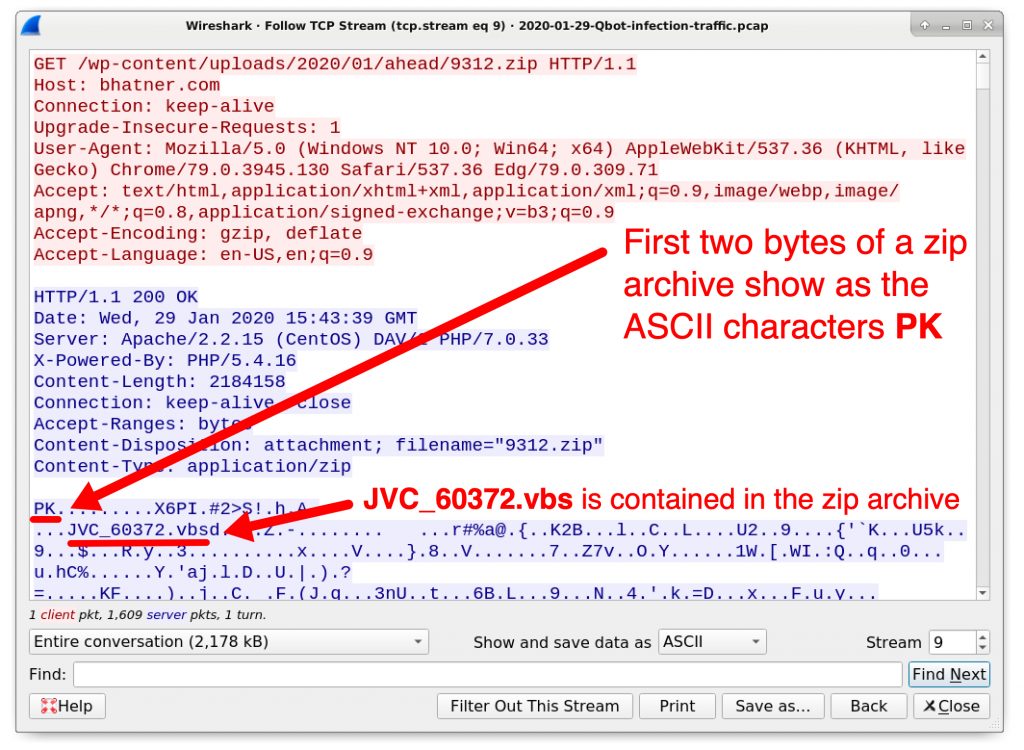

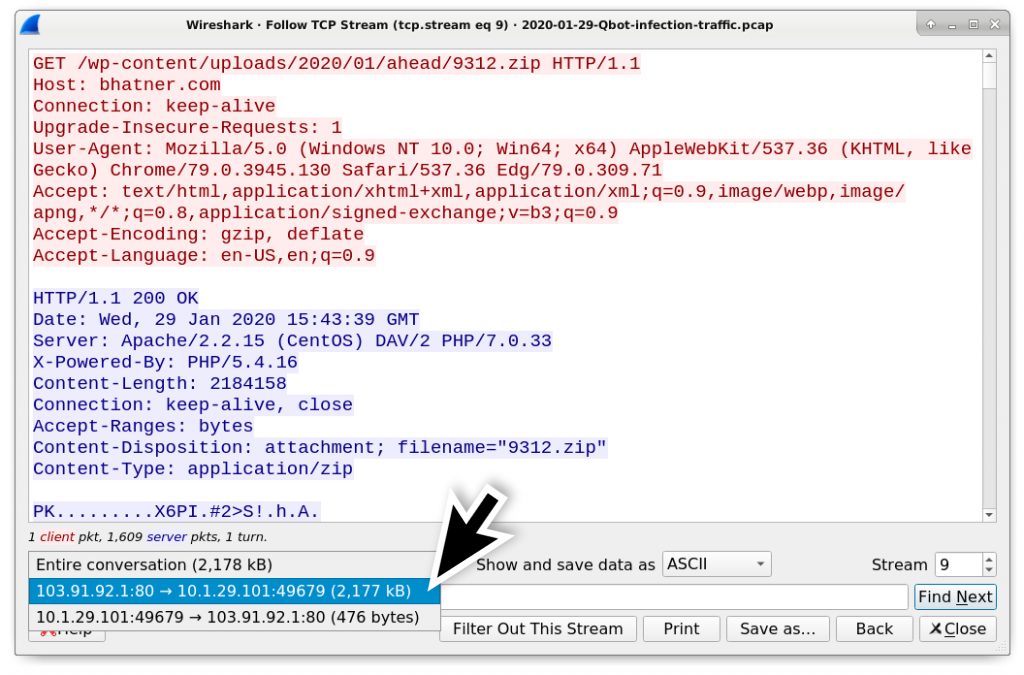

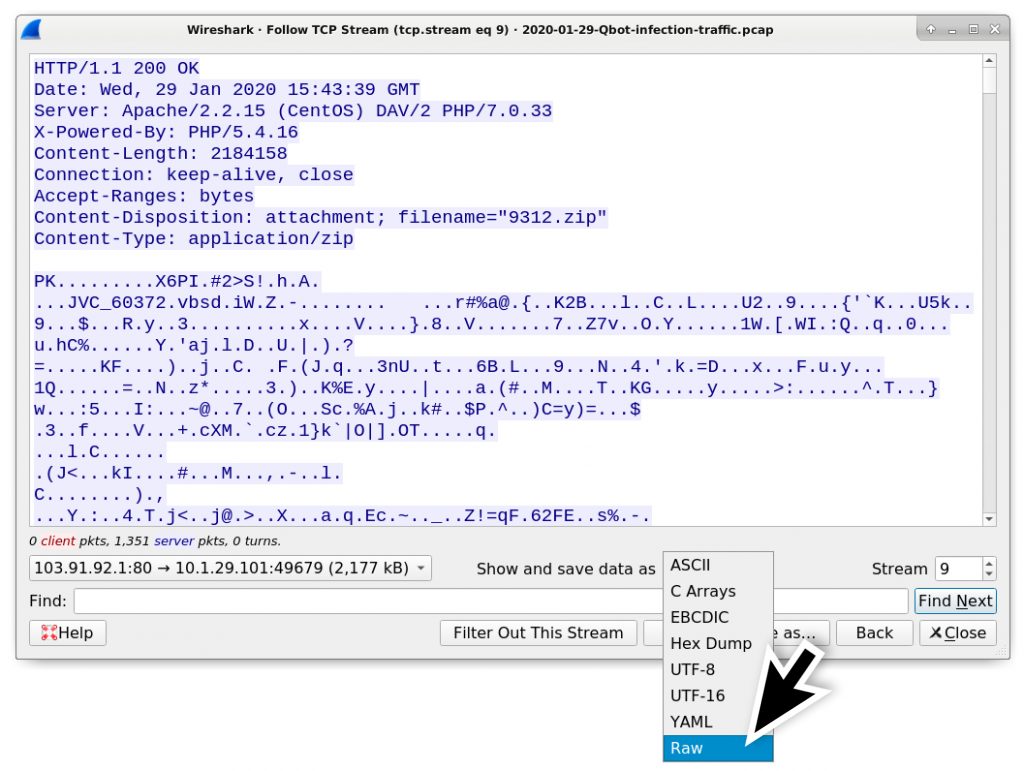

Follow the TCP stream to confirm this is a zip archive as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, then try to export the zip archive from the pcap as shown in Figure 7.

