Unit 42 researchers recently observed an unusually clever spambot’s attempts to increase delivery efficacy by abusing reputation blacklist service APIs. Rather than sending spam as soon as the host is infected, the bot checks common blacklists to confirm its e-mails will actually be delivered, and if not, shuts itself down. This spambot, commonly downloaded by the Andromeda malware, has been observed delivering pharmaceutical industry spam as well as further propagating the main Andromeda bot. Microsoft refers to this family of malware as Sarvdap, however it must be noted that the detection appears somewhat generic. We have not identified any other public names for this malware, so rather than introduce a new name to the industry we’ll refer to this family as Sarvdap.

The Malware

The malware uses hardcoded addresses for function names and strings but to properly execute, it relies on the base of the module to be at 0x20010000. If this is not the case, the malware will not be able to resolve function addresses or string references and will not function. Upon initial execution the malware drops a copy of itself into the %windir% folder, executes a new svchost.exe process, initializes itself by allocating memory, injects the main bot code into this process, checks for a debugger to evade analysts, and creates the mutex "Start_Main_JSM_complete".

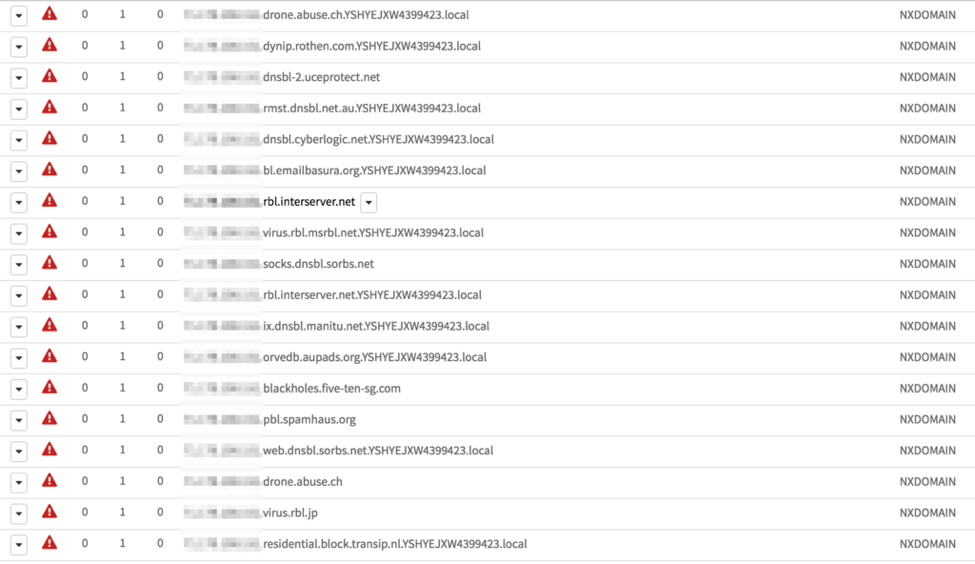

Once this stage is finished the malware checks the connection by attempting to connect to www.microsoft.com. If this connectivity check passes, the malware proceeds to enumerate multiple blacklist feeds to determine the host IP's reputation status. Provided the malware determines it is not located on a blacklisted host, which would cause it to terminate, it then beacons to its hardcoded command and control server over TCP port 2352. Details of this exchange are located in the Appendix below.

Provided the C2 is online and the host passes RBL checks, the malware expects to download and read a configuration file and use this information to populate fields in numerous data structures. The server which served configurations was offline at the time of analysis and we were not able to pull the actual configuration file that was being served/expected. In order to maintain accuracy, no suppositions will be made as to what the configuration contained; this is because the most interesting capability of this malware is still present within the original code.

Figure1. DNS lookups performed by the malware shown in AutoFocus.