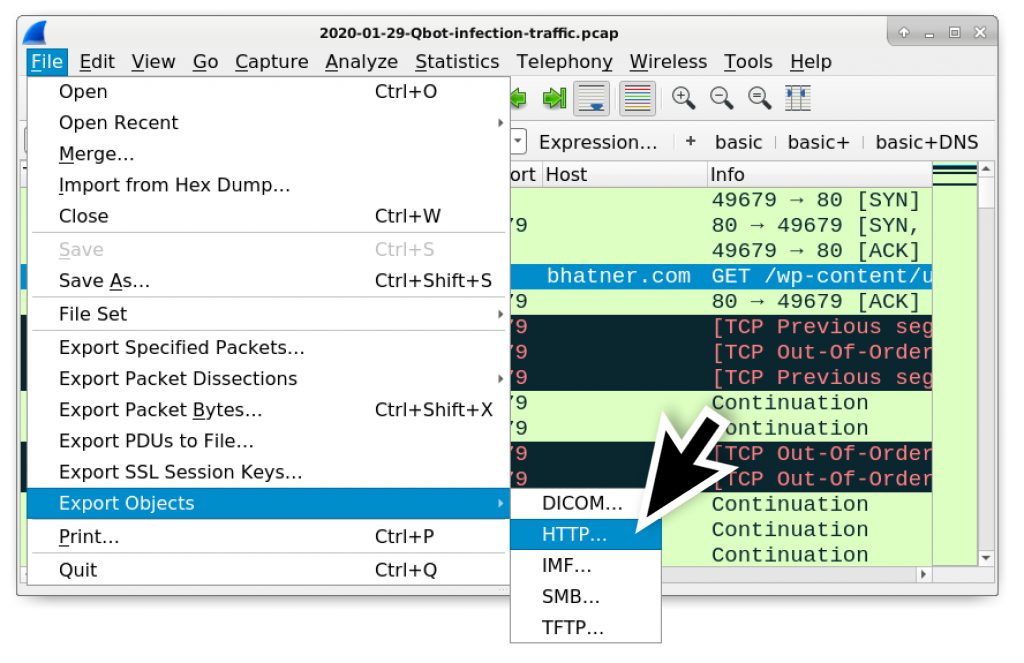

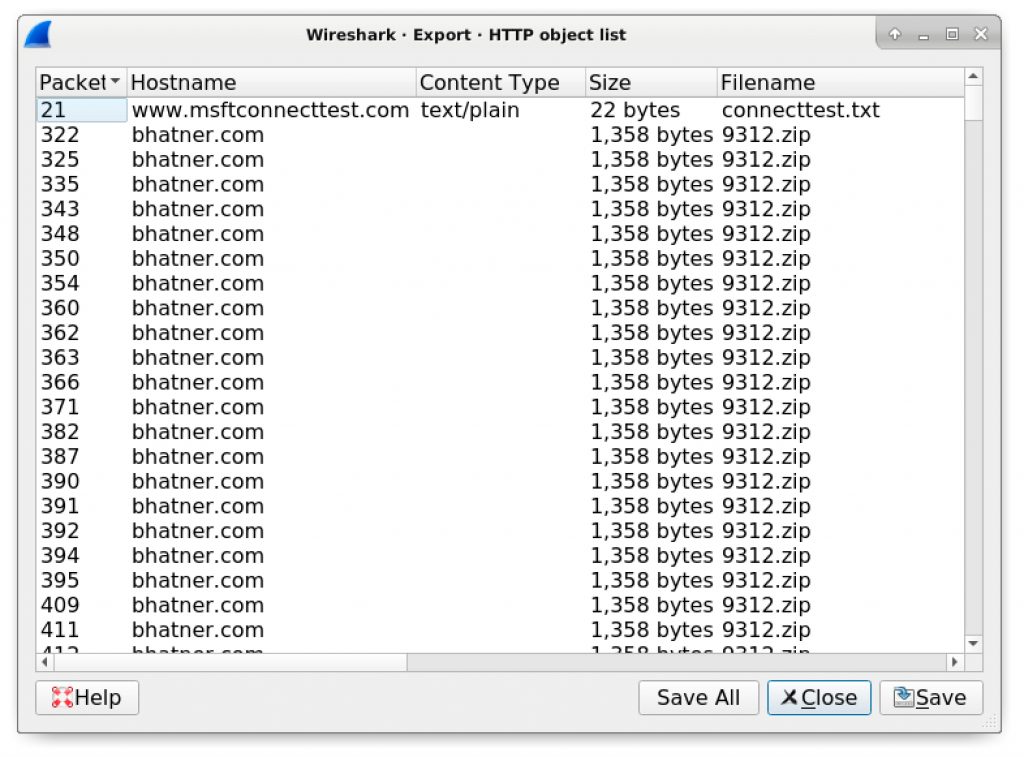

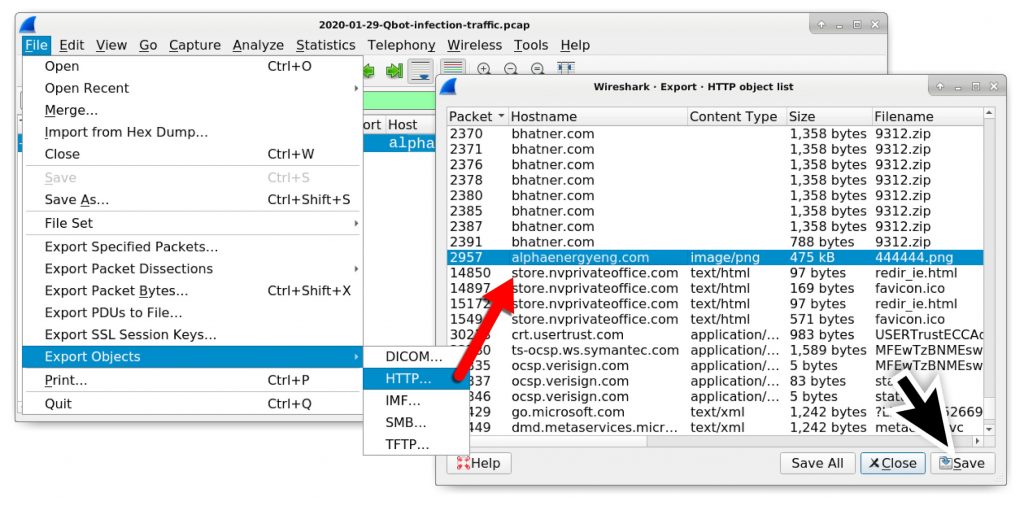

In most cases, the menu for File → Export Objects → HTTP should export a zip archive sent over HTTP. Unfortunately, as shown in Figure 8, we cannot export this file named 9312.zip because it is separated into hundreds of smaller parts within the export HTTP objects list.

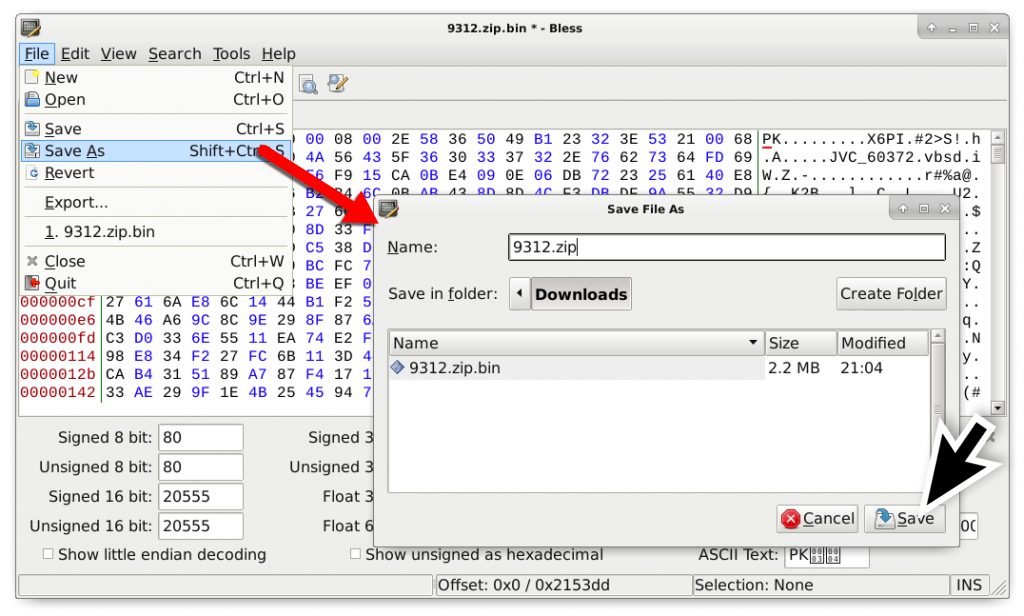

Fortunately, we can export data from a TCP stream window and edit the binary in a hex editor to remove any hxxP response headers. Use the following steps to extract the zip archive from this pcap:

-

- Follow TCP stream for the HTTP request for 9312.zip.

- Show only the response traffic in the TCP stream Window.

- Change “Show and save data as” from ASCII to Raw.

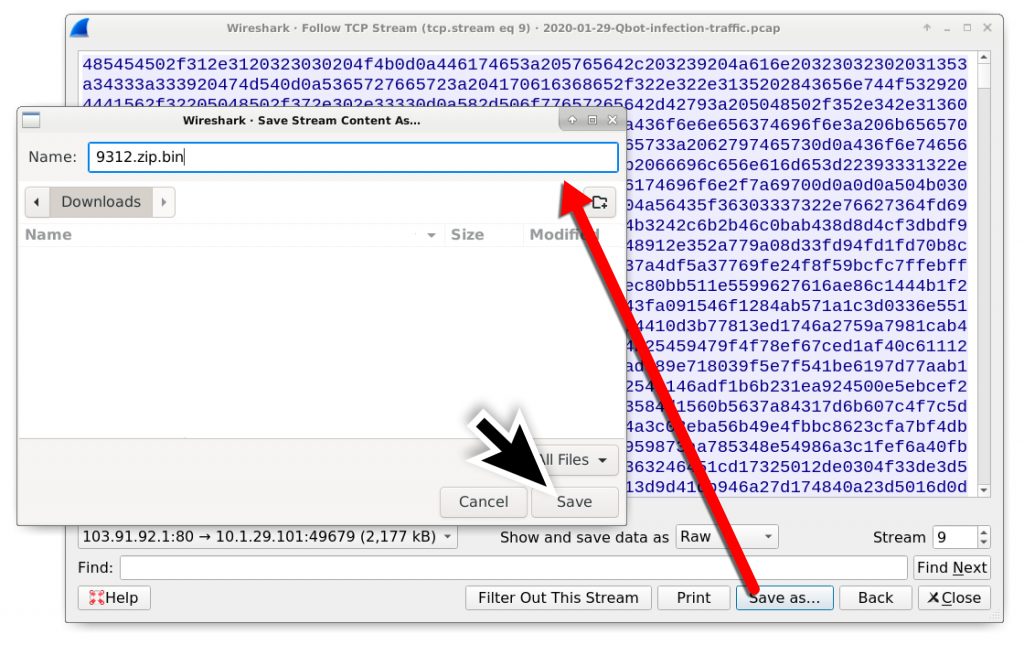

- Save the data as a binary (I chose to save it as: 9312.zip.bin)