Additional host enumeration commands were identified during memory analysis of this sample on a live host:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

ON LINE:ts=%s:jid=%s:sid=%s:ver=%s:login=%s:pass=%s:port=%u:ports=%u:ip=%s:isp=%s:country= %s:ccode=%s:region=%s:city=%s:time_zone=%s:ct=%s:sc=%s:uptime=%u:osid=%s:inuse=%s:bac k=%s:rbl=%s:END ON LINE:ts=%s:jid=%s:sid=%s:ver=%s:login=%s:pass=%s:port=%u:ports=%u:ip=%s:isp=%s:ct=%s:sc= %s:uptime=%u:osid=%s:inuse=%s:back=%s:rbl=%s:END |

RBL Check Functionality

This malware is interesting because it contains a hardcoded list of commonly known blacklist servers. These servers are used as a means to check the infected host/zombie to determine if this infection is live and not on any of the provided blacklists. The blacklists checked are from all around the world and rather comprehensive, indicating the author was trying to get global coverage rather than that of a specific region.

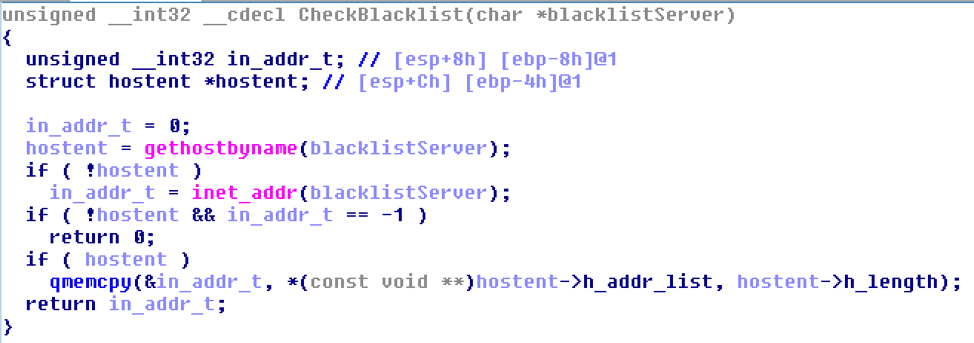

The semantics of this check are similar to code snippets found online. The pseudocode of this function can be seen below:

Figure 2. Pseudocode representing DNS RBL lookups and decision tree.

The GetHostByName() function is called for each blacklist URL to see if the IP is blacklisted, if the IP address is in the DNS blacklist then it will return the hostname (IP+BlacklistAddress) instead of an IP address.

If the IP is not on the blacklist, then the malware sends S5R: %u: OK (%u argument is going to be the current blacklist server that is being checked) to the server. If the malware determines it is on a blacklisted host, the process will terminate.

Conclusion

Phishing emails remain a highly prevalent threat for enterprise, government and home users. For-hire, large-scale spam focused botnets continue to churn out hundreds of thousands of messages a day from compromised hosts. Sarvdap is particularly interesting not due to its scale, but rather due to its attempts to increase overall spam delivery by abusing reputation blacklists.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected from this family through Threat Prevention and WildFire, and AutoFocus customers can track this malware via the Sarvdap tag.

Appendix: Example Phone Home Exchange

The following is an example of the exchange between the Sarvdap infected host. Note that the host identifier (srv_00000000000000000000000000000000) changes depending on the infected host.

Initial Beacon:

|

1 |

<id>srv_ 00000000000000000000000000000000 id> |

C2 Response:

|

1 2 |

OK 217.160.6.96....<msg from='' to='srv_00000000000000000000000000000000 '>GEOINFO:http://whoer.net</msg> |

Host Reply:

|

1 2 3 4 |

<msg from='srv_00000000000000000000000000000000 ' to='MASTER001'>ON LINE:ts=$TS:jid=$JID:sid=00000000000000000000000000000000 ver=70:login=xxx:pass=xxx:port=10:ports=10:ip= 217.160.6.96:isp=:ct=:sc=466.8 kbps:uptime=99:osid=Windows XP Service Pack 3:inuse=false:back=back:rbl=7/82:END</msg> |

Note that the “rbl” field in the Host Reply message appears to report total number of blacklist hits.

IOCs

Sample used for analysis:

117172d6c59957be3c7a3c60cc0978ae430e3c15cb2e863cc5227b5fd0058ded

C2 Servers

dop.premiocastelloacaja[.]com

k1.clanupstairs[.]com

mall.giorgioinvernizzi[.]com

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42