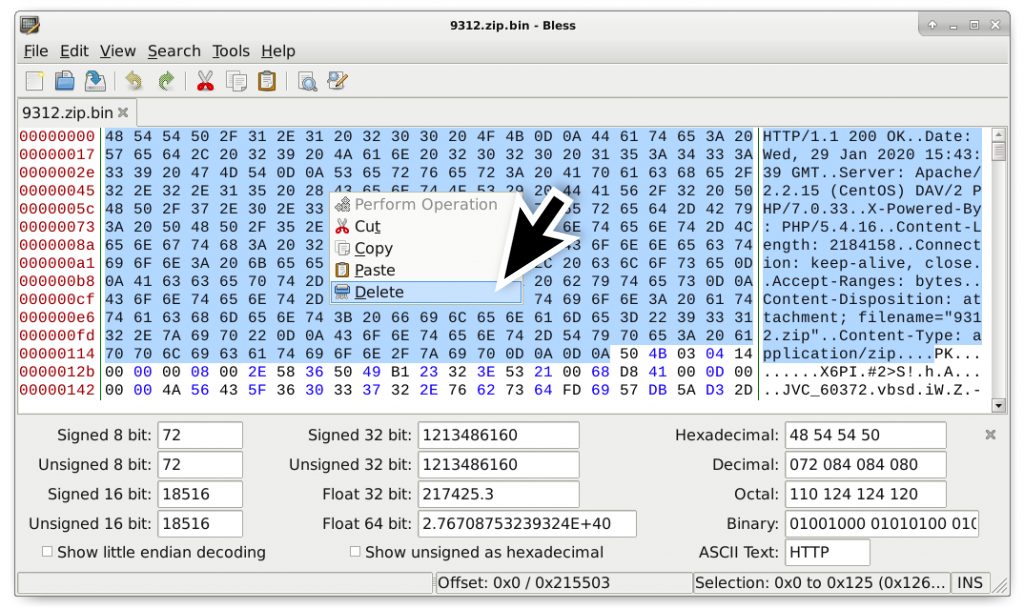

- Open the binary in a hex editor and remove the HTTP request headers before the first two bytes of the zip archive (which show as PK in ASCII).

- Save the file as a zip archive (I chose to save it as 9312.zip)

- Check the file to make sure it’s a zip archive.

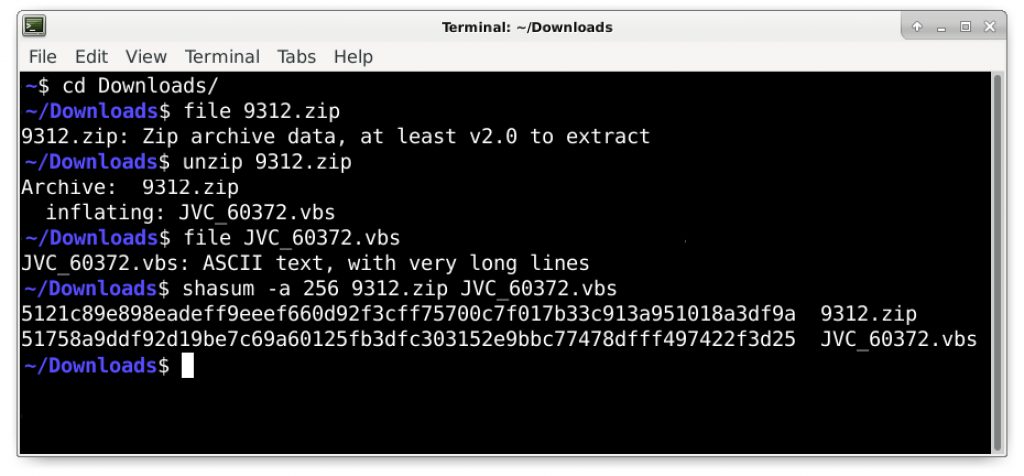

See Figures 9 through 14 for a visual guide of this process.

Figure 14 shows how to use a terminal window from a Debian-based Linux distro to check the files. From our pcap, the zip archive should be the same as this file submitted to VirusTotal. Our extracted VBS file should be the same as this file also submitted to VirusTotal.

A public sandbox analysis of our extracted VBS file indicates it generates the next Qakbot-related URL in our infection chain: a URL that returned a Windows executable for Qakbot.

Windows Executable for Qakbot

These extracted VBS files generate URLs that return Windows executables for Qakbot. Since December 2019, URLs for Qakbot executables have ended with 44444.png or 444444.png. See Table 2 for some recent examples of these Qakbot URLs we found using our AutoFocus Threat Intelligence service.

| First Seen | URL for Qakbot executable |

| 2019-12-27 | hxxp://centre-de-conduite-roannais[.]com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/last/444444.png |

| 2020-01-06 | hxxp://newsinside[.]info/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/forward/44444.png |

| 2020-01-15 | hxxp://iike.xolva[.]com/wp-content/themes/keenshot/fast/444444.png |

| 2020-01-17 | hxxp://deccolab[.]com/fast/444444.png |

| 2020-01-21 | hxxp://myrestaurant.coupoly[.]com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/along/444444.png |

| 2020-01-22 | hxxp://alphaenergyeng[.]com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/ahead/444444.png |

| 2020-01-23 | hxxp://claramohammedschoolstl[.]org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/upwards/444444.png |

| 2020-01-23 | hxxp://creationzerodechet[.]com/choice/444444.png |

| 2020-01-26 | hxxp://productsphotostudio[.]com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/lane/444444.png |

| 2020-01-27 | hxxp://sophistproduction[.]com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/choice/444444.png |

| 2020-01-30 | hxxp://uofnpress[.]ch/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/side/444444.png |

| 2020-02-03 | hxxp://csrkanjiza[.]rs/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/ending/444444.png |

Table 2. URLs for Qakbot executables.

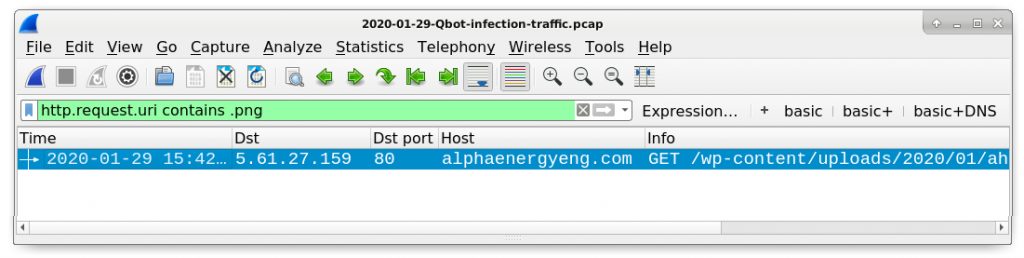

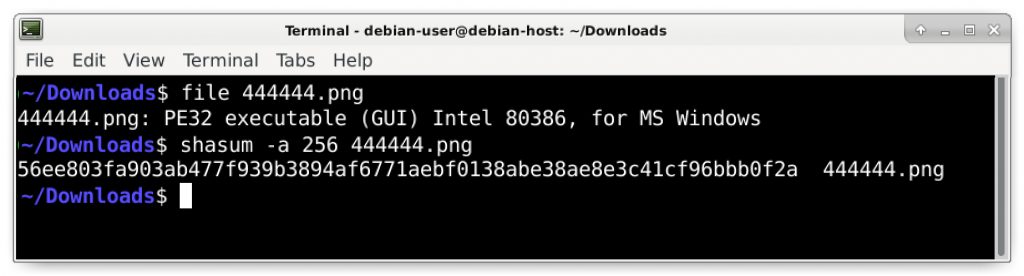

In our pcap, find the HTTP GET request for our Qakbot executable using hxxp.request.uri contains .png in the Wireshark filter as shown in Figure 15.

Export this object from the pcap using the File → Export Objects → HTTP menu path as shown in Figure 16 and check the results as shown in Figure 17.

From our pcap, the Qakbot executable should be this file submitted to VirusTotal. A public sandbox analysis of this file generated several Qakbot indicators (identified as Qbot).

Post-infection HTTPS Activity

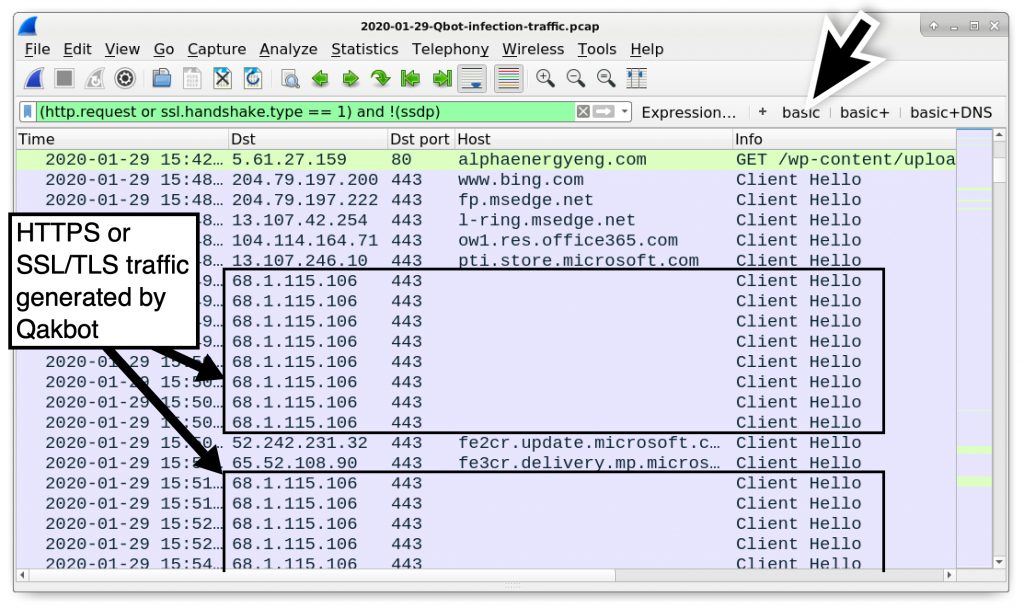

Use your basic filter (covered in this previous WIreshark tutorial) for a quick view of web traffic in our pcap. Scroll down to activity after the HTTP GET request to alphaenergyeng[.]com that returned our Qakbot executable. You should see several indicators of HTTPS or SSL/TLS traffic to 68.1.115[.]106 with no associated domain as noted in Figure 18.

This traffic has unusual certificate issuer data commonly noted during Qakbot infections. We reviewed unusual certificate issuer data in our previous WIreshark tutorial about Ursnif, so this should be easy to find.

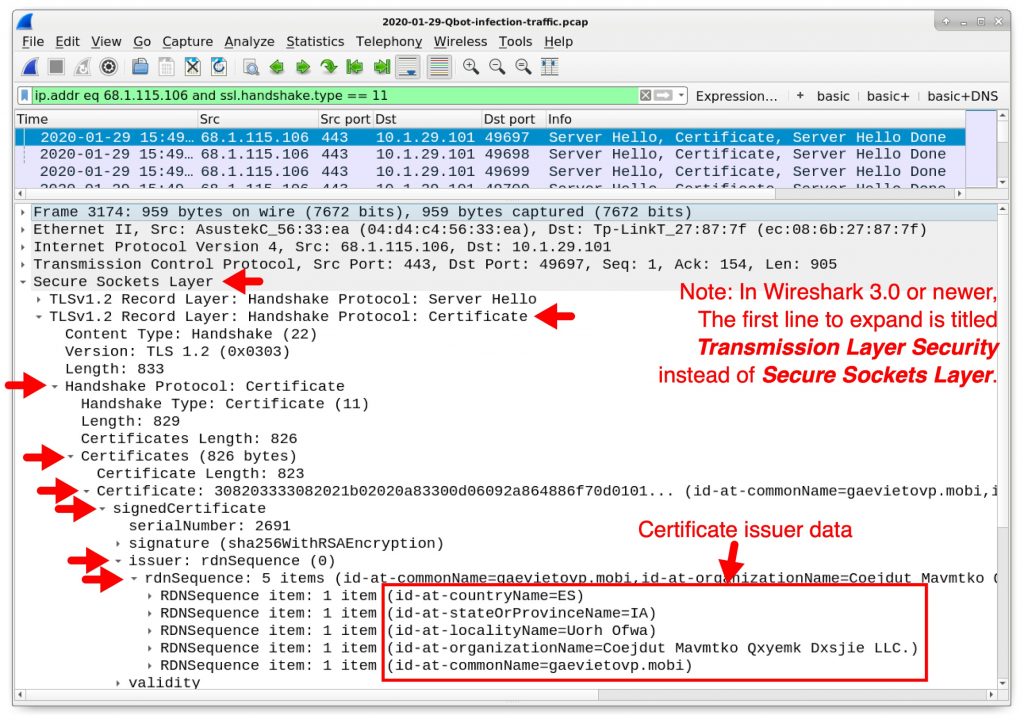

Let’s review our Qakbot certificate issuer data using the following Wireshark filter:

Ip.addr eq 68.1.115.186 and ssl.handshake.type eq 11

For Wireshark 3.0 or newer, use tls.handshake.type instead of ssl.handshake.type. Select the first frame in your results and expand the frame details window until you find the certificate issuer data as shown in Figure 19.

Patterns for the locality name, organization name, and common name are highly-unusual, not normally found in certificates from legitimate HTTPS, SSL, or TLS traffic. Our example of this issuer data is listed below:

-

- id-at-countryName=ES

- id-at-stateOrProvinceName=IA

- id-at-localityName=Uorh Ofwa

- id-at-organizationName=Coejdut Mavmtko Qxyemk Dxsjie LLC.

- id-at-commonName=gaevietovp.mobi

Other Post-infection Traffic

Our pcap contains other activity associated with a Qakbot infection. Each activity is not inherently malicious on its own, but taken together with our previous findings, we can assume a full Qakbot infection.

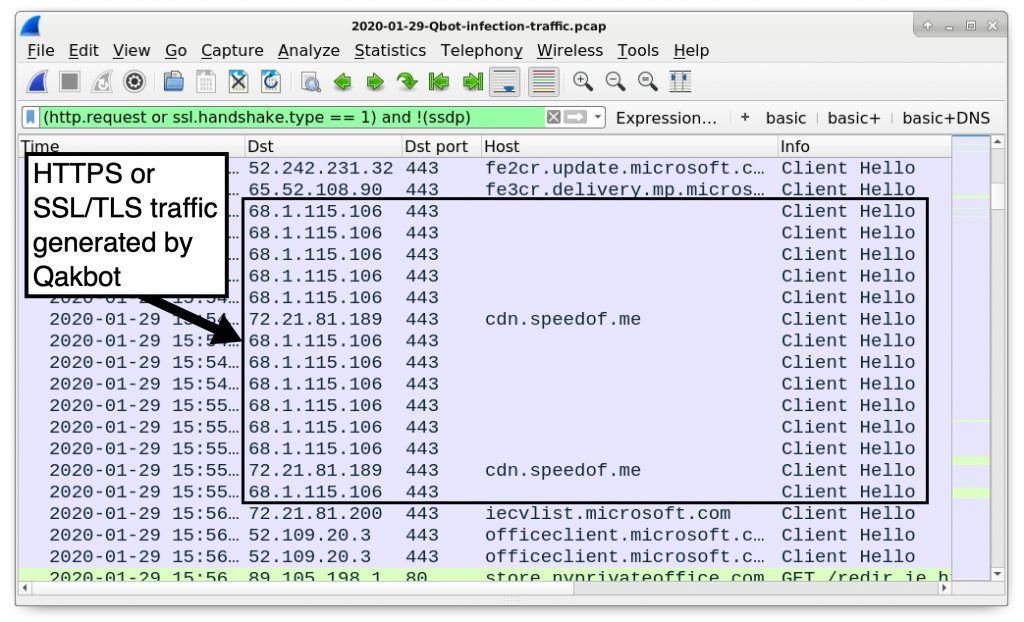

Another indicator of a Qakbot infection is HTTPS traffic to cdn.speedof[.]me. The domain speedof[.]me is used by a legitimate Internet speed test service. Although this is not malicious traffic, we frequently see traffic to cdn.speedof[.]me during Qakbot infections. Figure 20 shows this activity from our pcap.

- hxxp://store.nvprivateoffice[.]com/redir_chrome.html

- hxxp://store.nvprivateoffice[.]com/redir_ff.html

- hxxp://store.nvprivateoffice[.]com/redir_ie.html

The domain nvprivateoffice[.]com has been registered through GoDaddy since 2012, and store.nvprivateoffice[.]com shows a default web page for nginx on a Fedora server.

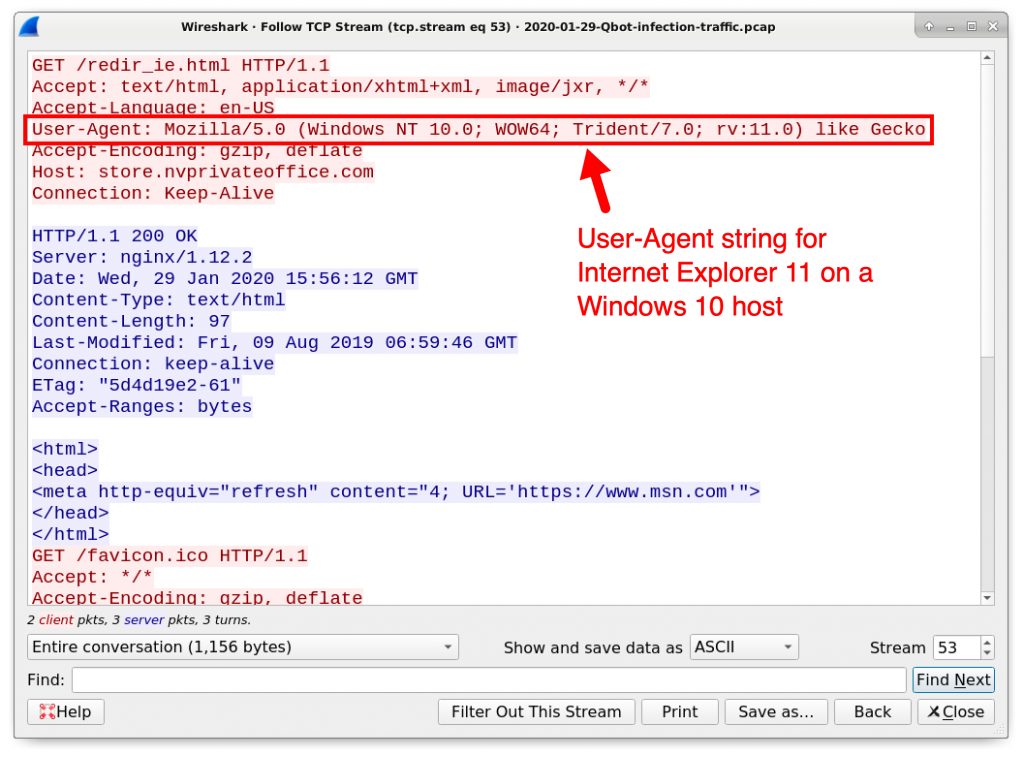

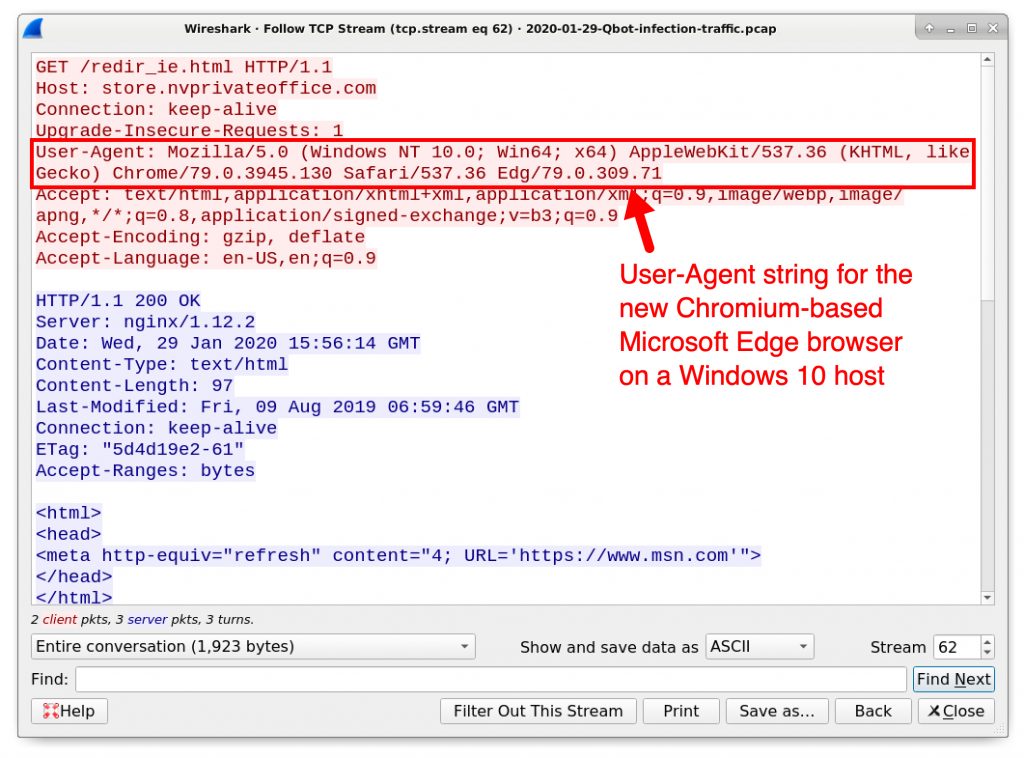

Our pcap for this tutorial is from a Qakbot infection on a Windows 10 host without Chrome or Firefox installed. Our pcap only shows web traffic for Internet Explorer and the new Chromium-based Microsoft Edge. Both times, the URL generated by Qakbot was hxxp://store.nvprivateoffice[.]com/redir_ie.html.

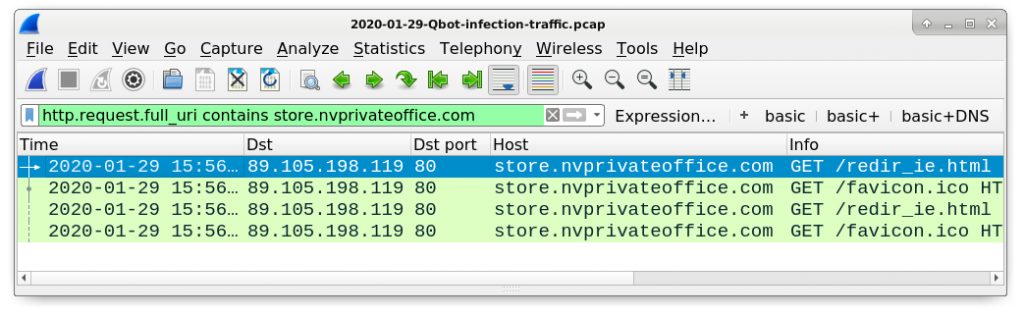

To find this traffic, use the following Wireshark filter as shown in Figure 21:

http.request.full_uri contains store.nvprivateoffice

Follow the TCP stream for each of the two HTTP GET requests ending in redir_ie.html. The first request has a User-Agent in the HTTP headers for Internet Explorer as shown in Figure 22. The second request for the same URL has a User-Agent in the HTTP headers for the new Chromium-based Microsoft Edge as noted in Figure 23.

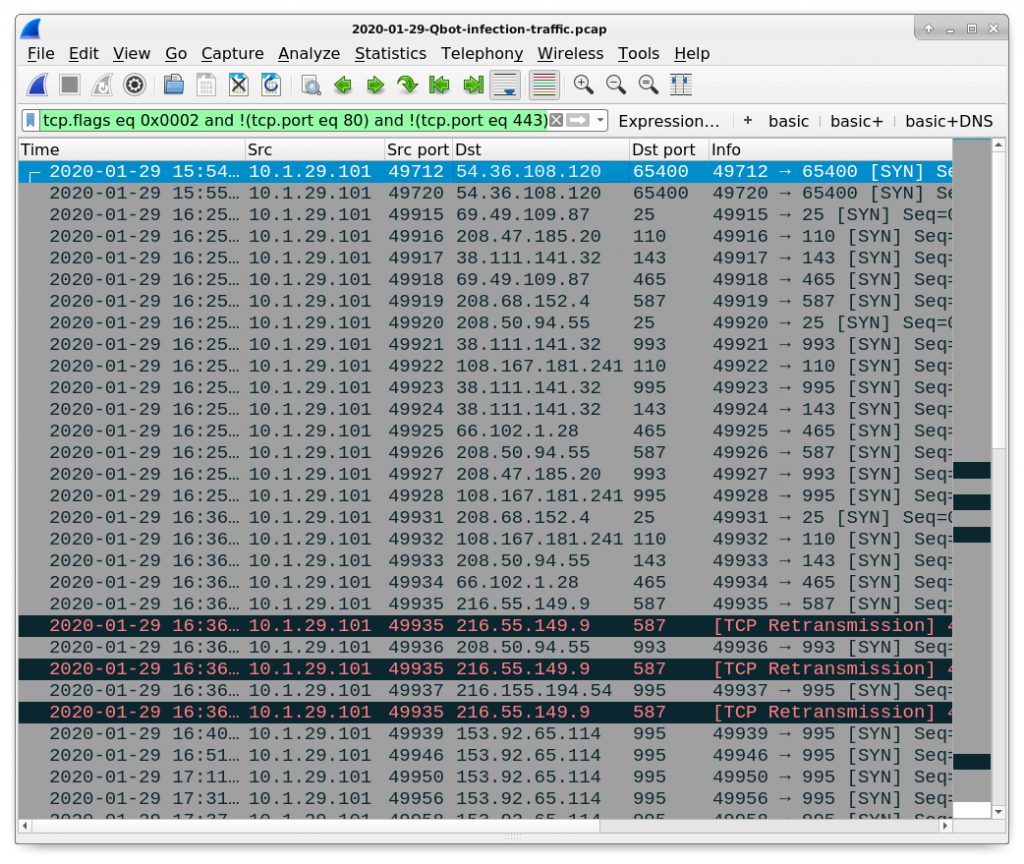

tcp.flags eq 0x0002 and !(tcp.port eq 80) and !(tcp.port eq 443)

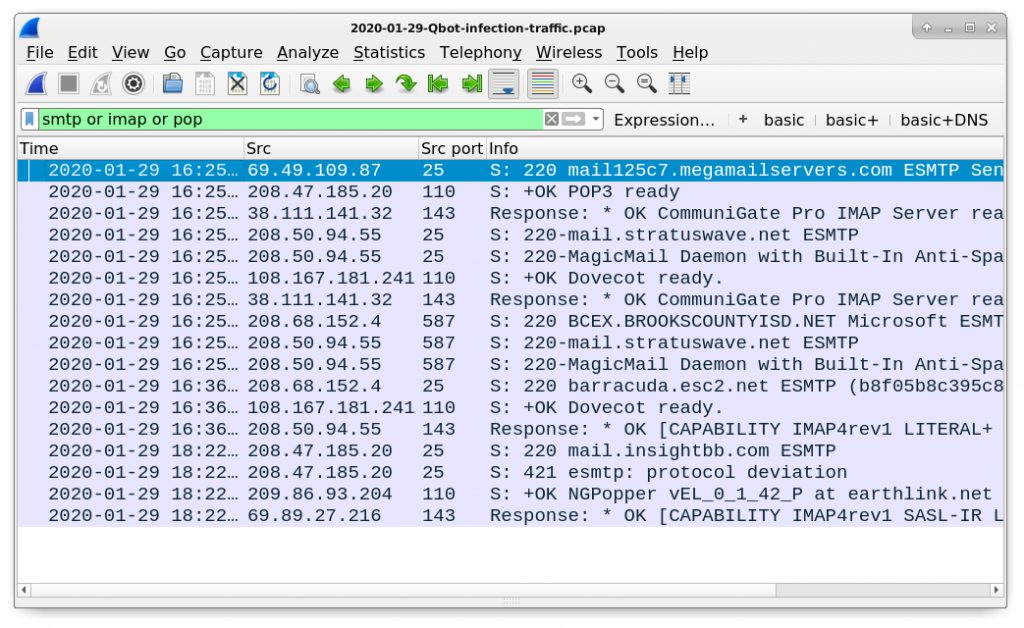

Figure 25 shows TCP connections and attempted TCP connections to various ports like 25, 110,143, 465, 587, 993, and 995 commonly used by different email protocols. The first two lines in the results show traffic to TCP port 65400, but reviewing the associated TCP streams indicates this also email-related traffic.

Use the following Wireshark filter to get a better idea of email-related traffic from the infected host as shown in Figure 26:

smtp or imap or pop

Follow some of the TCP streams to get a better idea for this type of email traffic. We do not normally see such unencrypted email traffic originating from a Windows client to public IP addresses. Along with other indicators, this smtp or imap or pop filter may reveal Qakbot activity.

Conclusion

This tutorial provided tips for examining Windows infections with Qakbot malware. More pcaps with examples of Qakbot activity can be found at malware-traffic-analysis.net.

For more help with Wireshark, see our previous tutorials:

- Customizing Wireshark – Changing Your Column Display

- Using Wireshark – Display Filter Expressions

- Using Wireshark: Identifying Hosts and Users

- Using Wireshark: Exporting Objects from a Pcap

- Wireshark Tutorial: Examining Trickbot Infections

- Wireshark Tutorial: Examining Ursnif Infections

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42